Comprehensive Review on DNA Hydrogels and DNA Origami-Enabled Wearable and Implantable Biosensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. DNA Hydrogels as Adaptive Transduction Media

2.1. DNA Hydrogels Fabrication Strategies and Structural Features

2.1.1. Pure DNA Hydrogels

2.1.2. Hybrid DNA Hydrogels

2.2. Stimuli-Responsive Designs of DNA Hydrogels

2.3. DNA Hydrogel-Based Wearable Biosensors

2.4. Performance Comparison of DNA-Based Wearable and Implantable Biosensors

3. DNA Origami Nanotechnology

3.1. Two-Dimensional DNA Origami

3.1.1. Two-Dimensional DNA Origami Design, Synthesis

3.1.2. Two-Dimensional DNA Origami-Based Biosensor Strategies and Effect Mechanism

3.2. Three-Dimensional DNA Origami

3.2.1. Three-Dimensional DNA Origami Design, Synthesis

3.2.2. Three-Dimensional DNA Origami-Based Biosensor Strategies and Effect Mechanism

3.3. Applications of DNA Origami in Biosensors

3.3.1. Protein Detection

3.3.2. Nucleic Acid Detection

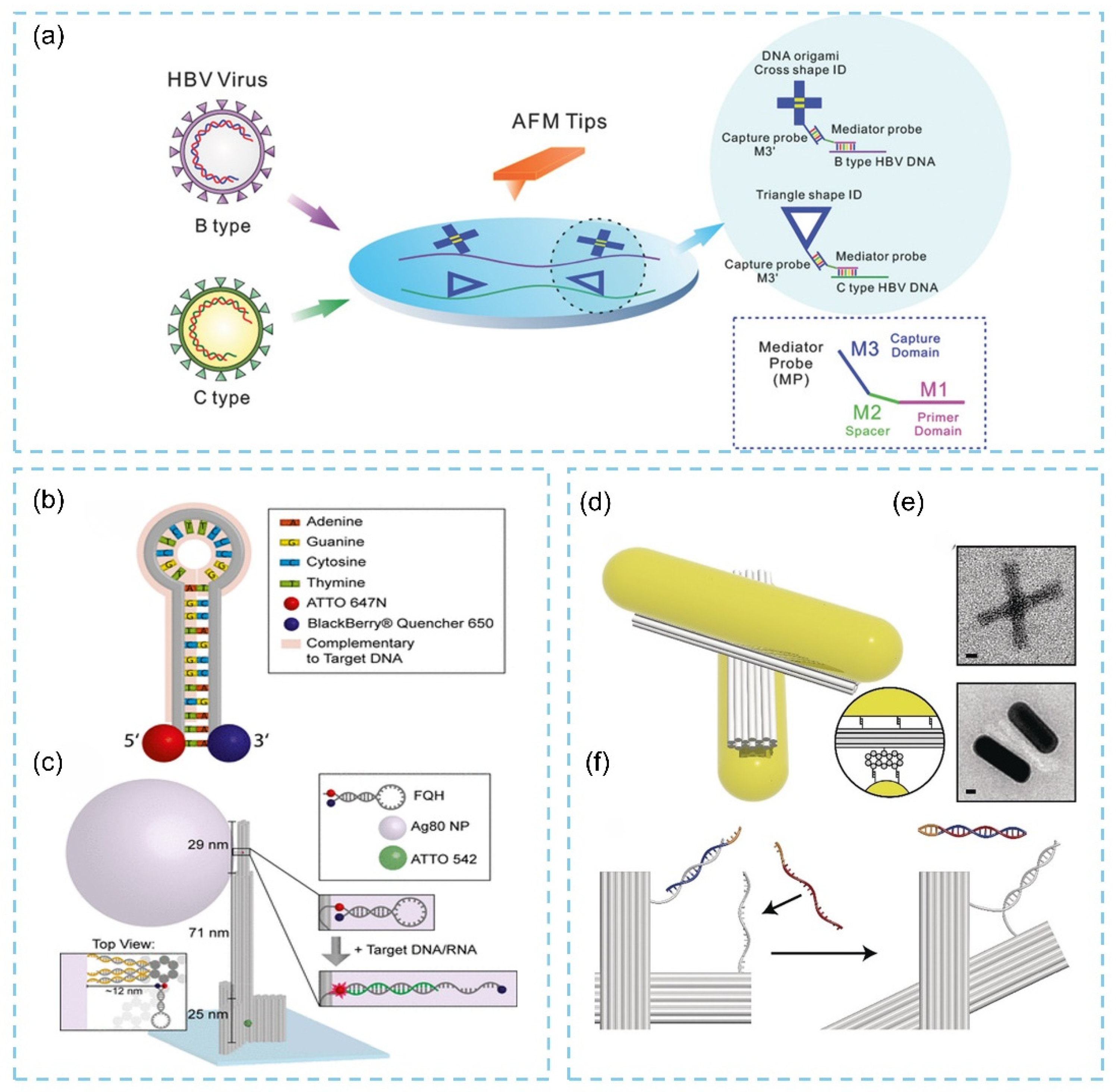

3.3.3. Virus Detection

3.4. System-Level Integration: Flexible Electronics, Microfluidics, and Wireless Readout

4. The Challenges of DNA Technology

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, Y.; Duan, X.; Huang, J. DNA Hydrogels as Functional Materials and Their Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gačanin, J.; Synatschke, C.V.; Weil, T. Biomedical Applications of DNA-Based Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1906253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Cheng, E.; Yang, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, D. Self-assembled DNA hydrogels with designable thermal and enzymatic responsiveness. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linko, V.; Eerikainen, M.; Kostiainen, M.A. A modular DNA origami-based enzyme cascade nanoreactor. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5351–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yu, L.; Huang, C.-M.; Arya, G.; Chang, S.; Ke, Y. Programmable Transformations of DNA Origami Made of Small Modular Dynamic Units. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2256–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Lin, Z.; Chen, L.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dou, Q.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, M.; Niu, L.; et al. Modular DNA-Origami-Based Nanoarrays Enhance Cell Binding Affinity through the “Lock-and-Key” Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 5447–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lyu, D.; Liu, S.; Guo, W. DNA Hydrogels and Microgels for Biosensing and Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1806538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Fan, S.; Ge, H.; Luo, T.; Tang, L.; Ji, B.; Zhang, C.; Cui, D.; Ke, Y.; et al. Modular Reconfigurable DNA Origami: From Two-Dimensional to Three-Dimensional Structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 23277–23282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Chu, M.; Chen, T.; Seung Lee, C.; Bae, J. Novel DNA-based polysulfide sieves incorporated with MOF providing excellent 3D Li+ pathway for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 614, 156163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Bae, J. DNA-Guided Li2S Nanostructure Deposition for High-Sulfur-Loaded Li–S Batteries. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 11037–11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, S.; Han, D.; Ren, S.; Qin, K.; Li, S.; Gao, Z. Stimuli-responsive DNA-based hydrogels for biosensing applications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, G.; Tian, L. A pure DNA hydrogel with stable catalytic ability produced by one-step rolling circle amplification. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3038–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretan, M.; Domljanovic, I.; Lakatos, M.; Ruegg, C.; Acuna, G.P. DNA Origami as Emerging Technology for the Engineering of Fluorescent and Plasmonic-Based Biosensors. Materials 2020, 13, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, W.; Yang, S.; Wang, R. Facile and Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensors for MicroRNA Detection Based on DNA Origami Nanostructures. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 11025–11031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Chen, S.; Fan, S.; Liu, Y.; Qi, J.; Lim, C.T. Interstitial fluid-based wearable biosensors for minimally invasive healthcare and biomedical applications. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Campbell, A.S.; de Ávila, B.E.-F.; Wang, J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.A.; Li, R.; Tse, Z.T.H. Reshaping healthcare with wearable biosensors. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.H.; Lee, J.B.; Park, N.; Kwon, S.Y.; Umbach, C.C.; Luo, D. Enzyme-catalysed assembly of DNA hydrogel. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Xue, C.; Yu, X.; Hu, S.; Luo, M.; Wu, Z.-S. Spiraling-Based Structural DNA Nanotechnology to Regulate the Orientation of Sticky Ends for Intelligent Assembly of In Vivo Targeting DNA Nanostructures. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 20937–20949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, C.; Cansiz, S.; Wu, C.; Xu, J.; Cui, C.; Liu, Y.; Hou, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Self-assembly of DNA nanohydrogels with controllable size and stimuli-responsive property for targeted gene regulation therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1412–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; Peng, S.; Yang, D.; Roh, Y.H.; Funabashi, H.; Park, N.; Rice, E.J.; Chen, L.; Long, R.; Wu, M.; et al. A mechanical metamaterial made from a DNA hydrogel. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chao, J.; Liu, H.; Su, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Willner, I.; Fan, C. Clamped Hybridization Chain Reactions for the Self-Assembly of Patterned DNA Hydrogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, T.; Zhao, B.; Yan, J. Investigation of the Impact of Hydrogen Bonding Degree in Long Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Generated with Dual Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA) on the Preparation and Performance of DNA Hydrogels. Biosensors 2023, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, X.; Bing, T.; Cao, Z.; Shangguan, D. General Peroxidase Activity of G-Quadruplex−Hemin Complexes and Its Application in Ligand Screening. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7817–7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahara, S.; Matsuda, T. Hydrogel formation via hybridization of oligonucleotides derivatized in water-soluble vinyl polymers. Polym. Gels Netw. 1996, 4, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Preparation Strategies, Functional Regulation, and Applications of Multifunctional Nanomaterials-Based DNA Hydrogels. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2301261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, K.; Wang, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yan, B. Versatile synthesis of a highly porous DNA/CNT hydrogel for the adsorption of the carcinogen PAH. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2289–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premkumar, T.; Geckeler, K.E. Graphene–DNA hybrid materials: Assembly, applications, and prospects. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lee, C.J.M.; Tan, G.S.X.; Ng, P.R.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, J.; Novoselov, K.S.; Andreeva, D.V. Ultra-Tough Graphene Oxide/DNA 2D Hydrogel with Intrinsic Sensing and Actuation Functions. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, 46, 2400518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wu, D.; Sun, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, M.; Luo, D. A PEGDA/DNA Hybrid Hydrogel for Cell-Free Protein Synthesis. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K. Programmable Self-Assembly of DNA-Protein Hybrid Hydrogel for Enzyme Encapsulation with Enhanced Biological Stability. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Krissanaprasit, A.; Miles, A.; Hsiao, L.C.; LaBean, T.H. Mechanical and Electrical Properties of DNA Hydrogel-Based Composites Containing Self-Assembled Three-Dimensional Nanocircuits. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, B.; Ma, C.; Gu, X.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Su, J.; et al. Injectable and NIR-Responsive DNA-Inorganic Hybrid Hydrogels with Outstanding Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2004460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lee, H. Anti-Biofouling Strategies for Long-Term Continuous Use of Implantable Biosensors. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, S.; Lu, H.; Ying, J.Y. Acid-Resistant and Physiological pH-Responsive DNA Hydrogel Composed of A-Motif and i-Motif toward Oral Insulin Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 5461–5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Chen, T.; Song, Y.; Feng, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X. mRNA Delivery by a pH-Responsive DNA Nano-Hydrogel. Small 2021, 17, 2101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Xiang, L.; Wang, L.; Gong, H.; Chen, F.; Cai, C. pH-responsive DNA hydrogels with ratiometric fluorescence for accurate detection of miRNA-21. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1207, 339795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, R.; Mei, Z.; Hou, Y. Metalloptosis: Metal ions-induced programmed cell death based on nanomaterials for cancer therapy. Med Mat 2024, 1, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Leung, H.M.; Lo, P.K. Stimuli-Responsive Self-Assembled DNA Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Small 2017, 13, 1602881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, F.; Zhang, K.; Min, T.; Chen, D.; Wen, Y. Distance-Based Biosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Uracil-DNA Glycosylase Using Membrane Filtration of DNA Hydrogel. ACS Sensors 2021, 6, 2395–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Chen, P.; Yan, S.; Yuan, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Dou, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. Ultrasensitive Nanopore Sensing of Mucin 1 and Circulating Tumor Cells in Whole Blood of Breast Cancer Patients by Analyte-Triggered Triplex-DNA Release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21030–21039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.-C.; Willner, I. Synthesis and Applications of Stimuli-Responsive DNA-Based Nano- and Micro-Sized Capsules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Lin, X.; Waheed, A.; Ravikumar, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Chen, C. A Self-Assembled G-Quadruplex/Hemin DNAzyme-Driven DNA Walker Strategy for Sensitive and Rapid Detection of Lead Ions Based on Rolling Circle Amplification. Biosensors 2023, 13, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Lin, H.; Zhu, X.; Lou, Y.; Zheng, L. CRISPR-Responsive RCA-Based DNA Hydrogel Biosensing Platform with Customizable Signal Output for Rapid and Sensitive Nucleic Acid Detection. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 15998–16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Achavananthadith, S.; Lian, S.; Madden, L.E.; Ong, Z.X.; Chua, W.; Kalidasan, V.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Singh, P.; et al. A wireless and battery-free wound infection sensor based on DNA hydrogel. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Mao, X.; Abulaiti, M.A.; Wang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Ding, Y.; Zhai, S.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Non-Invasive Detection of Interferon-Gamma in Sweat Using a Wearable DNA Hydrogel-Based Electrochemical Sensor. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Zhang, T.; Lv, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G. His-Mediated Reversible Self-Assembly of Ferritin Nanocages through Two Different Switches for Encapsulation of Cargo Molecules. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 17080–17090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrault, S.D.; Shih, W.M. Virus-Inspired Membrane Encapsulation of DNA Nanostructures To Achieve In Vivo Stability. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5132–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Wei, W.; Yang, F.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Microneedle Array Encapsulated with Programmed DNA Hydrogels for Rapidly Sampling and Sensitively Sensing of Specific MicroRNA in Dermal Interstitial Fluid. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18366–18375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wu, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Dai, B.; Yang, C.; Liu, A.; Tang, J.; Gong, L. Design of a DNA-Based Double Network Hydrogel for Electronic Skin Applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2200066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, G. DNA-inspired anti-freezing wet-adhesion and tough hydrogel for sweaty skin sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, S.; Takahashi, N.; Miyazaki, H.; Kono, S.; Saito, K.; Kuzuya, A. DNA Origami-Based Luminescent Biosensors Enabling Smartphone Detection of Nucleic Acid Sequences. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 43300–43308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Meng, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Deng, J.; Fan, T.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Huang, H.; Li, S.; et al. Ultrasensitive DNA Origami Plasmon Sensor for Accurate Detection in Circulating Tumor DNAs. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Natarajan, A.K.; Nguyen, V.H.; Kuzyk, A. A DNA Origami-Based Chiral Plasmonic Sensing Device. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 44221–44225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothemund, P.W. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 2006, 440, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickels, P.C.; Ke, Y.; Jungmann, R.; Smith, D.M.; Leichsenring, M.; Shih, W.M.; Liedl, T.; Hogberg, B. DNA origami structures directly assembled from intact bacteriophages. Small 2014, 10, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-Y.; Lee, J.; Ahn, D.J.; Lee, S.; Oh, M.-K. Optimizing protein V untranslated region sequence in M13 phage for increased production of single-stranded DNA for origami. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6596–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Fan, C.; Gothelf, K.V.; Li, J.; Lin, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, N.; Nijenhuis, M.A.D.; Saccà, B.; Simmel, F.C.; et al. DNA origami. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodori, L.; Shahrokhtash, A.; Sørensen, E.A.; Zhang, X.; Malle, M.G.; Sutherland, D.S.; Kjems, J. Nanoscale Precise Stamping of Biomolecule Patterns Using DNA Origami. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 36931–36942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, I.; Karimian, T.; Gordiyenko, K.; Angelin, A.; Kumar, R.; Hirtz, M.; Mikut, R.; Reischl, M.; Stegmaier, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Surface-Patterned DNA Origami Rulers Reveal Nanoscale Distance Dependency of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Activation. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.M.; Kim, K.N.; Kim, J.Y.; Shin, D.O.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lieberman, M.; Kim, S.O. DNA origami nanopatterning on chemically modified graphene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 912–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissaoui, N.; Moth-Poulsen, K.; Kall, M.; Johansson, P.; Wilhelmsson, L.M.; Albinsson, B. FRET enhancement close to gold nanoparticles positioned in DNA origami constructs. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, C.; Frank, K.; Amenitsch, H.; Fischer, S.; Liedl, T.; Nickel, B. Position Accuracy of Gold Nanoparticles on DNA Origami Structures Studied with Small-Angle X-ray Scattering. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.H.; Xing, H.; Lu, Y. DNA as a Powerful Tool for Morphology Control, Spatial Positioning, and Dynamic Assembly of Nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, E.; Marini, M.; Palmano, S.; Piantanida, L.; Polano, C.; Scarpellini, A.; Lazzarino, M.; Firrao, G. A DNA Origami Nanorobot Controlled by Nucleic Acid Hybridization. Small 2014, 10, 2918–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siti, W.; Too, H.L.; Anderson, T.; Liu, X.R.; Loh, I.Y.; Wang, Z. Autonomous DNA molecular motor tailor-designed to navigate DNA origami surface for fast complex motion and advanced nanorobotics. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q.; Arai, T. Recent Progress of Magnetically Actuated DNA Micro/Nanorobots. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2022, 2022, 9758460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.-G.; Ding, B. Rationally Designed DNA-Origami Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery In Vivo. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Li, N.; Dai, L.; Liu, Q.; Song, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, J.; Ding, B.; et al. DNA Origami as an In Vivo Drug Delivery Vehicle for Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6633–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiden, J.; Bastings, M.M.C. DNA origami nanostructures for controlled therapeutic drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 52, 101411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Czajkowsky, D.M.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J.; Ye, M.; Zeng, D.; Zhou, X.; Hu, J.; Shao, Z.; Li, B.; et al. Molecular Threading and Tunable Molecular Recognition on DNA Origami Nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12172–12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Rothemund, P.W.K. Programmable molecular recognition based on the geometry of DNA nanostructures. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, A.; Endo, M.; Sugiyama, H. Single-Molecule Analysis Using DNA Origami. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.A.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y. Recent Advances of DNA Origami Technology and Its Application in Nanomaterial Preparation. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2200376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Jing, X.; Pan, M.; Liu, P.; Li, W.; Zhu, B.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Complex silica composite nanomaterials templated with DNA origami. Nature 2018, 559, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, A.N.; Saaem, I.; Tian, J.; LaBean, T.H. One-Pot Assembly of a Hetero-dimeric DNA Origami from Chip-Derived Staples and Double-Stranded Scaffold. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.; Wang, X.; Bricker, W.P.; Bathe, M. Automated sequence design of 2D wireframe DNA origami with honeycomb edges. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.; Zhang, F.; Shepherd, T.; Ratanalert, S.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Bathe, M. Autonomously designed free-form 2D DNA origami. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav0655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulais, É.; Sawaya, N.P.D.; Veneziano, R.; Andreoni, A.; Banal, J.L.; Kondo, T.; Mandal, S.; Lin, S.; Schlau-Cohen, G.S.; Woodbury, N.W.; et al. Programmed coherent coupling in a synthetic DNA-based excitonic circuit. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinath, A.; Miyazono, E.; Faraon, A.; Rothemund, P.W.K. Engineering and mapping nanocavity emission via precision placement of DNA origami. Nature 2016, 535, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogheiseh, M.; Ghasemi, R.H. Wireframe DNA origami nanostructure with the controlled opening of edges. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2025, 10, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamhoff, E.C.; Banal, J.L.; Bricker, W.P.; Shepherd, T.R.; Parsons, M.F.; Veneziano, R.; Stone, M.B.; Jun, H.; Wang, X.; Bathe, M. Programming Structured DNA Assemblies to Probe Biophysical Processes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 48, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jun, H.; Bathe, M. Programming 2D Supramolecular Assemblies with Wireframe DNA Origami. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 4403–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Jun, H.; John, T.; Zhang, K.; Fowler, H.; Doye, J.P.K.; Chiu, W.; Bathe, M. Planar 2D wireframe DNA origami. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn0039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glembockyte, V.; Grabenhorst, L.; Trofymchuk, K.; Tinnefeld, P. DNA Origami Nanoantennas for Fluorescence Enhancement. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3338–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, A.N.; Kahn, J.S.; McKeen, D.; Minevich, B.; Redeker, D.C.; Gang, O. Revealing and Engineering Assembly Pathways of 3D DNA Origami Crystals. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 37669–37678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H.; Wang, X.; Parsons, M.F.; Bricker, W.P.; John, T.; Li, S.; Jackson, S.; Chiu, W.; Bathe, M. Rapid prototyping of arbitrary 2D and 3D wireframe DNA origami. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 10265–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Pradeep Narayanan, R.; Prasad, A.; Zhang, F.; Williams, D.; Schreck, J.S.; Yan, H.; Reif, J. Automated design of 3D DNA origami with non-rasterized 2D curvature. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eade4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joty, K.; Ghimire, M.L.; Kahn, J.S.; Lee, S.; Alexandrakis, G.; Kim, M.J. DNA Origami Incorporated into Solid-State Nanopores Enables Enhanced Sensitivity for Precise Analysis of Protein Translocations. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 17496–17505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Tian, X.; Chen, Z.; Ge, Y.; Chen, C.; Gao, H.; Liu, Z.; Tung, J.; Fixler, D.; Wei, S.; et al. Ultrasensitive optoelectronic biosensor arrays based on twisted bilayer graphene superlattice. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daems, D.; Pfeifer, W.; Rutten, I.; Sacca, B.; Spasic, D.; Lammertyn, J. Three-Dimensional DNA Origami as Programmable Anchoring Points for Bioreceptors in Fiber Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23539–23547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ji, C.; Lu, X.; Cao, H.; Ling, Y.; Wu, Y.; Qian, L.; He, Y.; Song, B.; Wang, H. DNA Origami Plasmonic Nanoantenna for Programmable Biosensing of Multiple Cytokines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 9684–9692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.J.; Guareschi, M.M.; Stewart, J.M.; Wu, E.; Gopinath, A.; Arroyo-Curras, N.; Dauphin-Ducharme, P.; Plaxco, K.W.; Lukeman, P.S.; Rothemund, P.W.K. Modular DNA origami-based electrochemical detection of DNA and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2311279121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Trofymchuk, K.; Ranallo, S.; Ricci, F.; Steiner, F.; Cole, F.; Glembockyte, V.; Tinnefeld, P. Single antibody detection in a DNA origami nanoantenna. iScience 2021, 24, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, P.; Piskunen, P.; Ijäs, H.; Butterworth, A.; Linko, V.; Corrigan, D.K. Signal Amplification in Electrochemical DNA Biosensors Using Target-Capturing DNA Origami Tiles. ACS Sensors 2023, 8, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnihhin, D.; Sparvath, S.M.; Preus, S.; Birkedal, V.; Andersen, E.S. Multifluorophore DNA Origami Beacon as a Biosensing Platform. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5699–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Vietz, C.; Schroder, T.; Acuna, G.; Lalkens, B.; Tinnefeld, P. A DNA Walker as a Fluorescence Signal Amplifier. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 5368–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Pan, D.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chao, J.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Fan, C.; Shi, Y. Identifying the Genotypes of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) with DNA Origami Label. Small 2018, 14, 1701718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochmann, S.E.; Vietz, C.; Trofymchuk, K.; Acuna, G.P.; Lalkens, B.; Tinnefeld, P. Optical Nanoantenna for Single Molecule-Based Detection of Zika Virus Nucleic Acids without Molecular Multiplication. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 13000–13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funck, T.; Nicoli, F.; Kuzyk, A.; Liedl, T. Sensing Picomolar Concentrations of RNA Using Switchable Plasmonic Chirality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 13495–13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Marvi, P.K.; Ganguly, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, B.; Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Rosenkranz, A. MXene-Based Elastomer Mimetic Stretchable Sensors: Design, Properties, and Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Mao, D.; Chen, T.; Jalalah, M.; Al-Assiri, M.S.; Harraz, F.A.; Zhu, X.; Li, G. DNA Hydrogel-Based Three-Dimensional Electron Transporter and Its Application in Electrochemical Biosensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36851–36859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Tang, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Xiao, M.; Man, T.; Qu, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. Self-Assembly of Enzyme-Like Nanofibrous G-Molecular Hydrogel for Printed Flexible Electrochemical Sensors. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Yan, Q.; Zhu, Y. Mechanical properties modulation and biological applications of DNA hydrogels. Adv. Sens. Energy Mater. 2024, 3, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Arunkumar, A.; Chollangi, S.; Tan, Z.G.; Borys, M.; Li, Z.J. Clarification technologies for monoclonal antibody manufacturing processes: Current state and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Rigo, B.; Wong, G.; Lee, Y.J.; Yeo, W.-H. Advances in Wireless, Batteryless, Implantable Electronics for Real-Time, Continuous Physiological Monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Xie, Y.; Song, J. DNA Hydrogels in the Perspective of Mechanical Properties. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, e2200281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulahoum, H.; Ghorbanizamani, F. The LOD paradox: When lower isn’t always better in biosensor research and development. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 264, 116670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzumcu, A.T.; Guney, O.; Okay, O. Nanocomposite DNA hydrogels with temperature sensitivity. Polymer 2016, 100, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Okay, O. Rheological Behavior of Responsive DNA Hydrogels. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 8847–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Feng, C. How to Construct DNA Hydrogels for Environmental Applications: Advanced Water Treatment and Environmental Analysis. Small 2018, 14, 1703305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensor Type | Target Analyte | Material Platform | LOD | Response Time | Specificity | Stability (In Vivo/Ex Vivo) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable DNA hydrogel-based electrochemical sensor | IFN-γ in sweat | Aptamer–DNA hydrogel on SPCE | 0.1–1 pg/mL | <10 min | High; aptamer-specific displacement, minimal cross-reactivity | Stable during 2–4 h of continuous sweat exposure | [46] |

| DNA hydrogel–microneedle patch | microRNA in ISF | MeHA/DNA hybrid hydrogel | ~10 fM | 5–15 min | High; strand-displacement discrimination between single-base variants | Maintains mechanical integrity during 24 h skin penetration | [49] |

| Wearable infection-monitoring DNA gel | Bacterial DNase | DNase-responsive DNA hydrogel | Qualitative (visual RF shift) | Seconds–minutes | High; DNase-triggered degradation only | Stable on skin for >48 h; tolerates mechanical bending | [45] |

| DNA origami luminescent nanosensor | Viral RNA | Two-dimensional DNA origami + split luciferase | ~100 fM | <5 min | Extremely high; sequence-level precision | Stable for hours at physiological ionic strength | [52] |

| DNA origami SPR biosensor | ctDNA (point mutations) | DNA origami + AuNP SPR interface | 1–10 fM | <10 min | Single-nucleotide discrimination | Stable over 12 h continuous flow | [53] |

| DNA origami chiral plasmonic nanosensor | Viral RNA/miRNA | Reconfigurable AuNR–DNA origami | ~100 pM | Seconds | Sequence-specific switching | Stable after repeated optical cycling | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Bae, J. Comprehensive Review on DNA Hydrogels and DNA Origami-Enabled Wearable and Implantable Biosensors. Biosensors 2025, 15, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120819

Li M, Bae J. Comprehensive Review on DNA Hydrogels and DNA Origami-Enabled Wearable and Implantable Biosensors. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120819

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Man, and Joonho Bae. 2025. "Comprehensive Review on DNA Hydrogels and DNA Origami-Enabled Wearable and Implantable Biosensors" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120819

APA StyleLi, M., & Bae, J. (2025). Comprehensive Review on DNA Hydrogels and DNA Origami-Enabled Wearable and Implantable Biosensors. Biosensors, 15(12), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120819