5. Coumarin Hybrid Compounds with Antimicrobial Activity

Globally, fungal infections are causing a strain on public health systems, as more cases and fatalities are being reported [

43,

44]. This is due to the limited class of both synthetic and natural antifungal drugs (depicted in

Figure 4) available on the market, contributing to the increasing number of fungal infection casualties, as fungal pathogens such as

Candida,

Aspergillus, and

Cryptococcus genera develop defensive mechanisms against these antifungal drugs [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Additionally, narrow therapeutic indices and poor oral bioavailability also hamper the efficacy of the currently used drugs [

43].

On the one hand, bacterial infections also contribute to the increasing number of deaths, cases, and hospitalizations, due to the failure of the currently employed therapeutic agents [

47,

48]. Antibiotic resistance is a major contributor to the failure of the commercially available drugs, and this has become a concern for medicinal scientists, who are seeking an alternative approach to overcome the challenges associated with currently used drugs [

49,

50,

51]. Hybridization is among the most beneficial structural modification strategies gaining momentum in the drug discovery industry [

49]. The drugs developed using this approach displayed a series of advantages, including reduced drug–drug interactions, improved pharmacokinetic properties, reduced toxicity, and improved patient compliance [

50,

51]. Hence, scientists are hybridizing different pharmacophores with coumarin, resulting in new antimicrobial agents with enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

The use of the heterocyclic compound to develop new compounds has gained momentum. Thus, Abbas et al. [

52] reported that 60% of the most successful pharmaceuticals available on the market contain heterocyclic scaffolds. Hence, coumarins are combined with other scaffolds to develop drugs for microbial infections. Farhan and co-partners synthesized new antimicrobial agents via a combination of 4-thiazolidinone and a coumarin scaffold [

53]. The naturally occurring scaffold (coumarin) and the bioactive motif (4-thiazolidinone) are showered with several biological applications, and they possess antifungal, anticancer, antibacterial, anti-HIV, and anti-inflammatory activities, making them a powerful match to develop new hybrid compounds with antimicrobial activity [

53]. The preliminary studies against antibacterial strains and human antifungal strains showed compound

1 (displayed in

Figure 5) to be the most antimicrobial active compound compared to its counterparts. However, all the synthesized hybrids showed inferior antimicrobial properties with inhibition zones (displayed in

Table 1) between 8 and 17 mm compared to 20 and 26 mm for the reference drugs. Notably, the type of substituents on the hybrids influenced their antimicrobial effect, with the nitro group-containing hybrids exhibiting a more pronounced antimicrobial effect compared to those containing bromo, chloro, and methyl groups [

53]. Therefore, more evaluations, including clinical studies, are paramount to validate the outcomes of this study.

Abo-Salem et al. [

54] synthesized a generation of coumarin-sulfonamide hybrids through a combination of the coumarin scaffold with sulfa drugs and amino-heterocyclic compounds. The antimicrobial activity of these hybrids was evaluated in vitro against two antibacterial strains (

S. aureus and

E. coli) and human antifungal strains (

C. albicans and

A. niger) [

54]. The compounds behaved differently against antimicrobial pathogens, with hybrid

2 (depicted in

Figure 6) showing a better inhibition zone (28–39 mm) against all the antimicrobial strains, in contrast to other hybrids (0–26 mm) and neomycin (0–28 mm), as depicted in

Table 2 [

54]. This was validated by the MIC results, as this compound exhibited four-fold more antimicrobial activity with MIC values of 4.88 and 9.76 µg/mL against

S. aureus and

C. albicans, compared to 19.53 and 39.06 μg/mL of neomycin, respectively [

54]. Consequently, this hybrid depicted a greater ability to inhibit DNA gyrase compared to other tested compounds with an IC

50 value of 1.793 μg/mL, which is close to that of a well-known DNA gyrase inhibitor (novobiocin) with an IC

50 value of 1.425 µg/mL [

54].

In silico molecular docking studies revealed that compound

2 displayed a comparable binding energy with novobiocin against DNA gyrase B targets, showing interaction with DNA gyrase B amino acid residues by forming the hydrogen bond via NH, SO

2, and CO groups. It further interacted with the amino acid residues via alkyl, pi–sigma, and pi–alkyl interactions through benzene, pyrone, and cyclohexane. Hence, the SAR illustrated that the NH of the pyridine ring, C-O-C, and C-O of the pyrone ring were paramount in suppressing the DNA gyrase, leading to cell death [

54]. Moreover, the in silico ADME studies revealed that hybrid

2 showed a good bioavailability score of 0.55, water solubility (LogS = −2.56), and drug likeness with no Lipinski’s rule violation, except one minor violation of TPSA, which was greater than 140 Å

2. In essence, Hybrid

2 displayed good antimicrobial ability, and it can be recommended as a potent antimicrobial candidate among the synthesized hybrids [

54].

The pharmacological effect of two compounds of natural origin, coumarin and chalcones, including their derivatives, led to Ngaini et al. [

55] to hybridize these two scaffolds to enhance their synergistic effect. The ester-linked halogenated hybrids were synthesized and tested against two bacterial strains,

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa, in vitro. The hybridization of these two pharmacophores resulted in more antibacterial activity in hybrids in comparison to their parent compounds [

55]. Notably, the compounds exhibited marginally more antibacterial activity against

P. aeruginosa compared to

E. coli, and this was attributed to the thick bacterial cell walls and outer membrane layers of the Gram-negative

E. coli. Hence, hybrid

3a and

3b, shown in

Figure 7, were the most antibacterial effective agents with an inhibition zone (shown in

Table 3) of 12 mm and 13 mm against

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa, respectively [

55].

It was noted that the introduction of either a chloro or bromo group in the ortho position of the chalcone moiety resulted in enhanced antibacterial effect, illustrating the ortho position as an ideal site of halogenation, as they displayed good interaction and binding capability with the protein receptors [

55]. Additionally, the ester linkage also contributed to the enhanced lipophilicity, which activated the antibacterial mechanism against

P. aeruginosa, with bromine further contributing to the increased lipophilicity of the hybrids, promoting hydrophobic interactions between the cell walls of

E. coli [

55]. Therefore, in silico molecular docking studies were conducted to validate these findings. The docking results confirmed that hybrid

3a and

3b are potential antibacterial candidates with good binding interactions with protein receptors via the hydrogen bonding, aromatic, Van der Waal, and electrostatic interactions using the ketonic moiety of coumarin, the unsaturated ketonic moiety of chalcone, ortho-chlorine, and ortho-bromine with binding scores of −10.1 kcal/mol and −9.1 kcal/mol, respectively. In essence, the aromatic rings, C=O, HC=CH, and C-O, were responsible for the enhanced activity of these hybrids [

55].

Moreover, in silico ADMET predictions collaborated with the docking studies, as these two hybrids displayed good drug likeness with no violation of Lipinski’s rule and a good bioavailability score of 0.55. Additionally, the compounds displayed the ability to pass the blood–brain barrier, illustrating that they could be beneficial for the treatment of bacterial-related central nervous system disorders. Furthermore, the drugs displayed higher total clearance in the body, with compound

3a showing less toxicity. This illustrates that hybrid

3a was the most satisfactory antibacterial candidate in vitro and in silico [

55]. Therefore, more clinical trials are recommended for this hybrid.

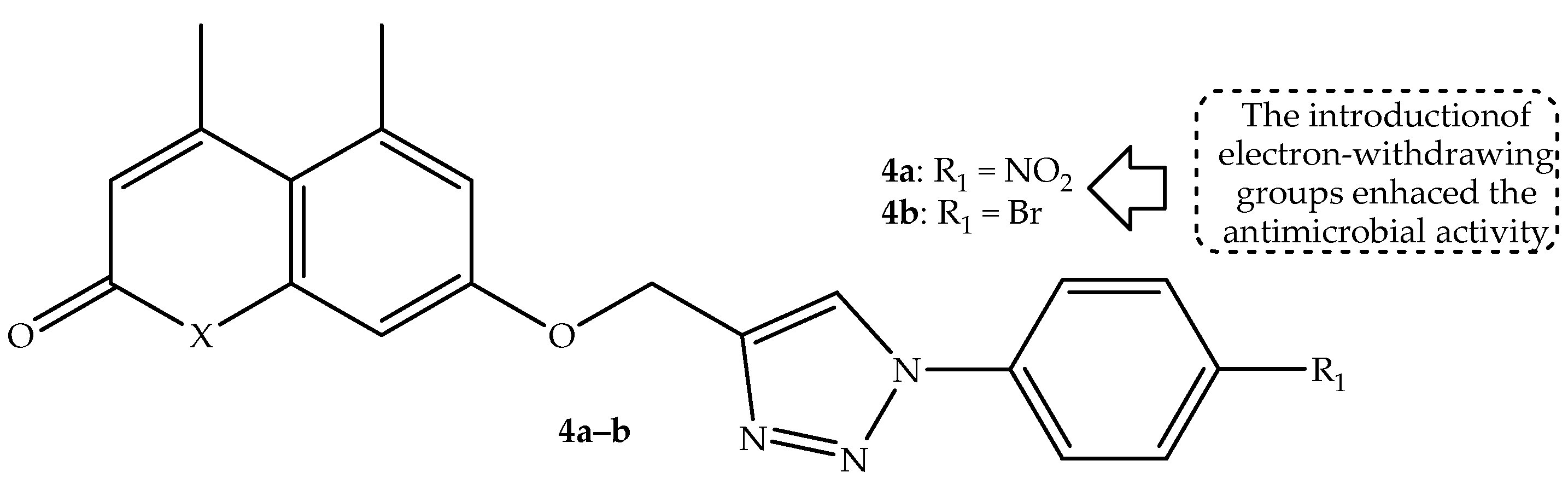

Dhawan et al. [

56] synthesized a series of 1,2,3-triazole-linked coumarin hybrids through a combination of coumarin and azide-substituted moieties via a copper-assisted 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction and evaluated their antimicrobial activity against two fungal and five bacterial strains. Hybrid

4a (displayed in

Figure 8) with a nitro group at the para-position of the aromatic ring exhibited the most antibacterial activity among the synthesized hybrids, displaying zone inhibition (displayed in

Table 4) of 14.8 mm and 15.43 mm against

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus, respectively. Furthermore, hybrid

4b (depicted in

Figure 8) displayed a better antifungal effect against

C. albicans with a zone of inhibition of 10.43 mm [

56]. Notably, the SAR highlighted that mono-substituted hybrids with the most electron-withdrawing groups exhibited better antimicrobial activity compared to those with electron-donating groups. Additionally, the alkyl chain length and aromaticity showed no significant influence on the antimicrobial activity of the hybrids. Moreover, in silico DFT predictions displayed that these hybrids are reactive and stable towards both nucleophilic and electrophilic entities [

56]. Hence, further studies are recommended to reinforce these findings.

Interestingly, Fayed et al. [

57] synthesized coumarin–chromene-based hybrid compounds via different synthetic routes and evaluated their antimicrobial activity against different bacterial and fungal strains. The hybrids behaved differently against the bacterial strains, with

5a–

c (depicted in

Figure 9) exhibiting a significant antibacterial effect, which was comparable to the reference drugs (ciprofloxacin and cephalexin), on

P. aeruginosa and

E. coli bacterial strains with MIC values (shown in

Table 5) between 0.25 and 1 μg/mL, with other synthesized hybrids displaying moderate or weak antibacterial activity with MIC values that were more than 1 μg/mL against various bacterial strains. Additionally, none of the hybrids has displayed a significant activity against the antifungal strain (

C. albicans), in vitro. Thus, the antibiofilm, DNA gyrase inhibition ability, and in silico evaluation were conducted for hybrid

5a–

c to supplement the in vitro findings.

The SAR observations demonstrated that the coumarin moiety was responsible for the potent antibacterial activity of these hybrids, with the incorporation of different substituents on the side chains of the hybrids negatively influencing the biological effect of the hybrids against the used antimicrobial strains [

57]. These three hybrids exhibited a noticeable reduction in bacterial biofilm mass compared to the positive control, novobiocin. Furthermore, among the three hybrids, compound

5a displayed a significant ability to inhibit DNA gyrase supercoiling against

E. coli genes with an IC

50 value of 5.052 μM, which was comparable to that of novobiocin (IC

50 = 3.306 μM).

This was supplemented by the docking studies, as hybrid

5a displayed a good binding energy with the DNA gyrase via hydrogen bonding with a binding score (−19.49 kcal/mol) comparable to that of novobiocin (−20.78 kcal/mol) [

57]. Hence, this hybrid was regarded as the compound that exhibited the most antibacterial activity among the synthesized hybrids. The in silico ADMET predictions confirmed this compound as a potential therapeutic candidate from the series, as it displayed no violation of drug likeness rules, a good bioavailability score (0.55), no ability to pass the BBB, and it is not a substrate of P-gp. Additionally, this hybrid showed no toxicity threats except for a compromising factor of hepatotoxicity [

57]. Therefore, more clinical trials are recommended for this drug to validate its potential as an antibacterial drug candidate.

Zeki et al. [

58] synthesize coumarin-based hybrid compounds as potential antimicrobial agents when tested against ten bacterial (four anaerobic and six aerobic Gram-negative), two fungal strains, and three normal microbiota non-pathogenic strains, with ciprofloxacin used as a reference drug. The hybrids exhibited less antibacterial activity compared to ciprofloxacin against aerobic Gram-negative bacterial strains, but better antibacterial activity compared to their parent compounds, with MBC and MIC values ranging between 2 and 29 μg/mL and 2 to 16 μg/mL, respectively [

58]. Hybrid

6a–

b (shown in

Figure 10) with a methoxy and chloro group at the para-position of the phenyl ring, displayed better antibacterial activity against selected bacterial strains compared to their counterparts, as observed on MIC values displayed in

Table 6. The SAR showed that the increasing hydrophobic nature of these hybrids influenced their antibacterial activity [

58]. Additionally, it was highlighted that increasing the hydrophilic and lipophilic nature of the hybrids, as was the case in compound

6b, results in a better antibacterial effect, as this improves the ability of a drug to break down the bacterial cell walls. Moreover, the presence of the dioxathiole ring contributed to the improvement of the antibacterial activity of the hybrids [

58]. However, a hydrophilic functional group (carboxylic group) in hybrid

6c compromised the antibacterial activity of that compound. This demonstrates the significance of the phenyl ring in the improved antibacterial effect of these hybrids [

58].

Furthermore, three hybrids,

6b–

d (depicted in

Figure 10), showed significant results against the fungal strains (

C. albicans and

A. niger), with superior MFC and MIC values between 1.30 and 2.50 µg/mL and 1.15–1.80 µg/mL, compared to 6–12 µg/mL and 4–8 µg/mL of the reference drug (nystatin), respectively [

58]. The antifungal results highlighted the importance of the dioxathiole ring in enhancing the antimicrobial effect of these hybrids. Additionally, varied substituents at the para-position of the phenyl ring influenced the antifungal activity of the hybrid in this hierarchy: COOH <

p-phenyl-F <

p-phenyl-Cl <

p-phenyl-OCH

3 <

p-phenyl-CH

3 <

p-phenyl-Br <

p-phenyl-I. The hybrids showed promising results against the normal strains, with compound

6b displaying remarkable results against

E. coli non-pathogenic strains in vitro. This illustrates that hybrid

6b can be a potential candidate to treat microbial infections [

58].

The in silico findings displayed the hybrids as good drug candidates. Specifically, they showed P-gp inhibition ability, which is a good feature for improving drug bioavailability. However, its inhibition could result in the development of interactions [

58]. Hence, hybrid

6c (P-gp non-substrate) could be recommended instead of hybrid

6a (P-gp substrate). Moreover, the drugs displayed no violation of Lipinski’s rule, showing a good drug likeness and promoting oral administration, and the hybrids cannot pass the BBB, displaying no toxic threats to the CNS. In essence, the findings demonstrate that dioxathiole ring-containing coumarin hybrids

6b and

6c could be potential antimicrobial agents [

58]. Hence, more clinical trials are recommended.

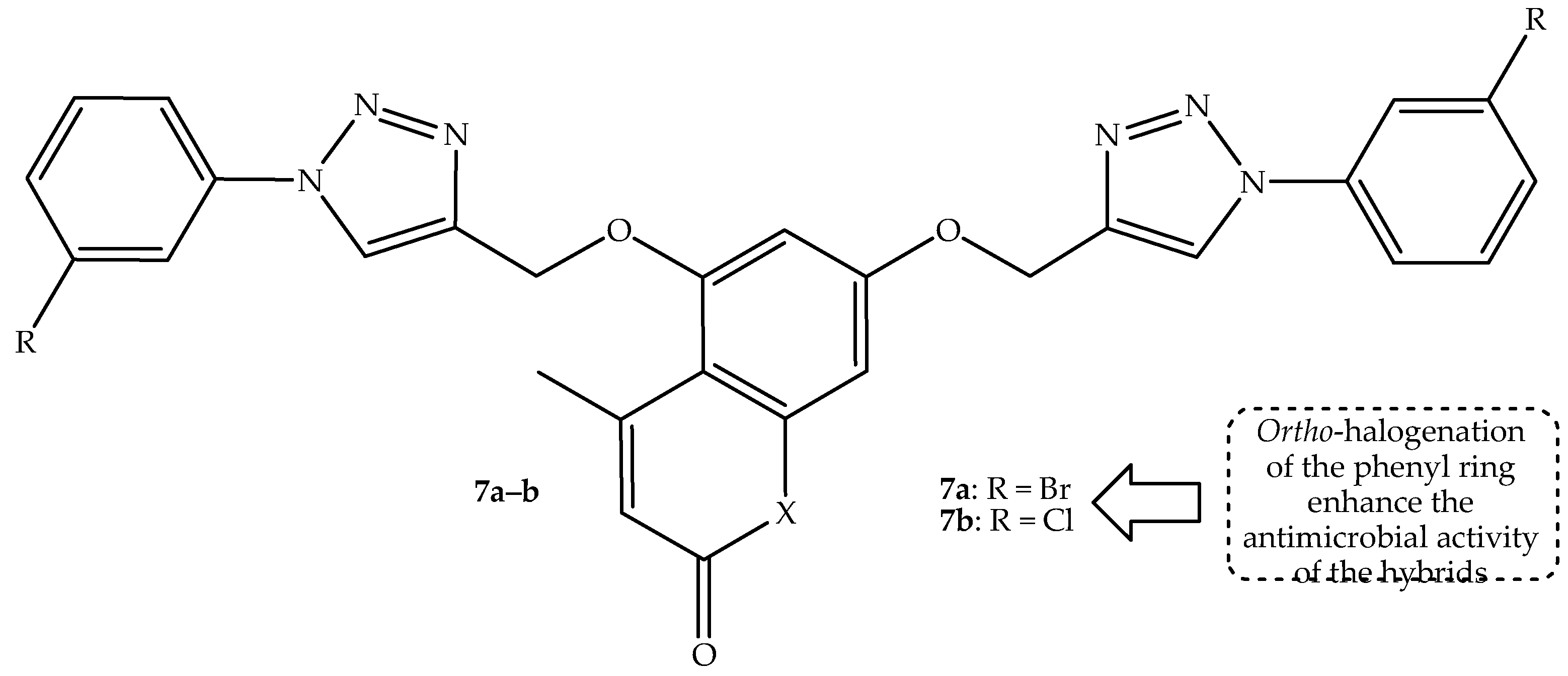

Another generation of coumarin–bis-triazole hybrids was synthesized and reported by Dhawan et al. [

59]. The compounds contain different alkyl chain lengths between the phenyl rings and the triazole linkers, and they were tested against two fungal (

C. neoformans and

C. albicans) and different bacterial (

K. pneumonia,

P. aeruginosa,

A. baumannii, and

E. coli) strains in vitro. The hybrids displayed disappointing antimicrobial activity, with no significant trend against the used strains. It was

ortho-halogenated hybrid

7a (bromo) and

7b (chloro), shown in

Figure 11, with percentage inhibition growth results shown in

Table 7, which display better activity among the synthesized compounds against

K. pneumonia and

C. albicans, illustrating that bromo and chloro groups can improve the antimicrobial activity of the drugs [

59]. This was also reported by Perz et al. [

60]. Therefore, further structural modification and in silico ADMET studies are recommended for these two compounds.

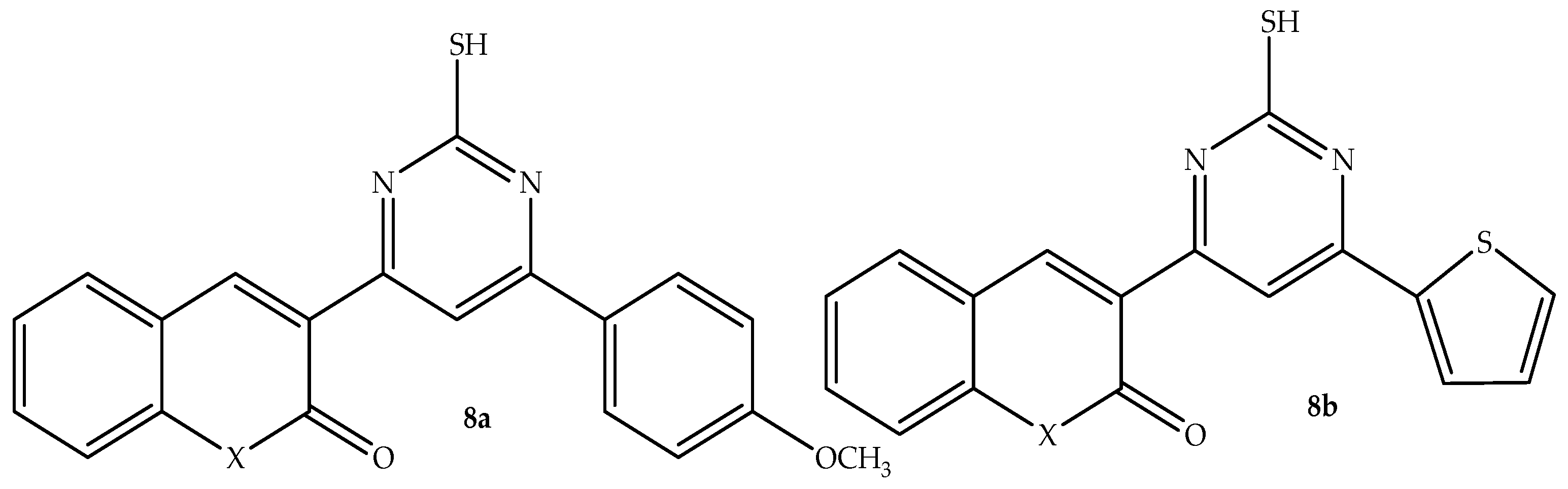

The contribution of Chalcones to the development of heterocyclic compounds triggered Abd-Elhussain et al. [

61] to synthesize chalcone–thiourea-linked coumarin hybrids and evaluate them against different microbial strains to produce potent drugs for microbial infections. The antibacterial findings showed that compound

8a (depicted in

Figure 12) exhibited better antibacterial activity among the synthesized hybrids, with a zone of inhibition (depicted in

Table 8) ranging from 10 to 17 mm, compared to 15 to 22 mm of ciprofloxacin against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial strains. Although all the synthesized compounds showed promising antifungal activity, it was hybrid

8b (depicted in

Figure 12) that showed superior antifungal activity against

C. albicans, with a zone inhibition of 25 mm compared to 30 mm of fluconazole in vitro [

61]. Hence, more studies, including SAR, in silico, and more clinical studies, are needed for these two promising effective antimicrobial hybrids to reinforce these findings.

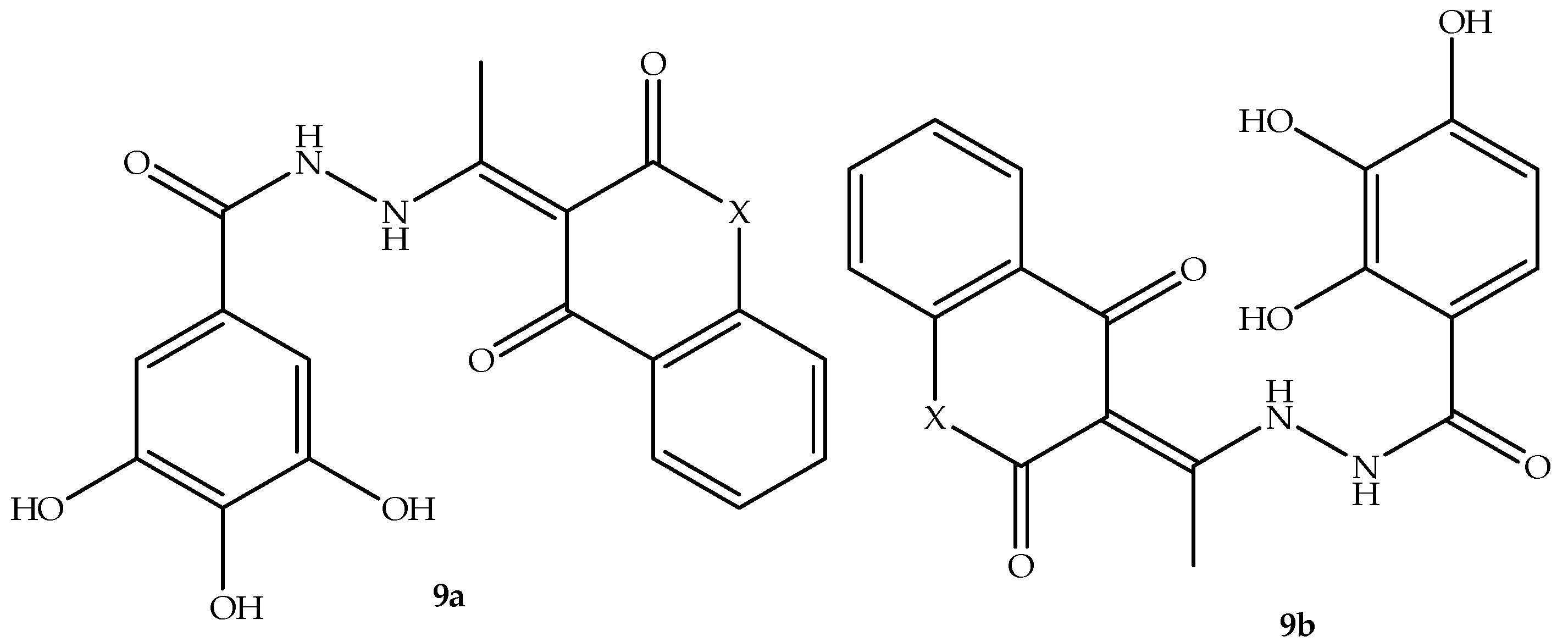

The progress of coumarin derivatives to clinical trials motivated many medicinal scientists to utilize the coumarin scaffold to develop new antimicrobial agents. Thus, Simijonović et al. [

62] synthesized two pyrogallol–coumarin-based hybrids,

9a–

b, displayed in

Figure 13, and assessed their antimicrobial effect against thirteen antibacterial and three fungal strains, with tetracyclines and fluconazole used as reference drugs in vitro. Although the synthesized hybrids exhibited inferior results in comparison to reference drugs, they displayed a promising antibacterial effect, which was dependent on the type of bacterial strains used, with MMC and MIC values ranging between 0.8 and 2.70 mM. Notably, these hybrids exhibited better antibacterial activity against

P. mirabilis ATCC 12,453 compared to other bacterial strains, with MMC and MIC of 0.17 and 0.08 mM, respectively. Additionally, hybrid

9b displayed better antibacterial effects against several bacterial strains compared to

9a. Moreover, when it comes to fungal strains, the hybrids exert promising antifungal activity against

C. albicans, exhibiting MIC and MMC values between 0.17 and 1.35 mM, with hybrid

9a displaying remarkable antifungal activity, as displayed in

Table 9 [

62]. The anti-biofilm activity results depicted that hybrid

9b exhibited better anti-biofilm activity, especially against

S. aureus ATCC 25923, with a BIC

50 value of 1.02 mM, whereas hybrid

9a showed no activity. This illustrates that hybrid

9b was the most effective compound. However, more studies focused on aspects such as toxicology, in vivo, and the mechanism of action are recommended to supplement these findings [

62].

An indole–triazole-linked coumarin hybrid

10, shown in

Figure 14, was synthesized by Khan et al. [

63] and assessed against

S. aureus and

E. coli bacterial strains and

C. albicans fungal strain in vitro, using tetracycline and fluconazole as reference drugs. Hybrid

10 displayed moderate antimicrobial activity against bacterial and fungal strains, with zone inhibition values (shown in

Table 10) ranging from 10 to 16 mM, compared to 20 to 28 mM for the reference drugs, in a concentration-dependent manner. Notably, this compound showed more antibacterial activity against

S. aureus compared to

E. coli [

63]. Hence, this compound’s mechanism of action was assessed on Thymidylate Kinase (PDB ID: 4QGG) and Dihydrofolate Reductase (PDB ID: 3SRQ) proteins, and it displayed better interaction with the amino acid residues via the hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and aromatic bonding, exhibiting docking scores of −9.657 kcal/mol and −9.102 kcal/mol compared to −7.270 kcal/mol and −8.259 kcal/mol of tetracycline. Therefore, this compound could be a potential replacement for tetracycline, as it binds better with the targeted proteins compared to tetracycline [

63]. Hence, more studies are recommended to further assess this compound.

A series of triazole-linked coumarin hybrids were synthesized by Manda et al. [

64] and evaluated against fungal strains, including

C. albicans,

A. fumigatus, and

A. niger, with fluconazole and griseofulvin utilized as reference drugs. The antifungal findings displayed hybrid

11 (depicted in

Figure 15) as the significant antifungal active hybrid among the synthesized compounds against

A. niger and

C. albicans, with MIC values of 31.25 µg/mL, which is higher than those of reference drugs, as depicted in

Table 11 [

64]. Consequently, this compound displays a good binding affinity towards the tubulin

α-β heterodimer protein, showing H bonding, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions with amino acid residues, exhibiting a docking score of −10.5 kcal/mol compared to −8.2 kcal/mol of griseofulvin. Notably, the type of substituents introduced in the synthesized hybrids influenced the antifungal activity of the hybrids, as hybrid

11 depicted that the presence of the indole in this hybrid improved its interaction with the amino acid residues, whereas its destruction resulted in compromised antifungal activity [

64]. Overall, this hybrid showed remarkable antifungal activity, and it could be a potential lead facilitating the discovery of new antifungal agents. Hence, more studies, including Swiss ADMET, in vitro bacterial studies, and in vivo evaluations, are recommended for this compound.

Abumelha et al. [

65] synthesized a generation of thiophene–coumarin hybrids and evaluated them for their antimicrobial activity against four bacterial and two fungal strains, in vitro. The hybrids were developed by varying the functional groups attached to the third position of the thiophene moiety and replacing sulfonamide with carboxamide [

65]. The hybrids displayed varied antimicrobial activity against the pathogens with MIC values comparable to those of ampicillin and flucytosine. Notably, hybrid

12 (displayed in

Figure 16), displayed consistent promising antimicrobial activity among the synthesized compounds, with MIC values (displayed in

Table 12) in a range of 38–144 µg/mL compared to 35–121 µg/mL of ampicillin against the bacterial strains and 88–117 µg/mL compared to 126–144 µg/mL of flucytosine against fungal strains, respectively. However, against

E. coli, this compound displayed less activity compared to some hybrids [

65]. The molecular docking findings revealed that the hybrids exhibited π-H and hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino acid residues, with hybrid

12 displaying the highest binding energy of −7.2776 kcal/mol against the 4URO protein [

65]. Moreover, in silico Swiss ADME findings also corroborated the in vitro findings, displaying this compound as the most promising drug, as it exhibited improved pharmacokinetics with a harmonic balance in molecular weight, bioavailability, TPSA, and lipophilicity, despite violating Lipinski’s rule [

65].

SAR displayed that the presence of 2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carbonyl and thiophene moieties influenced the interaction of the hybrid with bacterial enzymes [

65]. Furthermore, the phenylamino group enhanced the aromaticity and hydrogenation ability, leading to improved binding of the hybrids with specific targets in microbial cells. Moreover, the replacement of sulfonamide with the carboxamide group influenced the bioavailability and the solubility of the hybrids, leading to an improved antibacterial effect. Additionally, the presence of the

N-methyl group positively contributed to the antibacterial activity of the hybrids, as it improved their lipophilic nature, and substituting the hydroxyl group with a methyl group also improved the hydrophobic nature of the hybrids, leading to better biological activity, as this improved the hybrids’ ability to cross the cell membranes [

65]. In addition, the presence of the NH

2 group, in contrast to hydroxyl and methyl groups, further improved the hydrogen bonding formation capabilities, resulting in improved interactions [

65].

The DNA gyrase inhibition findings displayed that although the compounds displayed less inhibition compared to novobiocin, the sulfonamide-free terminal showed better DNA gyrase inhibition compared to the methyl-substituted sulfonamide, and the amide-bridged hybrids also displayed better DNA gyrase inhibition results compared to the diazo-bridged hybrids. This illustrates the importance of structural modification to the ability of the drug to bind with bacterial enzymes. Hence, the type of substituents and linkers must be considered when developing hybrid compounds. In essence, the synthesized thiophene–coumarin hybrids proved that structural modification could influence the antimicrobial activity of the compounds, as the compounds displayed promising antimicrobial activity. Therefore, more structural modifications are recommended for these hybrids to further improve their therapeutic effect [

65].

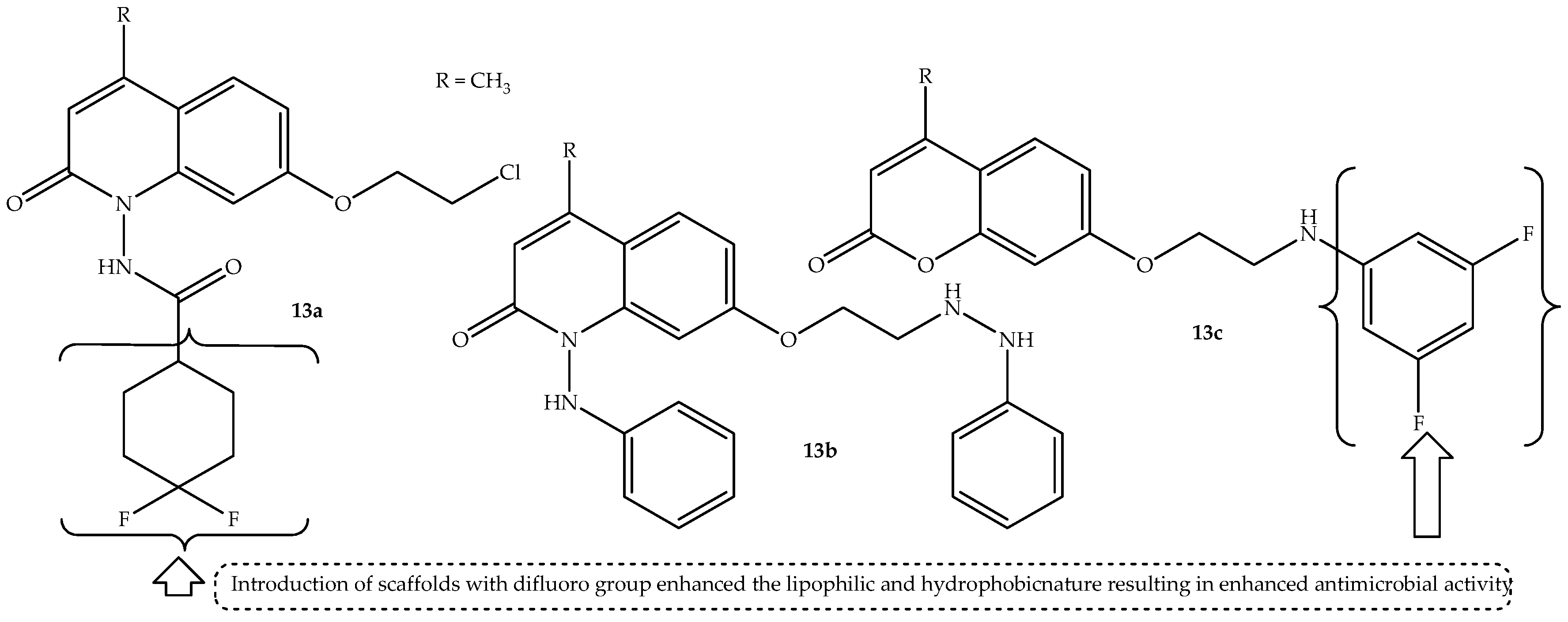

A generation of quinolone–coumarin hybrids were synthesized using a microwave irradiation method by Lakshmi et al. [

66] and colleagues, and they were biologically evaluated against different microbial strains in vitro. The hybrids displayed different bacterial effects against

E. coli,

S. pyogenes,

S. aureus, and

P. aeruginosa, with

E. coli displaying more susceptibility to the hybrids. Additionally, against the antifungal strains, the compounds showed promising antifungal effect against both

C. albicans and

A. niger, displaying compromised antifungal activity against

A. fumigatus. Notably, hybrid

13a–

c (depicted in

Figure 17) displayed a significant antibacterial effect against

E. coli compared to other synthesized hybrids and the standard drug (ciprofloxacin), with MIC values of 15.62 μg/mL compared to 31.25 μg/mL of ciprofloxacin, as shown in

Table 13. These hybrids also displayed remarkable antifungal activity compared to their counterparts, showing MIC values of 31.25 μg/mL (except

13c against

A. niger with MIC = 62.25 μg/mL) compared to 62.5 μg/mL and 125 μg/mL of the standard drug (griseofulvin) against both

C. albicans and

A. niger, respectively [

66].

Consequently, these hybrids displayed good binding interaction with the tubulin alpha beta heterodimer and peptide formylase receptor, with binding energies ranging between −8.8 and −9.4 and −7.7 and −8.5 compared to −7.6 and −7.1 of griseofulvin and ciprofloxacin, respectively. The molecular docking studies displayed that the hybrids bind better with the amino acid residues of the pathogens via π-cation, hydrogen bonding, π-alkyl, π-σ, π-π, and van der Waals forces interaction [

66]. The SAR displayed that the introduction of difluorocyclohexanecarboxamide resulted in hybrid

13a with enhanced lipophilicity, leading to improved antimicrobial activity. Similarly, attaching phenyl hydrazine to the first and seventh positions of the quinolone moiety resulted in hybrid

13b with improved biological activity, with the incorporation of 2,4-difluoroaniline enhancing the antimicrobial activity of hybrid

13c. In essence, the nature of substituents in these hybrids influenced their antimicrobial activity, with the introduction of scaffolds with difluoro groups increasing their lipophilic and hydrophobic nature, resulting in enhanced antimicrobial activity [

66]. Therefore, these encouraging findings depict that these hybrids are potent antimicrobial agents. However, more studies, including in vivo findings, are recommended.

Allah et al. [

67] synthesized isatin–coumarin-based hybrids as potent antimicrobial agents. The compounds were varied by introducing different scaffolds between the isatin and coumarin moieties. The hybrids exhibited different antibacterial activity, with inhibition zones (depicted in

Table 14) ranging between 1 and 3 mm compared to 4–5 mm of the standard drugs against

B. subtilis,

S. aureus, and

E. coli, in vitro [

67]. Hybrids

14a–

c (depicted in

Figure 18) displayed promising antibacterial activity compared to their counterparts, especially against Gram-positive bacterial strains. This illustrates the importance of

N-(3-chlorophenyl) pyrrole and pyrazole, furan, and dibenzo[b,e][1,4]diazonin to the antimicrobial activity of these compounds, with hybrids without these moieties showing less activity [

67]. Although these hybrids are displaying potential antibacterial activity, more studies, including in silico ADMET, molecular docking, and clinical trials, are recommended for these hybrid compounds to validate the current findings.

A series of coumarin–benzimidazole hybrids with varied substituents at different positions of the benzimidazole moiety were developed by Arya et al. [

68] and evaluated against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains, with vancomycin, meropenem, and polymyxin-B utilized as standard drugs. Hybrid

15a (butyl-substituted) and

15b (p-tolyl-substituted), shown in

Figure 19, were the compounds with the most antibacterial activity among the synthesized compounds and vancomycin against the Gram-positive bacterial strain (

K. pneumoniae) with MIC values of 6.25 µg/mL, as depicted in

Table 15.

Notably, other synthesized compounds were inactive against all the strains [

68]. Additionally, the cytotoxicity results indicated that these compounds showed better activity compared to the standard drugs at a lower concentration (50 µM). However, increasing the concentrations (>100 µM) decreased the normal tissue survival rates by 3-fold. Therefore, these compounds were further submitted for in vivo evaluations against

K. pneumoniae-infected mice. The compounds significantly reduced the bacterial counts comparable to meropenem at increased doses. Hence, these compounds can be recommended as potential replacements for meropenem, and they could be a steppingstone towards new therapeutic agents for the treatment of

K. pneumoniae-related infections. Thus, in silico, the compounds displayed good drug likeness and physicochemical properties, with only hybrid

15b violating Lipinski’s rule. Moreover, the compounds display high BBB-penetrating ability, illustrating that they could be potent for the central nervous system infections. Furthermore, these two antibacterial compounds showed no carcinogenicity or mutagenicity. These findings confirm these two drugs as potential treatments for bacterial infections [

68].

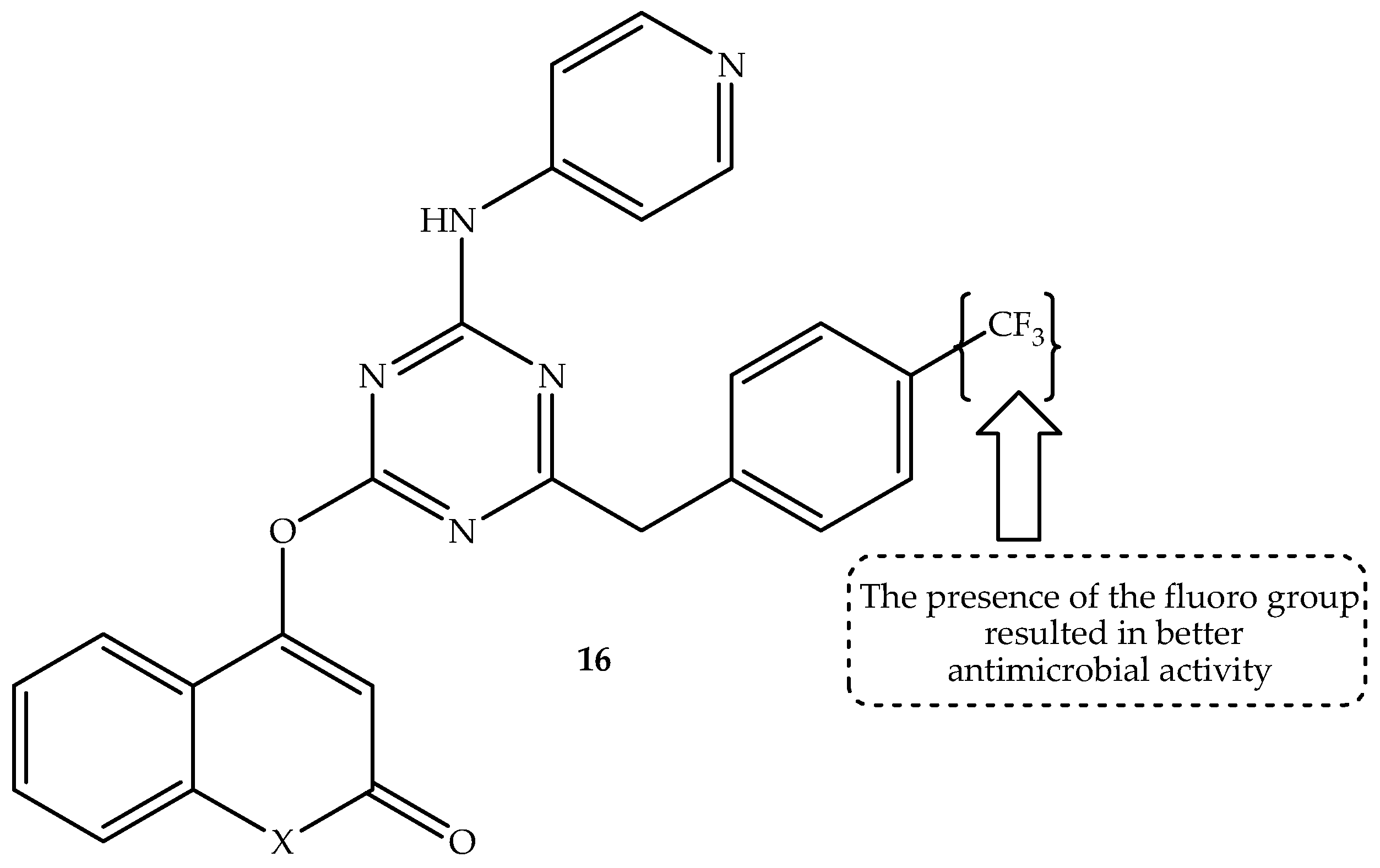

Zala et al. [

69] hybridized pyridine, benzothiazole, and coumarin via s-triazine linker, resulting in novel potential antimicrobial candidates when tested against selected bacterial and fungal strains in vitro. Norfloxacin and griseofulvin were used as a reference drug. The hybrids displayed moderate to good antibacterial activity on different strains [

69]. As displayed in

Table 16, among the synthesized coumarin hybrids, compound

16 (displayed in

Figure 20) was the most promising, with an MIC value of 25 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, and 12.5 µg/mL compared to 10–50 µg/mL of norfloxacin against human

B. subtilis,

C. tetani, and

E. coli strains, respectively. Consequently, hybrid 16 was also the most promising antifungal agent with comparable antifungal activity to griseofulvin, displaying MIC values of 100 µg/mL and 500 µg/mL against

T. rubrum and

C. albicans antifungal strains, respectively [

69].

Moreover, this compound was submitted for in silico molecular docking on

S. aureus dihydropteroate synthetase. It displayed a potent binding ability with

S. aureus dihydropteroate synthetase, showing a binding score of −6.596 kcal/mol compared to −8.198 kcal/mol of the co-crystallized inhibitor. Notably, the presence of the electron-withdrawing group (CF

3) was reported to improve the antimicrobial activity of this hybrid. Hence, it was the strongest antibacterial candidate among the synthesized coumarin hybrids [

69]. However, more studies, such as in vivo studies, are recommended for these coumarin-based hybrids to supplement these findings.

A generation of coumarin-1,2,3-triazole hybrids was synthesized through copper(I)-catalyzed azide alkyne cycloaddition by Jaggal and coworkers as potential antibacterial agents in comparison to streptomycin [

70]. Among the synthesized hybrids, a marginal difference displayed hybrid

17a–

b (shown in

Figure 21) as the most promising antibacterial active compounds, with MIC values between 0.5 and 4 μg/mL compared to 0.5–1 μg/mL of streptomycin against selected bacterial strains, including

S. aureus,

S. pyogenes,

S. typhi, and

P. aeruginosa (the MIC values are summarized in

Table 17).

The SAR showed that the position and type of substituents present in these compounds influenced their antibacterial activity, with the halogenated

17a (chloro group at position 6 of coumarin) and benzo-fused

17b (5,6-benzo coumarin) displaying remarkable activity compared to their counterparts. The improved π-π interaction of these drugs was suspected to be responsible for the enhanced activity [

70]. Hence, in silico molecular docking was conducted to test the interaction of these drugs with amino acid residues of

S. aureus dihydropteroate synthase. These compounds showed good binding energies with binding scores between −8.4 kcal/mol to −9.6 kcal/mol via pi–anion, carbon–hydrogen bonding, π-π stacked, hydrogen bonding, pi–alkyl, and alkyl interactions. Additionally, hybrid

17a–

b displayed better pharmacokinetics and improved oral bioavailability due to higher intestinal absorption, in silico. Moreover, these hybrids displayed better tissue distribution, were unable to pass the BBB, and posed no toxicity threats to normal tissues. However, the compounds displayed some toxic traits as they inhibited Pg-substrates and CYP1A2, suggesting a possibility of drug–drug interactions. Therefore, further investigations, including in vivo evaluations, are recommended for these two antibacterial active hybrid compounds [

70].

The DNA intercalation and the pharmacological properties of naphthalimide prompted Rana et al. [

71] to synthesize a generation of coumarin–naphthalimide hybrids with varied substituents at positions 6 and 7 of the coumarin and test them against selected bacterial strains. The coumarin–naphthalimide hybrids were modified via the introduction of aromatic rings on the coumarin moiety, varying the type of linkers and chain length between the two scaffolds, inserting the carbonyl group between the two moieties, and replacing the piperazine ring. Hybrids

18a and

18b (displayed in

Figure 22) exhibited remarkable antibacterial activity, with MIC values ranging between 1 µg/mL and 0.5 µg/mL against

S. aureus, respectively. Notably, most of the synthesized compounds displayed activity against

S. aureus compared to other bacterial strains in vitro [

71]. The SAR displayed that the presence of the electron-donating groups at positions 6 and 7 of the coumarin ring (such as in hybrids

18a–

b) was crucial for the antibacterial activity in comparison to the hybrids with electron-withdrawing groups. Additionally, replacing the piperazine ring with a propyl chain and aminopyridine linkers between the coumarin and naphthalimide moieties compromised the antibacterial activity of the compounds. Furthermore, changing the chain length with carbonyl groups, replacing coumarin with other heterocyclic scaffolds, and introducing substituents on the naphthalimide moiety also resulted in a loss of antibacterial activity [

71]. This illustrates the importance of naphthalimide, coumarin, and piperazine linkers in the antibacterial activity of these hybrids. Moreover, hybrids (

18a–

b) were evaluated for cytotoxicity against Vero cell lines, and they were non-toxic with CC

50 values of more than 50 µg/mL and a selective index of more than 12.5. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index, in comparison to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, displayed no antagonistic effect. Moreover, the in silico molecular docking studies revealed that hybrid

18a binds with amino acid residues of

S. aureus DNA gyrase via π-π stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions. Additionally, it was noted that hybrids

18a–

b are bacteriostatic, as they inhibit the topoisomerase IV enzymes [

71]. Hence, more studies, including in vivo evaluation, are recommended for these two drugs.

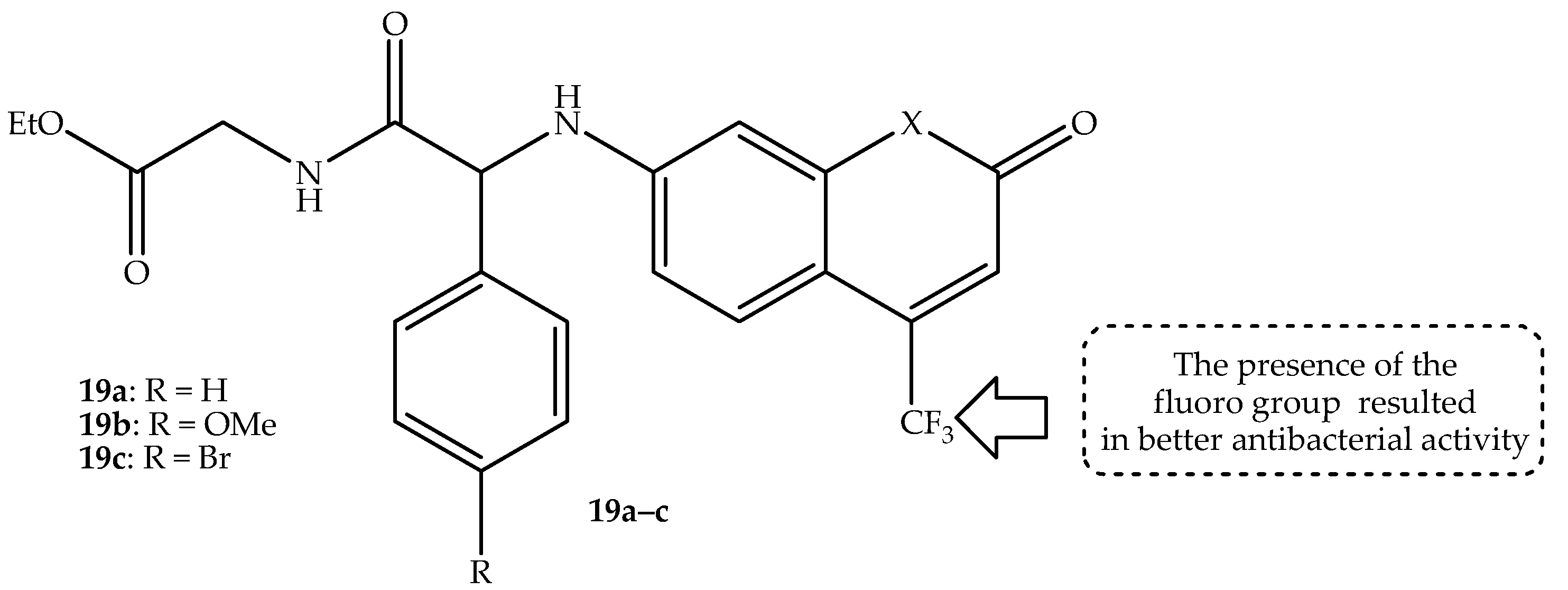

Kowalczyk et al. [

72] synthesized the trifluoromethyl-containing coumarin hybrids for the treatment of bacterial meningitis-related infections. In vitro, against several

E. coli and

S. aureus, the compounds displayed promising antibacterial activity with MIC and MBC values ranging from 0.58 to 1.25 µg/mL and 0.62–1.43 µg/mL, respectively. Notably, compounds containing the CF

3 group, such as hybrid

19a–

c (depicted in

Figure 23), exhibited more antibacterial activity compared to the methyl group-containing hybrids. Additionally, the compounds were more selective towards the

E. coli compared to the

S. aureus strains, and this was ascribed to the presence of lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of the

E. coli strains [

72]. The cytotoxicity tested against normal BALB/c-3T3 and αT3-1 cell lines revealed that the compounds showed no toxic threats towards normal tissues, with excellent cell viability percentages of more than 96% at low concentrations (0.5–1 µg/mL). This showcased these hybrids as potent bactericidal agents, as their cytotoxicity results were comparable or lower to the used FDA-approved antibiotics, including bleomycin, ciprofloxacin, and cloxacillin. Additionally, the in vivo evaluations of these coumarin hybrids were performed on the cerebrospinal fluid of a sheep to test their ability to pass the BBB [

72]. Hybrid

19a displayed outstanding ability to pass the BBB, as more concentrations were observed in the cerebrospinal fluid compared to its counterparts. This was attributed to its structural architecture, and the presence of CF

3 further improved its ability to pass the BBB, as CF

3 improves the lipophilic nature of the compounds and C-F bonds can inhibit metabolic degradation, leading to improved bioavailability. Therefore, hybrid

19a can be recommended for the treatment of bacterial infections, especially in the central nervous system. However, more in vivo studies using a wide range of concentrations, instead of only one dose, were recommended to reinforce these findings [

72]. Hence, further research on these components is still sorely needed.

Another series of coumarin hybrids were synthesized by Betti et al. [

73] and evaluated to determine their antimicrobial activity against selected bacterial and fungal strains. The synthesized hybrids displayed better antimicrobial activity compared to their parent compounds, and the presence of azomethane and nitrogen atoms incorporated in these hybrids positively influenced their antimicrobial effect [

73]. Compound

20a (shown in

Figure 24) exhibited an outstanding antibacterial effect in a concentration-dependent manner against all used bacterial strains, especially

E. coli. Additionally, the exceptional performance of hybrid

20a was supplemented by the presence of the 4-aminoantipyrine moiety, which improved the stability of this hybrid. Furthermore, the lipophilic nature of these compounds was enhanced by the ability of pi electron delocalization, resulting in enhanced bacterial membrane permeability. Notably, hybrid

20b (depicted in

Figure 24) exhibited remarkable antifungal activity among the synthesized hybrids against

C. albicans and

A. niger, with the presence of aromatic ring and hydrazine moieties being responsible for the improved interaction with fungal cells. Thus, the proposed antibacterial and antifungal action of these hybrids involves disruption of protein synthesis, DNA replication, membrane distribution and disruption, induction and generation of reactive oxygen species, and protein denaturation. Therefore, hybrid

20a–

b were recommended as potent antimicrobial agents [

73]. However, more studies are urgently needed to validate these findings and confirm these proposed mechanisms of action.

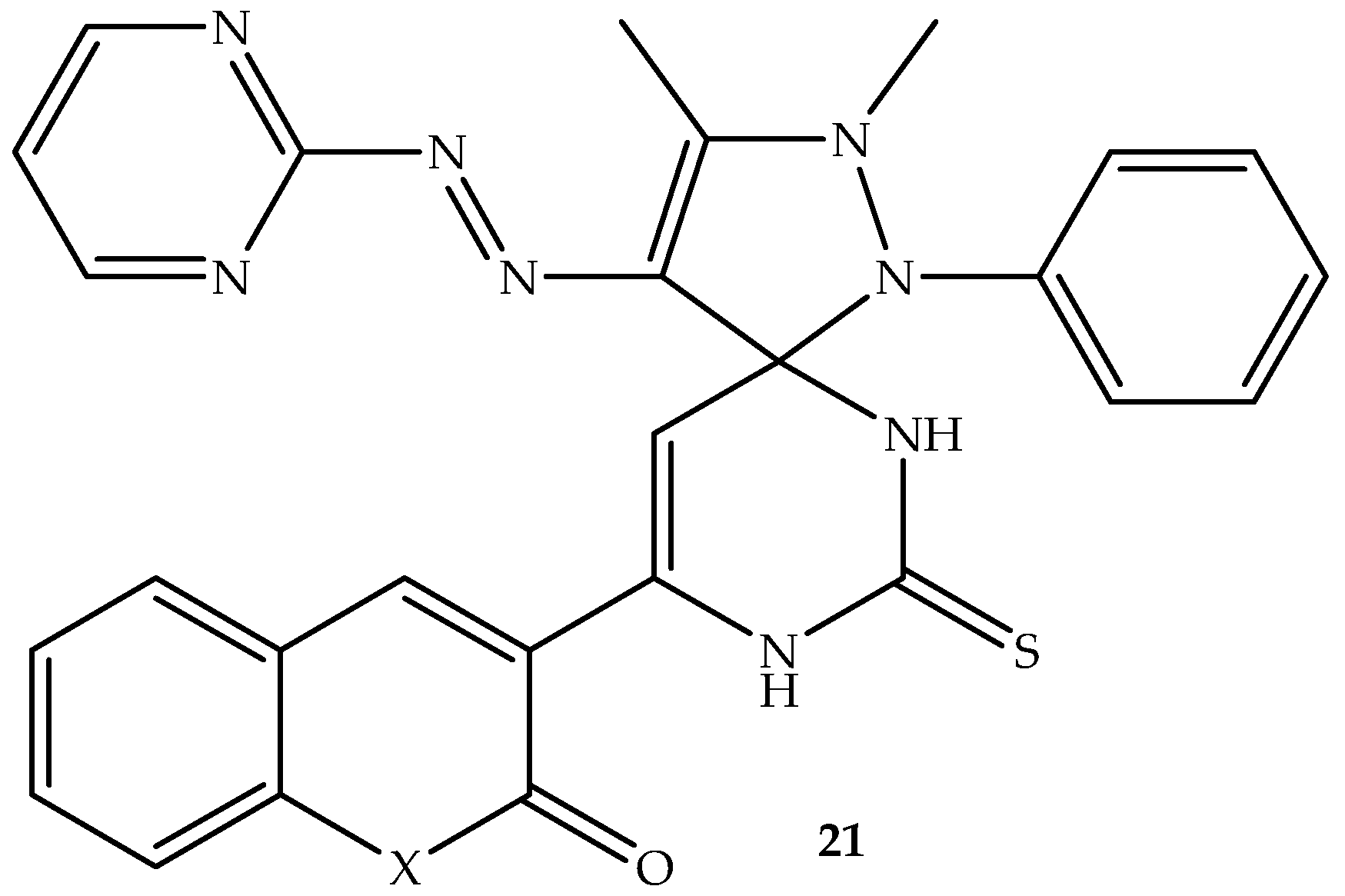

A series of spiro-heterocyclic coumarin hybrids were synthesized by Al-Burgus et al. [

74] and evaluated against

S. aureus and

E. coli bacterial strains. Among the five synthesized hybrids, compound

21 (depicted in

Figure 25) displayed remarkable activity against both bacterial strains in vitro [

74]. Hence, its ability to interact with DNA gyrase was studied in silico. The compound displayed better binding affinity with the DNA gyrase amino acid residues, displaying binding scores of −9.9 kcal/mol and −8.2 kcal/mol compared to −7.2 kcal/mol and −6.8 kcal/mol of clorobiocin against

E. coli and

S. aureus, respectively. The hybrids showed pi-anions, pi-alkyl, pi–sigma, amide-pi-stacked, and pi-cation interactions with amino acid residues via hydrogen bonding using lactones from the coumarin, pyrimidine, and thiol group. Although there are synthetic limitations, such as high costs, harsh conditions, and low yields of these spiro-heterocyclic coumarin hybrids, the findings revealed hybrid

21 to be a potential antibacterial candidate [

74]. Therefore, more studies are recommended for this compound.

Interesting findings were reported by Ungureanu et al. [

75] regarding the antimicrobial efficacy of 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl–thiazole–coumarin hybrids. The hybrids exhibited promising antibacterial activity, with MIC and MBC values that were superior to and comparable to the control drugs, especially against

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa, with

S. aureus showing more susceptibility to the hybrids compared to

P. aeruginosa. Hybrid

22a showed remarkable antibacterial activity comparable to that of ciprofloxacin, with MIC and MBC values between 15.62 and 31.25 µg/mL against

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa, and

S. aureus bacterial strains, as displayed in

Table 18 [

75]. The hybrids showed antifungal activity comparable with fluconazole against

C. albicans and

A. brasiliensis. Hybrids

22a–

c (shown in

Figure 26) exhibited the most promising antifungal activity against the selected antifungal strains, with MIC and MFC values between 7.81 and 31.25 µg/mL and 15.62 and 31.25 µg/mL, respectively [

75]. Notably, the synthesized hybrids were categorized as fungicidal and bactericidal as they displayed MIC/MBC and MIC/MBC ratios of less than four. Additionally, the SAR showed that introducing ether groups into position eight of coumarin compromised the antibacterial activity of the hybrids, with the presence of the hydrazone linker between coumarin and azomethine nitrogen moieties also influencing the antifungal activity.

Moreover, the presence of the hydroxyl group at position 7 of coumarin resulted in hybrid

22c with enhanced overall antimicrobial activity. Thus, this hybrid also exhibited noticeable antibiofilm activity against

P. aeruginosa; hence, it can be recommended as a promising candidate for the treatment of

P. aeruginosa-related infections. The introduction of bromine and a hydroxyl group at position 6 and aromatic ring on the coumarin scaffolds positively influenced the antibiofilm activity of these hybrids. The hybrids displayed good binding affinities compared to the novobiocin and displayed steric interactions with the amino acid residues [

75]. The in silico ADMET predictions revealed that hybrid

22c does not display any drug–drug pharmacokinetics interaction threats. However, it is among the list of hybrids with no BBB penetration capacity and low GI absorption, leading to compromised oral administration. Additionally, this hybrid showed high toxicity in silico, as it belongs to class III for acute oral toxicity [

75]. Hence, in vivo studies are recommended to reinforce these findings.

Loganathan et al. [

76] used Knoevenagel condensation to synthesize a series of potential antimicrobial coumarin–thiopyrans–imidazolidine hybrids. The hybrids were tested against several fungal and bacterial strains, and they displayed a promising antimicrobial effect. The MIC values depicted in

Table 19 reveal that hybrid

23a (displayed in

Figure 27) was the most antibacterial active compound among the synthesized hybrids, with an MIC value of 2 μg/mL compared to 4 μg/mL of ciprofloxacin against the resistant

S. aureus bacterial strain. Moreover, hybrid

23b (depicted in

Figure 27) was the most antifungal active compound among the synthesized hybrids, with comparable MIC values between 0.5 and 1 μg/mL to clotrimazole against

C. albicans and

A. niger fungal strains [

76]. Notably, the antimicrobial activity findings exposed that the combination of the coumarin and thiopyran–imidazolidine scaffolds resulted in enhanced biological activity, as the parent compounds exhibited far less antimicrobial activity compared to the hybrids. Additionally, the incorporation of para-substituted phenyl rings improved the biological activity of the drugs, as this improved the lipophilic nature of the hybrids. Therefore, hybrid

23a–

b can be potent antimicrobial agents [

76]. Hence, more evaluations, such as in silico and in vivo studies, are recommended for these hybrids.

Click chemistry reactions were utilized by Kangad et al. [

77] to synthesize potential antimicrobial coumarin–triazole hybrids. The hybrids exhibited moderate to good antimicrobial activity. However, the antimicrobial effect was inferior compared to that of ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and nystatin [

77]. Hybrids

24a–

b (depicted in

Figure 28) exhibited more antibacterial activity with MIC values of 125 µg/mL against

E. coli,

B. subtilis,

S. aureus, and

S. typhimurium strains, as depicted in

Table 20. The in silico molecular docking studies displayed that these compounds bind well with

C. albicans CYP51 enzymes via hydrophobic interactions, with binding energies between −9.56 to −10. 13 kcal/mol. This illustrates that these hybrids can be a potent treatment for

C. albicans-related fungal infections. However, further research was recommended for these hybrids [

77].