Insights into the Rising Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Epidemic Infections in Eastern Europe: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Diagnostic Methods

2.2. Epidemiology and Antibiotic Susceptibility of CRE

2.3. Carbapenem-Resistant P. aeruginosa Susceptibility to Antibiotics and Resistance Mechanisms

3. Discussion

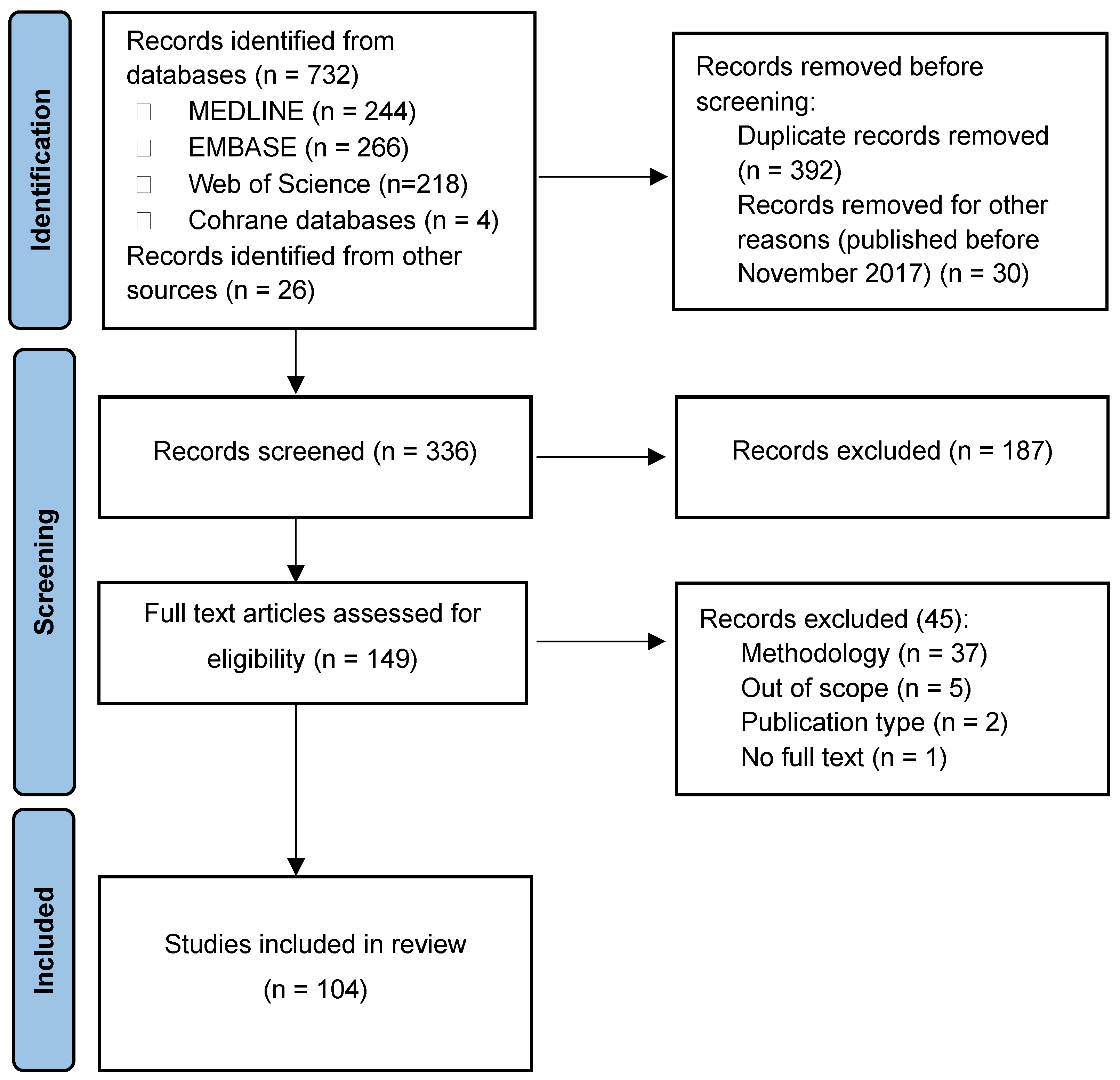

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Literature Search

4.2. Inclusion Criteria

4.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations; The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Mestrovic, T.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Ikuta, K.S.; Gray, A.P.; Davis Weaver, N.; Han, C.; Wool, E.E.; Gershberg Hayoon, A.; Hay, S.I.; et al. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: A cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e897–e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, K.S.; Pogue, J.M. Infections Caused by Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Epidemiology and Management. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua-García, M.; Bravo-Ferrer, J.M.; Pérez-Galera, S.; Kostyanev, T.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Feifel, J.; Palacios-Baena, Z.R.; Schotsman, J.; Cantón, R.; Daikos, G.L.; et al. Attributable mortality of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales: Results from a prospective, multinational case-control-control matched cohorts study (EURECA). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Blaser, M.; Guidos, R.J.; Boucher, H.W.; Bradley, J.S.; Eisenstein, B.I.; Gerding, D.; Lynfield, R.; Reller, L.B.; Rex, J.; et al. Combating antimicrobial resistance: Policy recommendations to save lives. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl. S5), S397–S428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurilio, C.; Sansone, P.; Barbarisi, M.; Pota, V.; Giaccari, L.G.; Coppolino, F.; Barbarisi, A.; Passavanti, M.B.; Pace, M.C. Mechanisms of Action of Carbapenem Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suay-García, B.; Pérez-Gracia, M.T. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, H.; Glasner, C.; Albiger, B.; Aanensen, D.M.; Tomlinson, C.T.; Andrasević, A.T.; Cantón, R.; Carmeli, Y.; Friedrich, A.W.; Giske, C.G.; et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): A prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, M.; Kavvada, A.; Kavvadas, D.; Kyriazidi, M.A.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Varlamis, S.; Papaliagkas, V.; Mitka, S. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Balkans: Clonal distribution and associated resistance determinants. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2024, 71, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe 2023–2021 Data; Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and World Health Organization: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Fritzenwanker, M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Herold, S.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Zimmer, K.P.; Chakraborty, T. Treatment Options for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2018, 115, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Carrara, E.; Retamar, P.; Tängdén, T.; Bitterman, R.; Bonomo, R.A.; de Waele, J.; Daikos, G.L.; Akova, M.; Harbarth, S.; et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European society of intensive care medicine). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 521–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drugs.com. Recarbrio FDA Approval History. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/history/recarbrio.html (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Lob, S.H.; Hawser, S.P.; Siddiqui, F.; Alekseeva, I.; DeRyke, C.A.; Young, K.; Motyl, M.R.; Sahm, D.F. Activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam and imipenem/relebactam against clinical gram-negative isolates from Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland-SMART 2017–2020. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlowsky, J.A.; Lob, S.H.; Hawser, S.P.; Kothari, N.; Siddiqui, F.; Alekseeva, I.; DeRyke, C.A.; Young, K.; Motyl, M.R. Activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam and imipenem/relebactam against clinical isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa collected in Greece and Italy: SMART 2017–2021. In Proceedings of the 33rd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 April 2023. Poster P0194. [Google Scholar]

- Baraniak, A.; Machulska, M.; Żabicka, D.; Literacka, E.; Izdebski, R.; Urbanowicz, P.; Bojarska, K.; Herda, M.; Kozińska, A.; Hryniewicz, W.; et al. Towards endemicity: Large-scale expansion of the NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 lineage in Poland, 2015–2016. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3199–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedrzycka, M.; Izdebski, R.; Urbanowicz, P.; Polańska, M.; Hryniewicz, W.; Gniadkowski, M.; Literacka, E. MDR carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of the hypervirulence-associated ST23 clone in Poland, 2009–2019. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 3367–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedrzycka, M.; Urbanowicz, P.; Żabicka, D.; Hryniewicz, W.; Gniadkowski, M.; Izdebski, R. Country-wide expansion of a VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella oxytoca ST145 lineage in Poland, 2009–2019. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauncajs, M.; Bielec, F.; Macieja, A.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Fermenting and Non-Fermenting Rods Isolated from Hospital Patients in Poland-What Are They Susceptible to? Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauncajs, M.; Bielec, F.; Macieja, A.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline against Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacilli Clinical Isolates in Central Poland. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celejewski-Marciniak, P.; Wolinowska, R.; Wróblewska, M. Molecular Characterization of Class 1, 2 and 3 Integrons in Serratia spp. Clinical Isolates in Poland-Isolation of a New Plasmid and Identification of a Gene for a Novel Fusion Protein. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 4601–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielarczyk, A.; Pomorska-Wesołowska, M.; Romaniszyn, D.; Wójkowska-Mach, J. Healthcare-Associated Laboratory-Confirmed Bloodstream Infections-Species Diversity and Resistance Mechanisms, a Four-Year Retrospective Laboratory-Based Study in the South of Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, A.; Rybicki, Z.; Tomaszewski, D. An Analysis of the Type and Antimicrobial Resistance of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolated at the Military Institute of Medicine in Warsaw. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2019, 12, e67823. [Google Scholar]

- Guzek, A.; Rybicki, Z.; Woźniak-Kosek, A.; Tomaszewski, D. Bloodstream Infections in the Intensive Care Unit: A Single-Center Retrospective Bacteriological Analysis Between 2007 and 2019. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Mączyńska, B.; Rurańska-Smutnicka, D.; Secewicz, A.; Krochmal, G.; Bartelak, M.; Górzyńska, A.; Laufer, K.; Woronowicz, K.; Łubniewska, J.; et al. Assessment of the Susceptibility of Clinical Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacterial Strains to Fosfomycin and Significance of This Antibiotic in Infection Treatment. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuch, A.; Zieniuk, B.; Żabicka, D.; Van de Velde, S.; Literacka, E.; Skoczyńska, A.; Hryniewicz, W. Activity of temocillin against ESBL-, AmpC-, and/or KPC-producing Enterobacterales isolated in Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mączyńska, B.; Jama-Kmiecik, A.; Sarowska, J.; Woronowicz, K.; Choroszy-Król, I.; Piątek, D.; Frej-Mądrzak, M. Changes in Antibiotic Resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates in a Multi-Profile Hospital in Years 2017–2022 in Wroclaw, Poland. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowiec, P.; Klesiewicz, K.; Małek, M.; Skiba-Kurek, I.; Sowa-Sierant, I.; Skałkowska, M.; Budak, A.; Karczewska, E. Antimicrobial susceptibility and prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from pediatric and adult patients of two Polish hospitals. New Microbiol. 2019, 42, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ochońska, D.; Klamińska-Cebula, H.; Dobrut, A.; Bulanda, M.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M. Clonal Dissemination of KPC-2, VIM-1, OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 in Katowice, Poland. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojdana, D.; Gutowska, A.; Sacha, P.; Majewski, P.; Wieczorek, P.; Tryniszewska, E. Activity of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Alone and in Combination with Ertapenem, Fosfomycin, and Tigecycline Against Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, I.; Ziółkowski, G.; Jachowicz-Matczak, E.; Stasiowski, M.; Gajda, M.; Wójkowska-Mach, J. Colonization and Healthcare-Associated Infection of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Data from Polish Hospital with High Incidence of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Does Active Target Screening Matter? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletajew, S.; Pawlik, K.; Bonder-Nowicka, A.; Pakuszewski, A.; Nyk, Ł.; Kryst, P. Multi-Drug Resistant Bacteria as Aetiological Factors of Infections in a Tertiary Multidisciplinary Hospital in Poland. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruss, A.; Kwiatkowski, P.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Masiuk, H.; Łapińska, A.; Kot, B.; Kilczewska, Z.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S.; Dołęgowska, B. Similarity Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae Producing Carbapenemases Isolated from UTI and Other Infections. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarowska, J.; Choroszy-Krol, I.; Jama-Kmiecik, A.; Mączyńska, B.; Cholewa, S.; Frej-Madrzak, M. Occurrence and Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains Isolated from Hospitalized Patients in Poland—A Single Centre Study. Pathogens 2022, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sękowska, A.; Chudy, M.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E. Emergence of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Poland. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2019, 67, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sękowska, A.; Grabowska, M.; Bogiel, T. Satisfactory In Vitro Activity of Ceftolozane-Tazobactam against Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa But Not against Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates. Medicina 2023, 59, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefaniuk, E.M.; Kozińska, A.; Waśko, I.; Baraniak, A.; Tyski, S. Occurrence of Beta-Lactamases in Colistin-Resistant Enterobacterales Strains in Poland—A Pilot Study. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, P.; Izdebski, R.; Baraniak, A.; Żabicka, D.; Hryniewicz, W.; Gniadkowski, M. Molecular and genomic epidemiology of VIM/IMP-like metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa genotypes in Poland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanke-Rytt, M.; Sobierajski, T.; Lachowicz, D.; Seliga-Gąsior, D.; Podsiadły, E. Analysis of Etiology of Community-Acquired and Nosocomial Urinary Tract Infections and Antibiotic Resistance of Isolated Strains: Results of a 3-Year Surveillance (2020–2022) at the Pediatric Teaching Hospital in Warsaw. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalas-Więcek, P.; Michalska-Foryszewska, A.; Polak, A.; Orczykowska-Kotyna, M.; Pojnar, Ł.; Zając, M.; Patzer, J.; Głowacka, E.; Bogiel, M. Aktywność ceftazydymu z awibaktamem oraz innych antybiotyków stosowanych wobec Enterobacterales i Pseudomonas aeruginosa w Polsce w oparciu o dane z programu ATLAS zebrane w 2020 r. oraz porównanie ich z danymi uzyskanymi w latach 2015–2019. Forum Zakażeń 2022, 13, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalas-Więcek, P.; Prażyńska, M.; Pojnar, Ł.; Pałka, A.; Żabicka, D.; Orczykowska-Kotyna, M.; Polak, A.; Możejko-Pastewka, B.; Głowacka, E.A.; Pieniążek, I.; et al. Ceftazidime/Avibactam and Other Commonly Used Antibiotics Activity Against Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated in Poland in 2015–2019. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolayan, A.O.; Rigatou, A.; Grundmann, H.; Pantazatou, A.; Daikos, G.; Reuter, S. Three Klebsiella pneumoniae lineages causing bloodstream infections variably dominated within a Greek hospital over a 15 year period. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, 001082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, S.S.; Legakis, N.J.; Skalidis, T.; Loannidis, A.; Goumenopoulos, C.; Joshi, P.R.; Shrivastava, R.; Palwe, S.R.; Periasamy, H.; Patel, M.V.; et al. In vitro activity of cefepime/zidebactam (WCK 5222) against recent Gram-negative isolates collected from high resistance settings of Greek hospitals. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 100, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzidimitriou, M.; Chatzivasileiou, P.; Sakellariou, G.; Kyriazidi, M.; Kavvada, A.; Chatzidimitriou, D.; Chatzopoulou, F.; Meletis, G.; Mavridou, M.; Rousis, D.; et al. Ceftazidime/avibactam and eravacycline susceptibility of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in two Greek tertiary teaching hospitals. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2021, 68, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galani, I.; Antoniadou, A.; Karaiskos, I.; Kontopoulou, K.; Giamarellou, H.; Souli, M. Genomic characterization of a KPC-23-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clinical isolate resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 763.e5–763.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.; Karaiskos, I.; Karantani, I.; Papoutsaki, V.; Maraki, S.; Papaioannou, V.; Kazila, P.; Tsorlini, H.; Charalampaki, N.; Toutouza, M.; et al. Epidemiology and resistance phenotypes of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece, 2014 to 2016. Eur. Surveill. 2018, 23, 1700775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.; Nafplioti, K.; Adamou, P.; Karaiskos, I.; Giamarellou, H.; Souli, M. Correction to: Nationwide epidemiology of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Greek hospitals, with regards to plazomicin and aminoglycoside resistance. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.; Souli, M.; Nafplioti, K.; Adamou, P.; Karaiskos, I.; Giamarellou, H.; Antoniadou, A. In vitro activity of imipenem-relebactam against non-MBL carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in Greek hospitals in 2015–2016. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, M.; Chatzipanagiotou, S.; Hadjadj, L.; Petinaki, E.; Papagianni, S.; Charalampaki, N.; Tsiplakou, S.; Papaioannou, V.; Skarmoutsou, N.; Spiliopoulou, I.; et al. Inactivation of mgrB gene regulator and resistance to colistin is becoming endemic in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece: A nationwide study from 2014 to 2017. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatakis, T.; Zarras, C.; Pappa, S.; Vagdatli, E.; Iosifidis, E.; Roilides, E.; Papa, A. Emergence of ST39 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing VIM-1 and KPC-2. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 162, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopoulou, Κ.; Meletis, G.; Pappa, S.; Zotou, S.; Tsioka, K.; Dimitriadou, P.; Antoniadou, E.; Papa, A. Spread of NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary Greek hospital. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2021, 68, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malli, E.; Florou, Z.; Tsilipounidaki, K.; Voulgaridi, I.; Stefos, A.; Xitsas, S.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Petinaki, E. Evaluation of rapid polymyxin NP test to detect colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in a tertiary Greek hospital. J. Microbiol. Methods 2018, 153, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolitsis, I.; Feretzakis, G.; Katsimperis, S.; Angelopoulos, P.; Loupelis, E.; Skarmoutsou, N.; Tzelves, L.; Skolarikos, A. A 2-Year Audit on Antibiotic Resistance Patterns from a Urology Department in Greece. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Magkafouraki, E.; Moraitis, P.; Stafylaki, D.; Kasimati, A.; Scoulica, E. Epidemiology and in vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem-vaborbactam, imipenem-relebactam, eravacycline, plazomicin, and comparators against Greek carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Infection 2022, 50, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Stafylaki, D.; Scoulica, E. In vitro activity of newer β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, cefiderocol, plazomicin and comparators against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J. Chemother. 2023, 35, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroidi, A.; Katsiari, M.; Likousi, S.; Palla, E.; Roussou, Z.; Nikolaou, C.; Mathas, C.; Merkouri, E.; Platsouka, E.D. Changing Characteristics and In Vitro Susceptibility to Ceftazidime/Avibactam of Bloodstream Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from a Greek Intensive Care Unit. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M.; Bartzavali, C.; Karachalias, E.; Spiliopoulou, A.; Tsiata, E.; Siakallis, G.; Assimakopoulos, S.F.; Kolonitsiou, F.; Marangos, M. A Seven-Year Microbiological and Molecular Study of Bacteremias Due to Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Changes in the Carbapenemase Gene’s Distribution after Introduction of Ceftazidime/Avibactam. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M.; Bartzavali, C.; Lambropoulou, A.; Solomou, A.; Tsiata, E.; Anastassiou, E.D.; Fligou, F.; Marangos, M.; Spiliopoulou, I.; Christofidou, M. Reversal of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae epidemiology from blaKPC- to blaVIM-harbouring isolates in a Greek ICU after introduction of ceftazidime/avibactam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2051–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polemis, M.; Mandilara, G.; Pappa, O.; Argyropoulou, A.; Perivolioti, E.; Koudoumnakis, N.; Pournaras, S.; Vasilakopoulou, A.; Vourli, S.; Katsifa, H.; et al. COVID-19 and Antimicrobial Resistance: Data from the Greek Electronic System for the Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance-WHONET-Greece (January 2018–March 2021). Life 2021, 11, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansarli, G.S.; Papaparaskevas, J.; Balaska, M.; Samarkos, M.; Pantazatou, A.; Markogiannakis, A.; Mantzourani, M.; Polonyfi, K.; Daikos, G.L. Colistin resistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream isolates: Evolution over 15 years and temporal association with colistin use by time series analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilipounidaki, K.; Athanasakopoulou, Z.; Müller, E.; Burgold-Voigt, S.; Florou, Z.; Braun, S.D.; Monecke, S.; Gatselis, N.K.; Zachou, K.; Stefos, A.; et al. Plethora of Resistance Genes in Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria in Greece: No End to a Continuous Genetic Evolution. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilipounidaki, K.; Florou, Z.; Skoulakis, A.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Miriagou, V.; Petinaki, E. Diversity of Bacterial Clones and Plasmids of NDM-1 Producing Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates in Central Greece. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilipounidaki, K.; Gkountinoudis, C.-G.; Florou, Z.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Miriagou, V.; Petinaki, E. First Detection and Molecular Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa blaNDM-1 ST308 in Greece. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolaki, V.; Mantzarlis, K.; Mpakalis, A.; Malli, E.; Tsimpoukas, F.; Tsirogianni, A.; Papagiannitsis, C.; Zygoulis, P.; Papadonta, M.E.; Petinaki, E.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam To Treat Life-Threatening Infections by Carbapenem-Resistant Pathogens in Critically Ill Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02320-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarras, C.; Pappa, S.; Zarras, K.; Karampatakis, T.; Vagdatli, E.; Mouloudi, E.; Iosifidis, E.; Roilides, E.; Papa, A. Changes in molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the intensive care units of a Greek hospital, 2018–2021. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2022, 69, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbune, M.; Decusară, M.; Macovei, L.; Romila, A.; Iancu, A.; Indrei, L.; Pavel, L.; Raftu, G. Surveillance of Antibiotic Resistance Among Enterobacteriaceae Strains Isolated in an Infectious Diseases Hospital from Romania. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbune, M.; Gurau, G.; Niculet, E.; Iancu, A.V.; Lupasteanu, G.; Fotea, S.; Vasile, M.C.; Tatu, A.L. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance of ESKAPE Pathogens Over Five Years in an Infectious Diseases Hospital from South-East of Romania. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicus, A.; Lixandru, B.; Cîrstoiu, M.-M.; Usein, C.-R.; Cirstoiu, C. Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in an emergency university hospital. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 23, 13525–13529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, A.; Tarco, E.; Butiuc-Keul, A. Antibiotic resistance profiling of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae from Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Germs 2019, 9, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Főldes, A.; Bilca, D.-V.; Székely, E. Phenotypic and molecular identification of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae-challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Rev. Romana Med. Lab. 2018, 26, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Főldes, A.; Oprea, M.; Székely, E.; Usein, C.R.; Dobreanu, M. Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from Two Romanian Hospitals Co-Presenting Resistance and Heteroresistance to Colistin. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenea, A.E.; Zlatian, O.M.; Cristea, O.M.; Ungureanu, A.; Mititelu, R.R.; Balasoiu, A.T.; Vasile, C.M.; Salan, A.I.; Iliuta, D.; Popescu, M.; et al. TEM,CTX-M,SHV Genes in ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Clinical Samples in a County Clinical Emergency Hospital Romania-Predominance of CTX-M-15. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golli, A.L.; Cristea, O.M.; Zlatian, O.; Glodeanu, A.D.; Balasoiu, A.T.; Ionescu, M.; Popa, S. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens Causing Bloodstream Infections in an Intensive Care Unit. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 5981–5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manciuc, C. Resistance Profile of Multidrug-Resistant Urinary Tract Infections and Their Susceptibility to Carbapenems. Farmacia 2020, 68, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftode, I.L.; Leca, D.; Miftode, R.S.; Roşu, F.; Plesca, C.; Loghin, I.; Timpau, A.S.; Mitu, I.; Mititiuc, I.; Dorneanu, O.; et al. The Clash of the Titans: COVID-19, Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales, and First mcr-1-Mediated Colistin Resistance in Humans in Romania. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, S.; Flonta, M.M.M.; Almaş, A.; Buzea, M.; Licker, M.; Rus, M.; Földes, A.; Székely, E. Dissemination of NDM-1 carbapenemase-producer Providencia stuartii strains in Romanian hospitals: A multicentre study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompa, M.; Iancu, M.; Pandrea, S.L.; Grigorescu, M.; Ciontea, M.; Tompa, R.; Pandrea, S.; Junie, L. Carbapenem resistance determinants in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated from blood cultures-comparative analysis of molecular and phenotypic methods. Rev. Romana Med. Lab. 2022, 30, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coșeriu, R.L.; Mare, A.D.; Toma, F.; Vintilă, C.; Ciurea, C.N.; Togănel, R.O.; Cighir, A.; Simion, A.; Man, A. Uncovering the Resistance Mechanisms in Extended-Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates: Insights from Gene Expression and Phenotypic Tests. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, D.; Horhat, F.G.; Bădițoiu, L.; Dumitrașcu, V.; Bagiu, I.C.; Horhat, D.I.; Coșniță, D.A.; Krasta, A.; Dugăeşescu, D.; Licker, M. Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli: A Retrospective Study of Trends in a Tertiary Healthcare Unit. Medicina 2018, 54, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baditoiu, L.; Axente, C.; Lungeanu, D.; Muntean, D.; Horhat, F.; Moldovan, R.; Hogea, E.; Bedreag, O.; Sandesc, D.; Licker, M. Intensive care antibiotic consumption and resistance patterns: A cross-correlation analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2017, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftode, I.-L.; Pasare, M.-A.; Miftode, R.-S.; Nastase, E.; Plesca, C.E.; Lunca, C.; Miftode, E.-G.; Timpau, A.-S.; Iancu, L.S.; Dorneanu, O.S. What Doesn’t Kill Them Makes Them Stronger: The Impact of the Resistance Patterns of Urinary Enterobacterales Isolates in Patients from a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Europe. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandić-Pavlović, D.; Zah-Bogović, T.; Žižek, M.; Bielen, L.; Bratić, V.; Hrabač, P.; Slačanac, D.; Mihaljević, S.; Bedenić, B. Gram-negative bacteria as causative agents of ventilator-associated pneumonia and their respective resistance mechanisms. J. Chemother. 2020, 32, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Likić, S.; Žižek, M.; Bratić, V.; D’Onofrio, V.; Cavrić, G.; Pavliša, G.; Vodanović, M.; Gyssens, I.; Barišić, I. Causative agents of bloodstream infections in two Croatian hospitals and their resistance mechanisms. J. Chemother. 2023, 35, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Luxner, J.; Car, H.; Sardelić, S.; Bogdan, M.; Varda-Brkić, D.; Šuto, S.; Grisold, A.; Beader, N.; Zarfel, G. Emergence and Spread of Enterobacterales with Multiple Carbapenemases after COVID-19 Pandemic. Pathogens 2023, 12, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Pešorda, L.; Krilanović, M.; Beader, N.; Veir, Z.; Schoenthaler, S.; Bandić-Pavlović, D.; Frančula-Zaninović, S.; Barišić, I. Evolution of Beta-Lactamases in Urinary Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from Croatia; from Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases to Carbapenemases and Colistin Resistance. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Sardelić, S.; Bogdanić, M.; Zarfel, G.; Beader, N.; Šuto, S.; Krilanović, M.; Vraneš, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) in urinary infection isolates. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, L.; Likić, R.; Erdeljić, V.; Mareković, I.; Firis, N.; Grgić-Medić, M.; Godan, A.; Tomić, I.; Hunjak, B.; Markotić, A.; et al. Activity of fosfomycin against nosocomial multiresistant bacterial pathogens from Croatia: A multicentric study. Croat. Med. J. 2018, 59, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, V.; Conzemius, R.; Varda-Brkić, D.; Bogdan, M.; Grisold, A.; Gyssens, I.C.; Bedenić, B.; Barišić, I. Epidemiology of colistin-resistant, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii in Croatia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 81, 104263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelić, M.; Škrlin, J.; Bejuk, D.; Košćak, I.; Butić, I.; Gužvinec, M.; Tambić-Andrašević, A. Characterization of Isolates Associated with Emergence of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Croatia. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, I.; Bošnjak, Z.; Ćorić, M.; Lešin, J.; Mareković, I. In vitro susceptibility of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales to eravacycline—The first report from Croatia. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić Paradžik, M.; Drenjančević, D.; Presečki-Stanko, A.; Kopić, J.; Talapko, J.; Zarfel, G.; Bedenić, B. Hidden Carbapenem Resistance in OXA-48 and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Positive Escherichia coli. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Bratić, V.; Mihaljević, S.; Lukić, A.; Vidović, K.; Reiner, K.; Schöenthaler, S.; Barišić, I.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in a COVID-19 Hospital in Zagreb. Pathogens 2023, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćirković, I.; Marković-Denić, L.; Bajčetić, M.; Dragovac, G.; Đorđević, Z.; Mioljević, V.; Urošević, D.; Nikolić, V.; Despotović, A.; Krtinić, G.; et al. Microbiology of Healthcare-Associated Infections: Results of a Fourth National Point Prevalence Survey in Serbia. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, Z.; Folic, M.; Gajović, N.; Jankovic, S. Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Hospital Infection in the Intensive Care Unit. Serbian J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 19, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, Z.M.; Folic, M.M.; Jankovic, S.M. Previous Antibiotic Exposure and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Patients with Nosocomial Infections. Balk. Med. J. 2017, 34, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric, O.; Markovic-Denic, L.; Jovanovic, B.; Bumbasirevic, V. High incidence of multiresistant bacterial isolates from bloodstream infections in trauma emergency department and intensive care unit in Serbia. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2019, 66, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folic, M.M.; Djordjevic, Z.; Folic, N.; Radojevic, M.Z.; Jankovic, S.M. Epidemiology and risk factors for healthcare-associated infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Chemother. 2021, 33, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabic, J.; Fortunato, G.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Kekic, D.; Jovicevic, M.; Pesovic, J.; Ranin, L.; Opavski, N.; Manaia, C.M.; Gajic, I. Dissemination of Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Serbian Hospital Settings: Expansion of ST235 and ST654 Clones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković, M.; Nenadović, Ž.; Stanković, S.; Božić, D.D.; Nedeljković, N.S.; Ćirković, I.; Petrović, M.; Dimkić, I. Phenotypic and genetic properties of susceptible and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Southern Serbia. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2020, 71, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Pelegrin, A.C.; Mirande, C.; Brkic, S.; Cirkovic, I.; Goossens, H.; Rossolini, G.M.; van Belkum, A. Genomic Epidemiology of Carbapenem- and Colistin-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates From Serbia: Predominance of ST101 Strains Carrying a Novel OXA-48 Plasmid. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornic, S.; Petrovic, I.; Lukovic, B. In vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam and ceftazidime/avibactam against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from blood cultures in a University hospital in Serbia. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2023, 70, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobreva, E.; Ivanov, I.; Donchev, D.; Ivanova, K.; Hristova, R.; Dobrinov, V.; Sabtcheva, S.; Kantardjiev, T. In vitro Investigation of Antibiotic Combinations against Multi- and Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyanev, T.; Nguyen, M.N.; Markovska, R.; Stankova, P.; Xavier, B.B.; Lammens, C.; Marteva-Proevska, Y.; Velinov, T.; Cantón, R.; Goossens, H.; et al. Emergence of ST654 Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-harbouring bla(NDM-1) and bla(GES-5) in novel class I integron In1884 from Bulgaria. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 672–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovska, R.; Stoeva, T.; Boyanova, L.; Stankova, P.; Schneider, I.; Keuleyan, E.; Mihova, K.; Murdjeva, M.; Sredkova, M.; Lesseva, M.; et al. Multicentre investigation of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in Bulgarian hospitals—Interregional spread of ST11 NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 69, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, A.; Feodorova, Y.; Miteva-Katrandzhieva, T.; Petrov, M.; Murdjeva, M. First detected OXA-50 carbapenem-resistant clinical isolates Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Bulgaria and interplay between the expression of main efflux pumps, OprD and intrinsic AmpC. J. Med. Microbiol. 2019, 68, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, A.P.; Stanimirova, I.D.; Ivanov, I.N.; Petrov, M.M.; Miteva-Katrandzhieva, T.M.; Grivnev, V.I.; Kardjeva, V.S.; Kantardzhiev, T.V.; Murdjeva, M.A. Carbapenemase Production of Clinical Isolates Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a Bulgarian University Hospital. Folia Med. (Plovdiv.) 2017, 59, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Savov, E.; Politi, L.; Spanakis, N.; Trifonova, A.; Kioseva, E.; Tsakris, A. NDM-1 Hazard in the Balkan States: Evidence of the First Outbreak of NDM-1-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Bulgaria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, D.; Niyazi, D.; Bozhkova, M.; Stoeva, T. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from patients in COVID-19 wards and ICUs in a Bulgarian University Hospital. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2023, 70, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudejova, K.; Kraftova, L.; Mattioni Marchetti, V.; Hrabak, J.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Bitar, I. Genetic Plurality of OXA/NDM-Encoding Features Characterized from Enterobacterales Recovered From Czech Hospitals. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 641415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, R.; Chudejova, K.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Medvecky, M.; Habalova, K.; Hobzova, L.; Bolehovska, R.; Pliskova, L.; Hrabak, J.; Zemlickova, H. Characterization of KPC-Encoding Plasmids from Enterobacteriaceae Isolated in a Czech Hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Medvecky, M.; Chudejova, K.; Skalova, A.; Rotova, V.; Spanelova, P.; Jakubu, V.; Zemlickova, H.; Hrabak, J. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa of Czech Origin and Evidence for Clonal Spread of Extensively Resistant Sequence Type 357 Expressing IMP-7 Metallo-β-Lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskova, V.; Medvecky, M.; Skalova, A.; Chudejova, K.; Bitar, I.; Jakubu, V.; Bergerova, T.; Zemlickova, H.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Hrabak, J. Characterization of NDM-Encoding Plasmids from Enterobacteriaceae Recovered from Czech Hospitals. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdács, M. Carbapenem-Resistant but Cephalosporin-Susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Urinary Tract Infections: Opportunity for Colistin Sparing. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdács, M.; Ábrók, M.; Lázár, A.; Jánvári, L.; Tóth, Á.; Terhes, G.; Burián, K. Detection of VIM, NDM and OXA-48 producing carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales among clinical isolates in Southern Hungary. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2020, 67, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neall, D.; Juhász, E.; Tóth, Á.; Urbán, E.; Szabó, J.; Melegh, S.; Katona, K.; Kristóf, K. Ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam susceptibility of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains in Hungary. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2020, 67, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalali, Y.; Sturdik, I.; Jalali, M.; Payer, J. Isolated carbapenem resistant bacteria, their multidrug resistant profile, percentage of healthcare associated infection and associated mortality, in hospitalized patients in a University Hospital in Bratislava. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2021, 122, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagaletsios, L.A.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Petinaki, E. Prevalence and analysis of CRISPR/Cas systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Greece. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. In WHO/Newsroom/Spotlight; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Health Union: Identifying Top 3 Priority Health Threats; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-07/hera_factsheet_health-threat_mcm.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Coppry, M.; Jeanne-Leroyer, C.; Noize, P.; Dumartin, C.; Boyer, A.; Bertrand, X.; Dubois, V.; Rogues, A.-M. Antibiotics associated with acquisition of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ICUs: A multicentre nested case–case–control study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerther, P.-L.; Lepeule, R.; Burdet, C.; Decousser, J.-W.; Ruppé, É.; Barbier, F. Carbapenems and alternative β-lactams for the treatment of infections due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: What impact on intestinal colonisation resistance? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versporten, A.; Zarb, P.; Caniaux, I.; Gros, M.-F.; Drapier, N.; Miller, M.; Jarlier, V.; Nathwani, D.; Goossens, H.; Koraqi, A. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: Results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e619–e629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe, 2022 Data: Executive Summary; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, Y. Treatment Options for Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S565–S575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, M.; Hall, D.; Stoneburner, A.; Shinabarger, D.; Serio, A.W.; Krause, K.M.; Marra, A.; Pillar, C. Activity of plazomicin in combination with other antibiotics against multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 92, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Xue, F.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, B. Synergism of eravacycline combined with other antimicrobial agents against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 30, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KS, S.; Pallam, G.; Mandal, J.; Jindal, B. Use of fosfomycin combination therapy to treat multidrug-resistant urinary tract infection among paediatric surgical patients—A tertiary care centre experience. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, acmi000163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O.J.; Huttner, B.; Schouten, J.; Pulcini, C. What is antimicrobial stewardship? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Bamberg, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Maloney, M.; McAllister-Hollod, L.; Nadle, J.; et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellit, T.H.; Owens, R.C.; McGowan, J.E., Jr.; Gerding, D.N.; Weinstein, R.A.; Burke, J.P.; Huskins, W.C.; Paterson, D.L.; Fishman, N.O.; Carpenter, C.F.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | No. of Isolates | CR Rate n (%) | Prevalence of KPC Mechanism a (n/N, %) | Prevalence of MBL Mechanism a (n/N, %) | Prevalence of OXA-48 Mechanism a (n/N, %) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 188 | 188 (100) | 85/162 (52.5) | NDM: 87/188 (46.3) VIM: 16/150 (10.7) | OXA-48: 3/150 (2) | [106,111] |

| Croatia | 588 | 583 (99.2) | 57/474 (12.0) | VIM: 149/504 (26.6) NDM: 26/428 (6.1) | OXA-48: 83/474 (17.5) | [86,87,88,90,91,92,93,94,96] |

| Czechia | 33 | 33 (100) | 10/33 (30.3) | NDM: 23/33 (69.7) | OXA-48: 4/11 (36.4) | [113,114,116] |

| Greece | 7257 | 4819 (66.4) | 2328/3872 (60.1) | NDM: 417/3469 (12) VIM: 317/3440 (9.2) | OXA-48: 154/3872 (4.0) | [46,47,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Hungary | 1474 | 27 (1.8) | - | VIM: 21/27 (77.8) NDM: 2/27 (7.4) | OXA-48: 6/27 (22.2) | [18,118] |

| Poland | 6968 | 3324 (47.7) | 202/743 (27.2) | NDM: 2263/2986 (75.8) VIM: 137/850 (16.1) | OXA-48: 359/743 (48.3) | [20,21,22,23,24,25,27,29,30,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,45] |

| Romania | 3396 | 790 (23.2) | 24/220 (10.9) | NDM: 103/268 (38.4) VIM: 7/112 (6.3) | OXA-48: 96/220 (43.6) | [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,85] |

| Serbia | 2724 | 703 (25.8) | 24/188 (12.8) | NDM: 14/188 (7.4) | OXA-48: 123/188 (65.4) | [97,98,100,105] |

| Slovakia | 14 | 100 (100) | ND | ND | ND | [120] |

| Country | Pathogen | No. of CR Strains | IMI/REL Resistance (%) | CAZ/AVI Resistance (%) | Resistance Mechanisms (%) a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croatia | Enterobacterales | 10 | 100 | 50 | OXA-48: 100 NDM: 50 KPC: 20 VIM: 10 | [88] |

| Greece | K. pneumoniae | 314 | 7.3 | 0.3 | KPC: 94 OXA-48: 6 | [52] |

| Greece | K. pneumoniae | 266 | 24 | 20.3 | KPC: 75.6 NDM: 11.7 VIM: 5.6 OXA-48: 4.1 | [58] |

| Greece | K. pneumoniae | 110 | 34.5 | 33.7 | KPC: 64.6 NDM: 20.9 VIM: 8.2 OXA-48: 2.7 | [59] |

| Greece | Enterobacterales | 422 | 39.8 | 40.2 | KPC: 57.3 MBL: 44 OXA-48: 8.8 | [47] |

| Poland | Klebsiella spp. | 106 | 82.6 | 82.6 | VIM: 100 | [22] |

| Romania | K. pneumoniae | 10 | 50 | 20 | OXA-48: 40 KPC: 40 NDM: 20 | [75] |

| Serbia | K. pneumoniae | 143 | 51.8 | 25.9 | OXA-48: 60 NDM: 8.2 KPC: 16.5 | [105] |

| Country | No. of Isolates | CR Rate, n (%) | MBL Mechanism Prevalence a, n/N (%) | Other Mechanisms a, n/N (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 80 | 74 (92.5) | NDM: 5/5 (100) | OXA-50: 3/32 (9.3) | [107,109,110] |

| Croatia | 70 | 54 (77.1) | VIM: 8/8 (100) | GES: 5/5 (100) | [86,87,91] |

| Czechia | 289 | 167 (57.9) | VIM: 15/138 (10.9) IMP: 119/138 (86.2) | GES: 4/138 (2.9) | [115] |

| Greece | 1179 | 376 (31.9) | VIM: 13/39 (33.3) NDM: 9/39 (23.1) | ND | [57,65,67,121] |

| Hungary | 2284 | 436 (19.1) | VIM: 64/77 (83.1) NDM: 7/65 (10.8) | ND | [18,117,119] |

| Poland | 1555 | 805 (51.8) | MBL: 486/489 (99.4) | ND | [23,24,26,40,42,43,44,45] |

| Romania | 386 | 179 (46.4) | ND | ND | [71,77] |

| Serbia | 1111 | 593 (53.4) | NDM: 31/138 (22.5) | ND | [100,101,102] |

| Slovakia | 16 | 16 (100) | ND | ND | [120] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piotrowski, M.; Alekseeva, I.; Arnet, U.; Yücel, E. Insights into the Rising Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Epidemic Infections in Eastern Europe: A Systematic Literature Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13100978

Piotrowski M, Alekseeva I, Arnet U, Yücel E. Insights into the Rising Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Epidemic Infections in Eastern Europe: A Systematic Literature Review. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(10):978. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13100978

Chicago/Turabian StylePiotrowski, Michal, Irina Alekseeva, Urs Arnet, and Emre Yücel. 2024. "Insights into the Rising Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Epidemic Infections in Eastern Europe: A Systematic Literature Review" Antibiotics 13, no. 10: 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13100978

APA StylePiotrowski, M., Alekseeva, I., Arnet, U., & Yücel, E. (2024). Insights into the Rising Threat of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Epidemic Infections in Eastern Europe: A Systematic Literature Review. Antibiotics, 13(10), 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13100978