Public Awareness and Perceptions of Antibiotic Use in Human and Veterinary Medicine in Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Attitudes Towards the Use of Antibiotics

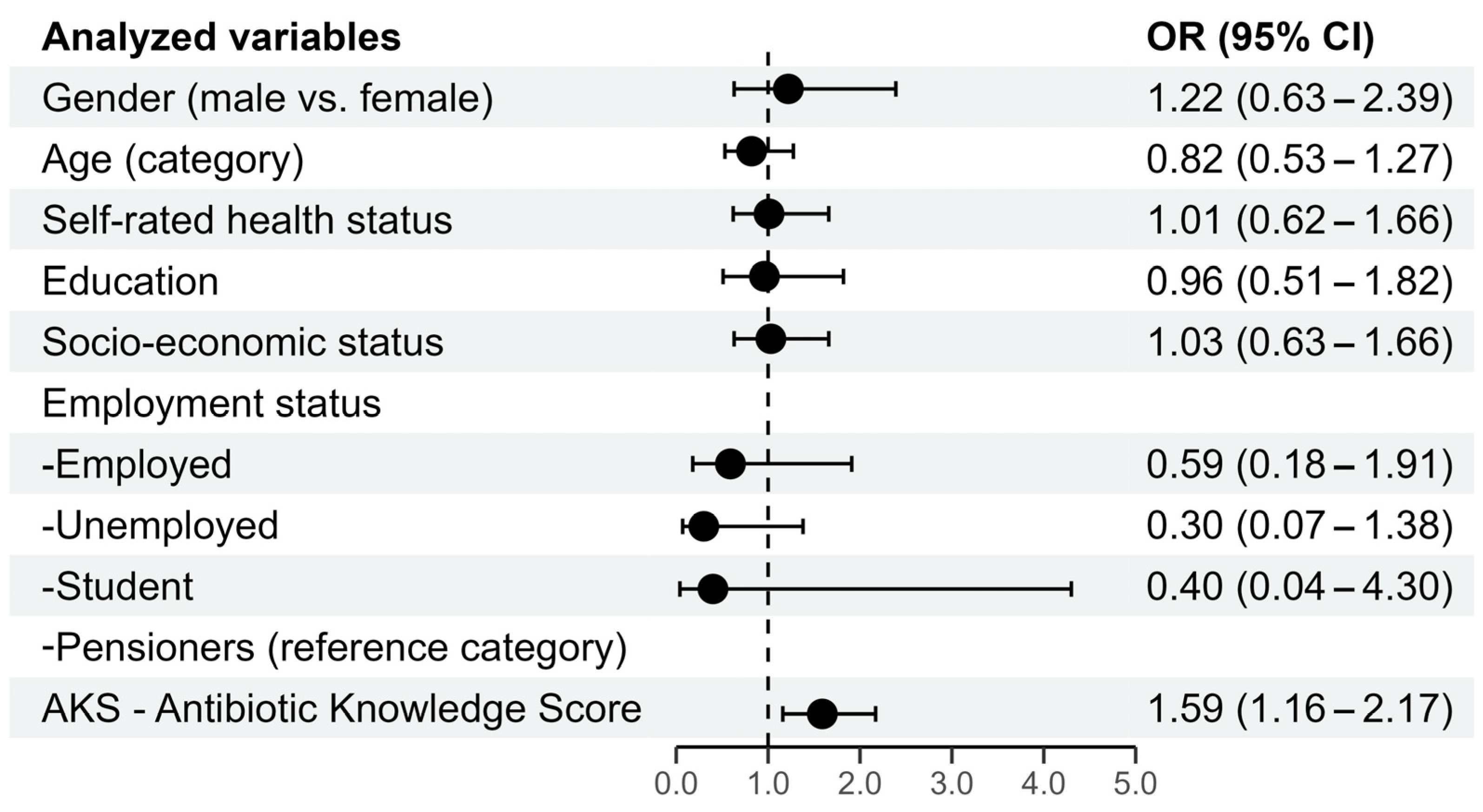

2.1.1. Predictors of the Desirable Attitude Towards Antibiotics Usage

2.1.2. Attitude About the Cessation of Antibiotic Treatment

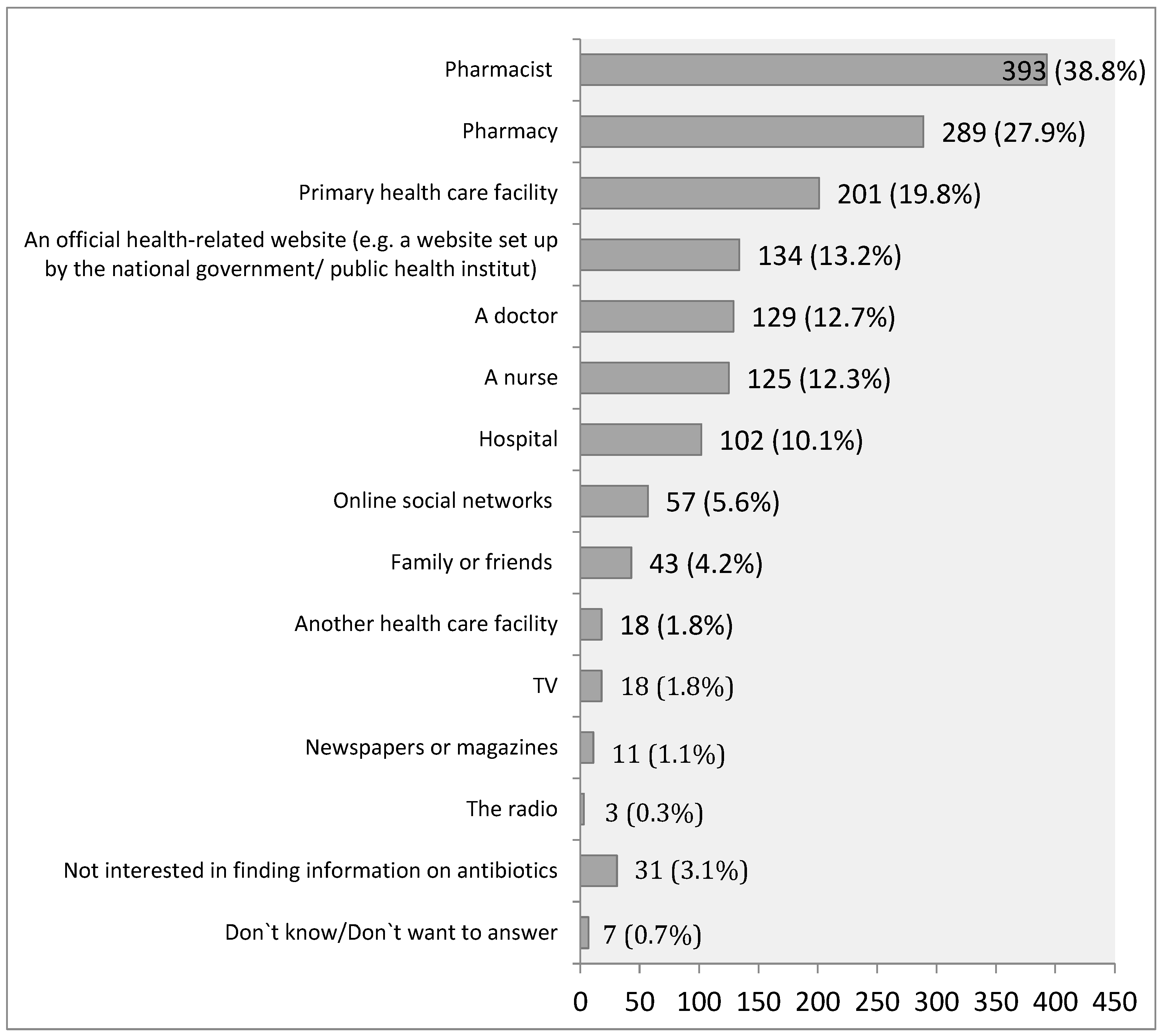

2.1.3. Attitudes About Trustworthy Sources of Information About Antibiotics

2.1.4. Attitudes About the Antibiotics Use in Farm Animals

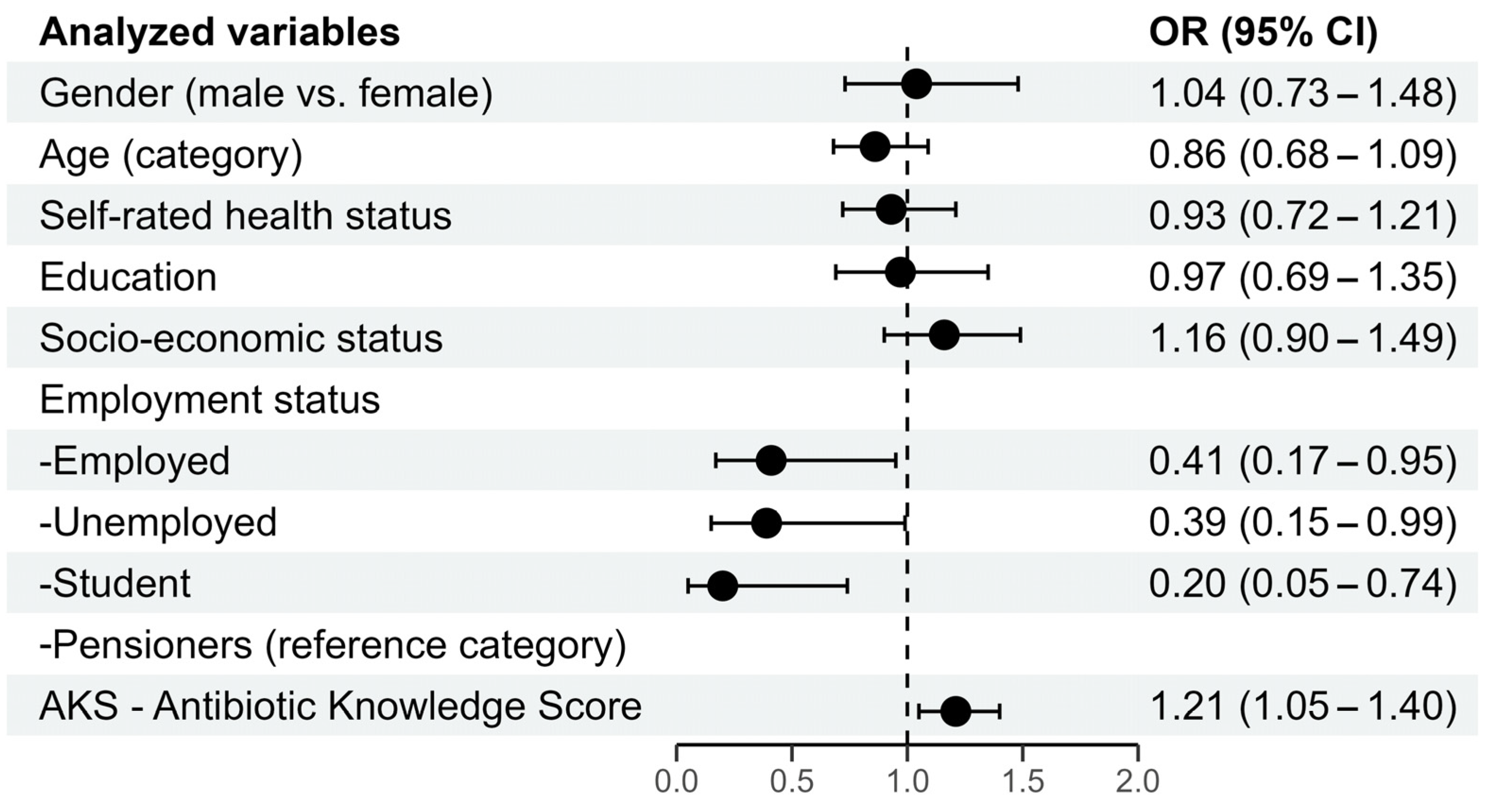

2.2. Predictors of the Desirable Behavior Related to Antibiotic Use

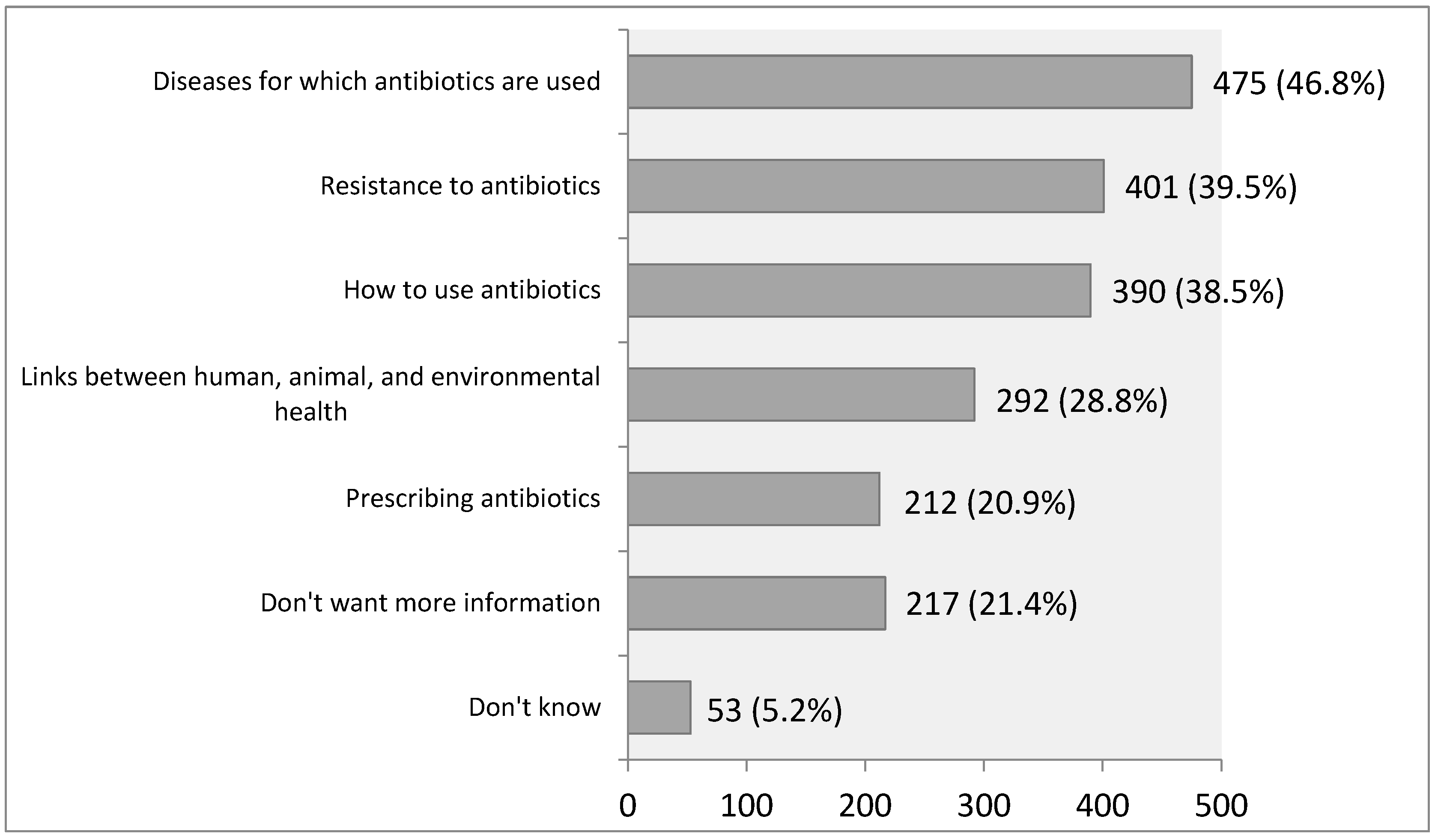

2.3. Interest in Different Topics About Antibiotic Use

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Statistical Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AKS | Antibiotic Knowledge Score |

| EU | European Union |

| KAP | Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Studies |

| POCIs | Point-of-Care Interventions |

References

- Serna, C.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B. Antimicrobial resistance and One Health. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2022, 35 (Suppl. 3), 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samreen Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: A potential threat to public health. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J. Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO One Health. A One Health Priority Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, United Nations Environment Programme and World Organisation for Animal Health: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/one-health (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Caneschi, A.; Bardhi, A.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A. The Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Veterinary Medicine, a Complex Phenomenon: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shryock, T.R.; Richwine, A. The interface between veterinary and human antibiotic use. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1213, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T.M. Use of antimicrobial agents in veterinary medicine and implications for human health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 31, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjegovic-Mikanovic, V.; Vasic, M.; Vukovic, D.; Jankovic, J.; Jovic-Vranes, A.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Hernández-Quevedo, C. Serbia: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2019, 21, i–211. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E. Health Systems in Action (HSiA) Insights—Serbia 2024; European Observatory on Health Systems Policies WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vojvodic, K.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Wolf, G.W. Socio-Economic Inequalities, Out-of-Pocket Payment and Consumers’ Satisfaction with Primary Health Care: Data from the National Adult Consumers’ Satisfaction Survey in Serbia 2009–2015. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Antibiotic Resistance Control Programme for the Period 2019–2021. Republic of Serbia. 2019. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/amr-spc-npm/nap-library/serbia_national-antibiotic-resistance-control-programme-2019-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=7e2eb9c0_1&download=true (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bright-Ponte, S.J.; Walters, B.K.; Tate, H.; Durso, L.; Whichard, J.; Bjork, K.; Shivley, C.; Beaudoin, A.; Cook, K.; Thacker, E.; et al. One Health and antimicrobial resistance, a United States perspective. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2019, 38, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, J.; Stojanović, D.; Cagnardi, P.; Kladar, N.; Horvat, O.; Ćirković, I.; Bijelić, K.; Stojanac, N.; Kovačević, Z. Farm Animal Veterinarians’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use in the Republic of Serbia. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belamarić, G.; Bukumirić, Z.; Vuković, M.; Spaho, R.S.; Marković, M.; Marković, G.; Vuković, D. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding antibiotic use among the population of the Republic of Serbia—A cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16 (Suppl. S1), 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Special Eurobarometer 478: Antimicrobial Resistance (in the EU), Report 2018-11–13. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2190_90_1_478_eng?locale=en (accessed on 19 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Gili, R.; Scaioli, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. General population’s knowledge and attitudes about antibiotics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2015, 24, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, O.; Scott, A.M.; Montgomery, A.; Nicholas, B.; Mullan, J.; van Oijen, A.; Degeling, C. Comparing public attitudes, knowledge, beliefs and behaviours towards antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in Australia, United Kingdom, and Sweden (2010–2021): A systematic review, meta-analysis, and comparative policy analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuniawati, H.; Hassali, M.A.A.; Suryawati, S.; Ismail, W.I.; Taufik, T.; Hossain, M.S. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Antibiotic Use among the Population of Boyolali, Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Lerche, C.J.; Thomsen, K.; Hartvig, T.; Schierbeck, J.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Ciofu, O.; Høiby, N. Antibiotic therapy as personalized medicine-general considerations and complicating factors. APMIS 2019, 127, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasala, A.; Hytönen, V.P.; Laitinen, O.H. Modern Tools for Rapid Diagnostics of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’hulster, E.; De Burghgraeve, T.; Luyten, J.; Verbakel, J.Y. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care interventions to tackle inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in high- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, S.; Jansen, D.E.M.C.; van der Velden, A.W.; Butler, C.C.; Verheij, T.J.M.; Friedrich, A.W.; Postma, M.J.; van Asselt, A.D.I. The Opportunity of Point-of-Care Diagnostics in General Practice: Modelling the Effects on Antimicrobial Resistance. PharmacoEconomics 2022, 40, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.B.; Wei, W.Q.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M.E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K.; Zhao, J.; Snowdon, J.L. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, M.R.; Ifteakhar, K.M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Sakib, Q.N. Public knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) regarding antibiotics use and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phagava, H.; Balamtsarashvili, T.; Pagava, K.; Mchedlishvili, I. Survey of practices, knowledge and attitude concerning antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance among medical university students. Georgian Med. News 2019, 294, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Hayat, K.; Shi, L.; Lambojon, K.; Saeed, A.; Aziz, M.M.; Liu, T.; Ji, S.; Gong, Y.; Feng, Z.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Among Chinese Pharmacy Customers: A Multicenter Survey Study. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölstad, S.; Löfmark, S.; Carlin, K.; Erntell, M.; Aspevall, O.; Blad, L.; Hanberger, H.; Hedin, K.; Hellman, J.; Norman, C.; et al. Lessons learnt during 20 years of the Swedish strategic programme against antibiotic resistance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avent, M.L.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Price-Haywood, E.G.; van Driel, M.L. Antimicrobial stewardship in the primary care setting: From dream to reality? BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, A.P.; Malabar, L.; McCabe, P.G.; Gitsham, A.; Jarman, I. Antibiotic prescribing trends in primary care 2014-2022. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.; Alo, M.; Hossain, M.F.; Emran, T.B.; Uddin, M.Z.; Paul, A. Prevalence of multi-drug resistance traits in probiotic bacterial species from fermented milk products in Bangladesh. Microbiol. Res. Int. 2019, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Ranucci, E.; Romagnoli, P.; Giaccone, V. Antimicrobial resistance: A global emerging threat to public health systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2857–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, A.; Reid, S.; Assefa, Y. A review of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance: Strengths and weaknesses. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. TrACSS Country Report on the Implementation of National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)—Serbia. 2021. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/amr-spc-npm/tracss/tracss-2021-serbia.pdf?sfvrsn=294682e8_5&download=true (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Kamata, K.; Tokuda, Y.; Gu, Y.; Ohmagari, N.; Yanagihara, K. Public knowledge and perception about antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance in Japan: A national questionnaire survey in 2017. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| When Should You Stop Taking Antibiotics Once You Have Begun a Course of Treatment? | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| When I feel better | 105 | 10.4 |

| When I have taken all antibiotics as directed by my doctor | 868 | 85.6 |

| Other reasons | 27 | 2.7 |

| I don’t know | 14 | 1.4 |

| Use of Antibiotics in Animals | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| To what extent do you agree or disagree that sick farm animals, i.e., animals used for consumption (meat, dairy products, etc.), should be treated with antibiotics if this is the most appropriate treatment? | Totally agree | 194 | 19.1 |

| Tend to agree | 303 | 29.9 | |

| Tend to disagree | 114 | 11.2 | |

| Totally disagree | 176 | 17.4 | |

| Don’t know | 227 | 22.4 | |

| Did you know that using antibiotics to stimulate growth in farm animals is banned within the EU? | Yes | 382 | 37.3 |

| No | 632 | 62.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belamarić, G.; Vuković, D.; Bukumirić, Z.; Sandić Spaho, R.; Marković, G. Public Awareness and Perceptions of Antibiotic Use in Human and Veterinary Medicine in Serbia. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050523

Belamarić G, Vuković D, Bukumirić Z, Sandić Spaho R, Marković G. Public Awareness and Perceptions of Antibiotic Use in Human and Veterinary Medicine in Serbia. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(5):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050523

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelamarić, Gordana, Dejana Vuković, Zoran Bukumirić, Rada Sandić Spaho, and Gordana Marković. 2025. "Public Awareness and Perceptions of Antibiotic Use in Human and Veterinary Medicine in Serbia" Antibiotics 14, no. 5: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050523

APA StyleBelamarić, G., Vuković, D., Bukumirić, Z., Sandić Spaho, R., & Marković, G. (2025). Public Awareness and Perceptions of Antibiotic Use in Human and Veterinary Medicine in Serbia. Antibiotics, 14(5), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14050523