In Vitro Evaluation of Fosfomycin Combinations Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Bacterial Isolates’ Characteristics

2.2. Synergistic Activity of FOS Combinations Using Agar Dilution Checkerboard Assays

2.3. Directionality of FOS and CAZ-AVI Antibiotic Interaction

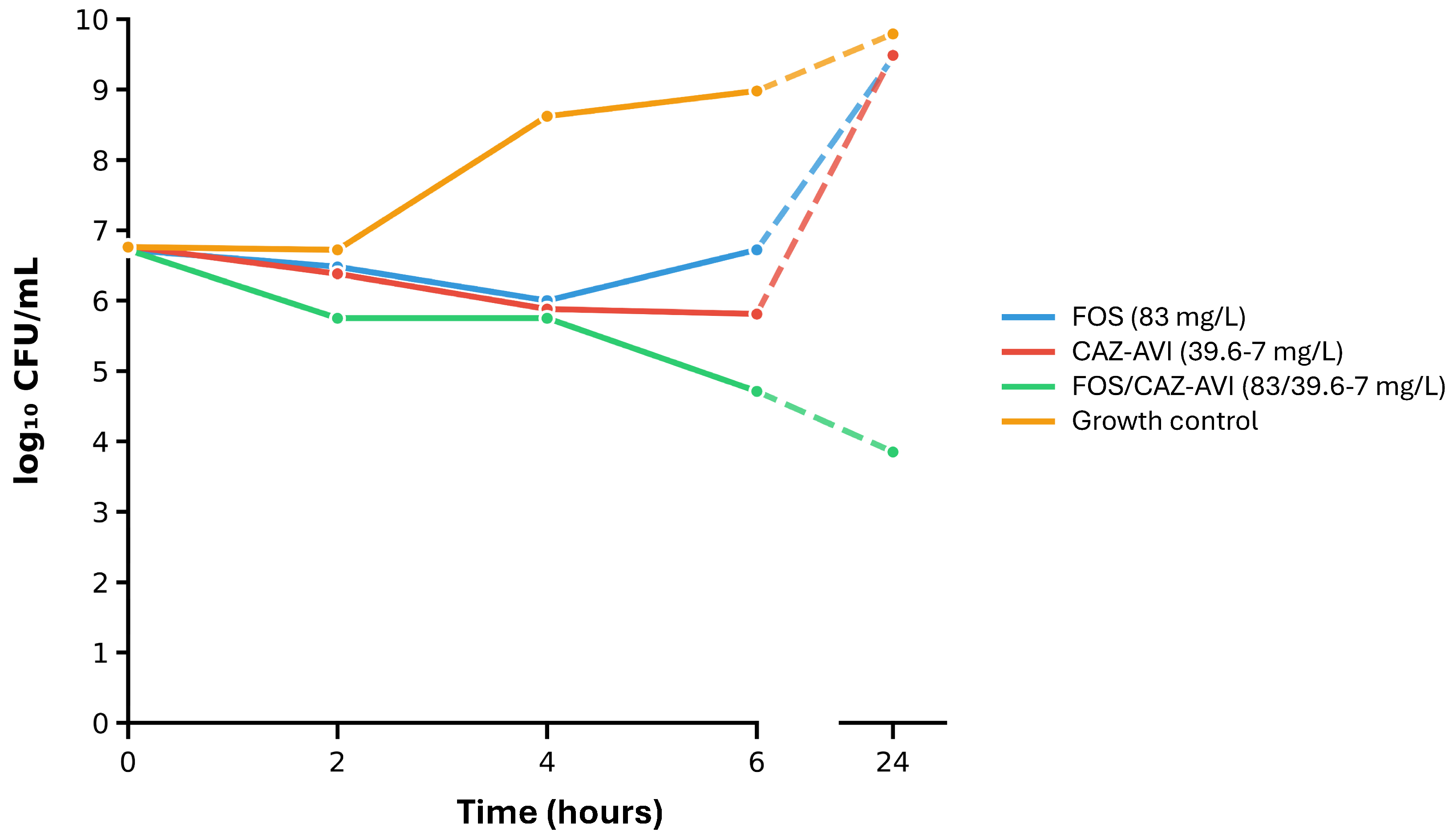

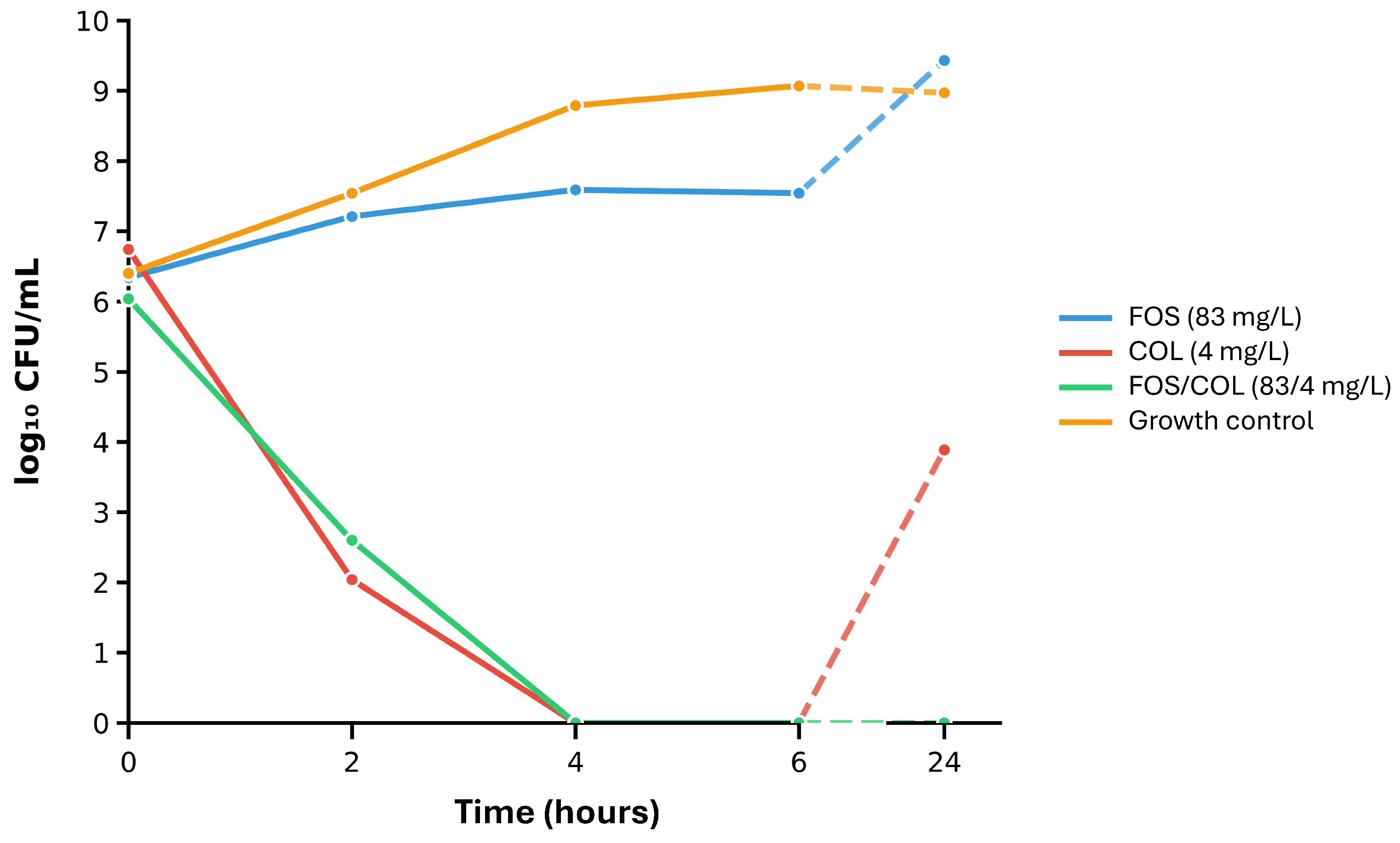

2.4. Time-Kill Assays on Selected Isolates and the Most Synergistic Antimicrobial Combinations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.3. Evaluation of Combined Antimicrobial Activity

4.3.1. Agar Dilution Checkerboard Testing

4.3.2. Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) Calculation

4.3.3. Directionality of Antimicrobial Combination Effects

4.3.4. Susceptibility Breakpoint Index (SBPI) Evaluation

4.3.5. Time-Kill Assays

4.4. Data Analysis and Software

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | Amikacin |

| AZT | Aztreonam |

| AZT-AVI | Aztreonam–avibactam |

| BLBLI | β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| COL | Colistin |

| CTX-M | Cefotaximase Munich |

| CAZ-AVI | Ceftazidime–avibactam |

| ECOFF | Epidemiological cut-off |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| FDC | Cefiderocol |

| FIC | Fractional inhibitory concentration |

| FICI | Fractional inhibitory concentration index |

| FOS | Fosfomycin |

| GIM | German imipenemase |

| IMP | Imipenemase |

| KPC | Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight |

| MBL | Metallo-β-lactamase |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| MER | Meropenem |

| MHT | Modified Hodge test |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase |

| OXA | Oxacillinase |

| PBA | Phenylboronic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| SBPI | Susceptible breakpoint index |

| TEM | Temoneira β-lactamase |

| VIM | Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

References

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; the GBD 2021 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240116337 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Boyd, S.E.; Livermore, D.M.; Hooper, D.C.; Hope, W.W. Metallo-β-Lactamases: Structure, Function, Epidemiology, Treatment Options, and the Development Pipeline. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, M.F.; Rossi, M.-A.; Vila, A.J.; Bonomo, R.A. The Urgent Need for Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitors: An Unattended Global Threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e28–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, H.G.; Perera, S.R.; Tremblay, Y.D.; Thomassin, J.-L. Antimicrobial Resistance in Klebsiella Pneumoniae: An Overview of Common Mechanisms and a Current Canadian Perspective. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024, 70, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, D.; Hou, Q.; Li, G.; Han, H. The Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance and Drug Resistance Transmission of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J. Antibiot. 2025, 78, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Saraogi, I. Navigating Antibiotic Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Current Challenges and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Chemphyschem 2025, 26, e202401057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.; Klamer, K.; Zimmerman, J.; Kale-Pradhan, P.B.; Bhargava, A. Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa in Clinical Settings: A Review of Resistance Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Pathogens 2024, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başaran, S.N.; Öksüz, L. Newly Developed Antibiotics against Multidrug-Resistant and Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Action and Resistance Mechanisms. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losito, A.R.; Raffaelli, F.; Del Giacomo, P.; Tumbarello, M. New Drugs for the Treatment of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infections with Limited Treatment Options: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabein, B.; Arhin, F.F.; Daikos, G.L.; Moore, L.S.P.; Balaji, V.; Baillon-Plot, N. Navigating the Current Treatment Landscape of Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Infections: What Are the Limitations? Infect. Dis. Ther. 2024, 13, 2423–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, P.; Khadka, C.; Shyaula, M.; Syangtan, G.; Joshi, T.P.; Pepper, S.H.; Kanel, S.R.; Pokhrel, L.R. Prevalence of Metallo-β-Lactamases as a Correlate of Multidrug Resistance among Clinical Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates in Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kontogiannis, D.S.; Ragias, D.; Kakoullis, S.A. Antibiotics for the Treatment of Patients with Metallo-β-Lactamase (MBL)-Producing Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcia-Lacalle, A.; Canut-Blasco, A.; Solinís, M.Á.; Isla, A.; Rodríguez-Gascón, A. Clinical Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Novel β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations: A Systematic Review. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Tenorio, C.; Bou, G.; Oliver, A.; Rodríguez-Aguirregabiria, M.; Salavert, M.; Martínez-Martínez, L. The Challenge of Treating Infections Caused by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Narrative Review. Drugs 2024, 84, 1519–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanj, S.S.; Kantecki, M.; Arhin, F.F.; Gheorghe, M. Epidemiology and Outcomes Associated with MBL-Producing Enterobacterales: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2025, 65, 107449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiseo, G.; Stefani, S.; Fasano, F.R.; Falcone, M. The Burden of Infections Caused by Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales in Italy: Epidemiology, Outcomes, and Management. Infez. Med. 2025, 33, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Vouloumanou, E.K.; Samonis, G.; Vardakas, K.Z. Fosfomycin. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmann, K.-F.; Hagel, S.; Oliva, A.; Kluge, S.; Mularoni, A.; Galfo, V.; Falcone, M.; Pletz, M.W.; Lindau, S.; Käding, N.; et al. Real-World Use, Effectiveness, and Safety of Intravenous Fosfomycin: The FORTRESS Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 14, 765–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putensen, C.; Ellger, B.; Sakka, S.G.; Weyland, A.; Schmidt, K.; Zoller, M.; Weiler, N.; Kindgen-Milles, D.; Jaschinski, U.; Weile, J.; et al. Current Clinical Use of Intravenous Fosfomycin in ICU Patients in Two European Countries. Infection 2019, 47, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, D.A.; Patel, N.; O’Donnell, J.N.; Lodise, T.P. Combination Therapy with IV Fosfomycin for Adult Patients with Serious Gram-Negative Infections: A Review of the Literature. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2421–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, S.; Giannitsioti, E.; Mayer, C. Emerging Concepts for the Treatment of Biofilm-Associated Bone and Joint Infections with IV Fosfomycin: A Literature Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasia, A.; Bonura, S.; Rubino, R.; Giammanco, G.M.; Miccichè, I.; Di Pace, M.R.; Colomba, C.; Cascio, A. The Use of Intravenous Fosfomycin in Clinical Practice: A 5-Year Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Hospital in Italy. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegka, K.G.; Voulgaris, G.L.; Kyriakidou, M.; Kapaskelis, A.; Falagas, M.E. Intravenous Fosfomycin for the Treatment of Patients with Bone and Joint Infections: A Review. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardakas, K.Z.; Legakis, N.J.; Triarides, N.; Falagas, M.E. Susceptibility of Contemporary Isolates to Fosfomycin: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 47, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timsit, J.-F.; Wicky, P.-H.; de Montmollin, E. Treatment of Severe Infections Due to Metallo-Betalactamases Enterobacterales in Critically Ill Patients. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnevend, Á.; Ghazawi, A.; Darwish, D.; Barathan, G.; Hashmey, R.; Ashraf, T.; Rizvi, T.A.; Pál, T. In Vitro Efficacy of Ceftazidime-Avibactam, Aztreonam-Avibactam and Other Rescue Antibiotics against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales from the Arabian Peninsula. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 99, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, L.; Likić, R.; Erdeljić, V.; Mareković, I.; Firis, N.; Grgić-Medić, M.; Godan, A.; Tomić, I.; Hunjak, B.; Markotić, A.; et al. Activity of Fosfomycin against Nosocomial Multiresistant Bacterial Pathogens from Croatia: A Multicentric Study. Croat. Med. J. 2018, 59, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Rocca, M.T.; Di Caprio, G.; Colucci, F.; Merola, F.; Panetta, V.; Cordua, E.; Greco, R. Fosfomycin-Meropenem Synergistic Combination against NDM Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains. New Microbiol. 2023, 46, 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bakthavatchalam, Y.D.; Shankar, A.; Manokaran, Y.; Walia, K.; Veeraraghavan, B. Can Fosfomycin Be an Alternative Therapy for Infections Caused by E. Coli Harbouring Dual Resistance: NDM and Four-Amino Acid Insertion in PBP3? JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, O.K.; Tufanoglu, P.; Cetinkaya, O.; Ozhak, B.; Yazisiz, H.; Ongut, G.; Turhan, O.; Ogunc, D. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol and Ceftazidime-Avibactam, Against Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. Clin. Lab. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrief, R.; El-Ashry, A.H.; Mahmoud, R.; El-Mahdy, R. Effect of Colistin, Fosfomycin and Meropenem/Vaborbactam on Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 6203–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonello, R.M.; Principe, L.; Maraolo, A.E.; Viaggi, V.; Pol, R.; Fabbiani, M.; Montagnani, F.; Lovecchio, A.; Luzzati, R.; Di Bella, S. Fosfomycin as Partner Drug for Systemic Infection Management. A Systematic Review of Its Synergistic Properties from In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipitone, G.; Di Bella, S.; Maraolo, A.E.; Granata, G.; Gatti, M.; Principe, L.; Russo, A.; Gizzi, A.; Pallone, R.; Cascio, A.; et al. Intravenous Fosfomycin for Systemic Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGowan, A.P.; Griffin, P.; Attwood, M.L.G.; Daum, A.M.; Avison, M.B.; Noel, A.R. The Pharmacodynamics of Fosfomycin in Combination with Meropenem against Klebsiella Pneumoniae Studied in an in Vitro Model of Infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, J.; Mazucheli, J.; Barros, J.P.d.R.; Szczerepa, M.M.d.A.; Nishiyama, S.A.B.; Carrara-Marroni, F.E.; Sy, S.; Fidler, M.; Sy, S.K.B.; Tognim, M.C.B. Pharmacodynamic Attainment of the Synergism of Meropenem and Fosfomycin Combination against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Producing Metallo-β-Lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00126-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tängdén, T.; Hickman, R.A.; Forsberg, P.; Lagerbäck, P.; Giske, C.G.; Cars, O. Evaluation of Double- and Triple-Antibiotic Combinations for VIM- and NDM-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae by in Vitro Time-Kill Experiments. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturk Sengel, B.; Altinkanat Gelmez, G.; Soyletir, G.; Korten, V. In Vitro Synergistic Activity of Fosfomycin in Combination with Meropenem, Amikacin and Colistin against OXA-48 and/or NDM-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J. Chemother. 2020, 32, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, S.; Davis, H.; Ashcraft, D.S.; Pankey, G.A. Evaluation of the in Vitro Interaction of Fosfomycin and Meropenem against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Using Etest and Time-Kill Assay. J. Investig. Med. 2021, 69, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojdana, D.; Gutowska, A.; Sacha, P.; Majewski, P.; Wieczorek, P.; Tryniszewska, E. Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Alone and in Combination with Ertapenem, Fosfomycin, and Tigecycline Against Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, L.M.; Sutherland, C.A.; Nicolau, D.P. In Vitro Investigation of Synergy among Fosfomycin and Parenteral Antimicrobials against Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 95, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, A.T.; Ezure, Y.; Horcajada, J.P.; Harris, P.N.A.; Paterson, D.L. In Vitro, in Vivo and Clinical Studies Comparing the Efficacy of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Monotherapy with Ceftazidime-Avibactam-Containing Combination Regimens against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates or Infections: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1249030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berçot, B.; Poirel, L.; Dortet, L.; Nordmann, P. In Vitro Evaluation of Antibiotic Synergy for NDM-1-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 2295–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Tiseo, G.; Bassoulis, D.; Giordano, C.; Galfo, V.; Leonildi, A.; Tagliaferri, E.; Barnini, S.; Sani, S.; et al. Efficacy of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Plus Aztreonam in Patients With Bloodstream Infections Caused by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagvekar, V.; Shah, A.; Unadkat, V.P.; Chavan, A.; Kohli, R.; Hodgar, S.; Ashpalia, A.; Patil, N.; Kamble, R. Clinical Outcome of Patients on Ceftazidime-Avibactam and Combination Therapy in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 25, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Giordano, C.; Leonildi, A.; Galfo, V.; Lepore, A.; Suardi, L.R.; Riccardi, N.; Barnini, S.; Tiseo, G. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Infections Caused by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales: A 3-Year Prospective Study From an Endemic Area. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G. Fosfomycin as a Potential Therapeutic Option in Nonsevere Infections Caused by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales: Need for Evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Y.; Cisneros, J.M.; Paul, M.; Daikos, G.L.; Wang, M.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Singer, G.; Titov, I.; Gumenchuk, I.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Aztreonam-Avibactam versus Meropenem for the Treatment of Serious Infections Caused by Gram-Negative Bacteria (REVISIT): A Descriptive, Multinational, Open-Label, Phase 3, Randomised Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikos, G.L.; Cisneros, J.M.; Carmeli, Y.; Wang, M.; Leong, C.L.; Pontikis, K.; Anderzhanova, A.; Florescu, S.; Kozlov, R.; Rodriguez-Noriega, E.; et al. Aztreonam-Avibactam for the Treatment of Serious Infections Caused by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Pathogens: A Phase 3 Randomized Trial (ASSEMBLE). JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, M.; Aubin, G.; Caron, F.; Cattoir, V.; Dortet, L.; Goutelle, S.; Jeannot, K.; Lepeule, R.; Lina, G.; Marchandin, H.; et al. Comité de l’antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie—Recommandations Juin 2024 V.1.0. SFM/EUCAST. 2024. Available online: https://www.sfm-microbiologie.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CASFM2024_V1.0.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Li, J.; Lovern, M.; Green, M.L.; Chiu, J.; Zhou, D.; Comisar, C.; Xiong, Y.; Hing, J.; MacPherson, M.; Wright, J.G.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Pharmacodynamic Target Attainment Across Adult Indications and Patient Subgroups. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2019, 12, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, Ö.; Şahin, E.Ö.; Ayhancı, T.; Ormanoğlu, G.; Aydemir, Y.; Köroğlu, M.; Altındiş, M. Investigation of In-Vitro Efficacy of Intravenous Fosfomycin in Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates and Effect of Glucose 6-Phosphate on Sensitivity Results. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 59, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltas, I.; Patel, T.; Soares, A.L. Resistance Profiles of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales in a Large Centre in England: Are We Already Losing Cefiderocol? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Y.C.; Lobato, A.R.F.; Quaresma, A.J.P.G.; Guerra, L.M.G.D.; Brasiliense, D.M. The Spread of NDM-1 and NDM-7-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Is Driven by Multiclonal Expansion of High-Risk Clones in Healthcare Institutions in the State of Pará, Brazilian Amazon Region. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, Y.; Eto, M.; Mano, Y.; Tateda, K.; Yamaguchi, K. In Vitro Potentiation of Carbapenems with ME1071, a Novel Metallo-Beta-Lactamase Inhibitor, against Metallo-Beta-Lactamase- Producing Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3625–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzemen, N.Ü.; Önal, U.; Merdan, O.; Akca, B.; Ener, B.; Özakın, C.; Akalın, H. Synergistic Antibacterial Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam in Combination with Colistin, Gentamicin, Amikacin, and Fosfomycin against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, P.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Effect of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Combined with Different Antimicrobials against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00107-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, C.; Maraolo, A.E.; Di Bella, S.; Luzzaro, F.; Principe, L. The Revival of Aztreonam in Combination with Avibactam against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negatives: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies and Clinical Cases. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; de Jonge, B.L.M.; Stone, G.G.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime/Avibactam against Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Collected in European Countries: INFORM Global Surveillance 2012–15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2777–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samonis, G.; Maraki, S.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Vouloumanou, E.K.; Falagas, M.E. Synergy of Fosfomycin with Carbapenems, Colistin, Netilmicin, and Tigecycline against Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Escherichia Coli, and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Ni, W.; Wang, J.; Liang, B.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y. In Vitro Activity of Fosfomycin in Combination with Colistin against Clinical Isolates of Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomas Aeruginosa. J. Antibiot 2015, 68, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, S.; Singh, N.B.; Kebriaei, R.; Rice, S.A.; Stamper, K.C.; Castanheira, M.; Rybak, M.J. Evaluation of the Synergy of Ceftazidime-Avibactam in Combination with Meropenem, Amikacin, Aztreonam, Colistin, or Fosfomycin against Well-Characterized Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanelli, F.; De Robertis, A.; Carone, G.; Dalfino, L.; Stufano, M.; Del Prete, R.; Mosca, A. In Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime/Avibactam Alone and in Combination With Fosfomycin and Carbapenems Against KPC-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. New Microbiol. 2020, 43, 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.J.; Delgado, N.N.; Maharjan, R.; Cain, A.K. How Antibiotics Work Together: Molecular Mechanisms behind Combination Therapy. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 57, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, N.; Sánchez-Hevia, D.L.; Andersson, D.I. Beyond the FIC Index: The Extended Information from Fractional Inhibitory Concentrations (FICs). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2394–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maryam, L.; Khan, A.U. A Mechanism of Synergistic Effect of Streptomycin and Cefotaxime on CTX-M-15 Type β-Lactamase Producing Strain of E. Cloacae: A First Report. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotz, P.H.; Davis, B.D. Synergism between Streptomycin and Penicillin: A Proposed Mechanism. Science 1962, 135, 1067–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Martens, M.; Kroemer, N.; Pfaffendorf, C.; Decousser, J.-W.; Nordmann, P.; Wicha, S.G. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Meropenem and Fosfomycin Combinations in in Vitro Time-Kill and Hollow-Fibre Infection Models against Multidrug-Resistant and Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamm, R.K.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Lindley, J.M.; Sweeney, K.; Ellis-Grosse, E.J.; Shortridge, D. Evaluation of the Bactericidal Activity of Fosfomycin in Combination with Selected Antimicrobial Comparison Agents Tested against Gram-Negative Bacterial Strains by Using Time-Kill Curves. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02549-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirley, M. Ceftazidime-Avibactam: A Review in the Treatment of Serious Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Drugs 2018, 78, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girlich, D.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Value of the Modified Hodge Test for Detection of Emerging Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakris, A.; Poulou, A.; Pournaras, S.; Voulgari, E.; Vrioni, G.; Themeli-Digalaki, K.; Petropoulou, D.; Sofianou, D. A Simple Phenotypic Method for the Differentiation of Metallo-Beta-Lactamases and Class A KPC Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lim, Y.S.; Yong, D.; Yum, J.H.; Chong, Y. Evaluation of the Hodge Test and the Imipenem-EDTA Double-Disk Synergy Test for Differentiating Metallo-Beta-Lactamase-Producing Isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4623–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—34th Edition, Supplement M100. Available online: https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m100/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Poulou, A.; Grivakou, E.; Vrioni, G.; Koumaki, V.; Pittaras, T.; Pournaras, S.; Tsakris, A. Modified CLSI Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) Confirmatory Test for Phenotypic Detection of ESBLs among Enterobacteriaceae Producing Various β-Lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drieux, L.; Brossier, F.; Sougakoff, W.; Jarlier, V. Phenotypic Detection of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Production in Enterobacteriaceae: Review and Bench Guide. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashti, A.; Abdulsamad, A.; Jadaon, M. Heat Treatment of Bacteria: A Simple Method of DNA Extraction for Molecular Techniques. Kuwait Med. J. 2009, 41, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lomaestro, B.M.; Tobin, E.H.; Shang, W.; Gootz, T. The Spread of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. Pneumoniae to Upstate New York. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, e26–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Poirel, L.; Naas, T.; Nicolas, D.; Collet, L.; Bellais, S.; Cavallo, J.D.; Nordmann, P. Characterization of VIM-2, a Carbapenem-Hydrolyzing Metallo-Beta-Lactamase and Its Plasmid- and Integron-Borne Gene from a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolate in France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, V.; Rai, S.; Gupta, S.; Rautela, R.S.; Chopra, R.; Rawat, D.S.; Verma, N.; Singh, N.P.; Kaur, I.R.; Bhalla, P. Development of TaqMan Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Detection of the Newly Emerging Form of Carbapenem Resistance Gene in Clinical Isolates of Escherichia Coli, Klebsiella Pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter Baumannii. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 29, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Izdebski, R.; Baraniak, A.; Fiett, J.; Herda, M.; Hrabák, J.; Derde, L.P.G.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Carmeli, Y.; Goossens, H.; et al. Survey of Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Colonizing Patients in European ICUs and Rehabilitation Units, 2008–2011. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelepi, E.; Magana, C.; Platsouka, E.; Sofianou, D.; Paniara, O.; Legakis, N.J.; Vatopoulos, A.C.; Tzouvelekis, L.S. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Types in Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Escherichia Coli in Two Greek Hospitals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 21, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myari, A.; Bozidis, P.; Priavali, E.; Kapsali, E.; Koulouras, V.; Vrioni, G.; Gartzonika, K. Molecular and Epidemiological Analysis of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae in a Greek Tertiary Hospital: A Retrospective Study. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Susceptibility Testing of Infectious Agents and Evaluation of Performance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Devices—Part 1: Broth Micro-Dilution Reference Method for Testing the in Vitro Activity of Antimicrobial Agents against Rapidly Growing Aerobic Bacteria Involved in Infectious Diseases (ISO 20776-1:2019). Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70464.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Dilution of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—10th Edition. CLSI Document M07-A10. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1954721 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Disk Diffusion Methodology (Manual Version 13.0). Available online: https://www.eucast.org/ast_of_bacteria/disk_diffusion_methodology (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Qi, C.; Xu, S.; Wu, M.; Zhu, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Huang, X. Pharmacodynamics of Linezolid-Plus-Fosfomycin Against Vancomycin-Susceptible and Resistant Enterococci In Vitro and In Vivo of a Galleria Mellonella Larval Infection Model. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3497–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müderris, T.; Dursun Manyaslı, G.; Sezak, N.; Kaya, S.; Demirdal, T.; Gül Yurtsever, S. In-Vitro Evaluation of Different Antimicrobial Combinations with and without Colistin against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii Clinical Isolates. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, K.E.N.; Gould, I.M. Combination Testing of Multidrug-Resistant Cystic Fibrosis Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Use of a New Parameter, the Susceptible Breakpoint Index. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Clinical Breakpoints and Dosing of Antibiotics (Table Version 15.0). Available online: https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Nussbaumer-Pröll, A.; Obermüller, M.; Weiss-Tessbach, M.; Eberl, S.; Zeitlinger, M.; Matiba, B.; Mayer, C.; Kussmann, M. Synergistic Activity of Fosfomycin and Flucloxacillin against Methicillin-Susceptible and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus: In Vitro and in Vivo Assessment. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 214, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossum, G.V.; Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual: (Python Documentation Manual Part 2); CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, South Carolina, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4414-1269-0. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing—The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

| MIC [mg/L] | EUCAST Breakpoints | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC Range | MIC Breakpoint [mg/L] | S [%] | R [%] |

| K. pneumoniae (n = 22) | ||||||

| FOS a | 32 | 1024 | 1–1024 | ≤128 c | 81.8 * | 18.2 * |

| AMI | 16 | 256 | 1–256 | ≤(8) d | 31.8 | 68.2 |

| MER | 64 | 64 | 0.5–64 | ≤8 e | 13.6 | 86.4 |

| COL | 0.5 | 64 | 0.5–64 | ≤(2) d | 72.7 | 27.3 |

| CAZ-AVI | 1024 | 1024 | 1–1024 | ≤8 | 9.1 | 90.9 |

| AZT-AVI | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.06–1 | ≤4 | 100 | 0 |

| FDC b | 1 | 16 | 0.06–32 | ≤2 | 54.5 | 45.5 |

| P. aeruginosa (n = 20) | ||||||

| FOS a | 16 | 128 | 4–1024 | ≤256 c | 90.0 ** | 10.0 ** |

| MER | 64 | 64 | 0.5–64 | ≤8 e | 15.0 | 85.0 |

| COL | 1 | 4 | 1–16 | ≤(4) d | 95.0 | 5.0 |

| AZT | 16 | 32 | 4–128 | ≤16 e | 60.0 | 40.0 |

| CAZ-AVI | 128 | 1024 | 1–1024 | ≤8 | 15.0 | 85.0 |

| AZT-AVI | 16 | 32 | 0.06–64 | IE | - | - |

| FDC b | 0.5 | 4 | 0.06–4 | ≤2 | 80.0 | 20.0 |

| Combination | FICI Category (n [%]) * | MIC Fold-Reduction (FOS/Partner) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synergy | Additivity | Indifference | Antagonism | ||

| K. pneumoniae (n = 22) | |||||

| FOS+MER a | 7 (31.8) | 7 (31.8) | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 0–128/0–128 |

| FOS+COL a | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 19 (86.4) | 0 (0) | 0–512/0–16 |

| FOS+AMI a | 3 (13.6) | 8 (36.4) | 11 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0–32/0–32 |

| FOS+CAZ-AVI a | 16 (72.7) | 1 (4.5) | 4 (18.2) | 1 (4.5) | 0–2048/8–1024 |

| FOS+FDC a | 7 (31.8) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (45.5) | 0 (0) | 0–64/0–16 |

| FOS+AZT-AVI a | 7 (31.8) | 5 (22.7) | 10 (45.5) | 0 (0) | 0–2133/0–16 |

| P. aeruginosa (n = 20) | |||||

| FOS+MER b | 6 (30.0) | 6 (30.0) | 8 (40.0) | 0 (0) | 0–8/0–16 |

| FOS+COL b | 13 (65.0) | 5 (25.0) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 0–256/0–32 |

| FOS+AZT b | 3 (15.0) | 8 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) | 0 (0) | 0–8/0–32 |

| FOS+CAZ-AVI b | 8 (40.0) | 7 (35.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0–2/0–1024 |

| FOS+FDC b | 1 (5.0) | 9 (45.0) | 9 (45.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0–512/0–4 |

| FOS+AZT-AVI b | 11 (55.0) | 6 (30.0) | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0) | 0–8/0–32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wohlfarth, E.; Dinh, A.; Vrioni, G.; Żabicka, D.; Bernardo, M.; Tascini, C.; Noussair, L.; Mayer, C. In Vitro Evaluation of Fosfomycin Combinations Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121247

Wohlfarth E, Dinh A, Vrioni G, Żabicka D, Bernardo M, Tascini C, Noussair L, Mayer C. In Vitro Evaluation of Fosfomycin Combinations Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121247

Chicago/Turabian StyleWohlfarth, Esther, Aurélien Dinh, Georgia Vrioni, Dorota Żabicka, Mariano Bernardo, Carlo Tascini, Latifa Noussair, and Christian Mayer. 2025. "In Vitro Evaluation of Fosfomycin Combinations Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121247

APA StyleWohlfarth, E., Dinh, A., Vrioni, G., Żabicka, D., Bernardo, M., Tascini, C., Noussair, L., & Mayer, C. (2025). In Vitro Evaluation of Fosfomycin Combinations Against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121247