The Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Infections Caused by Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

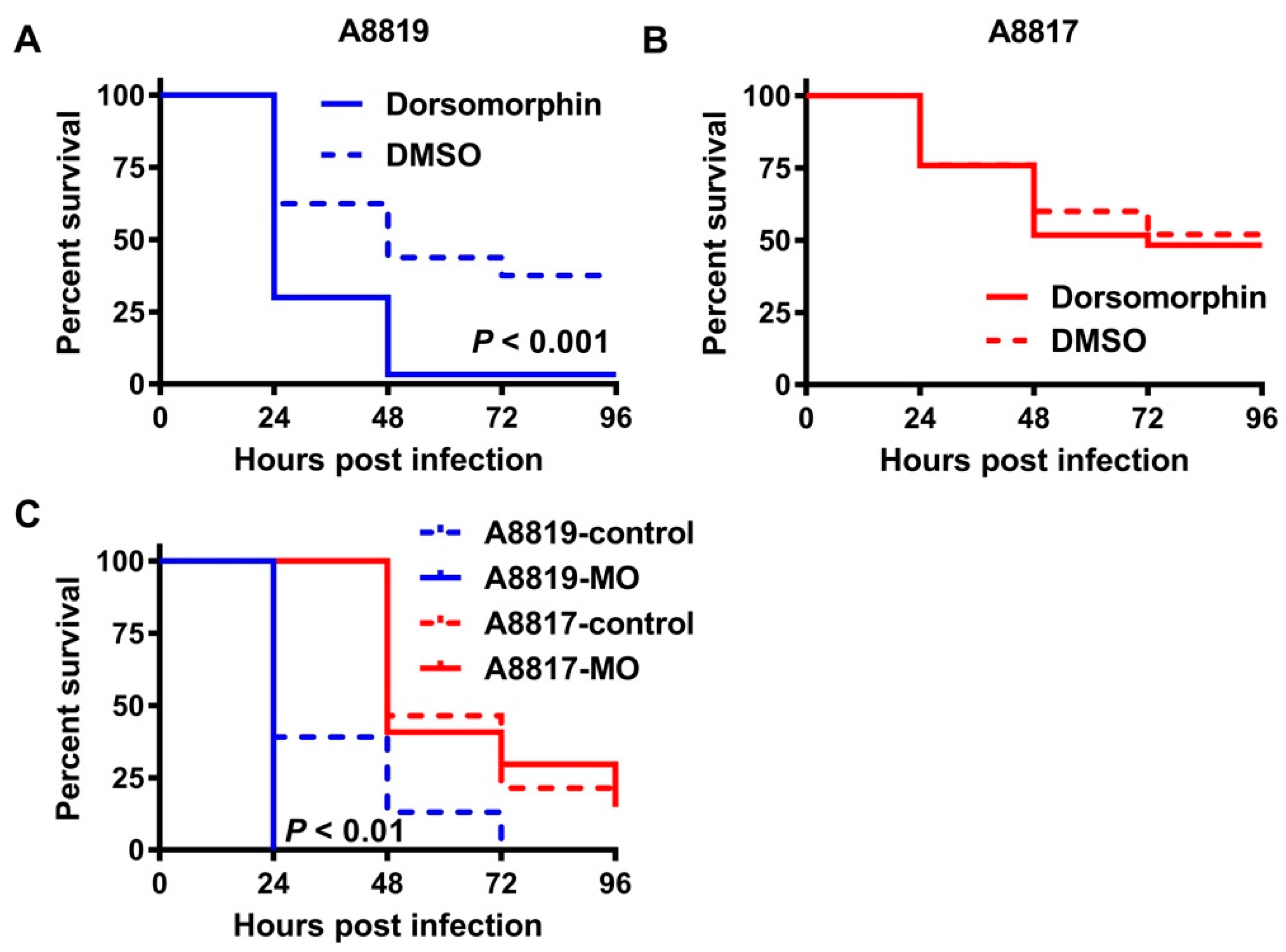

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Culture of Bacterial Strains and Human Neutrophil Peptide 1 (hNP-1) Killing Assay

4.2. Ex Vivo Human Whole Blood Killing Assay

4.3. Zebrafish Infection, Leukocyte Enumeration and Survival Analyses

4.4. Inhibition of the Antimicrobial Peptide Hepcidin In Vivo

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, A.S.; de Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, J.M.; Mills, R.H.; Olson, J.; Caldera, J.R.; Sepich-Poore, G.D.; Carrillo-Terrazas, M.; Tsai, C.M.; Vargas, F.; Knight, R.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Mortality Risk Profiling of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia by Multi-omic Serum Analysis Reveals Early Predictive and Pathogenic Signatures. Cell 2020, 182, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paling, F.P.; Hazard, D.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Goossens, H.; Jafri, H.S.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Sifakis, F.; Weber, S.; Kluytmans, J.; Team, A.-I.S. Association of Staphylococcus aureus Colonization and Pneumonia in the Intensive Care Unit. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Boucher, H.W.; Corey, G.R.; Abrutyn, E.; Karchmer, A.W.; Rupp, M.E.; Levine, D.P.; Chambers, H.F.; Tally, F.P.; Vigliani, G.A.; et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holubar, M.; Meng, L.; Alegria, W.; Deresinski, S. Bacteremia due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An Update on New Therapeutic Approaches. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.L.; Arnold, C.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A review. JAMA J. Am. Med Assoc. 2014, 312, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, A.S.; Schneider, T.; Sahl, H.G. Mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: Role of the cell membrane and cell wall. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1277, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Munita, J.M.; Arias, C.A. Mechanisms of drug resistance: Daptomycin resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1354, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, A.Y.; Miyakis, S.; Ward, D.V.; Earl, A.M.; Rubio, A.; Cameron, D.R.; Pillai, S.; Moellering, R.C., Jr.; Eliopoulos, G.M. Whole genome characterization of the mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in clinical and laboratory derived isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e28316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.R.; Mortin, L.I.; Rubio, A.; Mylonakis, E.; Moellering, R.C., Jr.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Peleg, A.Y. Impact of daptomycin resistance on Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Virulence 2015, 6, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglialegna, A.; Varela, M.C.; Rosato, R.R.; Rosato, A.E. VraSR and Virulence Trait Modulation during Daptomycin Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection. mSphere 2019, 4, e00557-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Fitness Cost of Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Obtained from in vitro Daptomycin Selection Pressure. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, R.L.; Haigh, R.D.; Pascoe, B.; Sheppard, S.K.; Price, F.; Jenkins, D.; Rajakumar, K.; Morrissey, J.A. Persistent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from two independent bacteraemia display increased bacterial fitness and novel immune evasion phenotypes. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 3311–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haney, E.F.; Straus, S.K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Reassessing the Host Defense Peptide Landscape. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.E.; Sahl, H.G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chertov, O.; Bykovskaia, S.N.; Chen, Q.; Buffo, M.J.; Shogan, J.; Anderson, M.; Schroder, J.M.; Wang, J.M.; Howard, O.M.; et al. Beta-defensins: Linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science 1999, 286, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizet, V.; Ohtake, T.; Lauth, X.; Trowbridge, J.; Rudisill, J.; Dorschner, R.A.; Pestonjamasp, V.; Piraino, J.; Huttner, K.; Gallo, R.L. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature 2001, 414, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Hata, T.; Bapat, S.P.; Ramos, R.; Plikus, M.V.; Gallo, R.L. Innate immunity. Dermal adipocytes protect against invasive Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Science 2015, 347, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Fisher, E.L.; McCausland, J.W.; Choi, J.; Collins, J.W.M.; Dickey, S.W.; Otto, M. Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance Mechanism Contributes to Staphylococcus aureus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Yeaman, M.R.; Sakoulas, G.; Yang, S.J.; Proctor, R.A.; Sahl, H.G.; Schrenzel, J.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Bayer, A.S. Failures in clinical treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Infection with daptomycin are associated with alterations in surface charge, membrane phospholipid asymmetry, and drug binding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.N.; McKinnell, J.; Yeaman, M.R.; Rubio, A.; Nast, C.C.; Chen, L.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Bayer, A.S. In vitro cross-resistance to daptomycin and host defense cationic antimicrobial peptides in clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4012–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.H.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; Shen, H.H.; Cameron, D.R.; Rupasinghe, T.W.T.; Wu, C.M.; Le Brun, A.P.; Kostoulias, X.; Domene, C.; Fulcher, A.J.; et al. Antibiotic resistance and host immune evasion in Staphylococcus aureus mediated by a metabolic adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3722–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepburn, L.; Prajsnar, T.K.; Klapholz, C.; Moreno, P.; Loynes, C.A.; Ogryzko, N.V.; Brown, K.; Schiebler, M.; Hegyi, K.; Antrobus, R.; et al. Innate immunity. A Spaetzle-like role for nerve growth factor beta in vertebrate immunity to Staphylococcus aureus. Science 2014, 346, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.B.; Hong, C.C.; Sachidanandan, C.; Babitt, J.L.; Deng, D.Y.; Hoyng, S.A.; Lin, H.Y.; Bloch, K.D.; Peterson, R.T. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Valore, E.V.; Waring, A.J.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7806–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, C.M.; Gallo, R.L.; Finlay, B.B. Interplay between antibacterial effectors: A macrophage antimicrobial peptide impairs intracellular Salmonella replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2422–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhuiyan, M.S.; Jiang, J.-H.; Kostoulias, X.; Theegala, R.; Lieschke, G.J.; Peleg, A.Y. The Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Infections Caused by Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10020096

Bhuiyan MS, Jiang J-H, Kostoulias X, Theegala R, Lieschke GJ, Peleg AY. The Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Infections Caused by Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(2):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10020096

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhuiyan, Md Saruar, Jhih-Hang Jiang, Xenia Kostoulias, Ravali Theegala, Graham J. Lieschke, and Anton Y. Peleg. 2021. "The Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Infections Caused by Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus" Antibiotics 10, no. 2: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10020096

APA StyleBhuiyan, M. S., Jiang, J.-H., Kostoulias, X., Theegala, R., Lieschke, G. J., & Peleg, A. Y. (2021). The Resistance to Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Infections Caused by Daptomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics, 10(2), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10020096