Transparent PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Leaf Tattoos for Multiplexed Plant Health Monitoring and Energy Harvesting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of Printed Sensors onto Tomato Leaves

2.3. Characterisation of Printed Electrodes

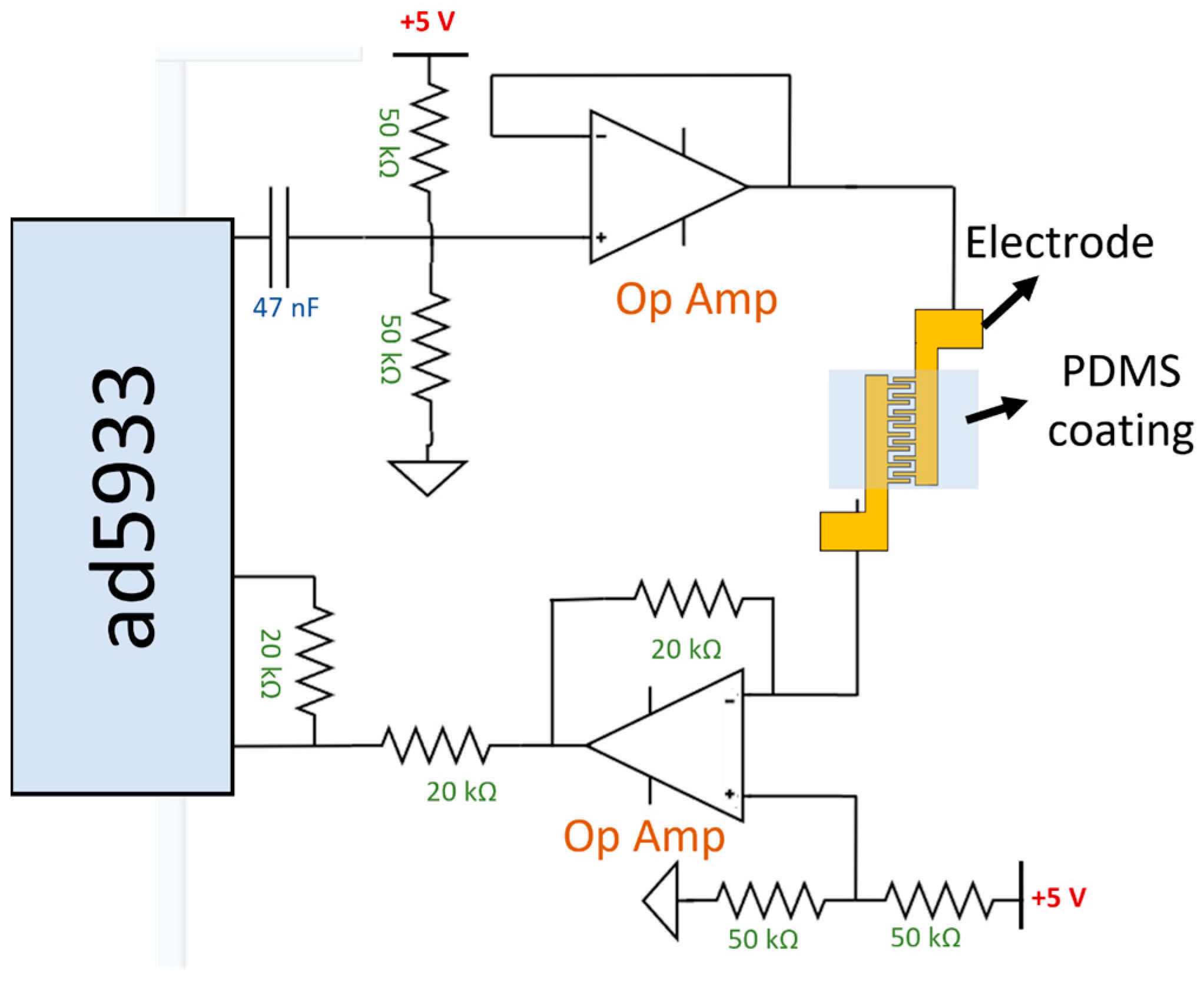

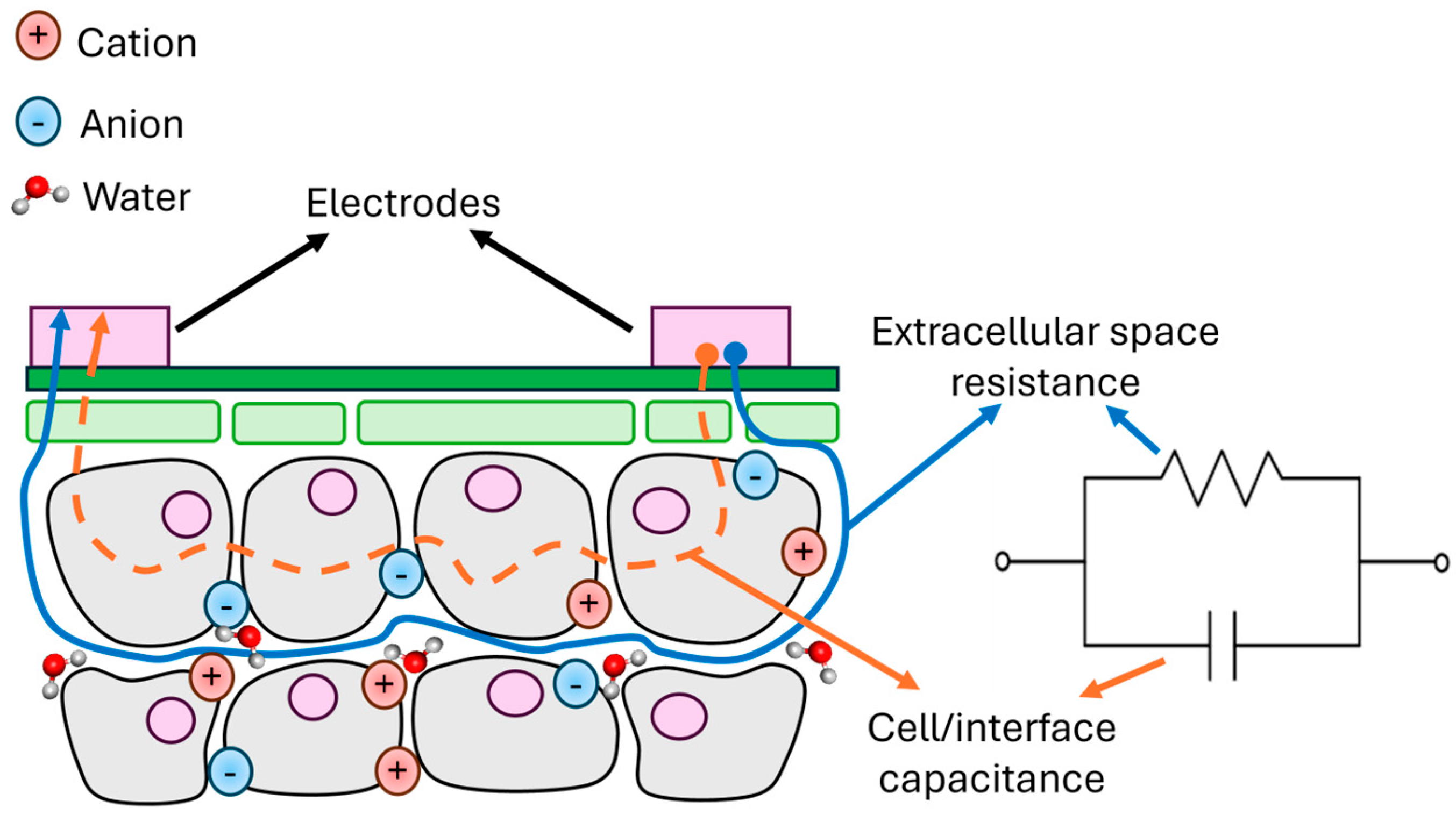

2.4. Assembly of Sensing Device and Data Analysis of Impedance

2.5. Calibration of Sensing Device in Plants

2.6. In Vivo Testing of Electrodes Directly Fabricated onto Leaves

3. Results and Discussion

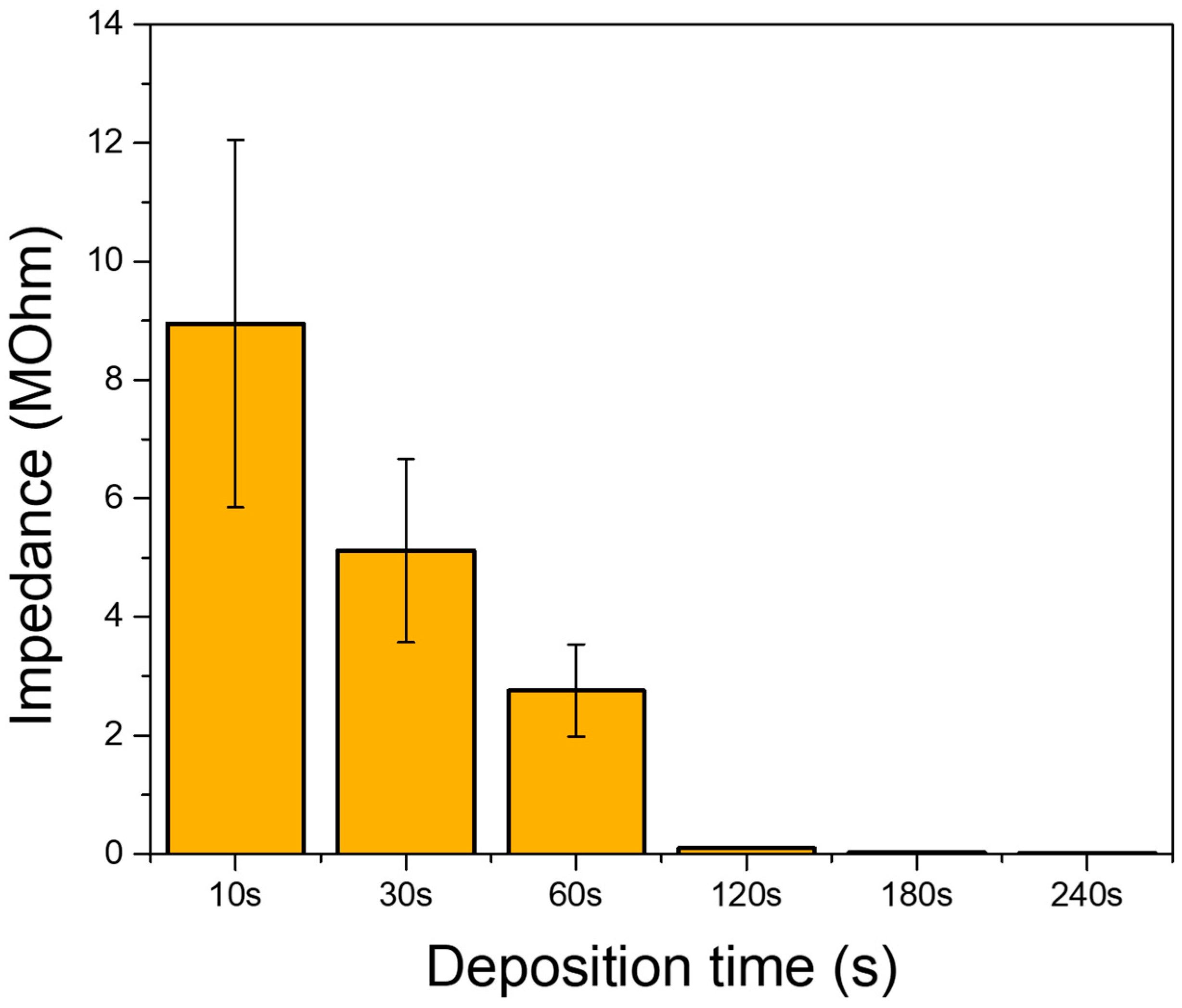

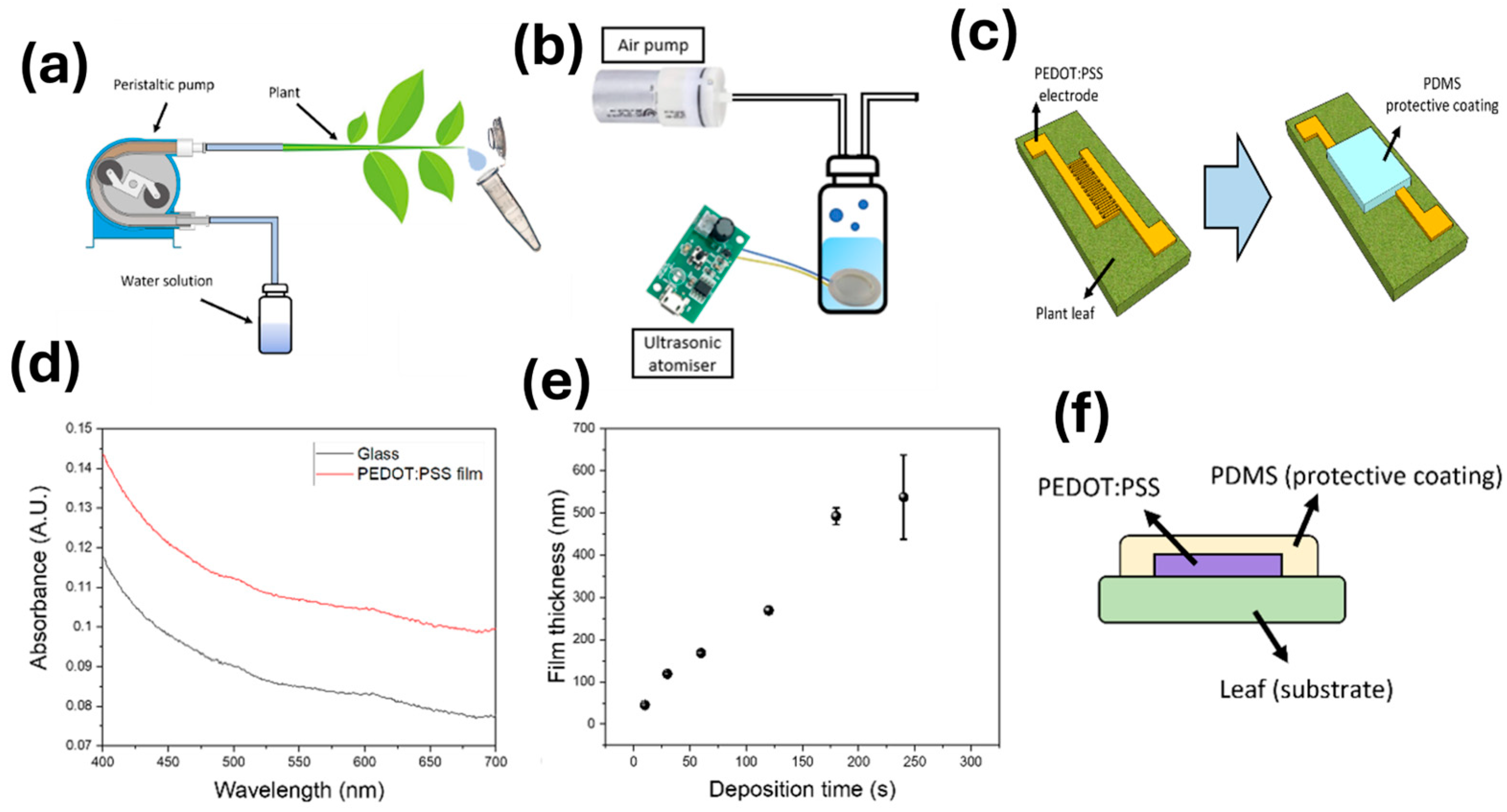

3.1. Leaf Sensor Fabrication

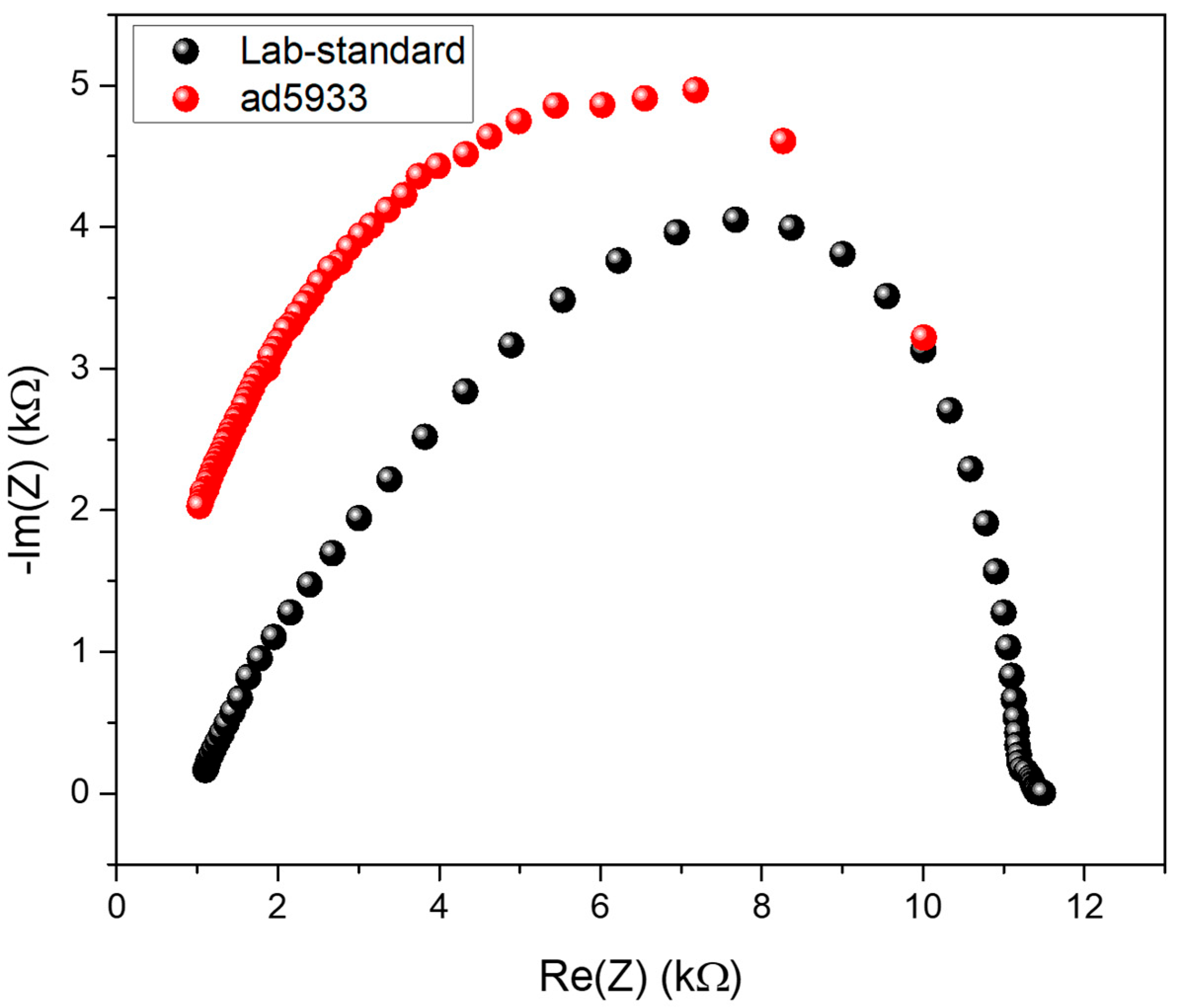

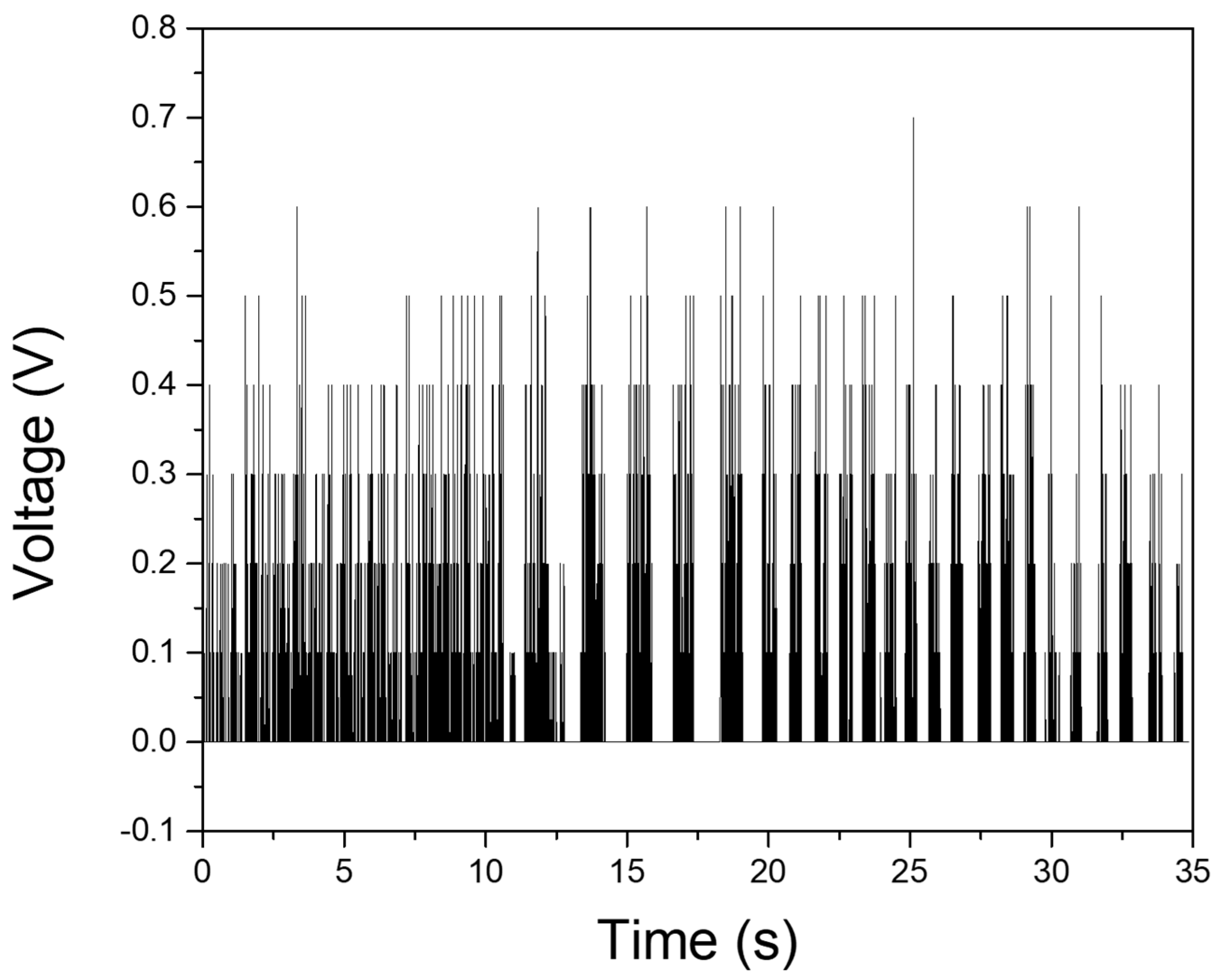

3.2. Characterisation of the Miniaturised Sensors

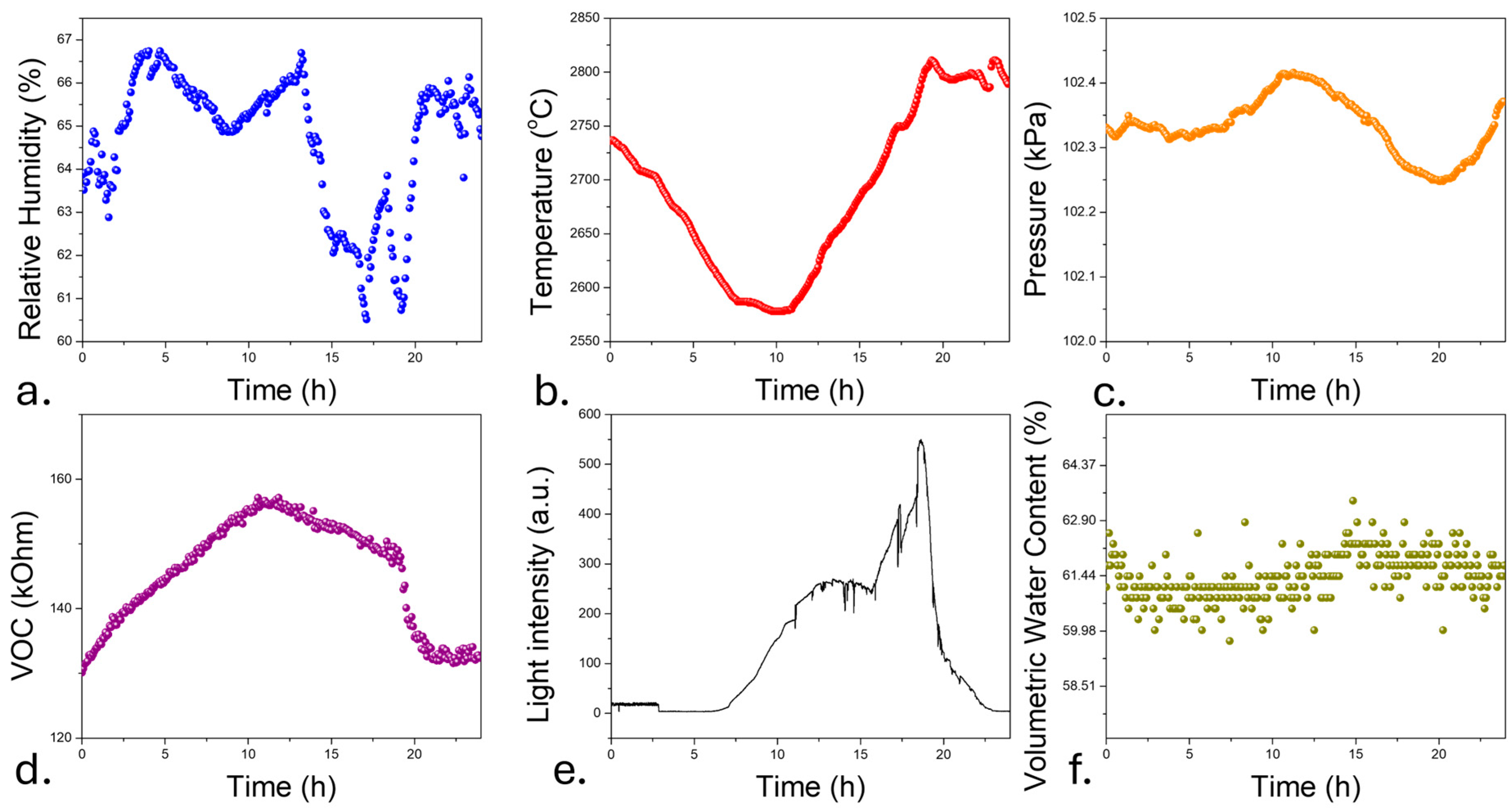

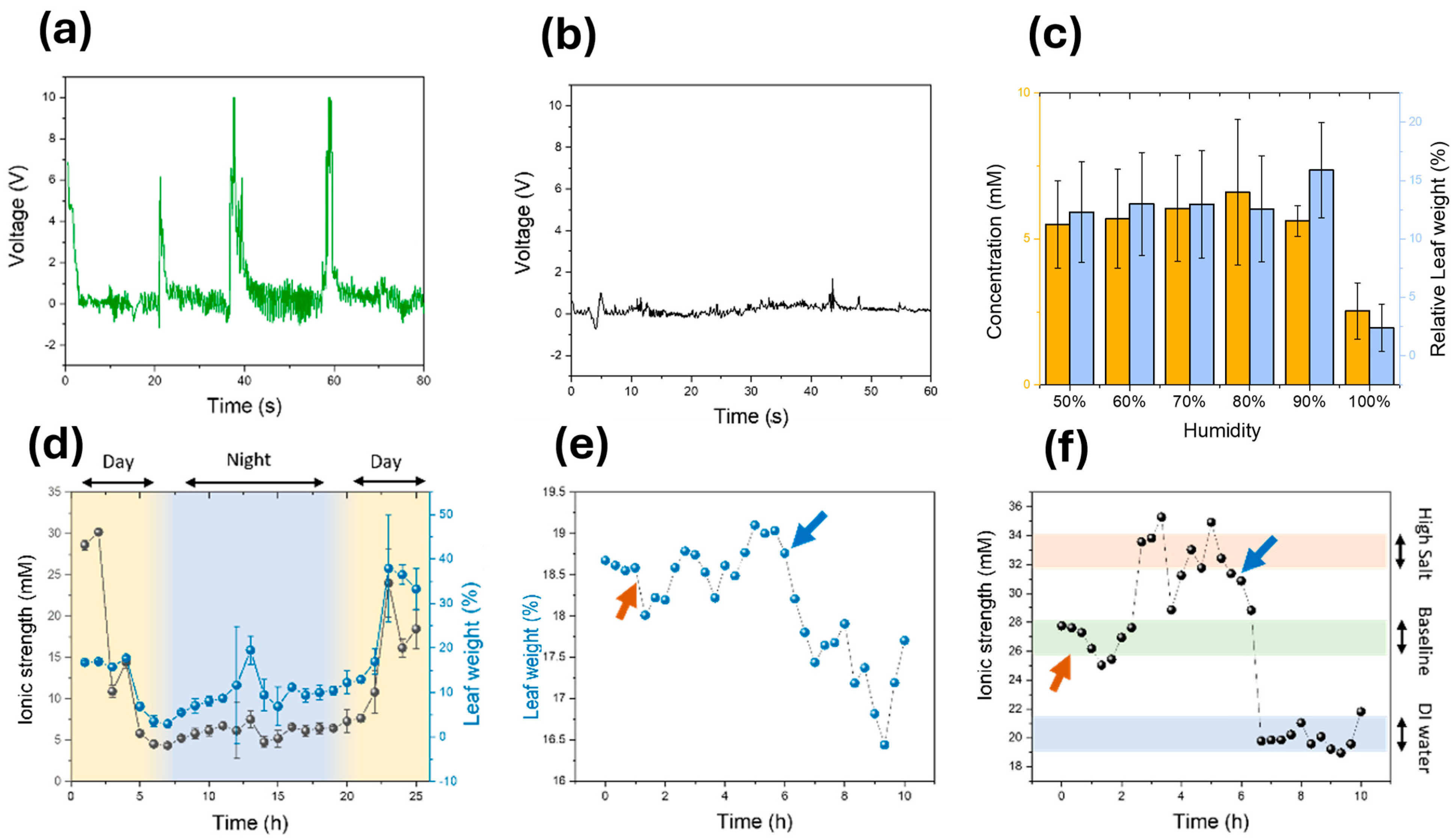

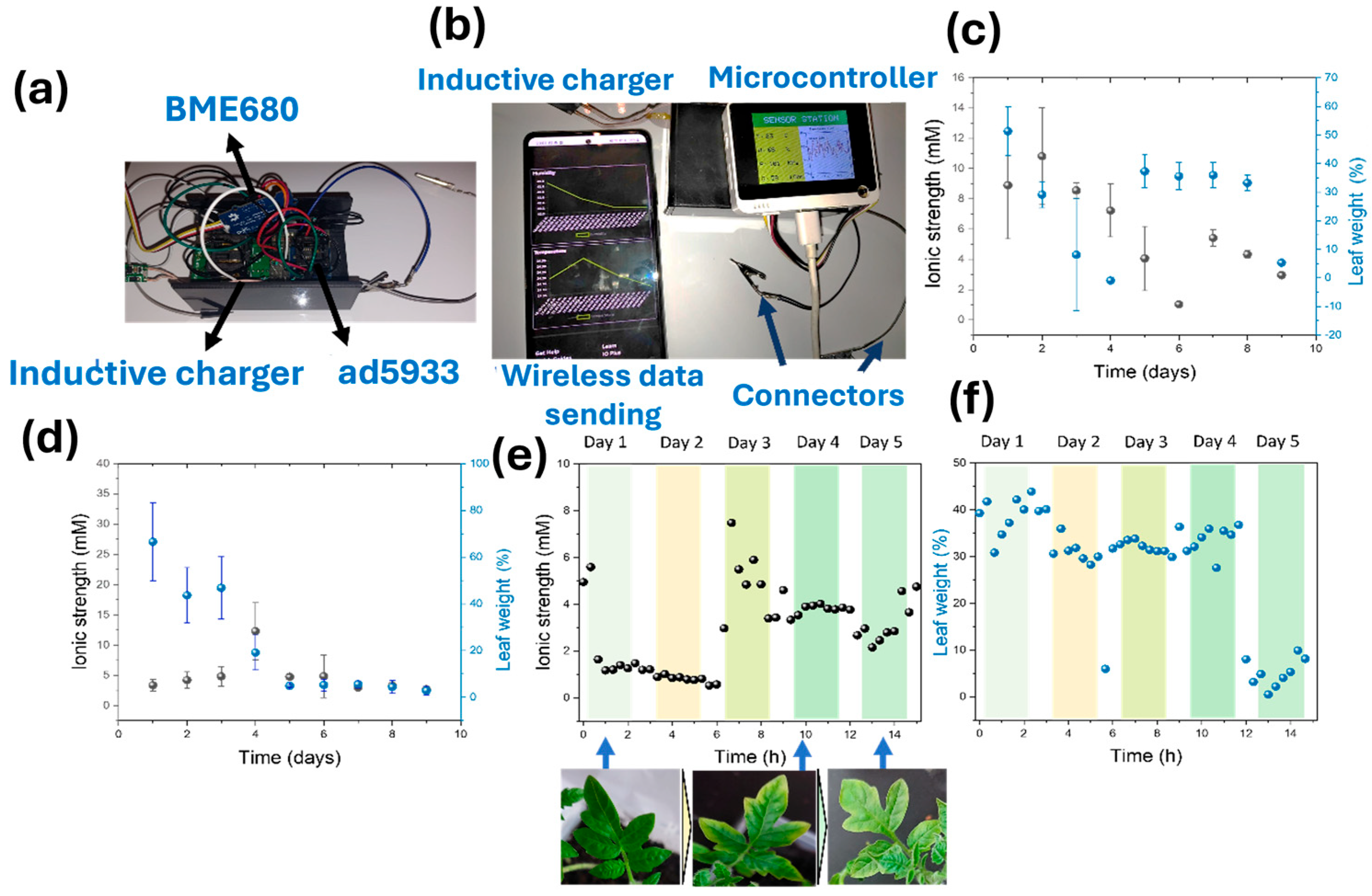

3.3. In Vivo Testing of the Sensors

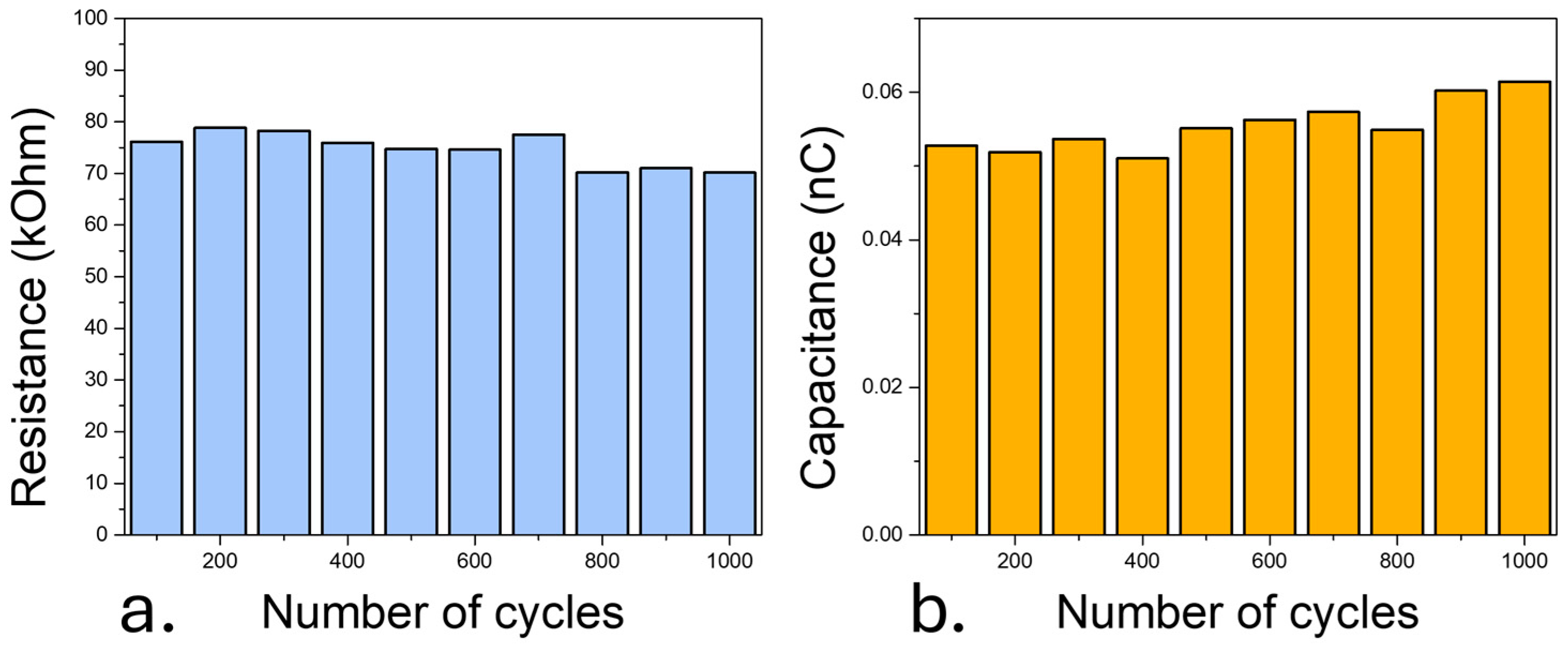

3.4. Long-Term Monitoring of Sensors

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Compound | Amount (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Total Nitrogen (N) | 6 |

| Nitric Nitrogen (N) | 1.2 |

| Ureic Nitrogen (N) | 4.8 |

| Phosphorous Pentoxide | 5 |

| Potassium Oxide | 9 |

| Magnesium | 0.02 |

References

- Lee, G.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, Y. Emerging Wearable Sensors for Plant Health Monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2106475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Said Mohamed, E.; Belal, A.A.; Kotb Abd-Elmabod, S.; El-Shirbeny, M.A.; Gad, A.; Zahran, M.B. Smart farming for improving agricultural management. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2021, 24, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, J.; Wang, C.; Feng, L.; Song, Z.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, C. The Application of Wearable Glucose Sensors in Point-of-Care Testing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 774210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currano, L.J.; Sage, F.C.; Hagedon, M.; Hamilton, L.; Patrone, J.; Gerasopoulos, K. Wearable Sensor System for Detection of Lactate in Sweat. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirovano, P.; Dorrian, M.; Shinde, A.; Donohoe, A.; Brady, A.J.; Moyna, N.M.; Wallace, G.; Diamond, D.; McCaul, M. A wearable sensor for the detection of sodium and potassium in human sweat during exercise. Talanta 2020, 219, 121145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Emaminejad, S.; Nyein, H.Y.Y.; Challa, S.; Chen, K.; Peck, A.; Fahad, H.M.; Ota, H.; Shiraki, H.; Kiriya, D.; et al. Fully integrated wearable sensor arrays for multiplexed in situ perspiration analysis. Nature 2016, 529, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, T.T.S.; Koman, V.B.; Silmore, K.S.; Seo, J.S.; Gordiichuk, P.; Kwak, S.-Y.; Park, M.; Ang, M.C.-Y.; Khong, D.T.; Lee, M.A.; et al. Real-time detection of wound-induced H2O2 signalling waves in plants with optical nanosensors. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Chen, C.; Luo, X.; Zhan, S.; Kim, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Ying, Y.; Liu, X. Cohabiting Plant-Wearable Sensor In Situ Monitors Water Transport in Plant. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, D.; Cimini, S.; Massaroni, C.; D’Amato, R.; Caponero, M.A.; De Gara, L.; Schena, E. Plant Wearable Sensors Based on FBG Technology for Growth and Microclimate Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Teng, C.; Sun, Y.; Cai, L.; Xu, J.-L.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Xiang, L.; Xie, D.; et al. Sprayed, Scalable, Wearable, and Portable NO2 Sensor Array Using Fully Flexible AgNPs-All-Carbon Nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 34485–34493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Paul, R.; Ba Tis, T.; Saville, A.C.; Hansel, J.C.; Yu, T.; Ristaino, J.B.; Wei, Q. Non-invasive plant disease diagnostics enabled by smartphone-based fingerprinting of leaf volatiles. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, K.; Cheng, H.; Huang, X. Multifunctional Stretchable Sensors for Continuous Monitoring of Long-Term Leaf Physiology and Microclimate. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 9522–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ibrahim, H.; Schnable, P.S.; Castellano, M.J.; Dong, L. A Field-Deployable, Wearable Leaf Sensor for Continuous Monitoring of Vapor-Pressure Deficit. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2001246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Fan, R.; Allison, L.K.; Andrew, T.L. On-site identification of ozone damage in fruiting plants using vapor-deposited conducting polymer tattoos. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, T.; Ravindran, P.; Wen, F.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Kumar, P.P.; Chae, E.; Lee, C. All-organic transparent plant e-skin for noninvasive phenotyping. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrinidou, E.; Gabrielsson, R.; Gomez, E.; Crispin, X.; Nilsson, O.; Simon, D.T.; Berggren, M. Electronic plants. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1501136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, L.; Guan, X.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Wei, J.; Ouyang, J. Biocompatible Conductive Polymers with High Conductivity and High Stretchability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 26185–26193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, D.; Wei, H.-Y.; Ho, K.-C.; Chu, C.-W. Highly conductive PEDOT:PSS electrode by simple film treatment with methanol for ITO-free polymer solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9662–9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtakari, D.; Liu, J.; Kumar, V.; Xu, C.; Toivakka, M.; Saarinen, J.J. Conductivity of PEDOT:PSS on Spin-Coated and Drop Cast Nanofibrillar Cellulose Thin Films. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broski, A.; Guo, Y.; Khan, W.A.; Li, W. Characteristics of PEDOT:PSS thin films spin-coated on ITO. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 12th International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 April 2017; pp. 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, J.G.; Worfolk, B.J.; Maloney, S.A.; Hauger, T.C.; Elias, A.L.; Buriak, J.M.; Harris, K.D. Spray coated high-conductivity PEDOT:PSS transparent electrodes for stretchable and mechanically-robust organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 110, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Noh, Y.; Reljin, N.; Treich, G.M.; Hajeb-Mohammadalipour, S.; Guo, Y.; Chon, K.H.; Sotzing, G.A. Screen-Printed PEDOT:PSS Electrodes on Commercial Finished Textiles for Electrocardiography. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37524–37528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouaze, J.C.; Kim, J.H.; Jeon, G.R.; Kim, J.H. Monitoring of Indoor Farming of Lettuce Leaves for 16 Hours Using Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and Double-Shell Model (DSM). Sensors 2022, 22, 9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inácio, P.M.C.; Guerra, R.; Stallinga, P. A path toward transferable PEDOT:PSS-based capacitive sensors: Electrical modeling and fabrication. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 393, 116779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, F.; Janni, M.; Coppedè, N.; Gentile, F.; Manfredi, R.; Bettelli, M.; Zappettini, A. Development of an In Vivo Sensor to Monitor the Effects of Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) Changes to Improve Water Productivity in Agriculture. Sensors 2019, 19, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.I.; Tabassum, S. A hybrid multifunctional physicochemical sensor suite for continuous monitoring of crop health. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janni, M.; Coppede, N.; Bettelli, M.; Briglia, N.; Petrozza, A.; Summerer, S.; Vurro, F.; Danzi, D.; Cellini, F.; Marmiroli, N.; et al. In Vivo Phenotyping for the Early Detection of Drought Stress in Tomato. Plant Phenomics 2019, 2019, 6168209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V.; Straltsova, D.; Medvedev, S.S.; Pozhvanov, G.A.; Sokolik, A.; Yurin, V. Stress-induced electrolyte leakage: The role of K+-permeable channels and involvement in programmed cell death and metabolic adjustment. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajji, M.; Kinet, J.-M.; Lutts, S. The use of the electrolyte leakage method for assessing cell membrane stability as a water stress tolerance test in durum wheat. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 36, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.S.; nia Quartin, V.; chicho Ramalho, J.; Nunes, M.A. Electrolyte leakage and lipid degradation account for cold sensitivity in leaves of Coffea sp. plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V.; Tester, M. Sodium Fluxes through Nonselective Cation Channels in the Plasma Membrane of Protoplasts from Arabidopsis Roots. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hasan, S.A.; Fariduddin, Q.; Ahmad, A. Growth of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) in response to salicylic acid under water stress. J. Plant Interact. 2008, 3, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleski, A.P.; Grossman, J.J. Standardization of electrolyte leakage data and a novel liquid nitrogen control improve measurements of cold hardiness in woody tissue. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppedè, N.; Janni, M.; Bettelli, M.; Maida, C.L.; Gentile, F.; Villani, M.; Ruotolo, R.; Iannotta, S.; Marmiroli, N.; Marmiroli, M.; et al. An in vivo biosensing, biomimetic electrochemical transistor with applications in plant science and precision farming. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, F.; Vurro, F.; Janni, M.; Manfredi, R.; Cellini, F.; Petrozza, A.; Zappettini, A.; Coppedè, N. A Biomimetic, Biocompatible OECT Sensor for the Real-Time Measurement of Concentration and Saturation of Ions in Plant Sap. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2022, 8, 2200092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacci, C.; Abedi, T.; Lee, J.W.; Gabrielsson, E.O.; Berggren, M.; Simon, D.T.; Niittylä, T.; Stavrinidou, E. Diurnal in vivo xylem sap glucose and sucrose monitoring using implantable organic electrochemical transistor sensors. iScience 2021, 24, 101966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhamsin, A.H.; Shetty, S.S.; Fakeih, E.; Martinez, M.S.; Lerma, C.; Mundummal, M.; Wang, J.Y.; Kosel, J.; Al-Babili, S.; Blilou, I.; et al. In vivo dynamics of indole- and phenol-derived plant hormones: Long-term, continuous, and minimally invasive phytohormone sensor. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurro, F.; Manfredi, R.; Bettelli, M.; Bocci, G.; Cologni, A.L.; Cornali, S.; Reggiani, R.; Marchetti, E.; Coppedè, N.; Caselli, S.; et al. In vivo sensing to monitor tomato plants in field conditions and optimize crop water management. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 2479–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theoretical study of contact-mode triboelectric nanogenerators as an effective power source. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3576–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theory of Sliding-Mode Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6184–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, A.S.; Ragoisha, G.A. Progress in Chemometrics Research; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, H.; Kovalchuk, N.; Langridge, P.; Tricker, P.J.; Lopato, S.; Borisjuk, N. The impact of drought on wheat leaf cuticle properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.-J.; Li, X.-D.; Ratnasekera, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.-X.; Song, L.-F.; Zhang, W.-Z.; Wu, W.-H. Arabidopsis CALCIUM-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE8 and CATALASE3 Function in Abscisic Acid-Mediated Signaling and H2O2 Homeostasis in Stomatal Guard Cells under Drought Stress. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Ma, F.; Li, B.; Guo, C.; Hu, T.; Zhang, M.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhan, X. A bHLH transcription factor, SlbHLH96, promotes drought tolerance in tomato. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghannam, F.; Alayed, M.; Alfihed, S.; Sakr, M.A.; Almutairi, D.; Alshamrani, N.; Al Fayez, N. Recent Progress in PDMS-Based Microfluidics Toward Integrated Organ-on-a-Chip Biosensors and Personalized Medicine. Biosensors 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, I.D.; McCluskey, D.K.; Tan, C.K.L.; Tracey, M.C. Mechanical characterization of bulk Sylgard 184 for microfluidics and microengineering. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2014, 24, 035017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, T.C.; Bondar, V.I.; Nagai, K.; Freeman, B.D.; Pinnau, I. Gas sorption, diffusion, and permeation in poly(dimethylsiloxane). J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Physic 2000, 38, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Franeker, J.J.; Voorthuijzen, W.P.; Gorter, H.; Hendriks, K.H.; Janssen, R.A.J.; Hadipour, A.; Andriessen, R.; Galagan, Y. All-solution-processed organic solar cells with conventional architecture. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 117, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardes, A.M.; Janssen, R.A.J.; Kemerink, M. A Morphological Model for the Solvent-Enhanced Conductivity of PEDOT:PSS Thin Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Allison, L.; Andrew, T. Vapor-printed polymer electrodes for long-term, on-demand health monitoring. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw0463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Choy, K.L. Highly selective and robust nanocomposite-based sensors for potassium ions detection. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 23, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Choy, K.-L. Integration of an Aerosol-Assisted Deposition Technique for the Deposition of Functional Biomaterials Applied to the Fabrication of Miniaturised Ion Sensors. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Dong, X.; Chen, C.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, S. Effects of Leaf Surface Roughness and Contact Angle on In Vivo Measurement of Droplet Retention. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Wang, C.; Zhao, R.; Du, L.; Fang, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Z. Review of Stratum Corneum Impedance Measurement in Non-Invasive Penetration Application. Biosensors 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repo, T.; Korhonen, A.; Laukkanen, M.; Lehto, T.; Silvennoinen, R. Detecting mycorrhizal colonisation in Scots pine roots using electrical impedance spectra. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 121, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyman, A. Dielectric properties of tissues; variation with age and their relevance in exposure of children to electromagnetic fields; state of knowledge. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011, 107, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, S.; Schjoerring, J.K. Apoplastic pH and Ammonium Concentration in Leaves of Brassica napus L. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattelmacher, B. The apoplast and its significance for plant mineral nutrition. New Phytol. 2001, 149, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, M.S.; Gadallah, S.I.; Said, L.A.; Eltawil, A.M.; Radwan, A.G.; Madian, A.H. Plant stem tissue modeling and parameter identification using metaheuristic optimization algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Li, J.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, Q. Development of an interdigitated electrode sensor for monitoring tobacco leaf relative water content in bulk curing barn. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väinölä, A.; Repo, T. Impedance Spectroscopy in Frost Hardiness Evaluation of Rhododendron Leaves. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; El-Keblawy, A.; Akhtar, N.; Elwakil, A.S. Electrical Impedance Spectroscopy in Plant Biology. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 52; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 395–416. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, L.; Peradotto, S.; Sanginario, A.; Ros, P.M.; Shacham-Diamand, Y.; Demarchi, D. In-Vivo Monitoring for Electrical Expression of Plant Living Parameters by an Impedance Lab System. In Proceedings of the 2019 26th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Genoa, Italy, 27–29 November 2019; pp. 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, H.-S.; Chen, Y.-L.; Zhang, P.-Y.; Hsiao, Y.-S. Additive Blending Effects on PEDOT:PSS Composite Films for Wearable Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 13384–13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez Mahmud, M.A.; Huda, N.; Farjana, S.H.; Asadnia, M.; Lang, C. Recent Advances in Nanogenerator-Driven Self-Powered Implantable Biomedical Devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dahlström, C.; Zou, H.; Jonzon, J.; Hummelgård, M.; Örtegren, J.; Blomquist, N.; Yang, Y.; Andersson, H.; Olsen, M.; et al. Cellulose-Based Fully Green Triboelectric Nanogenerators with Output Power Density of 300 W m−2. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, Y.; Jia, X.; Zou, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z.L.; Cao, X. Natural Leaf Made Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Harvesting Environmental Mechanical Energy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakmuangpak, S.; Prada, T.; Mongkolthanaruk, W.; Harnchana, V.; Pinitsoontorn, S. Engineering Bacterial Cellulose Films by Nanocomposite Approach and Surface Modification for Biocompatible Triboelectric Nanogenerator. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Feng, C.-P.; Deng, B.-W.; Yin, B.; Yang, M.-B. Facile method to enhance output performance of bacterial cellulose nanofiber based triboelectric nanogenerator by controlling micro-nano structure and dielectric constant. Nano Energy 2019, 62, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bießmann, L.; Kreuzer, L.P.; Widmann, T.; Hohn, N.; Moulin, J.-F.; Müller-Buschbaum, P. Monitoring the Swelling Behavior of PEDOT:PSS Electrodes under High Humidity Conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9865–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Han, D.-C.; Shin, H.-J.; Yeom, S.-H.; Ju, B.-K.; Lee, W. PEDOT:PSS-Based Temperature-Detection Thread for Wearable Devices. Sensors 2018, 18, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasena, R.D.I.G. Inherent asymmetry of the current output in a triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2020, 76, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Green plant-based triboelectricity system for green energy harvesting and contact warning. EcoMat 2021, 3, e12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Bu, X.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, R.; Yang, L.; Zhang, K. A single-electrode mode triboelectric nanogenerator based on natural leaves for harvesting energy. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 2743–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chang, Y.; Zhu, Z. A Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Bamboo Leaf for Biomechanical Energy Harvesting and Self-Powered Touch Sensing. Electronics 2024, 13, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Yin, X.; Yu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X. Chemically Functionalized Natural Cellulose Materials for Effective Triboelectric Nanogenerator Development. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1700794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.T. Self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator with enhanced surface charge density for dynamic multidirectional pressure sensing. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Jahan, N.; Chen, G.; Ren, D.; Guo, L. Sensing of Abiotic Stress and Ionic Stress Responses in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yang, Y. How Plants Tolerate Salt Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5914–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, K.E.; Webb, A.A.R. Circadian Rhythms in Stomata: Physiological and Molecular Aspects. In Rhythms in Plants: Dynamic Responses in a Dynamic Environment; Mancuso, S., Shabala, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 231–255. [Google Scholar]

- Garlando, U.; Calvo, S.; Barezzi, M.; Sanginario, A.; Motto Ros, P.; Demarchi, D. Ask the plants directly: Understanding plant needs using electrical impedance measurements. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelatty, O.; Chen, X.; Alghaihab, A.; Wentzloff, D. Bluetooth Communication Leveraging Ultra-Low Power Radio Design. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2021, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleman, J.; Otis, B. A Sub-Microwatt Low-Noise Amplifier for Neural Recording. In Proceedings of the 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 22–26 August 2007; pp. 3930–3933. [Google Scholar]

| PEDOT:PSS/PDMS—tomato leaf | ~10 | 5.14 | 5.14 × 10−6 | 25.7 | 0.072 | This work |

| Natural-leaf-based single-electrode TENG | 12 | 3.8 | 4.2 × 10−6 | 16.8 | 0.056 | [75] |

| Bamboo-leaf TENG | ~191 | ~5.0 | - | - | - | [76] |

| Nitro/Methyl-CNF TENG | 8 | 9 | - | - | - | [77] |

| Bacterial-cellulose/ZnO hybrid bio-TENG | 58 | 5.8 | - | - | 0.042 | [69] |

| PDMS doped with carbon black and polyvinylpyrrolidone | 50 | 5.5 | 6.2 × 10−7 | 3.1 | 0.45 | [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Kempson, H.; Haseloff, J. Transparent PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Leaf Tattoos for Multiplexed Plant Health Monitoring and Energy Harvesting. Biosensors 2025, 15, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120805

Ruiz-Gonzalez A, Kempson H, Haseloff J. Transparent PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Leaf Tattoos for Multiplexed Plant Health Monitoring and Energy Harvesting. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120805

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Gonzalez, Antonio, Harriet Kempson, and Jim Haseloff. 2025. "Transparent PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Leaf Tattoos for Multiplexed Plant Health Monitoring and Energy Harvesting" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120805

APA StyleRuiz-Gonzalez, A., Kempson, H., & Haseloff, J. (2025). Transparent PEDOT:PSS/PDMS Leaf Tattoos for Multiplexed Plant Health Monitoring and Energy Harvesting. Biosensors, 15(12), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120805