“If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?”: A Qualitative Investigation of Antibiotic Use in Smallholder Livestock Settings in Rural West Bengal, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.1.1. Livestock Keeping Practices

2.1.2. Livestock Antibiotic Providers

“If you ask me now how you are practicing, we are only supposed to do vaccination, and artificial insemination. But if we did just that we won’t make enough money, so we, on our own, have learnt how to use antibiotics from other veterinary doctors”.Public-private VPP1, Site 1

2.1.3. Antibiotic Use in Livestock

“In primary cases enrofloxacin or sulfadiazine or oxytetracycline get most of the work done! Then the latest ones like ofloxacin, ceftazidime [third generation cephalosporin] are for quicker action (…). The client that can afford it, we give them a bit more expensive antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, ceftiofur [third generation cephalosporins], ofloxacin (…). If it doesn’t work, we change it to higher [power] antibiotics after three days”.Veterinary drug shop 1, Site 1

“People of [village in Site 1] are mostly poor (…) So, sometime even if the doctor [animal health practitioner] has given [prescribed] medicine for seven days, they would take medicines for two days”.Human drug shop 1, Site 1

2.1.4. Antibiotic Knowledge in Livestock Keepers

“We are illiterate people. We can’t read or write. How can we remember the names [of the medicines]?”LK1, Site 1

2.1.5. Antibiotic Knowledge in Livestock Healthcare Providers

“Now the food that’s given to the animals aren’t nutritious enough because everything is made artificially. So, the antibiotics aren’t working anymore. The resistance is growing”.Public-private VPP 2, Site 1

“We provide antibiotic in viral disease to prevent the secondary bacterial infection”.Veterinarian 4, Site 2

2.2. Drivers of Antibiotic Usage in Livestock

2.2.1. Antibiotics as Therapeutic Treatment

“Only when there’s a problem then [people use antibiotics], else not on a regular basis”.Key informant 2, Site 1

2.2.2. Antibiotics as Protection against Disease in Poultry

“If we follow this voucher [schedule] and give medication, Ranikhet [Newcastle disease] is prevented (…) If we follow that [the schedule], disease don’t come easily”.LK26, Site 2

“I also try to prevent the diseases. For example, BQ [blackquarter, a vaccine-preventable clostridial disease], FMD [Foot and Mouth Disease, a viral disease] harm the cow’s health a lot. And the treatment is also quite costly. And you have to give antibiotics. So, we give treatment in advance!”Public-private VPP 2, Site 1

2.2.3. Lack of Diagnostic Certainty Leads to Heuristics

“In case of cows we measure the temperature using the thermometer in the rectum. And if the cows have cough, or cold, has respiratory infection, we use drugs from the ampicillin group (…) there is no system here to get the blood of the cow tested. It doesn’t happen in this country (…)”.Public-private VPP 1, Site 1

“No, I don’t see the animals. I base my diagnosis on what the client is saying. I use my experience to understand what the clients are trying to say and what might have happened. They are not always right (…)”.Veterinary drug shop 1, Site 1

“Mainly they [healthcare providers] use what they have with them. If they have oxytetracycline, they use it on every animal. They don’t diagnose whether it is bacterial or viral. If he has enrofloxacin he uses enrofloxacin for all animals”.Veterinarian 4, Site 2

2.2.4. Antibiotic Usage to Beat Competition and Retain Business

“With regard to treatment, antibiotics are used more than it was before. Antibiotics should be used as less as possible. But we have to use it still, because of the competition. If we can cure the patient fast, then they would call me. If it takes such a long time, they will want to seek other doctors (…)”.Public-private VPP 2, Site 1

2.2.5. Promotion and Incentives by Pharmaceutical Companies

“Here the small dairy farmer use antibiotic themselves. They use penicillin and strepto-penicillin randomly without taking any suggestions (…) I can’t say how much they are using. We forbid them to use antibiotic unnecessarily. But the medicine companies goes there and making them understand if cow is in cough and cold, give this antibiotic course, give this with that etc; they make them understand. If they come to us, I say if it is not sick no need to give it (antibiotic). But most of the time, if any sort of cough-cold seen they use penicillin, strepto-penicillin, amoxicillin, ampicillin”.Veterinarian 1, Site 1

“They sometime come and tell that this new medicine works better in this condition. And I used that in field condition, if it works, I use it afterward (…) I am having phone number of them (like [name redacted] from [pharmaceutical company name]). Sometimes I call him, or he calls me. Whenever I am short of medicine, if I call him, he says that it could be available in this shop of [nearby town name redacted]”.Para-vet 2, Site 2

2.3. Deterrents to Using Antibiotics

Antibiotics Have Side Effects

“Once I used sulfa [sulfonamides] drugs for diarrhoea but there, abortion happened. So, I stopped using sulfa drug in diarrhoea cases”.Para-vet 2, Site 2

“I do not apply the potent [high power] antibiotics. I generally use easily available, safe antibiotics. In serious problem where it needs potent antibiotics, I refer to veterinary doctor”.Para-vet 1, Site 1

2.4. Crossover-Use of Antibiotics in Livestock

“No, they don’t give human medication. An animal doctor would give animal medication”.LK5, Site 1

“If it’s needed, I get it from the market [from human drugs shops]. We might prescribe it to the patient, and they get it. Sometimes we, ourselves, get it from the store”.Public-private VPP 1, Site 1

2.5. Drivers of Crossover-Use of Antibiotics in Livestock

2.5.1. Lack of Access to Veterinary Drugs

“There’s no veterinary medicine shop in this area. The nearest [veterinary] shop is 6 km away”.Human drug shop 1, Site 1

“In case my stock for the day is over, or I treated more patients than usual, it’d take a long time for me to go to [town name redacted], or to get it delivered from Kolkata. So, I will get the human medication from the store and get the work done”.Public-private VPP 2, Site 1

“They will ask, “how many animals do you have”. If we say 10–12, they say, “we don’t have it”. They say it to our faces. If you have 50–100 animals they would, then, give the medicines. For less than that they won’t open a file of medicines”.LK1, Site 1

2.5.2. Insufficient Veterinary Healthcare Capacity

“Suppose he [public-private VPP] is not there, and a person came to me and asked, “Doctor my goat is having loose motion, what can we do?” If I see the condition of the goat is really bad and it might die without a treatment, I may ask him to have a human medicine of a low dose (…) but if your animal dies then I may not be responsible”.IP5, Site 1

“Yes, sometimes when they have fever, we give the cows our medicines… Medicines for fever, or wounds. We don’t remember exactly. The power of medicines used in humans and animals are different. We [human medicine] have less power, the medicines used in cows have high power. If we use one medicine [dose] in humans, we will use two [doses] in the cows. That we see works. When we see that doctor isn’t coming, we do it…”LK1, Site 1

2.5.3. If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?

“Sometimes if we can’t buy medicines, and the goat has diarrhoea, we would use the diarrhoea medicine from the house for them to get well soon. It would probably work… We just think that if it works for humans, it might work in the cows for the same problem”.LK7, Site 1

“As much as I know, human antibiotics are 500 mg, or 250 mg, Ampicillin for example, but in case of cows, it’s 3 g or 3000 mg (…) I know this much that a cow would need a higher dosage. Both of them are of the same Ampicillin group, but veterinary medicine is very powerful, and human medicines are just 500 mg…”Public-private VPP 1, Site 1

2.5.4. Some Human Antibiotics Are Better

“Norfloxacin gets some better result in case of goat (…) When the norfloxacin is not available we use enrofloxacin (…) According to size and body weight (…) this type of medicine is available in the market in 200 mg and 400 mg preparation, in the case of adult goat we are using 400 mg like a human dose”.Veterinarian 5, Site 2

“I have seen some human medicine works very much in animal (…) I have seen in mastitis my medicine is not working but Clavam [amoxicillin clavulanate] works (…) Quality of human antibiotics is better”.Para-vet 3, Site 2

2.5.5. Higher Dosing Accuracy of Human Antibiotics in Small Livestock Species and Other Animals in the Household

“In cases of small animals, like dogs, goats etc. the veterinary antibiotics are of high power. For example, they are 3 g. I would need 1 g. So, I can’t use them, so I need to use human antibiotics”.Public-private VPP 1, Site 1

2.6. Deterrents to Using Human Antibiotics in Livestock

Perceptions of Livestock Keepers That Human Antibiotics Are Unsuitable for Use in Livestock

“We shouldn’t give human medicines to animals (…) It won’t suit them. If we take their medicines, it won’t suit us. If they take our medicines, it won’t suit them (…) We have a different stomach (…) that’s why it won’t suit”.LK2, Site 1

“The difference is that humans can talk, we can express which problems we have. But the animals can’t talk. We can feed the medicines, but they won’t be able to tell us if the medicine is causing a problem. We are scared that human medicines might harm animals”.LK4, Site 1

“To get medicines for humans we need to go to a different doctor and for the animals to a different one. (…) A man may have pox, similarly a cow or a chicken may have pox as well. Since the species are different, therefore medicines must be different as well. When a chicken has diarrhoea, the medicine is different than when a man has diarrhea”.LK10, Site 1

“No, we would never use human medicines on animals. The cow-tablet is this big, and the tablet for human is just this small. Of course, there’s a difference (…) The animal medicines have higher power”.LK3, Site 1

2.7. Crossover Use of Veterinary Antibiotics in People

2.8. Deterrents to Using Veterinary Antibiotics in People

2.8.1. Veterinary Antibiotics Have a Higher Power and Are Harmful to Humans

“(…) the medicine for the chickens are to be given to the chickens. Those who want to commit suicide, they would take such medicines”.LK10, Site 1

2.8.2. They Are ‘Not for Human Use’

“In veterinary antibiotic, it is written there that ‘not for human use’. There is no question of giving [to people]”.Para-vet 2, Site 2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

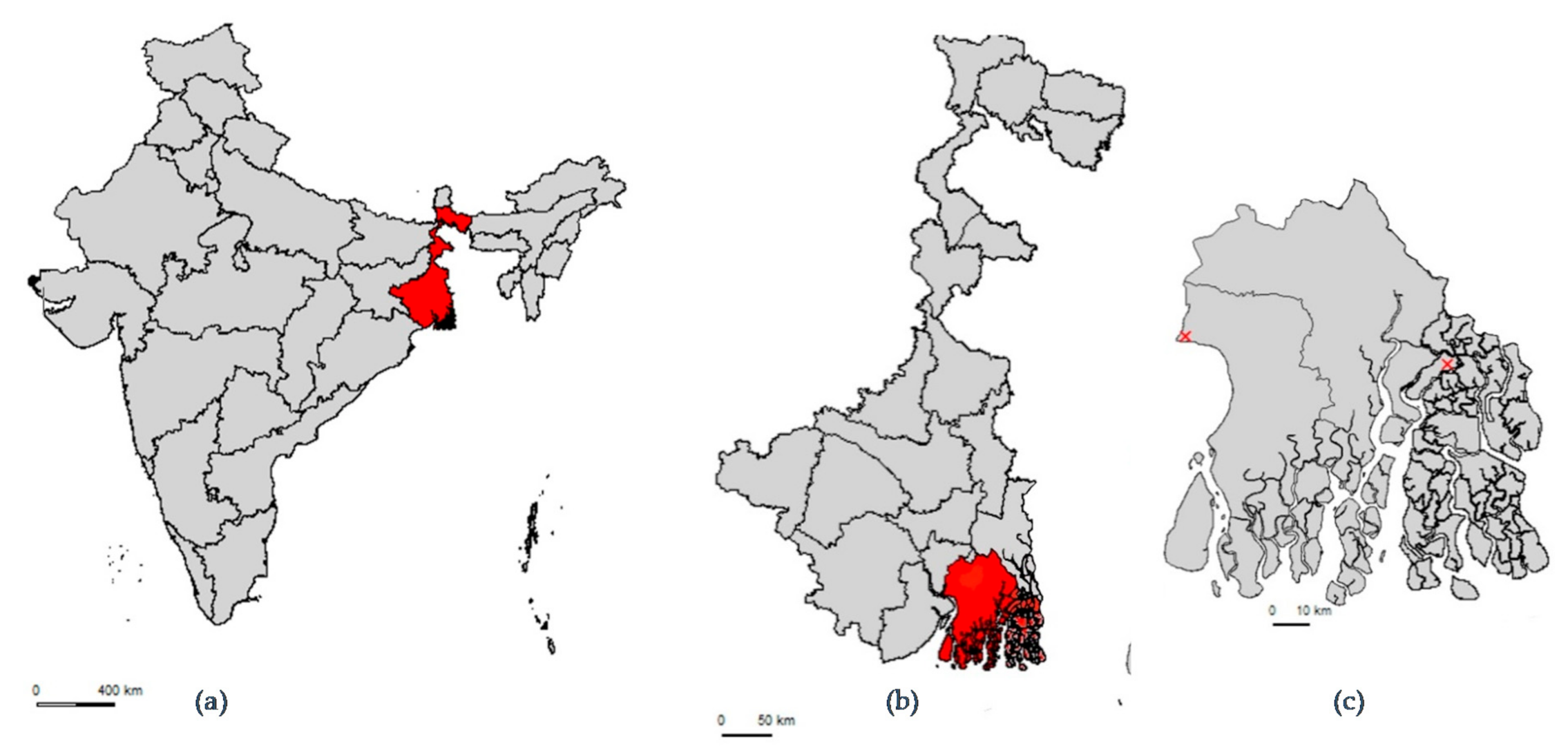

4.1. Study Setting

4.2. Selection of Participants

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Alvarez, L.; Dawson, S.; Cookson, B.; Hawkey, P. Working across the veterinary and human health sectors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, i37–i49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoelzer, K.; Wong, N.; Thomas, J.; Talkington, K.; Jungman, E.; Coukell, A. Antimicrobial drug use in food-producing animals and associated human health risks: What, and how strong, is the evidence? BMC Veter. Res. 2017, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The Evolving Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance: Options for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel, T.P.; Brower, C.; Gilbert, M.; Grenfell, B.T.; Levin, S.A.; Robinson, T.P.; Teillant, A.; Laxminarayan, R. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5649–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tang, K.L.; Caffrey, N.P.; Nóbrega, D.; Cork, S.C.; Ronksley, P.E.; Barkema, H.; Polachek, A.J.; Ganshorn, H.; Sharma, N.; Kellner, J.; et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e316–e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoHFW Government of India. Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Containment in India; WHO Country Office for India: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Dynamics Economics & Policy. Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Food Animals Current Policy and Recommendations; Center for Disease Dynamics Economics & Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gandra, S.; Joshi, J.; Trett, A.; Lamkang, A.S. Scoping Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in India; Center for Disease Dynamics Economics & Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Howard Batho, J.; Münstermann, S.; Woodford, J. OIE PVS Evaluation Mission Report India; World Organisation for Animal Health OIE: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Bi, Z.; Ma, S.; Chen, B.; Cai, C.; He, J.; Schwarz, S.; Sun, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; et al. Inter-host Transmission of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli among Humans and Backyard Animals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rao, S.; Rasheed Sulaiman, V.; Natchimuthu, K.; Ramkumar, S.; Sasidhar, P.; Gandhi, R. Improvement of Veterinary Services Delivery in India. Sci. Tech. Rev. 2015, 34, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.; Chander, M. Privatization of veterinary services in developing countries: A review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2003, 35, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.S.; George, M.S.; Chatterjee, P.; Lindahl, J.; Grace, D.; Kakkar, M. The social biography of antibiotic use in smallholder dairy farms in India. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, J. Prevailing practices in the use of antibiotics by dairy farmers in Eastern Haryana region of India. Veter. World 2018, 11, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, J.J.; Singh, K.M.; Bhatt, B.P.; Dey, A. A Diagnostic Study on Livestock Production System in Eastern Region of India. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 84, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Mutua, F.; Deka, R.P.; Shome, R.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Shome, B.; Kumar, N.G.; Grace, D.; Dey, T.K.; Venugopal, N.; et al. A qualitative study on antibiotic use and animal health management in smallholder dairy farms of four regions of India. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2020, 10, 1792033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautham, M.; Spicer, N.; Chatterjee, S.; Goodman, C. What are the challenges for antibiotic stewardship at the community level? An analysis of the drivers of antibiotic provision by informal healthcare providers in rural India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 275, 113813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimi, N.A.; Sultana, R.; Ishtiak-Ahmed, K.; Haider, N.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Nahar, N.; Luby, S.P. Where backyard poultry raisers seek care for sick poultry: Implications for avian influenza prevention in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roess, A.A.; Winch, P.J.; Akhter, A.; Afroz, D.; Ali, N.A.; Shah, R.; Begum, N.; Seraji, H.R.; Arifeen, S.; Darmstadt, G.L.; et al. Household Animal and Human Medicine Use and Animal Husbandry Practices in Rural Bangladesh: Risk Factors for Emerging Zoonotic Disease and Antibiotic Resistance. Zoonoses Public Health 2015, 62, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Chaudhury, R.R. Antibiotic Resistance in India: Drivers and Opportunities for Action. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gemeda, B.A.; Amenu, K.; Magnusson, U.; Dohoo, I.; Hallenberg, G.S.; Alemayehu, G.; Desta, H.; Wieland, B. Antimicrobial Use in Extensive Smallholder Livestock Farming Systems in Ethiopia: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Livestock Keepers. Front. Veter. Sci. 2020, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeiza, G.K.; Kabir, J.; Mamman, M.; Ibrahim, H.; Fagbamila, I. Response of Nigerian farmers to a questionnaire on chloramphenicol application in commercial layers. Vet Ital 2012, 48, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Om, C.; McLaws, M.-L. Antibiotics: Practice and opinions of Cambodian commercial farmers, animal feed retailers and veterinarians. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2016, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snively-Martinez, A.E. Ethnographic Decision Modeling to Understand Smallholder Antibiotic Use for Poultry in Guatemala. Med. Anthr. 2018, 38, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, K.D.; Ramatowski, J.W.; Buregyeya, E.; Hutchinson, E.; Kaur, H.; Mbonye, A.K.; Mateus, A.L.P.; Clarke, S.E. Unsafe “crossover-use” of chloramphenicol in Uganda: Importance of a One Health approach in antimicrobial resistance policy and regulatory action. J. Antibiot. 2021, 74, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guèye, E. Ethnoveterinary medicine against poultry diseases in African villages. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 1999, 55, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rousham, E.K.; Unicomb, L.; Islam, M.A. Human, animal and environmental contributors to antibiotic resistance in low-resource settings: Integrating behavioural, epidemiological and One Health approaches. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veterinary Medicines Directorate. Veterinary Medicines Guidance Note No 13-Guidance on the Use of Cascade; Veterinary Medicine Directorate: Addlestone, UK, 2013.

- Sandhu, H.; Rampal, S. Essential of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Kalyani Publishers: Ludhiana, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, I.; Joardar, S.N.; Mahanti, A.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Sar, T.K.; Dutta, T.K. Approaches to characterize extended spectrum beta-lactamase/beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in healthy organized vis-a-vis backyard farmed pigs in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 36, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCorkle, C.M. Back to the future: Lessons from ethnoveterinary RD&E for studying and applying local knowledge. Agric. Hum. Values 1995, 12, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Virhia, J.; Buza, J.; Crump, J.A.; de Glanville, W.A.; Halliday, J.E.B.; Lankester, F.; Mappi, T.; Mnzava, K.; Swai, E.S.; et al. “He Who Relies on His Brother’s Property Dies Poor”: The Complex Narratives of Livestock Care in Northern Tanzania. Front. Veter. Sci. 2021, 8, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAVS. Human Resource Needs in Veterinary and Animal Sciences; Policy Paper No. 2; National Academy of Veterinary Science: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Indian Standards. Poultry Feeds-Specification (5th Revision) IS1374; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2007.

- Directorate General of Health Services MoHFW. National Policy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2011.

- Department of Animal Husbandry Dairying and Fisheries. National Livestock Policy; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2013.

- Bagonza, A.; Wamani, H.; Peterson, S.; Mårtensson, A.; Mutto, M.; Musoke, D.; Kitutu, F.E.; Mukanga, D.; Gibson, L.; Awor, P. Peer supervision experiences of drug sellers in a rural district in East-Central Uganda: A qualitative study. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Ebata, A.; MacGregor, H. Interventions to Reduce Antibiotic Prescribing in LMICs: A Scoping Review of Evidence from Human and Animal Health Systems. Antibiotics 2018, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durrance-Bagale, A.; Rudge, J.W.; Singh, N.B.; Belmain, S.R.; Howard, N. Drivers of zoonotic disease risk in the Indian subcontinent: A scoping review. One Health 2021, 13, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swai, E.S.; Schoonman, L.; Daborn, C.J. Knowledge and attitude towards zoonoses among animal health workers and livestock keepers in Arusha and Tanga, Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2010, 12, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2017.

- Helou, R.I.; Foudraine, D.E.; Catho, G.; Latif, A.P.; Verkaik, N.J.; Verbon, A. Use of stewardship smartphone applications by physicians and prescribing of antimicrobials in hospitals: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, D.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.K. Delivery of Animal Healthcare Services in Uttar Pradesh: Present Status, Challenges and Opportunities. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2015, 28, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The Drugs and Cosmetics Act and Rules; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2016.

- World Health Organization. WHO List of Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine (WHO CIA List); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.J. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Chander, M. Perceived constraints to private veterinary practice in India. Prev. Veter. Med. 2003, 60, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, C.G.; Larson, T.A.; Uden, D.L. Chloramphenicol-Associated Aplastic Anemia. J. Pharm. Technol. 1988, 4, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services. Report on Carcinogens Background Document for Chloramphenicol; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000.

- EU Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 on Pharmacologically Active Substances and Their Classification Regarding Maximum Residue Limits in Foodstuffs of Animal Origin; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Commerce. S.O.722 (E); Gazette of India: New Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Commerce. S.O.1442 (E). In Navigation; Gazette of India: New Delhi, India, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, S.; Yann, H.R. Antibiotic Use in Food Animals: India Overview. ReAct Asia-Pac. 2018. Available online: https://www.reactgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Antibiotic_Use_in_Food_Animals_India_LIGHT_2018_web.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Braykov, N.P.; Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Grossman, M.; Zhang, L.; Vasco, K.; Cevallos, W.; Muñoz, D.; Acevedo, A.; Moser, K.A.; Marrs, C.F.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Animal and Environmental Samples Associated with Small-Scale Poultry Farming in Northwestern Ecuador. mSphere 2016, 1, e00021-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forsberg, K.J.; Reyes, A.; Wang, B.; Selleck, E.M.; Sommer, M.O.A.; Dantas, G. The Shared Antibiotic Resistome of Soil Bacteria and Human Pathogens. Science 2012, 337, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. The 2019 WHO AWaRe Classification of Antibiotics for Evaluation and Monitoring of Use; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.C.; Keestra, S.; Tandon, P.; Chandler, C.I. WASH and Biosecurity Interventions for Reducing Burdens of Infection, Antibiotic Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in Animal Agricultural Settings: A One Health Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Lond. Sch. Hyg. Trop. Med. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04658914 (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. Farmer Field School Guidance Document; Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, A.; Jiggins, J.; Röling, N.; van den Berg, H.; Snijders, P. A Global Survey and Review of Farmer Field School Experiences. Int. Livest. Res. Inst. 2006. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/J-Jiggins/publication/228343459_A_Global_Survey_and_Review_of_Farmer_Field_School_Experiences/links/0046353bd1e61ab7f7000000/A-Global-Survey-and-Review-of-Farmer-Field-School-Experiences.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Krishi Vigyan Kendra Knowledge Network. Available online: https://kvk.icar.gov.in/ (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Prasad, M.; Joshi, S.; Joshi, G.; Bhattacharya, S.; Indrakumamr, D. Evaluation of Krishi Vigyan Kendras for Categorisation into A, B, C & D Categories; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- Hoelzer, K.; Bielke, L.; Blake, D.P.; Cox, E.; Cutting, S.M.; Devriendt, B.; Erlacher-Vindel, E.; Goossens, E.; Karaca, K.; Lemiere, S.; et al. Vaccines as alternatives to antibiotics for food producing animals. Part 1: Challenges and needs. Veter. Res. 2018, 49, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Government of India. Census of India|Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2011.

- Animal Resources Development; Animal Resources Development Department, Government of West Bengal: Kolkata, India, 2015.

- Government of India. 19th Livestock Census-2012 All India Report; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2012.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Type of Interviewee | Site 1 | Site 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Key informants (n = 9) | Private veterinarian (n = 1) 1 High school teacher (n = 2) Ex-village chief (n = 1) Homeopath (n = 1) | Veterinary officer (n = 3) 1 Private veterinarian (n = 1) 1 |

| Antibiotic providers (n = 26) | Private veterinarian (n = 1) 1 Animal Development Volunteer (n = 1) Pranibandhu (n = 1) Para-vet (n = 1) Veterinary drug shop (n = 2) Human drug shop (n = 1) Informal provider of human health (n = 5) Homeopath (n = 1) | Veterinary officer (n = 3) 1 Private veterinarian (n = 1) 1 Para-vet (n = 2) Pranibandhu (n = 1) Pranimitra (n = 1) Poultry Shop (n = 1) Human drug shop (n = 1) Informal provider of human health (n = 3) |

| Livestock keepers (n = 37) | n = 23 | n = 14 |

| Classification of Antibiotic Provider | Description of Classification |

|---|---|

| Veterinary Officer | A government employee who has received a university degree in veterinary medicine |

| Private veterinarian | A self-employed worker who has received a university degree in veterinary medicine |

| Public veterinary paraprofessional (Public VPP) 1 | A government employee who has received formal, longer term (≥six months) training from the government or recognised academic training institution in livestock services and primary veterinary care |

| Public-Private veterinary paraprofessional (Public-Private VPP) | A livestock healthcare provider who has received short term (≤six months) formal training from the government in livestock services (predominantly artificial insemination) and works in a dual public/private capacity |

| Para-vet | A self-employed animal health worker informally trained in primary veterinary care |

| Homeopath | A self-employed health worker trained in human homeopathic medicine |

| Informal provider of human health (IP) | A self-employed health worker who does not hold a medical degree but is informally trained in the practice of human medicine |

| Human drug shop 2 | A shop that sells allopathic medicines that are manufactured with the intention of human consumption |

| Veterinary drug shop | A shop that sells allopathic medicines that are manufactured with the intention of animal consumption |

| Poultry Shop | A shop that sells poultry-specific agro-veterinary supplies including allopathic veterinary medicines |

| Site 1 | Site 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical |

|

|

| Livestock Production Systems |

|

|

| Veterinary Services |

|

|

| Drug Shops |

|

|

| Antibiotic Class | Antibiotic Formulation 1 | Livestock Species |

|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | Gentamicin *,C | Cattle, Poultry, (Dogs) |

| Cephalosporin | Ceftiofur H, Ceftriaxone H, Ceftriaxone-Sulbactam H | Cattle |

| Fluroquinolone | Ciprofloxacin *,H, Enrofloxacin H, Marbofloxacin H, Norfloxacin *,H, Ofloxacin H | Goats, Poultry, Sheep |

| Macrolide | Azithromycin *,H, Tylosin H | Poultry, (Dogs) |

| Nitroimidazole | Metronidazole * | Cattle, Goats, Poultry |

| Penicillin | Amoxicillin C, Ampicillin C, Amoxicillin-Clavulanate *,C, Ampicillin-Cloxacillin C, Penicillin * | General |

| Phenicol | Chloramphenicol * | Poultry |

| Sulfonamide | Sulfadiazine * | Poultry |

| Tetracycline | Oxytetracycline *, Tetracycline *, | General |

| Trimethoprim | Trimethoprim | - 2 |

| Combination | Neomycin sulphate-Bacitracin C, Ofloxacin-Ornidazole *,H, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole * | General |

| Type of Interviewee | Interview Guide Key Topics |

|---|---|

| Key informants |

|

| Livestock keepers |

|

| Antibiotic providers |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnold, J.-C.; Day, D.; Hennessey, M.; Alarcon, P.; Gautham, M.; Samanta, I.; Mateus, A. “If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?”: A Qualitative Investigation of Antibiotic Use in Smallholder Livestock Settings in Rural West Bengal, India. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121433

Arnold J-C, Day D, Hennessey M, Alarcon P, Gautham M, Samanta I, Mateus A. “If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?”: A Qualitative Investigation of Antibiotic Use in Smallholder Livestock Settings in Rural West Bengal, India. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(12):1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121433

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnold, Jean-Christophe, Dominic Day, Mathew Hennessey, Pablo Alarcon, Meenakshi Gautham, Indranil Samanta, and Ana Mateus. 2021. "“If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?”: A Qualitative Investigation of Antibiotic Use in Smallholder Livestock Settings in Rural West Bengal, India" Antibiotics 10, no. 12: 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121433

APA StyleArnold, J.-C., Day, D., Hennessey, M., Alarcon, P., Gautham, M., Samanta, I., & Mateus, A. (2021). “If It Works in People, Why Not Animals?”: A Qualitative Investigation of Antibiotic Use in Smallholder Livestock Settings in Rural West Bengal, India. Antibiotics, 10(12), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121433