Magnetic Detection of Cancer Cells Using Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

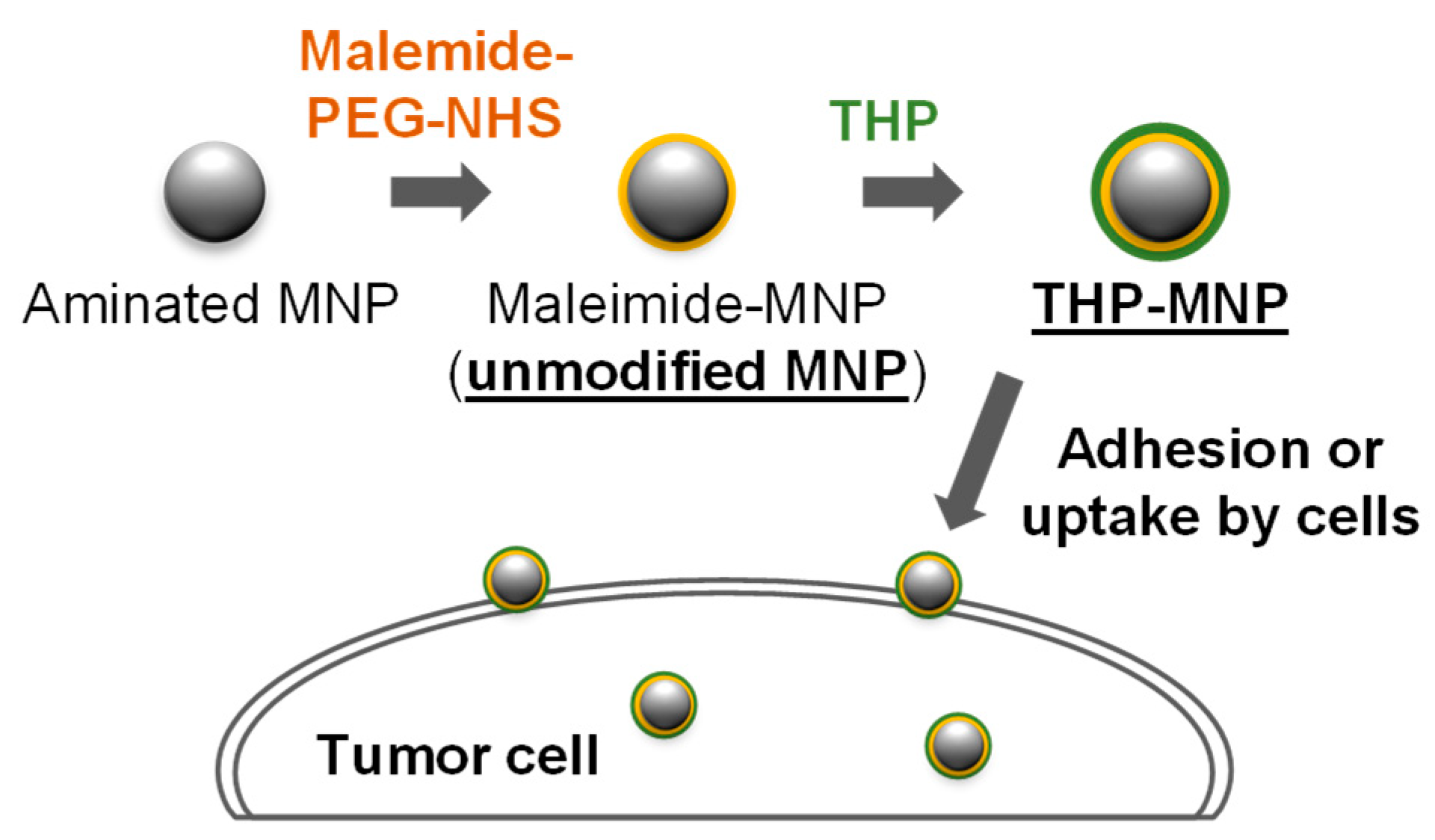

2.1. Preparation of THP-Modified MNPs

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Dark-Field Microscopy

2.4. Magnetic Measurements of THP-Modified MNPs with Cells

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Attachment and Uptake of MNPs to Cells

3.2. Magnetic Signal Intensity of THP-Modified MNPs Increased with Continuous AMF Irradiation

3.3. AMF Irradiation Decreased the Size of THP-Modified MNPs

3.4. Increase in AMF-Dependent Magnetic Signal of THP-Modified MNPs Was Inhibited in the Presence of Tumor Cells

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MNPs | Magnetic nanoparticles |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| AMF | Alternating magnetic field |

| THP | Tumor-homing peptides |

| TNC-C | C-domain of tenascin-C |

| SQUID | Superconducting quantum interference device |

References

- Rezaei, B.; Yari, P.; Sanders, S.M.; Wang, H.; Chugh, V.K.; Liang, S.; Mostufa, S.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.P.; Gómez-Pastora, J.; et al. Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Review on Synthesis, Characterization, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications. Small 2024, 20, e2304848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Kolhatkar, A.G.; Zenasni, O.; Xu, S.; Lee, T.R. Biosensing Using Magnetic Particle Detection Techniques. Sensors 2017, 17, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gu, F.; Hu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wu, C.; Deng, Y.; Gu, B.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. A Cell Wall-Targeted Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Nano-Catcher for Ultrafast Capture and SERS Detection of Invasive Fungi. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 228, 115173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.; Zhong, X.; Zang, S.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Ma, Y.; Tian, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y. Stem Cell-like Circulating Tumor Cells Identified by Pep@MNP and Their Clinical Significance in Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1327280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinari, A.; Ahmad, H.A.; Oh, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Yoon, J. Advanced Detection of Pancreatic Cancer Circulating Tumor Cells Using Biomarkers and Magnetic Particle Spectroscopy. Nanotheranostics 2025, 9, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, Q.; Liang, X.J.; Tian, J. Optimization and Design of Magnetic Ferrite Nanoparticles with Uniform Tumor Distribution for Highly Sensitive MRI/MPI Performance and Improved Magnetic Hyperthermia Therapy. Nano. Lett. 2019, 19, 3618–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Ahn, J.P.; Han, S.Y.; Lee, N.S.; Jeong, Y.G.; Kim, D.K. Highly Luminescent and Anti-Photobleaching Core-Shell Structure of Mesoporous Silica and Phosphatidylcholine Modified Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, P.; Rezaei, B.; Dey, C.; Chugh, V.K.; Veerla, N.V.R.K.; Wang, J.P.; Wu, K. Magnetic Particle Spectroscopy for Point-of-Care: A Review on Recent Advances. Sensors 2023, 23, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Park, B. Recent Advancements in Nanobioassays and Nanobiosensors for Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria Detection. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, V.D.; Wu, K.; Su, D.; Cheeran, M.C.J.; Wang, J.P.; Perez, A. Nanotechnology: Review of Concepts and Potential Application of Sensing Platforms in Food Safety. Food Microbiol. 2018, 75, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Rösch, E.L.; Viereck, T.; Schilling, M.; Ludwig, F. Toward Rapid and Sensitive Detection of SARS-CoV-2 with Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, P.; Dong, H.; Krause, H.J.; Zhang, Y.; Willbold, D.; Offenhaeusser, A.; Gu, Z. A Magnetic Nanoparticles Relaxation Sensor for Protein–Protein Interaction Detection at Ultra-Low Magnetic Field. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 80, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoguchi, T.; Kandori, A.; Kawabata, R.; Ogata, K.; Hato, T.; Tsukamoto, A.; Adachi, S.; Tanabe, K.; Tanaka, S.; Tsukada, K.; et al. Highly Sensitive Third-Harmonic Detection Method of Magnetic Nanoparticles Using an AC Susceptibility Measurement System for Liquid-Phase Assay. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 1602004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphi, N.L.; Butler, K.S.; Lovato, D.M.; Tessier, T.E.; Trujillo, J.E.; Hathaway, H.J.; Fegan, D.L.; Monson, T.C.; Stevens, T.E.; Huber, D.L.; et al. Imaging of Her2-Targeted Magnetic Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Detection: Comparison of SQUID-Detected Magnetic Relaxometry and MRI. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2012, 7, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, H.L.; Myers, W.R.; Vreeland, V.J.; Bruehl, R.; Alper, M.D.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Clarke, J. Detection of Bacteria in Suspension by Using a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Chiu, M.J.; Chen, T.F.; Horng, H.E. Detection of Plasma Biomarkers Using Immunomagnetic Reduction: A Promising Method for the Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurol. Ther. 2017, 6, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, T.; Matsumi, Y.; Aono, H.; Ohara, T.; Tazawa, H.; Shigeyasu, K.; Yano, S.; Takeda, S.; Komatsu, Y.; Hoffman, R.M.; et al. Immuno-Hyperthermia Effected by Antibody-Conjugated Nanoparticles Selectively Targets and Eradicates Individual Cancer Cells. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershina, A.G.; Brikunova, O.Y.; Demin, A.M.; Abakumov, M.A.; Vaneev, A.N.; Naumenko, V.A.; Erofeev, A.S.; Gorelkin, P.V.; Nizamov, T.R.; Muslimov, A.R.; et al. Variation in Tumor PH Affects PH-Triggered Delivery of Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2021, 32, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, G.; Fan, Z.; Ning, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Q. Optimization, Characterization and In Vivo Evaluation of Paclitaxel-Loaded Folate-Conjugated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingasamy, P.; Põšnograjeva, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Tobi, A.; Rinken, A.; General, I.J.; Asciutto, E.K.; Teesalu, T. Pl1 Peptide Engages Acidic Surfaces on Tumor-Associated Fibronectin and Tenascin Isoforms to Trigger Cellular Uptake. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingasamy, P.; Tobi, A.; Kurm, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Sudakov, A.; Salumäe, M.; Rätsep, T.; Asser, T.; Bjerkvig, R.; Teesalu, T. Tumor-Penetrating Peptide for Systemic Targeting of Tenascin-C. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tsutsumiuchi, K.; Imai, R.; Miki, Y.; Kondo, A.; Nakagawa, H.; Watanabe, K.; Ohtsuki, T. In Vitro Study of Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Molecules 2024, 29, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinno, K.; Hiramatsu, B.; Tsunashima, K.; Fujimoto, K.; Sakai, K.; Kiwa, T.; Tsukada, K. Magnetic Characterization Change by Solvents of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Liquid-Phase Magnetic Immunoassay. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 125317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Naito, K.; Wang, J.; Kasuda, S.; Kiwa, T. Coagulation Testing Method Using Magnetic Nanoparticles. Jpn. J. Appl. Phy. 2025, 64, 020902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izak-Nau, E.; Niggemann, L.P.; Göstl, R. Brownian Relaxation Shakes and Breaks Magnetic Iron Oxide-Polymer Nanocomposites to Release Cargo. Small 2024, 20, e2304527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An Enhanced Web Server for Large-Scale Expression Profiling and Interactive Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birchler, M.T.; Milisavlijevic, D.; Pfaltz, M.; Neri, D.; Odermatt, B.; Schmid, S.; Stoeckli, S.J. Expression of the Extra Domain B of Fibronectin, a Marker of Angiogenesis, in Head and Neck Tumors. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingasamy, P.; Tobi, A.; Haugas, M.; Hunt, H.; Paiste, P.; Asser, T.; Rätsep, T.; Kotamraju, V.R.; Bjerkvig, R.; Teesalu, T. Bi-Specific Tenascin-C and Fibronectin Targeted Peptide for Solid Tumor Delivery. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiss, M.; Beckmann, K.; Girós, A.; Costell, M.; Fässler, R. The Role of Integrin Binding Sites in Fibronectin Matrix Assembly In Vivo. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008, 20, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokosaki, Y.; Matsuura, N.; Higashiyama, S.; Murakami, I.; Obara, M.; Yamakido, M.; Shigeto, N.; Chen, J.; Sheppard, D. Identification of the Ligand Binding Site for the Integrin A9β1 in the Third Fibronectin Type III Repeat of Tenascin-C. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 11423–11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandori, A.; Ogata, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Takuma, N.; Tanaka, K.; Murakami, M.; Miyashita, T.; Sasaki, N.; Oka, Y. Space-Time Database for Standardization of Adult Magnetocardiogram-Making Standard MCG Parameters. PACE-Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2008, 31, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R_Core_Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Particles | AMF | Particle Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Unmodified MNPs | - | 34.9 ± 12.6 |

| PL1-MNPs | - | 41.2 ± 14.0 |

| PL3-MNPs | - | 39.4 ± 11.8 |

| Unmodified MNPs | + | 32.5 ± 10.4 |

| PL1-MNPs | + | 34.8 ± 11.3 |

| PL3-MNPs | + | 36.4 ± 12.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Furutani, Y.; Yamashita, K.; Kako, S.; Watanabe, K.; Kiwa, T.; Ohtsuki, T. Magnetic Detection of Cancer Cells Using Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles. Biosensors 2026, 16, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010045

Zhou S, Furutani Y, Yamashita K, Kako S, Watanabe K, Kiwa T, Ohtsuki T. Magnetic Detection of Cancer Cells Using Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Shengli, Yuji Furutani, Kei Yamashita, Sakuya Kako, Kazunori Watanabe, Toshihiko Kiwa, and Takashi Ohtsuki. 2026. "Magnetic Detection of Cancer Cells Using Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010045

APA StyleZhou, S., Furutani, Y., Yamashita, K., Kako, S., Watanabe, K., Kiwa, T., & Ohtsuki, T. (2026). Magnetic Detection of Cancer Cells Using Tumor-Homing Peptide-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles. Biosensors, 16(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010045