Antibiotic Resistance Awareness in Kosovo: Insights from the WHO Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participants’ Demographics

2.2. Proper Antibiotic Use and AMR Awareness

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Study Participants

4.3. Participant Recruitment and Sample Size

4.4. Data Collection

4.5. Data Analysis

4.6. Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Nanayakkara, A.K.; Boucher, H.W.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Jezek, A.; Outterson, K.; Greenberg, D.E. Antibiotic resistance in the patient with cancer: Escalating challenges and paths forward. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Hollis, A. The effect of antibiotic usage on resistance in humans and food-producing animals: A longitudinal, One Health analysis using European data. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1170426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kraker, M.E.A.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2020, 13, e1002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Phulgenda, S.; Antoniou, P.; Wong, D.L.F.; Iwamoto, K.; Kandelaki, K. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antimicrobial resistance among general public across 14 member states in the WHO European region: Results from a cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1274818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.A.; Vlieghe, E.; Mendelson, M.; Wertheim, H.; Ndegwa, L.; Villegas, M.V.; Gould, I.; Levy Hara, G. Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: The same but different? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakul, D.; Joksimović, B.; Milić, M.; Radanović, M.; Dukić, N.; Lalović, N.; Nischolson, D.; Mijović, B.; Sokolović, D. Public knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance in Eastern Region of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the COVID-19 pandemic. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Veterinary Antimicrobials in Europe’s Environment: A One Health Perspective. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/veterinary-antimicrobials-in-europes-environment (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Delpy, L.; Astbury, C.C.; Aenishaenslin, C.; Ruckert, A.; Penney, T.L.; Wiktorowicz, M.; Ciss, M.; Benko, R.; Bordier, M. Integrated surveillance systems for antibiotic resistance in a One Health context: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yopa, D.S.; Massom, D.M.; Kiki, G.M.; Sophie, R.W.; Fasine, S.; Thiam, O.; Zinaba, L.; Ngangue, P. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of One Health strategies in developing countries: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1252428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Commission; European Food Safety Authority. ECDC/EC/EFSA Country Visit to Kosovo to Advance One Health Responses Against Antimicrobial Resistance. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/ecdcecefsa-country-visit-kosovo-advance-one-health-responses-against (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Coombs, N.C.; Campbell, D.G.; Caringi, J. A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers’ views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajmi, D.; Berisha, M.; Begolli, I.; Hoxha, R.; Mehmeti, R.; Mulliqi-Osmani, G.; Kurti, A.; Loku, A.; Raka, L. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use in Kosovo. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, E.; Giovanetti, M.; Benedetti, F.; Scarpa, F.; Johnston, C.; Borsetti, A.; Ceccarelli, G.; Azarian, T.; Zella, D.; Ciccozzi, M. Joining forces against antibiotic resistance: The One Health solution. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhadry, S.W.; Tahoon, M.A.H. Health literacy and its association with antibiotic use and knowledge of antibiotics among Egyptian population: Cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otaigbe, I.I.; Elikwu, C.J. Drivers of inappropriate antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, A.J.; Edwards, G.; Santillo, M.; Wanat, M.; Glogowska, M.; Butler, C.C.; Walker, A.S.; Hayward, G.; Tonkin-Crine, S. Re-examining advice to complete antibiotic courses: A qualitative study with clinicians and patients. BJGP Open 2023, 7, BJGPO.2022.0170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupi, A.; Raka, D.; Kaae, S.; Sporrong, S.K. Culture of antibiotic use in Kosovo—An interview study with patients and health professionals. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 17, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: A Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balea, L.B.; Gulestø, R.J.A.; Xu, H.; Glasdam, S. Physicians’, pharmacists’, and nurses’ education of patients about antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance in primary care settings: A qualitative systematic literature review. Front. Antibiot. 2025, 3, 1507868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amábile-Cuevas, C.F. Myths and misconceptions around antibiotic resistance: Time to get rid of them. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 54, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muteeb, G.; Rehman, M.T.; Shahwan, M.; Aatif, M. Origin of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance, and their impacts on drug development: A narrative review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-López, M.; Carrillo-Quiróz, B.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet. World 2022, 15, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/194460/9789241509817_eng.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

| Characteristic | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Albanian, Other | 549 (96.6%), 19 (3.4%) |

| Gender | Male, Female | 340 (59.9%), 228 (40.1%) |

| Residence | Urban, Suburban, Rural | 340 (59.9%), 179 (31.5%), 49 (8.6%) |

| Age Group | 16–18, 19–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65+ | 47 (8.2%), 86 (15.1%), 144 (25.4%), 115 (20.2%), 106 (18.6%), 53 (9.4%), 18 (3.2%) |

| Education Level | No schooling, <HS, HS, Some college, Associate, Bachelor, Master+, Doctorate | 22 (3.9%), 55 (9.7%), 206 (36.2%), 86 (15.2%), 27 (4.8%), 120 (21.2%), 48 (8.5%), 3 (0.5%) |

| Monthly Income (EUR) | <170, 170–250, 250–350, 350–650, 650–850, 850–1000, >1000 | 47 (8.2%), 57 (10.0%), 122 (21.5%), 156 (27.5%), 75 (13.3%), 34 (6.0%), 77 (13.6%) |

| Household Type | Multi-adult w/o children, w/children; Married/domestic w/or w/o children; Single, Single w/children | 153 (27.0%), 137 (24.2%), 89 (15.6%), 74 (13.0%), 77 (13.6%), 38 (6.7%) |

| Outcome | Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

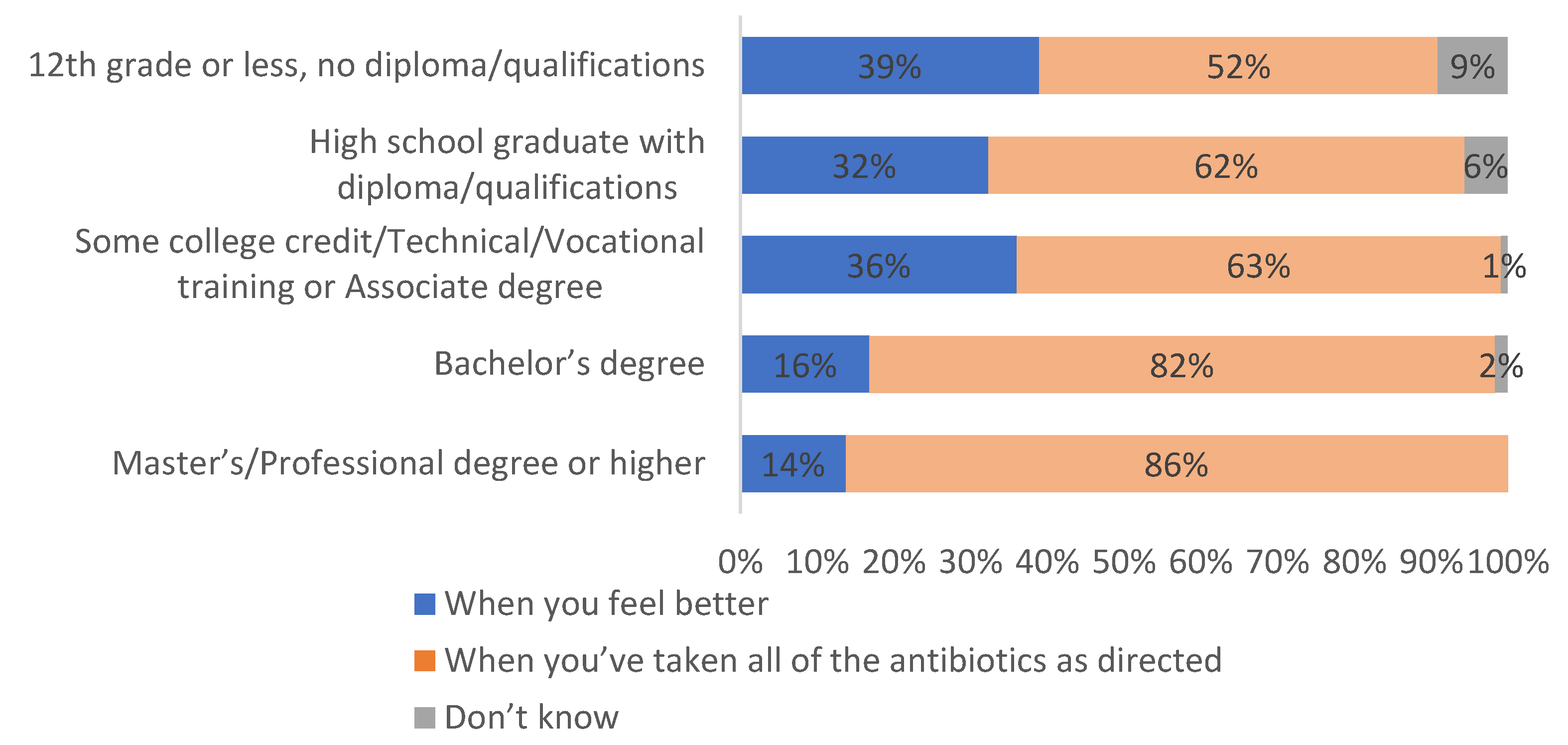

| Correct belief: Complete full course of antibiotics (Figure 3) | Female (vs. Male) | 2.05 | [1.40, 3.01] | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s+ (vs. ≤High School) | 2.87 | [1.89, 4.36] | <0.001 | |

| Correct belief: Do not use antibiotics prescribed to others (Figure 4) | Female (vs. Male) | 1.81 | [1.23, 2.67] | 0.003 |

| Bachelor’s+ (vs. ≤High School) | 2.45 | [1.60, 3.76] | <0.001 | |

| Incorrect belief: Reuse previously effective antibiotics (Figure 5) | Master’s+ (vs. ≤High School) | 0.28 | [0.14, 0.56] | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pasha, F.; Krasniqi, V.; Ismaili, A.; Krasniqi, S.; Bahtiri, E.; Qorraj Bytyqi, H.; Kolshi Krasniqi, V.; Krasniqi, B. Antibiotic Resistance Awareness in Kosovo: Insights from the WHO Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14060599

Pasha F, Krasniqi V, Ismaili A, Krasniqi S, Bahtiri E, Qorraj Bytyqi H, Kolshi Krasniqi V, Krasniqi B. Antibiotic Resistance Awareness in Kosovo: Insights from the WHO Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(6):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14060599

Chicago/Turabian StylePasha, Flaka, Valon Krasniqi, Adelina Ismaili, Shaip Krasniqi, Elton Bahtiri, Hasime Qorraj Bytyqi, Valmira Kolshi Krasniqi, and Blana Krasniqi. 2025. "Antibiotic Resistance Awareness in Kosovo: Insights from the WHO Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey" Antibiotics 14, no. 6: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14060599

APA StylePasha, F., Krasniqi, V., Ismaili, A., Krasniqi, S., Bahtiri, E., Qorraj Bytyqi, H., Kolshi Krasniqi, V., & Krasniqi, B. (2025). Antibiotic Resistance Awareness in Kosovo: Insights from the WHO Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public Awareness Survey. Antibiotics, 14(6), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14060599