Melatonin as an Antimicrobial Adjuvant and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

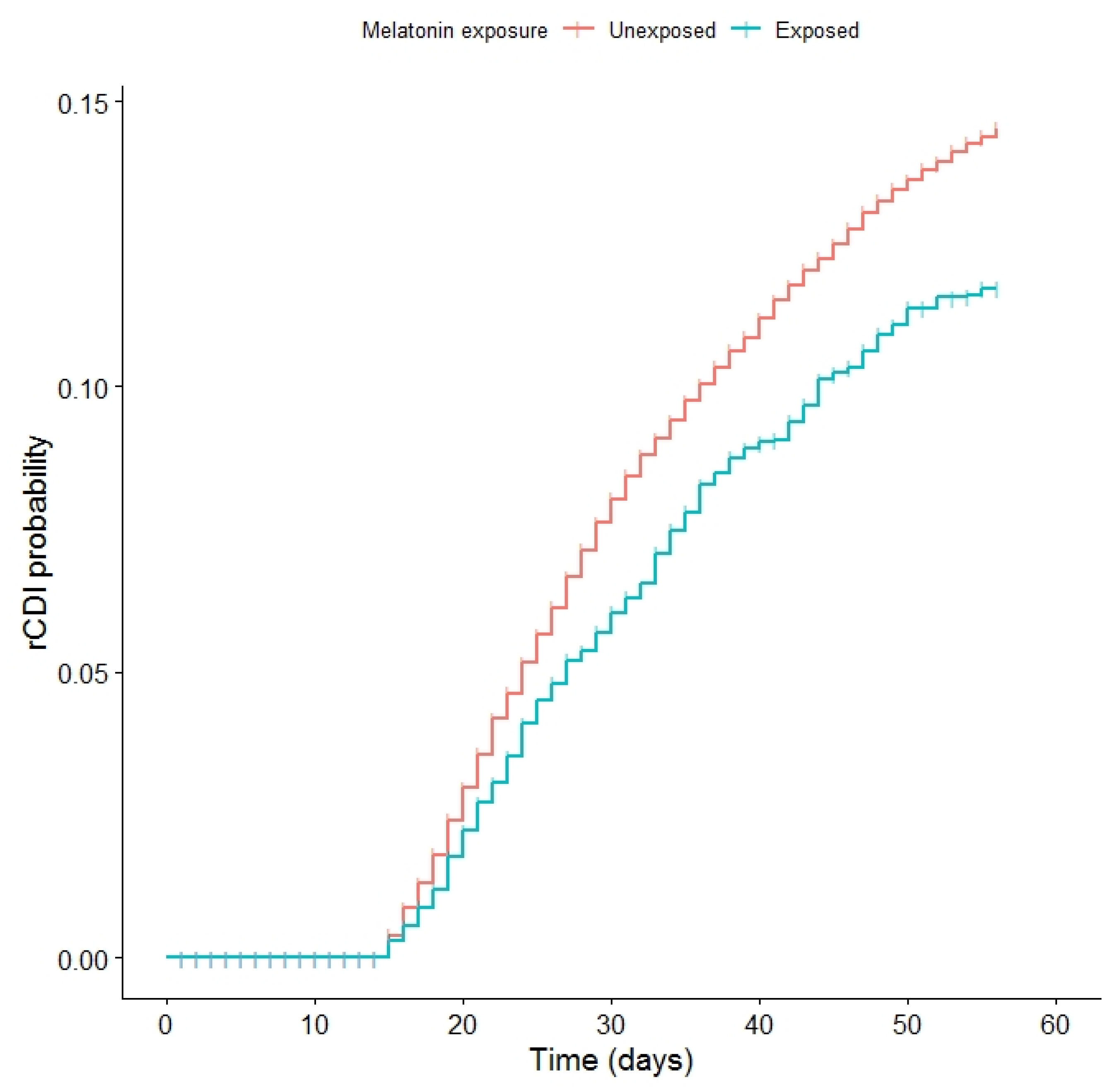

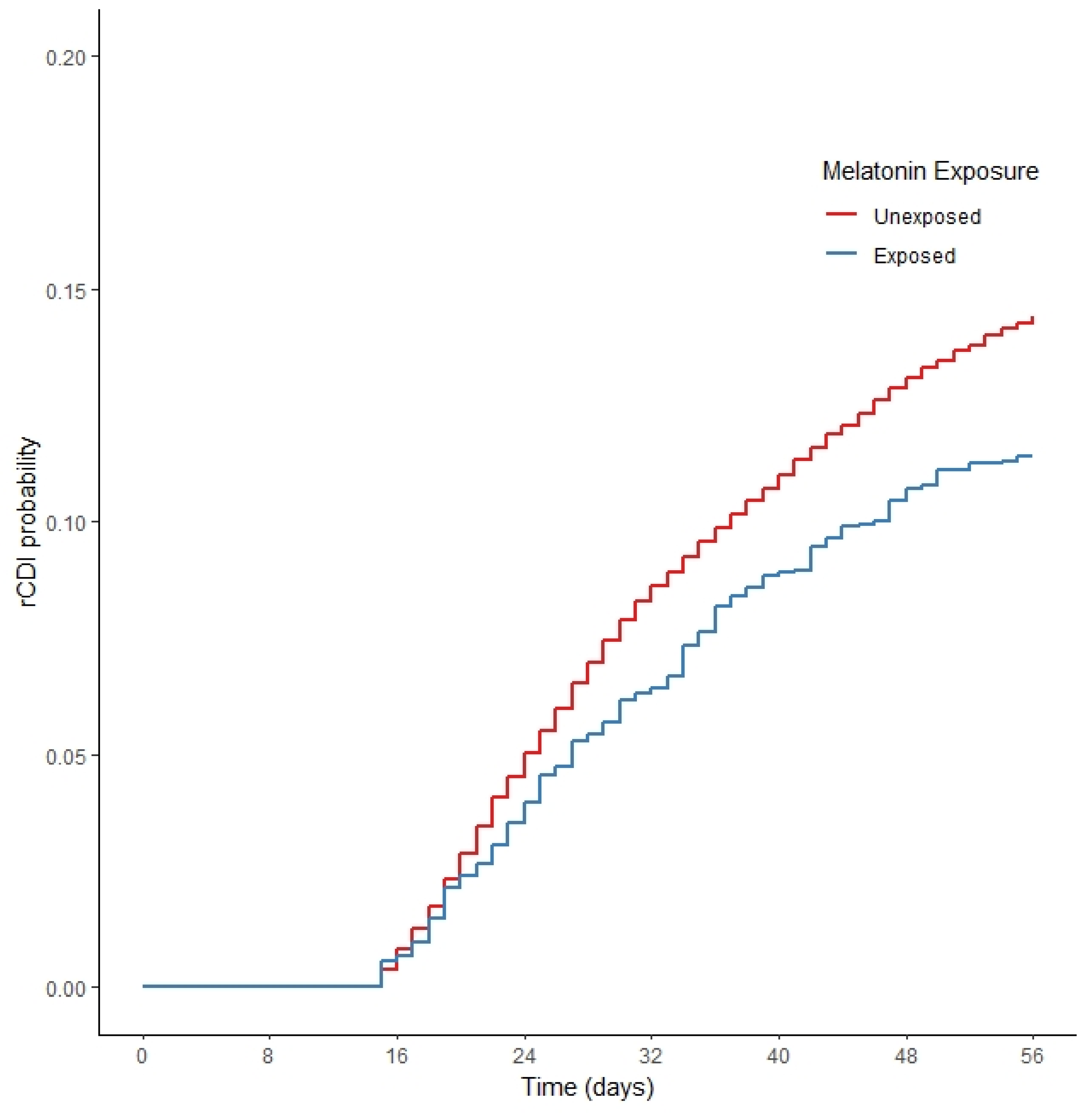

2.2. Cox Proportional Hazards Models

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Cohort Creation

4.3. Study Outcome

4.4. Exposure Definition

4.5. Covariate Data

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schäffler, H.; Breitrück, A. Clostridium difficile-From colonization to infection. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, C.P.; Pothoulakis, C.; LaMont, J.T. Clostridium difficile colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinlen, L.; Ballard, J.D. Clostridium difficile infection. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 340, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubberke, E.R.; Olsen, M.A. Burden of clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55 (Suppl. 2), S88–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guh, A.Y.; Mu, Y.; Winston, L.G.; Johnston, H.; Olson, D.; Farley, M.M.; Wilson, L.E.; Holzbauer, S.M.; Phipps, E.C.; Dumyati, G.K.; et al. Trends in U.S. Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection and Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1320–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, E.; Andersson, F.L.; Madin-Warburton, M. Burden of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI)—A systematic review of the epidemiology of primary and recurrent CDI. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriot, C.M.; Koenigsknecht, M.J.; Carlson, P.E.; Hatton, G.E.; Nelson, A.M.; Li, B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Li, J.Z.; Young, V.B. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kociolek, L.K.; Gerding, D.N. Breakthroughs in the treatment and prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.P.; LaMont, J.T. Clostridium difficile—More Difficult Than Ever. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “What Is C. Diff?” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Dilnessa, T.; Getaneh, A.; Hailu, W.; Moges, F.; Gelaw, B. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of Clostridium difficile among hospitalized diarrheal patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigaglia, P.; Mastrantonio, P.; Barbanti, F. Antibiotic resistances of Clostridium difficile. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 2050, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, H. Non-antibiotic therapy for Clostridioides difficile infection: A review. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2019, 56, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkoh, C.; Deaton, M.; Dupont, H.L. Nonantimicrobial drug targets for Clostridium difficile infections. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacyshyn, M.B.; Yacyshyn, B. The role of gut inflammation in recurrent clostridium difficile-associated disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1722–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rao, K.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Walk, S.T.; Micic, D.; Falkowski, N.; Santhosh, K.; Mogle, J.A.; Ring, C.; Young, V.B.; Huffnagle, G.B.; et al. The systemic inflammatory response to clostridium difficile infection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Low, Z.Y.; Farouk, I.A.; Lal, S.K. Drug repositioning: New approaches and future prospects for life-debilitating diseases and the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Viruses 2020, 12, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Q.; Fichna, J.; Bashashati, M.; Li, Y.Y.; Storr, M. Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3888–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.Z.; Gwee, K.A.; Moochhalla, S.; Ho, K.Y. Melatonin improves bowel symptoms in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 22, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.Q.; Zhang, X.M. Melatonin reduces inflammation in intestinal cells, organoids and intestinal explants. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arioz, B.I.; Tarakcioglu, E.; Olcum, M.; Genc, S. The role of melatonin on nlrp3 inflammasome activation in diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomini, F.; dos Santos, M.; Veronese, F.V.; Rezzani, R. NLRP3 inflammasome modulation by melatonin supplementation in chronic pristane-induced lupus nephritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.; Son, M.; Cheon, J.H.; Park, Y.S. Melatonin controls microbiota in colitis by goblet cell differentiation and antimicrobial peptide production through Toll-like receptor 4 signalling. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Filippis, D.; Iuvone, T.; Esposito, G.; Steardo, L.; Arnold, G.H.; Paul, A.P.; De Joris, G.; De Benedicte, Y. Melatonin reverses lipopolysaccharide-induced gastro-intestinal motility disturbances through the inhibition of oxidative stress. J. Pineal Res. 2008, 44, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.H.; Yu, J.P.; Yu, H.G.; Xu, X.M.; Yu, L.L.; Liu, J.; Luo, H.S. Melatonin reduces inflammatory injury through inhibiting NF-κβ activation in rats with colitis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2005, 2005, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y.; Hardeland, R.; Xia, Y. Bacteriostatic Potential of Melatonin: Therapeutic Standing and Mechanistic Insights. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 683879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.A.; Stwalley, D.; Demont, C.; Dubberke, E.R. Clostridium difficile infection increases acute and chronic morbidity and mortality. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Prabhu, V.S.; Marcella, S.W. Attributable Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs for Patients with Primary and Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarrad, A.M.; Karoli, T.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Lyras, D.; Cooper, M.A. Clostridium difficile Drug Pipeline: Challenges in Discovery and Development of New Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5164–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reiter, R.J.; Calvo, J.R.; Karbownik, M.; Qi, W.; Tan, D.X. Melatonin and Its Relation to the Immune System and Inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 917, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Bhutani, S.; Kim, C.H.; Irwin, M.R. Anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 93, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantounou, M.; Plascevic, J.; Galley, H.F. Melatonin and Related Compounds: Antioxidant and Inflammatory Actions. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, R.A.; Young, V.B. Interaction between the intestinal microbiota and host in Clostridium difficile colonization resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bien, J.; Palagani, V.; Bozko, P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: Is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, J.; Hirota, S.A.; Gross, O.; Li, Y.; Ulke-Lemee, A.; Potentier, M.S.; Schenck, L.P.; Vilaysane, A.; Seamone, M.E.; Feng, H.; et al. Clostridium difficile toxin-induced inflammation and intestinal injury are mediated by the inflammasome. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangan, M.S.J.; Gorki, F.; Krause, K.; Heinz, A.; Ebert, T.; Jahn, D.; Hiller, K.; Hornung, V.; Mauer, M.; Schmidt, F.I.; et al. Clostridium difficile Toxin B activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages, demonstrating a novel regulatory mechanism for the Pyrin inflammasome. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowardin, C.A.; Kuehne, S.A.; Buonomo, E.L.; Marie, C.S.; Minton, N.P.; Petri, W.A. Inflammasome activation contributes to interleukin-23 production in response to Clostridium difficile. mBio 2015, 6, e02386-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattana, M.; Tomasello, R.; Cammarata, C.; di Carlo, P.; Fasciana, T.; Giordano, G.; Lucchesi, A.; Siragusa, S.; Napolitano, M. Clostridium difficile Induced Inflammasome Activation and Coagulation Derangements. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.; Lynch, M.; Smith, S.M.; Amu, S.; Nel, H.J.; McCoy, C.E.; Dowling, J.K.; Draper, E.; O’Reilly, V.; McCarthy, C.; et al. A role for TLR4 in clostridium difficile infection and the recognition of surface layer proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knippel, R.J.; Zackular, J.P.; Moore, J.L.; Celis, A.I.; Weiss, A.; Washington, M.K.; DuBois, J.L.; Caprioli, R.M.; Skaar, E.P. Heme sensing and detoxification by HatRT contributes to pathogenesis during Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beavers, W.N.; Weiss, A.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Edmonds, K.A.; Giedroc, D.P.; Skaar, E.P. Clostridioides difficile Senses and Hijacks Host Heme for Incorporation into an Oxidative Stress Defense System. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 411–421.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Unexposed, N = 21,325 | Melatonin-Exposed, N = 3457 | p-Value | Standardized Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.34(13.8) | 69.91(12.87) | 0.023 | 0.042 | |

| Sex | Female | 801(3.76%) | 125(3.62%) | 0.722 | 0.007 |

| Male | 20524(96.24%) | 3332(96.38%) | 0.722 | 0.007 | |

| Race | Black | 3713(17.41%) | 493(14.26%) | <0.001 | 0.084 |

| Other/unknown | 1367(6.41%) | 231(6.68%) | <0.001 | 0.011 | |

| White | 16245(76.18%) | 2733(79.06%) | <0.001 | 0.068 | |

| BMI | <18.5 | 1323(6.2%) | 188(5.44%) | 0.01 | 0.032 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 7139(33.48%) | 1113(32.2%) | 0.01 | 0.027 | |

| 25–29.9 | 6030(28.28%) | 985(28.49%) | 0.01 | 0.005 | |

| 30+ | 6026(28.26%) | 1004(29.04%) | 0.01 | 0.017 | |

| Missing | 807(3.78%) | 167(4.83%) | 0.01 | 0.054 | |

| Charlson | 4.25(3.32) | 4.9(3.45) | <0.001 | 0.194 | |

| Level of care | Acute care | 18184(85.27%) | 2838(82.09%) | <0.001 | 0.089 |

| Sub-acute care | 3141(14.73%) | 619(17.91%) | <0.001 | 0.089 | |

| C. difficile treatment | Fidaxomicin(fid) | 51(0.24%) | 25(0.72%) | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Metronidazole(met) | 13301(62.37%) | 685(19.81%) | <0.001 | 0.858 | |

| Vancomycin+fid+met | #(#) a | 0(0%) | <0.001 | 0.01 | |

| Vancomycin | 6690(31.37%) | 2583(74.72%) | <0.001 | 0.896 | |

| Vancomycin+met | 1281(6.01%) | 164(4.74%) | <0.001 | 0.054 | |

| Leukocytosis | 3739(17.53%) | 550(15.91%) | 0.021 | 0.043 | |

| Albumin <3.4 mg/dL | 272(1.28%) | 71(2.05%) | <0.001 | 0.067 | |

| Serum creatinine >1.5 | 4229(19.83%) | 721(20.86%) | 0.169 | 0.026 | |

| Recurrent CDI | 2779 (13.03%) | 376 (10.8%) | <0.001 |

| Unweighted | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | |

| Melatonin | 0.841 (0.751–0.943) | |

| Age | 1.008 (1.006–1.011) | |

| Sex | Male vs. female | 1.182 (0.961–1.455) |

| Race | Other/unknown vs. black | 1.047 (0.882–1.243) |

| White vs. black | 1.184 (1.071–1.309) | |

| BMI | 18.5–24.9 vs. <18.5 | 0.964 (0.83–1.12) |

| 25–29.9 vs. <18.5 | 0.806 (0.691–0.941) | |

| 30+ vs. <18.5 | 0.843 (0.723–0.983) | |

| Missing vs. <18.5 | 1.077 (0.872–1.33) | |

| Charlson | 1.022 (1.011–1.033) | |

| Level of care | Sub-acute vs. acute care | 2.016 (1.857–2.188) |

| C. difficile treatment | Metronidazole vs. fidaxomicin | 0.668 (0.414–1.079) |

| van+fid+met vs. fidaxomicin | 0 (--) * | |

| Vancomycin vs. fidaxomicin | 0.517 (0.32–0.835) | |

| Vancomycin+metronidazole vs. fidaxomicin | 0.665 (0.405–1.094) | |

| Leukocytosis | 1.36 (1.24–1.491) | |

| Albumin <3.4 mg/dL | 0.849 (0.581–1.242) | |

| Serum creatinine >1.5 | 1.025 (0.934–1.124) |

| Variable | Unexposed | Melatonin-Exposed | Standardized Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.424 | 69.25 | 0.013 | |

| Sex | Female | 4% | 4% | 0 |

| Male | 96% | 96% | 0 | |

| Race | Black | 17% | 17% | 0.01 |

| Other/unknown | 6% | 6% | 0.001 | |

| White | 77% | 77% | 0.01 | |

| BMI | <18.5 | 6% | 5% | 0.058 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 33% | 33% | 0.016 | |

| 25–29.9 | 28% | 29% | 0.008 | |

| 30+ | 28% | 30% | 0.036 | |

| Missing | 4% | 4% | 0.007 | |

| Charlson | 4.335 | 4.333 | 0 | |

| Level of care | Acute care | 85% | 84% | 0.031 |

| Sub-acute care | 15% | 16% | 0.031 | |

| C. difficile treatment | Fidaxomicin(fid) | 0% | 0% | 0.003 |

| Metronidazole(met) | 57% | 54% | 0.058 | |

| Vancomycin +fid+met | 0% | 0% | 0.009 | |

| Vancomycin | 37% | 40% | 0.061 | |

| Vancomycin+met | 6% | 6% | 0.003 | |

| Leukocytosis | 17% | 14% | 0.082 | |

| Albumin <3.4 mg/dL | 1% | 1% | 0.008 | |

| Serum creatinine >1.5 | 20% | 20% | 0.009 |

| Propensity-Score-Weighted | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | |

| Melatonin | 0.784 (0.674–0.912) | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.006–1.014) | |

| Sex | Male vs. female | 0.914 (0.612–1.366) |

| Race | Other/unknown vs. black | 1 (0.733–1.364) |

| White vs. black | 1.255 (1.035–1.523) | |

| BMI | 18.5–24.9 vs. <18.5 | 0.859 (0.66–1.119) |

| 25–29.9 vs. <18.5 | 0.733 (0.558–0.964) | |

| 30+ vs. <18.5 | 0.742 (0.568–0.97) | |

| Missing vs. <18.5 | 0.967 (0.671–1.393) | |

| Charlson | 1.034 (1.013–1.055) | |

| Level of care | Sub-acute vs. acute care | 1.832 (1.576–2.13) |

| C. difficile treatment | Metronidazole vs. fidaxomicin | 0.417 (0.253–0.687) |

| van+fid+met vs. fidaxomicin | 0 (0–0) | |

| Vancomycin vs. fidaxomicin | 0.335 (0.204–0.548) | |

| Vancomycin+metronidazole vs. fidaxomicin | 0.41 (0.241–0.698) | |

| Leukocytosis | 1.2 (1.016–1.416) | |

| Albumin < 3.4 mg/dL | 0.71 (0.466–1.084) | |

| Serum creatinine > 1.5 | 1.046 (0.873–1.252) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sutton, S.S.; Magagnoli, J.; Cummings, T.H.; Hardin, J.W. Melatonin as an Antimicrobial Adjuvant and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111472

Sutton SS, Magagnoli J, Cummings TH, Hardin JW. Melatonin as an Antimicrobial Adjuvant and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Antibiotics. 2022; 11(11):1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111472

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutton, S. Scott, Joseph Magagnoli, Tammy H. Cummings, and James W. Hardin. 2022. "Melatonin as an Antimicrobial Adjuvant and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection" Antibiotics 11, no. 11: 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111472

APA StyleSutton, S. S., Magagnoli, J., Cummings, T. H., & Hardin, J. W. (2022). Melatonin as an Antimicrobial Adjuvant and Anti-Inflammatory for the Management of Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Antibiotics, 11(11), 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11111472