Exploring the Relationship Between Farmland Management and Manure-Derived Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Prevention and Control Strategies

Abstract

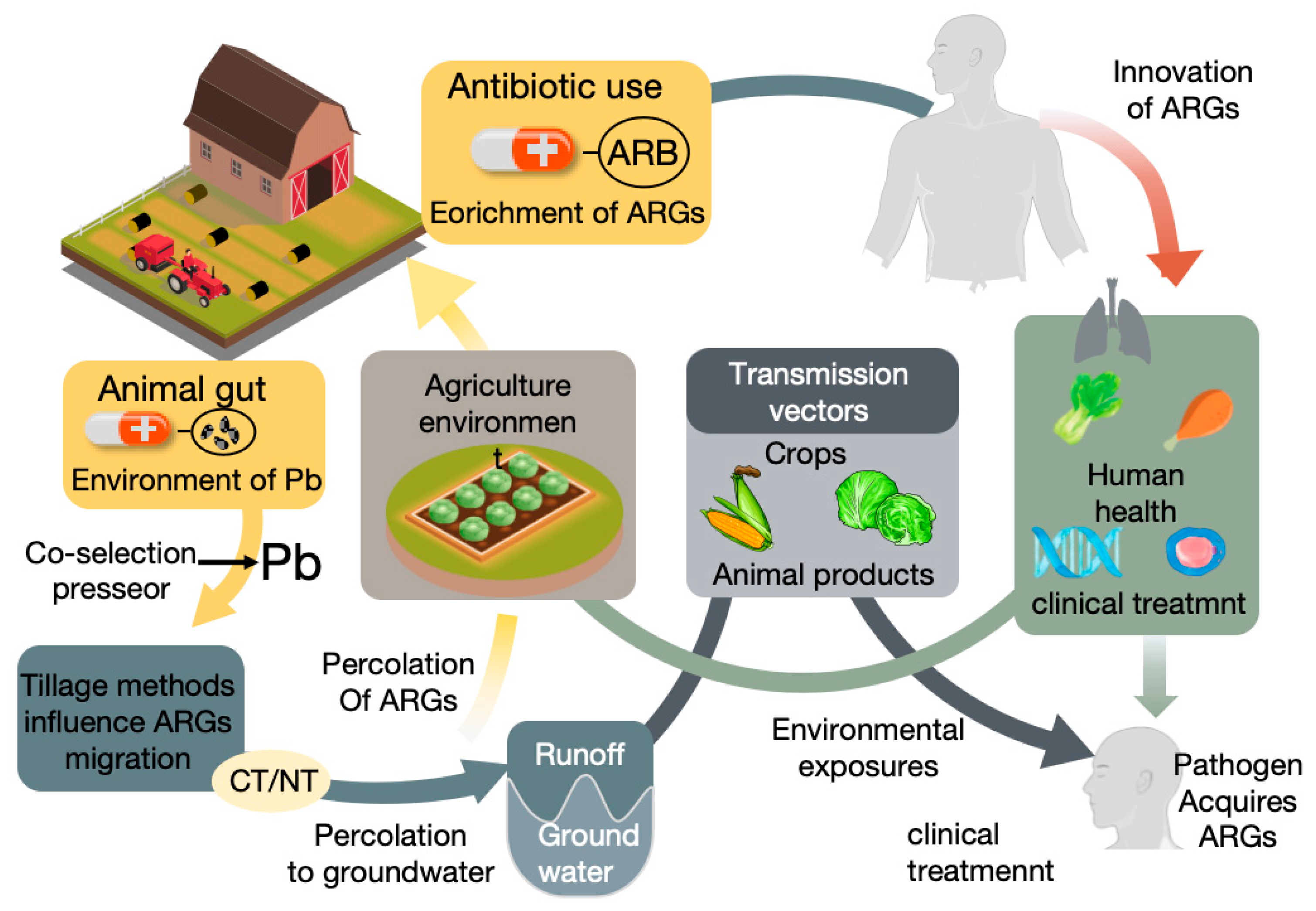

1. Introduction

2. Diversity and Risk of ARGs in Livestock Manure

2.1. Diversity of ARGs in Livestock Manure

2.2. Potential Risks of Manure-Derived ARGs

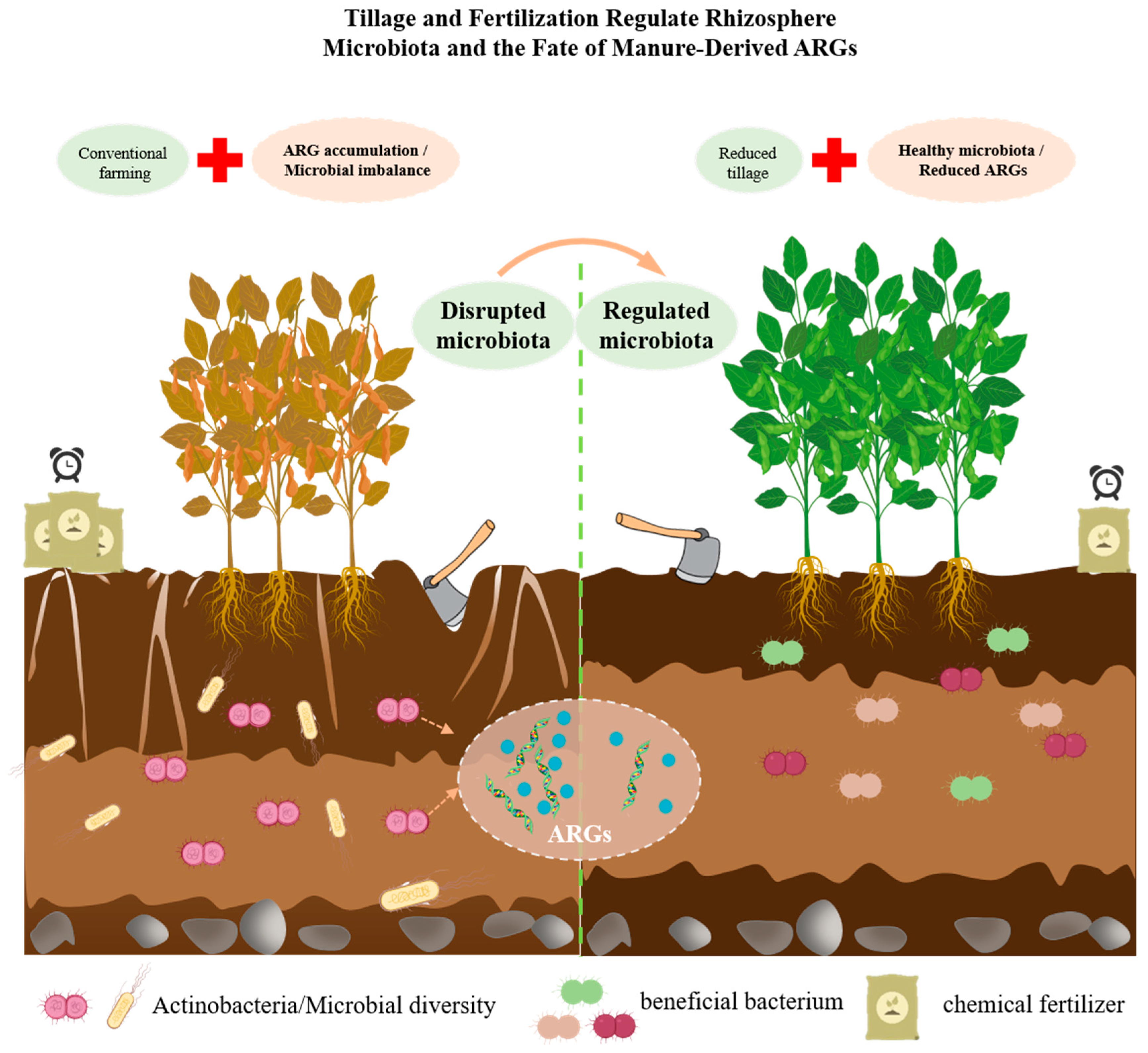

3. Influence of Tillage Mode on the Fate of ARGs in Manure-Amended Soils

3.1. Tillage-Induced Soil Structural Changes and Their Impact on ARG Fate

3.2. Tillage-Driven Microbial Community Restructuring and ARG Persistence Dynamics

3.3. Integrated Effects of Tillage–Manure–Soil Interactions on ARG Dynamics

| Cropping Modes | Provincial Regions | ARG Types | Abundance Levels | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat–maize rotation | Hebei Province | Multidrug, tetracycline, MLS, and other ARGs | Manure treatment ~2.6 × 105 (RPKM) > Chemical fertilizer treatment ~2.5 × 105 (RPKM) > No fertilizer control ~2.45 × 105 (RPKM) | [120] |

| Wheat monoculture | Jilin Province | tetA, tetC, tetG, sul1, sul2, intI1 | Relative abundance–Total abundance in control soil was ~0.45 (copies/16S rRNA) | [121] |

| Wheat–soybean rotation | Idaho, USA | sul1, sul2, tetW and other tetracycline, sulfonamide, and macrolide genes | Absolute abundance–Pig manure treatment: sul1 ~108, sul2 ~109, tetW ~108 (copies/g soil) | [66] |

| Rice–wheat rotation | Jiangsu Province | Total ARGs (especially multidrug resistance genes) | Relative abundance—Fallow treatment: ~1.5 × 108 (copies/g) rotation treatment: ~2.5 × 108 (copies/g) | [122] |

| Soya, Sunflower, Wheat | Rostov region, RUS | ermB, sul2, vanA | Relative abundance: 10−7–10−2 (copies/16S rRNA) | [123] |

| Wheat–Soybean intercropping | Anhui Province | tetA | Absolute abundance: Wheat: 5 × 104 (copies/g soil); Soybean: 103 (copies/g soil) | [124] |

| Eggplant–sweet pepper rotation | Daxing District, Beijing | 348 ARGs from 10 major classes | Relative abundance— OF: 0.06203 (copies/16S rRNA); MF: 0.05016 (copies/16S rRNA); IF: 0.04498 (copies/16S rRNA); CK: 0.01978 (copies/16S rRNA) | [9] |

| Maize–Wheat rotation | Hebei Province | 114 ARG subtypes, mainly multidrug, MLSB, aminoglycoside, β-lactam, and tetracycline classes | Relative abundance—M: 0.13; MN: 0.23 (copies/16S rRNA) | [21] |

| Corn | Lansing, Michigan (MI), USA | 89 ARG subtypes, mainly multidrug and tetracycline resistance | Relative abundance: abundance ranged from 0.016 to 0.043 (copies/16S rRNA) | [125] |

| Rice | Jiangxi Province | 144 ARGs subtypes and MGEs | Absolute abundance—no fertilizer: ~3 × 106 (copies/g); swine manure compost: ~6 × 106 | [126] |

| Soybean | Xinjiang Province | 289 ARGs subtypes, mainly multidrug and MLS | Relative abundance—plant-derived OMF ~0.046 (copies/cell); chicken manure ~0.052 (copies/cell) | [127] |

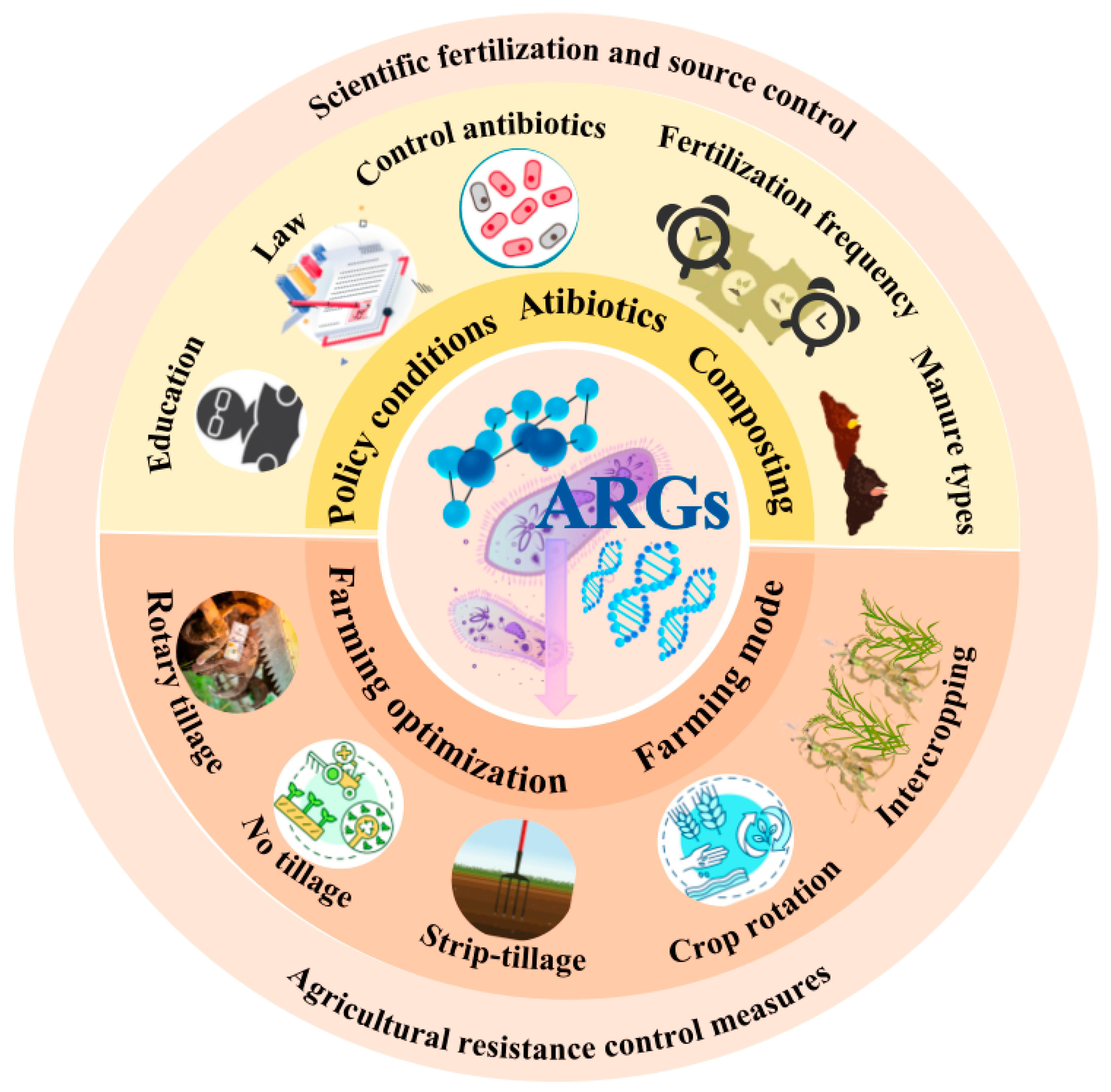

4. Fertilization Management Strategies and Their Impact on Soil ARG Profiles

4.1. Differential Effects of Fertilizer Types on ARG Accumulation

4.2. Effects of Fertilization Timing and Frequency on ARG Dynamics

5. Pesticide-Mediated Selection Pressure on Soil Resistome and Agricultural Systems

5.1. Pesticide Classes Differentially Modulate Soil ARG Profiles and Microbial Ecology

5.2. Dose-Dependent Effects of Pesticides on ARG Dissemination and Crop Performance

6. Coping Strategies and Future Perspectives

6.1. Coping Strategies: Mitigating ARG Spread in Agricultural Systems

6.2. Future Perspectives: Research Directions and Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.J.; Wellington, M.; Shah, R.M.; Ferreira, M.J. Antibiotic Stewardship in Food-producing Animals: Challenges, Progress, and Opportunities. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cycoń, M.; Mrozik, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Antibiotics in the Soil Environment—Degradation and Their Impact on Microbial Activity and Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yang, F.; Shen, S.; Mu, M.; Zhang, K. Effects of soil habitat changes on antibiotic resistance genes and related microbiomes in paddy fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 895, 165109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Shen, S.; Gao, W.; Ma, Y.; Han, B.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K. Deciphering discriminative antibiotic resistance genes and pathogens in agricultural soil following chemical and organic fertilizer. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Yang, F.; Tian, X.; Mu, M.; Zhang, K. Tracking antibiotic resistance gene transfer at all seasons from swine waste to receiving environments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 219, 112335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, T.; Domingues, S.; Da Silva, G.J. Manure as a Potential Hotspot for Antibiotic Resistance Dissemination by Horizontal Gene Transfer Events. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ashworth, A.J.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Durso, L.M.; Savin, M.; Cook, K.; Moore, P.A., Jr.; Owens, P.R. Antimicrobial resistant gene prevalence in soils due to animal manure deposition and long-term pasture management. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, C.; Shao, L. Diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in soils with four different fertilization treatments. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1291599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Peng, S.; Yang, X.; Hua, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X. Occurrence and human exposure risk of antibiotic resistance genes in tillage soils of dryland regions: A case study of northern Ningxia Plain, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Hughes, J.M. Critical Importance of a One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance. Ecohealth 2019, 16, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Kang, Q.; Du, T.; Cao, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wei, L.; Zhao, C.; He, L.; Du, X.-J.; Wang, S. Dual-mode biosensing platform for ultrasensitive Salmonella detection based on cascaded signal amplification coupled with DNA-functionalized Ag2S NPs@PB. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1472–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, P.; Lu, Z.; Mo, F.; Liao, Y.; Wen, X. Metagenomics reveals the abundance and accumulation trend of antibiotic resistance gene profile under long-term no tillage in a rainfed agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1238708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H.; Liu, H.; Zhu, A.; Khan, M.H.; Hussain, S.; Cao, H. Conservation tillage practices affect soil microbial diversity and composition in experimental fields. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1227297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, É.; Généreux, M.; Tremblay, M.; Rhouma, M.; Gasser, M.O.; Quessy, S.; Côté, C. Impact of liquid hog manure applications on antibiotic resistance genes concentration in soil and drainage water in field crops. Can. J. Microbiol. 2020, 66, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Yao, H. Effects of Composting Different Types of Organic Fertilizer on the Microbial Community Structure and Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, F.; Udikovic-Kolic, N.; Andrew, S.; Handelsman, J. Diverse antibiotic resistance genes in dairy cow manure. mBio 2014, 5, e01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chai, B. Fate of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Changes in Bacterial Community with Increasing Breeding Scale of Layer Manure. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 857046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esperón, F.; Sacristán, C.; Carballo, M.; de la Torre, A. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Animal Manure, Manure-Amended and Nonanthropogenically Impacted Soils in Spain. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Brassard, P.; Godbout, S.; Létourneau, V.; Turgeon, N.; Rossi, F.; Lachance, É.; Veillette, M.; Gaucher, M.L.; Duchaine, C. Contribution of Manure-Spreading Operations to Bioaerosols and Antibiotic Resistance Genes’ Emission. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Han, W.; Chen, S.; Dong, W.; Qiao, M.; Hu, C.; Liu, B. Fifteen-Year Application of Manure and Chemical Fertilizers Differently Impacts Soil ARGs and Microbial Community Structure. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Xu, W.; Han, Y. ARGs distribution and high-risk ARGs identification based on continuous application of manure in purple soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Yao, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. Potential role of organic matter in the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes in black soils. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 227, 112946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Tang, X.; Liu, C. Bacterial communities regulate temporal variations of the antibiotic resistome in soil following manure amendment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 29241–29252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marutescu, L.; Jaga, M.; Postolache, C.; Barbuceanu, F.; Milita, N.; Romascu, L.M.; Schmitt, H.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; Sefeedpari, P.; Glaeser, S.; et al. Insights into the impact of manure on the environmental antibiotic residues and resistance pool. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 965132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.W.; Han, X.M.; Shi, X.Z.; Wang, J.T.; Han, L.L.; Chen, D.; He, J.Z. Temporal changes of antibiotic-resistance genes and bacterial communities in two contrasting soils treated with cattle manure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiv169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wang, X.; Luo, X.; Lu, F.; Zhao, H. Explore the Contamination of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (ARB) of the Processing Lines at Typical Broiler Slaughterhouse in China. Foods 2025, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, K.; Huang, J.; Topp, E.; Xia, Y. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals the Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance from Manure-Fertilized Soil to Carrot Microbiome. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, R.; Obize, C.; Sibanda, T.; Abia, A.L.K.; Long, H. Evolution and Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance in Given Ecosystems: Possible Strategies for Addressing the Challenge of Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.-J.; Su, J.-Q.; Stedfeld, R. Diversity, abundance, and persistence of antibiotic resistance genes in various types of animal manure following industrial composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Wei, Z.; Banerjee, S.; Friman, V.-P.; Mei, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q. Livestock Manure Type Affects Microbial Community Composition and Assembly During Composting. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 621126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, I.; Naz, B.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Attia, K.; Ayub, N.; Ali, I.; Mohammed, A.A.; Faisal, S.; et al. Interplay among manures, vegetable types, and tetracycline resistance genes in rhizosphere microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1392789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.C.; Breyer, G.M.; Riveros Escalona, M.A.; Mayer, F.Q.; Muterle Varela, A.P.; Ariston de Carvalho Azevedo, V.; Matiuzzi da Costa, M.; Aburjaile, F.F.; Dorn, M.; Brenig, B.; et al. Exploring bacterial diversity and antimicrobial resistance gene on a southern Brazilian swine farm. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 352, 124146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Mathieu, J.; Stadler, L.; Senehi, N.; Sun, R.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Antibiotic resistance genes from livestock waste: Occurrence, dissemination, and treatment. npj Clean. Water 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifedinezi, O.V.; Nnaji, N.D.; Anumudu, C.K.; Ekwueme, C.T.; Uhegwu, C.C.; Ihenetu, F.C.; Obioha, P.; Simon, B.O.; Ezechukwu, P.S.; Onyeaka, H. Environmental Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Food Safety and Public Health. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, M.; Błażejewska, A.; Czapko, A.; Popowska, M. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Animal Manure—Consequences of Its Application in Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 610656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, R.I.; Koike, S.; Krapac, I.; Chee-Sanford, J.; Maxwell, S.; Aminov, R.I. Tetracycline residues and tetracycline resistance genes in groundwater impacted by swine production facilities. Anim. Biotechnol. 2006, 17, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wojnarowski, K.; Cholewińska, P.; Palić, D. Current Trends in Approaches to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquatic Veterinary Medicine. Pathogens 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittredge, H.; Dougherty, K.; Evans, S. Horizontal gene transfer facilitates the spread of extracellular antibiotic resistance genes in soil. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilaire, S.; Radolinski, J.; Xia, K.; Stewart, R.; Chen, C.; Maguire, R. Subsurface Manure Injection Reduces Surface Transport of Antibiotic Resistance Genes but May Create Antibiotic Resistance Hotspots in Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14972–14981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, C.T.; Heuer, H.; Kaupenjohann, M.; Smalla, K. Piggery manure used for soil fertilization is a reservoir for transferable antibiotic resistance plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Topp, E. Abundance of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bacteriophage following Soil Fertilization with Dairy Manure or Municipal Biosolids, and Evidence for Potential Transduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7905–7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Fang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Du, S. Transmission pathways and intrinsic mechanisms of antibiotic resistance genes in soil-plant systems: A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Kong, L.; Gao, H.; Cheng, X.; Wang, X. A Review of Current Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics in Food Animals. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 822689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, R.; Scott, A.; Tien, Y.C.; Murray, R.; Sabourin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Topp, E. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5701–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Literature Review of Contaminants in Livestock and Poultry Manure and Implications for Water Quality; EPA 820-R-13-002; EPA United States: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Bai, F.; Luo, M.; Tang, J. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus from yak. Food Saf. Health 2023, 1, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.; Williams-Nguyen, J. Human health impacts of antibiotic use in agriculture: A push for improved causal inference. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19C, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/about/index.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Bennani, H.; Mateus, A.; Mays, N.; Eastmure, E.; Stärk, K.D.C.; Häsler, B. Overview of Evidence of Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyi-Loh, C.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.; Okoh, A. Antibiotic Use in Agriculture and Its Consequential Resistance in Environmental Sources: Potential Public Health Implications. Molecules 2018, 23, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, A.N.; Gelfand, I.; Schabenberger, O.; Cai, M.; Ma, X.; Chung, W. Target Tillage to Protect the Soil. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/target_tillage_to_protect_the_soil (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- El Mekkaoui, A.; Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Douaik, A.; El Haddadi, R.; Bouhlal, O.; Elomari, M.; Ganoudi, M.; Zouahri, A.; Chakiri, S. Effects of Tillage Systems on the Physical Properties of Soils in a Semi-Arid Region of Morocco. Agriculture 2023, 13, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abagandura, G.O.; Nasr, G.E.; Moumen, N.M. Influence of Tillage Practices on Soil Physical Properties and Growth and Yield of Maize in Jabal al Akhdar, Libya. Open J. Soil Sci. 2017, 7, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbulakshmi, S.; Saravanan, N.; Subbian, P. Conventional Tillage vs Conservation Tillage—A Review. Agric. Rev. 2009, 30, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, L.R.; Thompson, A.M.; Arriaga, F.J.; Koropeckyj-Cox, L.; Yuan, Y. Effectiveness of Residue and Tillage Management on Runoff Pollutant Reduction from Agricultural Areas. J. Asabe 2023, 66, 1341–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerton, L.; Greener, M.; Patterson, D.; Brown, C.D. Effects of soil redistribution by tillage on subsequent transport of pesticide to subsurface drains. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadermeier, F.; Berner, A.; Fliessbach, A.; Friedel, J.; Mäder, P. Impact of reduced tillage on soil organic carbon and nutrient budgets under organic farming. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012, 27, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabayi, A.; Girei, A.; Tijjani Mahmud, A.; Onokebhagbe, V.; Santuraki, H.A.; Nzamouhe, M.; Yusif, S.A. Review of various studies of tillage practices on some soil physical and biological properties. Soil Sci. 2021, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Xue, J.-F.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Kong, F.-L.; Chen, F.; Lal, R.; Zhang, H.-L. Stratification and Storage of Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen as Affected by Tillage Practices in the North China Plain. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alletto, L.; Coquet, Y.; Benoit, P.; Heddadj, D.; Barriuso, E. Tillage management effects on pesticide fate in soils. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 367–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembaid, I.; Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Douaik, A.; Bouhaouss, A. Modeling the effects of farming management practices on soil organic carbon stock under two tillage practices in a semi-arid region, Morocco. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calistru, A.E.; Filipov, F.; Cara, I.G.; Cioboată, M.; Țopa, D.; Jităreanu, G. Tillage and Straw Management Practices Influences Soil Nutrient Distribution: A Case Study from North-Eastern Romania. Land 2024, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.W.; Dungan, R.S.; Moore, A.; Leytem, A.B. Occurrence and abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soil receiving dairy manure. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, M.M.; Ashworth, A.J.; Feye, K.M.; Ricke, S.C.; Owens, P.R.; Moore, P.A.; Savin, M. Long-term impacts of conservation pasture management in manuresheds on system-level microbiome and antibiotic resistance genes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1227006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.A.; Durso, L.M.; Gilley, J.E.; Waldrip, H.M.; Castleberry, L.; Millmier-Schmidt, A. Antibiotic resistance gene profile changes in cropland soil after manure application and rainfall. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, S.I.; Armatoli, P.; Ceccherini, M.T.; Ascher-Jenull, J.; Nannipieri, P.; Pietramellara, G.; D’Acqui, L.P. Physical protection of extracellular and intracellular DNA in soil aggregates against simulated natural oxidative processes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 165, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Feng, R.; Huang, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, F. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Agricultural Soils: A Comprehensive Review of the Hidden Crisis and Exploring Control Strategies. Toxics 2025, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commelin, M.C.; Baartman, J.E.M.; Zomer, P.; Riksen, M.; Geissen, V. Pesticides are Substantially Transported in Particulate Phase, Driven by Land use, Rainfall Event and Pesticide Characteristics—A Runoff and Erosion Study in a Small Agricultural Catchment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 830589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, F.; Nybroe, O.; Zheng, B.; Badawi, N.; Hao, X.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Aamand, J. Preferential flow paths shape the structure of bacterial communities in a clayey till depth profile. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhuang, J. The Effect of Manure Application Rates on the Vertical Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Farmland Soil. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhum, K.V.; Vargas, R.C.; Boolchandani, M.; D’Souza, A.W.; Patel, S.; Kesaraju, A.; Walljasper, G.; Hegde, H.; Ye, Z.; Valenzuela, R.K.; et al. Manure Microbial Communities and Resistance Profiles Reconfigure after Transition to Manure Pits and Differ from Those in Fertilized Field Soil. mBio 2021, 12, e00798-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Motta, A.C.; Burmester, C.H.; Reeves, D.W.; van Santen, E.; Osborne, J.A. Effects of Tillage Systems on Soil Microbial Community Structure Under a Continuous Cotton Cropping System. In Making Conservation Tillage Conventional: Building a Future on 25 Years of Research, Proceedings of the 25th Annual Southern Conservation Tillage Conference for Sustainable Agriculture, Auburn, AL, USA, 24–26 June 2002; Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station: Auburn, AL, USA, 2002; pp. 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, R.P.; Feng, Y.; Githinji, L.; Ankumah, R.; Balkcom, K. Impact of No-Tillage and Conventional Tillage Systems on Soil Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2012, 2012, 548620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgason, B.; Walley, F.; Germida, J. Fungal and Bacterial Abundance in Long-Term No-Till and Intensive-Till Soils of the Northern Great Plains. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Motta, A.C.; Reeves, D.W.; Burmester, C.H.; van Santen, E.; Osborne, J.A. Soil microbial communities under conventional-till and no-till continuous cotton systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dai, Z.; Veach, A.M.; Zheng, J.; Xu, J.; Schadt, C.W. Global meta-analyses show that conservation tillage practices promote soil fungal and bacterial biomass. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 293, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeleder, R.D.; Miller, J.J.; Ball Coelho, B.R.; Roy, R.C. Impacts of tillage, cover crop, and nitrogen on populations of earthworms, microarthropods, and soil fungi in a cultivated fragile soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2006, 33, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Al-Mutairi, K.A. Earthworms Effect on Microbial Population and Soil Fertility as Well as Their Interaction with Agriculture Practices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Li, L.; Liang, X.; Fine, A.; Zhuang, J.; Radosevich, M.; Schaeffer, S.M. Variation in Bacterial Community Structure Under Long-Term Fertilization, Tillage, and Cover Cropping in Continuous Cotton Production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 847005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, H.M.; Xu, L.; Gao, C.; Spinner, H.B.; Taylor, J.; Lemaux, P.; Mitchell, J.; Coleman-Derr, D. Agricultural Soil Management Practices Differentially Shape the Bacterial and Fungal Microbiome of Sorghum bicolor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02345-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, L.; Xie, J.; Coulter, J.A.; Zhang, R.; Luo, Z.; Cai, L.; Wang, L.; Gopalakrishnan, S. Soil Bacterial Diversity and Potential Functions Are Regulated by Long-Term Conservation Tillage and Straw Mulching. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chang, S.X. Minimum tillage and residue retention increase soil microbial population size and diversity: Implications for conservation tillage. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W. Tillage Practices and Residue Management Manipulate Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities and Networks in Maize Agroecosystems. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, S.G.; Buehring, N.W.; Prevost, J.D.; Kingery, W.L. Soil Bacterial Community Diversity and Composition as Affected by Tillage Intensity Treatments in Corn-Soybean Production Systems. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 12, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, A.G.; Brooks, J.P.; Locke, M.A.; Morin, D.J.; Brown, A.; Baker, B.H. Soil bacterial community dynamics in plots managed with cover crops and no-till farming in the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, USA. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, A.Y.; Ammar, H.A.; Subedi, A.; Pimentel, M.; Cook, R.L.; Bond, J.; Fakhoury, A.M. Microbial Communities Associated With Long-Term Tillage and Fertility Treatments in a Corn-Soybean Cropping System. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degrune, F.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Colinet, G.; Hiel, M.-P.; Bodson, B.; Taminiau, B.; Daube, G.; Vandenbol, M.; Hartmann, M. Temporal Dynamics of Soil Microbial Communities below the Seedbed under Two Contrasting Tillage Regimes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Li, W.; Dong, W.; Tian, Y.; Hu, C.; Liu, B. Tillage Changes Vertical Distribution of Soil Bacterial and Fungal Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, B.; Hu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, X.; Liu, K.; Li, C. Effects of deep tillage and straw returning on soil microorganism and enzyme activities. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 451493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gahagan, A.C.; Morrison, M.J.; Gregorich, E.; Lapen, D.R.; Chen, W. Stratified Effects of Tillage and Crop Rotations on Soil Microbes in Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles at Different Soil Depths in Long-Term Corn, Soybean, and Wheat Cultivation. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.S.; Philippot, L. Insights into the resistance and resilience of the soil microbial community. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, U.B.; Sahu, P.K.; Paul, S.; Kumar, A.; Malviya, D.; Singh, S.; Kuppusamy, P.; Singh, P.; Paul, D.; et al. Linking Soil Microbial Diversity to Modern Agriculture Practices: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, D.C.; Gamble, J.D.; Castle, S.; Rogers, J.; Wilson, M. Abiotic and biotic filters determine the response of soil bacterial communities to manure amendment. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 180, 104618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngquist, C.P.; Mitchell, S.M.; Cogger, C.G. Fate of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance during Digestion and Composting: A Review. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendooven, L.; Pérez-Hernández, V.; Gómez-Acata, S.; Verhulst, N.; Govaerts, B.; Luna-Guido, M.L.; Navarro-Noya, Y.E. The Fungal and Protist Community as Affected by Tillage, Crop Residue Burning and N Fertilizer Application. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Sun, Y.; Qin, Q.; Sun, L.; Zheng, X.; Terzaghi, W.; Lv, W.; Xue, Y. The Effects of Earthworms on Fungal Diversity and Community Structure in Farmland Soil with Returned Straw. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 594265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosberg, A.K.; Silva, M.J.; Skøtt Feidenhans’l, C.; Cytryn, E.; Jurkevitch, E.; Lood, R. Regulation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes on Agricultural Land Is Dependent on Both Choice of Organic Amendment and Prevalence of Predatory Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Lu, Y.-S.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Peng, H.-L.; Shi, C.-H.; Xie, K.-Z.; Zhang, K.; Sun, L.-L.; et al. Impact of different continuous fertilizations on the antibiotic resistome associated with a subtropical triple-cropping system over one decade. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Shi, J.; Jia, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z. Correlation between Exogenous Compounds and the Horizontal Transfer of Plasmid-Borne Antibiotic Resistance Genes. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Han, S.; Li, X. Regulatory strategies for inhibiting horizontal gene transfer of ARGs in paddy and dryland soil through computer-based methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, C.; Cui, P.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Yang, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhou, S.; Liao, H.; et al. Viral and thermal lysis facilitates transmission of antibiotic resistance genes during composting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0069524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, J.P.; Zhang, L.; Parrott, B.B.; Seaman, J.C. Plasmid size determines adsorption to clay and breakthrough in a saturated sand column. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guron, G.K.P.; Arango-Argoty, G.; Zhang, L.; Pruden, A.; Ponder, M.A. Effects of Dairy Manure-Based Amendments and Soil Texture on Lettuce- and Radish-Associated Microbiota and Resistomes. mSphere 2019, 4, e00239-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, T.; Fernandez, E.; Laëtitia, F.; Destandau, E.; Boussafir, M.; Sohmiya, M.; Sugahara, Y.; Guegan, R. Competitive Association of Antibiotics with a Clay Mineral and Organoclay Derivatives as a Control of Their Lifetimes in the Environment. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 15332–15342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, C.; Penton, C.R.; Liu, C.; Tao, C.; Deng, X.; Ou, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, R. Patterns of fungal community succession triggered by C/N ratios during composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietra, R.; Berendsen, B.J.A.; Mi-Gegotek, Y.; Römkens, P.; Pustjens, A.M. Prediction of the mobility and persistence of eight antibiotics based on soil characteristics. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guron, G.K.P.; Chen, C.; Du, P.; Pruden, A.; Ponder, M.A. Manure-Based Amendments Influence Surface-Associated Bacteria and Markers of Antibiotic Resistance on Radishes Grown in Soils with Different Textures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02753-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, D.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.A. A meta-analysis of pesticide loss in runoff under conventional tillage and no-till management. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ou, Y.; Ling, S.; Gao, M.; Deng, X.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Z.; Shen, Q. Suppressing Ralstonia solanacearum and Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Tomato Rhizosphere Soil through Companion Planting with Basil or Cilantro. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, E.; Szlatenyi, D.; Csenki, S.; Alrwashdeh, J.; Czako, I.; Láng, V. Farming Practice Variability and Its Implications for Soil Health in Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Wen, M.; Zhou, N.; Wang, J. Crop rotation complexity affects soil properties shaping antibiotic resistance gene types and resistance mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1603518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chen, P.; Du, Q.; Yang, H.; Luo, K.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Yong, T.; Yang, W. Soil Organic Matter, Aggregates, and Microbial Characteristics of Intercropping Soybean under Straw Incorporation and N Input. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yao, X.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, C.; Sun, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, D.; et al. Growth of microbes in competitive lifestyles promotes increased ARGs in soil microbiota: Insights based on genetic traits. Microbiome 2025, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalucco, L. Soil Quality as Affected by Intensive Versus Conservative Agricultural Managements. 2017. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/environmentalscience/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389414-e-282 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Sairam, M.; Maitra, S.; Sahoo, U.; Raghava, C.V.; Santosh, D.T.; Bhattacharya, U. Impact of Conservation Tillage on Soil Properties for Agricultural Sustainability: A Review. Int. J. Bioresour. Sci. 2024, 10, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, M.A.; Al-Kaisi, M. Strip-tillage effect on seedbed soil temperature and other soil physical properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 80, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zang, H.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, Y. Manure input propagated antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors in soils by regulating microbial carbon metabolism. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, X.; Guan, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, F.; Song, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, B.; et al. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from soil to wheat: Role of host bacteria, impact on seed-derived bacteria, and affecting factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jin, Q.; Zhu, N.; Hu, B.; Gao, Y. Fallow practice mitigates antibiotic resistance genes in soil by shifting host bacterial survival strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelevtsova, L.; Azhogina, T.; Karchava, S.; Klimova, M.; Polienko, E.; Litsevich, A.; Chernyshenko, E.; Khammami, M.; Sazykin, I.; Sazykina, M. Effect of Mineral Fertilizers and Pesticides Application on Bacterial Community and Antibiotic-Resistance Genes Distribution in Agricultural Soils. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Chu, H.; Lin, X. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in soils after continually applied with different manure for 30 years. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 340, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Peng, A.; Gu, C.; Boyd, S.A.; Li, H. Antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial communities in cornfield and pasture soils receiving swine and dairy manures. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Wang, F.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Sheng, H.; Li, Z.; Hashsham, S.A.; Jiang, X.; Tiedje, J.M. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from soil to rice in paddy field. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Han, Z.; Zhu, D.; Luan, X.; Deng, L.; Dong, L.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y. Field-based evidence for the enrichment of intrinsic antibiotic resistome stimulated by plant-derived fertilizer in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 135, 728–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, H.; Schmitt, H.; Smalla, K. Antibiotic resistance gene spread due to manure application on agricultural fields. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Johnson, T.A.; Su, J.Q.; Qiao, M.; Guo, G.X.; Stedtfeld, R.D.; Hashsham, S.A.; Tiedje, J.M. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3435–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, D.; Clarke, J.L.; van Eerde, A. Pollution by Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in LiveStock and Poultry Manure in China, and Countermeasures. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udikovic-Kolic, N.; Wichmann, F.; Broderick, N.A.; Handelsman, J. Bloom of resident antibiotic-resistant bacteria in soil following manure fertilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15202–15207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, R.; Lv, J.; Li, B.; Yang, F.; Zheng, X.; Xu, J. Antibiotic resistance genes in different animal manures and their derived organic fertilizer. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Hu, H.-W.; Gou, M.; Wang, J.-T.; Chen, D.; He, J.-Z. Temporal succession of soil antibiotic resistance genes following application of swine, cattle and poultry manures spiked with or without antibiotics. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1621–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.; Ward, M.; van Bunnik, B.; Farrar, J. Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Shen, Q.; Liu, F.; Ma, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M. Antibiotic resistance gene abundances associated with antibiotics and heavy metals in animal manures and agricultural soils adjacent to feedlots in Shanghai; China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 235–236, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Cao, R.; Mo, S.; Yao, R.; Ren, Z.; Wu, J. Swine Manure Composting with Compound Microbial Inoculants: Removal of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Associations with Microbial Community. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 592592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne-Bailey, K.G.; Gaze, W.H.; Zhang, L.; Kay, P.; Boxall, A.; Hawkey, P.M.; Wellington, E.M. Integron prevalence and diversity in manured soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J. Field-based evidence for enrichment of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in manure-amended vegetable soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.T.; Ma, R.A.; Zhu, D.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Zhu, Y.G.; Zhang, S.Y. Organic fertilization co-selects genetically linked antibiotic and metal(loid) resistance genes in global soil microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, R.; Tien, Y.C.; Murray, R.; Scott, A.; Sabourin, L.; Topp, E. Safely coupling livestock and crop production systems: How rapidly do antibiotic resistance genes dissipate in soil following a commercial application of swine or dairy manure? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3258–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, X.; Thomas, B.W.; McAllister, T.A.; Workentine, M.; Jin, L.; Shi, X.; Alexander, T.W. Soil antibiotic resistance genes accumulate at different rates over four decades of manure application. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygens, J.; Rasschaert, G.; Heyndrickx, M.; Dewulf, J.; Van Coillie, E.; Quataert, P.; Daeseleire, E.; Becue, I. Impact of fertilization with pig or calf slurry on antibiotic residues and resistance genes in the soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, N. Veterinary antibiotics in the aquatic and terrestrial environment. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.-C.; Wu, R.-T.; Chen, Y.-X.; Cheng, Z.-W.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.-W.; Liao, X.-D. Elimination and analysis of mcr-1 and blaNDM-1 in different composting pile layers under semipermeable membrane composting with copper-contaminated poultry manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 332, 125076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Shen, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, K. Exploring antibiotic resistance load in paddy-upland rotation fields amended with commercial organic and chemical/slow release fertilizer. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1184238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Datta, R.; Lal, R.; Vijayakumar, V.; Brtnicky, M.; Sharma, M.P.; Yadav, G.S.; Jhariya, M.K.; Jangir, C.K.; et al. Impact of Agrochemicals on Soil Microbiota and Management: A Review. Land 2020, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rajhi, A.M.H.; Saddiq, A.A.; Ismail, K.S.; Abdelghany, T.M.; Mohammad, A.M.; Selim, S. White Rot Fungi to Decompose Organophosphorus Insecticides and their Relation to Soil Microbial Load and Ligninolytic Enzymes. BioResources 2024, 19, 9468–9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C: Environmental Carcinogenesis and Ecotoxicology Reviews. Food Chem. 1984, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Xiao, L.; Lin, D.; Zhang, T.L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, D.; Qian, H.; Rillig, M.C.; et al. Increasing pesticide diversity impairs soil microbial functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2419917122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelbrick, M.; Hesse, E.; Brien, S.O. Cultivating antimicrobial resistance: How intensive agriculture ploughs the way for antibiotic resistance. Microbiology 2023, 169, 001384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebMandal, M.; Mandal, S.; Pal, N.K. Antibiotic resistance prevalence and pattern in environmental bacterial isolates. Open Antimicrob. Agents J. 2011, 3, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, M. Chlorpyrifos and Chlorpyrifos-methyl Can Promote Conjugative Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance Genes. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 59, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.L.; Chen, Q.L.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, Y.G.; Gillings, M.R.; Su, J.Q. Impact of Wastewater Treatment on the Prevalence of Integrons and the Genetic Diversity of Integron Gene Cassettes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02766-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawole, O.; Aluko, M.; Olowonihi, T. Effects of a Carbendazim-Mancozeb fungicidal mixture on soil microbial populations and some enzyme activities in soil. Agrosearch 2010, 10, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhu, D.; Quintela-baluja, M.; Graham, D.W.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Qiao, M. Increased Transmission of Antibiotic Resistance Occurs in a Soil Food Chain under Pesticide Stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21989–22001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Qiu, M.; Zhan, X.; Zheng, C.; Shi, N.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; et al. A novel bidirectional regulation mechanism of mancozeb on the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, R.L.; Senseman, S.A.; Hons, F.M.; Zuberer, D.A. Effect of glyphosate on soil microbial activity and biomass. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Cui, P.; Wen, C.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Che, J.; et al. Herbicide Selection Promotes Antibiotic Resistance in Soil Microbiomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2337–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Wu, S.; Men, Y. Exposure to Environmental Levels of Pesticides Stimulates and Diversifies Evolution in Escherichia coli toward Higher Antibiotic Resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8770–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregi, L.; Epelde, L.; Alkorta, I.; Garbisu, C. Antibiotic Resistance in Agricultural Soil and Crops Associated to the Application of Cow Manure-Derived Amendments from Conventional and Organic Livestock Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 633858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanissery, R.; Gairhe, B.; Kadyampakeni, D.; Batuman, O.; Alferez, F. Glyphosate: Its Environmental Persistence and Impact on Crop Health and Nutrition. Plants 2019, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Chen, L.; Deng, X.W.; Tang, X. Development of herbicide resistance genes and their application in rice. Crop J. 2022, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Zeyaullah, M.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Muzammil, K.; Saati, A.A.; Wahab, S.; Elbendary, E.Y.; Kambal, N.; et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragićević, M.; Platiša, J.; Nikolić, R.; Todorović, S.; Bogdanović, M.; Mitić, N.; Simonović, A. Herbicide phosphinothricin causes direct stimulation hormesis. Dose Response 2012, 11, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.N.; Singh, V.K.; Mathur, M.; Srivastava, R.C. Studies with phorate, an organophosphate insecticide, on some enzymes of nitrogen metabolism in Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper. Biol. Plant. 1989, 31, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, S.; Ghosh, P.; Mandal, S.; Sasmal, D.; Kundu, S.; Sengupta, S.; Kanthal, S.; Sarkar, T. Organophosphate Pesticide: Environmental impact and toxicity to organisms. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2024, 7, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omar, M.S.; Naz, M.; Mohammed, S.A.A.; Mansha, M.; Ansari, M.N.; Rehman, N.U.; Kamal, M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Yusuf, M.; Hamad, A.M.; et al. Pyrethroid-Induced Organ Toxicity and Anti-Oxidant-Supplemented Amelioration of Toxicity and Organ Damage: The Protective Roles of Ascorbic Acid and α-Tocopherol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamad, A.; Kumar, J. Pyrethroid pesticides: An overview on classification, toxicological assessment and monitoring. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 10, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Filip, M.; Ostafe, V.; Isvoran, A. Effects of Triazole Fungicides on Soil Microbiota and on the Activities of Enzymes Found in Soil: A Review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, D.L.; Voiculescu, D.I.; Ostafe, V.; Ciorsac, A.; Isvoran, A. A review of the toxicity of triazole fungicides approved to be used in European Union to the soil and aqueous environment. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Chem. 2022, 33, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ma, L.; Yu, Q.; Yang, J.; Su, W.; Hilal, M.G.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, H. The source, fate and prospect of antibiotic resistance genes in soil: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 976657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Scoy, A.; Pennell, A.; Zhang, X. Environmental Fate and Toxicology of Dimethoate. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 237, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, A.R.; Kroer, N. Effects of stress and other environmental factors on horizontal plasmid transfer assessed by direct quantification of discrete transfer events. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 59, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isha, S.T.; Rajesh, L. Effect of pesticides on crop, soil microbial flora and determination of pesticide residue in agricultural produce: A review. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, I.; Mohammed, D.; Nassreddine, M.; Kenza Ait El, K. Assessing the Impact of Precision Farming Technologies: A Literature Review. World J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2024, 2, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katada, S.; Fukuda, A.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Azuma, T.; Takei, A.; Takada, H.; Okamoto, E.; Kato, T.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Aerobic Composting and Anaerobic Digestion Decrease the Copy Numbers of Antibiotic-Resistant Genes and the Levels of Lactose-Degrading Enterobacteriaceae in Dairy Farms in Hokkaido, Japan. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 737420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Brightwell, G. Genetic determinants of thermal resistance in foodborne bacterial pathogens. Food Saf. Health 2024, 2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; Nemecek, T.; Liang, C.; Zhao, C.; Yu, A.; Coulter, J.A.; Wang, Y.; Hu, F.; Wang, L.; Siddique, K.H.M.; et al. Integrated farming with intercropping increases food production while reducing environmental footprint. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2106382118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R.; Zi, Z.; Wang, P.; Noor, H.; Ren, A.; Ren, Y.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effects of Five Consecutive Years of Fallow Tillage on Soil Microbial Community Structure and Winter Wheat Yield. Agronomy 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Fiaz, S. Effects of Fallow Management Practices on Soil Water, Crop Yield and Water Use Efficiency in Winter Wheat Monoculture System: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 825309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.H.; Hubbard, N.; Loudjani, P.; Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission; Monitoring Agriculture ResourceS (MARS) Unit H04. Precision Agriculture: An Opportunity for EU Farmers—Potential Support with the CAP 2014–2020; PE 529.049; European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Basil, S.; Zhu, C.; Huo, Z.; Xu, S. Current Progress on Antibiotic Resistance Genes Removal by Composting in Sewage Sludge: Influencing Factors and Possible Mechanisms. Water 2024, 16, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congilosi, J.L.; Aga, D.S. Review on the fate of antimicrobials, antimicrobial resistance genes, and other micropollutants in manure during enhanced anaerobic digestion and composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 123634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.Y.; Chow, Y.-L. Exploring the potential of spice-derived phytochemicals as alternative antimicrobial agents. eFood 2024, 5, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Man, S.; Ye, S.; Chen, K.; Ma, L. A CRISPR/dCas9-enabled, on-site, visual, and bimodal biosensing strategy for ultrasensitive and self-validating detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Food Front. 2023, 4, 2070–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, A.; Szólik, E.; Desalegn, G.; Tőzsér, D. A Systematic Review of Opportunities and Limitations of Innovative Practices in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padiyara, P.; Inoue, H.; Sprenger, M. Global Governance Mechanisms to Address Antimicrobial Resistance. Infect Dis. 2018, 11, 1178633718767887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pesticide Type | Representative Compound | Mode of Action | Effect on Crops | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbicide | Glyphosate | Inhibits EPSP synthase, blocks aromatic amino acid synthesis | Suppresses plant growth; inhibits root development; affects rhizosphere microbes | [161,162] |

| Herbicide | Phosphinic acid | Inhibits glutamine synthetase | Disrupts nitrogen metabolism, affects plant growth | [163,164] |

| Insecticide | Organophosphates | Inhibits acetylcholinesterase, interferes with neural transmission | May affect crop physiological functions | [165,166] |

| Insecticide | Pyrethroids | Disrupts sodium channels, affects nervous system | May have toxic effects on crops | [167,168] |

| Fungicide | Benzimidazoles | Inhibits microtubule formation, disrupts cell division | Suppresses fungal growth, protects crops | [163] |

| Fungicide | Triazoles | Inhibits ergosterol synthesis, disrupts cell membranes | Suppresses fungal growth, protects crops | [169,170] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, F.; Wu, Q.; Ding, Y. Exploring the Relationship Between Farmland Management and Manure-Derived Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Prevention and Control Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111117

Huang C, Zeng Y, Yang F, Wu Q, Ding Y. Exploring the Relationship Between Farmland Management and Manure-Derived Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Prevention and Control Strategies. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(11):1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111117

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Chengcheng, Yuanye Zeng, Fengxia Yang, Qixin Wu, and Yongzhen Ding. 2025. "Exploring the Relationship Between Farmland Management and Manure-Derived Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Prevention and Control Strategies" Antibiotics 14, no. 11: 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111117

APA StyleHuang, C., Zeng, Y., Yang, F., Wu, Q., & Ding, Y. (2025). Exploring the Relationship Between Farmland Management and Manure-Derived Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Prevention and Control Strategies. Antibiotics, 14(11), 1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111117