Phage Therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: A Review on Advances in Classification, Applications, and Translational Roadblocks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Drug Options for the Treatment of A. baumannii in Clinical Practice

2.1. Drug Resistance Mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii

2.2. Treatment of CRAB

2.3. Treatment of Carbapenem-Susceptible A. baumannii

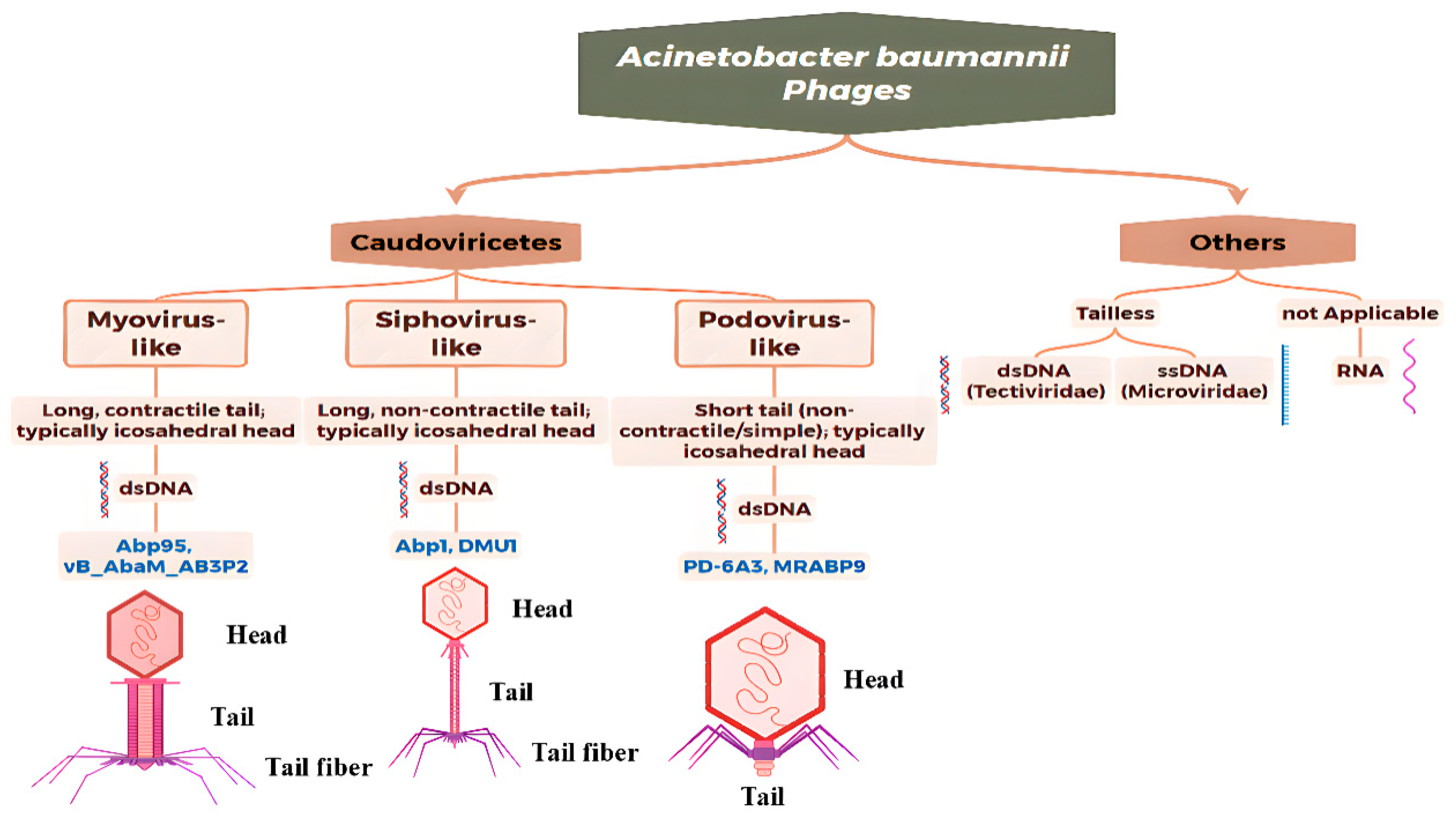

3. Morphological, Genomics and Taxonomy of A. baumannii Phages

3.1. Overview of Modern Genomics-Based Taxonomy

3.1.1. Myovirus-like Phages

3.1.2. Siphovirus-like Phages

3.1.3. Podovirus-like Phages

3.2. Development of Taxonomic Basis and Crucial Genomic Characteristics

3.3. Challenges and Trends

3.4. Bacteriophage Resistance Mechanism of A. baumannii

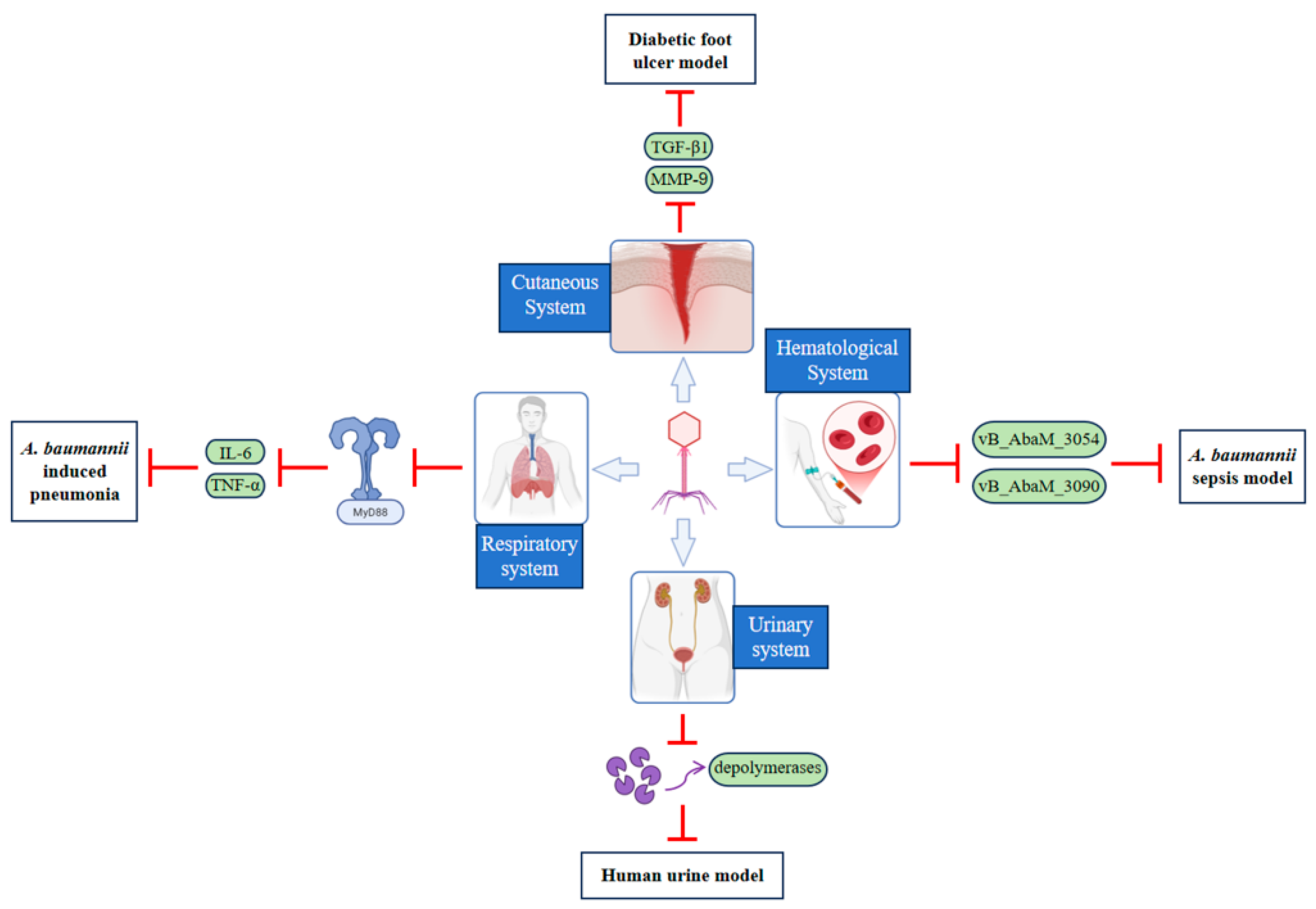

4. Application of Phages in the Treatment of A. baumannii Infections

4.1. Advances in In Vitro Research

4.2. Advances in In Vivo and Clinical Research

4.2.1. Respiratory System

4.2.2. Cutaneous System

4.2.3. Hematological System

4.2.4. Urinary System

4.2.5. Preventing Hospital-Acquired Transmission

4.2.6. Application in the Detection of Antimicrobial-Resistant A. baumannii

4.3. Route of Administration

4.3.1. Topical Administration

4.3.2. Systemic Administration

4.4. Challenges and Limitations

5. Genetically Engineered Bacteriophages

5.1. Renovation Objectives and Key Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Technology Type | Technical Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Key Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Approaches (BRED method [137], Chemical Mutagenesis, Transduction) | Inducing mutagenesis via chemical agents or transferring exogenous genes via phages | Simple operation, minimal equipment requirements | High randomness, low efficiency, imprecise regulation; non-target mutations | Reliance on random mutagenesis; lacks directed modification capability; fundamentally distinct from modern precise editing |

| CRISPR-Cas Precision Editing [138] | Utilizing CRISPR-Cas systems for site-specific genomic modification (e.g., knockout, insertion, replacement) | High precision and efficiency for targeted gene modification; high editing efficiency and reproducibility | Off-target effects, potential for altered host tropism or enhanced virulence; requires comprehensive genomic data | Core of precise targeting; overcomes randomness of traditional methods; limited by understanding of gene function |

| HDR-Mediated Scarless Editing [139] | Removing exogenous marker sequences to ensure genomic integrity | Enhanced biosafety by avoiding risks from exogenous DNA | Complex operation, demanding experimental conditions | Focus on biosafety optimization; complements (e.g., CRISPR) rather than replaces existing editors |

| Modular Design with Standardized Biological Parts (BioBricks) [140] | Modularizing functional genes for rapid prototyping via standardized assembly | Streamlines processes and enhances reproducibility for accelerated translation; facilitates functional expansion | Potential module incompatibility issues; underdeveloped standardized parts libraries | Core of standardization & modularization; enhances efficiency & operability; facilitates technology transfer |

| Total Genome Synthesis and Rebooting [141] | De novo chemical synthesis or refactoring of genomes for customized functions | Overcoming natural genomic constraints for customizable functional modules; enables novel antimicrobial mechanisms | High synthesis costs, technically challenging; error-prone in long assembly | Shift from modifying existing to de novo design; overcomes functional limits of natural phages; highest technical barrier |

5.2. Engineering Technology

5.3. Challenges and Safety

5.3.1. Immune Recognition and Altered Pharmacokinetics

5.3.2. Engineered Vectors for Horizontal Gene Transfer

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, B.A.; Hamouda, A.; Amyes, S.G. The rise of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawad, A.; Seifert, H.; Snelling, A.M.; Heritage, J.; Hawkey, P.M. Survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces: Comparison of outbreak and sporadic isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 1938–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, V.K.; Wallace, L.; Smith, L.S. Disinfection of Acinetobacter baumannii-contaminated surfaces relevant to medical treatment facilities with ultraviolet C light. Mil. Med. 2007, 172, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, L. Death report of OXA-143-lactamase prodsuperbug. Autops. Case Rep. 2019, 9, e2019106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.T.; Hwee, J.; Song, C.; Tan, B.K.; Chong, S.J. Burns infection profile of Singapore: Prevalence of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and the role of blood cultures. Burn. Trauma 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, L.; Gibson, K.E.; Horcher, A.; Prenovost, K.; McNamara, S.E.; Foxman, B.; Kaye, K.S.; Bradley, S. Prevalence of and risk factors for multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii colonization among high-risk nursing home residents. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, D.; Chang, J.; Lu, S.; Xu, J.; Hu, P.; Zhang, K.; Sun, X.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Analysis of virulence proteins in pathogenic Acinetobacter baumannii to provide early warning of zoonotic risk. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 266, 127222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-R.; Tan, J.J.-Y.; Chen, C.-W.; Huang, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-Y.; Goh, B.H.; Tsai, K.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Mong, K.-K.T. Synthesis of Acinetobacter baumannii Lipid A(s) and derivatives and their structure-immunostimulatory activity relationships. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B.S.; Kinsella, R.L.; Harding, C.M.; Feldman, M.F. The Secrets of Acinetobacter Secretion. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, H.W.; Talbot, G.H.; Bradley, J.S.; Edwards, J.E.; Gilbert, D.; Rice, L.B.; Scheld, M.; Spellberg, B.; Bartlett, J. Bad Bugs, No Drugs: No ESKAPE! An Update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T.; Kuhl, S.J.; Blasdel, B.G.; Kutter, E.M. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Lu, H.; Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Q. Phages against Pathogenic Bacterial Biofilms and Biofilm-Based Infections: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febvre, H.P.; Rao, S.; Gindin, M.; Goodwin, N.D.M.; Finer, E.; Vivanco, J.S.; Lu, S.; Manter, D.K.; Wallace, T.C.; Weir, T.L. PHAGE Study: Effects of Supplemental Bacteriophage Intake on Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.C.T.; Friman, V.-P.; Smith, M.C.M.; Brockhurst, M.A. Resistance Evolution against Phage Combinations Depends on the Timing and Order of Exposure. mBio 2019, 10, e01652-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, F.G.; Forsyth, J.H.; Patwa, R.; Kostoulias, X.; Trim, M.; Subedi, D.; Archer, S.K.; Morris, F.C.; Oliveira, C.; Kielty, L.; et al. Bacteriophage-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii are resensitized to antimicrobials. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aziz, A.M.A.; Elgaml, A.; Ali, Y.M. Bacteriophage Therapy Increases Complement-Mediated Lysis of Bacteria and Enhances Bacterial Clearance After Acute Lung Infection With Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veesler, D.; Cambillau, C. A common evolutionary origin for tailed-bacteriophage functional modules and bacterial machineries. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.-L.; Mahmud, S.A.; Selvaprakash, K.; Lin, N.-T.; Chen, Y.-C. Tail Fiber Protein-Immobilized Magnetic Nanoparticle-Based Affinity Approaches for Detection of Acinetobacter baumannii. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10335–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, L.; Bleriot, I.; de Aledo, M.G.; Fernández-García, L.; Pacios, O.; Oliveira, H.; López, M.; Ortiz-Cartagena, C.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; Pascual, Á.; et al. Development of an Anti-Acinetobacter baumannii Biofilm Phage Cocktail: Genomic Adaptation to the Host. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0192321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Park, J.-H.; Yong, D. Efficacy of bacteriophage treatment against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Galleria mellonella larvae and a mouse model of acute pneumonia. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wienhold, S.-M.; Brack, M.C.; Nouailles, G.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Korf, I.H.E.; Seitz, C.; Wienecke, S.; Dietert, K.; Gurtner, C.; Kershaw, O.; et al. Preclinical Assessment of Bacteriophage Therapy against Experimental Acinetobacter baumannii Lung Infection. Viruses 2021, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, B.; Xu, L.; Cong, C.; Murtaza, B.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Xu, M.; Yin, J.; et al. In vivo efficacy of phage cocktails against carbapenem resistance Acinetobacter baumannii in the rat pneumonia model. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0046724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koncz, M.; Stirling, T.; Mehdi, H.H.; Méhi, O.; Eszenyi, B.; Asbóth, A.; Apjok, G.; Tóth, Á.; Orosz, L.; Vásárhelyi, B.M.; et al. Genomic surveillance as a scalable framework for precision phage therapy against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Cell 2024, 187, 5901–5918.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Courtwright, A.M.; Koval, C.; Lehman, S.M.; Morales, S.; Furr, C.L.; Rosas, F.; Brownstein, M.J.; Fackler, J.R.; Sisson, B.M.; et al. Early clinical experience of bacteriophage therapy in 3 lung transplant recipients. Am. J. Transpl. 2019, 19, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsea, J.; Uyttebroek, S.; Chen, B.; Wagemans, J.; Lood, C.; Van Gerven, L.; Spriet, I.; Devolder, D.; Debaveye, Y.; Depypere, M.; et al. Bacteriophage Therapy for Difficult-to-Treat Infections: The Implementation of a Multidisciplinary Phage Task Force (The PHAGEFORCE Study Protocol. Viruses 2021, 13, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, S.; Huang, G. Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteriophage: Progress in Isolation, Genome Sequencing, Preclinical Re-search, and Clinical Application. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquet, M.; Lohou, E.; Pair, E.; Sonnet, P.; Mullié, C. Efflux Pump Overexpression Profiling in Acinetobacter baumannii and Study of New 1-(1-Naphthylmethyl)-Piperazine Analogs as Potential Efflux Inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0071021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Ergün, T.; İzGördü, Ö.K.; Darcan, C.; Avci, H.; Öztürk, B.; Güner, H.R.; Ghorbanpoor, H.; Güzel, F.D. Revealing the single-channel characteristics of OprD (OccAB1) porins from hospital strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur. Biophys. J. 2023, 52, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikhani, Z.; Nazari, R.; Rostami, M.N. First report of OXA-143-lactamase producing Acinetobacter baumannii in Qom, Iran. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2017, 20, 1282–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P.G.; Wisplinghoff, H.; Stefanik, D.; Seifert, H. Selection of topoisomerase mutations and overexpression of adeB mRNA transcripts during an outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 821–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.; Vadlamudi, G.; Newton, D.; Foxman, B.; Xi, C. The influence of biofilm formation and multidrug resistance on environmental survival of clinical and environmental isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016, 44, e65–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; A Bonomo, R. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghali, A.; Coyne, A.J.K.; Caniff, K.; Bleick, C.; Rybak, M.J. Sulbactam-durlobactam: A novel β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combination targeting carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Pharmacotherapy 2023, 43, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Réville, T.F.; Guler, S.; Comita-Prevoir, J.; Chen, B.; Bifulco, N.; Huynh, H.; Lahiri, S.; Shapiro, A.B.; McLeod, S.M.; Carter, N.M.; et al. ETX2514 is a broad-spectrum β-lactamase inhibitor for the treatment of drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria including Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S.M.; Moussa, S.H.; Hackel, M.A.; Miller, A.A. In Vitro Activity of Sulbactam-Durlobactam against Acinetobacter bamannii-calcoaceticus Complex Isolates Collected Globally in 2016 and 2017. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02534-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, D.; Petinaki, E.; Tsolaki, V.; Manoulakas, E.; Mantzarlis, K.; Apostolopoulou, O.; Sfyras, D.; Zakynthinos, E. Colistin versus Colistin Combined with Ampicillin-Sulbactam for Multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Treatment: An Open-label Prospective Study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 22, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbain, J.; Peleg, A.Y. Treatment of Acinetobacter infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannot, K.; Bolard, A.; Plésiat, P. Resistance to polymyxins in Gram-negative organisms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 49, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheetz, M.H.; Qi, C.; Warren, J.R.; Postelnick, M.J.; Zembower, T.; Obias, A.; Noskin, G.A. In vitro activities of various antimicrobials alone and in combination with tigecycline against carbapenem-intermediate or -resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.; Berens, C.; Projan, S.J.; Hillen, W. Comparison of tetracycline and tigecycline binding to ribosomes mapped by dimethyl-sulphate and drug-directed Fe2+ cleavage of 16S rRNA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 53, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-A.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lu, P.-L.; Chen, H.-C.; Chang, H.-L.; Sheu, C.-C. Antibiotic strategies and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 908.e1–908.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, B.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Kuo, S.-C.; Liu, P.-Y.; Fung, C.-P. Efficacy of tigecycline for secondary Acinetobacter bacteremia and factors associated with treatment failure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3637–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, W.; Xiao, Y. Comparison of Tigecycline or Cefoperazone/Sulbactam therapy for bloodstream infection due to Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, S.L.; Scott, L.J. Intravenous Minocycline: A Review in Acinetobacter Infections. Drugs 2016, 76, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, C.J.; Garzia, C.; Uhlemann, A.-C. Acinetobacter baumannii treatment strategies: A review of therapeutic challenges and considerations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0106324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T.P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Carrara, E.; Retamar, P.; Tängdén, T.; Bitterman, R.; Bonomo, R.A.; de Waele, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Akova, M.; Harbarth, S.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European society of intensive care medicine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellison, T.K.; McKinnon, P.S.; Rybak, M.J. Epidemiology, resistance, and outcomes of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia treated with imipenem-cilastatin or ampicillin-sulbactam. Pharmacotherapy 2001, 21, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, C.; Segal-Maurer, S.; Rahal, J.J. Considerations in control and treatment of nosocomial infections due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.; Al-Saryi, N.; Al-Kadmy, I.M.S.; Aziz, S.N. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as an emerging concern in hospitals. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 6987–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakil, W.H.; Rizk, S.S.; El-Halawany, A.M.; Rateb, M.E.; Attia, A.S. Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections in the United Kingdom versus Egypt: Trends and Potential Natural Products Solutions. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Kumar, A. Bacteriophage therapeutics to confront multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii—A global health menace. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2022, 14, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Lundborg, C.S.; Sun, X.; Zhu, N.; Gu, S.; Dong, H. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in China: A national level estimate for inpatients. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2021, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P. The Bacteriophage Head-to-Tail Interface. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 88, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Amann, R.I.; Bardy, P.; Bartlau, N.; Barylski, J.; Błażejak, S.; Bouzari, M.; Briegel, A.; Briers, Y.; et al. Summary of taxonomy changes ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) from the Bacterial Viruses Subcommittee, 2025. J. Gen. Virol. 2025, 106, 002111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.K.; Sistrom, M.; Wertz, J.E.; Kortright, K.E.; Narayan, D.; Turner, P.E. Phage selection restores antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.L.; Davis, C.M.; Harris, G.; Zhou, H.; Rather, P.N.; Hrapovic, S.; Lam, E.; Dennis, J.J.; Chen, W. Characterization of Virulent T4-Like Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteriophages DLP1 and DLP2. Viruses 2023, 15, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, S.; Jiang, L.; Tan, J.; Yan, X.; Gou, C.; Chen, X.; Xiang, L.; Wang, D.; Huang, G.; et al. Characterisation and sequencing of the novel phage Abp95, which is effective against multi-genotypes of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Han, K.; Chen, L.; Luo, S.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Biological characterization and genomic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii phage BUCT628. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; You, X.; Liu, X.; Fei, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, R.; Li, Y. Characterization of phage HZY2308 against Acinetobacter baumannii and identification of phage-resistant bacteria. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, S.; Shin, M.; Kim, J. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effects of Phage vB_AbaSi_W9 and Antibiotics against Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Su, J.; Luo, D.; Liang, B.; Liu, S.; Zeng, H. Isolation and genome-wide analysis of the novel Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophage vB_AbaM_AB3P2. Arch. Virol. 2024, 169, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardiana, M.; Teh, S.-H.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Yang, H.-H.; Lin, L.-C.; Lin, N.-T. Characterization of a novel and active temperate phage vB_AbaM_ABMM1 with antibacterial activity against Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Hua, X.; Yu, Y.; Leptihn, S.; Loh, B. Therapeutic evaluation of the Acinetobacter baumannii phage Phab24 for clinical use. Virus Res. 2022, 320, 198889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusradze, I.; Karumidze, N.; Rigvava, S.; Dvalidze, T.; Katsitadze, M.; Amiranashvili, I.; Goderdzishvili, M. Characterization and Testing the Efficiency of Acinetobacter baumannii Phage vB-GEC_Ab-M-G7 as an Antibacterial Agent. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, S.; Shin, M.; Kim, J. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Bacteriophages to Target Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Le, S.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhang, L.; Yao, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, F. Characterization and genome sequencing of phage Abp1, a new phiKMV-like virus infecting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 66, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehde, B.M.; Niewohner, D.; Keomanivong, F.E.; Carruthers, M.D. Genome Sequence and Characterization of Acinetobacter Phage DMU1. PHAGE 2021, 2, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, S.; Sabouri, S.; Tadjrobehkar, O.; Samareh, A.; Niaz, H.; Sanjari, N.; Hosseini-Nave, H.; Skurnik, M. Characterization of bacteriophage vB_AbaS_SA1 and its synergistic effects with antibiotics against clinical multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Pathog. Dis. 2024, 82, ftae028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hu, K.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mu, D.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, D.; Shi, Y. A Novel Phage PD-6A3, and Its Endolysin Ply6A3, With Extended Lytic Activity Against Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Y.; You, H.; Shen, Y.; Miao, F.; Yuan, C.; Chen, X.; Zhai, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, J. Characterization and therapeutic potential of MRABP9, a novel lytic bacteriophage infecting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strains. Virology 2024, 595, 110098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leungtongkam, U.; Kitti, T.; Khongfak, S.; Thummeepak, R.; Tasanapak, K.; Wongwigkarn, J.; Khanthawong, S.; Belkhiri, A.; Ribeiro, H.G.; Turner, J.S.; et al. Genome characterization of the novel lytic phage vB_AbaAut_ChT04 and the antimicrobial activity of its lysin peptide against Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from different time periods. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Shkoporov, A.N.; Lood, C.; Millard, A.D.; Dutilh, B.E.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; van Zyl, L.J.; Aziz, R.K.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M.; et al. Abolishment of morphology-based taxa and change to binomial species names: 2022 taxonomy update of the ICTV bacterial viruses subcommittee. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, A.V.; Lavysh, D.G.; Klimuk, E.I.; Edelstein, M.V.; Bogun, A.G.; Shneider, M.M.; Goncharov, A.E.; Leonov, S.V.; Severinov, K.V. Novel Fri1-like Viruses Infecting Acinetobacter baumannii-vB_AbaP_AS11 and vB_AbaP_AS12-Characterization, Comparative Genomic Analysis, and Host-Recognition Strategy. Viruses 2017, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfull, G.F. All the world’s a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2523344122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.E.; Wu, X.; Hall, L.R.; Lawrence, D.; Molleston, J.M.; Schriefer, L.A.; Droit, L.; Weagley, J.S.; Olson, B.S.; Rimmer, J.; et al. Single cell viral tagging of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii reveals rare bacteriophages omitted by other techniques. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2526719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Mahbub, N.U.; Shin, W.S.; Oh, M.H. Phage-encoded depolymerases as a strategy for combating multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1462620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, M.; Imperi, F.; Artuso, I.; Capecchi, G.; Spagnoli, C.; Visaggio, D.; Rampioni, G.; Leoni, L.; Visca, P. Phage-mediated colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Drug Resist. Update 2024, 73, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlman, S.; Avellaneda-Franco, L.; Rutten, E.L.; Gulliver, E.L.; Solari, S.; Chonwerawong, M.; Kett, C.; Subedi, D.; Young, R.B.; Campbell, N.; et al. Isolation, engineering and ecology of temperate phages from the human gut. Nature 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Pu, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Song, L.; Li, M.; An, X.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Acinetobacter baumannii Phages: Past, Present and Future. Viruses 2023, 15, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Cury, J.; Yoon, E.-J.; Krizova, L.; Cerqueira, G.C.; Murphy, C.; Feldgarden, M.; Wortman, J.; Clermont, D.; Lambert, T.; et al. The genomic diversification of the whole Acinetobacter genus: Origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 2866–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.C.; Reyneke, B.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Phage-antibiotic synergy to combat multidrug resistant strains of Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, L.R.; Laub, M.T.E. coli prophages encode an arsenal of defense systems to protect against temperate phages. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1004–1018.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bondy-Denomy, J. Anti-CRISPRs Go Viral: The Infection Biology of CRISPR-Cas Inhibitors. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Rodriguez, T.M.; Hollister, E.B. Unraveling the viral dark matter through viral metagenomics. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1005107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabrouk, A.S.; Ongenae, V.; Claessen, D.; Brenzinger, S.; Briegel, A. A Flexible and Efficient Microfluidics Platform for the Characterization and Isolation of Novel Bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0159622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tan, X.; Xiong, M.; Lu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Zhou, C.; Wei, S.; et al. Efficacy of precisely tailored phage cocktails targeting carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii reveals evolutionary trade-offs: A proof-of-concept study. EBioMedicine 2025, 120, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhong, S.; Shi, Q.; Zheng, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Huang, Z.; An, D.; Xu, H.; et al. An activator regulates the DNA damage response and anti-phage defense networks in Moraxellaceae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, S.; Ruotsalainen, P.; Jalasvuori, M. On-Demand Isolation of Bacteriophages Against Drug-Resistant Bacteria for Personalized Phage Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulakvelidze, A.; Alavidze, Z.; Morris, J.G., Jr. Bacteriophage Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, H.N.; Hafidh, R.R.; Abdulamir, A.S. Formation of therapeutic phage cocktail and endolysin to highly multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: In vitro and in vivo study. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regeimbal, J.M.; Jacobs, A.C.; Corey, B.W.; Henry, M.S.; Thompson, M.G.; Pavlicek, R.L.; Quinones, J.; Hannah, R.M.; Ghebremedhin, M.; Crane, N.J.; et al. Personalized Therapeutic Cocktail of Wild Environmental Phages Rescues Mice from Acinetobacter baumannii Wound Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5806–5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, C.D. When does 2 plus 2 equal 5? A review of antimicrobial synergy testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4124–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, S.J.; Samson, J.E.; Moineau, S. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Barceló, C.; Hochberg, M.E. Evolutionary Rationale for Phages as Complements of Antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyejobi, G.K.; Xiong, D.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Xue, H.; Ogolla, F.; Wei, H. Genetic Signatures from Adaptation of Bacteria to Lytic Phage Identify Potential Agents To Aid Phage Killing of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e0059321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, F.L.G.; Kostoulias, X.; Subedi, D.; Korneev, D.; Peleg, A.Y.; Barr, J.J. Phage-antibiotic combination is a superior treat-ment against Acinetobacter baumannii in a preclinical study. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Ochoa, A.K.; González-Gómez, J.P.; Quiñones, B.; Campo, N.C.-D.; Valdez-Torres, J.B.; Chaidez-Quiroz, C. Bacteriophage Indie resensitizes multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii to antibiotics in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulssico, J.; PapukashvilI, I.; Espinosa, L.; Gandon, S.; Ansaldi, M. Phage-antibiotic synergy: Cell filamentation is a key driver of successful phage predation. PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Ryu, S. Bacteriophage PBC1 and its endolysin as an antimicrobial agent against Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, B.M.; Tam, V.H. Case Commentary: Novel Therapy for Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0199621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peifen, C.; Yingjun, K.; Si, W.; Xiaowen, G.; Yang, Z.; Xin, T.; Yingfei, M.; Hongzhou, L. A case report of phage therapy against lung infection caused by Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Electron. J. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.; Dai, J.; Guo, M.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Qu, H.; Lu, H.; Jin, J.; et al. Pre-optimized phage therapy on secondary Acinetobacter baumannii infection in four critical COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili, M.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Verbeken, G.; Chanishvili, N.; Tediashvili, M.; Lashkhi, N.; Glonti, T.; Krylov, V.; Mast, J.; Van Parys, L.; et al. Quality-controlled small-scale production of a well-defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaswamy, V.C.; Kalasuramath, S.B.; Sadanand, C.K.; Basavaraju, A.K.; Ginnavaram, V.; Bille, S.; Ukken, S.S.; Pushparaj, U.N. Ability of bacteriophage in resolving wound infection caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in uncontrolled diabetic rats. Microb. Drug Resist. 2015, 21, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili, M.; Monserez, R.; van Belleghem, J.; Rose, T.; Jennes, S.; De Vos, D.; Verbeken, G.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Pirnay, J.-P. Stability of bacteriophages in burn wound care products. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, T.L.; Rhode, S.; Munoz, P.; Simon, K.; Krüttgen, A.; Stoppe, C.; Ruhl, T.; Beier, J.P.; Horz, H.-P.; Kim, B.-S. Antiseptic management of critical wounds: Differential bacterial response upon exposure to antiseptics and first insights into antiseptic/phage interactions. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 5374–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplessis, C.A.; Biswas, B. A Review of Topical Phage Therapy for Chronically Infected Wounds and Preparations for a Randomized Adaptive Clinical Trial Evaluating Topical Phage Therapy in Chronically Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshkasheli, L.; Kutateladze, M.; Balarjishvili, N.; Bolkvadze, D.; Save, J.; Oechslin, F.; Que, Y.-A.; Resch, G. Efficacy of newly isolated and highly potent bacteriophages in a mouse model of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 19, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Chen, K.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Ying, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, S.; Huang, Z.; Gao, R.; et al. Evaluation of the impact of repeated intravenous phage doses on mammalian host–phage interactions. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0135923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagińska, N.; Cieślik, M.; Górski, A.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E. The Role of Antibiotic Resistant A. baumannii in the Pathogenesis of Urinary Tract Infection and the Potential of Its Treatment with the Use of Bacteriophage Therapy. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygorcewicz, B.; Wojciuk, B.; Roszak, M.; Łubowska, N.; Błażejczak, P.; Jursa-Kulesza, J.; Rakoczy, R.; Masiuk, H.; Dołęgowska, B. Environmental Phage-Based Cocktail and Antibiotic Combination Effects on Acinetobacter baumannii Biofilm in a Human Urine Model. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, F.L.G.; Barr, J.J. Phage Therapy in the Postantibiotic Era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00066-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc-Carrillo, C.; Abedon, S.T. Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B.; Barlow, R.; D’Arcy, H.; Gillespie, B.; Sobel, J.D. Urinary tract infection: Self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann. Epidemiol. 2000, 10, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.-C.; Chen, B.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Huang, S.-H.; Chung, R.; Yu, P.-C.; Yu, C.-P. Epidemiological Survey of Enterovirus Infections in Taiwan From 2011 to 2020: Retrospective Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e59449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-H.; Tseng, C.-C.; Wang, L.-S.; Chen, Y.-T.; Ho, G.-J.; Lin, T.-Y.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chen, L.-K. Application of Bacteriophage-containing Aerosol against Nosocomial Transmission of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an Intensive Care Unit. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.; Elsayed, S.; Reid, O.; Winston, B.; Lindsay, R. Burn wound infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, L. [New progress in the treatment of chronic wound of diabetic foot]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2018, 32, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, R.; Murt, A. Epidemiology of urological infections: A global burden. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2669–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, P.E.; Richet, H. The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacconelli, E.; Cataldo, M.A.; Dancer, S.J.; De Angelis, G.; Falcone, M.; Frank, U.; Kahlmeter, G.; Pan, A.; Petrosillo, N.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; et al. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20 (Suppl. 1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, M.V.; Hartstein, A.I. Acinetobacter outbreaks, 1977–2000. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003, 24, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, R.B.; Shipovskov, S.; Ferapontova, E.E. Electrochemical Immuno- and Aptamer-Based Assays for Bacteria: Pros and Cons over Traditional Detection Schemes. Sensors 2020, 20, 5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Phipps-Todd, B.; McMahon, T.; Elmgren, C.L.; Lutze-Wallace, C.; Todd, Z.A.; Garcia, M.M. Development of a monoclonal antibody-based colony blot immunoassay for detection of thermotolerant Campylobacter species. J. Microbiol. Methods 2016, 130, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.M.; Lee, S.Y. Optical Biosensors for the Detection of Pathogenic Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Luo, S.; Wang, L.; Lu, S.; Fu, Z. Engineering Phage Tail Fiber Protein as a Wide-Spectrum Probe for Acinetobacter baumannii Strains with a Recognition Rate of 100. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 9610–9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, S.; Semler, D.D.; Goudie, A.D.; Lynch, K.H.; Matinkhoo, S.; Finlay, W.H.; Dennis, J.J.; Vehring, R. Respirable bacteriophages for the treatment of bacterial lung infections. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2013, 26, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooley, R.T.; Biswas, B.; Gill, J.J.; Hernandez-Morales, A.; Lancaster, J.; Lessor, L.; Barr, J.J.; Reed, S.L.; Rohwer, F.; Benler, S.; et al. Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00954-17, Erratum in Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02221-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.02221-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Banerjee, P.; Liu, Y.; Mi, Z.; Bai, C.; Hu, H.; To, K.K.; Duong, H.T.; Leung, S.S. Development of thermosensitive hydrogel wound dressing containing Acinetobacter baumannii phage against wound infections. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 602, 120508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, L.; Bax, R.; Clokie, M.; Dawson, M.; Fairhead, H.; Fischetti, V.A.; Foster, S.; Gilmore, B.F.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Harper, D.; et al. Alternatives to antibiotics—A pipeline portfolio review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehl, K.; Lemire, S.; Yang, A.C.; Ando, H.; Mimee, M.; Torres, M.D.T.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Lu, T.K. Engineering Phage Host-Range and Suppressing Bacterial Resistance through Phage Tail Fiber Mutagene-sis. Cell 2019, 179, 459–469.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, M.; Rupf, B.; Tala, M.; Qabrati, X.; Ernst, P.; Shen, Y.; Sumrall, E.; Heeb, L.; Plückthun, A.; Loessner, M.J.; et al. Reprogramming Bacteriophage Host Range through Structure-Guided Design of Chimeric Receptor Binding Proteins. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1336–1350.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Rollins, M.F.; Osuna, B.A.; Wiedenheft, B.; Bondy-Denomy, J. Bacteriophage Cooperation Suppresses CRISPR-Cas3 and Cas9 Immunity. Cell 2018, 174, 917–925.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Todeschini, T.C.; Wu, Y.; Kogay, R.; Naji, A.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Mondi, R.; Kaganovich, D.; Taylor, D.W.; Bravo, J.P.; et al. Kiwa is a membrane-embedded defense supercomplex activated at phage attachment sites. Cell 2025, 188, 5862–5877.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Ford, K.; Harris, K.; Gilmour, K.C.; Soothill, J.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Schooley, R.T.; et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, N.D.; Zhang, J.Y.; Borges, A.L.; Sousa, A.A.; Leon, L.M.; Rauch, B.J.; Walton, R.T.; Berry, J.D.; Joung, J.K.; Kleinstiver, B.P.; et al. Discovery of widespread type I and type V CRISPR-Cas inhibitors. Science 2018, 362, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcher, S.; Studer, P.; Muessner, C.; Klumpp, J.; Loessner, M.J. Cross-genus rebooting of custom-made, synthetic bacteriophage genomes in L-form bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Lemire, S.; Pires, D.P.; Lu, T.K. Engineering Modular Viral Scaffolds for Targeted Bacterial Population Editing. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaluru, N.; Muller, H.; Mitchell, L.A.; Ramalingam, S.; Stracquadanio, G.; Richardson, S.M.; Dymond, J.S.; Kuang, Z.; Scheifele, L.Z.; Cooper, E.M.; et al. Total synthesis of a functional designer eukaryotic chromosome. Science 2014, 344, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagens, S.; Habel, A.; von Ahsen, U.; von Gabain, A.; Bläsi, U. Therapy of experimental Pseudomonas infections with a nonreplicat ing genetically modified phage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3817–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, T.; Freeman, T.A.; Hilbert, D.W.; Duff, M.; Fuortes, M.; Stapleton, P.P.; Daly, J.M. Lysis-deficient bacteriophage therapy decreases endotoxin and inflammatory mediator release and improves survival in a murine peritonitis model. Surgery 2005, 137, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, A.M.; Fairhead, H.I. A commentary on the development of engineered phage as therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2095–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, A.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Węgrzyn, G.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B. Phage therapy: Current status and perspectives. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.D.; Dąbrowska, K.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Barr, J.J.; Bollyky, P.L. Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses 2018, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Cáceres, W.; Ye, M.; Balcázar, J.L. Bacteriophages as Environmental Reservoirs of Antibiotic Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigonyte, A.M.; Harrison, C.; MacDonald, P.R.; Montero-Blay, A.; Tridgett, M.; Duncan, J.; Sagona, A.P.; Constantinidou, C.; Jaramillo, A.; Millard, A. Comparison of CRISPR and Marker-Based Methods for the Engineering of Phage T7. Viruses 2020, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.L.; Gin, C.; Callahan, B.; Sheriff, E.K.; Duerkop, B.A.; Kleiner, M. Pseudo-pac site sequences used by phage P22 in generalized transduction of Salmonella. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2024.03.25.586692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Jaque, M.; Calero-Caceres, W.; Muniesa, M. Transfer of antibiotic-resistance genes via phage-related mobile elements. Plasmid 2015, 79, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Morphotype | Genus (Genomic Classification) | Representative Phages | Biological Characteristics and Genome | Host Range and Lytic Ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myovirus-like (Contractile tail with helical protein sheath; icosahedral capsid) | Phagecoctavirus | vB_AbaM-DLP_1,vB_AbaM-DLP_2 [57] | Elongated head; contractile tail with tail fibers; large burst size; short latency; stable over a broad pH range | Broad/unspecified range, high adaptability |

| Obolenskvirus | Abp95 [58] | Broad spectrum (29%; 58/200); short latency; high burst size; rapid adsorption rate; depolymerase-containing; effective against diverse sequence types of CRAB | Broad activity across CRAB sequence types | |

| vB-AbaM-IME-AB2, WCHABP1, WCHABP12, BUCT628 [59], and HZY2308 [60] | Genomically classified as Obolenskvirus. | Varies by phage | ||

| Unclassified | vB_AbaSi_W9 [61] | Broad host range; considered a potential therapeutic candidate despite lower lytic efficiency. | Broader than many myovirus-like phages | |

| vB_AbaM_AB3P2 [62] | Icosahedral head (70 nm diameter); tail 100 ± 10 nm long, 20 nm wide; potent lytic activity | Lytic only for A. baumannii strains AB3 & AB9; narrow host range | ||

| vB_AbaM_ABMM1 (mild bacteriophage) [63] | Lysogenic (genome integration); rapid adsorption; large burst size; stable at neutral pH and temperature; effective in vitro and in vivo | Broad/unspecified range | ||

| Phab24 [64], vB-GEC_Ab-M-G7 [65] and vB_AbaSi_W16 [66] | Morphologically and genetically similar to myovirus-like phages. | Varies by phage | ||

| Siphovirus-like (Long, non-contractile tail of unique morphology) | Friunavirus | Abp1 [67] | Standard icosahedral head; ~40–50 kb genome; encodes multiple biofilm penetration-associated genes | High specificity for host strain AB1; narrow host range |

| Unclassified | DMU1 [68] | Long, striated, flexible tail, terminating in tail spikes and/or fibers | Infects only A. baumannii ATCC19606 & ATCC17978 | |

| vB_AbaS_SA1 [69] | Latent period: 20 min; burst size: 250 PFU/cell; antibacterial efficacy against clinical MDR-AB | Targeting clinical multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains | ||

| Podovirus-like (Short, non-contractile tail) | Friunavirus | PD-6A3 [70] | Stable at 4–50 °C and pH 5–10; >90% adsorption within 5 min | Broad/unspecified range, high environmental adaptability |

| MRABP9 [71] | Short latent period; large burst size; significant anti-biofilm activity; inhibits bacterial regrowth; high environmental stability | Targeting clinical MDR A. baumannii strains | ||

| Unclassified | vB_AbaSi_W8 [61] | Lytic activity against clinical CRAB strains. | Narrower than vB_AbaSi_W9 | |

| vB_AbaAut_ChT04 [72] | Latent period: 10 min; burst size: 280 PFU/cell; infects 52 of 150 clinical MDR-AB strains | Covers ~34.7% of clinical MDR strains |

| Disease Type Treated | Study Model/Clinical Scenario | Key Phage(s)/Therapy | Core Efficacy & Characteristics | Limitations & Pending Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Diseases | Mouse pneumonia model [20,21], Rat pneumonia model [22]; Clinical VAP [101], lung abscess | Single phage, Phage cocktail therapy; Phage + Antibiotic combination | Clears CRAB strains in animal models, improves survival, alleviates inflammation; Adjunct to antibiotics aids patient recovery | Narrow phage host range [100], prone to inducing resistance; Mechanisms of immune system impact unclear |

| Skin Wounds | Burn wounds [104], Diabetic foot ulcers [105] (rat model & clinical cases) | Phage cocktail [104]; Phage + Topical care products [106]/Low-dose antiseptic [107] | Clears drug-resistant bacteria from wounds and promotes healing in animal models; Combined care enhances antibacterial effect clinically | Requires prior pathogen strain identification; Few clinical cases for diabetic wounds, lack of blinded trials [108] |

| Bacteremia or Sepsis | Mouse MDR A. baumannii sepsis model [109] | vB_AbaM_3054, vB_AbaM_3090 (alone or combined) [109] | Efficiently clears pathogens and significantly improves infection symptoms in animal models | Lack of clinical application reports; Human safety and efficacy need validation; Complex interactions with the host immune system [110] |

| Urinary Tract Infections | Human urine model, Animal models | Phage cocktail [111]; Phage+ Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole [112] | Inhibits biofilm formation in vitro [113], combination enhances antibacterial effect; No harm to normal flora [114] | High UTI recurrence rate requires optimized long-term regimen [115]; Insufficient clinical translation data |

| Hospital Transmission Control | ICU environment (CRAB contamination) [116] | Phage aerosol [117] | Reduces CRAB infection and resistance rates in ICU, aids environmental disinfection | Need to assess phage resistance development; Disinfection scope requires improvement [117] |

| Route Classification | Specific Method | Operational Procedure | Core Advantages | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical Administration | Nebulized Inhalation [128] | 1. Dilute phage stock with saline and administer via nebulizer [102]; 2. Use ultrasonic humidifier to aerosolize phage stock into saline, generating phage aerosol [117] | 1. Delivers phages directly to the respiratory tract, lysing lung infection strains; 2. Enables rapid disinfection of large areas, controlling nosocomial transmission | 1. Lung infections; 2. Disinfection of A. baumannii contamination in environments like ICUs |

| Local Wound Perfusion | Percutaneous catheter perfusion of phage cocktail into abscess cavities (e.g., pancreatic pseudocyst, gallbladder, abdominal abscess) [129] | 1. Acts directly on the infection site, increasing local phage concentration; 2. Reduces impact on other body areas, lowering adverse reaction risk | Diffuse drug-resistant A. baumannii infections | |

| Hydrogel Formulation | Mix polyethylene glycol castor oil P407, carbomer polymer C934P with phage suspension to prepare thermosensitive hydrogel [130] | 1. Maintains phage stability, enables sustained release; 2. Targets biofilms, extends antimicrobial duration | Chronic wound infections | |

| Systemic Administration | Intravenous Injection | Administer phage cocktail intravenously; can be combined with local administration [129] | 1. Rapid entry into systemic circulation, timely control of severe infections; 2. Synergizes with local administration, enhances comprehensiveness | Severe infections unresponsive to local treatment; Systemic disseminated A. baumannii infection |

| Aspect | Key Advantages | Key Risks & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting & Efficacy | Expanded host range via RBP engineering. Enhanced biofilm penetration (e.g., via depolymerase expression). Ability to target antibiotic-tolerant persister cells. | Potential for off-target activity due to altered host range. Unpredictable inflammatory responses at infection sites. |

| Pharmacokinetics | Extended serum half-life through capsid PEGylation. Potential for targeted delivery to specific tissues. | Risk of Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) upon repeated dosing. Complex and costly pharmacokinetic profiling. |

| Genetic Stability & Safety | CRISPR-mediated removal of virulence/lysogeny genes. Expression of anti-CRISPR proteins to overcome bacterial defenses. | Genetic instability during manufacturing/passage. Amplified potential for Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) of ARGs. Potential for off-target effects from gene editing. |

| Regulatory & Manufacturing | “Designer” phages with tailored functionalities. Potential for standardized, off-the-shelf products. | Immense regulatory hurdles for live, replicating biologics. Complex, costly, and scaled manufacturing requirements. Lack of long-term environmental impact data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liang, Y.; Xu, K.; Ye, Y.; He, M. Phage Therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: A Review on Advances in Classification, Applications, and Translational Roadblocks. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111134

Wang Y, Li L, Liang Y, Xu K, Ye Y, He M. Phage Therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: A Review on Advances in Classification, Applications, and Translational Roadblocks. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(11):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111134

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yilin, Liuyan Li, Yuqi Liang, Kehan Xu, Ying Ye, and Maozhang He. 2025. "Phage Therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: A Review on Advances in Classification, Applications, and Translational Roadblocks" Antibiotics 14, no. 11: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111134

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, L., Liang, Y., Xu, K., Ye, Y., & He, M. (2025). Phage Therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii Infections: A Review on Advances in Classification, Applications, and Translational Roadblocks. Antibiotics, 14(11), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111134