Abstract

Background/Objectives: This study characterized the phenotypic and genotypic profiles of antimicrobial resistance in 104 Escherichia coli isolates obtained from 22 samples of artisanal Minas Frescal cheese from the Federal District, Brazil. Methods: The antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli isolates was assessed using the disk diffusion method and antimicrobial resistance genes were detected using polymerase chain reaction methods with specific primers. Results: The highest rates of phenotypic antimicrobial resistance were observed for sulfonamides (85.58%, 89/104) and tetracyclines (38.46%, 40/104). In the genotypic profiles, most E. coli isolates carried the sulfonamide resistance genes sul1/sul2 (62.50%, 65/104), tetracycline resistance genes tetA/tetB (65.38%, 68/104), and β-lactam resistance genes blaCTX-M/blaTEM/blaSHV (55.77%, 58/104). Most E. coli strains that presented sulfonamide resistance genes carried the sul1 gene (49.04%, 51/104) and were phenotypically sulfonamide-resistant strains (59.61%, 62/104). Regarding the E. coli strains that carried tetracycline resistance genes, the majority harbored both tetA and tetB genes (34.61%, 36/104), with 35.56% (37/104) being phenotypically resistant and 29.80% (31/104) being phenotypically susceptible. For E. coli strains that presented β-lactam resistance genes, the most frequently detected gene was blaCTX-M (21.15%, 22/104) and, notably, most E. coli strains (43.26%, 45/104) were phenotypically susceptible. The cat1 and clmA genes (associated with phenicol resistance) were detected in 22.12% of the E. coli isolates (23/104), with only two strains (1.92%) being phenotypically resistant to chloramphenicol. Conclusion: The high prevalence of E. coli carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in artisanal cheese raises public health concerns regarding the dissemination of potentially pathogenic antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms through the food chain.

1. Introduction

Brazil is the largest milk producer in South America, the fourth largest in the world, and one of the top five globally, with an annual production exceeding 34 billion liters [1,2]. Minas Frescal cheese is a typical Brazilian product and ranks third in national cheese consumption, with high availability and low cost in the domestic market [3].

Minas Frescal cheese is characterized by a raw mass with a soft texture, white appearance, and a slightly acidic and salty flavor [4]. It is a fresh cheese, meaning it is not aged, with a high moisture content, medium fat content, and a pH close to neutrality. It is produced through enzymatic coagulation of cow’s milk using rennet and/or other appropriate coagulating enzymes [5,6].

According to Brazilian regulations, the production of Minas Frescal cheese must use milk subjected to pasteurization or an equivalent thermal treatment to ensure the safety of the product. The commercialization of Minas Frescal cheese made with raw milk is not permitted, as the cheese does not undergo a maturation process. Due to its lack of maturation and high moisture content (above 55%), the cheese must be stored at the correct refrigeration temperature (not exceeding 8 °C) and has a short shelf life (approximately 15 days) [5].

In Brazil, Minas Frescal cheese is industrially produced in dairy factories using pasteurized milk and is sold in supermarkets in refrigerated shelves and in packaging containing the seal of the sanitary inspection service. However, the Brazilian market also includes artisanal Minas Frescal cheeses, which are typically produced on small rural properties and commonly sold at open-air markets and farmers’ markets. These cheeses are often sold without branding on the packaging, without refrigeration, and are frequently made from raw milk and handled under inadequate hygienic conditions, making them susceptible to a high presence of pathogenic microorganisms, which compromises their quality and poses a food safety risk to consumers. The main pathogens isolated from these cheeses are Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes, which frequently cause outbreaks of foodborne diseases worldwide [7,8,9,10,11].

Some studies have shown that artisanal cheeses produced in different regions of Brazil do not meet the microbiological criteria established by national laws, mainly due to high levels of S. aureus and E. coli [8,11,12]. Escherichia coli predominantly lives as a commensal bacterium in the intestinal microbiota of humans and homeothermic animals. However, pathogenic strains of E. coli can cause various diseases, with these bacteria being one of the main causes of gastrointestinal infections in humans, primarily transmitted through contaminated water and food. Consequently, these bacteria are abundant in feces and are regularly used as microbial indicators of the presence of enteropathogenic bacteria in water and food [7,10,13].

E. coli exhibits a high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, both in commensal strains and in those that possess virulence factors. Therefore, it is essential to monitor the antimicrobial resistance profile of E. coli due to its widespread presence in the environment and among various hosts, as well as its ability to transfer resistance genes both inter- and intra-specifically. Consequently, E. coli is commonly used as a microorganism to monitor antimicrobial resistance, given its capacity to acquire resistance genes through horizontal transfer [14,15].

Thus, this study aimed to isolate Escherichia coli strains from artisanal Minas Frescal cheese samples collected at farmers’ markets in the Federal District, Brazil. The E. coli strains were genetically confirmed through the detection of the uidA gene. Antimicrobial susceptibility was assessed using the disk diffusion method (Kirby–Bauer). Recent studies have emphasized the importance of determining the genotypic profiles of antimicrobial resistance in both phenotypically resistant and susceptible bacteria, as many carry silent genes that are not expressed in the phenotypic profile but can be spread through horizontal gene transfer to other bacteria and become active in the new host [16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, while many studies only determine the genotypic profile for E. coli strains that are phenotypically resistant to antimicrobials isolated from milk and cheeses [21,22,23], the present study investigated the presence of resistance genes in all E. coli strains (phenotypically resistant or susceptible to antimicrobials), including sul1 and sul2 (resistance to sulfonamides); tetA and tetB (resistance to tetracyclines); blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV (resistance to β-lactams); and cat1 and clmA (resistance to phenicols).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation of E. coli from Cheese Samples and Determination of the Phenotypic Profile of Antimicrobial Resistance

The results of this study showed that all samples of artisanal Minas Frescal cheese contained thermotolerant coliforms and E. coli, and 31.8% of artisanal cheeses (7/22) exceeded the limit imposed by Brazilian legislation of 3.0 log MPN/g for thermotolerant coliforms [24]. Thermotolerant coliforms are a subgroup of total coliforms that ferment lactose at temperatures between 44.5 and 45.5 °C, with the main representative being the E. coli species, which is exclusively of fecal origin [8]. Food contaminated with E. coli is not strictly associated with foodborne diseases, as this bacterium can commensally inhabit the intestines of humans and various other animals. However, the presence of pathogenic E. coli serotypes in food can cause gastrointestinal illnesses in consumers [13,25].

A total of 104 E. coli strains were isolated from the 22 samples of artisanal Minas Frescal cheese, with genetic confirmation of the uidA and lacZB genes. The uidA gene is used for E. coli confirmation, as it is present in more than 95% of the strains of this bacterium but absent in other Enterobacteriaceae species, making it a specific gene for the detection of E. coli [26,27].

Ahmady et al. [28] isolated 76 suspected E. coli strains from raw cow milk and unpasteurized butter samples collected from dairy stores in Ahvaz, southwest Iran, detecting the uidA gene in 65.9% (50/76) of the strains, which were confirmed to be E. coli. Similarly, Alsanjary et al. [29] analyzed 400 bacteria collected from various dairy herds in Nineveh, Iraq, and observed that 35.0% (140/400) of the strains tested positive for E. coli through the identification of the uidA gene.

Table 1 presents the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the 104 E. coli strains isolated from artisanal Minas Frescal cheese. The highest antimicrobial resistance rates were observed for sulfonamide (85.58%, 89/104) and tetracycline (38.46%, 40/104).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Escherichia coli isolates.

In the literature, several studies have reported high antimicrobial resistance rates to sulfonamides and tetracyclines in E. coli isolated from raw milk and cheeses. Ribeiro et al. [30] reported that 93.0% of potentially pathogenic E. coli strains isolated from raw milk samples in a small Brazilian farm producing fresh raw milk cheese were resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. Messele et al. [31] analyzed 224 raw milk samples collected from cows with mastitis at dairy farms in central Ethiopia and found an E. coli prevalence rate of 7.1% (16), with a phenotypic resistance rate of 50% to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. Shoaib et al. [22] analyzed 209 samples collected from a large dairy farm in Xinjiang province, China, and found that most of the 338 E. coli strains were resistant to sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (62.43%, 211/338) and exhibited a tetracycline resistance rate of 28.99% (98/338). Hassanien and Shaker [32] found E. coli O157:H7 strains in 11.3% of dairy product samples, such as cheeses and yogurts, sold in Egypt, and these strains exhibited high resistance to tetracycline (81.8%). Joubrane et al. [33] analyzed 195 raw milk samples collected in Lebanon; among the 100 isolated E. coli strains, 41.0% showed resistance to tetracycline. De Campos et al. [7] reported that, out of a total of 147 samples of Minas Frescal cheese made from unpasteurized cow’s milk in Brazil, 39 E. coli strains were isolated, with the highest antimicrobial resistance rate found for tetracycline (25.6%).

Antimicrobials such as tetracyclines and sulfonamides are widely used in the treatment of animal diseases. According to the USA’s Food and Drug Administration, in 2021, the estimated proportion of antimicrobial drugs sold for use in food-producing animals, based on therapeutic class, was 67% for tetracyclines, representing the highest sales volume in the domestic market, with approximately 3916 kg of drugs sold. This was followed by penicillins at 10% (619 kg), macrolides at 9% (524 kg), and sulfonamides at 5% (302 kg) [34].

It was observed that among the 104 E. coli strains, only 13 (12.5%) were sensitive to all tested antimicrobials, while 91 (87.5%) exhibited resistance to at least one of the tested antimicrobials. A total of 33 E. coli strains (31.8%) were identified as resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials and were therefore classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. A total of 31 antimicrobial resistance profiles were identified (Table 2), with resistance to SUL being the most frequent, being observed in 32.7% of E. coli strains (34/104), followed by resistance to SUL-TET in 7.7% (8/104) and SUL-TET-CIP in 5.8% (6/104).

Table 2.

Phenotypic antimicrobial resistance patterns of Escherichia coli isolates.

Several studies from different regions have reported a considerable prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli in dairy products. In Egypt, Kasem et al. [35] observed that 82.4% of 17 E. coli isolates from commonly consumed cheese varieties were MDR. In Lebanon, Hussein et al. [36] found that 75.0% (89/118) of E. coli strains from 50 white soft cheese (Akkawi) samples collected from 16 major retail stores in Beirut exhibited multidrug resistance, particularly in unbranded products lacking proper pasteurization. In Ethiopia, Messele et al. [31] reported MDR in 68.7% of E. coli isolates obtained from raw milk sampled at central-region dairy farms, while Adzitey et al. [37] identified MDR in 40.5% (42/250) of E. coli strains recovered from raw cow milk and related products collected from different locations in the Saboba district of Ghana.

Multidrug-resistant E. coli has become a significant concern in human and veterinary medicine. Dairy cattle may serve as reservoirs for zoonotic and antibiotic-resistant strains, facilitating their spread through contaminated farm environments, milk, meat, or direct contact with animals [14,22].

2.2. Determination of the Genotypic Profile of Antimicrobial Resistance of E. coli Isolates

In the present study, 65 E. coli strains (62.50%) out of the 104 analyzed carried sulfonamide resistance genes (Table 3). Most of the isolated E. coli strains harbored the sul1 gene (57.69%, 60/104), with a large proportion of them carrying this gene alone (49.04%, 51/104). In total, 14 E. coli strains (13.46%) carried the sul2 gene, of which only 5 E. coli strains (4.81%) carried sul2 alone. Accordingly, nine E. coli strains (8.65%) harbored both sul1 and sul2 genes simultaneously. In the antibiogram analysis, most E. coli strains were resistant to sulfonamide (85.58%, 89/104), and in the genotypic profile, 62 (59.61%) of these phenotypically sulfonamide-resistant E. coli strains carried the sul1 and/or sul2 genes. This result indicates that 69.66% of phenotypically sulfonamide-resistant E. coli strains carried the sul1 and/or sul2 genes. Furthermore, a small proportion of E. coli strains (2.88%, 3/104) were phenotypically susceptible to sulfonamide but still harbored the sul1 and/or sul2 genes.

Table 3.

Percentage occurrence of various antibiotic resistance genes in 104 Escherichia coli isolates.

Sulfonamides exhibit a broad spectrum of activity against most Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, acting through the competitive inhibition of the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), which is essential for folic acid synthesis in bacteria. Folic acid is crucial for the construction of bacterial DNA and RNA; therefore, inhibiting its synthesis prevents bacterial growth and replication. Sulfonamides have been used for decades in animals and humans and sulfonamide resistance mechanisms have been frequently identified in Gram-negative bacteria, mainly due to the acquisition of three resistance genes (sul1, sul2, and sul3), which encode DHPS isoforms with low affinity for sulfonamides. These resistance genes have been identified in both bacterial chromosomes and plasmids, often associated with mobile genetic elements such as transposons and integrons. This genetic mobility facilitates the transfer of sul genes, contributing to the spread of resistance among different bacterial populations [38,39,40].

The sul1 and sul2 genes are frequently detected in E. coli, while the sul3 gene is much less common. The sul1 gene is highly prevalent due to its location within the 3-conserved segment of class 1 integrons. Consequently, it is frequently co-located with other antimicrobial resistance genes carried on gene cassettes in the variable region of these integrons. Class 1 integrons containing sul1 have been detected in E. coli from both healthy and diseased food-producing animals worldwide. The sul2 gene is also widely distributed among E. coli isolates from different animal species across various regions of the world [38,39].

Ombarak et al. [21] evaluated 25 E. coli isolates phenotypically resistant to sulfonamides from samples of raw milk and the two most popular cheeses in Egypt and found that 25 strains (100%) carried the sul2 gene, 7 strains (28%) carried sul1, and 3 strains (12%) carried sul3. Shoaib et al. [22] isolated 211 E. coli strains resistant to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole from a dairy farm environment in Xinjiang, China, and observed that 142 strains (67.3%) carried sul2, 59 strains (27.9%) carried sul1, and 38 strains (18.1%) carried sul3. Kuzeubayeva et al. [41] analyzed 207 samples of three types of cheese produced in Kazakhstan and observed that 31.4% of the cheese samples were contaminated with E. coli. The samples of soft cheese produced by small farms (80% of the samples) and packaged at the retail site (100%) showed the highest level of contamination. A total of 65 E. coli strains were isolated, of which 20 strains (30.8%) carried the sul1 gene.

It was observed that 68 E. coli strains (65.38%) out of the 104 isolates carried tetracycline resistance genes (Table 3). Among these, 58 E. coli strains (85.29%) harbored the tetA gene, with 22 E. coli strains (21.15%) carrying only this gene. Additionally, 46 E. coli strains (67.64%) carried the tetB gene, with only 10 E. coli strains (9.61%) carrying this gene exclusively. Finally, 36 E. coli strains (34.61%) simultaneously harbored both tetA and tetB genes. Regarding the phenotypic profile, 40 E. coli strains (38.46%) exhibited tetracycline resistance, while in the genotypic profile, 37 of the resistant E. coli strains (35.56%) carried the tetA and/or tetB genes. Therefore, 92.5% of E. coli strains resistant to tetracycline in the antibiogram carried the tetA and/or tetB genes. Additionally, among the 104 E. coli strains analyzed, 31 (29.80%) were susceptible to tetracycline in the antibiogram, but still carried the tetA and/or tetB genes.

Tetracycline resistance is widespread in E. coli from livestock, mainly mediated by efflux pumps encoded by tet genes. Among these, tetA and tetB are the most common, often carried on plasmids associated with mobile genetic elements such as transposons and integrons [42,43,44,45].

Several studies in the literature have reported the presence of tetA and tetB genes in E. coli isolated from raw milk and cheeses. Ombarak et al. [21] evaluated 61 E. coli isolates from 187 samples of raw milk and the two most popular cheeses in Egypt, all phenotypically resistant to tetracycline, and found that 53 strains (86.9%) carried the tetA gene, 9 (14.8%) carried tetB, 1 (1.63%) carried tetD, and none carried tetC. Shoaib et al. [22] analyzed 98 E. coli strains isolated from a large dairy farm in Xinjiang province, China, all phenotypically resistant to tetracycline, and found a higher presence of the tetB gene in 69 E. coli strains (70.4%), followed by tetA in 11 E. coli strains (11.2%), and no presence of the tetD gene. Belaynehe et al. [23] reported that 88 E. coli isolates (95.7%) from cattle farms, out of a total of 92 tetracycline-resistant isolates, carried tetracycline resistance genes. Among them, 47 E. coli isolates (51.1%) harbored the tetA gene, while 41 (44.6%) harbored tetB. Messele et al. [31] analyzed 16 E. coli strains isolated from raw milk samples from cows with mastitis at dairy farms in central Ethiopia and found that eight isolates (50.0%) carried the tetA gene. Tabaran et al. [46] isolated 27 enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and verotoxigenic E. coli (VTEC) strains from 120 raw milk samples and 80 unpasteurized cheese samples sold in Romania. Among these, 48.1% of E. coli strains (13/27) tested positive for tetracycline resistance genes. The tetA and tetB genes were identified in 38.5% of E. coli strains (5/13), tetC was identified in 30.8% (4/13), and 23.1% of E. coli strains (3/13) were positive for tetA, tetB, and tetC.

A notable finding in this study was the presence of β-lactam antimicrobial resistance genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV) in 58 E. coli strains (55.77%) (Table 3). However, lower resistance rates were observed in the phenotypic profile for the tested β-lactam antimicrobials: 19.23% (20/104) for amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 13.46% (14/104) for cefotaxime, and 10.58% (11/104) for ceftazidime. Thus, most E. coli strains (43.26%, 45/104) that carried β-lactam resistance genes were susceptible in the antibiogram. Meanwhile, 20 E. coli strains (19.23%) were resistant in the antibiogram to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and/or cefotaxime and/or ceftazidime and carried β-lactam antimicrobial resistance genes.

The most frequently detected β-lactam antimicrobial resistance gene in E. coli strains was blaCTX-M (21.15%, 22/104). Additionally, 14 E. coli strains (13.46%) simultaneously carried the blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes, while 10 (9.61%) harbored only the blaSHV gene. The blaTEM gene was found in nine strains (8.65%), whereas five (4.81%) carried all three genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV). Finally, three strains (2.88%) presented a combination of blaCTX-M and blaSHV genes, and another three (2.88%) carried a combination of blaSHV and blaTEM genes.

Gram-negative bacteria, especially species such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from the Enterobacteriaceae family, which produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), are among the main causes of resistance to β-lactam antimicrobials. ESBL-producing bacteria are resistant to penicillin and its derivatives, as well as first-, second-, and third-generation cephalosporins and monobactams. This resistance is mainly due to the production of CTX-M, TEM, and SHV β-lactamases, which are encoded by the bla-CTX-M, bla-SHV, and bla-TEM genes, respectively. The genes encoding ESBLs are frequently located on plasmids and housed within transposons, facilitating their spread among human and animal hosts. This phenomenon is a significant concern as it compromises the effectiveness of commonly used antimicrobials in the treatment of bacterial infections [47,48,49].

Several studies in the literature have reported a high prevalence of β-lactam antibiotic resistance genes in E. coli strains isolated from milk and dairy products. Shoaib et al. [22] isolated 263 E. coli strains resistant to cefotaxime from a dairy farm environment in Xinjiang, China, and observed that 148 strains (56.3%) carried the blaTEM gene, 68 (25.8%) carried blaOXA, and 59 (22.4%) carried blaCTX-M. Eldesoukey et al. [50] examined a total of 240 samples (75 from diarrheic calves, 150 from milk samples, and 15 from workers) for the prevalence of EPEC in three dairy farms in Egypt, and 28 EPEC isolates were detected. Among these 28 EPEC isolates, 5 strains (17.90%) carried the blaSHV gene, 3 (10.70%) carried both the blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes, 2 strains (7.10%) carried blaTEM, and 1 strain (3.60%) carried blaCTX-M, totaling 11 EPEC strains (39.30%) with the presence of the studied genes.

Ombarak et al. [21] reported that among 42 E. coli isolates resistant to ampicillin, obtained from 187 samples of raw milk and the two most popular cheeses in Egypt, 40 isolates (94.23%) carried the blaTEM gene, 9 (21.42%) carried blaCTX-M, and 3 (7.14%) carried blaSHV. In the same study, 10 E. coli isolates resistant to ampicillin were identified as ESBL producers, of which 9 (90.00%) carried the blaCTX-M gene, 8 (80.00%) carried blaTEM, and 1 (10.00%) carried blaSHV. Among these, five ESBL-producing isolates (50.00%) carried both the blaCTX-M and blaTEM genes. Tabaran et al. [46] reported that, out of 27 pathogenic E. coli strains isolated from 120 raw milk samples and 80 unpasteurized cheese samples sold in Romania, 33.3% (n = 9) carried the beta-lactamase gene blaTEM and none of the samples tested positive for blaSHV.

In this study, the cat1 and clmA genes (associated with resistance to phenicols) were detected in 23 E. coli isolates (22.12%), with only 2 strains (1.92%) being phenotypically resistant to chloramphenicol. Most of the strains (20.19%, 21/104) were phenotypically sensitive to chloramphenicol yet still carried resistance genes to phenicols (Table 3). It was observed that most of the E. coli strains carried the clmA gene (10/104, 17.31%), while 4 E. coli (3.85%) carried cat1, and 1 (0.96%) carried both cat1 and clmA.

Phenicols are broad-spectrum antimicrobials commonly used in veterinary practice. Due to the severe toxicity of chloramphenicol, which can lead to life-threatening blood disorders such as irreversible aplastic anemia, hypoplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and granulocytopenia, its use in food-producing animals was prohibited in the European Union in 1994 and in Brazil in 2003. However, the fluorinated derivative florfenicol remains approved for treating bacterial infections in livestock [14,51].

A total of 60 genotypic antimicrobial resistance patterns of E. coli isolates were identified (Table 4), representing 80.77% of the isolated E. coli strains (84/104). The most frequent genotypic antimicrobial resistance patterns were blaCTX-M–sul1–tetA–tetB–blaTEM, observed in 4.81% of the strains (5/104), and sul1–tetA–tetB, observed in 3.85% of the strains (4/104).

Table 4.

Genotypic antimicrobial resistance patterns of Escherichia coli isolates.

In the present study, seven E. coli strains were found to exhibit a resistant phenotype without carrying any of the resistance genes investigated. These strains likely harbor other antimicrobial resistance genes not included in the current analysis. On the other hand, several E. coli isolates did not show resistance in the antibiogram but expressed resistance genes in PCR. Recent studies have been published referring to these genes as ‘silent genes’ [16,17,18,19,20].

Silent genes are DNA sequences that are usually inactive or expressed at very low levels but can be activated by mutations, recombination, or transfer to a new host [16]. Some genes may appear silent in the laboratory yet are expressed in natural environments. Like other genes, silent genes can spread via horizontal gene transfer. Studying the full resistome, including silent genes, is crucial for understanding antibiotic resistance, as both resistant and phenotypically susceptible strains should be considered [16,17,18,19,20].

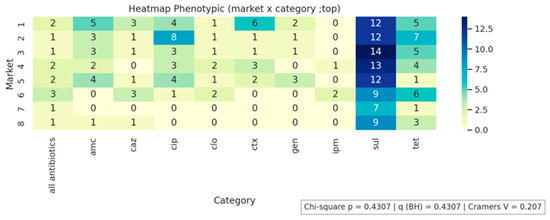

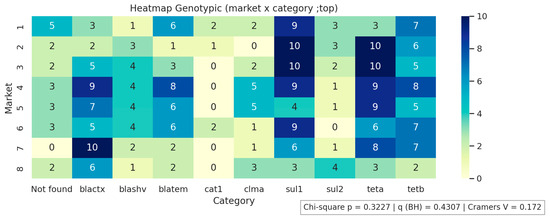

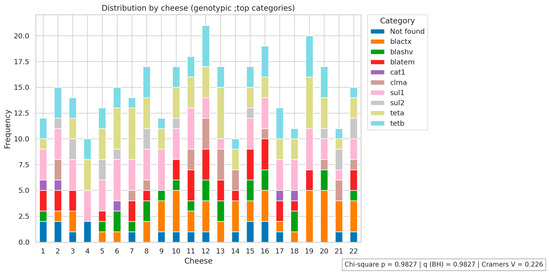

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the analyses of phenotypic and genotypic resistance categories across markets and, consequently, cheese samples. The associations between markets and phenotypic (Figure 1) and genotypic (Figure 2) resistance categories were weak, with small effect sizes and non-significant chi-square values (p = 0.43 and p = 0.32, respectively), indicating that resistance profiles were broadly distributed among the markets and their corresponding cheese samples, without apparent geographical differences in antimicrobial resistance patterns. The distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes across cheese samples (Figure 3) also showed limited evidence of dependence (p = 0.98), suggesting that resistance genes were not clustered in specific markets or cheese samples. Overall, these results indicate that phenotypic and genotypic resistance traits are dispersed across the sampled markets, and there is no significant concentration of resistance patterns in particular locations or products.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic resistance distribution across markets.

Figure 2.

Genotypic resistance distribution across markets. Not found indicates that none of the investigated genes were detected.

Figure 3.

Antimicrobial resistance genes distribution across cheese samples. Not found indicates that none of the investigated genes were detected.

All antibiotics indicates susceptibility to all tested antibiotics. AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CLO, chloramphenicol; CTX, Cefotaxime; GEN, gentamicin; IMP, imipenem; SUL, sulfonamide; TET, tetracycline

Minas frescal cheese has intrinsic factors, such as high moisture, neutral pH, and nutrient richness, which favor bacterial growth. This, combined with the use of raw milk in its production, results in a high level of contamination with potentially pathogenic bacteria, including E. coli. The situation is further aggravated by the presence of both genotypic and phenotypic antimicrobial resistance in these bacteria. Therefore, it is essential to implement educational programs for small-scale artisanal cheese producers, emphasizing the prohibition of using raw milk in the production of fresh cheeses, and strengthening market surveillance of these products. Such measures are fundamental to improving food safety and protecting consumers from potential health risks associated with the consumption of these cheeses [7,8,10,11,12].

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

A total of 22 samples of artisanal Minas Frescal cheese were collected from 8 different farmers’ markets in the Federal District, Brazil, between February 2022 and March 2024, with 2 to 3 samples from different vendors collected at each market. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory in a thermal box containing ice, and microbiological analyses began a maximum of one hour after collection. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, meaning three aliquots were taken from each package, and the results were expressed as means and standard deviations.

3.2. Enumeration of Thermotolerant Coliforms and Isolation of E. coli

Enumeration of thermotolerant coliforms and isolation of E. coli were performed according to the methods described by Feng et al. [52]. For the analysis, 25 g of each sample was weighed and diluted in 225 mL of 0.1% peptone water (w/v). The material was homogenized, resulting in the first dilution (10−1). Subsequent decimal dilutions (up to 10−3) were prepared from this initial dilution. The determination of the Most Probable Number (MPN) of thermotolerant coliforms was conducted using the multiple-tube fermentation technique, starting with the presumptive test. This involved inoculating each sample dilution into Lauryl Sulfate Tryptose Broth (HiMedia, Thane, India). The tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. A positive result was indicated by turbidity in the broth accompanied by gas production in the Durham tubes. Aliquots from the positive tubes in the presumptive test were inoculated into tubes containing Escherichia coli broth (EC broth, Kasvi, Madrid, Spain) to confirm the presence of thermotolerant coliforms. The tubes were incubated in a water bath at 45 °C for 24 h. Again, a positive result was indicated by turbidity accompanied by gas production. The results were expressed as log MPN/g. For the isolation of E. coli, aliquots of the EC broth were streaked onto MacConkey Agar (HiMedia, Thane, India), and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, 6 strains suspected of being E. coli (strongly lactose-fermenting colonies) were isolated from each sample, each presenting distinct antibiograms, totaling 132 suspected strains. These strains were subjected to molecular identification using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique to confirm the presence of E. coli. After genetic identification, 104 strains were confirmed as E. coli. The uidA gene was not amplified in 28 strains; therefore, these strains were discontinued.

3.3. Bacterial DNA Extraction

The isolated bacterial colonies were cultured in Mueller–Hinton broth (Kasvi Madrid, Spain) for 18–24 h. Then, DNA extraction was performed using the Purelink Genomic DNA Mini Kit Invitrogen™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol for Gram-negative bacteria. The quality of the extracted DNA was assessed via electrophoresis on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel, and the DNA concentration was quantified using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The DNA products were diluted with Milli-Q water to an average concentration of 20 ng/μL.

3.4. Identification of E. coli

For the identification of E. coli, the uidA gene, which encodes the enzyme β-glucuronidase, and the lacZB gene, which encodes the enzyme β-galactosidase, were used as characteristic markers of the species [27]. The primers sequences are detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Primers sequences and amplified product sizes for the identification of Escherichia coli.

For the uidA gene, the PCR thermocycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. For the lacZB gene, the PCR thermocycling conditions were initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. Gene fragment amplification was carried out using the following thermocyclers: Life Express Thermal Cycler, model TC-96/G/H(b); Swift MiniPro Thermal Cycler, model SWT-MIP-0-2-1; and Life Touch Thermal Cycler, model TC-96/G/H(b)B. The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on 2% (w/v) agarose gel (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), stained with ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), at a power setting of 50 W. The results were visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light using a 100 bp DNA ladder molecular weight marker (Ludwig Biotecnologia, Porto Alegre, Brazil).

3.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of E. coli

The antimicrobial susceptibility test for E. coli strains was performed using the standard Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method [53]. The bacterial inoculum was prepared by a direct suspension of microbial growth in Mueller–Hinton broth, adjusted to a turbidity equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard. The microbial inoculum was spread uniformly on the surface of a Mueller–Hinton agar plate using a sterile swab. After the inoculum dried, antimicrobial agent disks were applied. Results were obtained after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C by measuring the inhibition zone diameters in millimeters. The antimicrobials and reference values for interpreting inhibition zones are detailed in Table 6. E. coli showing resistance to three or more antimicrobial agents from different classes were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR).

Table 6.

Antimicrobials, concentrations used, and reference values for the interpretation of inhibition zones in the antimicrobial susceptibility test for Escherichia coli.

Antimicrobial drugs were selected based on different classes and their importance for veterinary use (mainly in dairy cattle farming) and/or their relevance for human medicine. Thus, the drugs with the highest veterinary use include tetracyclines followed by the penicillin class (such as amoxicillin combined with clavulanic acid), the phenicol class (although chloramphenicol is banned, the fluorinated derivative florfenicol is licensed for the treatment of bacterial infections in food-producing animals), and the sulfonamide class (sulfonamides). On the other hand, the use of drugs such as ciprofloxacin (quinolones) and cefotaxime and ceftazidime (cephalosporins) in animal disease treatment is more restricted and controlled due to their critical importance in human medicine [54,55]. Although gentamicin (aminoglycoside) is permitted for veterinary use in Brazil, as in human medicine, its use is limited due to the risk of toxicity [56,57]. Finally, imipenem (carbapenem) is prohibited for use in animal treatment due to its critical importance in human medicine, where it is considered a last-resort antibiotic [58].

3.6. Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in E. coli

All 104 E. coli strains were examined for the presence of the following antimicrobial resistance genes: sul1 and sul2 (resistance to sulfonamides); tetA and tetB (resistance to tetracyclines); blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV (resistance to β-lactams); and cat1 and clmA (resistance to chloramphenicol). The primer sequences and PCR conditions are described in Table 7. Gene amplification was carried out using the following thermocyclers: Life Express Thermal Cycler, model TC-96/G/H(b); Swift MiniPro Thermal Cycler, model SWT-MIP-0-2-1; and Life Touch Thermal Cycler, model TC-96/G/H(b)B. For agarose gel electrophoresis, 8 microliters of the PCR amplification products, supplemented with 2 µL of bromophenol blue (Dinâmica Química, São Paulo, Brazil), was subjected to separation using 2% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) under a constant voltage of 50 V. The DNA fragments were stained with ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich-Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light. A 100 bp marker (Ludwig Biotecnologia, Porto Alegre, Brazil) was used as a molecular weight reference standard.

Table 7.

Primer sequences for the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in Escherichia coli and PCR conditions.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

To investigate potential associations between phenotypic and genotypic resistance categories across markets and cheeses, chi-square tests of independence were performed on the main categories. Cramér’s V was computed to estimate effect sizes, and p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. The analyses indicated associations between market and resistance categories, as well as patterns of phenotypic and genotypic resistance distribution across cheeses. Statistical analyses were conducted in Python (version 3.11; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA).

4. Conclusions

In this study, a total of 104 E. coli strains were isolated from 22 samples of artisanal Minas Frescal cheese, with the highest rates of phenotypic antimicrobial resistance observed for sulfonamides (85.58%, 89/104) and tetracyclines (38.46%, 40/104). In the genotypic profiles, most E. coli isolates carried the sulfonamide resistance genes sul1 and/or sul2 (62.50%, 65/104), the tetracycline resistance genes tetA and/or tetB (65.38%, 68/104), and the β-lactam resistance genes blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and/or blaSHV (55.77%, 58/104). The high prevalence of E. coli strains exhibiting both phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance in artisanal Minas Frescal cheese raises public health concerns due to the potential dissemination of these resistance determinants through the food chain. These findings highlight the need for stricter regulation and more effective oversight of the production and commercialization processes of these artisanal cheeses, as well as the implementation of educational strategies for producers regarding the microbiological risks associated with these products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.F.S.R., I.C.R.d.S. and D.C.O.; methodology and validation: L.F.S.R., R.A.d.M., N.M.B., D.C.O. and I.C.R.d.S.; investigation and formal analysis: L.F.S.R., R.A.d.M., N.M.B., A.C.S.A., M.O.d.A., R.D.d.S., C.A.B., K.O.G., B.A.d.P.; writing—original draft preparation: D.C.O. and L.F.S.R.; writing—review and editing: D.C.O.; I.C.R.d.S. and L.C.L.d.S.B.; Supervision: I.C.R.d.S., L.C.L.d.S.B. and D.C.O.; funding acquisition: D.C.O., L.C.L.d.S.B. and I.C.R.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly financed by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior- Brasil (CAPES), Finance Code 001 for the scholarships; and FAPDF (Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy interests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carneiro Aguiar, R.A.; Ferreira, F.A.; Dias, R.S.; Nero, L.A.; Miotto, M.; Verruck, S.; De Marco, I.; De Dea Lindner, J. Graduate student literature review: Enterotoxigenic potential and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococci from Brazilian artisanal raw milk cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5685–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C. Brazil: Dairy and Products Annual USDA. 2023. Available online: https://fas.usda.gov/data/brazil-dairy-and-products-annual-10 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Siqueira, K.B. Na Era do Consumidor: Uma Visão do Mercado Lácteo Brasileiro; Edição do Autor: Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil, 2021; 220p, Available online: http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1134890 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Rocha, R.S.; Silva, R.; Guimarães, J.T.; Balthazar, C.F.; Pimentel, T.C.; Neto, R.P.C.; Tavares, M.I.B.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q.; Cappato, L.P.; et al. Possibilities for using ohmic heating in Minas Frescal cheese production. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 109027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado Comum do Sul. Instrução Normativa n° 4, de 1 de Março de 2004. Technical Regulation on Minas Frescal Cheese—Standards of Identity and Quality. 2004. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/defesa-agropecuaria/suasa/regulamentos-tecnicos-de-identidade-e-qualidade-de-produtos-de-origem-animal-1/rtiq-leite-e-seus-derivados (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Teider, P.I.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Ossugui, E.H.; Tamanini, R.; Ribeiro, J.; Santos, G.A.; Alfieri, A.A.; Beloti, V. Pseudomonas spp. and other psychrotrophic microorganisms in inspected and non-inspected Brazilian Minas Frescal Cheese: Proteolytic, lipolytic and AprX production potential. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2019, 39, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos, A.C.L.P.; Puño-Sarmiento, J.J.; Medeiros, L.P.; Gazal, L.E.S.; Maluta, R.P.; Navarro, A.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Fagan, E.P.; Nakazato, G. Virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli from cheese made from unpasteurized milk in Brazil. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018, 15, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.C.; de Araújo, J.P.A.; Fusieger, A.; de Carvalho, A.F.; Nero, L.A. Microbiological quality and safety of Brazilian artisanal cheeses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, M.V.; Nespolo, N.; Delfino, T.C.; Almeida, C.C.; Pizauro, L.J.L.; Valmorbida, M.K.; Pereira, N.; Ávila, F.A. Raw milk cheese as a potential infection source of pathogenic and toxigenic foodborne pathogens. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, R.H.R.; Freitas, F.; Castro, B.G. Hygienic-sanitary quality and antimicrobial sensitivity profile of Escherichia coli in milk and cheese sold illegally in municipalities of northern Mato Grosso, Brazil. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2021, 88, e0702019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.D.; Santos, I.G.; Dias, B.P.; Nascimento, C.A.; Rodrigues, É.M.; Ribeiro Júnior, J.C.; Alfieri, A.A.; Alexandrino, B. Hygienic-health quality and microbiological hazard of clandestine Minas Frescal cheese commercialized in north Tocantins, Brazil. Semin. Cienc. Agrar. 2021, 42, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A.P.A.; Campos, G.Z.; Pimentel-Filho, N.J.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Pinto, U.M. Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses: Diversity, Microbiological Safety, and Challenges for the Sector. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 666922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakbin, B.; Brück, W.M.; Rossen, J.W.A. Virulence factors of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Madec, J.Y.; Lupo, A.; Schink, A.K.; Kieffer, N.; Nordmann, P.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Shen, Y.; Qu, D.; Han, J. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and characteristics of integrons in Escherichia coli strains isolated from a large-scale centralized swine slaughterhouse and its downstream markets in Zhejiang, China. Food Control 2019, 95, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, M.; Mackiw, E.; Kowalska, J.; Kucharek, K.; Postupolski, J. Silent genes: Antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic production. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipszyc, A.; Szuplewska, M.; Bartosik, D. How do transposable elements activate expression of transcriptionally silent antibiotic resistance genes? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Dong, W.; Hu, X.; Xie, C.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Lu, Y.; You, X. Silent or low expression of blaTEM and blaSHV suggests potential for targeted proteomics in clinical detection of β-lactamase-related antimicrobial resistance. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deekshit, V.K.; Srikumar, S. ‘To be, or not to be’—The dilemma of ‘silent’ antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2902–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vk, D.; Srikumar, S.; Shetty, S.; Van Nguyen, S.; Karunasagar, I.; Fanning, S. Silent antibiotic resistance genes: A threat to antimicrobial therapy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 79, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombarak, R.A.; Hinenoya, A.; Elbagory, A.M.; Yamasaki, S. Prevalence and molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from raw milk and raw milk cheese in Egypt. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; He, Z.; Geng, X.; Tang, M.; Hao, R.; Wang, S.; Shang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Pu, W. The emergence of multi-drug resistant and virulence gene carrying Escherichia coli strains in the dairy environment: A rising threat to the environment, animal, and public health. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1197579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaynehe, K.M.; Shin, S.W.; Yoo, H.S. Interrelationship between tetracycline resistance determinants, phylogenetic group affiliation and carriage of class 1 integrons in commensal Escherichia coli isolates from cattle farms. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Instrução Normativa N° 161, 1 de Julho de 2022. Establishes the Microbiological Standards for Food. 2022. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-in-n-161-de-1-de-julho-de-2022-413366880 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Mohamed, M.-Y.I.; Habib, I. Pathogenic E. coli in the food chain across the Arab countries: A descriptive review. Foods 2023, 12, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbau-Piednoir, E.; Denayer, S.; Botteldoorn, N.; Dierick, K.; De Keersmaecker, S.C.J.; Roosens, N.H. Detection and discrimination of five E. coli pathotypes using a combinatory SYBR® Green qPCR screening system. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3267–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, F.; López-Acedo, E.; Tabla, R.; Roa, I.; Gómez, A.; Rebollo, J.E. Improved detection of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria by multiplex PCR. BMC Biotechnol. 2015, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei Ahmady, A.; Aliyan Aliabadi, R.; Amin, M.; Ameri, A.; Abbasi Montazeri, E. Occurrence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli pathotypes from raw milk and unpasteurized buttermilk by culture and multiplex polymerase chain reaction in southwest Iran. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 3661–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanjary, L.H.; Sheet, O.H. Molecular detection of uidA gene in Escherichia coli isolated from the dairy farms in Nineveh governorate, Iraq. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 2022, 36, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.F.; Rossi, G.A.M.; Sato, R.A.; de Souza Pollo, A.; Cardozo, M.V.; Amaral, L.A.; Fairbrother, J.M. Epidemiology, virulence and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from small Brazilian farms producers of raw milk fresh cheese. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messele, Y.E.; Abdi, R.D.; Tegegne, D.T.; Bora, S.K.; Babura, M.D.; Emeru, B.A.; Weird, G.M. Analysis of milk-derived isolates of E. coli indicating drug resistance in central Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 51, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.A.; Shaker, E.M. Investigation of the effect of chitosan and silver nanoparticles on the antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated from some milk products and diarrheal patients in Sohag city, Egypt. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joubrane, K.; Jammoul, A.; Daher, R.; Ayoub, S.; El Jed, M.; Hneino, M.; El Hawari, K.; Al Iskandarani, M.; Daher, Z. Microbiological contamination, antimicrobial residues, and antimicrobial resistance in raw bovine milk in Lebanon. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 134, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/cvm-updates/fda-releases-annual-summary-report-antimicrobials-sold-or-distributed-2021-use-food-producing (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Kasem, N.G.; Al-Ashmawy, M.; Elsherbini, M.; Abdelkhalek, A. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular genotyping of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from some Egyptian cheeses. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, N.D.; Hassan, J.W.; Osman, M.; El-Omari, K.; Kharroubi, S.A.; Toufeili, I.; Kassem, I.I. Assessment of the microbiological acceptability of white cheese (Akkawi) in Lebanon and the antimicrobial resistance profiles of associated Escherichia coli. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzitey, F.; Yussif, S.; Ayamga, R.; Zuberu, S.; Addy, F.; Adu-Bonsu, G.; Huda, N.; Kobun, R. Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characterization of Escherichia coli recovered from milk and related samples. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Dong, Y.; Jiao, X.; Tang, B.; Feng, T.; Li, P.; Fang, J. In vivo fitness of sul gene-dependent sulfonamide-resistant Escherichia coli in the mammalian gut. mSystems 2024, 9, e0083624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Santos, E.; Laviña, M.; Poey, M.E. Strict relationship between class 1 integrons and resistance to sulfamethoxazole in Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 161, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Osuna, M.; Cortés, P.; Barbé, J.; Erill, I. Origin of the mobile di-hydro-pteroate synthase gene determining sulfonamide resistance in clinical isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzeubayeva, A.; Ussenbayev, A.; Aydin, A.; Akanova, Z.; Rychshanova, R.; Abdullina, E.; Seitkamzina, D.; Sakharia, L.; Ruzmatov, S. Contamination of Kazakhstan cheeses originating from Escherichia coli and its resistance to antimicrobial drugs. Vet. World 2024, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S. Tetracycline and phenicol resistance genes and mechanisms: Importance for agriculture, the environment, and humans. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, T.H. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perewari, D.O.; Otokunefor, K.; Agbagwa, O.E. Tetracycline-resistant genes in Escherichia coli from clinical and nonclinical sources in rivers state, Nigeria. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 9192424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, T.S.B.; Overgaard, M.; Nielsen, S.S.; Bortolaia, V.; Sommer, M.O.A.; Guardabassi, L.; Olsen, J.E. Relation between tetR and tetA expression in tetracycline resistant Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaran, A.; Mihaiu, M.; Tăbăran, F.; Colobatiu, L.; Reget, O.; Borzan, M.M.; Dan, S.D. First study on characterization of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in verotoxigenic and enterotoxigenic E. coli isolated from raw milk and unpasteurized traditional cheeses in Romania. Folia Microbiol. 2017, 62, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, L.; Loayza, F.; Cárdenas, P.; Saraiva, C.; Johnson, T.J.; Amato, H.; Graham, J.P.; Trueba, G. Environmental spread of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli and ESBL genes among children and domestic animals in Ecuador. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 27007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastidas-Caldes, C.; Romero-Alvarez, D.; Valdez-Vélez, V.; Morales, R.D.; Montalvo-Hernández, A.; Gomes-Dias, C.; Calvopiña, M. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Escherichia coli in South America: A systematic review with a one health perspective. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 5759–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; Bradford, P.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: An update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldesoukey, I.E.; Elmonir, W.; Alouffi, A.; Beleta, E.I.M.; Kelany, M.A.; Elnahriry, S.S.; Alghonaim, M.I.; alZeyadi, Z.A.; Elaadli, H. Multidrug-resistant enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from diarrhoeic calves, milk, and workers in dairy farms: A potential public health risk. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Instrução Normativa MAPA n° 09, de 27 de Junho de 2003. The Manufacture, Handling, Splitting, Marketing, Importation, and Use of the Active Ingredient’s Chloramphenicol and Nitrofurans, as Well as Any Products Containing These Substances, Are Prohibited for Veterinary Use and for Any Use in the Feeding of All Animals and Insects. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/insumos-agropecuarios/insumos-pecuarios/resistencia-aos-antimicrobianos/legislacao/proibicoes-de-aditivos-na-alimentacao-animal (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Feng, P.; Weagant, S.D.; Grant, M.A.; Burkhardt, W. Chapter 4: Enumeration of Escherichia coli and the Coliform bacteria. In Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM); FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-4-enumeration-escherichia-coli-and-coliform-bacteria (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. M02 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 14th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Organization for Animal Health. Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents Intended for Use in Animals, 8th ed.; World Organization for Animal Health: Paris, France, 2024; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Virto, M.; Santamarina-García, G.; Amores, G.; Hernández, I. Antibiotics in dairy production: Where is the problem? Dairy 2022, 3, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.A.; Hiba, T.; Chaudhari, D.; Preston, A.N.; Palowsky, Z.R.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.D. Aminoglycoside-related nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity in clinical practice: A review of pathophysiological mechanism and treatment options. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, D.A.P.; Costa, F.N. Antimicrobial resistance of bacterial agents of bovine mastitis from dairy properties in the metropolitan region of São Luís—MA. Rev. Bras. Saúde Prod. Anim. 2024, 25, e20230033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/1255 of 19 May 2022 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council by establishing the criteria for the designation of antimicrobials to be reserved for the treatment of certain infections in humans. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, 20, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Guo, H.; Sun, S. Molecular and phenotypic characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from farmed minks in Zhucheng, China. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3917841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, H.; Pakzad, I.; Nasrollahi, A.; Hosainzadegan, H.; Azizi Jalilian, F.; Taherikalani, M.; Samadi, N.; Monadi Sefidan, A. Sulfonamide resistance genes (sul) M in extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) and non-ESBL producing Escherichia coli Isolated from Iranian hospitals. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2015, 8, e19961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.O.; Clegg, P.D.; Williams, N.J.; Baptiste, K.E.; Bennett, M. Antimicrobial resistance in equine faecal Escherichia coli isolates from North West England. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2010, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, D.A.; Tyler, S.; Christianson, S.; McGeer, A.; Muller, M.P.; Willey, B.M.; Bryce, E.; Gardam, M.; Nordmann, P.; Mulvey, M.R. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 92-kilobase plasmid harboring the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase involved in an outbreak in long-term-care facilities in Toronto, Canada. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3758–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundran, R.S.; Cardenio, P.A.; Villanueva, M.A.; Sison, F.B.; Benigno, C.C.; Kreausukon, K.; Pichpol, D.; Punyapornwithaya, V. Prevalence and distribution of blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEM genes in extended- spectrum β- lactamase- producing E. coli isolates from broiler farms in the Philippines. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van, T.T.; Chin, J.; Chapman, T.; Tran, L.T.; Coloe, P.J. Safety of raw meat and shellfish in Vietnam: An analysis of Escherichia coli isolations for antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 124, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).