A Study of Antibiotic Tolerance to Levofloxacin and Rifampin in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Prosthetic Joint Infections: Clinical Relevance and Treatment Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

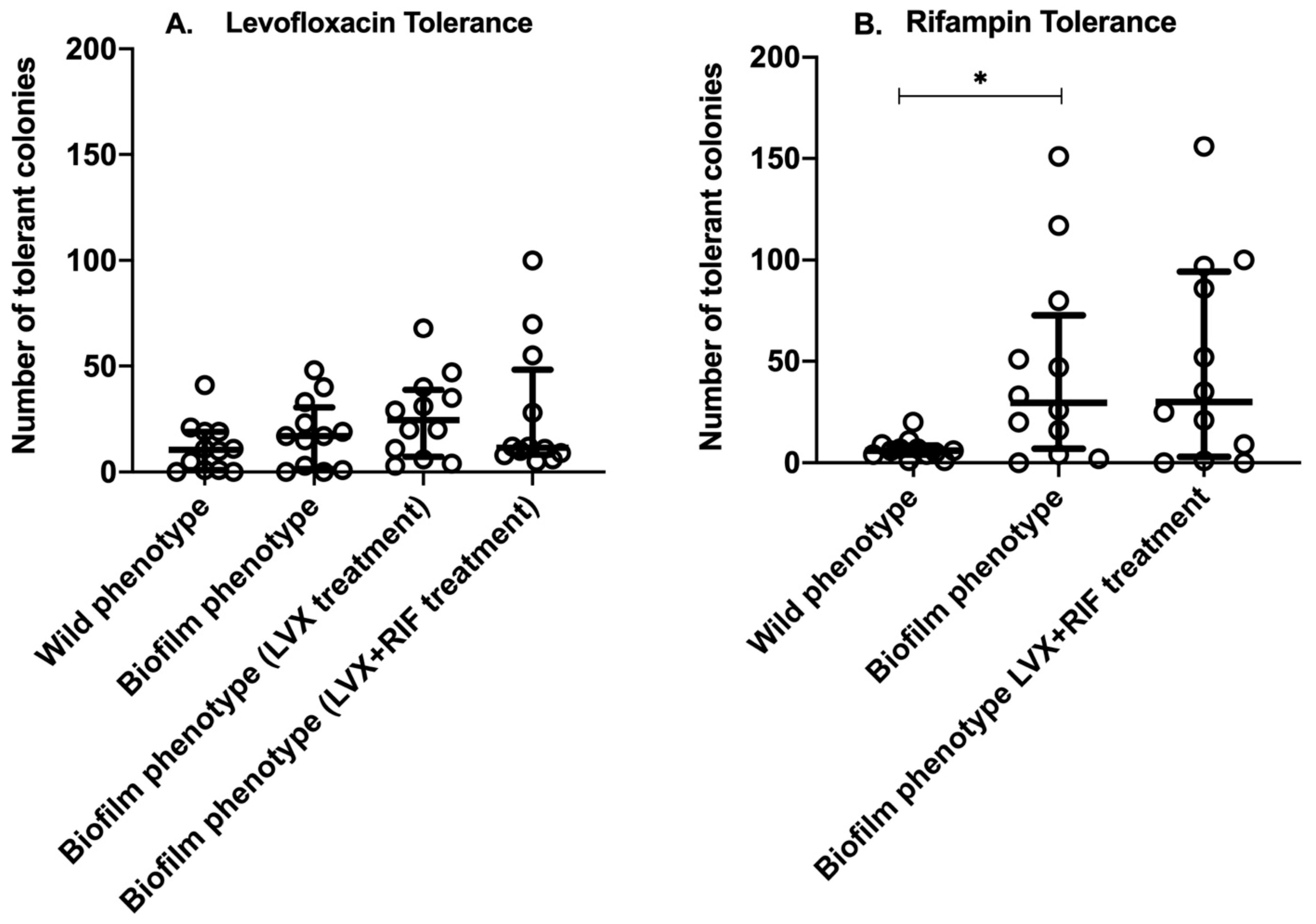

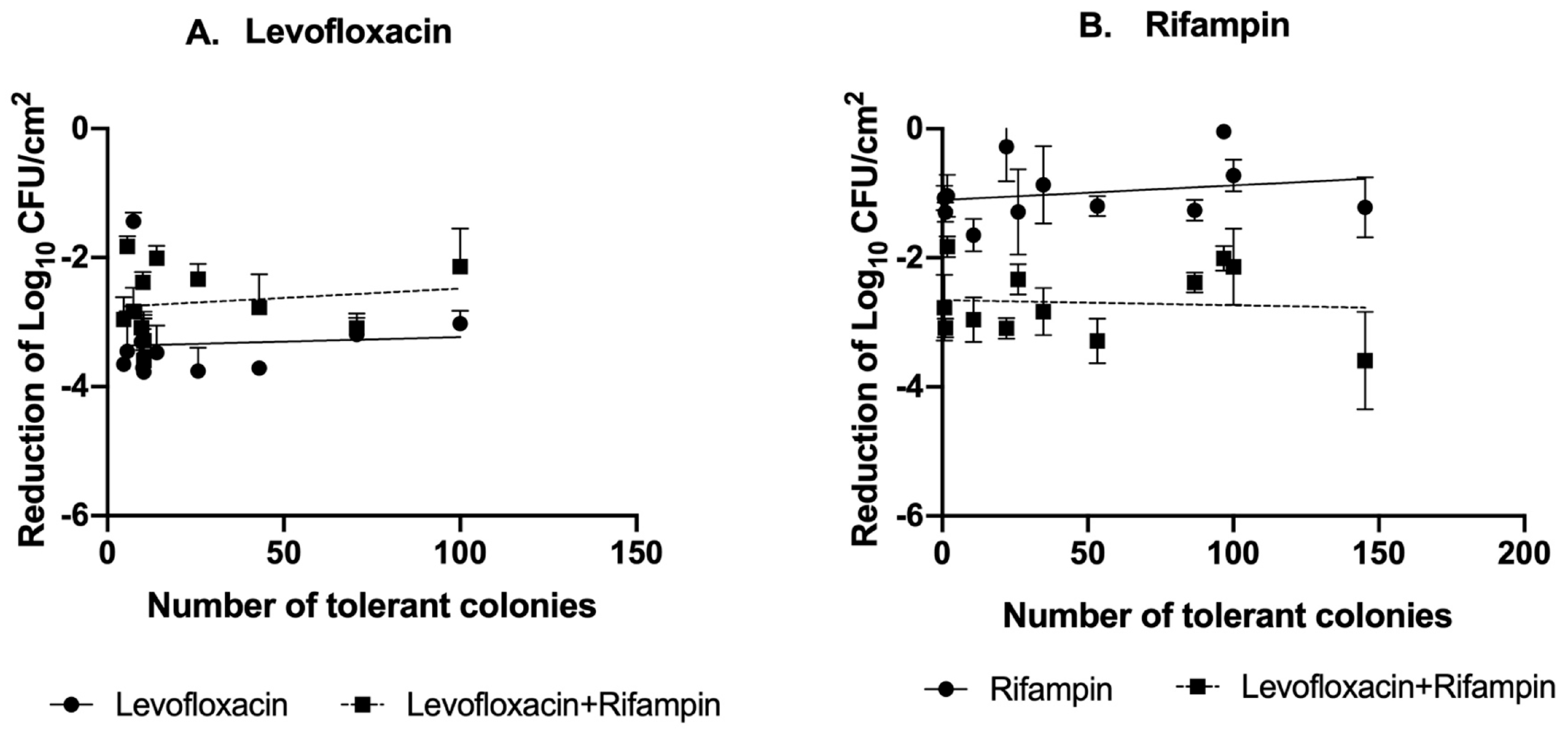

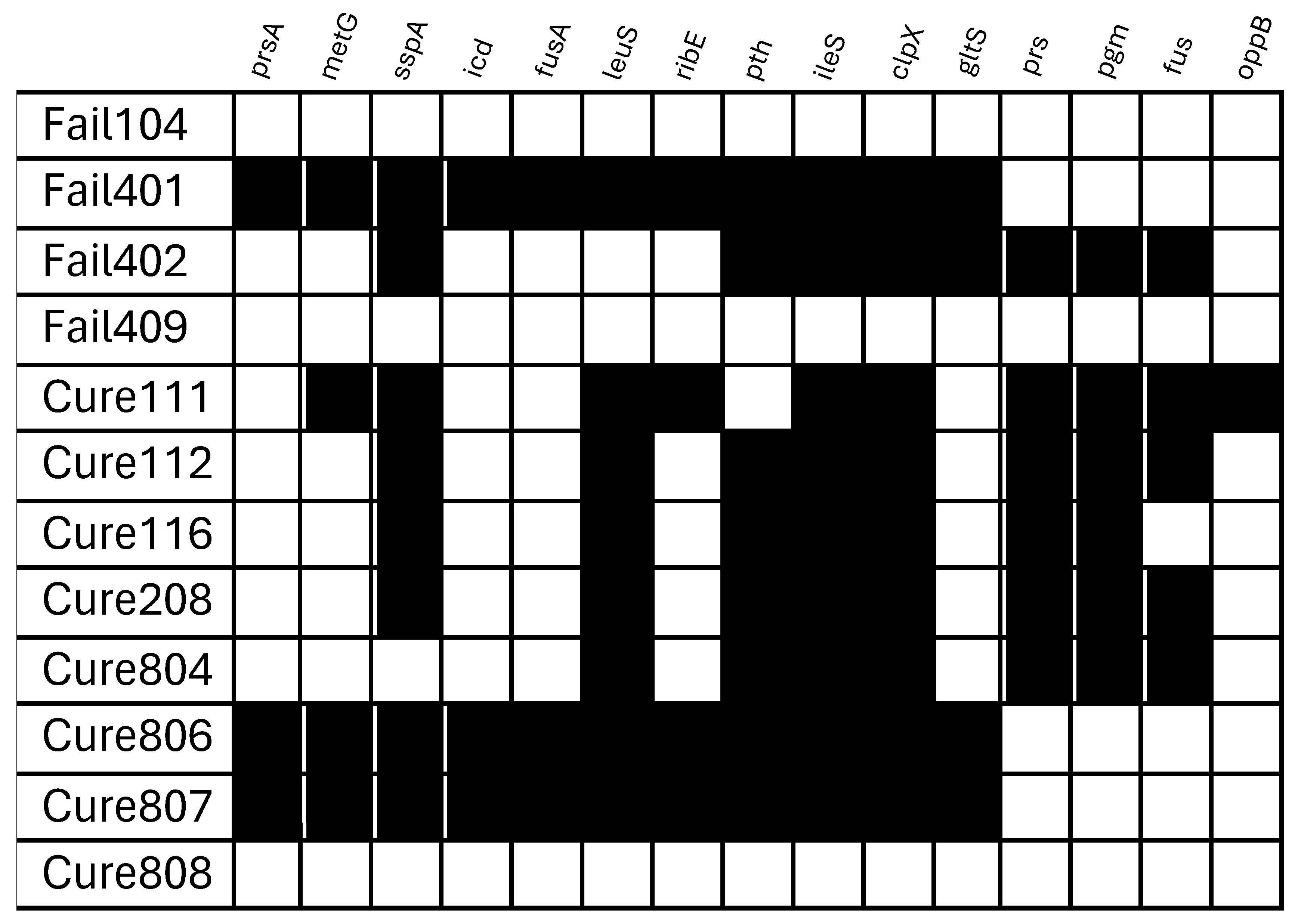

2.2. Tolerance of S. aureus Isolates to Levofloxacin and Rifampin Under Different Stress Conditions

2.3. Tolerance According to Clinical Prognosis

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

4.2. Antimicrobials and Susceptibility Testing

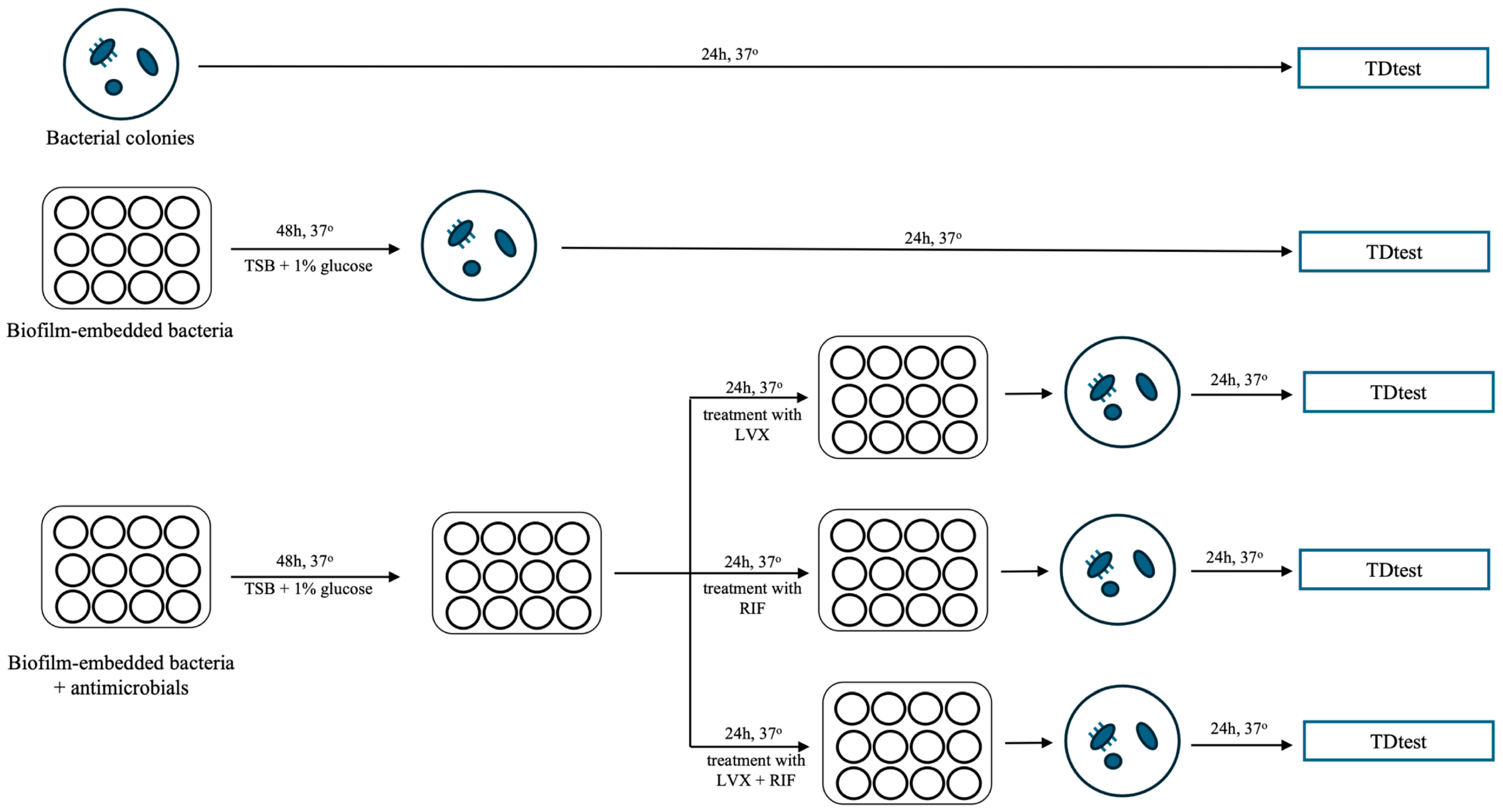

4.3. Tolerance Detection Test (TDtest)

4.4. Static In Vitro Biofilm Model

4.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Gene Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brauner, A.; Fridman, O.; Gefen, O.; Balaban, N.Q. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.S. Antimicrobial Tolerance in Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulin, C.; Leimer, N.; Huemer, M.; Ackermann, M.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Prolonged bacterial lag time results in small colony variants that represent a sub-population of persisters. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gefen, O.; Ronin, I.; Bar-Meir, M.; Balaban, N.Q. Effect of tolerance on the evolution of antibiotic resistance under drug combinations. Science 2020, 367, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W.; Trampuz, A.; Ochsner, P.E. Prosthetic-joint infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito, N.; Franco, M.; Ribera, A.; Soriano, A.; Rodriguez-Pardo, D.; Sorlí, L.; Fresco, G.; Fernández-Sampedro, M.; Dolores del Toro, M.; Guío, L.; et al. Time trends in the aetiology of prosthetic joint infections: A multicentre cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 732.e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza, J.; Cobo, J.; Baraia-Etxaburu, J.; Benito, N.; Bori, G.; Cabo, J.; Corona, P.; Esteban, J.; Horcajada, J.P.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; et al. Executive summary of the management of prosthetic joint infections. Clinical guidelines by the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC). Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2017, 35, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmon, D.R.; Berbari, E.F.; Berendt, A.R.; Lew, D.; Zimmerli, W.; Steckelberg, J.M.; Rao, N.; Hanssen, A.; Wilson, W.R.; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, e1–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, W.; Sendi, P. Role of Rifampin against Staphylococcal Biofilm Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01746-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J.; Williamson, K.S.; Folsom, J.P.; Boegli, L.; James, G.A. Contribution of stress responses to antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3838–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Lam, H. Evolution of Bacterial Tolerance Under Antibiotic Treatment and Its Implications on the Development of Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 617412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Gallego, I.; Meléndez-Carmona, M.Á.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Garrido-Allepuz, C.; Chaves, F.; Sebastián, V.; Viedma, E. Microbiological and Molecular Features Associated with Persistent and Relapsing Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Joint Infection. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Carmona, M.Á.; Mancheño-Losa, M.; Ruiz-Sorribas, A.; Muñoz-Gallego, I.; Viedma, E.; Chaves, F.; Van Bambeke, F.; Lora-Tamayo, J. Strain-to-strain variability among Staphylococcus aureus causing prosthetic joint infection drives heterogeneity in response to levofloxacin and rifampicin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 3265–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Tamayo, J.; Meléndez-Carmona, M.Á. The clinical meaning of biofilm formation ability: The importance of context. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, O.; Chekol, B.; Strahilevitz, J.; Balaban, N.Q. TDtest: Easy detection of bacterial tolerance and persistence in clinical isolates by a modified disk-diffusion assay. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotková, H.; Cabrnochová, M.; Lichá, I.; Tkadlec, J.; Fila, L.; Bartošová, J.; Melter, O. Evaluation of TD test for analysis of persistence or tolerance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 167, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Mohler, J.; Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uruén, C.; Chopo-Escuin, G.; Tommassen, J.; Mainar-Jaime, R.C.; Arenas, J. Biofilms as promoters of bacterial antibiotic resistance and tolerance. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tande, A.J.; Patel, R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 302–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, O.; Pachón, M.E.; Euba, G.; Verdaguer, R.; Tubau, F.; Cabellos, C.; Cabo, J.; Gudiol, F.; Ariza, J. Antagonistic effect of rifampin on the efficacy of high-dose levofloxacin in staphylococcal experimental foreign-body infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3681–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Gallego, I.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Pérez-Montarelo, D.; Brañas, P.; Viedma, E.; Chaves, F. Influence of molecular characteristics in the prognosis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections: Beyond the species and the antibiogram. Infection 2017, 45, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Tang, X.; Dong, W.; Sun, N.; Yuan, W. A Review of Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Its Regulation Mechanism. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Lam, H. Novel Daptomycin Tolerance and Resistance Mutations in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Adaptive Laboratory Evolution. mSphere 2021, 6, e00692-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Gallego, I.; Viedma, E.; Esteban, J.; Mancheño-Losa, M.; García-Cañete, J.; Blanco-García, A.; Rico, A.; García-Perea, A.; Garbajosa, P.R.; Escudero-Sánchez, R.; et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections: Insight on pathogenesis and prognosis of a multicentre prospective cohort. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky, A.L. M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 8, 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 14.0, 2024. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Ruiz-Sorribas, A.; Poilvache, H.; Kamarudin, N.H.N.; Braem, A.; Van Bambeke, F. In vitro polymicrobial inter-kingdom three-species biofilm model: Influence of hyphae on biofilm formation and bacterial physiology. Biofouling 2021, 37, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieme, L.; Hartung, A.; Tramm, K.; Graf, J.; Spott, R.; Makarewicz, O.; Pletz, M.W. Adaptation of the Start-Growth-Time Method for High-Throughput Biofilm Quantification. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 631248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landersdorfer, C.B.; Bulitta, J.B.; Kinzig, M.; Holzgrabe, U.; Sörgel, F. Penetration of antibacterials into bone: Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and bioanalytical considerations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain Code a | LVX MIC (mg/L) | Levofloxacin Tolerance (Absolute Number of Tolerant Colonies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Biofilm Bacteria | Biofilm Bacteria | Biofilm-LVX Treatment | Biofilm-LVX + RIF Treatment | ||

| Fail104 | 0.25 | 23 ± 4.4 | 26 ± 6.1 | 26.7 ± 6.8 | 10.3 ± 4.2 |

| Fail401 | 0.125 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 2.3 |

| Fail402 | 0.125 | 18.3 ± 3.1 | 16.3 ± 1.2 | 46 ± 5.6 | 70.7 ± 6.0 |

| Fail409 | 0.25 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 66 ± 9.2 | 14 ± 5.3 |

| Cure111 | 0.25 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 3.2 |

| Cure112 | 0.19 | 19.3 ± 2.5 | 20 ± 2.6 | 18.7 ± 4.2 | 5.7 ± 2.1 |

| Cure116 | 0.19 | 39.3 ± 3.8 | 46 ± 4.4 | 13 ± 4.4 | 10 ± 4.0 |

| Cure208 | 0.19 | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 30.7 ± 4.9 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 100 |

| Cure804 | 0.125 | 0 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 32.7 ± 4.9 | 43 ± 22.5 |

| Cure806 | 0.125 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 16.7 ± 4.7 | 35.7 ± 9.9 | 7.3 ± 1.2 |

| Cure807 | 0.125 | 10.7 ± 2.1 | 16.7 ± 1.5 | 20.3 ± 1.5 | 10.3 ± 2.9 |

| Cure808 | 0.19 | 8.3 ± 7.4 | 39.3 ± 1.2 | 39.7 ± 1.5 | 25.7 ± 9.7 |

| Mean ± SD b | . | 11.3 ± 11.9 | 18.0 ± 15.5 | 26.01 ± 19.0 | 26.0 ± 30.4 |

| CVg c | . | 104.80% | 86.00% | 73.20% | 117.00% |

| Strain Code a | RIF MIC (mg/L) | Rifampin Tolerance (Absolute Number of Tolerant Colonies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Biofilm Bacteria | Biofilm Bacteria | Biofilm-RIF Treatment b | Biofilm-LVX + RIF Treatment | ||

| Fail104 | 0.012 | 7.3 ± 4.9 | 80 ± 5.0 | - | 145.3 ± 22.0 |

| Fail401 | 0.008 | 29 ± 15.6 | 113.3 ± 11.9 | - | 10.7 ± 3.8 |

| Fail402 | 0.008 | 5.7 ± 4.2 | 54.7 ± 16.9 | - | 22 ± 9.5 |

| Fail409 | 0.016 | 6.7 ± 5.0 | 144.3 ± 25.7 | - | 96.7 ± 6.5 |

| Cure111 | 0.008 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 25.3 ± 5.0 | - | 1 ± 1.0 |

| Cure112 | 0.012 | 5 ± 4.3 | 19 ± 2.6 | - | 1.7 ± 2.9 |

| Cure116 | 0.012 | 3.3 ± 2.1 | 3.7 ± 2.5 | - | 86.7 ± 5.0 |

| Cure208 | 0.006 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 30.7 ± 4.9 | - | 100 |

| Cure804 | 0.008 | 1.7 ± 2.1 | 0 | - | 0.7 ± 1.2 |

| Cure806 | 0.012 | 10.7 ± 1.5 | 54.7 ± 17.8 | - | 34.7 ± 1.5 |

| Cure807 | 0.016 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 17.3 ± 5.1 | - | 53.3 ± 5.1 |

| Cure808 | 0.012 | 14 ± 8.9 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | - | 26 ± 9.5 |

| Mean ± SD c | . | 7.93 ± 7.53 | 45.4 ± 46.25 | . | 48.2 ± 48.0 |

| CVg d | . | 95.00% | 101.80% | . | 99.60% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meléndez-Carmona, M.Á.; Muñoz-Gallego, I.; Mancheño-Losa, M.; Lora-Tamayo, J. A Study of Antibiotic Tolerance to Levofloxacin and Rifampin in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Prosthetic Joint Infections: Clinical Relevance and Treatment Challenges. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010010

Meléndez-Carmona MÁ, Muñoz-Gallego I, Mancheño-Losa M, Lora-Tamayo J. A Study of Antibiotic Tolerance to Levofloxacin and Rifampin in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Prosthetic Joint Infections: Clinical Relevance and Treatment Challenges. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeléndez-Carmona, María Ángeles, Irene Muñoz-Gallego, Mikel Mancheño-Losa, and Jaime Lora-Tamayo. 2026. "A Study of Antibiotic Tolerance to Levofloxacin and Rifampin in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Prosthetic Joint Infections: Clinical Relevance and Treatment Challenges" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010010

APA StyleMeléndez-Carmona, M. Á., Muñoz-Gallego, I., Mancheño-Losa, M., & Lora-Tamayo, J. (2026). A Study of Antibiotic Tolerance to Levofloxacin and Rifampin in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Prosthetic Joint Infections: Clinical Relevance and Treatment Challenges. Antibiotics, 15(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010010