Detection of Premalignant Cervical Lesions via Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Construction of MAA Biosensors

2.3. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

2.4. Cell-MAA Biosensor Interactions

2.5. Neuraminidase Bioassay

2.6. Sample Collection

2.7. Spectral Analysis

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors

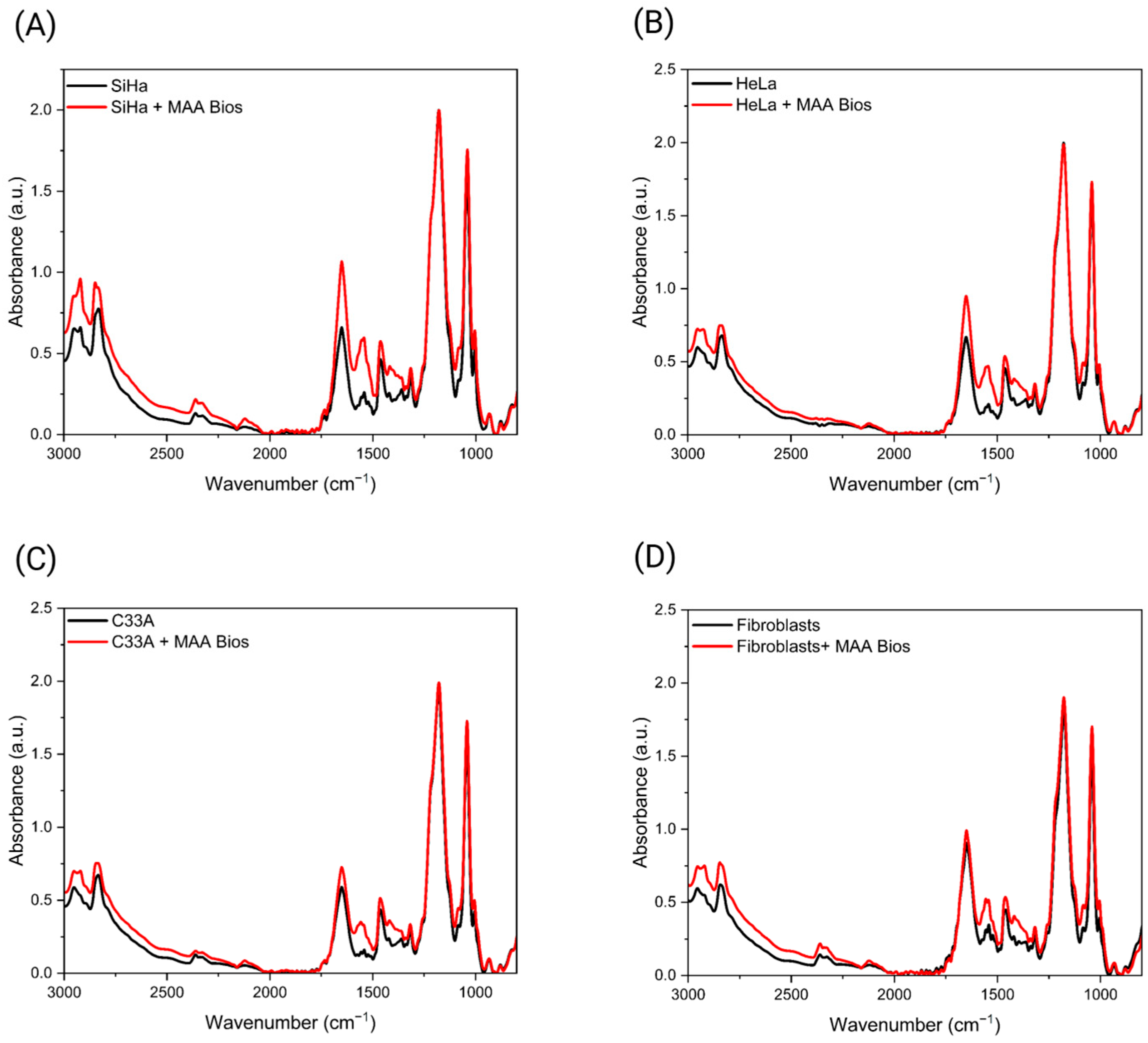

3.2. Detection of Sialic Acid Terminations in Cervical Cancer Cell Lines Using ATR-FTIR

3.3. Specificity Confirmation of MAA Biosensors via Neuraminidase Bioassay

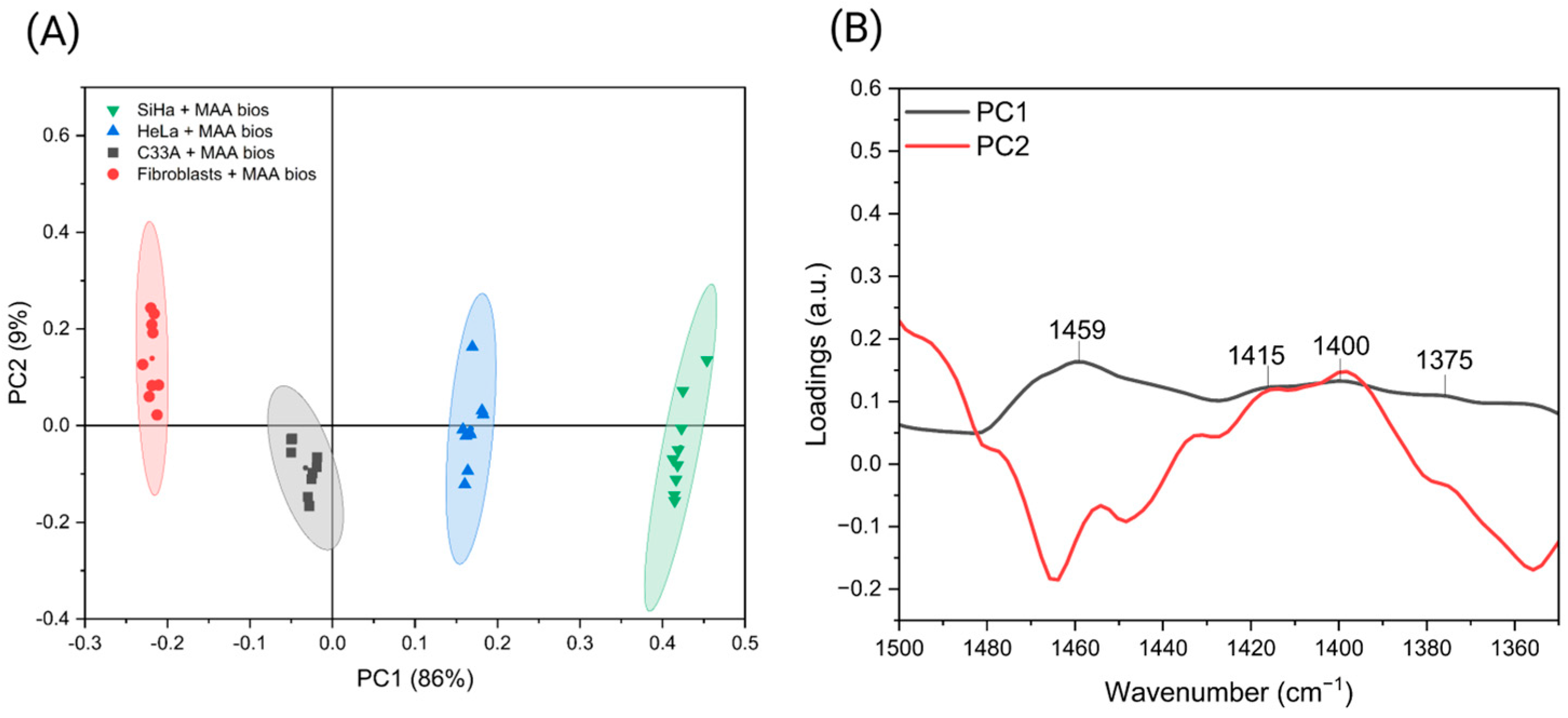

3.4. Differentiation of Premalignant Cervical Lesions Using MAA Biosensors and PCA

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vallejo-Ruiz, V.; Gutiérrez-Xicotencatl, L.; Medina-Contreras, O.; Lizano, M. Molecular Aspects of Cervical Cancer: A Pathogenesis Update. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1356581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Cao, C.; Wu, P.; Huang, X.; Ma, D. Advances in Cervical Cancer: Current Insights and Future Directions. Cancer Commun. 2025, 45, 77–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najib, F.S.; Hashemi, M.; Shiravani, Z.; Poordast, T.; Sharifi, S.; Askary, E. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cervical Pap Smear and Colposcopy in Detecting Premalignant and Malignant Lesions of Cervix. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 11, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, W.A.; Ismail, S.; Mokhtar, F.S.; Alquran, H.; Al-Issa, Y. Cervical Cancer Detection Techniques: A Chronological Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashedemi, O.; Ozoemena, O.C.; Peteni, S.; Haruna, A.B.; Shai, L.J.; Chen, A.; Rawson, F.; Cruickshank, M.E.; Grant, D.; Ola, O.; et al. Advances in Human Papillomavirus Detection for Cervical Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: Challenges of Conventional Methods and Opportunities for Emergent Tools. Anal. Methods 2024, 17, 1428–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza Ramirez, C.A.; Greenop, M.; Almoshawah, Y.A.; Martin Hirsch, P.L.; Rehman, I.U. Advancing Cervical Cancer Diagnosis and Screening with Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 23, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.; Macauley, M.S. Hypersialylation in Cancer: Modulation of Inflammation and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, G.; Guan, F. Biological Functions and Analytical Strategies of Sialic Acids in Tumor. Cells 2020, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; He, M.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Hu, B. Boronic Acid Recognition Based-Gold Nanoparticle-Labeling Strategy for the Assay of Sialic Acid Expression on Cancer Cell Surface by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Analyst 2016, 141, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, D.; Reyes-Leyva, J.; Santos-López, G.; Zenteno, E.; Vallejo-Ruiz, V. Increased Expression of Sialic Acid in Cervical Biopsies with Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. Diagn. Pathol. 2010, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, K.; Chauke, S.; Thwala, L.; Mthunzi-Kufa, P. Aptamers and Antibodies in Optical Biosensing; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 2, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, J.; Fan, S.; Ding, S.; Ren, L. Gold Nanoparticles Based Optical Biosensors for Cancer Biomarker Proteins: A Review of the Current Practices. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 877193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari Nakhjavani, S.; Mirzajani, H.; Carrara, S.; Onbaşlı, M.C. Advances in Biosensor Technologies for Infectious Diseases Detection. TrAC—Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Cho, H.Y.; Choi, H.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.W. Application of Gold Nanoparticle to Plasmonic Biosensors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.N.L.; Nguyen, S.H.; Tran, M.T. A Comprehensive Review of Transduction Methods of Lectin-Based Biosensors in Biomedical Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloise, N.; Strada, S.; Dacarro, G.; Visai, L. Gold Nanoparticles Contact with Cancer Cell: A Brief Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.B.; Ferreira, D.; Fernandes, A.R.; Baptista, P.V. Engineering Gold Nanoparticles for Molecular Diagnostics and Biosensing. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 15, e1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumalasari, M.R.; Alfanaar, R.; Andreani, A.S. Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): A Versatile Material for Biosensor Application. Talanta Open 2024, 9, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liou, Y.L.; Kang, Y.N.; Tan, Z.R.; Peng, M.J.; Zhou, H.H. Real-Time Colorimetric Detection of DNA Methylation of the PAX1 Gene in Cervical Scrapings for Cervical Cancer Screening with Thiol-Labeled PCR Primers and Gold Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 5335–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Chica, C.E.; Alfonso Tobón, L.L.; López Abella, J.J.; Valencia Piedrahita, M.P.; Neira Acevedo, D.; Bermúdez, P.C.; Arrivillaga, M.; Jaramillo-Botero, A. Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Assays for Early and Rapid Screening of the Oncogenic HPV Variants 16 and 18. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 568, 120144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.R.; Holdcraft, C.J.; Yin, A.C.; Nicoletto, R.E.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, H.; Temiakov, D.; Goldberg, G.S. Maackia Amurensis Seed Lectin Structure and Sequence Comparison with Other M. Amurensis Lectins. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibikova, O.; Haas, J.; López-Lorente, Á.I.; Popov, A.; Kinnunen, M.; Ryabchikov, Y.; Kabashin, A.; Meglinski, I.; Mizaikoff, B. Surface Enhanced Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy Based on Gold Nanostars and Spherical Nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 990, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campu, A.; Lerouge, F.; Maniu, D.; Magyari, K.; Focsan, M. Ultrasensitive SEIRA Detection Using Gold Nanobipyramids: Toward Efficient Multimodal Immunosensor. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1246, 131160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, C.L.M.; Lima, K.M.G.; Singh, M.; Martin, F.L. Tutorial: Multivariate Classification for Vibrational Spectroscopy in Biological Samples. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2143–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitnikova, V.E.; Kotkova, M.A.; Nosenko, T.N.; Kotkova, T.N.; Martynova, D.M.; Uspenskaya, M.V. Breast Cancer Detection by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy of Blood Serum and Multivariate Data-Analysis. Talanta 2020, 214, 120857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, N.M.P.; Machado, B.H.; Koche, A.; da Silva Furtado, L.B.F.; Becker, D.; Corbellini, V.A.; Rieger, A. Discrimination of Dyslipidemia Types with ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics Associated with Multivariate Analysis of the Lipid Profile, Anthropometric, and pro-Inflammatory Biomarkers. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 540, 117231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio Cañas, R.; Jaramillo Flores, M.E.; Vallejo Ruiz, V.; Delgado Macuil, R.J.; López Gayou, V. Detection of Sialic Acid to Differentiate Cervical Cancer Cell Lines Using a Sambucus Nigra Lectin Biosensor. Biosensors 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeshaprasad, M.G.; Govindappa, P.K.; Nelson, A.M.; Elfar, J.C. Isolation, Culture, and Characterization of Primary Schwann Cells, Keratinocytes, and Fibroblasts from Human Foreskin. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 181, e63776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidondo, L.; Landeira, M.; Festari, F.; Freire, T.; Giacomini, C. A Biotechnological Tool for Glycoprotein Desialylation Based on Immobilized Neuraminidase from Clostridium Perfringens. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanayutsiri, T.; Patrojanasophon, P.; Opanasopit, P.; Ngawhirunpat, T.; Plianwong, S.; Rojanarata, T. Rapid Synthesis of Chitosan-Capped Gold Nanoparticles for Analytical Application and Facile Recovery of Gold from Laboratory Waste. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraj, F.; Alotibi, I.; Al-Zahrani, M.; Albiheyri, R.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Nass, N.M.; Abd-Ellatif, S.; Makhlof, R.T.M.; Alsaad, M.A.; Sajer, B.H.; et al. Green Synthesis of Chitosan-Capped Gold Nanoparticles Using Salvia Officinalis Extract: Biochemical Characterization and Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horo, H.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Mandal, B.; Kundu, L.M. Synthesis of Functionalized Silk-Coated Chitosan-Gold Nanoparticles and Microparticles for Target-Directed Delivery of Antitumor Agents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 258, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, H.; Salehi, R.; Pourhassan-Moghaddam, M.; Mahmoodi, S.; Poursalehi, Z.; Vasilescu, S. Antibody Conjugated Green Synthesized Chitosan-Gold Nanoparticles for Optical Biosensing. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 2019, 33, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Islam, M.; Alabbosh, K.F.; Manan, S.; Khan, S.; Ahmad, F.; Ullah, M.W. Chitosan-Based Nanostructured Biomaterials: Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C.O.; Gunasekaran, S.; Ravishankar, C.N. Chitosan-Capped Gold Nanoparticles for Indicating Temperature Abuse in Frozen Stored Products. npj Sci. Food 2019, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahatnirunkul, T.; Tomlinson, D.C.; McPherson, M.J.; Millner, P.A. One-Step Gold Nanoparticle Size-Shift Assay Using Synthetic Binding Proteins and Dynamic Light Scattering. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2022, 361, 131709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Holman, H.Y.N.; Hao, Z.; Bechtel, H.A.; Martin, M.C.; Wu, C.; Chu, S. Synchrotron Infrared Measurements of Protein Phosphorylation in Living Single PC12 Cells during Neuronal Differentiation. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4118–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjabi, K.; Adhikary, R.R.; Patnaik, A.; Bendale, P.; Saxena, S.; Banerjee, R. Lectin-Functionalized Chitosan Nanoparticle-Based Biosensor for Point-of-Care Detection of Bacterial Infections. Bioconjug. Chem. 2022, 33, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, F. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Esophageal Cancer by FTIR Spectroscopy of Serum and Plasma. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Duan, X.; Bin, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, Q.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y. Evaluation of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy with Multivariate Analysis as a Novel Diagnostic Tool for Lymph Node Metastasis in Gastric Cancer. Spectrochim. Acta-Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 289, 122209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghuis, A.Y.; Pijnenborg, J.F.A.; Boltje, T.J.; Pijnenborg, J.M.A. Sialic Acids in Gynecological Cancer Development and Progression: Impact on Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-De la Cruz, L.; Martínez-Morales, P.; Morán-Cruz, I.; Milflores-Flores, L.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.; González-Ramírez, C.; Ortiz-Mateos, C.; Monterrosas-Santamaría, R.; González-Frías, C.; Rodea-Ávila, C.; et al. Expression Analysis of ST3GAL4 Transcripts in Cervical Cancer Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, B.; Akpınar, Y.; Ertaş, G.; Volkan, M. Sialic Acid-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles for Sensitive and Selective Colorimetric Determination of Serotonin. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 23832–23842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallala, J.; Jeynes, C.; Saunders, S.; Smart, N.; Lloyd, G.; Riley, L.; Salmon, D.; Stone, N. Characterization of Colorectal Mucus Using Infrared Spectroscopy: A Potential Target for Bowel Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Lustig, M.; Jansen, J.H.M.; Garcia Villagrasa, L.; Raymakers, L.; Daamen, L.A.; Valerius, T.; van Tetering, G.; Leusen, J.H.W. Sialic Acids on Tumor Cells Modulate IgA Therapy by Neutrophils via Inhibitory Receptors Siglec-7 and Siglec-9. Cancers 2023, 15, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, D.R.; Felz, S.; Neu, T.R.; Pronk, M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Lin, Y. Sialic Acids in the Extracellular Polymeric Substances of Seawater-Adapted Aerobic Granular Sludge. Water Res. 2019, 155, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Rani, S.; Kumar, V.; Nakhate, K.T.; Ajazuddin; Gupta, U. Sialic Acid Conjugated Chitosan Nanoparticles: Modulation to Target Tumour Cells and Therapeutic Opportunities. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purandare, N.C.; Patel, I.I.; Trevisan, J.; Bolger, N.; Kelehan, R.; Von Bünau, G.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Prendiville, W.J.; Martin, F.L. Biospectroscopy Insights into the Multi-Stage Process of Cervical Cancer Development: Probing for Spectral Biomarkers in Cytology to Distinguish Grades. Analyst 2013, 138, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Key Spectral Bands (cm−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sialic acid—Nallala [44] | 1530 | 1438 | 1376 | |||

| Sialic acid—Rana [47] | 1528 | 1431 | 1374 | |||

| Sialic Acid | 1558 | 1544 | 1433 | 1421 | 1396 | 1375 |

| Cell culture differentiation | 1459 | 1415 | 1400 | |||

| Neuraminidase bioassay | 1553 | 1455 | 1402 | |||

| Cervical Scrapes bioassay | 1540 | 1440 | 1397 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zamudio Cañas, R.; Vallejo Ruiz, V.; Jaramillo Flores, M.E.; Delgado Macuil, R.J.; López Gayou, V. Detection of Premalignant Cervical Lesions via Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors. Biosensors 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010024

Zamudio Cañas R, Vallejo Ruiz V, Jaramillo Flores ME, Delgado Macuil RJ, López Gayou V. Detection of Premalignant Cervical Lesions via Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleZamudio Cañas, Ricardo, Verónica Vallejo Ruiz, María Eugenia Jaramillo Flores, Raúl Jacobo Delgado Macuil, and Valentín López Gayou. 2026. "Detection of Premalignant Cervical Lesions via Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010024

APA StyleZamudio Cañas, R., Vallejo Ruiz, V., Jaramillo Flores, M. E., Delgado Macuil, R. J., & López Gayou, V. (2026). Detection of Premalignant Cervical Lesions via Maackia amurensis Lectin-Based Biosensors. Biosensors, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010024