Opportunities and Challenges in Gas Sensor Technologies for Accurate Detection of COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

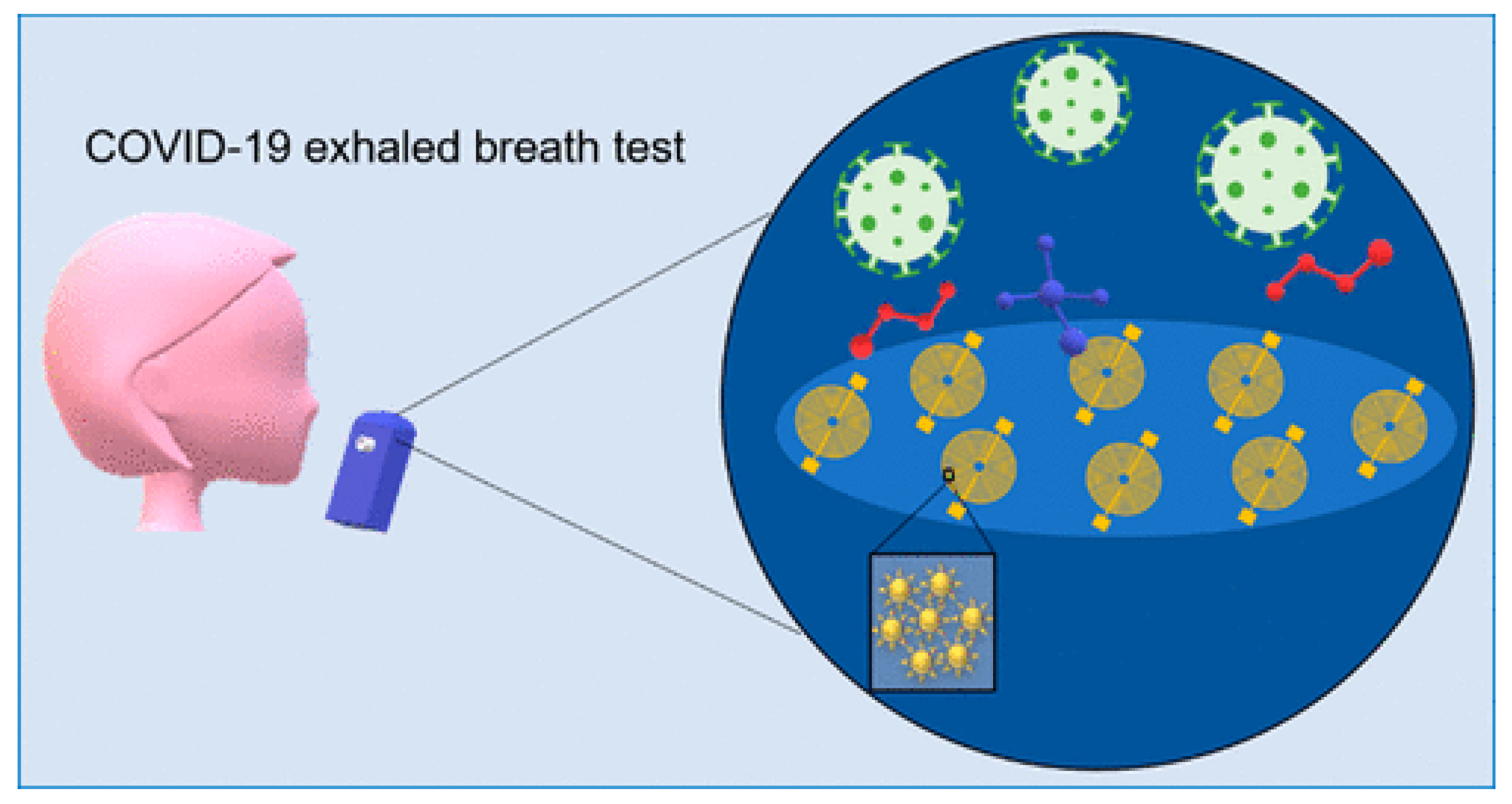

2. Biomarkers in EB for COVID-19 Detection

3. Advancements in Gas Sensors for COVID-19 Detection

4. Summary and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOC | volatile organic compounds |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| NH3 | ammonia |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| FeNO | fractional exhaled nitric oxide |

| MOS E-nose | metal oxide semiconductor electronic nose |

| QCM biosensor | quartz crystal microbalance biosensor |

| SERS biosensor | surface-enhanced raman scattering biosensor |

| FET/BioFET | field-effect transistor/biological field-effect transistor |

| AUC | area under the curve. |

| pM–fM | picomolar to femtomolar |

| CNN | convolutional neural network |

| SVMs | support vector machines |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| RT-qPCR | reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

References

- Verity, R.; Okell, L.C.; Dorigatti, I.; Winskill, P.; Whittaker, C.; Imai, N.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; Thompson, H.; Walker, P.G.T.; Fu, H.; et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallah, S.I.; Ghorab, O.K.; Al-Salmi, S.; Abdellatif, O.S.; Tharmaratnam, T.; Iskandar, M.A.; Sefen, J.A.N.; Sidhu, P.; Atallah, B.; El-Lababidi, R.; et al. COVID-19: Breaking down a global health crisis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, P.; Hu, C.; Mao, H. Detecting the Coronavirus (COVID-19). ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2283–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Naiyer, S.; Mansuri, S.; Soni, N.; Singh, V.; Bhat, K.H.; Singh, N.; Arora, G.; Mansuri, M.S. COVID-19 Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review of the RT-qPCR Method for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Sun, X.; Dai, Z.; Gao, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhou, B.; Wu, J.; Wen, W. Point-of-care testing detection methods for COVID-19. Lab. A Chip. 2021, 21, 1634–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.; Mueller, R.; Shipley, G.; Nolan, T. COVID-19 and Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR-Facts and Fallacies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Chandra, P. Clinically practiced and commercially viable nanobio engineered analytical methods for COVID-19 diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Dashtipour, K.; Ansari, S.; Shah, S.A.; Khalid, A.; Imran, M.A. A Review of the State of the Art in Non-Contact Sensing for COVID-19. Sensors 2020, 20, 5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raajan, N.R.; Lakshmi, V.S.R.; Prabaharan, N. Non-Invasive Technique-Based Novel Corona(COVID-19) Virus Detection Using CNN. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2021, 44, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filchakova, O.; Dossym, D.; Ilyas, A.; Kuanysheva, T.; Abdizhamil, A.; Bukasov, R. Review of COVID-19 testing and diagnostic methods. Talanta 2022, 244, 123409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.; Pandey, S.; Shrestha, R.; Pokharel, K.; Ligler, F.S.; Neupane, B.B. Review of analytical performance of COVID-19 detection methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juthi, R.T.; Sazed, S.A.; Zamil, M.F.; Alam, M.S. Clinical Evaluation of Three Commercial RT-PCR Kits for Routine COVID-19 Diagnosis. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, L.M.S.; Galvis, M.L.D.; Campos, M.A.J.; Lozano-Parra, A.; Villamizar, L.A.R.; Arenas, M.O.; Martínez-Vega, R.A.; Cala, L.M.V.; Bautista, L.E. Validation of RT-qPCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in saliva specimens. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahajpal, N.S.; Mondal, A.K.; Ananth, S.; Njau, A.; Jones, K.; Ahluwalia, P.; Oza, E.; Ross, T.M.; Kota, V.; Kothandaraman, A.; et al. Clinical validation of a multiplex PCR-based detection assay using saliva or nasopharyngeal samples for SARS-Cov-2, influenza A and B. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subali, A.D.; Wiyono, L.; Yusuf, M.; Zaky, M.F.A. The potential of volatile organic compounds-based breath analysis for COVID-19 screening: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 102, 115589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Sawan, M. COVID-19 diagnostic methods and detection techniques. Encycl. Sens. Biosens. 2022, 3, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

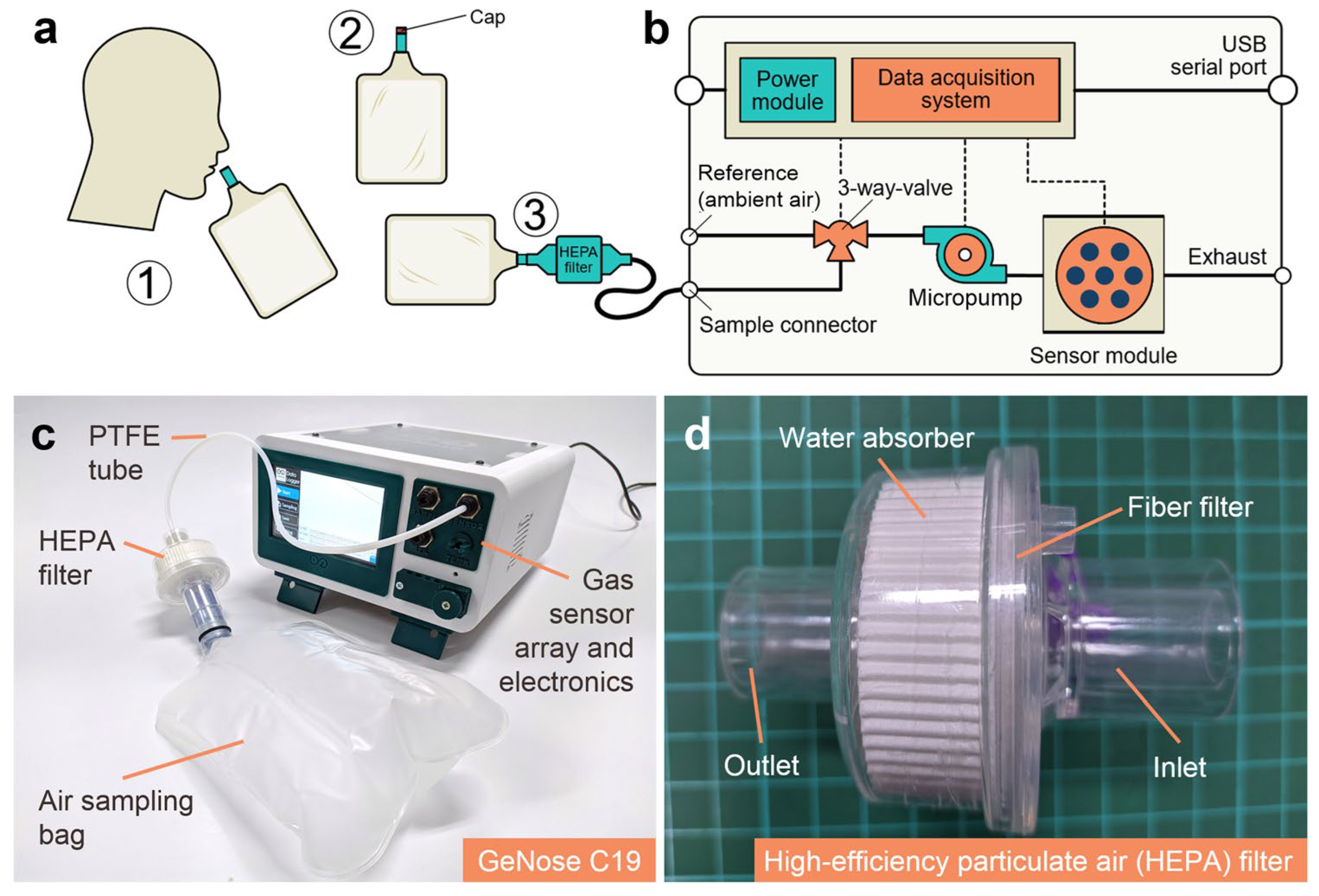

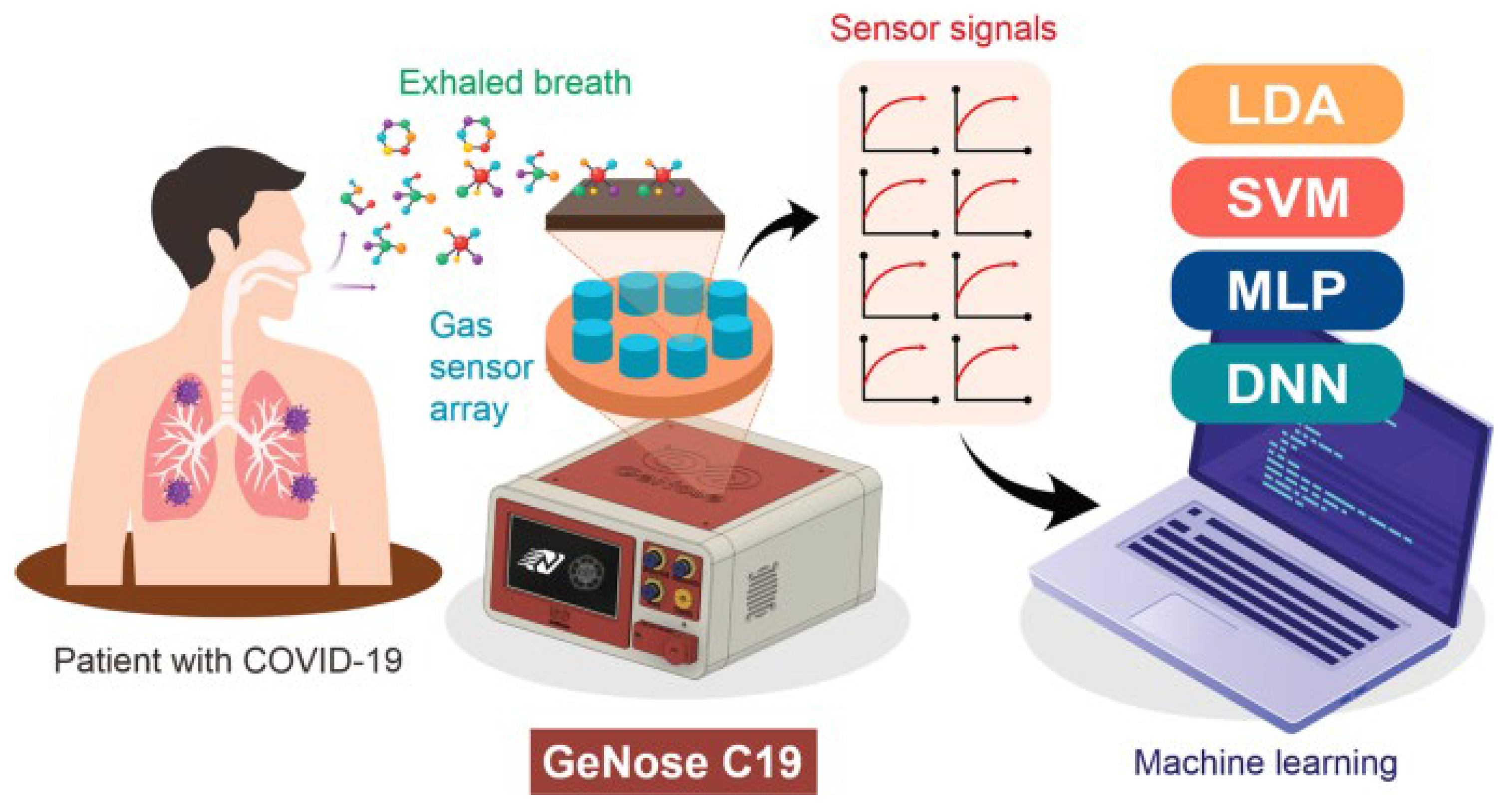

- Nurputra, D.K.; Kusumaatmaja, A.; Hakim, M.S.; Hidayat, S.N.; Julian, T.; Sumanto, B.; Mahendradhata, Y.; Saktiawati, A.M.I.; Wasisto, H.S.; Triyana, K. Fast and noninvasive electronic nose for sniffing out COVID-19 based on exhaled breath-print recognition. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Itoh, T.; Shin, W.; Sawano, M. Machine-learning-assisted sensor array for detecting COVID-19 through simulated exhaled air. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 400, 134883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.A.; Xu, Q.; Sunkara, J.; Woodbury, R.; Brown, K.; Huang, J.J.; Xie, Z.; Chen, X.; Fu, X.A.; Huang, J. A comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review of breath analysis in detection of COVID-19 through Volatile organic compounds. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 109, 116309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Datta, B.; Ashish, A.; Dutta, G. A comprehensive review on current COVID-19 detection methods: From lab care to point of care diagnosis. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Walid, M.A.A.; Galib, S.M.S.; Azad, M.M.; Rahman, W.; Shafi, A.S.M.; Rahman, M.M. COVID-19 detection from chest CT images using optimized deep features and ensemble classification. Syst. Soft Comput. 2024, 6, 200077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Houby, E.M.F. COVID-19 detection from chest X-ray images using transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannini, G.; Haick, H.; Garoli, D. Detecting COVID-19 from Breath: A Game Changer for a Big Challenge. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellarmino, N.; Cantoro, R.; Castelluzzo, M.; Correale, R.; Squillero, G.; Bozzini, G.; Castelletti, F.; Ciricugno, C.; Dalla Gasperina, D.; Dentali, F.; et al. COVID-19 detection from exhaled breath. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Basu, M.; Chakraborty, D.; Ghosh, P.; Ghosh, M.K. Unraveling COVID-19 Diagnostics: A Roadmap for Future Pandemic. Nat. Cell Sci. 2024, 2, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, W.F.; Oluwayelu, D.O. Real-time RT-PCR for COVID-19 diagnosis: Challenges and prospects. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Han, H.; Liu, F.; Lv, Z.; Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, C. Positive rate of RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 4880 cases from one hospital in Wuhan, China, from Jan to Feb 2020. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 505, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahamtan, A.; Ardebili, A. Real-time RT-PCR in COVID-19 detection: Issues affecting the results. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, O.; Martiny, D.; Rochas, O.; van Belkum, A.; Kozlakidis, Z. Considerations for diagnostic COVID-19 tests. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlet, J.; Petillon, C.; Ragot, E.; Abou El Fattah, Y.; Guillon, A.; Marchand Adam, S.; Lemaignen, A.; Bernard, L.; Desoubeaux, G.; Blasco, H.; et al. Clinical performance of four immunoassays for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, including a prospective analysis for the diagnosis of COVID-19 in a real-life routine care setting. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 132, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, P.K.; Ampajwala, M.; Chappel, C.; Gvozden, A.B.; Hoppers, M.; Wang, M.; Rosen, R.; Young, S.; Zissman, E.; Montano, M. A Rapid, High-Sensitivity SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Immunoassay to Aid Diagnosis of Acute COVID-19 at the Point of Care: A Clinical Performance Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinnes, J.; Deeks, J.J.; Adriano, A.; Berhane, S.; Davenport, C.; Dittrich, S.; Emperador, D.; Takwoingi, Y.; Cunningham, J.; Beese, S.; et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, Cd013705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krone, M.; Gütling, J.; Wagener, J.; Lâm, T.T.; Schoen, C.; Vogel, U.; Stich, A.; Wedekink, F.; Wischhusen, J.; Kerkau, T.; et al. Performance of Three SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassays, Three Rapid Lateral Flow Tests, and a Novel Bead-Based Affinity Surrogate Test for the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Human Serum. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e0031921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brümmer, L.E.; Katzenschlager, S.; Gaeddert, M.; Erdmann, C.; Schmitz, S.; Bota, M.; Grilli, M.; Larmann, J.; Weigand, M.A.; Pollock, N.R.; et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: A living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, T.C.; Kwee, R.M. Chest CT in COVID-19: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. RadioGraphics 2020, 40, 1848–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-P.; Yang, X.; Xiong, M.; Mao, X.; Jin, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, S.; Chang, H. Development and validation of chest CT-based imaging biomarkers for early stage COVID-19 screening. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1004117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Ocampo, E.; Villamizar-Peña, R.; Holguin-Rivera, Y.; Escalera-Antezana, J.P.; Alvarado-Arnez, L.E.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Henao-Martinez, A.F.; et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 34, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Momani, H. A Literature Review on the Relative Diagnostic Accuracy of Chest CT Scans versus RT-PCR Testing for COVID-19 Diagnosis. Tomography 2024, 10, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, W.; Cordell, R.L.; Wilde, M.J.; Richardson, M.; Carr, L.; Sundari Devi Dasi, A.; Hargadon, B.; Free, R.C.; Monks, P.S.; Brightling, C.E.; et al. Diagnosis of COVID-19 by exhaled breath analysis using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, A.; Borys, S.; Sikorska, K.; Drozdowska, K.; Smulko, J.M. Clinical studies of detecting COVID-19 from exhaled breath with electronic nose. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, N.; Clarke, C. Nanostructured Gas Sensors for Medical and Health Applications: Low to High Dimensional Materials. Biosensors 2019, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, R.P.; Larracy, R.; Morrell, C.B.; Ranjbar, M.; Le Roux, J.; Whetstone, C.E.; Boudreau, M.; Poitras, P.F.; Srinathan, T.; Cheng, E.; et al. Machine learning enabled detection of COVID-19 pneumonia using exhaled breath analysis: A proof-of-concept study. J. Breath. Res. 2024, 18, 026009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.D.; Forse, L.B. Potential for Early Noninvasive COVID-19 Detection Using Electronic-Nose Technologies and Disease-Specific VOC Metabolic Biomarkers. Sensors 2023, 23, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juste-Dolz, A.; Teixeira, W.; Pallás-Tamarit, Y.; Carballido-Fernández, M.; Carrascosa, J.; Morán-Porcar, Á.; Redón-Badenas, M.; Pla-Roses, M.G.; Tirado-Balaguer, M.D.; Remolar-Quintana, M.J.; et al. Real-world evaluation of a QCM-based biosensor for exhaled air. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 7369–7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobysh, M.; Ramanaviciene, A.; Viter, R.; Chen, C.F.; Samukaite-Bubniene, U.; Ratautaite, V.; Ramanavicius, A. Biosensors for the Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Virus and Diagnosis of COVID-19 Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyadi, F.; Kavruk, M.; Ucak, S.; Cetin, B.; Bayramoglu, G.; Dursun, A.D.; Arica, Y.; Ozalp, V.C. Real-Time Biosensing Bacteria and Virus with Quartz Crystal Microbalance: Recent Advances, Opportunities, and Challenges. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 2888–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Su Jeon, C.; Choi, N.; Moon, J.I.; Min Lee, K.; Hyun Pyun, S.; Kang, T.; Choo, J. Sensitive and reproducible detection of SARS-CoV-2 using SERS-based microdroplet sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, C.; Du, X.; Zhang, Z. Research progress of biosensors for detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants based on ACE2. Talanta 2023, 251, 123813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Shi, J.; Yang, Y. Recent development of surface-enhanced Raman scattering for biosensing. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.H.; Aliyu, B.; Sharel, P.E.; Amin-Nordin, S.; Chee, H.Y. Diagnostic accuracy of aptamer-based biosensors for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 compared to RT-PCR: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, T.D.; Klawa, S.J.; Jian, T.; Kim, S.H.; Papanikolas, M.J.; Freeman, R.; Schultz, Z.D. Catching COVID: Engineering Peptide-Modified Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Sensors for SARS-CoV-2. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 3436–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymborski, T.R.; Berus, S.M.; Nowicka, A.B.; Słowiński, G.; Kamińska, A. Machine Learning for COVID-19 Determination Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, M.J.; Baek, S.-H.; Choi, M.; Ku, K.B.; Lee, C.-S.; Jun, S.; Park, D.; Kim, H.G.; et al. Rapid Detection of COVID-19 Causative Virus (SARS-CoV-2) in Human Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens Using Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensor. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5135–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.H.; Cao, B.P.; Xiao, Q.; Wei, D. The Application of Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors in COVID-19 Detection Technology: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Feng, L.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Tang, W.; Yan, F. Recent Advances in Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensors for Label-Free Detection of SARS-CoV-2. Small Sci. 2024, 4, 2300058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deol, P.; Madhwal, A.; Sharma, G.; Kaushik, R.; Malik, Y.S. CRISPR use in diagnosis and therapy for COVID-19. Methods Microbiol. 2022, 50, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Yang, L.; Han, M.; Xu, H.; Ding, W.; Dong, X. CRISPR-cas technology: A key approach for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1158672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.Y.; Yin, X.; Huang, Y.T.; Ye, Q.Q.; Chen, S.Q.; Cao, X.J.; Xie, T.A.; Guo, X.G. Evaluation of CRISPR-Based Assays for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Yonsei Med. J. 2022, 63, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fozouni, P.; Son, S.; Díaz de León Derby, M.; Knott, G.J.; Gray, C.N.; D’Ambrosio, M.V.; Zhao, C.; Switz, N.A.; Kumar, G.R.; Stephens, S.I.; et al. Amplification-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR-Cas13a and mobile phone microscopy. Cell 2021, 184, 323–333.e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, B.J.; Ali, N.A.; Mohd-Naim, N.F.B.; Ahmed, M.U. Exploiting the Specificity of CRISPR/Cas System for Nucleic Acids Amplification-Free Disease Diagnostics in the Point-of-Care. Chem. Bio Eng. 2024, 1, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cho, I.-H.; Kadam, U.S. CRISPR-Cas-Based Diagnostics in Biomedicine: Principles, Applications, and Future Trajectories. Biosensors 2025, 15, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, R.; Tang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qin, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, C. One-pot MCDA-CRISPR-Cas-based detection platform for point-of-care testing of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1503356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, S.; Lu, M.T.; Yeh, C.Y.; Ko, N.Y. Physiological Sensors Equipped in Wearable Devices for Management of Long COVID Persisting Symptoms: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonini, L.; Shawen, N.; Botonis, O.; Fanton, M.; Jayaraman, C.; Mummidisetty, C.K.; Shin, S.Y.; Rushin, C.; Jenz, S.; Xu, S.; et al. Rapid Screening of Physiological Changes Associated With COVID-19 Using Soft-Wearables and Structured Activities: A Pilot Study. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2021, 9, 4900311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, S.H.R.; Ng, Y.J.X.; Lau, Y.; Lau, S.T. Wearable technology for early detection of COVID-19: A systematic scoping review. Prev. Med. 2022, 162, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, T.; Wang, M.; Metwally, A.A.; Bogu, G.K.; Brooks, A.W.; Bahmani, A.; Alavi, A.; Celli, A.; Higgs, E.; Dagan-Rosenfeld, O.; et al. Pre-symptomatic detection of COVID-19 from smartwatch data. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikoo, G.A.; Arshad, F.; Hassan, I.U.; Awan, T.; Salim, H.; Pedram, M.Z.; Ahmed, W.; Patel, V.; Karakoti, A.S.; Vinu, A. Nanomaterials-based sensors for the detection of COVID-19: A review. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 7, e10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pani, S.K.; Dash, S.; dos Santos, W.P.; Chan Bukhari, S.A.; Flammini, F.; Flammini, F.; Dash, S.; Chan Bukhari, S.A.; dos Santos, W.P.; Pani, S.K. Assessing COVID-19 and Other Pandemics and Epidemics Using Computational Modelling and Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, P.C.; Raposo, M.; Vassilenko, V. Breath volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as biomarkers for the diagnosis of pathological conditions: A review. Biomed. J. 2023, 46, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J. Exhaled biomarkers. Chest 2006, 130, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J. Biomarkers of some pulmonary diseases in exhaled breath. Biomarkers 2002, 7, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, Z.; Blaser, A.; Kavianynejad, K.; Torrella, C.; Nsubuga, L.; Mishra, Y.; Rubahn, H.-G.; De Oliveira Hansen, R. Breath Biomarkers as Disease Indicators: Sensing Techniques Approach for Detecting Breath Gas and COVID-19. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöckler, J.; Mizaikoff, B.; Díaz de León-Martínez, L. SARS CoV-2 infection screening via the exhaled breath fingerprint obtained by FTIR spectroscopic gas-phase analysis. A proof of concept. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 302, 123066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liangou, A.; Tasoglou, A.; Huber, H.J.; Wistrom, C.; Brody, K.; Menon, P.G.; Bebekoski, T.; Menschel, K.; Davidson-Fiedler, M.; DeMarco, K.; et al. A method for the identification of COVID-19 biomarkers in human breath using Proton Transfer Reaction Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 42, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Shetti, N.P.; Jagannath, S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Electrochemical sensors for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 132966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruszkiewicz, D.M.; Sanders, D.; O’Brien, R.; Hempel, F.; Reed, M.J.; Riepe, A.C.; Bailie, K.; Brodrick, E.; Darnley, K.; Ellerkmann, R.; et al. Diagnosis of COVID-19 by analysis of breath with gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry—A feasibility study. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsin, N.; Sriphumrat, K.; Mano, P.; Kongpatpanich, K.; Namuangruk, S. Metal-organic framework MIL-100(Fe) as a promising sensor for COVID-19 biomarkers detection. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 343, 112187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerz, A.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Current state of knowledge on the metal oxide based gas sensing mechanism. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 358, 131531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Lv, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, A.; Feng, C. Semiconductor Metal Oxides as Chemoresistive Sensors for Detecting Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors 2019, 19, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidinger, M.; Sauerwald, T.; Conrad, T.; Reimringer, W.; Ventura, G.; Schütze, A. Selective Detection of Hazardous Indoor VOCs Using Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. Procedia Eng. 2014, 87, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, R.; Hajra, S.; Rajaitha, P.M.; Mistewicz, K.; Kim, H.J. Recent advances in multifunctional materials for gas sensing applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.C.; Hu, B. Mass Spectrometry-Based Human Breath Analysis: Towards COVID-19 Diagnosis and Research. J. Anal. Test. 2021, 5, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadzirah, S.; Mohamad Zin, N.; Khalid, A.; Abu Bakar, N.F.; Kamarudin, S.S.; Zulfakar, S.S.; Kon, K.W.; Muhammad Azami, N.A.; Low, T.Y.; Roslan, R.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Environment: Current Surveillance and Effective Data Management of COVID-19. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 3083–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, A.; Jafari Navimipour, N.; Unal, M.; Toumaj, S. Machine learning applications for COVID-19 outbreak management. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 15313–15348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamy, K.V.; Sasi Koushik, D.S.; Chidire, S.V. COVID-19 Detection Using Decision Tree, Support Vector Machine, Random Forest. Int. J. Embed. Syst. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 9, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Roquencourt, C.; Salvator, H.; Bardin, E.; Lamy, E.; Farfour, E.; Naline, E.; Devillier, P.; Grassin-Delyle, S. Enhanced real-time mass spectrometry breath analysis for the diagnosis of COVID-19. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Zhang, C.; Feng, H.; Yao, M. COVID-19 screening using breath-borne volatile organic compounds. J. Breath. Res. 2021, 15, 047104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Lin, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yang, S. Rational Design and Application of Breath Sensors for Healthcare Monitoring. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.J.; Li, Y.J.; Wu, C.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Zan, H.W.; Meng, H.F.; Hsieh, M.H.; Lai, C.S.; Tian, Y.C. Breath Ammonia Is a Useful Biomarker Predicting Kidney Function in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, D.; Hua, L.; Chen, C.; Li, D.; Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, H.; Leng, S. Breath-by-breath measurement of exhaled ammonia by acetone-modifier positive photoionization ion mobility spectrometry via online dilution and purging sampling. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 13, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, P.P.; Gregory, O.J. Sensors for the detection of ammonia as a potential biomarker for health screening. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

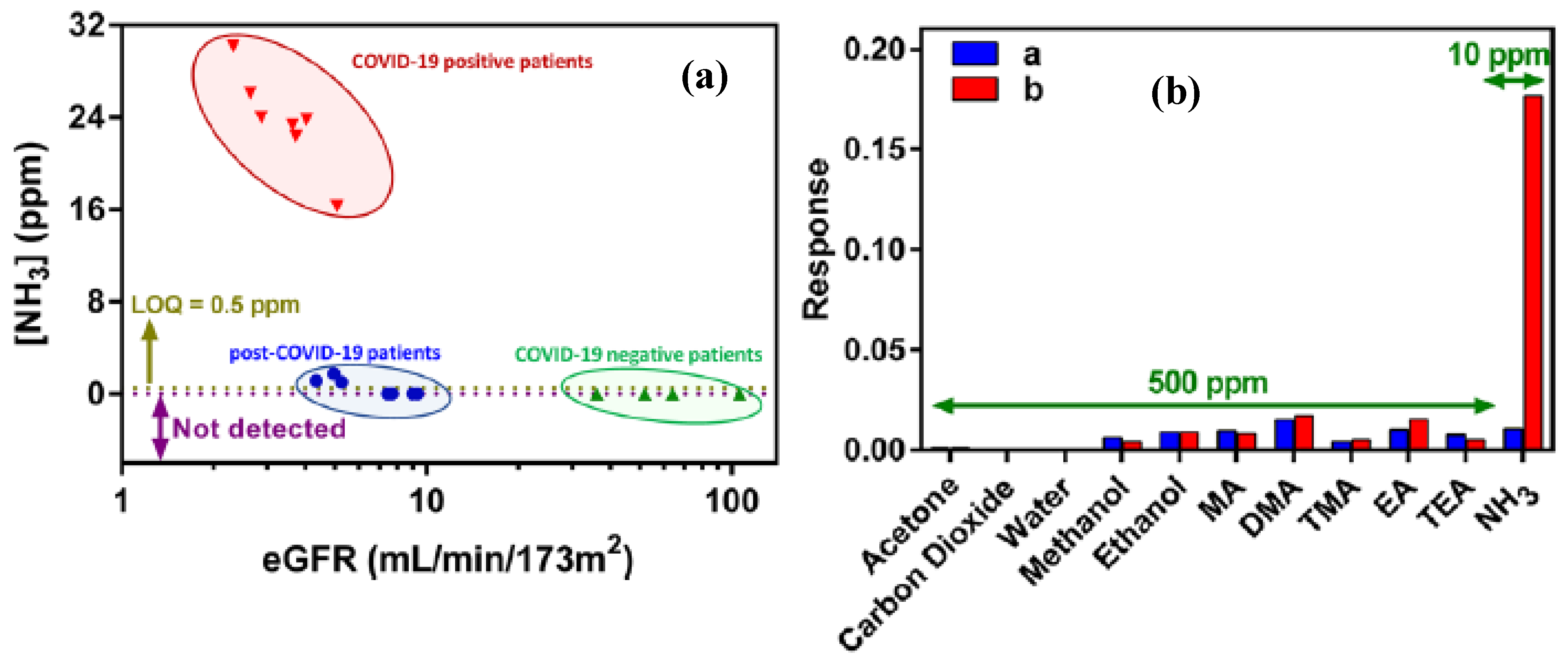

- Kamalabadi, M.; Ghoorchian, A.; Derakhshandeh, K.; Gholyaf, M.; Ravan, M. Design and Fabrication of a Gas Sensor Based on a Polypyrrole/Silver Nanoparticle Film for the Detection of Ammonia in Exhaled Breath of COVID-19 Patients Suffering from Acute Kidney Injury. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16290–16298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Morris, J.D.; Pan, J.; Cooke, E.A.; Sutaria, S.R.; Balcom, D.; Marimuthu, S.; Parrish, L.W.; Aliesky, H.; Huang, J.J.; et al. Detection of COVID-19 by quantitative analysis of carbonyl compounds in exhaled breath. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausinger, R.P. Metabolic versatility of prokaryotes for urea decomposition. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2520–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, S.S.; Khattar, D. Biochemistry, Ammonia. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bevc, S.; Mohorko, E.; Kolar, M.; Brglez, P.; Holobar, A.; Kniepeiss, D.; Podbregar, M.; Piko, N.; Hojs, N.; Knehtl, M.; et al. Measurement of breath ammonia for detection of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Nephrol. 2017, 88, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, R.; Wang, K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.; Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Ge, S.; Xu, G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, B.; Broza, Y.Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gui, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Multiplexed Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Array for Detection of COVID-19 in Exhaled Breath. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12125–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, L.R.; Goodman, W.; Patel, C.K.N. Correlation of breath ammonia with blood urea nitrogen and creatinine during hemodialysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4617–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manne, J.; Sukhorukov, O.; Jäger, W.; Tulip, J. Pulsed quantum cascade laser-based cavity ring-down spectroscopy for ammonia detection in breath. Appl. Opt. 2006, 45, 9230–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

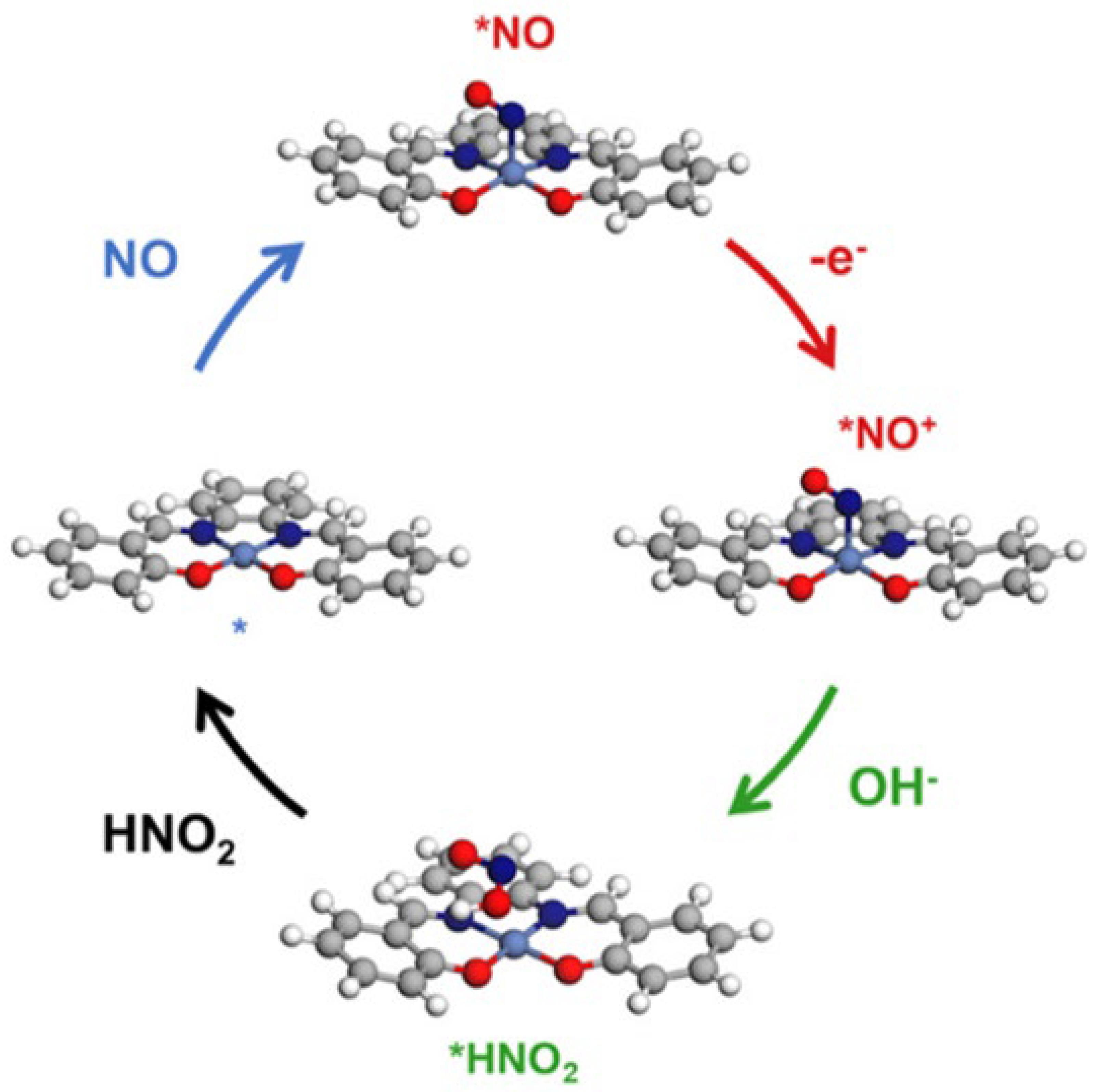

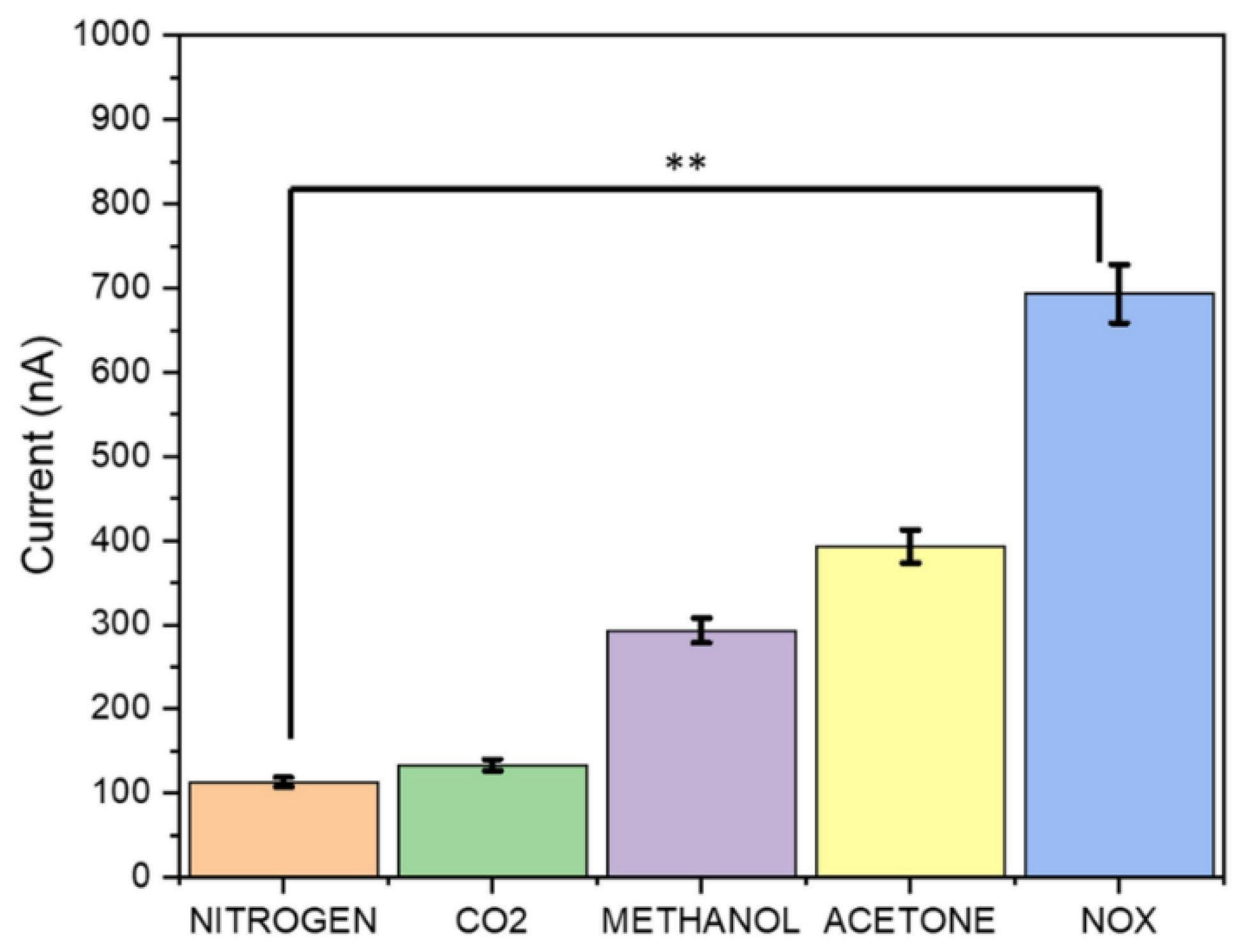

- Zhou, W.; Tan, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Sun, L.; Deng, W. Ultrasensitive NO Sensor Based on a Nickel Single-Atom Electrocatalyst for Preliminary Screening of COVID-19. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 3422–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, T.; Itoh, T.; Izu, N.; Shin, W. NO and NO2 sensing properties of WO3 and Co3O4 based gas sensors. Sensors 2013, 13, 12467–12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Yu, P.; Lin, Y.; Mao, J.; Mao, L. Single-atom Ni-N4 provides a robust cellular NO sensor. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, I.; Paul, A.; France, K.; Micklich, B.; Cardwell, B.; Micklich, C.; Prasad, S. E.Co.Tech-electrochemical handheld breathalyzer COVID sensing technology. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Miura, N.; Yamazoe, N. Study of WO3-based sensing materials for NH3 and NO detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2000, 66, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

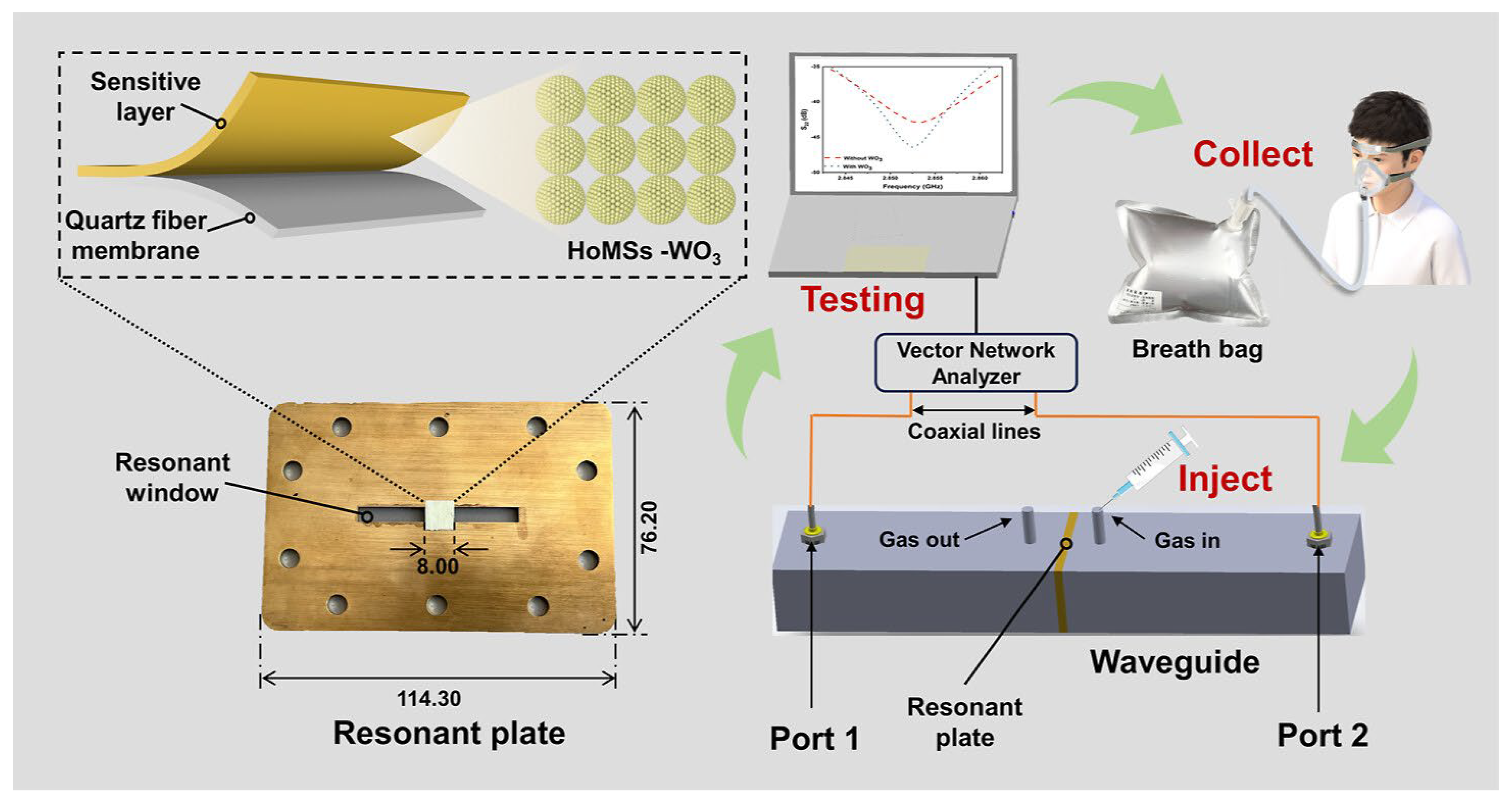

- Wang, R.; Ma, T.; Jin, Q.; Xu, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, X. Waveguide-Based Microwave Nitric Oxide Sensor for COVID-19 Screening: Mass Transfer Modulation Effect on Hollow Confined WO3 Structures. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 6051–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, M.C.; Stanacevic, M.; Bowman, A.S.; Gouma, P.I. Exhaled nitric oxide detection for diagnosis of COVID-19 in critically ill patients. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingangavkar, G.M.; Kadam, S.A.; Ma, Y.-R.; Sartale, S.D.; Mulik, R.N.; Patil, V.B. Intercalation of two-dimensional graphene oxide in WO3 nanoflowers for NO2 sensing. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2023, 34, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, N.; Bairagi, V.; Munot, M.; Gaikwad, K.; Jadhav, S. Automated COVID-19 Detection from Exhaled Human Breath Using CNN-CatBoost Ensemble Model. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2023, 7, 7005604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.D.; Arranz, D.; Peña, A.; Marín, P.; Horrillo, M.C.; de la Presa, P.; Matatagui, D. Real-time monitoring of breath biomarkers using magnonic wireless sensor based on magnetic nanoparticles. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2024, 43, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Zang, W.; Tabartehfarahani, A.; Lam, A.; Huang, X.; Sivakumar, A.D.; Thota, C.; Yang, S.; Dickson, R.P.; Sjoding, M.W.; et al. Portable Breath-Based Volatile Organic Compound Monitoring for the Detection of COVID-19 During the Circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant and the Transition to the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovusha, H.; Panigrahi, P.; Pal, Y.; Bae, H.; Park, M.; Son, S.-K.; Shiddiky, M.J.A.; Hussain, T.; Lee, H. Efficient detection of specific volatile organic compounds associated with COVID-19 using CrX2 (X = Se, Te) monolayers. FlatChem 2024, 43, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de León-Martínez, L.; Flores-Rangel, G.; Alcántara-Quintana, L.E.; Mizaikoff, B. A Review on Long COVID Screening: Challenges and Perspectives Focusing on Exhaled Breath Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 1564–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Response Time | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cost | Settings | Clinical Validation Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | RNA | ~10–100 copies/reaction | ≈1 h 30 min | 98.1–100% | 95.7–100% | expensive | Labs | extensively validated, globally approved | [4,12,25,26,27,28] |

| Immunoassay/(Antigen/Antibody) | Viral antigen/host antibodies | ~10–100 ng/mL | 30 min | 56.2% | 99.5% | Low cost | Point of care | Clinically validated, approved | [29,30,31,32,33,34] |

| Chest X-ray /CT Imaging | Lung abnormalities | N/A | Rapid | 44–98% | 25–96% | Moderate | Hospitals & Labs | Clinically validated for monitoring | [35,36,37,38] |

| Gas sensors for exhaled breath | VOCs and gases | ppm–ppb range | Rapid | 98.2% | 74.3% | moderate | portable | Limited pilot-level clinical validation | [15,17,24,39,40,41,42,43] |

| QCM biosensor | Viral particles | 40–210 pfu/mL | ≈5 min | 98.15% | 96.87% | Moderate | Research labs/pilot clinical | Early clinical validation, under evaluation | [44,45,46] |

| SERS biosensor | Spike protein/viral components | ≈300 nM | 5 min | 95% | 95% | Moderate–High | Lab validation | Research-stage validation, not yet approved | [47,48,49,50,51,52] |

| FET/BioFET | Viral proteins/RNA | pM–fM | >1 min | Ultra-sensitive | Ultra specific | Moderate–High | Lab/small-scale clinical | Limited clinical validation, development ongoing | [53,54,55] |

| CRISPR-Cas Diagnostics | Viral RNA | ~10 copies/µL | ~15–60 min | 94% | 98% | Moderate | Point-of-care/low resource | Clinically validated, several approved assays | [18,56,57,58,59,60,61] |

| CRISPR-MCDA one-pot | Viral RNA | ~10 copies/µL | 30–45 min | 96–98% | 100% | Moderate | Lab/near POC | Pilot-level clinical validation, limited regulatory approval | [61,62] |

| Wearable Sensor Systems | Physiological biomarkers | N/A | Continuous | 36.5–100% | 73–95.3% | Low-Moderate | Remote/consumer | Clinically studied, limited diagnostic approval | [63,64,65,66] |

| Sensor | Gas/VOC | Detection Limit | Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel based SAC | FeNO | 1.8 nM | - | [101] |

| [EMIM]BF4 | NO | 50 ppb | 91.36% | [104] |

| HoMSs-WO3 | NO | 2.52 ppb | - | [106] |

| WO3 | NO | - | 85% | [107] |

| Au-IDEs/S-PPys/AgNP | NH3 | 0.12 ppm | - | [93] |

| CNN-CatBoost model | Acetone Ethanol Methanol Isoproponol | - | 98.97–99.04% | [109] |

| Fe3O4 | Acetone | 0.75 ppm | - | [110] |

| Oxide semiconductor | VOCs | - | 90–95% | [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fatima, M.; Fatima, M.; Abbas, N.; Park, P.-G. Opportunities and Challenges in Gas Sensor Technologies for Accurate Detection of COVID-19. Biosensors 2025, 15, 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120792

Fatima M, Fatima M, Abbas N, Park P-G. Opportunities and Challenges in Gas Sensor Technologies for Accurate Detection of COVID-19. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120792

Chicago/Turabian StyleFatima, Masoom, Munazza Fatima, Naseem Abbas, and Pil-Gu Park. 2025. "Opportunities and Challenges in Gas Sensor Technologies for Accurate Detection of COVID-19" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120792

APA StyleFatima, M., Fatima, M., Abbas, N., & Park, P.-G. (2025). Opportunities and Challenges in Gas Sensor Technologies for Accurate Detection of COVID-19. Biosensors, 15(12), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120792