Abstract

Background/Objectives: Acne vulgaris is a prevalent dermatological condition, yet clear, region-specific management guidelines, particularly for India’s diverse population, remain limited. Effective acne management extends beyond pharmacologic therapy, emphasizing proper skincare, patient education, and adherence strategies. This consensus aims to provide tailored, evidence-based recommendations for optimizing acne treatment in the Indian context. Methods: A panel of 14 dermatology experts with ≥15 years of experience reviewed literature, real-world clinical practices, and patient-centric factors relevant to acne management in India. Using a modified Delphi process with two virtual voting rounds, 61 statements across seven clinical domains were evaluated. Consensus was defined as ≥75% agreement. Results: Topical retinoids remain the first-line therapy, with combination regimens (benzoyl peroxide or topical antibiotics) preferred to enhance efficacy and minimize antibiotic resistance. Hormonal therapies, including combined oral contraceptives and spironolactone, are recommended for females with resistant acne. Guidance includes individualized treatment plans, baseline investigations, and selection of appropriate topical and systemic agents. Special considerations for pregnancy and lactation prioritize maternal and fetal safety. Conclusions: This expert consensus provides practical, evidence-based recommendations for acne management in India, integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. The tailored guidance supports individualized care, antibiotic stewardship, and improved treatment adherence, aiming to enhance patient outcomes nationwide.

1. Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic condition of the pilosebaceous unit [1]. It is multifactorial in origin, most commonly presenting during adolescence but often persisting into adulthood [2]. The global prevalence is estimated at 20%, while in Asia, it is slightly lower at 19.4% [3]. In India, acne predominantly affects individuals aged 18–25 years, with a significantly higher prevalence in females (81.7%) [2,4].

Diagnosis is based on identifying characteristic lesions, which include noninflammatory comedones (open or closed) and inflammatory lesions such as papules, pustules, and nodules [1]. Adolescent acne is more straightforward to diagnose, whereas adult-onset acne may require endocrine evaluation [5]. Common sequelae include facial scarring, postinflammatory erythema (PIE), and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), which can often be more distressing than the acne itself [2,4,6]. Severe acne and scarring are frequently associated with a positive family history [7]. An observational study conducted in South India reported scarring in 34% of cases and pigmentation in 40%, with a family history of acne present in 33% of the individuals [8]. The risk of scarring is further increased in patients with skin-picking behaviors or excoriation disorder [9]. Delayed treatment initiation is another key contributor to scarring [10]. As a result, patients with active or unresolved acne frequently experience psychological distress, including depression and negative body image [11].

Standardized acne severity assessment is critical for guiding treatment and evaluating outcomes. Common tools include the Global Acne Grading System (GAGS), the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score, the Leeds Revised Acne Grading, and the Truncal Acne Severity Scale (TRASS) [12]. Effective acne management requires a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach that addresses pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and individual preferences [4]. Topical retinoids remain the mainstay of therapy but may cause retinoid-induced dermatitis, necessitating careful use [13]. Dermocosmetics, or cosmeceuticals, are skincare formulations with active ingredients that combine cosmetic and therapeutic benefits [14]. These agents can serve as monotherapy in mild cases or can be used adjunctively in moderate-to-severe cases, enhancing both tolerability and adherence [15,16]. A structured skincare routine, particularly with effective cleansing agents, may augment therapeutic outcomes [17]. Patient education is essential for treatment success. Clinicians should discuss the chronic nature of acne, expected timelines, appropriate medication use, and the important of maintenance therapy. Understanding patient perspectives and tailoring treatments suited to their lifestyle can significantly improve adherence [18].

Evidence on acne management specific to the Indian subcontinent remains limited. This expert consensus seeks to address key gaps:

- Limited Indian data, with most existing research based on Western populations and possibly not reflecting Indian clinical and epidemiological nuances.

- A lack of comprehensive national guidelines that incorporate newer therapies and recommendations for special populations.

- Insufficient practical guidance to support real-world clinical decision-making.

- Unique clinical challenges in managing acne during pregnancy and lactation.

This consensus provides practical, evidence-based recommendations on the management of acne vulgaris to dermatologists and general physicians in India, including diagnosis, therapeutics, and special considerations such as care during pregnancy and lactation.

2. Results

Of the 61 clinical statements proposed, eight did not reach the predefined threshold of 75% agreement in the first round and were subsequently revised and discussed further. By the end of round two, 36 statements had been finalized. This iterative modified Delphi process ensured that the final recommendations reflected a balanced and evidence-informed expert consensus. The panel achieved agreement on several key aspects of acne vulgaris management in the Indian context, with an emphasis on individualized, patient-centric care. The finalized recommendations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expert recommendations on the diagnosis and management of acne in India.

3. Discussion

The expert discussion explored key findings on acne management, highlighting the efficacy and safety of various treatment options while addressing research gaps. The discussion below highlights key aspects of acne management, including treatment efficacy, challenges, and special considerations.

3.1. Baseline Investigations and Screening in Acne Vulgaris

Recommendations 1–5 addresses essential baseline investigations for individuals with acne vulgaris. Testing for serum triglycerides and alanine transaminase (ALT) is advised prior to initiating isotretinoin, given its known effects on lipid metabolism and liver function [13]. However, for patients with normal baseline values, routine repeat testing may not be necessary [43].

Culture and sensitivity testing in acne is typically reserved for severe, atypical, or treatment refractory cases or where secondary infection is suspected [44]. In female patients, particularly those with late-onset or treatment-resistant acne, hormonal evaluation is strongly recommended. A study reported that 45% of female acne patients who underwent pelvic ultrasound and blood testing were diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), highlighting the clinical importance of endocrinological evaluation in this population [45,46]. Insulin resistance, another metabolic factor, is also associated with acne pathogenesis and may warrant assessment [47]. For females of reproductive age, a pregnancy test is imperative prior to initiating isotretinoin due to its well-established teratogenic risks [20]. Additionally, while isotretinoin has been associated with rare psychiatric side effects, such as depression, psychological screening may be considered on a case-by-case basis [21].

|

3.2. Supportive Care and Lifestyle Management in Acne Vulgaris

Recommendations 6–9 emphasize the role of supportive and adjunctive strategies in the management of acne, including patient education. Given that acne is a chronic inflammatory condition, setting realistic expectations through patient education is crucial to promote treatment adherence and long-term success [23]. Patients should be informed about the nature of acne, anticipated treatment timelines, and the important of continued maintenance therapy.

Lifestyle factors, such as diet, sleep patterns, stress levels, and cosmetic product use, are increasingly being recognized as modifiable contributors to acne. Comprehensive history taking, including an assessment of the body mass index, obesity, and related factors, should be taken into account when identifying patients suitable for lifestyle management.

Incorporating dermocosmetics (cosmeceuticals) into daily skincare routine, including cleansers, moisturizers, and sunscreens, can enhance treatment tolerability and efficacy. These adjuncts help maintain skin barrier integrity, reduce irritation from topical medications, and improve overall satisfaction [26].

Emerging adjuncts such as probiotics have demonstrated the potential to reduce acne lesions and inflammation by modulating the skin microbiome [48]. On similar lines, a 2023 systematic review found that antioxidant supplements such as zinc, vitamin C, and nicotinamide may support skin health in acne-prone individuals, although further high-quality studies are needed to confirm their clinical benefit [49].

|

3.3. Topical Therapy for Acne Vulgaris

Topical retinoids: Recommendations 10–20 focus on topical therapies for acne vulgaris. Topical retinoids are widely regarded as first-line treatment options for mild-to-moderate acne due to their comedolytic, anti-inflammatory, and preventive effects on lesion formation. Among them, adapalene 0.1% is most preferred for its favorable efficacy and tolerability profile [27]. In comparison, tretinoin, though effective, may cause photosensitivity, erythema, and irritation [50]. Consequently, adapalene is often the preferred choice for patients with sensitive skin. A head-to-head study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of adapalene gel 0.1% vs. tretinoin cream 0.025% in patients with mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris found that adapalene demonstrated superior tolerability, with fewer cutaneous side effects [51].

Tazarotene, a synthetic retinoid recommended for moderate to severe acne, is well tolerated, safe, and effective but is associated with dryness and peeling. Its once-daily use and low concentration (0.05% [50 mg/g]) make it suitable for use in large areas such as the trunk [52]. However, it is associated with local irritation, which may affect adherence [53,54].

Trifarotene (0.005% or 50 mcg/g) is a fourth-generation retinoid that has shown promise in treating acne and PIH, particularly when combined with an appropriate skincare regimen. Clinical trials have demonstrated significantly greater lesion count reductions compared to vehicles at 12 weeks. Over 90% of patients reported high satisfaction with trifarotene, noting less dryness and irritation [55].

Topical retinoids are effective as monotherapy for mild-to-moderate acne. A systematic review confirmed the overall superiority of retinoids over a vehicle in improving acne severity. Improvements in Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) and Investigator’s Static Global Assessment scores ranged from 24.1 to 28.8% and 13.3 to 17.3%, respectively (p < 0.001). While no significant efficacy differences were found between tretinoin and Tazarotene, tolerability varied widely. Tretinoin 0.05% was associated with adverse events (AEs) in 62% of patients compared with 19% and 40% with adapalene 0.1% and 0.3%, respectively. Notably, more patients reported tolerable AEs with adapalene than with tazarotene (55.4% vs. 24.4%, p < 0.0012) [27].

In summary, all topical retinoids are effective, but their selection should be tailored to the patient’s skin type, anticipated response, and tolerability profile. Adapalene offers the best balance between efficacy and tolerability, tazarotene provides slightly greater efficacy but with higher irritation potential, and tretinoin shows relatively rapid results with intermediate tolerability.

Benzoyl peroxide: Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) is effective as a monotherapy for mild acne at concentrations of 2.5% and 5%. It is suitable for use on both facial and truncal acne and is valued for its antimicrobial activity against C. acnes, as well as its comedolytic and anti-inflammatory effects. BPO use does not lead to anti-microbial resistance, making it a cornerstone in both initial and maintenance acne therapy [27].

Topical antibiotics: In a recent study, 2% ozenoxacin, which was approved in India in 2022, demonstrated superior efficacy over clindamycin in reducing acne lesion severity and associated symptoms (p < 0.05) [56]. Topical 4% minocycline has also demonstrated good efficacy in treating inflammatory lesions of moderate-to-severe non-nodular acne vulgaris [57,58]. Minocycline 4% gel, which was approved in India in 2022, showed significantly greater reductions in acne lesions (−87.8% vs. −63.59%; p < 0.001) and a higher IGA treatment success (73.9% vs. 46.7%; p = 0.015) compared to clindamycin 1% at 12 weeks, along with better tolerability parameters versus the clindamycin 1% arm, supporting its use in treating moderate-to-severe acne in the Indian population [59].

Topical dapsone (5% or 7%) offers good antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties and is effective as monotherapy or in combination with isotretinoin. It is generally well tolerated, though mild, transient adverse effects such as dryness or localized eczema may occur [29]. New hydrogel-based formulations have improved its usability despite the molecule’s poor water solubility.

Given increasing concerns about antimicrobial resistance, non-antibiotic alternatives are gaining traction and preference. Azelaic acid 20% is once such agent, demonstrating significant reductions in acne lesion counts and severity with a favorable safety profile. It is particularly suitable for individuals with skin of color or those intolerant to retinoids [60]. Metronidazole, typically used in rosacea management, may also be effective in cases of moderate acne vulgaris [61]. Both 0.75% and 1.0% formulations, when used daily, are well tolerated and beneficial for steroid-induced or rosacea-like acne presentations [62].

Topical salicylic acid gel is a comedolytic and anti-inflammatory agent widely used in the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. In a randomized study involving 500 patients with mild-to-moderate acne, 2% supramolecular salicylic acid gel showed a 51.01% regression or a marked improvement in acne lesions at 12 weeks compared to 43.1% improvement with adapalene gel (p = 0.0831), with a lower AE rate (0.40% vs. 0.80%) and significant cosmetic benefits, including improved pore appearance [63].

Combination Therapy

Although BPO monotherapy is effective, fixed-dose combinations, particularly with topical retinoids, offer superior efficacy and patient adherence. The combination of adapalene and BPO can show reductions in acne lesions by up to 70.2%, with mild, self-resolving adverse effects as per a systematic review [33]. Clinical studies have shown that this combination produces significant improvements in as early as one week and is more effective than either component used alone [64,65,66]. It is also preferred for long-term maintenance therapy [27]. For moderate-to-severe acne, adapalene 0.3% combined with BPO 2.5% has demonstrated sustained efficacy, with improvements in both active lesions and atrophic scars maintained over 48 weeks [67,68,69].

In patients with Grade 4 acne, a combination of nadifloxacin 1% and adapalene 0.1% has shown to reduce acne severity significantly within 5 weeks and is generally well tolerated [70]. The CACTUS trial demonstrated that the combination of 0.1% adapalene and 1% clindamycin was well tolerated and more effective than monotherapies for moderate acne [71]. Similarly, the combination of 1.2% clindamycin phosphate with 0.025% tretinoin gel proved superior to monotherapy [72]. A study comparing the efficacy and safety of topical combinations showed a greater reduction in total lesion count with the clindamycin 1% and BPO 2.5% combination, while nadifloxacin 1% with BPO 2.5% had a better safety profile, both with statistically significant results [73].

When combined with BPO 2.5%, nadifloxacin 1% showed comparable efficacy with clindamycin 1%, significantly reducing total, inflammatory, and noninflammatory lesions [74]. To limit antimicrobial resistance, both topical and systemic antibiotics should be restricted to short-term use, ideally not exceeding three months [44,58]. Since adherence to acne therapy is often hindered by skin irritation, selecting agents with a favorable safety profile is essential to optimize outcomes and reduce dropout rates [54].

| Key expert recommendations |

| Adapalene 0.1% is the preferred choice of topical retinoid due to its favorable tolerability profile, followed by tretinoin 0.025% and adapalene 0.3%. Trifarotene, a fourth-generation retinoid, is effective and well tolerated for moderate facial and truncal acne, with additional benefits in treating PIH. For combination therapy, adapalene 0.1% remains the agent of choice, followed by adapalene 0.3% and tretinoin 0.025%.

|

3.4. Systemic Therapy in Acne Vulgaris

Recommendations 21–28 address the role of systemic therapy in acne management, particularly for patients with moderate-to-severe disease, the involvement of large body areas (e.g., the trunk), or poor response to topical treatments. Systemic therapy is also indicated for patients with nodulocystic or scarring acne, adult-onset acne, or acne associated with significant psychological distress [75].

Oral isotretinoin is considered the treatment of choice for severe, recalcitrant, or scarring acne. It is typically initiated at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day and may be titrated up to 1 mg/kg/day if tolerated well [22].

Although highly effective, isotretinoin is associated with several dose-dependent side effects, including xerosis (dry skin), cheilitis, musculoskeletal discomfort (e.g., back pain), transient elevations in liver enzymes, dyslipidemia, thrombocytopenia, insulin resistance, inflammatory bowel disease, and rarely, psychiatric symptoms such as insomnia or depression. Hair loss has been reported in 3.2% of patients at 0.3 mg/kg/day, increasing to 5.7% at 0.5 mg/kg/day.

To minimize the risk of flare-ups during treatment initiation, a conservative starting dose of ≤0.5 mg/kg/day is recommended. A cumulative dose of 120 mg/kg is generally considered both efficacious and safe. In cases of significant adverse events, temporary dose adjustments or treatment interruption may be warranted [13].

Oral antibiotics: Oral antibiotics are indicated for patients with moderate-to-severe acne, particularly when inflammatory lesions are prominent or the acne is non-responsive to topical treatments. Their use should be restricted to a maximum duration of 12 weeks to minimize the risk of antimicrobial resistance. Importantly, systemic antibiotics must always be combined with topical agents (e.g., BPO or retinoids) to improve efficacy and further reduce resistance development [44].

Tetracycline-class antibiotics—including doxycycline and minocycline—are widely preferred due to their dual antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. Doxycycline is preferred for moderate-to-severe acne, as it is effective and has the convenience of once-daily dosing (50–200 mg/day) for a duration of 6–8 weeks [76]. Minocycline is often favored for its better sebaceous gland penetration and fewer gastrointestinal disturbances than doxycycline [77]. Lymecycline is an optional antibiotic that can be considered, although its use is limited [78].

Macrolide antibiotics: Macrolides, such as erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin, are commonly prescribed for acne. However, increasing resistance to Cutibacterium acnes is a growing concern [79]. Azithromycin, often administered in a dosage of 500 mg thrice weekly, is reserved for patients intolerant to tetracyclines but carries a higher risk of resistance [44,77]. Treatment is usually limited to 12 weeks, with efforts to minimize duration whenever possible [80].

Third-line and alternative therapies: As a third-line therapy, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is effective in acne treatment but carries the risk of rare, severe AEs, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis [77]. It is generally reserved for cases where other antibiotics have failed.

Combination therapy: Combination therapies are often recommended to improve outcomes and reduce the development of resistance. Acne management guidelines suggest combining systemic therapies with topical treatments, such as BPO or retinoids [22].

Findings from a systematic review showed that combination therapy with a topical retinoid and an oral antibiotic resulted in significantly greater lesion count reduction compared with the vehicle treatment (64–78.9% vs. 41–56.8%; p < 0.001) [27].

As per a recent study, topical minocycline 4% in combination with oral isotretinoin was found to be more effective than oral isotretinoin in moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris [81].

The combination of benzoyl peroxide, a topical retinoid, and oral tetracycline demonstrated a treatment response rate ranging from 43% to 53%, indicating notable efficacy in the management of moderate-to-severe acne [82].

A prospective cross-sectional study found that a greater proportion of patients receiving combined oral and topical therapies achieved IGA scores of 0 or 1, indicating superior clinical improvement [83]. The concomitant use of topical benzoyl peroxide or a retinoid is recommended with systemic antibiotics for maintenance after completing antibiotic therapy [37].

Hormonal therapy: Acne in females often involves underlying metabolic or hormonal imbalances that may contribute to its persistence. A study of 135 Indian females with acne found that those with persistent acne exhibited significant clinical hyperandrogenism, PCOS, and hormonal imbalances, highlighting the need for endocrinological evaluation [46]. For hormonal acne in females, estrogen- and progestin-containing combined oral hormonal contraceptives (CoHCs) effectively treat acne due to their antiandrogenic properties and are suitable for patients seeking contraception [84].

Spironolactone is safe and effective for the long-term treatment of adult female acne, including truncal acne. The SAFA trial demonstrated that spironolactone (50 mg and 100 mg) was well tolerated with mild side effects. It is a viable alternative to oral antibiotics for females with persistent acne unresponsive to first-line topical therapies [85].

The addition of metformin can significantly reduce acne in patients with underlying metabolic or hormonal disorders, such as PCOS. Metformin may also be considered for patients who are non-responsive to standard acne treatments, particularly for those with insulin resistance or metabolic concerns [36].

Combining isotretinoin (0.5 mg/kg/day) with prednisolone (30 mg/day) should only be performed in the context of acne fulminans, and the experts gave a conditional recommendation for this [22].

Special situations: Intralesional triamcinolone injections (2.5 mg/mL–0.05 mL) may be considered for large acne lesions [22]. However, adverse effects, such as skin atrophy, were observed in fewer than 1% of patients [86].

|

3.5. Acne Management in Pregnancy and Lactation

Statement 29 gives recommendations on the medical therapies in pregnancy and lactation. Managing dermatologic conditions during pregnancy and lactation requires balancing treatment benefits with potential risks to the fetus or infant. Due to the lack of comprehensive guidelines on acne management in pregnancy and lactation, treatment must be individualized based on acne severity and the patient’s circumstances.

Preconception considerations: Although topical retinoids pose a low risk, they are best avoided during pregnancy as a precaution. Tretinoin is usually cleared from the body within a day in healthy, non-pregnant adults, though metabolism varies individually. Their use should be limited or discontinued before conception.

Therapies contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation:

Isotretinoin is strictly contraindicated due to its known teratogenic effects, and pregnancy should be avoided for six months after ceasing treatment. Individuals should also be counseled about the risks related to isotretinoin in pregnancy [87]. Spironolactone should also be discontinued at least 1 month to 6 weeks before conception due to its antiandrogenic effects. Additionally, dapsone and sulfamethoxazole are not indicated due to limited data regarding risks to the fetus [88]. Table 2 gives an overview of the drugs considered safe, contraindicated, or to be used with caution in pregnancy and lactation [88].

Table 2.

Overview of drugs in pregnancy and lactation.

Table 2.

Overview of drugs in pregnancy and lactation.

| Drug | Route of Administration | Pregnancy | Lactation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tretinoin | Topical | Contraindicated | Considered safe |

| Adapalene | Topical | Contraindicated | Use with caution |

| Benzoyl peroxide | Topical | Considered safe | Use with caution |

| Clindamycin | Topical and systemic | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Salicylic acid | Topical | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Dapsone | Topical | Not studied | Use with caution |

| Minocycline | Topical and systemic | Contraindicated | Considered safe for short-term use |

| Azelaic acid (<4%) | Topical | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Isotretinoin | Systemic | Contraindicated | Contraindicated |

| Azithromycin | Topical and systemic | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Erythromycin | Topical and systemic | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Penicillin | Topical and systemic | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Cephalosporins | Topical and systemic | Considered safe | Considered safe |

| Cotrimoxazole | Systemic | Contraindicated | Contraindicated |

| Spironolactone | Systemic | Contraindicated | Use with caution |

| Corticosteroids | Systemic | Contraindicated | Can be used; delay nursing by 3–4 h |

|

3.6. Complications of Acne Treatment: PIH, PIE, and Acne Scarring

Recommendations 30–34 cover the management of PIH and acne scars, focusing on effective treatments for hyperpigmentation that often follows acne. PIH and PIE (also known as acne-induced macular erythema) are considered cosmetically unacceptable by patients and may add to the psychosocial burden in individuals with acne.

Topical retinoids: Topical retinoids are recommended as a first-line treatment for patients with acne-associated PIH. Tretinoin 0.025% cream and adapalene 0.1% gel show significant improvement in treating acne and PIH in patients with skin of color; however, tretinoin may cause irritation and inflammation. Adapalene 0.3% gel effectively treats atrophic acne scars and improves skin texture, with good tolerability [42].

Skin-lightening agents: Hydroquinone is a key skin-lightening agent that may be combined with retinoids. However, it should be applied specifically to the affected areas in acne-related PIH to prevent unintended hypopigmentation [89]. A formulation containing 3% tranexamic acid, 1% kojic acid, and 5% niacinamide was shown to be a safe and effective treatment for PIH, demonstrating significant improvement in hyperpigmentation at week 12 compared to baseline [90]. Topical azelaic acid 20% cream and 5% tranexamic acid, also valuable options, were compared in a single-blind randomized trial, demonstrated comparable but statistically significant reductions in post-acne hyperpigmentation index (PAHI) measurements at week 12 compared to baseline [91].

Cosmeceuticals and adjunctive treatments: Cosmeceuticals containing ingredients such as salicylic acid, alpha-hydroxy acids, and niacinamide offer benefits when used as an adjunctive treatment for acne management [16]. These ingredients enhance the overall tolerability and effectiveness of acne and PIH treatments.

Sun protection and skincare: Broad-spectrum sunscreens with ultraviolet (UV) and visible light protection are essential for preventing the worsening of hyperpigmentation, and proper counseling on their use enhances treatment outcomes. A comprehensive skincare routine, including moisturizers, cleansers, and UV protection with physical sunscreen, can be particularly helpful in managing acne-induced PIH [39].

|

3.7. Retinoid-Induced Dermatitis

Statements 35–36 elaborate on retinoid-induced dermatitis. Retinoids are highly effective in treating acne and other dermatological conditions, but they may cause dose-dependent irritation in some patients, a condition known as retinoid dermatitis. Symptoms include erythema, pruritus, burning, xerosis, and desquamation [92].

The importance of skin tolerability: Ensuring optimal skin tolerability is essential for successful acne treatment. The CHARISMA study—a retrospective, multicenter study in India, demonstrated that adding a moisturizer with broad-spectrum sunscreen to acne treatment enhanced skin tolerability and patient satisfaction [93].

|

3.8. Maintenance Therapy

Individuals with frequent acne relapses after treatment are candidates for maintenance therapy. A fixed combination of topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide is recommended. If it is not tolerated or contraindicated, adapalene, azelaic acid, or benzoyl peroxide alone can be used. The need for maintenance therapy may be after 12 weeks [94].

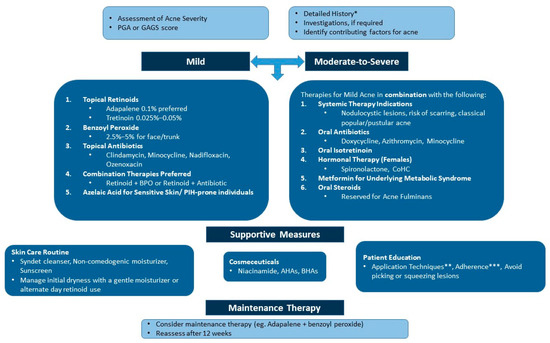

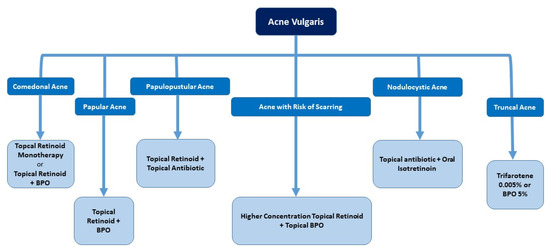

3.9. Algorithm for Diagnosis and Medical Management of Acne

Building on the above insights, the expert panel developed a practical algorithm for managing acne in the Indian population, emphasizing the need for tailored treatment approaches to balance effectiveness and skin comfort. Figure 1 provides a comprehensive diagnosis and management algorithm for acne based on expert consensus. Figure 2 gives a straightforward approach to choosing retinoid-based therapies based on acne lesions.

Figure 1.

An algorithm for the diagnosis and medical management of acne. AHA: alpha-hydroxy acid; BHA: beta-hydroxy acid; BPO: benzoyl peroxide; CoHC: combined oral hormonal contraceptive; GAGS: Global Acne Grading System; PGA: Physician’s Global Assessment; PIH: postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. * These can range from lifestyle factors, such as nutrition, stress, sleep, etc., to hormonal factors. ** A pea-sized amount of retinoids at night and the quantity of sunscreen to be applied. *** Encourage the consistent use of treatment modalities. Maintenance therapy is crucial after clearance.

Figure 2.

Retinoid-based therapies as per acne lesions. BPO: benzoyl peroxide.

4. Methodology

The consensus recommendations were developed through a structured, evidence-based process led by a panel of 14 dermatology experts, each with over 15 years of clinical experience and a strong record of academic contributions. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science to identify relevant studies on acne management, including general treatment strategies and special considerations during pregnancy and lactation. Studies published within the previous 5 and 10 years were considered eligible for inclusion.

The search strategy included both Medical Subject Headings and free-text keywords included “acne”, “acne treatment”, “medical management”, “retinoids”, “topical”, “oral antibiotics”, “systemic therapy”, “pregnancy”, “lactation”, “PIH”, “retinoid-induced dermatitis”, “cosmeceuticals”, and “dermocosmetics.” Relevant articles were selected following full-text screening to ensure a robust evidence base for discussion.

The next step involved the formulation of 61 key clinical statements, categorized into seven thematic domains:

- (I)

- Investigations for acne vulgaris;

- (II)

- Supportive care and lifestyle management in acne vulgaris;

- (III)

- Topical therapy in acne;

- (IV)

- Systemic therapy in acne;

- (V)

- Considerations in pregnancy and lactation;

- (VI)

- PIH and acne scarring;

- (VII)

- Retinoid-induced dermatitis.

Each statement was graded using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Oxford level of evidence [95].

The consensus process utilized a modified Delphi technique, with two rounds of anonymous voting conducted on a virtual platform. The responses were collected anonymously. Experts consented to the aggregate analysis of their responses. Consensus was defined as ≥75% agreement on a 5-point Likert scale. Statements were then categorized into positive recommendations, where ≥75% of participants agreed or strongly agreed, or negative recommendations, where ≥75% disagreed or strongly disagreed. Statements with 50–74% agreement were considered to have near consensus, while those with <50% agreement were classified as having no consensus. Statements not achieving 75% concordance were revisited for further discussion.

5. Conclusions

This consensus provides comprehensive, evidence-based recommendations for diagnosing and managing acne vulgaris in India. The expert panel has established practical guidance for dermatologists and general practitioners by addressing key clinical domains, including baseline investigations, treatment strategies, skincare, and special considerations, such as pregnancy and PIH. Additionally, the proposed algorithm offers a structured approach to optimizing acne management, ensuring better patient outcomes through individualized and informed decision-making.

Author Contributions

N.M., A.S. and A.N. contributed to the conceptualization and study design; N.M., A.S., A.N., P.S., S.K.R., S.A., S.K.A. and S.D.A. contributed to the data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing; D.J., L.K.G., M.K., M.R.P., R.N., S.D., D.D., A.B., S.P. and H.B. contributed to the interpretation of the analyzed data for this work. All authors contributed to the critical evaluation of data for intellectual content and reviewing the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable in all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This consensus statement was funded by Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited through an unrestricted educational grant. The design and content of this manuscript was in no way influenced by Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), research involving “educational practices such as instructional strategies or effectiveness of or the comparison among instructional techniques, curricula, or classroom management methods” may be exempt from ethics committee review. Based on this guidance, our study does not require approval from an ethics committee. According to the ICMR guidelines, studies involving instructional methods or curriculum comparisons may be exempt from ethics committee review. As our consensus process aligns with this category, ethical approval is not required. Furthermore, since it involves minimal risk and no direct participant interaction, the ICMR permits a waiver of informed consent. This work was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank BioQuest Solutions Pvt. Ltd. for their support with medical writing.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dhiraj Dhoot, Ashwin Balasubramanian, Saiprasad Patil and Hanmant Barkate are employed by the company Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Titus, S.; Hodge, J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acne. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 86, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.; Shukla, R.; Chaudhari, P.; Patil, S.; Patil, A.; Nadkarni, N.; Goldust, M. Prevalence of Acne Vulgaris and Its Clinico-Epidemiological Pattern in Adult Patients: Results of a Prospective, Observational Study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3672–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurat, J.-H.; Halioua, B.; Baissac, C.; Cullell, N.P.; Ben Hayoun, Y.; Aroman, M.S.; Taieb, C.; Skayem, C. Epidemiology of Acne and Rosacea: A Worldwide Global Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1016–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budamakuntla, L.; Parasramani, S.; Dhoot, D.; Deshmukh, G.; Barkate, H. Acne in Indian Population: An Epidemiological Study Evaluating Multiple Factors. IP Indian J. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 6, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E.; Dreno, B.; Lucky, W.A.; Agak, W.G.; Dokras, A.; Kim, J.J.; Lobo, R.A.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Dumesic, D. Female Adult Acne and Androgen Excess: A Report from the Multidisciplinary Androgen Excess and PCOS Committee. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6, bvac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Ward, M.; Gooderham, M. Dermatology: How to Manage Acne in Skin of Colour. Drugs Context 2022, 11, 2021-10-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.M.; Sridharan, R. Factors Aggravating or Precipitating Acne in Indian Adults: A Hospital-Based Study of 110 Cases. Indian J. Dermatol. 2018, 63, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, J.S.; Fathima, S.; Ameera, S.; Muhammed, K. Clinical Profile of Acne Vulgaris: An Observational Study from a Tertiary Care Institution in Northern Kerala, India. Int. J. Res. Dermatol. 2019, 5, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekore, R.I.; Ekore, J.O. Excoriation (Skin-Picking) Disorder among Adolescents and Young Adults with Acne-Induced Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation and Scars. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 1488–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.A.; Khunger, N. A Morphological Study of Acne Scarring and Its Relationship between Severity and Treatment of Active Acne. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2020, 13, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, S.; Sawant, N.S.; Mahajan, S. Depression, Body Image and Quality of Life in Acne Scars. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, I.H.; Kwak, J.H.; Na, C.H.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, B.S.; Choi, H. A Comprehensive Review of the Acne Grading Scale in 2023. Ann. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, I.; Anjankar, V.P. Side Effects of Treating Acne Vulgaris with Isotretinoin: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e55946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, C.L.; Noppakun, N.; Micali, G.; Azizan, N.Z.; Boonchai, W.; Chan, Y.; Cheong, W.K.; Chiu, P.C.; Etnawati, K.; Gulmatico-Flores, Z.; et al. Meeting the Challenges of Acne Treatment in Asian Patients: A Review of the Role of Dermocosmetics as Adjunctive Therapy. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2016, 9, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araviiskaia, E.; Dréno, B. The Role of Topical Dermocosmetics in Acne Vulgaris. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, I.; Kobayashi, M.; Nomura, Y.; Abe, M.; Kerob, D.; Dreno, B. The Role and Benefits of Dermocosmetics in Acne Management in Japan. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, K.; Fields, K.; Falla, T.J. Efficacy of a Twice-Daily, 3-Step, over-the-Counter Skincare Regimen for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Jawade, S.; Madke, B.; Gupta, S. Recent Trends in the Management of Acne Vulgaris: A Review Focusing on Clinical Studies in the Last Decade. Cureus 2024, 16, e56596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emtenani, S.; Abdelghaffar, M.; Ludwig, R.J.; Schmidt, E.; Kridin, K. Risk and Timing of Isotretinoin-Related Laboratory Disturbances: A Population-Based Study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ipledge-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategy-rems (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Tan, N.K.W.; Tang, A.; MacAlevey, N.C.Y.L.; Tan, B.K.J.; Oon, H.H. Risk of Suicide and Psychiatric Disorders among Isotretinoin Users: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.V.; Yeung, H.; Cheng, C.E.; Cook-Bolden, F.; Desai, S.R.; Druby, K.M.; Freeman, E.E.; Keri, J.E.; Stein Gold, L.F.; Tan, J.K.L.; et al. Guidelines of Care for the Management of Acne Vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1006.e1–1006.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, L.; Lv, M.; Yue, N.; Fei, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. The Relevant of Sex Hormone Levels and Acne Grades in Patients with Acne Vulgaris: A Cross-Sectional Study in Beijing. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, A.; Muller, I.; Geraghty, A.W.A.; Platt, D.; Little, P.; Santer, M. Views and Experiences of People with Acne Vulgaris and Healthcare Professionals about Treatments: Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammari, A.; Kerob, D.; Demessant, A.L.; Nioré, M.; Dréno, B. A Dermocosmetic Regimen Is Able to Mitigate Skin Sensitivity Induced by a Retinoid-Based Fixed Combination Treatment for Acne: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Guideline Alliance (UK). Skin Care Advice for People with Acne Vulgaris; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kolli, S.S.; Pecone, D.; Pona, A.; Cline, A.; Feldman, S.R. Topical Retinoids in Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauk, L. Acne Vulgaris: Treatment Guidelines from the AAD. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 95, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F. Efficacy and Safety of Dapsone Gel for Acne: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyachi, Y.; Yamasaki, K.; Fujita, T.; Fujii, C. Metronidazole Gel (0.75%) in Japanese Patients with Rosacea: A Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled, Phase 3 Study. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucheng, H.; Zhou, X.; Du, D.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Jiang, X. Effects of 15% Azelaic Acid Gel in the Management of Post-Inflammatory Erythema and Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Acne Vulgaris. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 1293–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein Gold, L.; Lain, E.; Del Rosso, J.Q.; Gold, M.; Draelos, Z.D.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Sadick, N.; Werschler, W.P.; Gooderham, M.J.; Lupo, M. Clindamycin Phosphate 1.2%/Adapalene 0.15%/Benzoyl Peroxide 3.1% Gel for Moderate-to-Severe Acne: Efficacy and Safety Results from Two Randomized Phase 3 Trials. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, K.; Sakina, S.; Mumtaz, S.; Behram, F.; Akbar, A.; Jadoon, S.K.; Tasneem, S. Safety and Efficacy of Fixed-Dose Combination of Adapalene and Benzoyl Peroxide in Acne Vulgaris Treatment: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Cureus 2024, 16, e69341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xue, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhong, J.; Shao, X.; Chen, J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Acne Scars in Patients with Acne Vulgaris. Skin Res. Technol. 2023, 29, e13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.K.; Shinkai, K.; Murase, J.E. A Review of Hormone-Based Therapies to Treat Adult Acne Vulgaris in Women. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2017, 3, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, L.; Szybiak-Skora, W.; Sadowska-Przytocka, A.; Zaba, R.; Wieckowska, B.; Lacka, K. Metformin Therapy for Acne Vulgaris: A Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaenglein, A.L.; Pathy, A.L.; Schlosser, B.J.; Alikhan, A.; Baldwin, H.E.; Berson, D.S.; Bowe, W.P.; Graber, E.M.; Harper, J.C.; Kang, S.; et al. Guidelines of Care for the Management of Acne Vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 945–973.e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiboutot, D.; Layton, A.M.; Traore, I.; Gontijo, G.; Troielli, P.; Ju, Q.; Kurokawa, I.; Dreno, B. International Expert Consensus Recommendations for the Use of Dermocosmetics in Acne. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.G.; Kim, W.B.; Jo, C.E.; Nabieva, K.; Kirshen, C.; Ortiz, A.E. Topical Treatment for Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation: A Systematic Review. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2022, 33, 2518–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, K.; Khalid, B.; Maazi, M.; Ahmed, R.; Wang, O.J.E.; Khosravi-Hafshejani, T. Treatment of Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Skin of Colour: A Systematic Review. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2024, 28, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, M.J.; Leung, S.; Chien, A.; Kerrouche, N.; Fischer, A.H.; Kang, S. Adapalene 0.3% Gel Shows Efficacy for the Treatment of Atrophic Acne Scars. Dermatol. Ther. 2018, 8, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, J.-A.; Chavda, R.; Kon, K.M.; Goodman, G.J.; Oblepias, M.S.; Nadela, R.E.; Oon, H.H.; Aurangabadkar, S.; Suh, D.H.; Chan, H.H.L.; et al. A Review of the Topical Management of Acne and Its Associated Sequelae in the Asia-Pacific Region with a Spotlight on Trifarotene. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajaji, A.; Alrawaf, F.A.; Alosayli, S.I.; Alqifari, H.N.; Alhabdan, B.M.; Alnasser, M.A. Laboratory Abnormalities in Acne Patients Treated with Oral Isotretinoin: A Retrospective Epidemiological Study. Cureus 2021, 13, e19031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, H. Acne, the Skin Microbiome, and Antibiotic Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardana, K.; Bansal, P.; Sharma, L.K.; Garga, U.C.; Vats, G. A Study Comparing the Clinical and Hormonal Profile of Late Onset and Persistent Acne in Adult Females. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta-Ambalal, S. Clinical, Biochemical, and Hormonal Associations in Female Patients with Acne: A Study and Literature Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.R.; Khare, J.; Saxena, A.; Jindal, S. Correlation between Acne and Insulin Resistance; Experience from Central India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutema, I.A.M.P.; Latarissa, I.R.; Widowati, I.G.A.R.; Sartika, C.R.; Ciptasari, N.W.E.; Lestari, K. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplements and Topical Applications in the Treatment of Acne: A Scoping Review of Current Results. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, J.T.; Diaz, M.J.; Rodriguez, D.; Kleinberg, G.; Aflatooni, S.; Palreddy, S.; Abdi, P.; Taneja, K.; Batchu, S.; Forouzandeh, M. Evidence-Based Utility of Adjunct Antioxidant Supplementation for the Prevention and Treatment of Dermatologic Diseases: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.H. Exploring Acne Treatments: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Emerging Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemani, U.; Khopkar, U.; Nayak, C. A Comparison Study of the Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Topical Adapalene Gel (0.1%) and Tretinoin Cream (0.025%) in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 5, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenfield, L.; Kwong, P.; Lee, S.; Krowchuk, D.; Arekapudi, K.; Hebert, A. Advances in Topical Management of Adolescent Facial and Truncal Acne: A Phase 3 Pooled Analysis of Safety and Efficacy of Trifarotene 0.005% Cream. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Peytavi, U.; Fowler, J.; Kemény, L.; Draelos, Z.; Cook-Bolden, F.; Dirschka, T.; Eichenfield, L.; Graeber, M.; Ahmad, F.; Alió Saenz, A.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Trifarotene 50 Μg/g Cream, a First-in-Class RAR-γ Selective Topical Retinoid, in Patients with Moderate Facial and Truncal Acne. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevimli Dikicier, B. Topical Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: Efficiency, Side Effects, and Adherence Rate. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 2987–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, A.; Del Rosso, J.Q.; Forman, S.; Martorell, A.; Browning, J.; Laquer, V.; Desai, S.R.; York, J.P.; Chavda, R.; Dhawan, S.; et al. Importance of Treating Acne Sequelae in Skin of Color: 6-Month Phase IV Study of Trifarotene with an Appropriate Skincare Routine Including UV Protection in Acne-Induced Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingaraja, M.M.; Rahul, H.V. Comparative Study of Topical Ozenoxacin vs Topical Clindamycin in Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shemer, A.; Shiri, J.; Mashiah, J.; Farhi, R.; Gupta, A.K. Topical Minocycline Foam for Moderate to Severe Acne Vulgaris: Phase 2 Randomized Double-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled Study Results. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 74, 1251–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallo, M.; Patel, K.; Hebert, A.A. Topical Antibiotic Treatment in Dermatology. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Mistry, D.; Gonsalves, N.; Vasani, P.; Dhoot, D.; Barkate, H. A Prospective, Randomized, Comparative Study of Topical Minocycline Gel 4% with Topical Clindamycin Phosphate Gel 1% in Indian Patients with Acne Vulgaris. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, S.; Campbell, J.; Rowe, R.; Daly, M.-L.; Moncrieff, G.; Maybury, C. A Systematic Review to Evaluate the Efficacy of Azelaic Acid in the Management of Acne, Rosacea, Melasma and Skin Aging. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 2650–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaeiani, E.; Fouladi, R.F.; Yousefi, N.; Amirnia, M.; Babaeinejad, S.; Shokri, J. Efficacy of 2% Metronidazole Gel in Moderate Acne Vulgaris. Indian J. Dermatol. 2012, 57, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, S.K.; Kumrah, L. Topical Corticosteroid-Induced Rosacea-like Dermatitis: A Clinical Study of 110 Cases. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2011, 77, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.X.; Yi, J.; Su, Z.; Gao, X.; Jiang, X.; Yu, N.; Xiang, L.; Zeng, W.; Li, J.; Jin, H.; et al. 2% Supramolecular Salicylic Acid Hydrogel vs. Adapaline Gel in Mild to Moderate Acne Vulgaris Treatment: A Multicenter, Randomized, Evaluator-Blind, Parallel-Controlled Trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 2125–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geetha, A.; Vishaka; Raghav, M.V.; Asha, G.S. A Comparative Study of Efficacy and Tolerability of Topical Benzoyl Peroxide versus Topical Benzoyl Peroxide with Adapalene in Mild to Moderate Acne. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 85, 1534–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Jawade, S.A.; Saigaonkar, V.A.; Kondalkar, A.R. Efficacy and Tolerability of Adapalene 0.1%-Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Combination Gel in Treatment of Acne Vulgaris in Indian Patients: A Randomized Investigator-Blind Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Dermatol. 2016, 19, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Gollnick, H.P.M.; Loesche, C.; Ma, Y.M.; Gold, L.S. Synergistic Efficacy of Adapalene 0.1%-Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% in the Treatment of 3855 Acne Vulgaris Patients. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2011, 22, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Yogendra, M.; Gaurkar, S.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Sen, D.; Jadhwar, S. Investigating the Use of 0.3% Adapalene/2.5% Benzoyl Peroxide Gel for the Management of Moderate-to-Severe Acne in Indian Patients: A Phase 4 Study Assessing Safety and Efficacy. Cureus 2024, 16, e65894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dréno, B.; Bissonnette, R.; Gagné-Henley, A.; Barankin, B.; Lynde, C.; Chavda, R.; Kerrouche, N.; Tan, J. Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of up to 48 Weeks’ Treatment with Topical Adapalene 0.3%/Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Gel in the Prevention and Reduction of Atrophic Acne Scars in Moderate and Severe Facial Acne. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Bissonnette, R.; Gagné-Henley, A.; Barankin, B.; Lynde, C.; Kerrouche, N.; Tan, J. Prevention and Reduction of Atrophic Acne Scars with Adapalene 0.3%/Benzoyl Peroxide 2.5% Gel in Subjects with Moderate or Severe Facial Acne: Results of a 6-Month Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Trial Using Intra-Individual Comparison. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeister, C.; Bödeker, R.-H.; Schwantes, U.; Borelli, C. Impact of Parallel Topical Treatment with Nadifloxacin and Adapalene on Acne Vulgaris Severity and Quality of Life: A Prospective, Uncontrolled, Multicentric, Noninterventional Study. Biomed. Hub 2021, 6, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Yang, W.L.; Yin, J.W.; Deng, L.H.; Chen, B.; Liu, H.W.; Zhang, S.M.; Han, J.D.; Liu, Z.J.; Dai, X.R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Fixed-Dose Combination Gel with Adapalene 0.1% and Clindamycin 1% for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris (CACTUS): A Randomized, Controlled, Assessor-Blind, Phase III Clinical Trial. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 3097–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsendorf, F. Clindamycin Phosphate 1.2%/Tretinoin 0.025%: A Novel Fixed-Dose Combination Treatment for Acne Vulgaris. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29 (Suppl. S5), 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Sehgal, V.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Singh, S.P. A Comparative Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Combination Topical Preparations in Acne Vulgaris. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2015, 5, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Sarkar, D.K.; Dutta, R.N. Efficacy and Safety of Topical Nadifloxacin and Benzoyl Peroxide versus Clindamycin and Benzoyl Peroxide in Acne Vulgaris: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2011, 43, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.; Barankin, B.; Lam, J.M.; Leong, K.F.; Hon, K.L. Dermatology: How to Manage Acne Vulgaris. Drugs Context 2021, 10, 2021-8-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, S.K. Acne Vulgaris Treatment: The Current Scenario. Indian J. Dermatol. 2011, 56, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, H. Oral antibiotic treatment options for acne vulgaris. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2020, 13, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Hekmatjah, J.; Kircik, L.H. Oral Tetracyclines and Acne: A Systematic Review for Dermatologists. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2020, 19, s6–s13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.M.; Marto, J.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Graber, E.M. A Review of Systemic Minocycline Side Effects and Topical Minocycline as a Safer Alternative for Treating Acne and Rosacea. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardeh, S.; Saki, N.; Jowkar, F.; Kardeh, B.; Moein, S.A.; Khorraminejad-Shirazi, M.H. Efficacy of Azithromycin in Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Mini Review. World J. Plast. Surg. 2019, 8, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Halder, S.; Dhoot, D.; Balasubramanian, A.; Barkate, H. A Prospective, Randomised Comparative Study to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Topical Minocycline Gel 4% plus Oral Isotretinoin against Oral Isotretinoin Only in Indian Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Acne Vulgaris. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2025, 42, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavranezouli, I.; Daly, C.H.; Welton, N.J.; Deshpande, S.; Berg, L.; Bromham, N.; Arnold, S.; Phillippo, D.M.; Wilcock, J.; Xu, J.; et al. A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Topical Pharmacological, Oral Pharmacological, Physical and Combined Treatments for Acne Vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kher, M.; Nuzhat, Q.; Passi, S. Drug Utilization Patterns and Adherence in Patients on Systemic and Topical Medications for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Int. J. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. 2025, 14, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Gosnell, E.; Karatas, T.B.; Deitelzweig, C.; Collins, E.M.B.; Yeung, H. Hormonal Therapies for Acne: A Comprehensive Update for Dermatologists. Dermatol. Ther. 2025, 15, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santer, M.; Lawrence, M.; Renz, S.; Eminton, Z.; Stuart, B.; Sach, T.H.; Pyne, S.; Ridd, M.J.; Francis, N.; Soulsby, I.; et al. Effectiveness of Spironolactone for Women with Acne Vulgaris (SAFA) in England and Wales: Pragmatic, Multicentre, Phase 3, Double Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2023, 381, e074349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, T.; Taliercio, M.; Nia, J.K.; Hashim, P.W.; Zeichner, J.A. Dermatologist Use of Intralesional Triamcinolone in the Treatment of Acne. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), Government of India. Safety Guidelines for Isotretinoin. Available online: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2018/UploadPublic_NoticesFiles/Isotretinoin19dec18.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ly, S.; Kamal, K.; Manjaly, P.; Barbieri, J.S.; Mostaghimi, A. Treatment of Acne Vulgaris during Pregnancy and Lactation: A Narrative Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, V.D.; Baldwin, H.; Cook-Bolden, F.E.; Alexis, A.F.; Stein Gold, L.; Guenin, E. Effects of Topical Retinoids on Acne and Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients with Skin of Color: A Clinical Review and Implications for Practice. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Ayres, E.; Bak, H.; Manco, M.; Lynch, S.; Raab, S.; Du, A.; Green, D.; Skobowiat, C.; Wangari-Talbot, J.; et al. Effect of a Tranexamic Acid, Kojic Acid, and Niacinamide Containing Serum on Facial Dyschromia: A Clinical Evaluation. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2019, 18, 454–459. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhan, M.; Talebi-Ghane, E.; Poostiyan, E. A Comparative Study of 20% Azelaic Acid Cream versus 5% Tranexamic Acid Solution for the Treatment of Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients with Acne Vulgaris: A Single-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2023, 28, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsa, A.C.; Suhandi, C.; Afidika, J.; Ghaliya, S.; Elamin, K.M.; Wathoni, N. A Comprehensive Review of the Strategies to Reduce Retinoid-Induced Skin Irritation in Topical Formulation. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 5551774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Deshmukh, G.A.; Dhoot, D.S.; Barkate, H. Comprehensive Skin Care Regimen of Moisturizer with Broad-Spectrum Sunscreen as an Adjuvant in Management of Acne (CHARISMA). Int. J Sci. Stud. 2018, 6, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acne Vulgaris: Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on 2 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).