1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a considerable and growing threat to global health, food security, and development [

1,

2]. Overall, AMR is associated with increased morbidity and mortality as well as increased length of hospital stay and overall costs [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In 2019, an estimated 4.95 million deaths globally were associated with AMR, with the greatest burden in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia [

9]. If not addressed, gross domestic product (GDP) per country could be reduced by 3.8% by 2050 [

10].

The extensive and inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the leading causes of the development of AMR among disease-causing pathogens [

2,

11]. Irrational prescribing patterns, lack of standard diagnostic facilities, inappropriate awareness of AMR, insufficient infection control and preventive practices, and the lack of treatment guidelines are seen as prominent factors in the development of AMR [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Hospital settings, particularly in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), are highly vulnerable to AMR due to excessive use of antibiotics where at least 20–50% of antibiotic utilization is reported to be irrational [

2,

13,

16,

17].

Pakistan is a LMIC in South Asia with high AMR rates enhanced by high consumption of antimicrobials [

18,

19]. Studies indicate 91% of

E. coli, 91.7% of

S. Typhi, 90.9% of

Acinetobacter species, and 100% of

Klebsiella species were reported to be resistant to amikacin, fluoroquinolone, imipenem, and third generation cephalosporins, respectively [

20,

21,

22]. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) typhoid in 2016 in Sindh Provinces, Pakistan, also led to appreciable global health concerns [

23,

24].

Health care workers (HCWs), including pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, play a critical role in educating patients about the appropriate use of antibiotics in ambulatory care and hospitals across countries. Other activities include minimizing the spread of infection through education about hygiene and personal protection, as well as through administering vaccines [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In addition, they are directly involved in the prescribing, dispensing, administration, and monitoring of antibiotic use in the complex medication use process in hospital settings across countries [

17,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) are considered an important tool to address the ongoing threat of AMR [

2,

17,

35,

36,

37,

38]. This is because ASPs aim to optimize the prescribing of antimicrobials by promoting rational antibiotic use, thereby reducing health care costs associated with AMR and its impact [

2,

17,

39,

40]. However, there are currently concerns with the implementation of ASPs in Pakistan [

38].

Pakistan launched its national action plan (NAP) against AMR in 2017. Core objectives included the development and implementation of a national awareness strategy against AMR, the establishment of national surveillance of AMR and the enforcement of infection control and preventive practices [

40,

41]. In 2018, an assessment of ongoing activities stressed the need to establish a multisectoral approach to improve laboratory standards, enhance rational antibiotic use, as well as increase the awareness of antibiotics among HCWs and the general public [

42]. This built on identified challenges with implementing the NAP [

19].

We are aware that previous studies have been undertaken among HCWs in the different regions of Pakistan, including physicians and pharmacists as well as medical and pharmacy students, to ascertain key aspects regarding antibiotics use, AMR, and ASPs [

38,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. However, we are unaware of any studies that have been conducted to fully evaluate knowledge of antibiotic use, AMR, and ASPs among pharmacy technicians serving specifically in ambulatory care facilities. This is important since pharmacy technicians are involved in the procurement, storage, dispensing of prescriptions written by physicians, as well as the administration of medicines including antibiotics in health facilities treating both inpatients and ambulatory care patients. However, there have been studies assessing key factors associated with the inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics among non-pharmacy workers in Pakistan [

50].

Consequently, we sought to address this by conducting a cross-sectional survey among pharmacy technicians in ambulatory care facilities in the Punjab province of Pakistan to provide guidance on future potential activities where there are concerns. This is because pharmacy technicians can play an effective role in combating AMR by ensuring appropriate dispensing of antibiotics against a valid prescription, manage used antibiotics, promote AMR awareness, counselling patients to complete their antibiotic regime, and cooperating with other healthcare professionals [

51]. Moreover, pharmacy personnel can establish effective ASPs in ambulatory care settings [

51,

52,

53]. There are also high rates of antibiotic dispensing without a prescription in Pakistan despite current regulations [

54,

55]. This also needs to be addressed going forward.

3. Discussion

This study provided an in-depth understanding of pharmacy technicians’ knowledge regarding antibiotics and AMR in Pakistan. The findings showed that most pharmacy technicians had a reasonable understanding of antibiotics and their use, with approximately two thirds being aware that antibiotics are frequently prescribed, there can be allergies and patients should not discontinue antibiotics when symptoms are improving. These findings are similar to the previous study conducted in Pakistan among pharmacy students [

47]. However, of concern was a poor understanding regarding the preventive use of antibiotics for future infections, antibiotics can be effective for viral infections, left-over antibiotics can be re-used, and the availability of antibiotics without a prescription. These findings, though, are better than those in a study from India where less than a quarter of Bachelor of Pharmacy students knew about the use of antibiotics for common colds [

56].

Encouragingly, our study reported that excessive use of antibiotics, inappropriate dosages, and duration, as well as a lack of regulatory enforcement that permit easy availability of antibiotics, are common factors resulting in irrational use of antibiotics and, consequently, rising AMR rates in Pakistan. These findings are similar to the previous study in India where most paramedic staff knew that the overuse of antibiotics was a leading cause of AMR [

57]. However, most pharmacy technicians were unaware of terminology such as superbugs, multidrug resistant and extensive drug resistance infection, and the National Action Plan of Pakistan against AMR. This is a concern, similar to a study from Sri Lanka where most pharmacy students were unaware about terms such as superbugs [

58].

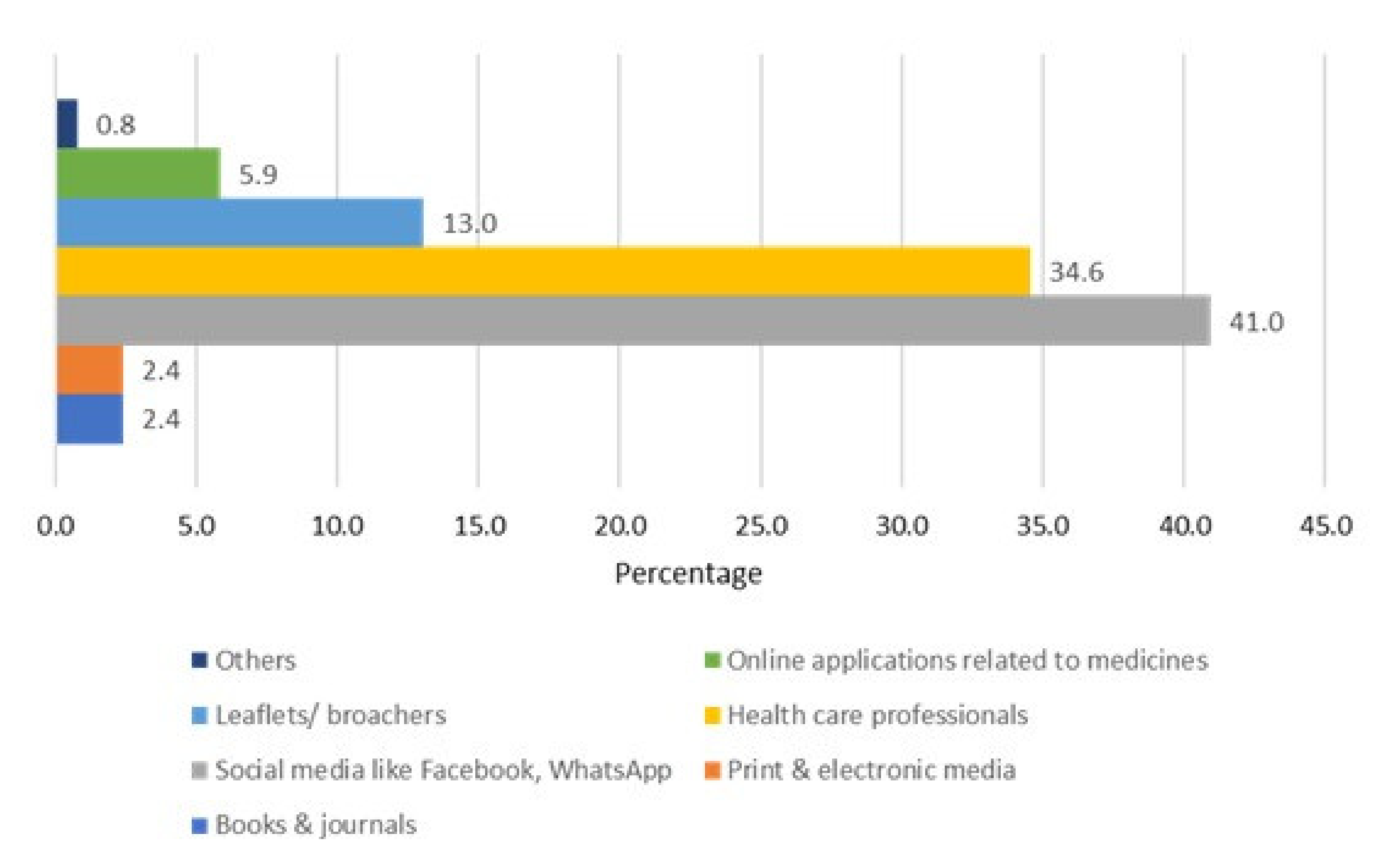

Our study also revealed that most pharmacy technicians were not aware of the core elements of ASPs, the purpose of ASP, and how ASPs enhance the appropriate utilized antimicrobial agents. The primary reasons for this could be the lack of these initiatives in Pakistan, specifically at these remote health facilities. The lack of knowledge in these areas was also related to status and experience, which needs to be factored in going forward. These findings though are similar to studies in other LMICs where health professionals, including pharmacists, had inadequate knowledge of antibiotics and ASPs [

59,

60,

61]. This again needs addressing going forward in Pakistan. Potential activities to address these concerns include instigating appropriate educational activities among pharmacy technicians during their diploma training and post qualification with the help of senior technicians and pharmacists in the various settings [

2,

62]. This is particularly important since social media, including Facebook and WhatsApp, were the most common sources of information for the surveyed pharmacy technicians rather than other healthcare professionals or any national guidelines which should be updated as part of national action plan activities [

19]. Any guidelines produced should be robust, easy to follow, and regularly updated to enhance their use and improve future antimicrobial prescribing [

63,

64]. Educational activities can also assist with addressing some of the misinformation that can arise from social media, which was particularly prevalent during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This included the widespread promotion of re-purposed treatments including hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and ivermectin despite limited evidence, all of which were subsequently shown to have limited benefit alongside harm in some patients [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71].

We are aware of a number of limitations with our study. Firstly, we collected data only from seven districts of Punjab. Consequently, we are unable to fully generalize the findings of our study to the rest of country. Moreover, we employed a convenient sampling technique that can be associated with bias. However, in view of the characteristics of the Punjab region in Pakistan, coupled with our methodology, we believe our findings are robust for Pakistan and can be helpful with improving the appropriate use of antibiotics within ambulatory care facilities in Pakistan. We will be looking to take this research forward in future studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Setting and Design

The Department of Health of the Punjab government has two divisions, of which the first is the Specialized Health and Medical Education Department, that is the controlling authority of tertiary/teaching hospitals, mainly established in metropolitan cities of the province and serve as referral hospitals. The second division is the Ambulatory and Secondary Healthcare Department, comprising of secondary hospitals, including district headquarters (DHQs), tehsil headquarters (THQs), ambulatory care health settings including rural health centers (RHCs), and basic health units (BHUs).

There are currently 358 RHCs in Punjab, each comprising approximately 20–25 beds, operating 24/7, and serving around a 100,000 nearby population. More than 2857 BHUs currently provide services in the province, with each Union Council having at least one BHU, with 2–5 beds, serving 10,000 to 25,000 people [

72]. All BHUs and RHCs have ambulatory care physicians, nurses, and other technicians, including pharmacy technicians as staff members. Free medical checkups, medicines, and laboratory facilities are provided in these ambulatory healthcare facilities. Pharmacists are employed in tertiary, DHQ, and THQ hospitals, while pharmacy technicians are currently serving at ambulatory health care facilities. These pharmacy technicians have a one-year educational diploma training, followed by further training under the supervision of a pharmacist or senior pharmacy technician after matriculation. Pharmacy technicians are responsible for the storage, distribution, dispensing, and administration of medicines.

We used a cross-sectional study design to collect data regarding knowledge of antibiotic use, AMR, and ASPs among pharmacy technicians, serving in ambulatory care facilities in the public sector of Punjab, over a two-month period (Feb–March 2022).

4.2. Study Sites

We collected data from pharmacy technicians from 37 RHCs and 107 BHUs from seven districts of Punjab out of 36 districts that were conveniently sampled. There were 2–3 pharmacy technicians at each BHU and 4–5 at each RHC.

4.3. Study Sample

The sample size was calculated using the Raosoft, 206-525-4025 (US), online sample size calculator [

73]. Assuming an expected frequency of 50%, at a 95% confidence interval, and 5% margin of error, the minimum sample size was calculated at 376.

Pharmacy technicians currently serving in the ambulatory health care department, government of Punjab, belonging to the seven districts (Sahiwal, Pakpattan, Okara, Qasor, Vehari, Bahawalnagar, and Multan) were included in the survey. As mentioned, these districts were selected using a convenient sampling technique. Pharmacy technicians working in the private sector, pharmacy technician students, and those working in other districts of Punjab were excluded from the current study as we wanted to concentrate initially in the public sector.

4.4. Development of the Study Instrument

The study tool used in our survey was adapted from previous studies conducted in the local population [

47,

48] as well as a review of the literature. The initial draft of the study instrument was prepared by the leading investigators (ZUM and MS). Pilot testing was subsequently conducted among 20 pharmacy technicians from eight ambulatory health care facilities of two districts to verify the clarity and understanding of the content, to enhance its robustness. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated based on the results of the pre-testing of the questionnaire in order to determine its reliability. The value of Cronbach’s alpha was higher than seven, which indicates an acceptable level of internal consistency. The participants from the pilot study were not included in the principal study.

Based on the outcome of the pilot study, minor amendments were made to the questionnaire. This resulted in a final study instrument comprising five sections.

Section S1 covered the demographic characteristics of the study population. Ten questions were included in this section incorporating age, city, sex, marital status, residence, designation, status of training, working department, years of experience, and the number of prescriptions filled per day.

Section S2 consisted of nine questions, including questions regarding perspectives of antibiotic use among study participants. Each question had three options, namely ‘Yes’, ‘No’, and ‘Do not know’. Participants were requested to select one option out of the three based on their knowledge.

Section S3 contained eight questions about participants’ understanding of AMR. Pharmacy technicians were asked to choose one correct option from ‘Yes’, ‘No’, and ‘Unsure’.

Section S4 covered awareness of different terminologies related to AMR, including antibiotic resistance, superbugs, and extensively drug resistance infections. This section consisted of nine questions and participants were asked to choose ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ according to their awareness about certain terminology.

Section S5 contained five questions about knowledge of ASPs, requiring participants to select one option from ‘Yes’, ‘No’, and ‘Unsure’. The last question asked participants about their source/s of information about infections and antibiotics, including social media, health care professionals, and leaflets/brochures included with the antibiotic packs dispensed.

4.5. Data Collection Procedures

The data collection tool was distributed among pharmacy technicians during duty hours (8:00 to 16:00) with a request to complete the questionnaire in a timely manner. The pharmacy technicians were provided with study instruments, and these were collected after half an hour in a sealed box. Participation in the study was entirely voluntary and anonymous. Potential study participants were firstly briefed about the purpose of the study prior to their enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and anyone could leave the survey at any time of data collection.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

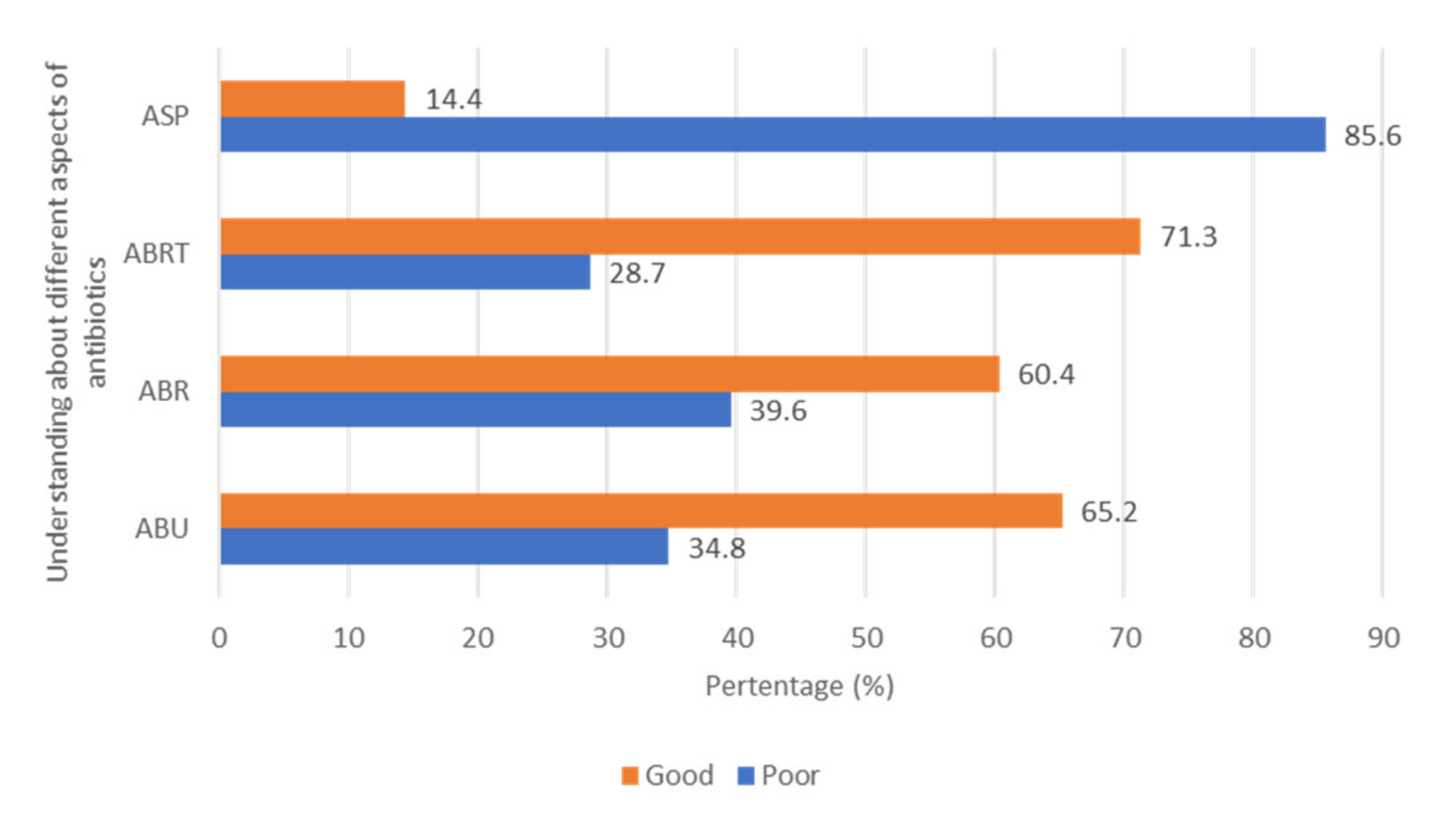

Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, were used to analyze the data. Moreover, the normality of the data was checked through Shapiro–Wilks and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. One mark was allocated for each correct response against the understanding of respondents towards different aspects of antibiotics, with no marks given for incorrect or unsure responses. Based on the median score, the outcomes regarding the understanding of respondents towards ABU (antibiotic use), ABR (antibiotic resistance), ABT (antibiotic terminologies), ASP (antimicrobial stewardship program) were dichotomized as “Good” versus “Poor” (

Table 7). The median score was calculated from the sum of the total score of the respondents in each domain, similar to the methodology used by Horvat et al. (2017) [

74].

Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U Test and Independent Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test were performed to test if there were differences among characteristics of the pharmacy technicians with regard to their attitudes, perceptions, willingness, and motivation towards PBR. All data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., version 18, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.