Integrated Colorimetric CRISPR/Cas12a Detection of Double-Stranded DNA on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Apparatus

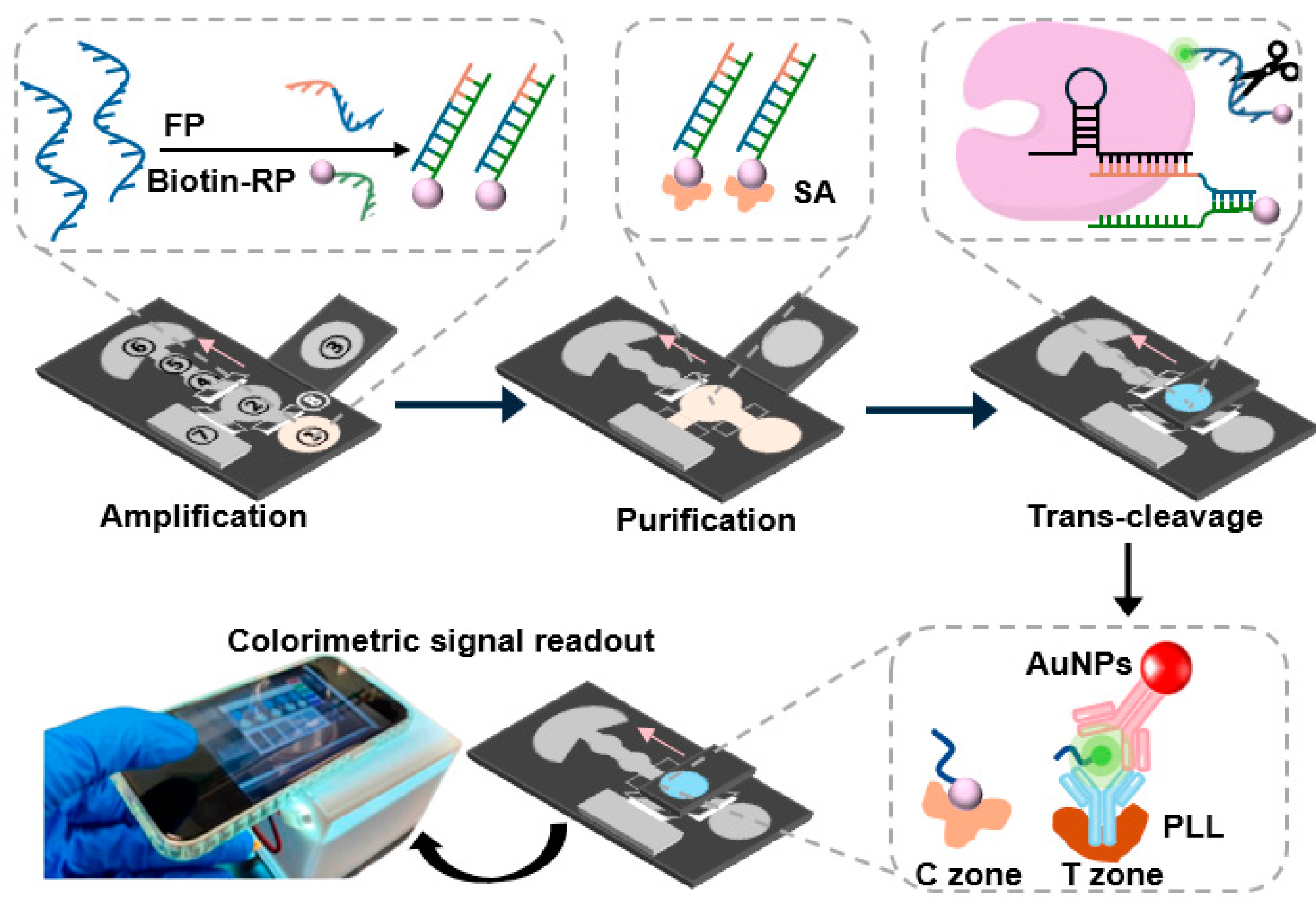

2.3. Design and Fabrication of the Colorimetric μPADs

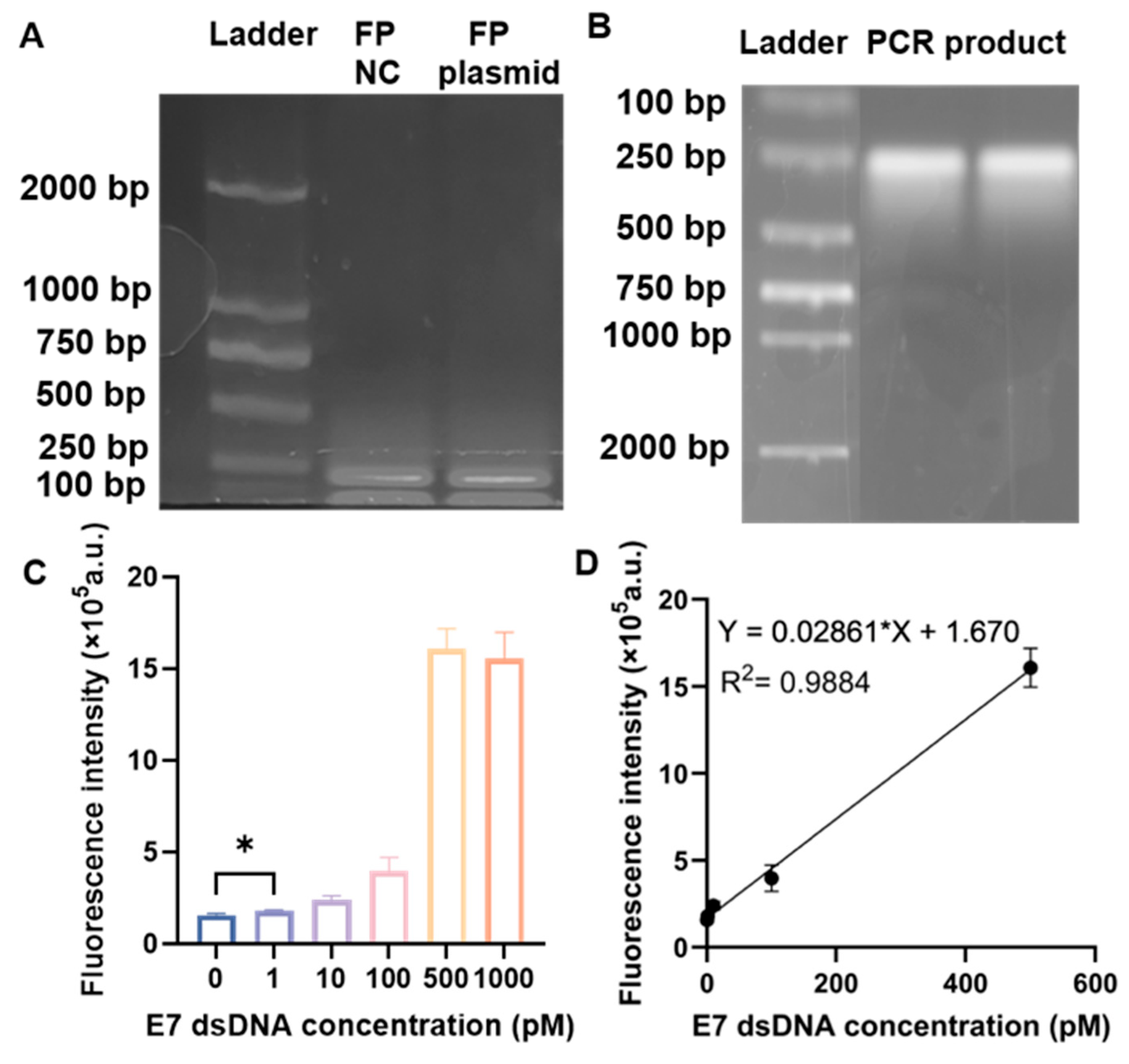

2.4. PCR Amplification and Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

2.5. RPA–CRISPR/Cas12a-Based Detection of HPV16 E7 dsDNA in Solution

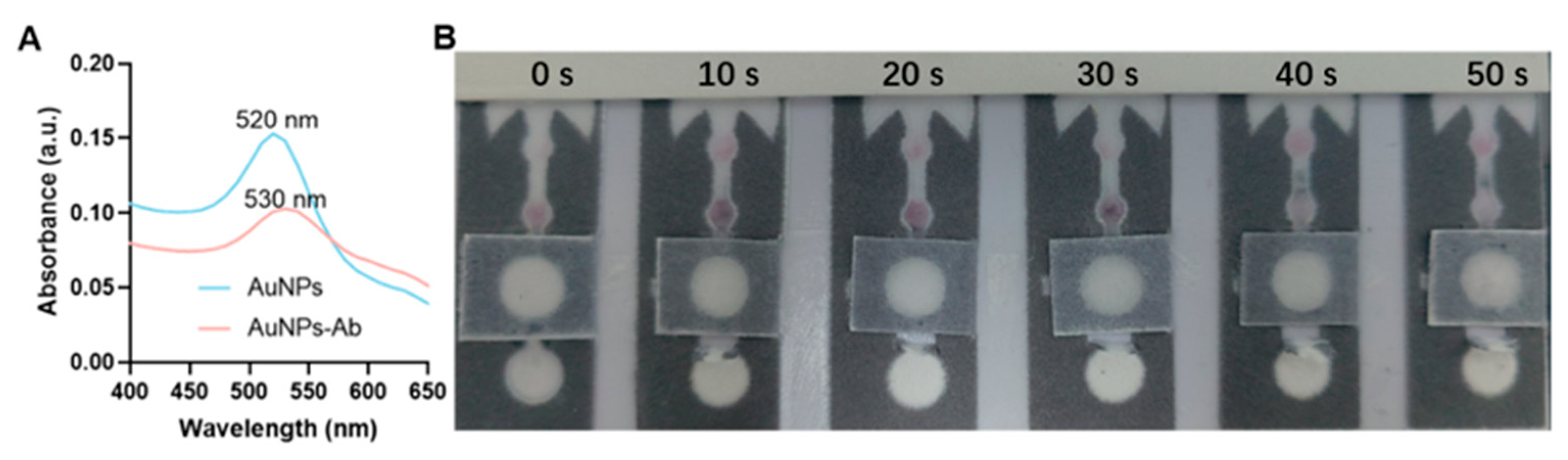

2.6. Preparation of the AuNP Probes

2.7. Detection of the Colorimetric μPADs

2.8. Detection of HPV16 E7 dsDNA on μPADs

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance of the RPA–CRISPR/Cas12a Biosensor in Solution for the Detection of HPV16 E7

3.2. AuNP-Ab Mobility Test on the μPADs

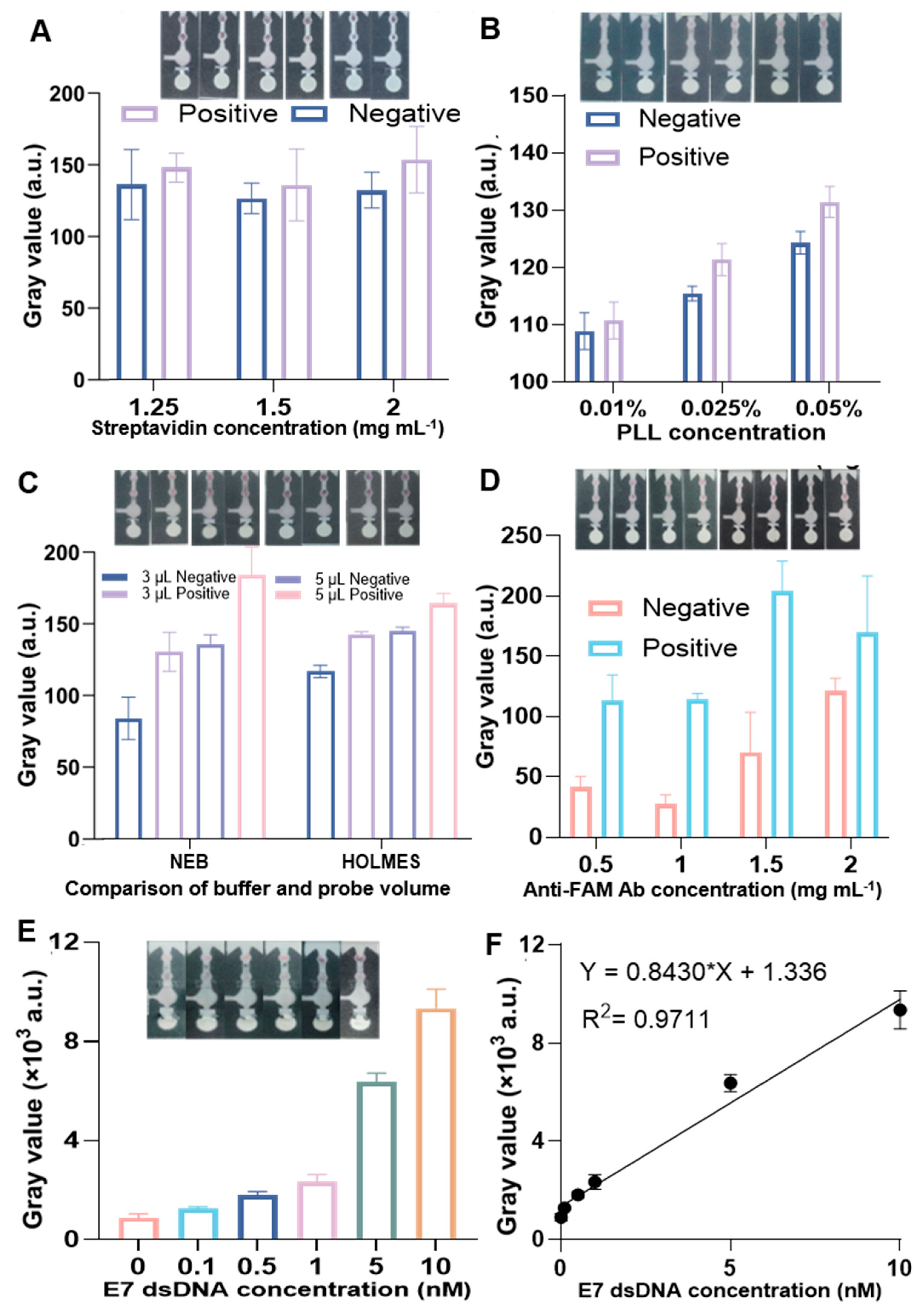

3.3. Performance of RPA–CRISPR/Cas12a Colorimetric Biosensor on µPADs for HPV16 E7 Detection

3.4. Limitations and Outlook

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Partricia, S.; Mathan, G. Overview of high-risk HPV’s 16 and 18 infected cervical cancer: Pathogenesis to prevention. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 70, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, B.; Brotons, M.; Bosch, F.X.; Bruni, L. Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 47, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Tao, S.; Shi, D.; Jiang, X.; Yu, T.; Long, Y.; Song, L.; Liu, G. Special RCA based sensitive point-of-care detection of HPV mRNA for cervical cancer screening. Aggregate 2024, 5, e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky-Avellaneda, K.D.; Laurie, C.; Tsyruk-Romano, O.; El-Zein, M.; Franco, E.L. Human Papillomavirus Detectability and Cervical Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obs. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, A.; Crawford, R.; Egawa, N.; Griffin, H.; Doorbar, J. The early detection of cervical cancer. The current and changing landscape of cervical disease detection. Cytopathology 2020, 31, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rančić, N.K.; Golubović, M.B.; Ilić, M.V.; Ignjatović, A.S.; Živadinović, R.M.; Đenić, S.N.; Momčilović, S.D.; Kocić, B.N.; Milošević, Z.G.; Otašević, S.A. Knowledge about Cervical Cancer and Awareness of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV Vaccine among Female Students from Serbia. Medicina 2020, 56, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Z.; Jensen, E.C.; Liu, C.; Waitkus, J.T.; Yuan, X.; He, Q.; Qin, P.; Du, K. Challenges and Opportunities for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats Based Molecular Biosensing. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2497–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.C., Jr.; Denny, L.; Kuhn, L.; Pollack, A.; Lorincz, A. HPV DNA testing of self-collected vaginal samples compared with cytologic screening to detect cervical cancer. JAMA 2000, 283, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, M.; Herrero, R.; Hildesheim, A.; Sherman, M.E.; Bratti, M.; Wacholder, S.; Alfaro, M.; Hutchinson, M.; Morales, J.; Greenberg, M.D.; et al. HPV DNA testing in cervical cancer screening: Results from women in a high-risk province of Costa Rica. JAMA 2000, 283, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Z. CRISPR-Cas systems: Overview, innovations and applications in human disease research and gene therapy. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2401–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Lian, K.; Yin, L.; Wang, J.; Man, S.; Liu, G.; Ma, L. SERS-based CRISPR/Cas assay on microfluidic paper analytical devices for supersensitive detection of pathogenic bacteria in foods. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 207, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Peng, L.; Yin, L.; Liu, G.; Man, S. CRISPR-Cas12a-Powered Dual-Mode Biosensor for Ultrasensitive and Cross-validating Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2920–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Zou, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, G. CRISPR/Cas12a-based immunosensors on magnetic beads for rapid cytokine detection: IL-6 as an example. Sci. Talks 2024, 10, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, M.; Luo, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, J.; Fan, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. Advancements in the synergy of isothermal amplification and CRISPR-cas technologies for pathogen detection. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1273988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Zhuang, J.; Li, J.; Xia, L.; Hu, K.; Yin, J.; Mu, Y. Digital Recombinase Polymerase Amplification, Digital Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification, and Digital CRISPR-Cas Assisted Assay: Current Status, Challenges, and Perspectives. Small 2023, 19, 2303398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hussain, M.; Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Ali, Z.; He, N.; Tang, Y. Programmable Biosensors Based on RNA-Guided CRISPR/Cas Endonuclease. Biol. Proced. Online 2022, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Gooding, J.J. CRISPR Mediated Biosensing Toward Understanding Cellular Biology and Point-of-Care Diagnosis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20754–20766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boobphahom, S.; Ly, M.N.; Soum, V.; Pyun, N.; Kwon, O.S.; Rodthongkum, N.; Shin, K. Recent Advances in Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices toward High-Throughput Screening. Molecules 2020, 25, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, J.; Liu, G. EGaIn-Modified ePADs for Simultaneous Detection of Homocysteine and C-Reactive Protein in Saliva toward Early Diagnosis of Cardiovascular Disease. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 4265–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, S.; Baeumner, A.J. Progression of Paper-Based Point-of-Care Testing toward Being an Indispensable Diagnostic Tool in Future Healthcare. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Diao, W.; Zhou, C.; Liu, G. Simultaneous binding of carboxyl and amino groups to liquid metal surface for biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 9703–9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Fan, K.; Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, D.; Liu, G. Machine-Learning-Based Colorimetric Sensor on Smartphone for Salivary Uric Acid Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 32991–33000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, T.; Song, L.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Liu, G. CRISPR/Cas on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices for Point-of-Care Screening of Cervical Cancer. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 4569–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-A.; Yeh, W.-S.; Tsai, T.-T.; Li, Y.-D.; Chen, C.-F. Three-dimensional origami paper-based device for portable immunoassay applications. Lab A Chip 2019, 19, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Proll, G.; Builes-Münden, E.; Dietzel, A.; Wagner, S.; Gauglitz, G. Tools to compare antibody gold nanoparticle conjugates for a small molecule immunoassay. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehle, K.E.; Gilliand, J.; Wheeldon, C.R.; Holder, A.; Adkins, J.A.; Geiss, B.J.; Ryan, E.P.; Henry, C.S. Utilizing Paper-Based Devices for Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6886–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; He, J.; Cui, H. High-resolution temporally resolved chemiluminescence based on double-layered 3D microfluidic paper-based device for multiplexed analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, B.; Chen, L.; Qin, W. A Three-Dimensional Origami Paper-Based Device for Potentiometric Biosensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13033–13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, N.-M.; Kalogianni, D.P.; Christopoulos, T.K. Macromolecular crowding agents enhance the sensitivity of lateral flow immunoassays. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 218, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Amount Added (nM) | Gray Value (×103 a.u.) | Amount Found | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 1.27 | 0.101 | 101 |

| 1 | 2.83 | 0.962 | 96.2 |

| 5 | 7.16 | 4.86 | 97.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Wen, T.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. Integrated Colorimetric CRISPR/Cas12a Detection of Double-Stranded DNA on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices. Biosensors 2026, 16, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010032

Zhang Z, Fu Q, Wen T, Zheng Y, Ma Y, Liu S, Liu G. Integrated Colorimetric CRISPR/Cas12a Detection of Double-Stranded DNA on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhiheng, Qiyu Fu, Tiantai Wen, Youmin Zheng, Yincong Ma, Shixian Liu, and Guozhen Liu. 2026. "Integrated Colorimetric CRISPR/Cas12a Detection of Double-Stranded DNA on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010032

APA StyleZhang, Z., Fu, Q., Wen, T., Zheng, Y., Ma, Y., Liu, S., & Liu, G. (2026). Integrated Colorimetric CRISPR/Cas12a Detection of Double-Stranded DNA on Microfluidic Paper-Based Analytical Devices. Biosensors, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010032