The Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum as Influenced by Antibiotic Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

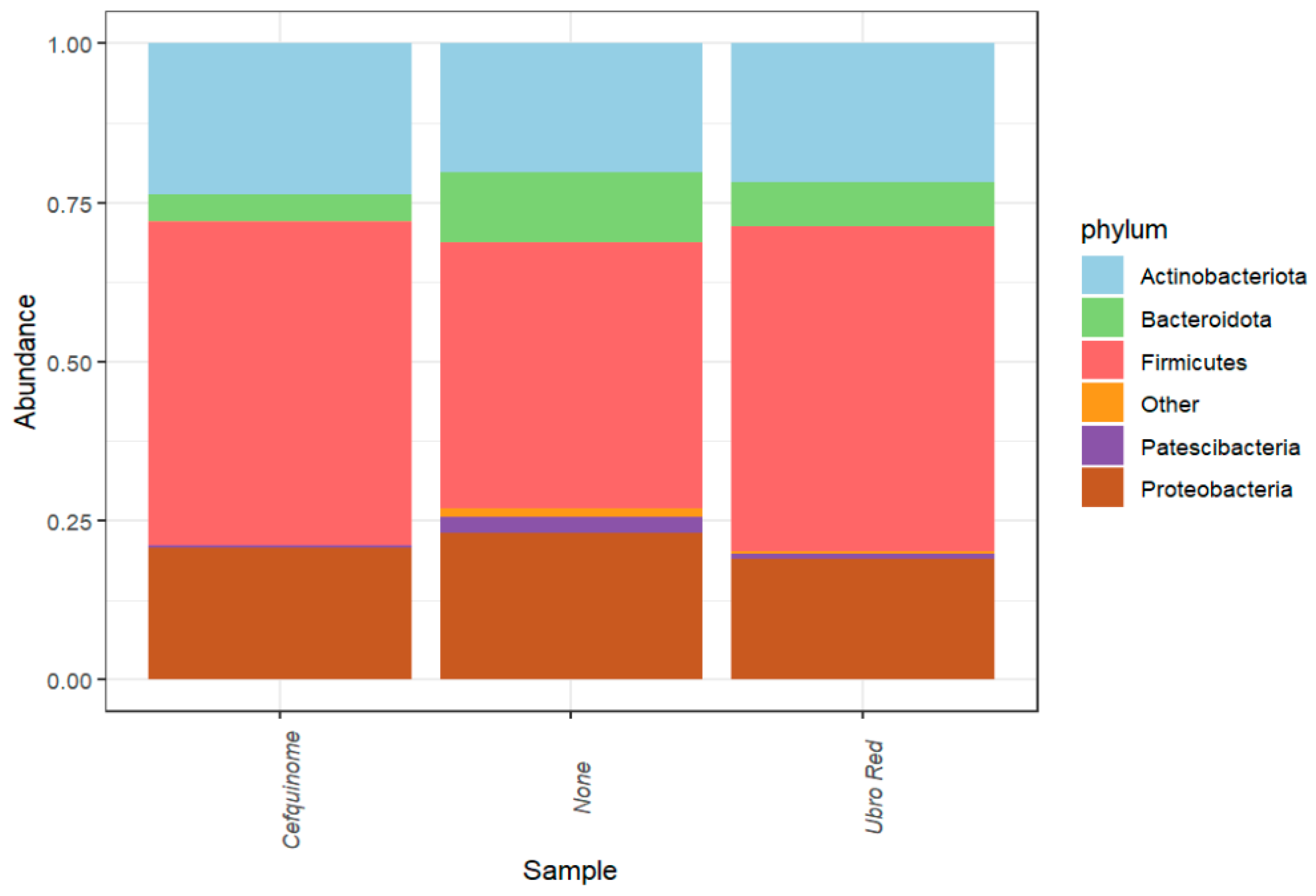

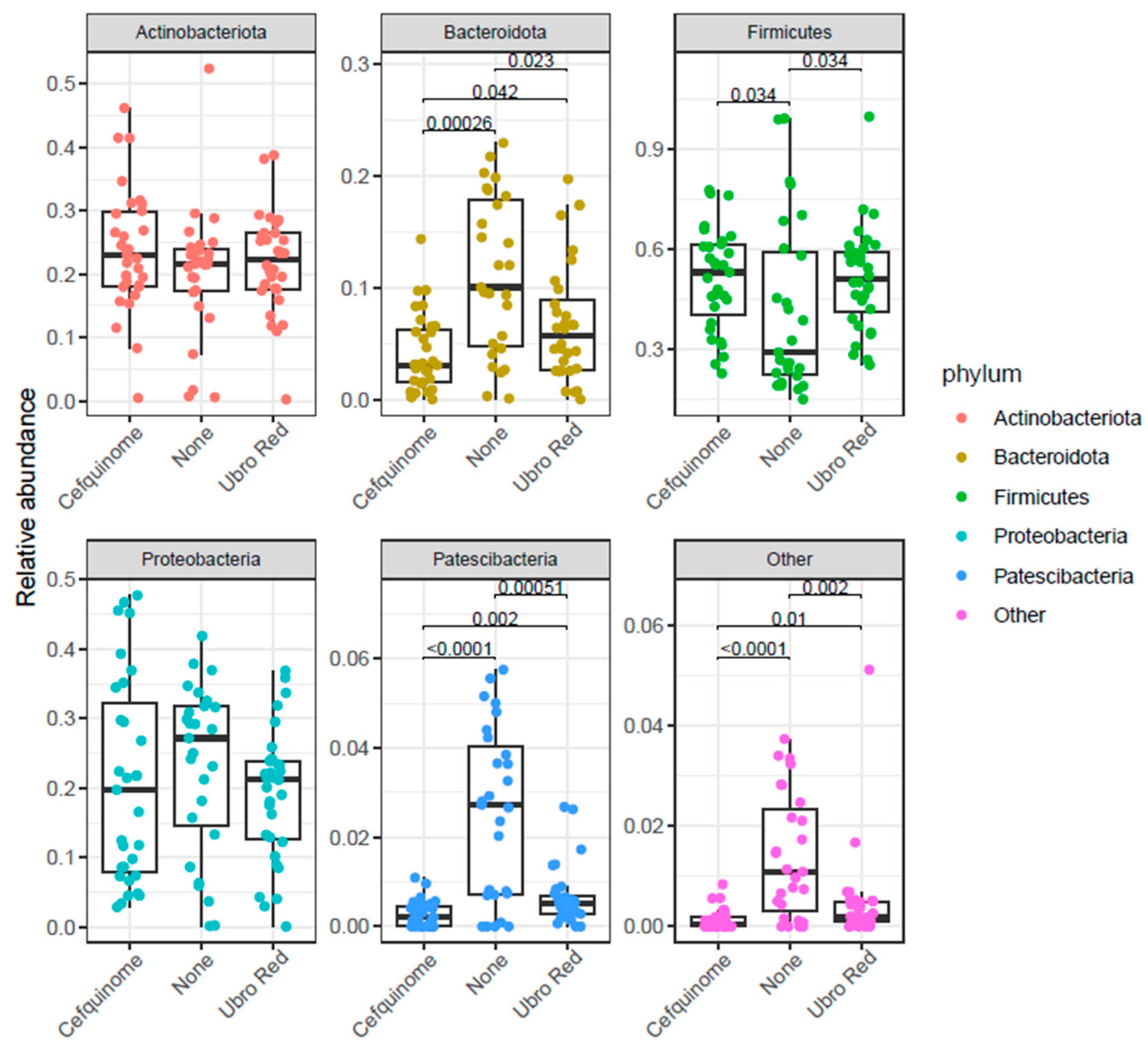

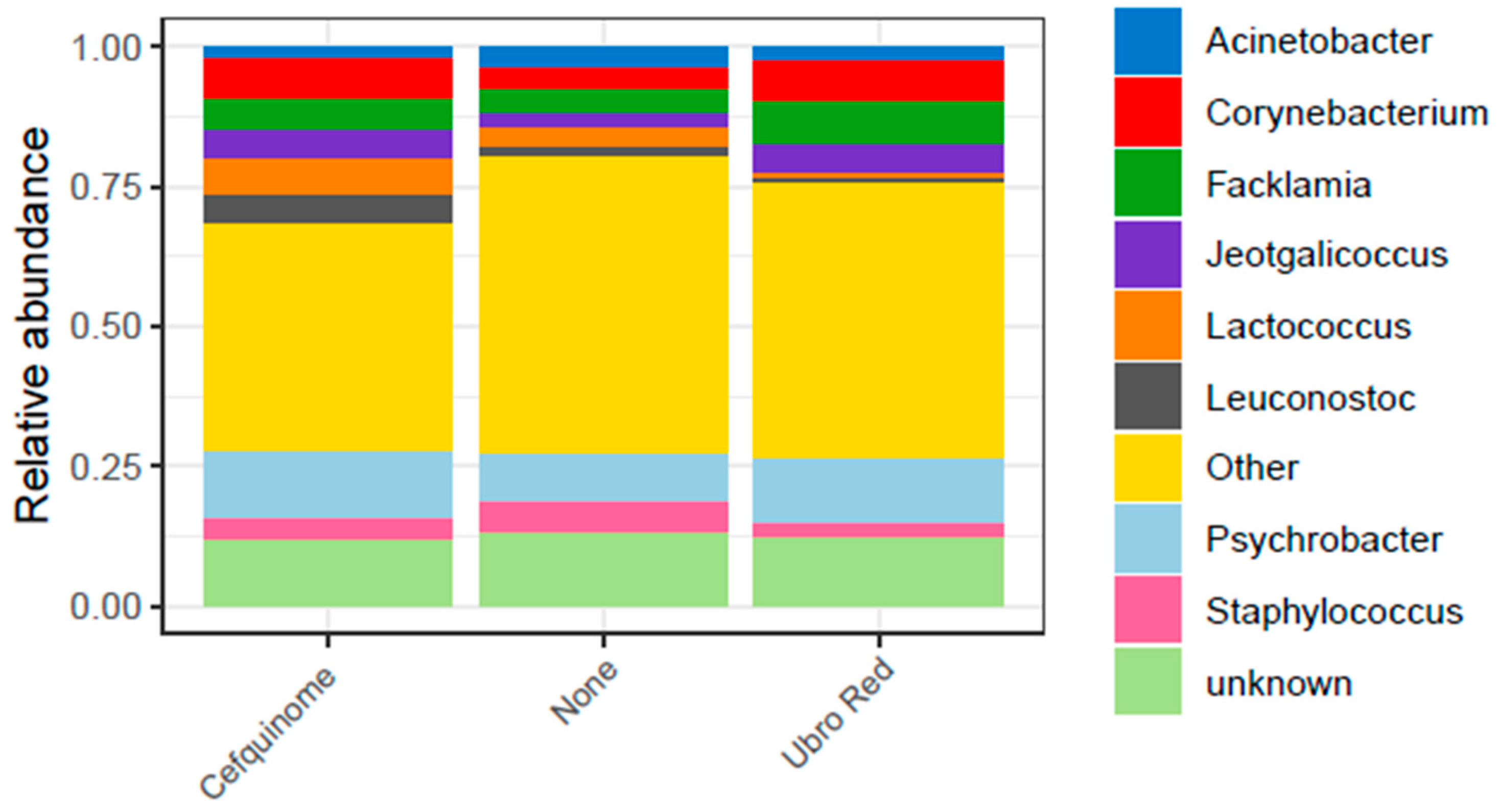

2.1. Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum Following Dry Cow Therapy

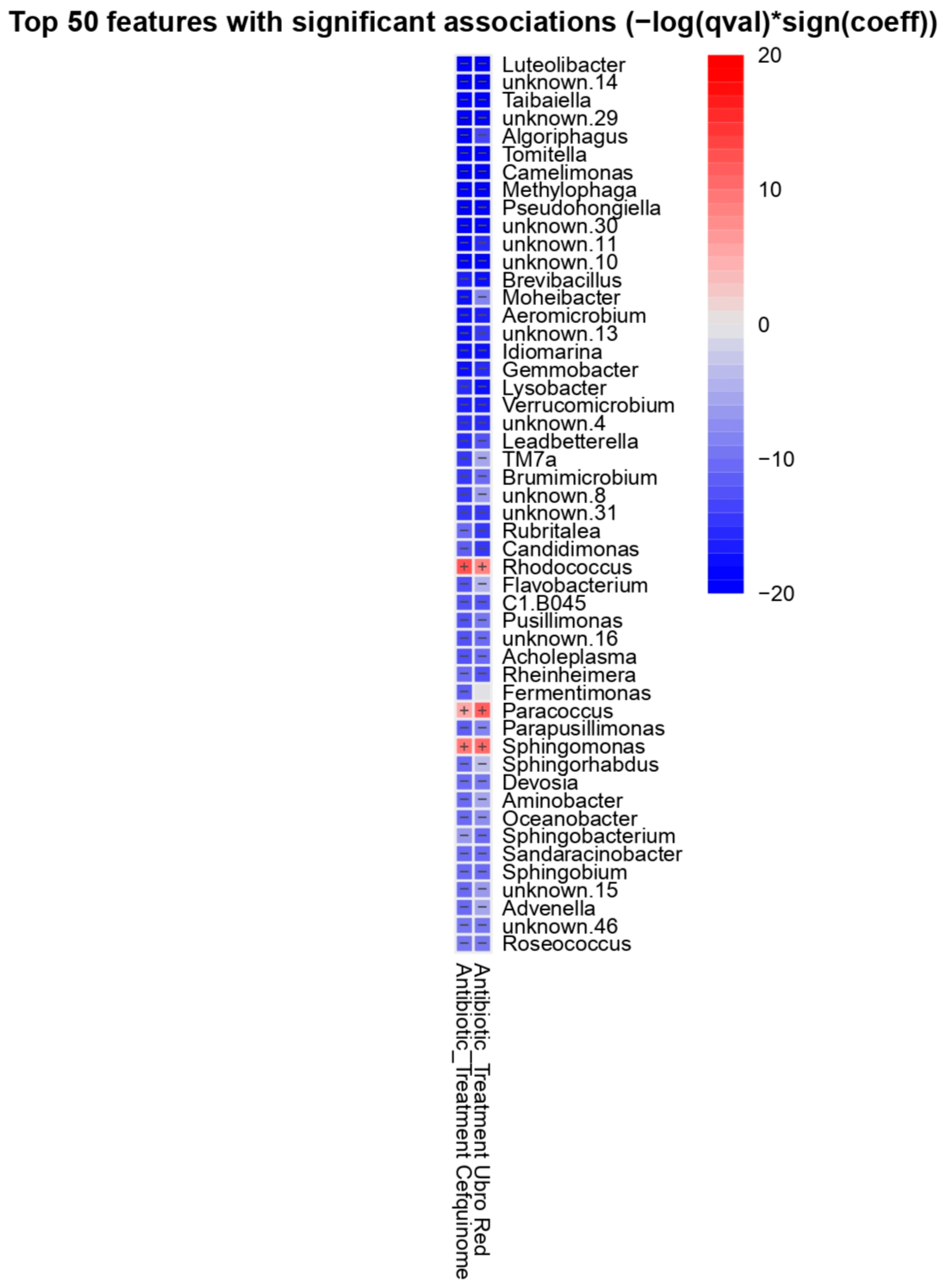

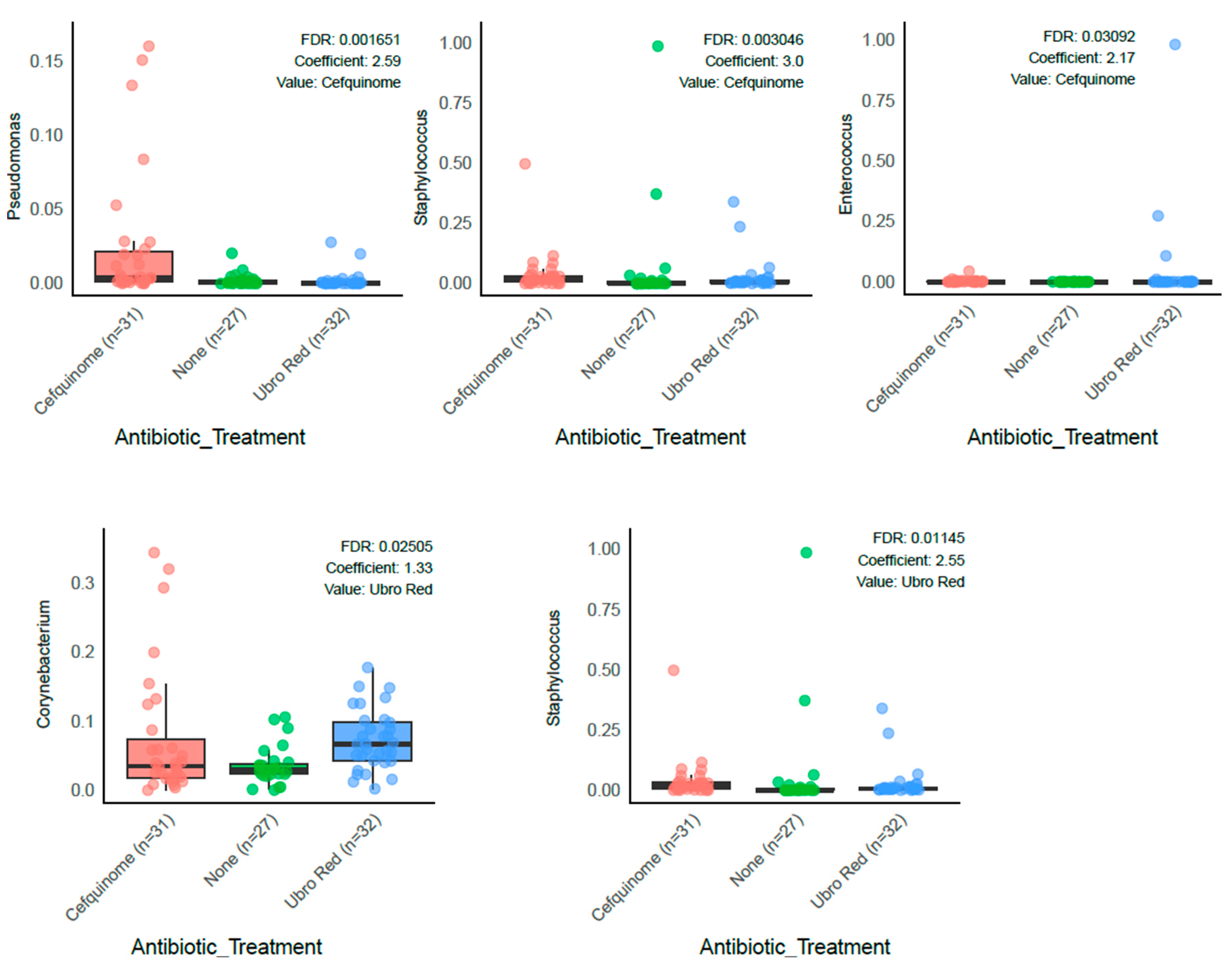

2.2. Differential Abundance Analysis

2.3. The Influence of Dry Cow Therapy on the Microbial Diversity of Bovine Colostrum

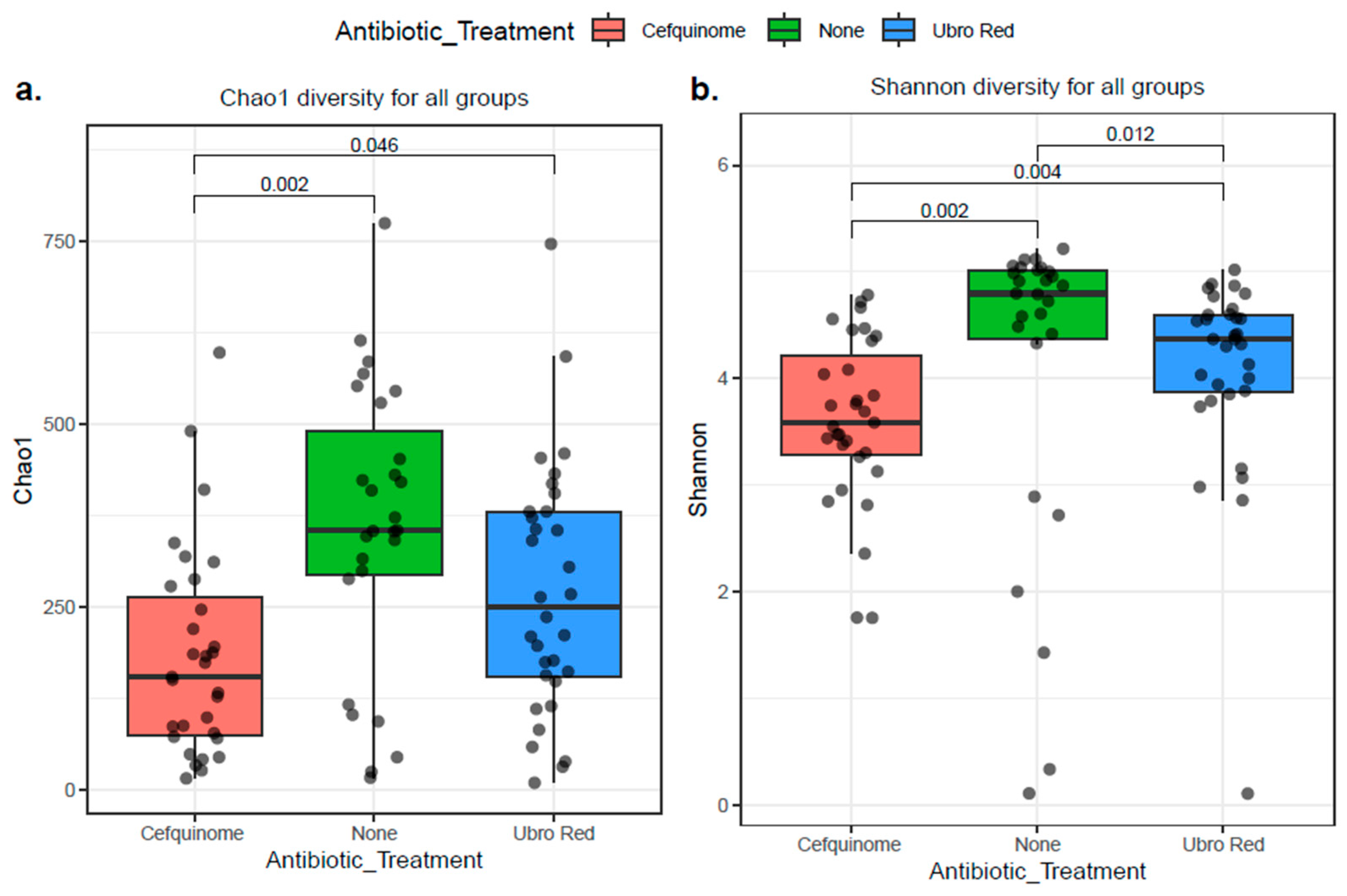

2.3.1. Alpha Diversity

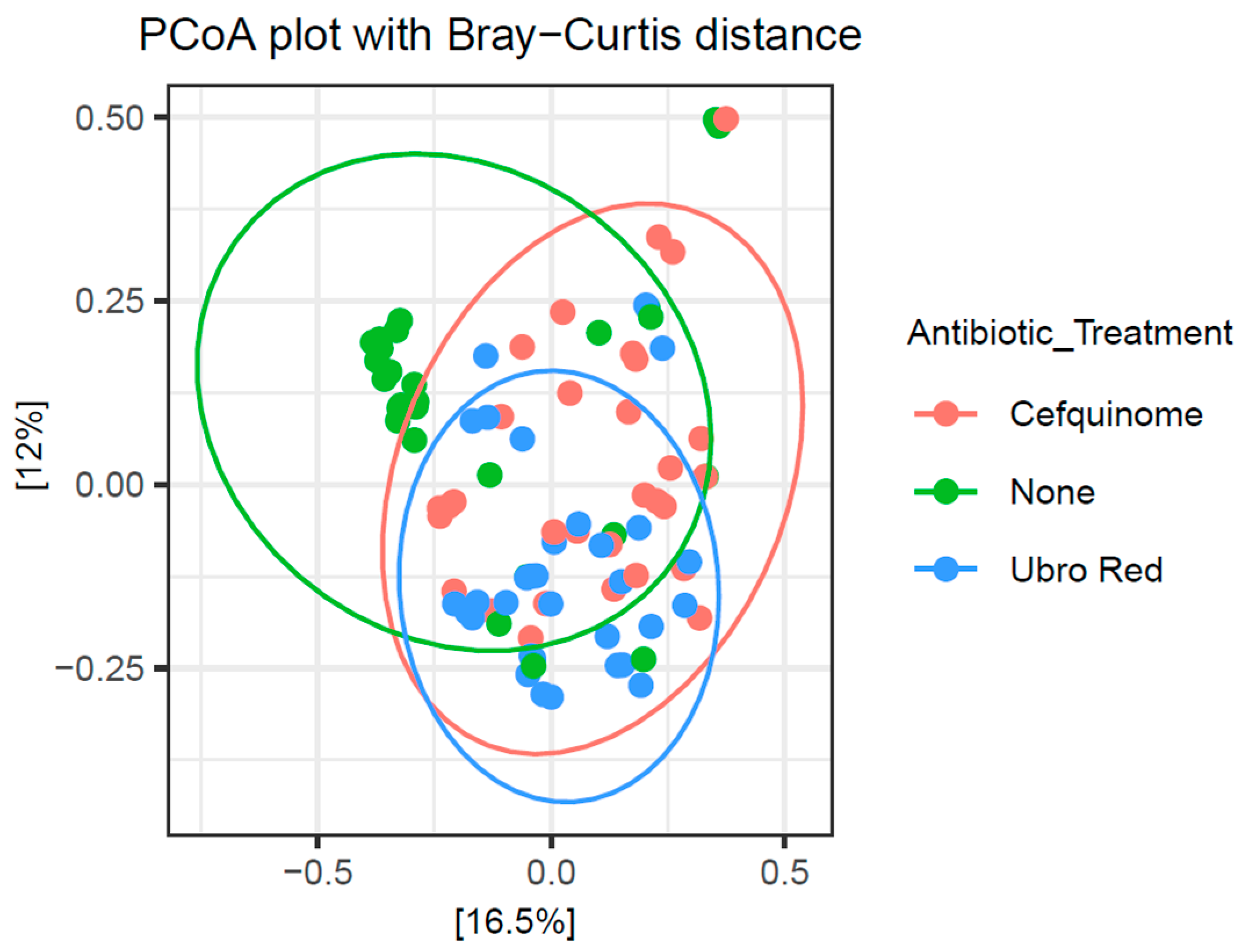

2.3.2. Beta Diversity

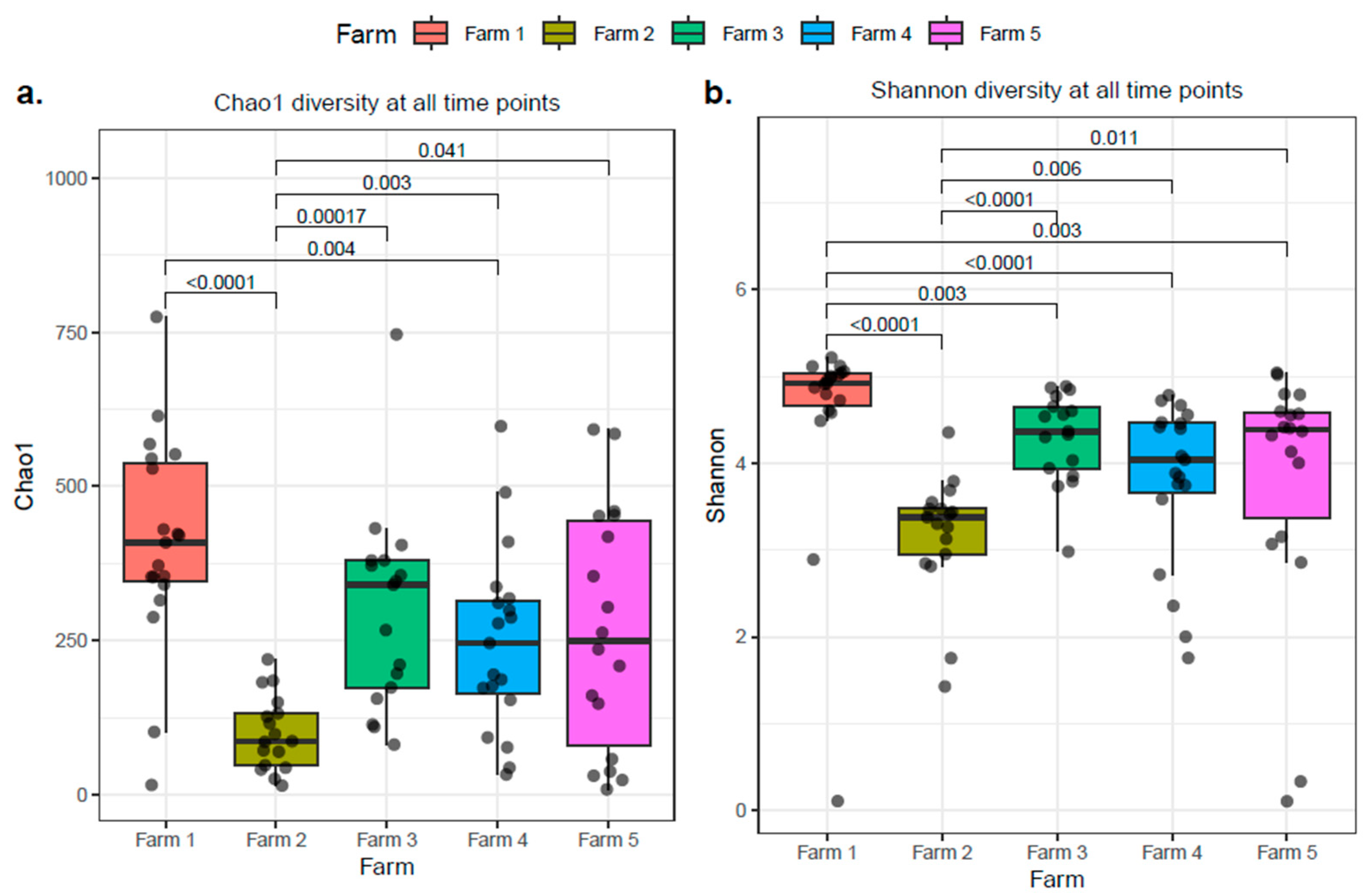

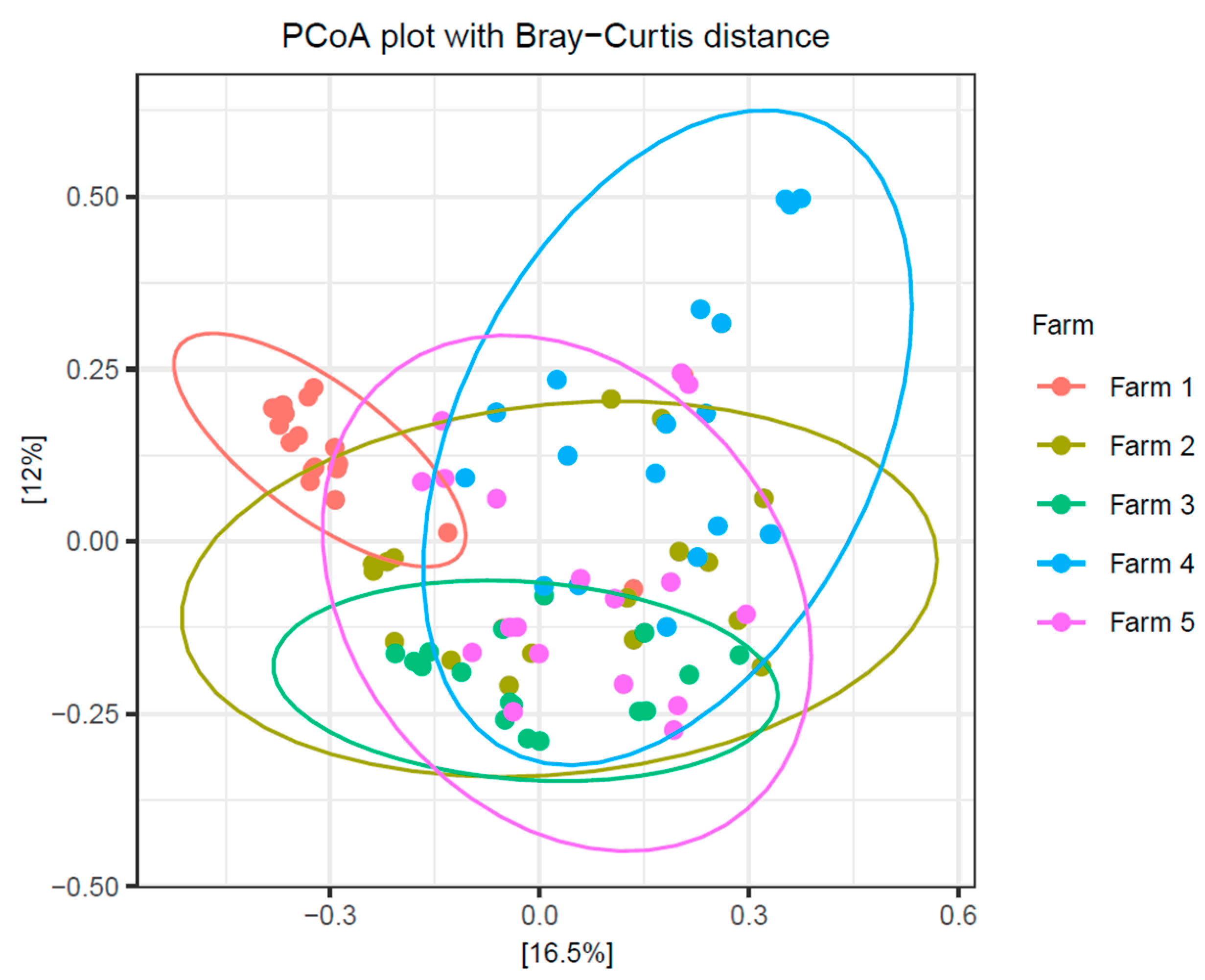

2.4. The Influence of Individual Farm Variation on Bovine Colostrum

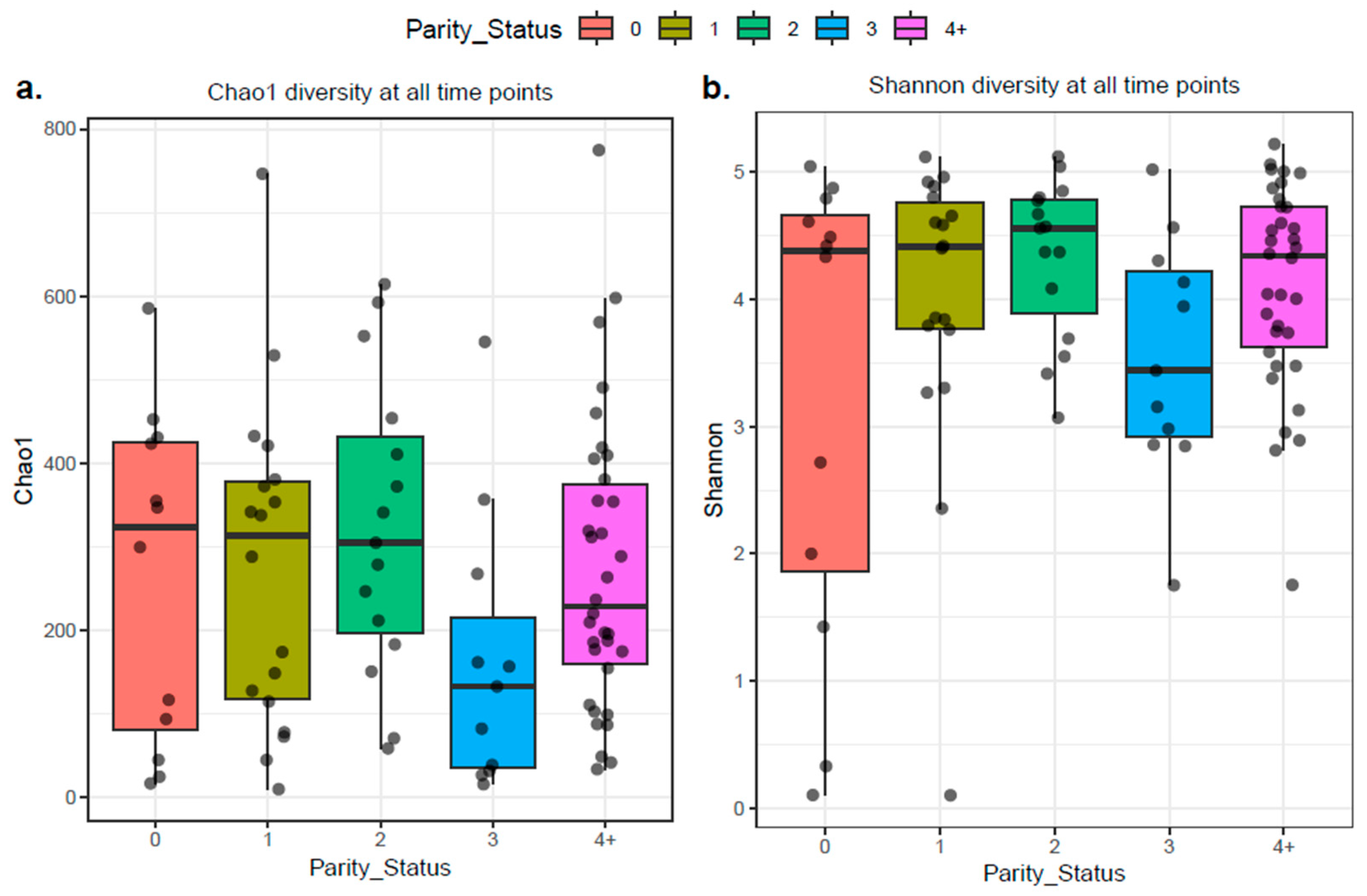

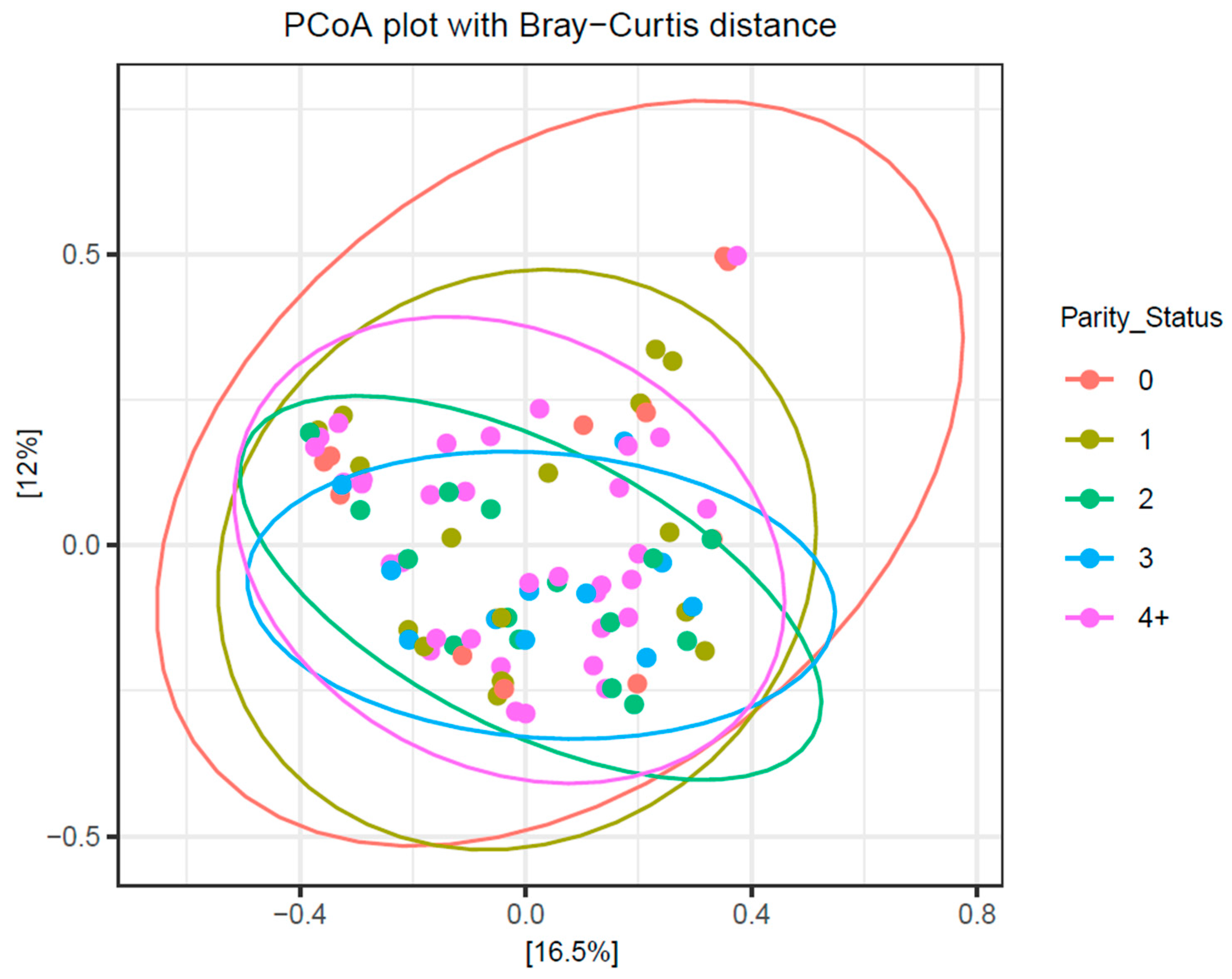

2.5. Parity and the Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. DNA Extraction

4.4. Preparation of DNA for Sequencing

4.5. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCT | Dry cow therapy |

| NOAB | No Antibiotics |

| CEF | Cephaguard |

| UBRORED | Ubro Red Dry Cow Intramammary Suspension |

References

- McGrath, B.A.; Fox, P.F.; McSweeney, P.L.; Kelly, A.L. Composition and properties of bovine colostrum: A review. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016, 96, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, M.M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Younes, H.A.; Abdel-Hamid, M.; Romeih, E.; Mehanni, A.-H.E.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Chen, W.; Zhang, N. An updated and comprehensive review on the composition and preservation strategies of bovine colostrum and its contributions to animal health. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 291, 115379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, R.J.; Weiser, M.J. Bovine colostrum: Its constituents and uses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.G.; Silva, S.R.; Pereira, A.M.; Cerqueira, J.L.; Conceição, C. A Comprehensive Review of Bovine Colostrum Components and Selected Aspects Regarding Their Impact on Neonatal Calf Physiology. Animals 2024, 14, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppel, K.; Gołębiewski, M.; Grodkowski, G.; Slósarz, J.; Kunowska-Slósarz, M.; Solarczyk, P.; Łukasiewicz, M.; Balcerak, M.; Przysucha, T. Composition and Factors Affecting Quality of Bovine Colostrum: A Review. Animals 2019, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Goi, A.; Penasa, M.; Nardino, G.; Posenato, L.; De Marchi, M. Variation of immunoglobulins G, A, and M and bovine serum albumin concentration in Holstein cow colostrum. Animal 2021, 15, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelwagen, K.; Carpenter, E.; Haigh, B.; Hodgkinson, A.; Wheeler, T. Immune components of bovine colostrum and milk. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Duman, H.; Yalçıntaş, Y.M.; Canbolat, A.A.; Kalkan, A.E.; Karav, S.; Šamec, D. Antimicrobial Properties of Colostrum and Milk. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammon, H.M.; Liermann, W.; Frieten, D.; Koch, C. Review: Importance of colostrum supply and milk feeding intensity on gastrointestinal and systemic development in calves. Animal 2020, 14, s133–s143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelo, A.; Cullens, F.; Hanes, A.; Brester, J.L. Impact of 2 Versus 1 Colostrum Meals on Failure of Transfer of Passive Immunity, Pre-Weaning Morbidity and Mortality, and Performance of Dairy Calves in a Large Dairy Herd. Animals 2021, 11, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, S.; Roshan, M.; Ghoreishi, S.M.; Akhlaghi, A.; Kanani, M.; Abedi Shams-Abadi, A.R.; Ghaffari, M.H. Extended colostrum feeding for 2 weeks improves growth performance and reduces the susceptibility to diarrhea and pneumonia in neonatal Holstein dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8130–8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzchowski, G.; Miciński, J.; Wójcik, R.; Nowakowski, J. Colostrum-supplemented transition milk positively affects serum biochemical parameters, humoral immunity indicators and the growth performance of calves. Livest. Sci. 2020, 234, 103976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.; Ashfield, A.; Earley, B.; Welsh, M.; Gordon, A.; Morrison, S.J. Evaluation of factors associated with immunoglobulin G, fat, protein, and lactose concentrations in bovine colostrum and colostrum management practices in grassland-based dairy systems in Northern Ireland. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, D.M.; Tyler, J.W.; VanMetre, D.C.; Hostetler, D.E.; Barrington, G.M. Passive Transfer of Colostral Immunoglobulins in Calves. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2000, 14, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zou, Y.; Wu, Z.H.; Li, S.L.; Cao, Z.J. Colostrum quality affects immune system establishment and intestinal development of neonatal calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 7153–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hese, I.; Goossens, K.; Ampe, B.; Haegeman, A.; Opsomer, G. Exploring the microbial composition of Holstein Friesian and Belgian Blue colostrum in relation to the transfer of passive immunity. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7623–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, F.; Fischer-Tlustos, A.; Neves, A.; He, Z.; Steele, M.; Guan, L. Metagenomic analysis revealed the individualized shift in ileal microbiome of neonatal calves in response to delaying the first colostrum feeding. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8783–8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.J.; Gleeson, D.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D. Impacts of Seasonal Housing and Teat Preparation on Raw Milk Microbiota: A High-Throughput Sequencing Study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 83, e02694-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, S.A.; Hernandez, L.L.; Skarlupka, J.H.; Suen, G.; Walker, T.M.; Ruegg, P.L. Influence of sampling technique and bedding type on the milk microbiota: Results of a pilot study. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6346–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, P.L. The bovine milk microbiome—An evolving science. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2022, 79, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.F.; Tanca, A.; Uzzau, S.; Oikonomou, G.; Bicalho, R.C.; Moroni, P. The bovine milk microbiota: Insights and perspectives from -omics studies. Mol. Biosyst. 2016, 12, 2359–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, G.; Addis, M.F.; Chassard, C.; Nader-Macias, M.E.F.; Grant, I.; Delbès, C.; Bogni, C.I.; Le Loir, Y.; Even, S. Milk Microbiota: What Are We Exactly Talking About? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainard, P. Mammary microbiota of dairy ruminants: Fact or fiction? Vet. Res. 2017, 48, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messman, R.D.; Lemley, C.O. Bovine neonatal microbiome origins: A review of proposed microbial community presence from conception to colostrum. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 7, txad057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Al-Zahrani, I.A.; Khan, R.; Soliman, S.A.; Turkistani, S.A.; Alawi, M.; Azhar, E.I. Microbiological risk assessment and resistome analysis from shotgun metagenomics of bovine colostrum microbiome. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 31, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.C.; Malcata, F.X.; Silva, C.C.G. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Raw-Milk Cheeses: From Starter Cultures to Probiotic Functions. Foods 2022, 11, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, B.; Moustafa, S.; Shata, R.; Sayed-Ahmed, M.Z.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Ali, M.S.; Alam, N.; Ahmad, S.; Kasem, N.; Elbaz, E.; et al. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Dairy Cattle, Milk, Environment, and Workers’ Hands. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Tiwari, R.; Gugjoo, M.B.; Yatoo, M.I.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Karthik, K.; Khurana, S.K.; Singh, R.; et al. Advances in therapeutic and managemental approaches of bovine mastitis: A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2021, 41, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.I.; Cappato, L.P.; Guimarães, J.T.; Balthazar, C.F.; Rocha, R.S.; Franco, L.T.; da Cruz, A.G.; Corassin, C.H.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. Listeria monocytogenes in Milk: Occurrence and Recent Advances in Methods for Inactivation. Beverages 2019, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIreland. European Communities (Hygenic Production and Placing in the Market of Raw Milk, Heat-Treated Milk and Milk-Based Products) Regulations 1996; S.I. No. 9/1996. Irish Statute Book, 1996. Available online: https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1996/si/9 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Pantoja, J.C.F.; Hulland, C.; Ruegg, P.L. Dynamics of somatic cell counts and intramammary infections across the dry period. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 90, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppel, K.; Gołębiewski, M.; Grodkowski, G.; Solarczyk, P.; Kostusiak, P.; Klopčič, M.; Sakowski, T. Use of somatic cell count as an indicator of colostrum quality. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tang, G.; Guo, W.; Lei, J.; Yao, J.; Xu, X. Detection of the Core bacteria in colostrum and their association with the rectal microbiota and with Milk composition in two dairy cow farms. Animals 2021, 11, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.d.; Silva, J.T.d.; Santos, F.H.d.R.; Bittar, C.M.M. Nutritional and microbiological quality of bovine colostrum samples in Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Zootec. 2017, 46, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, K.M.; Conrad, E.; Lago, A.; Campbell, J.; Quigley, J.; Tyler, H. Nationwide evaluation of quality and composition of colostrum on dairy farms in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3997–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, S.; Ghorbani, G.R.; Khorvash, M.; Martin, O.B.; Mahdavi, A.H.; Riasi, A. The impact of season, parity, and volume of colostrum on Holstein dairy cows colostrum composition. Agric. Sci. 2017, 8, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, H.; Okuyucu, I.C. Non-genetic factors affecting some colostrum quality traits in Holstein cattle. Pak. J. Zool. 2020, 52, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalera-Moreno, N.; Serrano-Perez, B.; Molina, E.; López de Armentia Osés, L.; Sanz, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, J. Maternal nutrition carry-over effects on beef cow colostrum but not on milk fatty acid composition. In Proceedings of the EAAP-74th Annual Meeting, Lyon, France, 26 August–1 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D.-A.; Posastiuc, F.P.; Constantin, N.T.; Andrei, C.R.; Marian, F.; Codreanu, M.D. The Impact of Parity on Dairy Cows Colostrum Quality. Cluj Vet. J. 2024, 29, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, L.D.; Ellinger, D.K. Colostral Immunoglobulin Concentrations Among Breeds of Dairy Cattle1. J. Dairy Sci. 1981, 64, 1727–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehoe, S.I.; Jayarao, B.M.; Heinrichs, A.J. A Survey of Bovine Colostrum Composition and Colostrum Management Practices on Pennsylvania Dairy Farms1. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4108–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zentrich, E.; Iwersen, M.; Wiedrich, M.C.; Drillich, M.; Klein-Jöbstl, D. Short communication: Effect of barn climate and management-related factors on bovine colostrum quality. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 7453–7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-del-Río, N.; Rolle, D.; García-Muñoz, A.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, S.; Valldecabres, A.; Lago, A.; Pandey, P. Colostrum immunoglobulin G concentration of multiparous Jersey cows at first and second milking is associated with parity, colostrum yield, and time of first milking, and can be estimated with Brix refractometry. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 5774–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.F.; Teixeira, A.G.; Lima, F.S.; Ganda, E.K.; Higgins, C.H.; Oikonomou, G.; Bicalho, R.C. The bovine colostrum microbiome and its association with clinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Miao, R.; Tao, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Qu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Qu, Y. Longitudinal Changes in Milk Microorganisms in the First Two Months of Lactation of Primiparous and Multiparous Cows. Animals 2023, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispie, F.; Flynn, J.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; Meaney, W.J. Dry cow therapy with a non-antibiotic intramammary teat seal—A review. Ir. Vet. J. 2004, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Parliament; The Council of the European Union. Regulation (Eu) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on veterinary medicinal products and repealing Directive 2001/82/EC. Document 32019R0006. 2019. L4. pp. 43–167. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/6/oj (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Hommels, N.M.C.; Ferreira, F.C.; van den Borne, B.H.P.; Hogeveen, H. Antibiotic use and potential economic impact of implementing selective dry cow therapy in large US dairies. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8931–8946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, F.C.; Martínez-López, B.; Okello, E. Potential impacts to antibiotics use around the dry period if selective dry cow therapy is adopted by dairy herds: An example of the western US. Prev. Vet. Med. 2022, 206, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhorne, C.; Gupta, S.D.; Horsman, S.; Wood, C.; Wood, B.J.; Barker, L.; Deutscher, A.; Price, R.; McGowan, M.R.; Humphris, M.; et al. Bacterial culture and antimicrobial susceptibility results from bovine milk samples submitted to four veterinary diagnostic laboratories in Australia from 2015 to 2019. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1232048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, P.; Żółkiewski, P.; Januś, E. A Review on Mastitis in Dairy Cows Research: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhagen, B.A.; Köster, G.; Wallmann, J.; Heuwieser, W. Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and their resistance against antimicrobial agents in dairy cows in Brandenburg, Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2542–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awandkar, S.P.; Kulkarni, M.B.; Khode, N.V. Bacteria from bovine clinical mastitis showed multiple drug resistance. Vet. Res. Commun. 2022, 46, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, E.; ElAshmawy, W.R.; Williams, D.R.; Lehenbauer, T.W.; Aly, S.S. Effect of dry cow therapy on antimicrobial resistance of mastitis pathogens post-calving. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1132810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Grimaud, G.; Linehan, K.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Microbiota and Resistome Analysis of Colostrum and Milk from Dairy Cows Treated with and without Dry Cow Therapies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, M.N.; Istiaq, A.; Clement, R.A.; Gibson, K.M.; Saha, O.; Islam, O.K.; Abir, R.A.; Sultana, M.; Siddiki, A.Z.; Crandall, K.A.; et al. Insights Into the Resistome of Bovine Clinical Mastitis Microbiome, a Key Factor in Disease Complication. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uí Chearbhaill, A.; Boloña, P.S.; Ryan, E.G.; McAloon, C.I.; Burrell, A.; McAloon, C.G.; Upton, J. Survey of farm, parlour and milking management, parlour technologies, SCC control strategies and farmer demographics on Irish dairy farms. Ir. Vet. J. 2024, 77, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (IBEC), D.I.I. Irish Dairy Industry Economic & Social Snapshot. Available online: https://www.ibec.ie/dairyindustryireland/our-dairy-story/economics-and-social (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Central Statistics Office (CSO). Statistical Yearbook of Ireland: Part 3 Travel, Agriculture, Environment and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-syi/statisticalyearbookofireland2021part3/agri/dairyfarming/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Alugongo, G.M.; Li, S.; Cao, Z. Bovine milk microbiota: Key players, origins, and potential contributions to early-life gut development. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 59, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huey, S.; Kavanagh, M.; Regan, A.; Dean, M.; McKernan, C.; McCoy, F.; Ryan, E.G.; Caballero-Villalobos, J.; McAloon, C.I. Engaging with selective dry cow therapy: Understanding the barriers and facilitators perceived by Irish farmers. Ir. Vet. J. 2021, 74, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, M.; Loor, J.J.; Elolimy, A.; Li, L.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Yin, S.; Qu, Y. Analysis of Cow-Calf Microbiome Transfer Routes and Microbiome Diversity in the Newborn Holstein Dairy Calf Hindgut. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 736270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, A.; Nydam, D.; Foditsch, C.; Warnick, L.; Wolfe, C.; Doster, E.; Morley, P.S. Characterization and comparison of the microbiomes and resistomes of colostrum from selectively treated dry cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.-L.; Zhang, G.; Gao, H.-H.; Deng, K.-X.; Chu, Y.-F.; Wu, D.-Y.; Yan, S.-Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, J. Analysis of bovine colostrum microbiota at a dairy farm in Ningxia, China. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 119, 104984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, R.S.; Silva e Silva, L.C.; de Souza, M.R.; Reis, R.B.; da Silva, P.C.L.; Lacorte, G.A.; Nicoli, J.R.; Neumann, E.; Nunes, Á.C. Changes in bovine milk bacterial microbiome from healthy and subclinical mastitis affected animals of the Girolando, Gyr, Guzera, and Holstein breeds. Int. Microbiol. 2022, 25, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippone Pavesi, L.; Pollera, C.; Sala, G.; Cremonesi, P.; Monistero, V.; Biscarini, F.; Bronzo, V. Effect of the Selective Dry Cow Therapy on Udder Health and Milk Microbiota. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowski, Ł.; Powierska-Czarny, J.; Wolko, Ł.; Piotrowska-Cyplik, A.; Cyplik, P.; Czarny, J. The influence of bacteria causing subclinical mastitis on the structure of the cow’s milk microbiome. Molecules 2022, 27, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.F.; Bicalho, M.L.d.S.; Bicalho, R.C. Evaluation of milk sample fractions for characterization of milk microbiota from healthy and clinical mastitis cows. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, B.P.T.; Wredle, E.; Dicksved, J. Analysis of the developing gut microbiota in young dairy calves—Impact of colostrum microbiota and gut disturbances. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 53, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Istiaq, A.; Clement, R.A.; Sultana, M.; Crandall, K.A.; Siddiki, A.Z.; Hossain, M.A. Metagenomic deep sequencing reveals association of microbiome signature with functional biases in bovine mastitis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaglia, E.C.R.; Gomes, M.S.; Canisso, I.F.; Zhou, Z.; Lima, S.F.; Rall, V.L.M.; Oikonomou, G.; Bicalho, R.C.; Lima, F.S. Milk microbiome and bacterial load following dry cow therapy without antibiotics in dairy cows with healthy mammary gland. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, D.; Ide, H.; Osaki, M.; Sekizaki, T. Identification of Facklamia sourekii from a lactating cow. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2006, 68, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.J.; Sabour, P.M.; Gong, J.; Yu, H.; Leslie, K.E.; Griffiths, M.W. Characterization of bacterial populations recovered from the teat canals of lactating dairy and beef cattle by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006, 56, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, H.; Fehr, K.B.; Sepehri, S.; Francoz, D.; De Buck, J.; Barkema, H.W.; Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E. Invited review: Microbiota of the bovine udder: Contributing factors and potential implications for udder health and mastitis susceptibility. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 10605–10625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrah, A.; Callegaro, S.; Pakroo, S.; Finocchiaro, R.; Giacomini, A.; Corich, V.; Cassandro, M. New insights into the raw milk microbiota diversity from animals with a different genetic predisposition for feed efficiency and resilience to mastitis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, E.V.; Staib, L.; Huptas, C.; Scherer, S.; Wenning, M. Facklamia lactis sp. nov., isolated from raw milk. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, I.; Gryaznova, M.; Smirnova, Y.; Morozova, P.; Mikhalev, V.; Zimnikov, V.; Latsigina, I.; Shabunin, S.; Mikhailov, E.; Syromyatnikov, M. Association of milk microbiome with bovine mastitis before and after antibiotic therapy. Vet. World 2023, 16, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Istiaq, A.; Rahman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Anwar, A.; Siddiki, A.M.A.M.Z.; Sultana, M.; Crandall, K.A.; Hossain, M.A. Microbiome dynamics and genomic determinants of bovine mastitis. Genomics 2020, 112, 5188–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-H.; Lee, K.-C.; Weiss, N.; Kang, K.; Park, Y.-H. Jeotgalicoccus halotolerans gen. nov., sp. nov. and Jeotgalicoccus psychrophilus sp. nov., isolated from the traditional Korean fermented seafood jeotgal. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.; Klug, K.; Frischmann, A.; Busse, H.-J.; Kämpfer, P.; Jäckel, U. Jeotgalicoccus coquinae sp. nov. and Jeotgalicoccus aerolatus sp. nov., isolated from poultry houses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadioti, A.; Azhar, E.I.; Bibi, F.; Jiman-Fatani, A.; Aboushoushah, S.M.; Yasir, M.; Raoult, D.; Angelakis, E. ‘Jeotgalicoccus saudimassiliensis’ sp. nov., a new bacterial species isolated from air samples in the urban environment of Makkah, Saudi Arabia. New Microbes New Infect. 2017, 15, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyles, L.; Collins, M.D.; Foster, G.; Falsen, E.; Schumann, P. Jeotgalicoccus pinnipedialis sp. nov., from a southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Shi, J.X.; Xiao, H.D.; Tang, S.K.; Liu, Z.X.; Huang, K.; Cui, X.L.; Li, W.J. Jeotgalicoccus marinus sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from a sea urchin. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.-Q.; Li, R.; Zheng, L.-Q.; Lin, D.-Q.; Sun, J.-Q.; Li, S.-P.; Li, W.-J.; Jiang, J. Jeotgalicoccus huakuii sp. nov., a halotolerant bacterium isolated from seaside soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 60, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callon, C.; Duthoit, F.; Delbès, C.; Ferrand, M.; Le Frileux, Y.; De Crémoux, R.; Montel, M.-C. Stability of microbial communities in goat milk during a lactation year: Molecular approaches. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 30, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, V.; Gillespie, A.; Ganda, E.; Evans, N.J.; Carter, S.D.; Lenzi, L.; Lucaci, A.; Haldenby, S.; Barden, M.; Griffiths, B.E.; et al. The bovine foot skin microbiota is associated with host genotype and the development of infectious digital dermatitis lesions. Microbiome 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Sangalli, E.; Facchi, M.; Fontana, F.; Mancabelli, L.; Donofrio, G.; Ventura, M. Metataxonomic analysis of milk microbiota in the bovine subclinical mastitis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Amit; Jamwal, R. Isolation and identification of Jeotgalicoccus sp. CR2 and evaluation of its resistance towards heavy metals. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, S.; Fursova, K.; Shulcheva, I.; Nikanova, D.; Artyemieva, O.; Kolodina, E.; Sorokin, A.; Dzhelyadin, T.; Shchannikova, M.; Shepelyakovskaya, A.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Milk Microbiomes and Their Association with Bovine Mastitis in Two Farms in Central Russia. Animals 2021, 11, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidlund, J.; Deressa Gelalcha, B.; Swanson, S.; costa Fahrenholz, I.; Deason, C.; Downes, C.; Kerro Dego, O. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Control, and Prevention of Bovine Staphylococcal Mastitis. In Mastitis in Dairy Cattle, Sheep and Goats; Kerro Dego, O., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Taponen, S.; Björkroth, J.; Pyörälä, S. Coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from bovine extramammary sites and intramammary infections in a single dairy herd. J. Dairy Res. 2008, 75, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, R.; Hess, C.; Urbantke, V.; Wittek, T.; Baumgartner, M. Characterization of Staphylococcus Species Isolated from Bovine Quarter Milk Samples. Animals 2019, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Visscher, A.; Supré, K.; Haesebrouck, F.; Zadoks, R.N.; Piessens, V.; Van Coillie, E.; Piepers, S.; De Vliegher, S. Further evidence for the existence of environmental and host-associated species of coagulase-negative staphylococci in dairy cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 172, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, H.; Plaizier, J.C.; De Buck, J.; Barkema, H.W.; Khafipour, E. Composition of the teat canal and intramammary microbiota of dairy cows subjected to antimicrobial dry cow therapy and internal teat sealant. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 10191–10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergestad, M.E.; Touzain, F.; De Vliegher, S.; De Visscher, A.; Thiry, D.; Ngassam Tchamba, C.; Mainil, J.G.; L’Abee-Lund, T.; Blanchard, Y.; Wasteson, Y. Whole Genome Sequencing of Staphylococci Isolated From Bovine Milk Samples. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 715851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, V.K.C.; Costa, G.M.d.; Guimarães, A.S.; Heinemann, M.B.; Lage, A.P.; Dorneles, E.M.S. Relationship between virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.L.; Tomazi, T.; Barreiro, J.R.; Beuron, D.C.; Arcari, M.A.; Lee, S.H.I.; Martins, C.M.d.M.R.; Junior, J.P.A.; dos Santos, M.V. Effects of bovine subclinical mastitis caused by Corynebacterium spp. on somatic cell count, milk yield and composition by comparing contralateral quarters. Vet. J. 2016, 209, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücken, A.; Wente, N.; Zhang, Y.; Woudstra, S.; Krömker, V. Corynebacteria in bovine quarter milk samples—Species and somatic cell counts. Pathogens 2021, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, L.; O’Sullivan, O.; Stanton, C.; Beresford, T.P.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D. The complex microbiota of raw milk. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 664–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremonesi, P.; Ceccarani, C.; Curone, G.; Severgnini, M.; Pollera, C.; Bronzo, V.; Riva, F.; Addis, M.F.; Filipe, J.; Amadori, M.; et al. Milk microbiome diversity and bacterial group prevalence in a comparison between healthy Holstein Friesian and Rendena cows. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikoloudaki, O.; Lemos Junior, W.J.F.; Borruso, L.; Campanaro, S.; De Angelis, M.; Vogel, R.F.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. How multiple farming conditions correlate with the composition of the raw cow’s milk lactic microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 1702–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floris, I.; Battistini, R.; Tramuta, C.; Garcia-Vozmediano, A.; Musolino, N.; Scardino, G.; Masotti, C.; Brusa, B.; Orusa, R.; Serracca, L.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Lactic Acid Bacteria from Dairy Products in Northern Italy. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez, A.B.; Campedelli, I.; Delgado, S.; Alegría, Á.; Salvetti, E.; Felis, G.E.; Mayo, B.; Torriani, S. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles of Dairy Leuconostoc, Analysis of the Genetic Basis of Atypical Resistances and Transfer of Genes In Vitro and in a Food Matrix. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleshkova, T.; Bazukyan, I.; Papadimitriou, K.; Gotcheva, V.; Angelov, A.; Dimov, S.G. Exploring the Multifaceted Genus Acinetobacter: The Facts, the Concerns and the Oppoptunities the Dualistic Geuns Acinetobacter. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2411043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.M.A.; Abd-Elhafeez, H.H.; Al-Jabr, O.A.; El-Zamkan, M.A. Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii Isolated from Raw Milk. Biology 2022, 11, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, P.; Higgins, P.G.; Schaubmar, A.R.; Failing, K.; Leidner, U.; Seifert, H.; Scheufen, S.; Semmler, T.; Ewers, C. Seasonal Occurrence and Carbapenem Susceptibility of Bovine Acinetobacter baumannii in Germany. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, A.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, M.; Nam, H.; Tamang, M.; Chae, M.; Jang, G.; Jung, S.; Lim, S. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Acinetobacter from raw bulk tank milk in Korea. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1997–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.; Saavedra, M.J.; Henriques, M. Bovine mastitis disease/pathogenicity: Evidence of the potential role of microbial biofilms. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, P.; Cao, H.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, T. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Bovine Mastitis in Northern Jiangsu Province and Correlation to Drug Resistance and Biofilm Formability. Animals 2024, 14, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.N.; Han, S.G. Bovine mastitis: Risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1699–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Xie, X.; Bao, H.; Sun, L.; He, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wei, R.; et al. Insights Into the Bovine Milk Microbiota in Dairy Farms with Different Incidence Rates of Subclinical Mastitis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, G.; Bicalho, M.L.; Meira, E.; Rossi, R.E.; Foditsch, C.; Machado, V.S.; Teixeira, A.G.; Santisteban, C.; Schukken, Y.H.; Bicalho, R.C. Microbiota of cow’s milk; distinguishing healthy, sub-clinically and clinically diseased quarters. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, E.K.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Lima, S.F.; Kronauer, K.; Decter, D.H.; Oikonomou, G.; Schukken, Y.H.; Bicalho, R.C. Longitudinal metagenomic profiling of bovine milk to assess the impact of intramammary treatment using a third-generation cephalosporin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, E.K.; Gaeta, N.; Sipka, A.; Pomeroy, B.; Oikonomou, G.; Schukken, Y.H.; Bicalho, R.C. Normal milk microbiome is reestablished following experimental infection with Escherichia coli independent of intramammary antibiotic treatment with a third-generation cephalosporin in bovines. Microbiome 2017, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.; Kabera, F.; Dufour, S.; Godden, S.; Roy, J.-P.; Nydam, D. Selective dry-cow therapy can be implemented successfully in cows of all milk production levels. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkens, Z.; Piepers, S.; De Vliegher, S. Impact of Selective Dry Cow Therapy on Antimicrobial Consumption, Udder Health, Milk Yield, and Culling Hazard in Commercial Dairy Herds. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, A.; Craig, A.L.; Gordon, A.W.; Ferris, C.P. Impact of adopting non-antibiotic dry-cow therapy on the performance and udder health of dairy cows. Vet. Rec. 2022, 190, e1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Warda, A.K.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Non-antibiotic microbial solutions for bovine mastitis–live biotherapeutics, bacteriophage, and phage lysins. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 45, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostermann, K.; Crispie, F.; Flynn, J.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C.; Meaney, W. Intramammary infusion of a live culture of Lactococcus lactis for treatment of bovine mastitis: Comparison with antibiotic treatment in field trials. J. Dairy Res. 2008, 75, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispie, F.; Alonso-Gómez, M.; O’Loughlin, C.; Klostermann, K.; Flynn, J.; Arkins, S.; Meaney, W.; Paul Ross, R.; Hill, C. Intramammary infusion of a live culture for treatment of bovine mastitis: Effect of live lactococci on the mammary immune response. J. Dairy Res. 2008, 75, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecher, C.; Daly, M.; Berry, D.P.; Klostermann, K.; Flynn, J.; Meaney, W.; Hill, C.; McCarthy, T.V.; Ross, R.P.; Giblin, L. Administration of a live culture of Lactococcus lactis DPC 3147 into the bovine mammary gland stimulates the local host immune response, particularly IL-1beta and IL-8 gene expression. J. Dairy Res. 2009, 76, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ren, Y.; Xi, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H. A Novel Lactobacilli-Based Teat Disinfectant for Improving Bacterial Communities in the Milks of Cow Teats with Subclinical Mastitis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, P.M.; Smith, B.S.; Stewart, W.K.; Gonzalez, R.N.; Rubino, S.D.; Gusik, S.A.; Kulisek, E.S.; Projan, S.J.; Blackburn, P. Evaluation of a Nisin-Based Germicidal Formulation on Teat Skin of Live Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 3185–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.P.; Flynn, J.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; Meaney, W.J. The Natural Food Grade Inhibitor, Lacticin 3147, Reduced the Incidence of Mastitis After Experimental Challenge with Streptococcus dysgalactiae in Nonlactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 2108–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, D.P.; Wheelock, A.I.; Flynn, J.; Meaney, W.J.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Protection Against Staphylococcus aureus Mastitis in Dairy Cows Using a Bismuth-Based Teat Seal Containing the Bacteriocin, Lacticin 3147. J. Dairy Sci. 2000, 83, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispie, F.; Twomey, D.; Flynn, J.; Hill, C.; Ross, P.; Meaney, W. The lantibiotic lacticin 3147 produced in a milk-based medium improves the efficacy of a bismuth-based teat seal in cattle deliberately infected with Staphylococcus aureus. J. Dairy Res. 2005, 72, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klostermann, K.; Crispie, F.; Flynn, J.; Meaney, W.J.; Paul Ross, R.; Hill, C. Efficacy of a teat dip containing the bacteriocin lacticin 3147 to eliminate Gram-positive pathogens associated with bovine mastitis. J. Dairy Res. 2010, 77, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Hu, S.; Cao, L. Therapeutic effect of nisin Z on subclinical mastitis in lactating cows. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3131–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touza-Otero, L.; Landin, M.; Diaz-Rodriguez, P. Fighting antibiotic resistance in the local management of bovine mastitis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 115967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, Z.; Radinović, M.; Čabarkapa, I.; Kladar, N.; Božin, B. Natural Agents against Bovine Mastitis Pathogens. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Youn, H.-Y.; Moon, J.-S.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.-H. Comparative anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activities of postbiotics derived from kefir and normal raw milk lactic acid bacteria against bovine mastitis pathogens. LWT 2024, 191, 115699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, L.; Forte, C.; D’Avino, N.; Pisano, R.; Hyatt, D.R.; Rueca, F.; Passamonti, F. Evaluation of Brix refractometer as an on-farm tool for colostrum IgG evaluation in Italian beef and dairy cattle. J. Dairy Res. 2021, 88, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, J.D.; Lago, A.; Chapman, C.; Erickson, P.; Polo, J. Evaluation of the Brix refractometer to estimate immunoglobulin G concentration in bovine colostrum. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisira, V.; Zigo, F.; Kadaši, M.; Klein, R.; Farkašová, Z.; Vargová, M.; Mudroň, P. Comparative Analysis of Methods for Somatic Cell Counting in Cow’s Milk and Relationship between Somatic Cell Count and Occurrence of Intramammary Bacteria. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, P.R.; Middleton, J.R. Laboratory Handbook on Bovine Mastitis; National Mastitis Council, Inc.: New Prague, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, K.E.; Fouhy, F.; CA, O.S.; Ryan, C.A.; Dempsey, E.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Effect of storage, temperature, and extraction kit on the phylogenetic composition detected in the human milk microbiota. Microbiologyopen 2021, 10, e1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Value | Coef (β) | SE | p-Value | q-Value | N | N.Not.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterium | Ubro Red | 1.327 | 0.494 | 0.0086 | 0.0251 | 90 | 89 |

| Facklamia | Ubro Red | 1.360 | 0.566 | 0.0184 | 0.0462 | 90 | 86 |

| Jeotgaliococcus | Ubro Red | 1.580 | 0.584 | 0.0082 | 0.0241 | 90 | 86 |

| Leuconostoc | Cefquinome | 3.766 | 1.231 | 0.0029 | 0.0099 | 90 | 43 |

| Staphylococcus | Cefquinome | 3.002 | 0.857 | 0.0007 | 0.0030 | 90 | 72 |

| Staphylococcus | Ubro Red | 2.546 | 0.851 | 0.0036 | 0.0115 | 90 | 72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conboy-Stephenson, R.; Patangia, D.; Linehan, K.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum as Influenced by Antibiotic Treatment. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121217

Conboy-Stephenson R, Patangia D, Linehan K, Ross RP, Stanton C. The Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum as Influenced by Antibiotic Treatment. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121217

Chicago/Turabian StyleConboy-Stephenson, Ruth, Dhrati Patangia, Kevin Linehan, R. Paul Ross, and Catherine Stanton. 2025. "The Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum as Influenced by Antibiotic Treatment" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121217

APA StyleConboy-Stephenson, R., Patangia, D., Linehan, K., Ross, R. P., & Stanton, C. (2025). The Microbial Composition of Bovine Colostrum as Influenced by Antibiotic Treatment. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121217