Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participants

2.2. Co-Design Sessions and Interview Findings

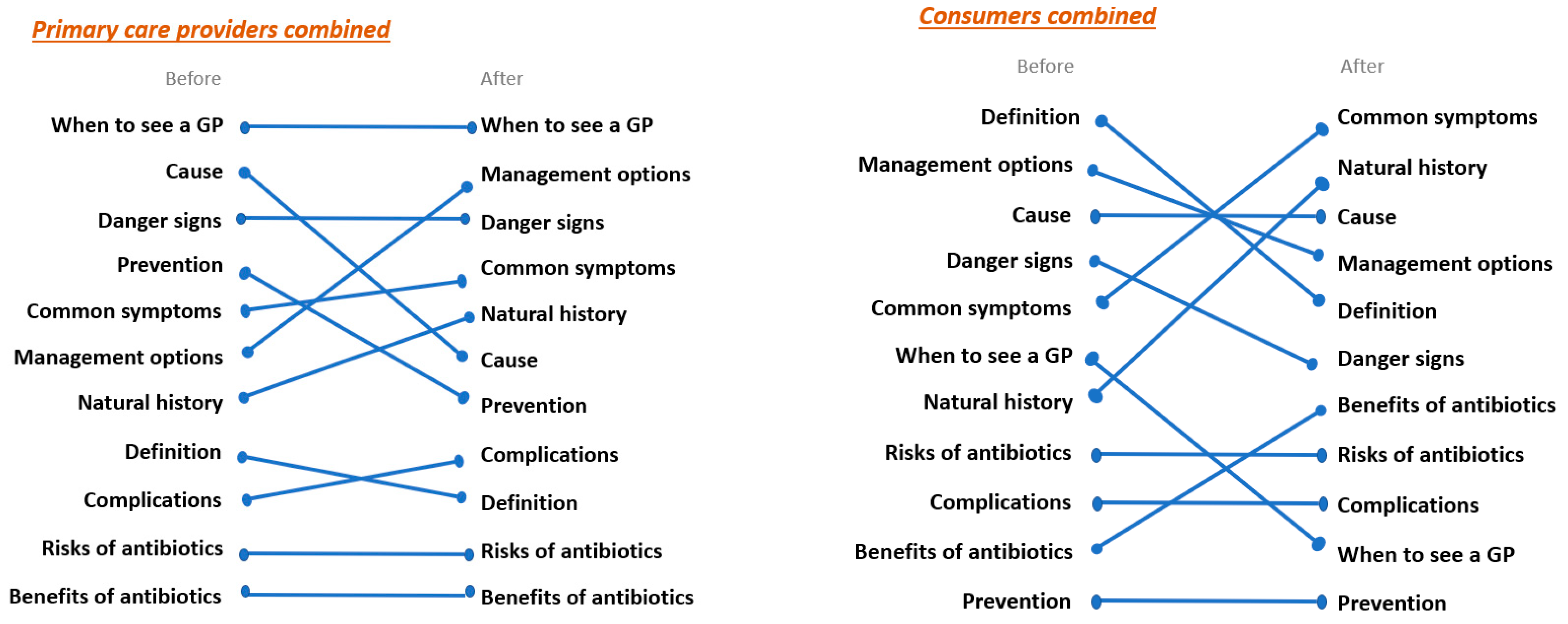

2.2.1. Content

“We want the important stuff on the first page, and I think this stuff on the first page that’s irrelevant and meaningless should be on the back page and vice versa.”Participant 11, consumer, co-design session 1.

“… the message it’s trying to convey, it’s a very simplified version of them writing it out and having lots of words and stats and things like that, so they’ve done it in a good way …”Participant 5, pharmacist, co-design session 1.

“… and you don’t need the words ‘suprapubic pain’ … you just need to say if you’ve got blood in your urine or feel the need to pass urgently. I don’t think you need actual medical terms …”Participant 2, GP, co-design session 1.

“… it’s easy to read, and it draws your attention to it with the pictures on the side, the decorations on the side, and it’s got the headings in bold, and short description. I think this is good for the public consumers.”Participant 8, consumer, co-design session 1.

“If your symptoms aren’t improving, if you’re not getting better, and I think that’s why I personally prioritised that higher, because, that’s … if people aren’t getting better, not improving, to come back and see me.”Participant 1, GP, co-design session 2.

“With the benefits and risks, I just think it is a bit too complex to be on the person’s level of health literacy.”Participant 5, pharmacist, co-design session 1.

2.2.2. Communication of Content

“I’ve had a patient who took their two Panadol, and they had their Panamax, and they had their paracetamol.”Participant 4, practice nurse, co-design session 2.

2.2.3. Design

“There’s nothing highlighted, there’s nothing to stand out, it’s all put with the same importance as everything else so—there’s no highlight of the fact when to see a doctor, it’s exactly the same text as symptoms.”Participant 10, consumer, co-design session 1 (reviewing existing patient information sheets).

“I love the way you’ve bolded some of the things because I always either highlight or underline, I’m like, “These are the reasons I want you to come see me.”. So the fact that that’s already done would be good. I wouldn’t have to go searching for my highlighter …”Participant 1, GP, co-design session 2 (reviewing Shared Decision Support Patient Information Sheet Bronchitis prototype).

“If it is going to be a two-pager, you’re not going to get them to turn over to read the second page.”Participant 5, pharmacist, co-design session 1.

“If you’re going to get someone to do something, it needs to be really short.”Participant 1, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

2.2.4. Delivery and Access

“I was thinking—this is before they see the doctor. This might be at the chemist’s, or it could be online or in a childcare centre or a school, or I don’t know, whatever—a community thing where people see information.”Participant 2, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

“We could put it on the practice website, you know, in our resources section”Participant 1, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

“I think this is really good … when I go and see him (GP) and quite often … he pulls up an information sheet, and he clicks ‘print’. Then he prints it and hands it to me as here’s some more information. So it would be nice if he has this in a file and can just hand it to me. Because when he actually hands it to me, hands me this information, I actually read it.”Participant 9, consumer, co-design session 2.

“I also think quite a few, especially elderly patients, don’t use computers and emails. So I think for them, you need to have a written handout that their doctor gives them.”Participant 8, consumer, co-design session 1.

2.2.5. Usability

“I use the three-click rule when we talk about all this co-design stuff. If they’re too far away … GPs won’t use it.”Participant 3, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

“Half the time—normally, I can make up my mind pretty quickly about what needs to happen … The hard part, then, is the … communication. It’s educating. If I’ve got a tool or resource, which is easily accessible—I know where it is, it sits on my screen, I can print it off, it saves me so much time.”Participant 1, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

“… I see so many people … who come in with symptoms suggestive of a viral sinusitis and often want to have that discussion about getting antibiotics. I think that the way the … tool is written and formatted would make it really … user-friendly and great to have it in a consult …”Participant 1, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

2.2.6. Engagement

“[The tools] takes it away from the doctor and says, ‘What brings you here today?’, ‘That cough’s back again, I need the antibiotics.’ ‘Okay, let’s talk about that. There’s this new tool that I have …’”.Participant 3, GP, co-design session 1.

“It’s another resource, then they’re going to walk away with … a piece of paper that says I’m not taking antibiotics, but I’m going to have some rest, sleep, drink more fluids”.Participant 5, pharmacist, co-design session 1.

“I think if I could give them this sheet with that and say, ‘Look, this is what the advice is saying. You don’t need antibiotics, you need to go home and take some Panadol and rest …”.Participant 1, GP, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

“I think if I have an ailment of some sort and I want to quickly decide before I contact a doctor what the best initial course of action is, I think these would be quite useful.”.Participant 10, consumer, Session 3—Participant Interviews.

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Participant Recruitment

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4.3.1. Co-Design Session 1

4.3.2. Co-Design Session 2

4.3.3. Session 3/Participant Interviews

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jonas, O.B.; Irwin, A.; Berthe, F.C.J.; Le Gall, F.G.; Marquez, P.V. Drug-Resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future (Vol. 2): Final Report (English). HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative Washington, D.C. World Bank Group. 2017. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/final-report (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. In Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; HM Government and Wellcome Trust: London, UK, 2016.

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. AURA 2016: First Australian Report on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Human Health. 2016. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/AURA-2016-First-Australian-Report-on-Antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-in-human-health.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Moro, M.L.; Marchi, M.; Gagliotti, C.; Mario, S.D.; Resi, D.; “Progetto Bambini a Antibiotici [ProBA]” Regional Group. Why do paediatricians prescribe antibiotics? Results of an Italian regional project. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whaley, L.E.; Businger, A.C.; Dempsey, P.D.; Linder, J.A. Visit coplexity, diagnostic uncertainty, and antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in primary care: A retrospective study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, C.R.; Gonzales, R.; Camargo, J.C.A.; Maselli, J.; Metlay, J.P. Antibiotic Prescriptions Are Associated with Increased Patient Satisfaction With Emergency Department Visits for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, M.; White, P.; Jongsma, H.; Schofield, P.; Armstrong, D. Antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction in primary care in England: Cross-sectional analysis of national patient survey data and prescribing data. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e40–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biezen, R.; Brijnath, B.; Grando, D.; Mazza, D. Management of respiratory tract infections in young children—A qualitative study of primary care providers’ perspectives. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2017, 27, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, P.P.; Businger, A.C.; Whaley, L.E.; Gagne, J.J.; Linder, J.A. Primary care clinicians’ perceptions about antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis: A qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.; Nakase, J.; Moran, G.J.; Karras, D.J.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Talan, D.A. Antibiotic use for emergency department patients with upper respiratory infections: Prescribing practices, patient expections, and patient satisfaction. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007, 50, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagger, K.; Nielsen, A.B.S.; Siersma, V.; Bjerrum, L. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and demand for antibiotics in patients with upper respiratory tract infections is hardly different in female versus male patients as seen in primary care. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 21, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. AURA 2019: Third Australian Report on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Human Health. 2019. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/AURA-2019-Report.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Bae, J.-M. Shared decision making: Relevant concepts and facilitating strategies. Epidemiol. Health 2017, 39, e2017048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, M.B.; Elmes, A.; McKenzie, J.E.; Trevena, L.; Hetrick, S.E. Right choice, right time: Evaluation of an online decision aid for youth depression. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.B. Patient decision aids to engage adults in treatment or screening decisions. JAMA 2017, 318, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, S.T.; Newman, L.; Griggs, J.J.; Kosir, M.A.; Katz, S.J. Evaluating a Decision Aid for Improving Decision Making in Patients with Early-stage Breast Cancer. Patient 2016, 9, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, P.Y.; Ng, C.J.; Teo, C.H.; Abu Bakar, A.I.; Abdullah, K.L.; Khoo, E.M.; Hanafi, N.S.; Low, W.Y.; Chiew, T.K. Usability and utility evaluation of the web-based “Should I Start Insulin?” patient decision aid for patients with type 2 diabetes among older people. Inform. Health Soc. Care. 2018, 43, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coxeter, P.D.; Del Mar, C.; Hoffmann, T. Preparing Parents to Make An Informed Choice About Antibiotic Use for Common Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: A Randomised Trial of Brief Decision Aids in a Hypothetical Scenario. Patient 2017, 10, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avent, M.L.; Hansen, M.P.; Gilks, C.; Del Mar, C.; Halton, K.; Sidjabat, H.; Hall, L.; Dobson, A.; Paterson, D.L.; van Driel, M. General Practitioner Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme Study (GAPS): Protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, V.M.; LeBlanc, A.; Buchholz, A.; Stilwell, D.L.; Tsapas, A. Basing information on comprehensive, critically appraised, and up-to-date syntheses of the scientific evidence: A quality dimension of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargraves, I.; Montori, V.M. Decision aids, empowerment, and shared decision making. BMJ 2014, 349, g5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient Decision Aids 2019. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/shared-decision-making/patient-decision-aids/ (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, C. Applying Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Physicians’ Shared Decision-Making With Patients With Acute Respiratory Infections in Primary Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 785419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mar, C.; Hoffmann, T.; Bakhit, M. How can general practitioners reduce antibiotic prescribing in collaboration with their patients? Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 51, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, C.J.W.; Fulleborn, S.T.; Jackson, J.T.; Rogers, T.; Samar, H. Dissonance in the discourse of the duration of diabetes: A mixed methods study of patient perceptions and clinical practice. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K.; Le Roux, E.; Banks, J.; Ridd, M.J. GP and parent dissonance about the assessment and treatment of childhood eczema in primary care: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biezen, R.; Grando, D.; Mazza, D.; Brijnath, B. Dissonant views—GPs’ and parents’ perspectives on antibiotic prescribing for young children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stivers, T.; Mangione-Smith, R.; Elliott, M.N.; McDonald, L.; Heritage, J. Why do physicians think parents expect antibiotics? What parents report vs what physicians believe. J. Fam. Pract. 2003, 52, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shlomo, V.; Adi, R.; Eliezer, K. The knowledge and expectations of parents about the role of antibiotic treatment in upper respiratory tract infection—A survey among parents attending the primary physician with their sick child. BMC Fam. Pract. 2003, 4, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Canet-Fajas, C.; Delgado-Marroquín, M.T.; Magallón-Botaya, R.; Romero-Martín, M.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in Primary Health Care: A systematic review. Medicine 2020, 99, e21389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhit, M.; Del Mar, C.; Gibson, E.; Hoffmann, T. Shared decision making and antibiotic benefit-harm conversations: An observational study of consultations between general practitioners and patients with acute respiratory infections. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Melbourne. Data for Decisions and the Patron Program of Research—Creating Knowledge from Primary Care Data through Research. 2022. Available online: https://medicine.unimelb.edu.au/school-structure/general-practice/engagement/data-for-decisions (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Therapeutic Guidelines Limited. Therapeutic Guidelines. 2018. Available online: https://www.tg.org.au/ (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Manski-Nankervis, J.; Biezen, R.; James, R.; Thursky, K.; Buising, K. A need for action: Results from the Australian General Practice National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (GP NAPS). In Proceedings of the Society for Academic Primary Care, London, UK, 10–12 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Primary Care Providers | Gender | Age (Years) | Years of Experience (Primary Care) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 (GP) | Female | 26–35 | 2 |

| Participant 2 (GP) | Male | 46–55 | 27 |

| Participant 3 (GP) | Female | 56–65 | 30 |

| Participant 4 (Practice Nurse) | Female | 26–35 | 5 |

| Participant 5 (Pharmacist) | Female | 26–35 | 1 |

| Consumers | Gender | Age (Years) | Number of GP Visits per Year |

| Participant 6 | Male | 18–25 | 2 |

| Participant 7 | Male | >75 | 3 |

| Participant 8 | Female | 66–75 | 4 |

| Participant 9 | Male | 46–55 | 3 |

| Participant 10 | Female | 36–45 | 3 |

| Participant 11 | Male | 46–55 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biezen, R.; Ciavarella, S.; Manski-Nankervis, J.-A.; Monaghan, T.; Buising, K. Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030458

Biezen R, Ciavarella S, Manski-Nankervis J-A, Monaghan T, Buising K. Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(3):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030458

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiezen, Ruby, Stephen Ciavarella, Jo-Anne Manski-Nankervis, Tim Monaghan, and Kirsty Buising. 2023. "Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology" Antibiotics 12, no. 3: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030458

APA StyleBiezen, R., Ciavarella, S., Manski-Nankervis, J.-A., Monaghan, T., & Buising, K. (2023). Addressing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Primary Care—Developing Patient Information Sheets Using Co-Design Methodology. Antibiotics, 12(3), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030458