Synthesis of a Zinc Oxide Nanoflower Photocatalyst from Sea Buckthorn Fruit for Degradation of Industrial Dyes in Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Sea Buckthorn Fruit Extract

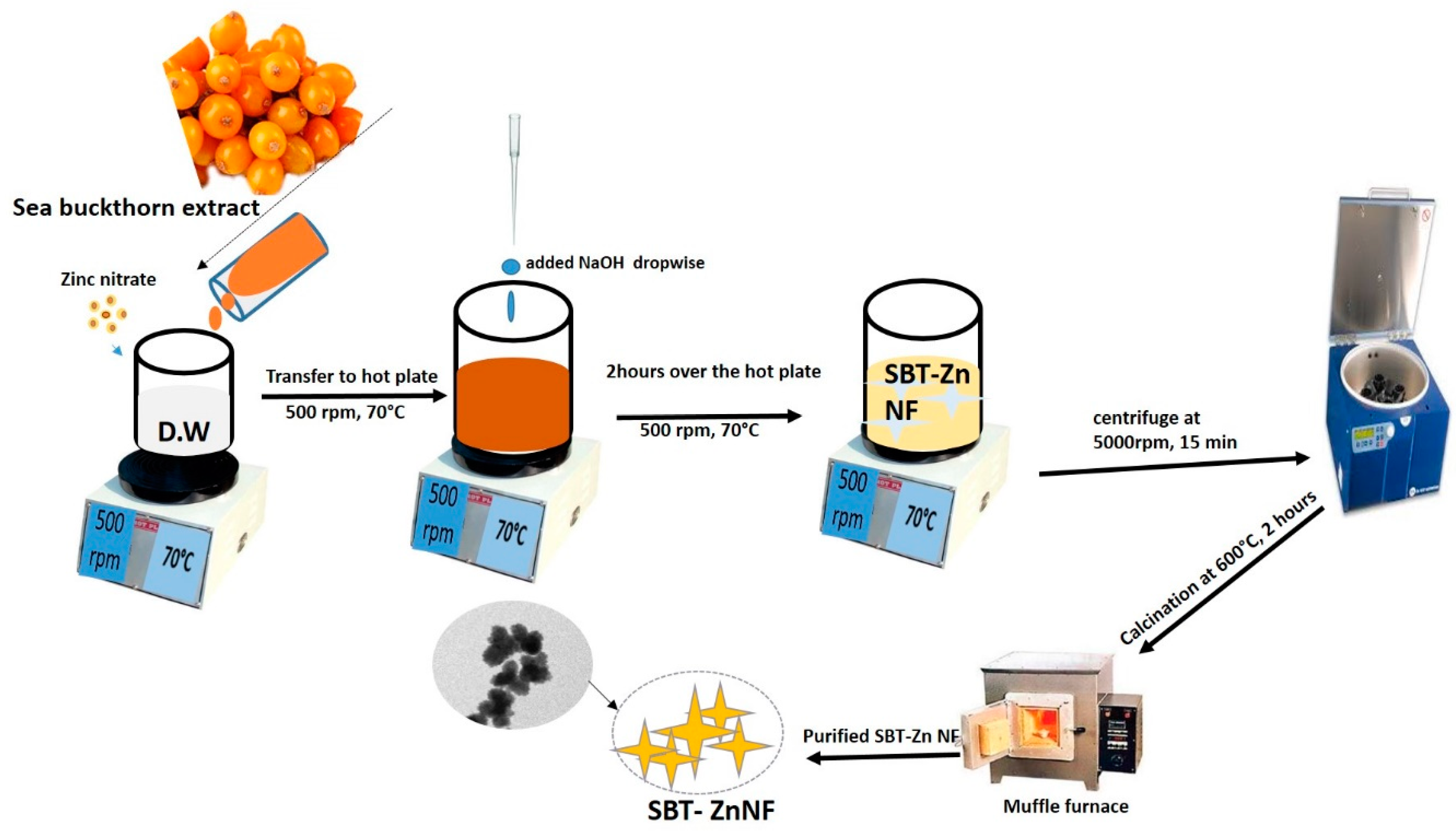

2.3. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoflowers from Sea Buckthorn Fruit Extract

2.4. Characterization of SBT-ZnO/NFs

2.5. Photocatalytic Activity of SBT-ZnO/NFs

3. Results and Discussion

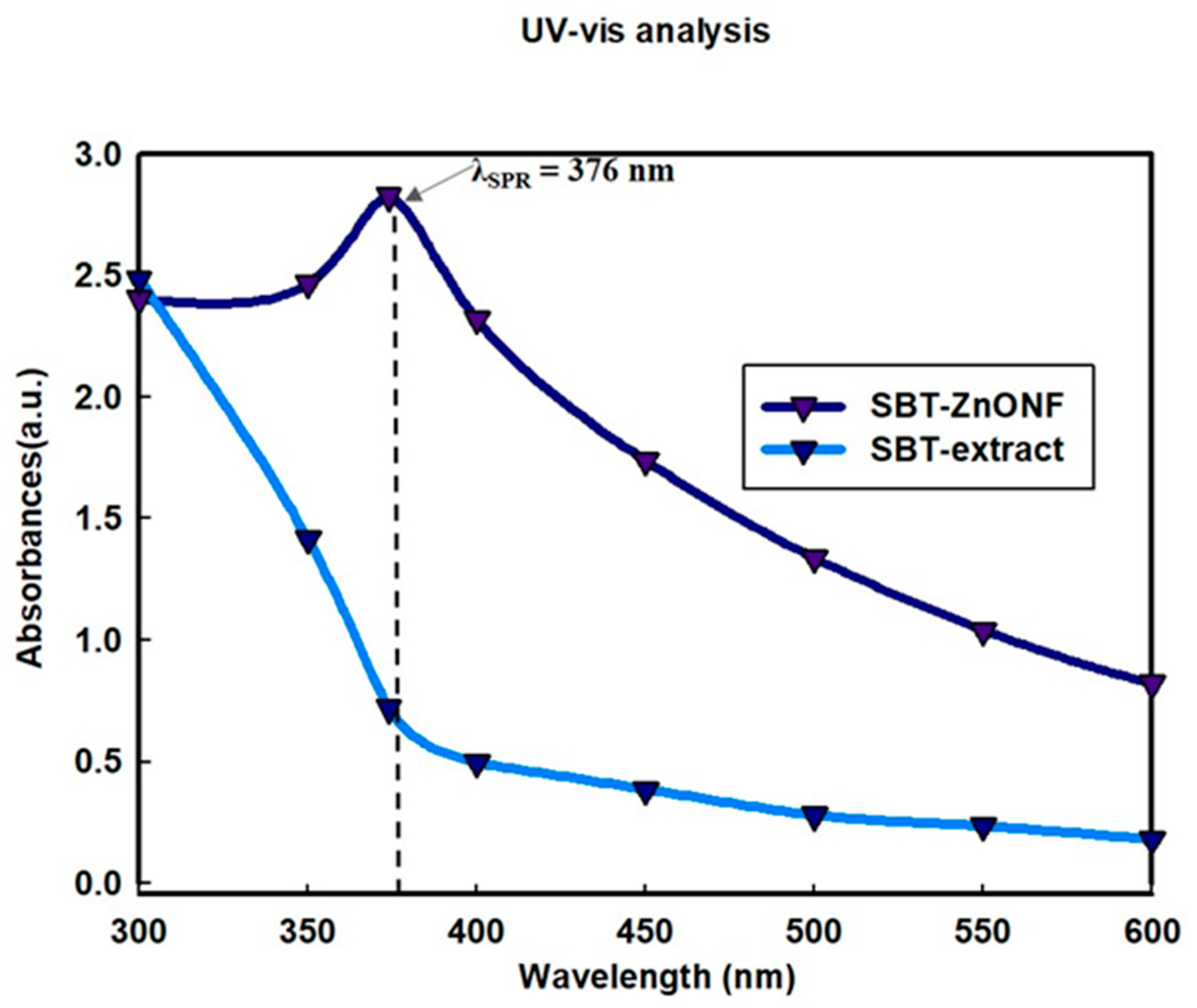

3.1. UV-Visible Spectrophotometer Analysis

3.2. FE-TEM Analysis

3.3. XRD Analysis

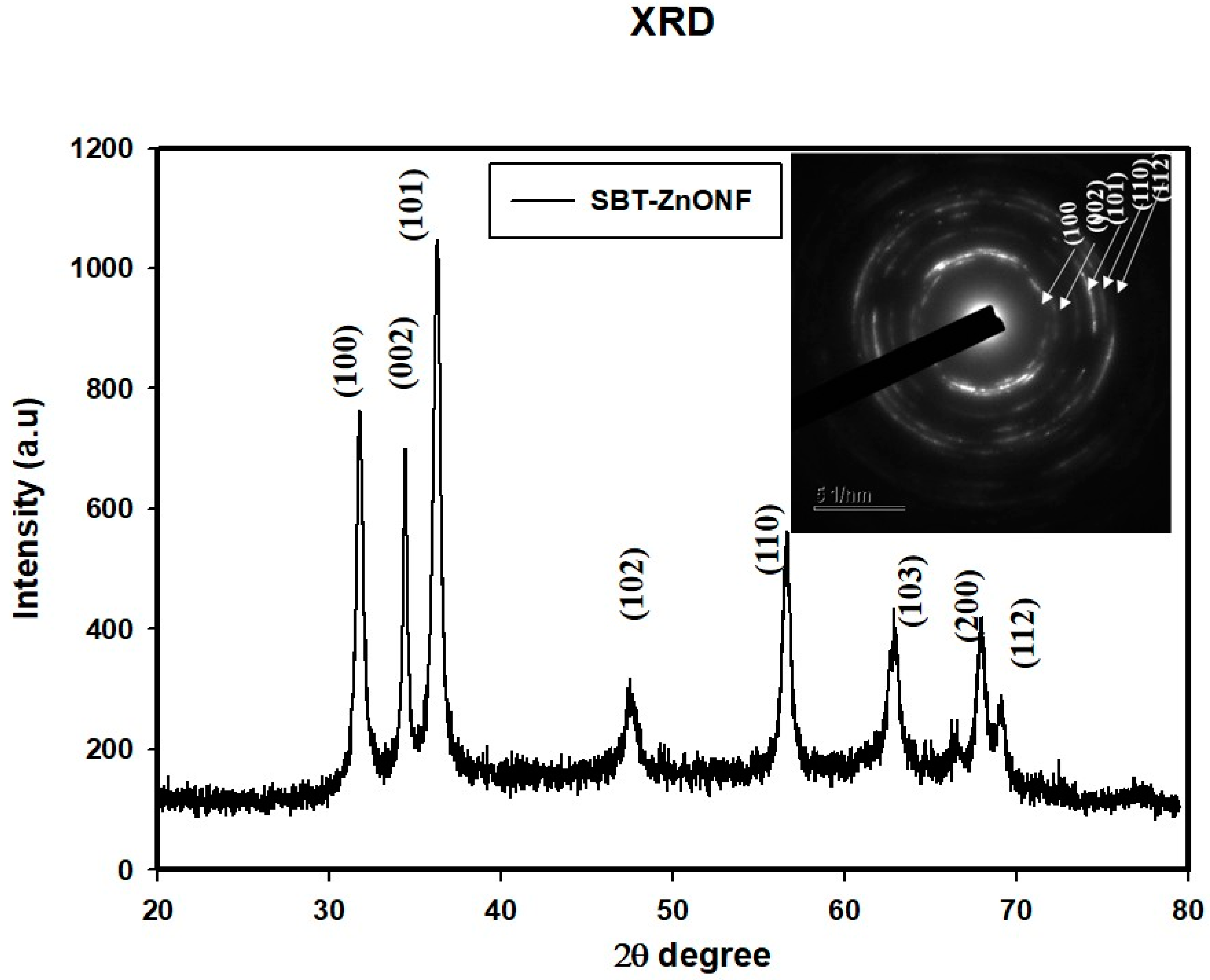

3.4. FT-IR Analysis

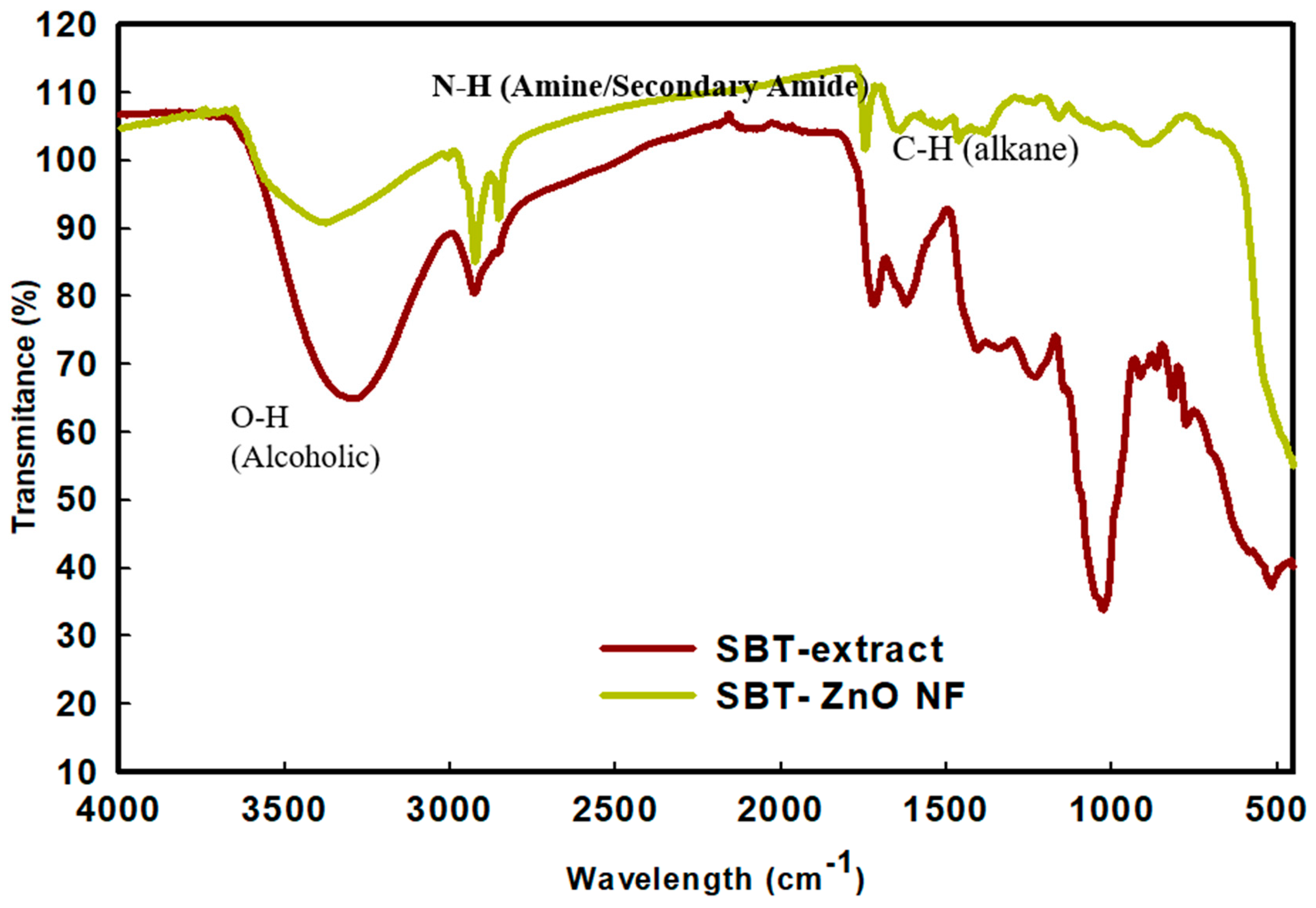

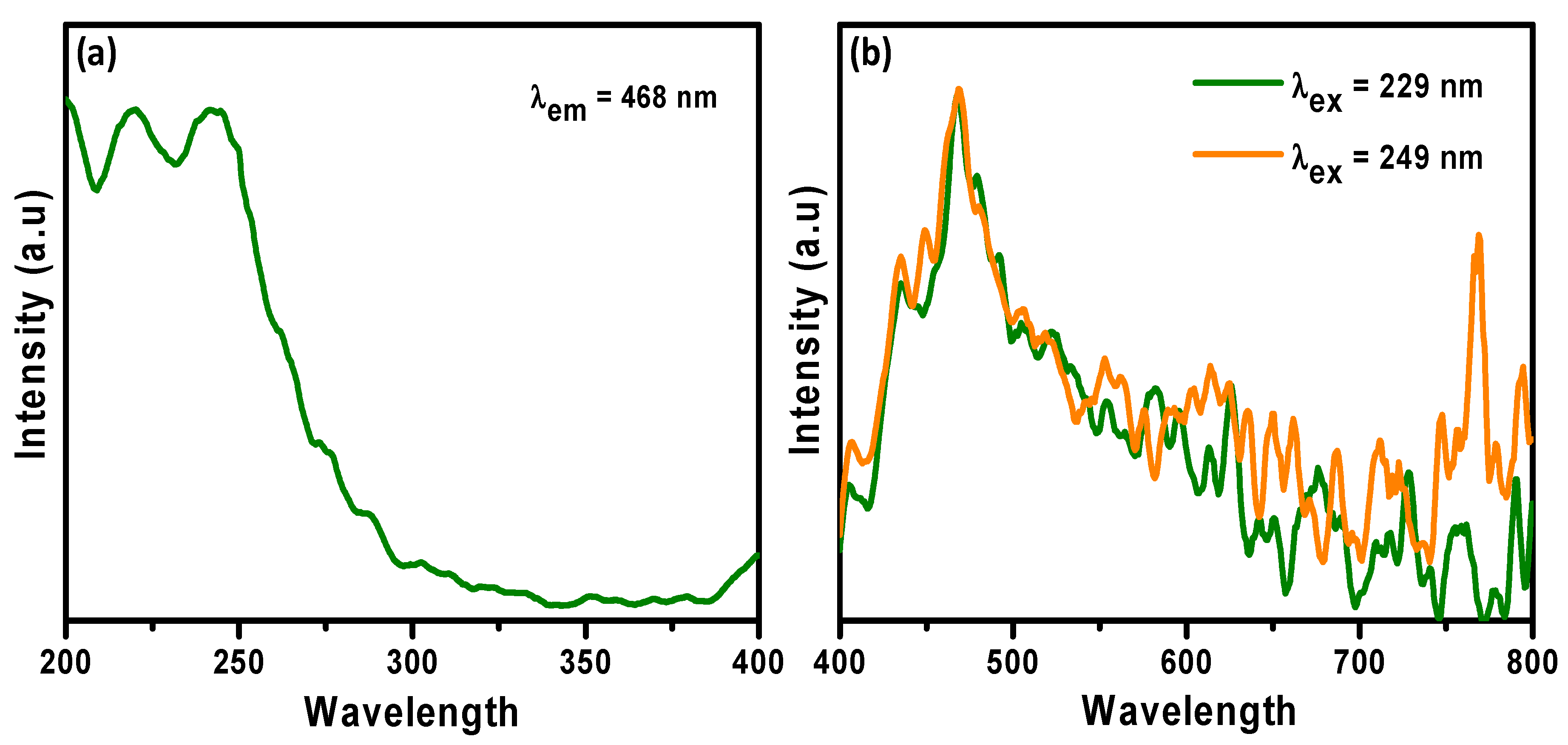

3.5. Photoluminescence

3.6. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Analysis

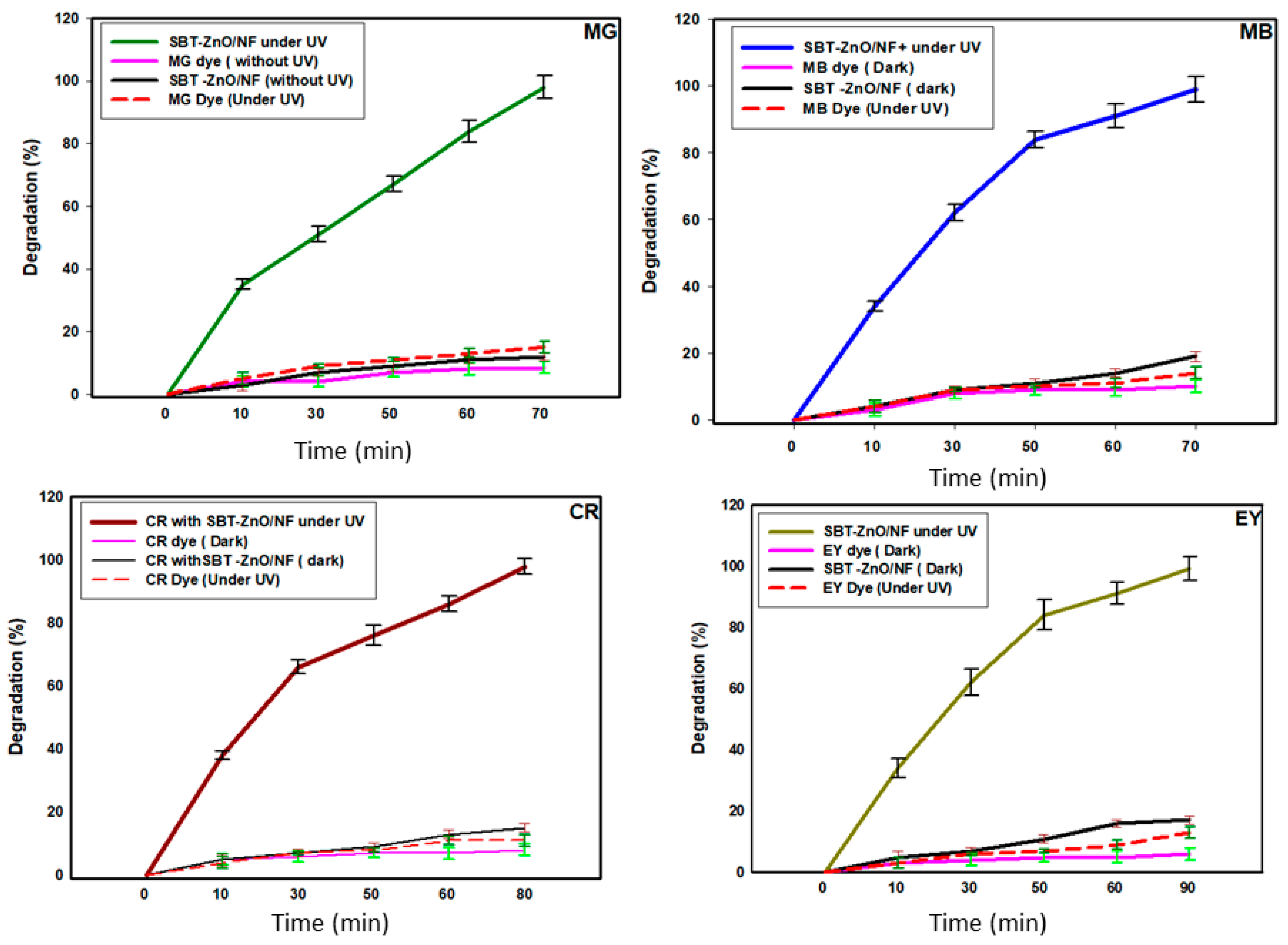

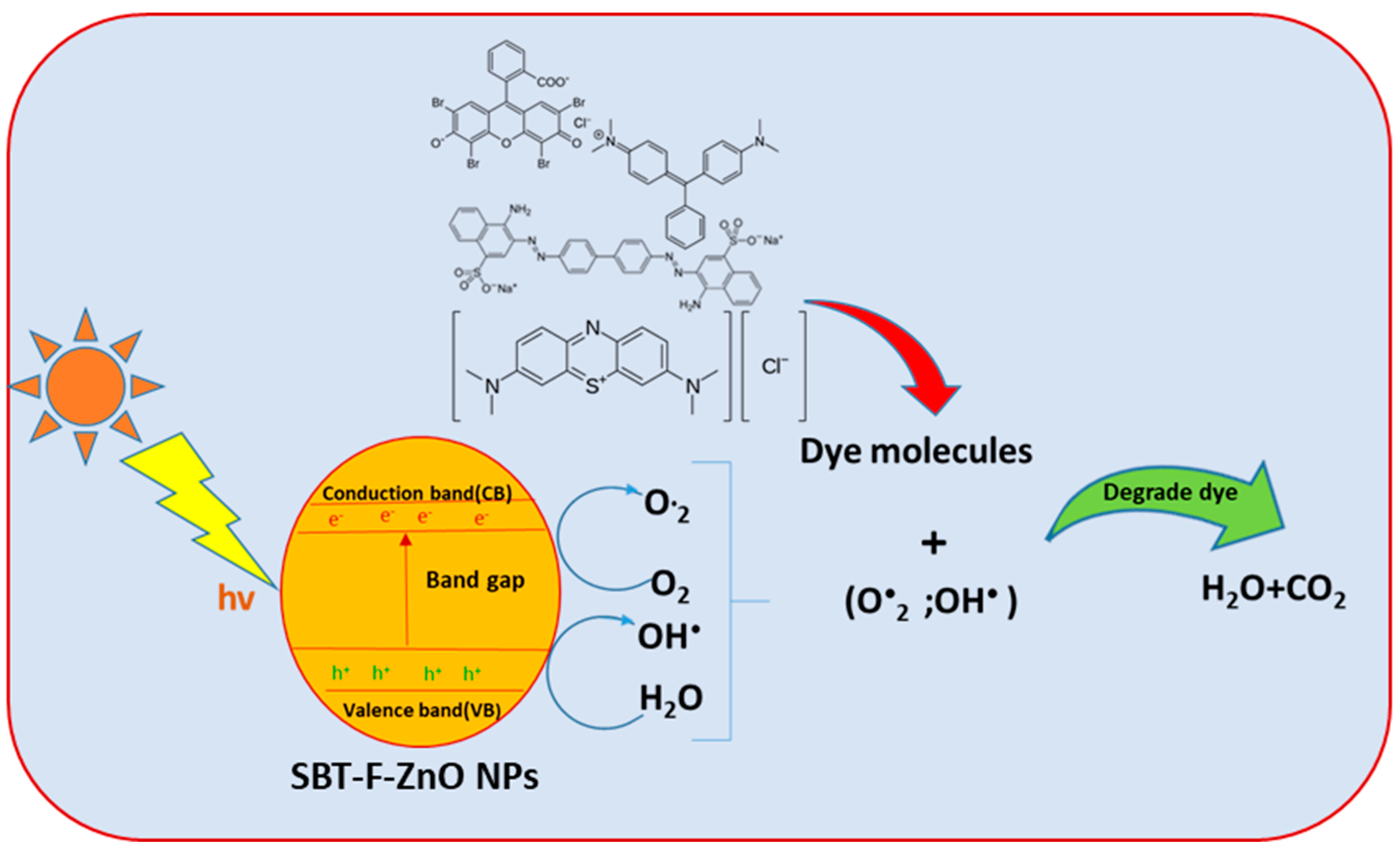

3.7. Photocatalytic Activity of SBT-ZnO/NF under UV Illumination

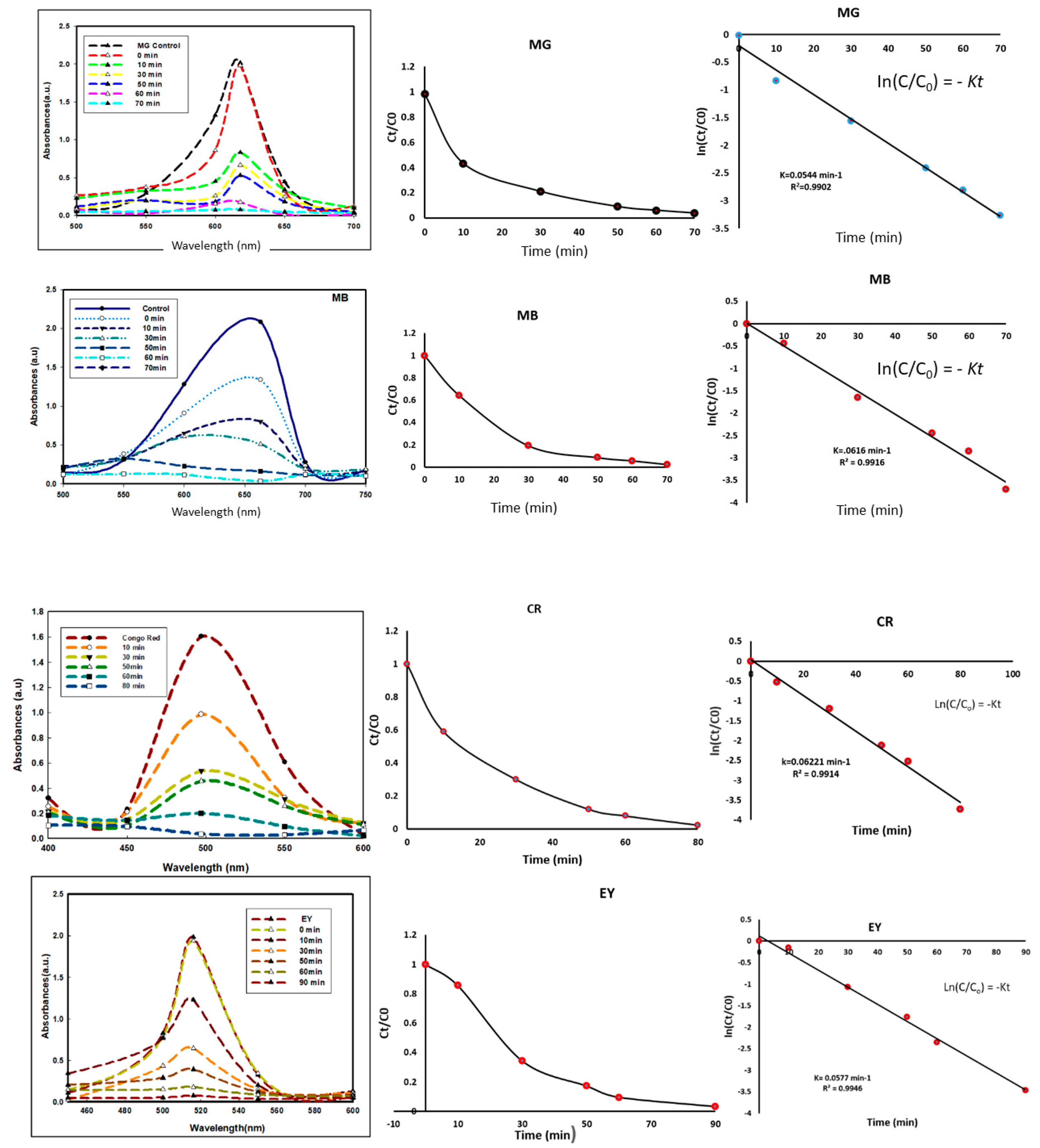

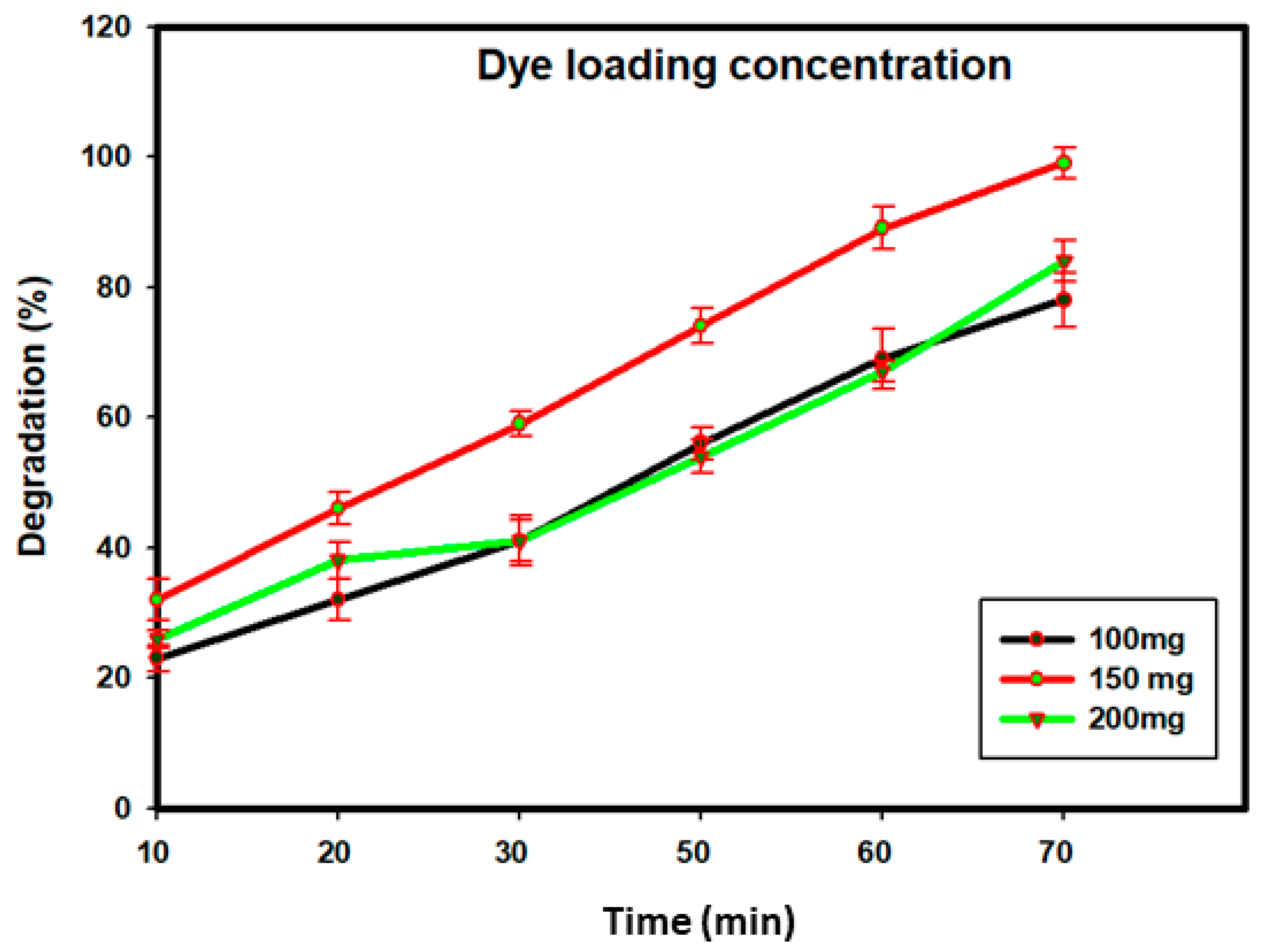

3.8. Degradation

3.9. Catalyst (SBT-ZnO/NF) Reusability

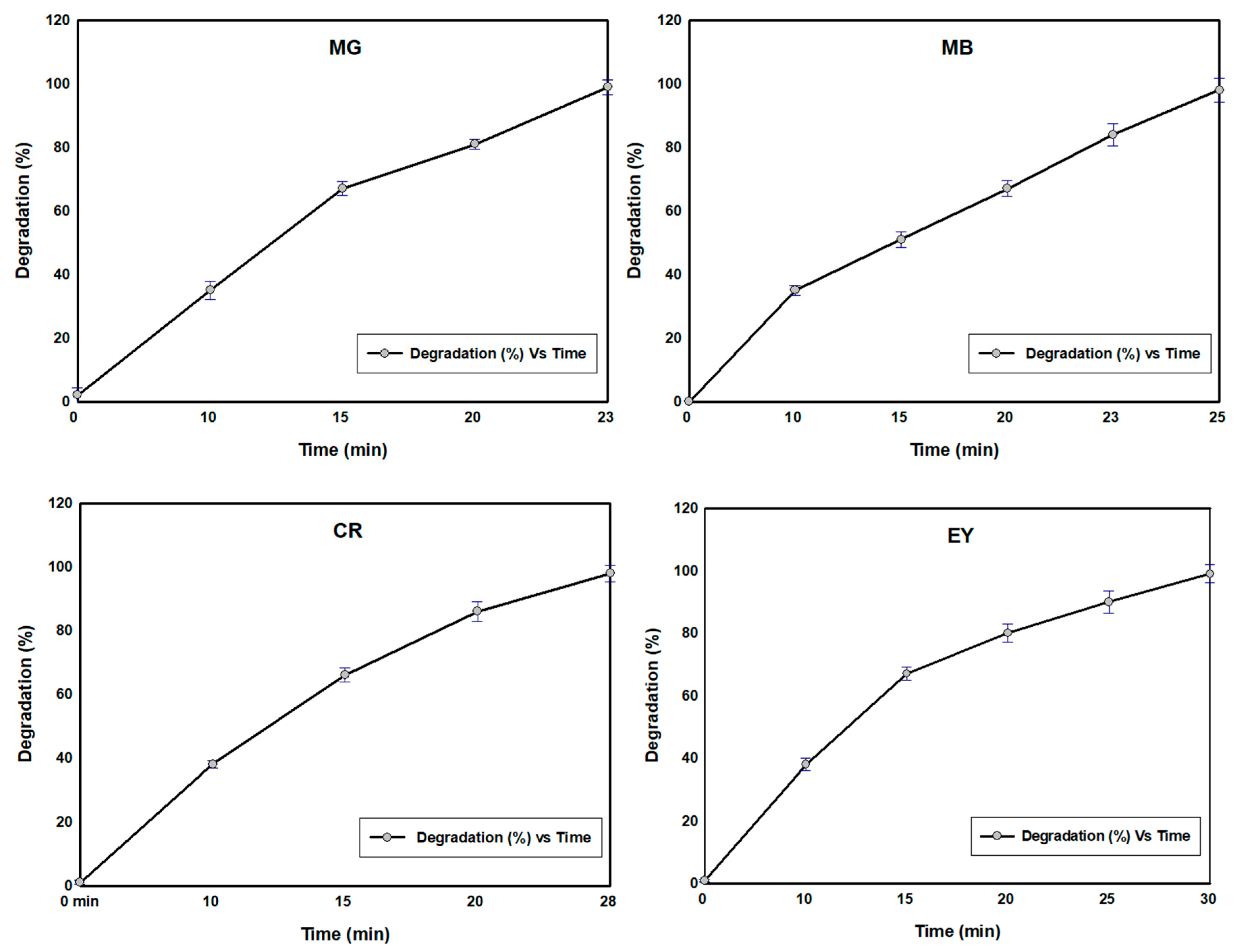

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, M.; Mehta, A.; Mishra, A.; Singh, J.; Rawat, M.; Basu, S. Biosynthesis of tin oxide nanoparticles using Psidium Guajava leave extract for photocatalytic dye degradation under sunlight. Mater. Lett. 2018, 215, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Chaudhary, G.R.; Mehta, S. Comparative study of catalytic activity of ZrO2 nanoparticles for sonocatalytic and photocatalytic degradation of cationic and anionic dyes. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 280, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.V.; Chandrasekhar, K. Solid-phase microbial fuel cell (SMFC) for harnessing bioelectricity from composite food waste fermentation: Influence of electrode assembly and buffering capacity. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7077–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singh, N.; Afzal, S.; Singh, T.; Hussain, I. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: A review of their biological synthesis, antimicrobial activity, uptake, translocation and biotransformation in plants. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.P.; Venugopal, A.; Subrahmanyam, M. Hydroxyapatite photocatalytic degradation of calmagite (an azo dye) in aqueous suspension. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 69, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, T.; Wu, K.; Oikawa, K.; Hidaka, H.; Serpone, N. Photo assisted degradation of dye pollutants. 3. Degradation of the cationic dye rhodamine B in aqueous anionic surfactant/TiO2 dispersions under visible light irradiation: Evidence for the need of substrate adsorption on TiO2 particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2394–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jincai, Z.; Taixing, W.; Kaiqun, W. Degradation of the cationic dye rhodamine B in aqueous anionic surfactant/TiO2 dispersions under visible light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2394–2400. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, R.; Dutta, J. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes with manganese-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 156, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Shah, A.A.; Almani, K.F.; Tahira, A.; Chalangar, S.E.; Chandio, A.D.; Nur, O.; Willander, M.; Ibupoto, Z.H. Efficient photocatalysts based on silver doped ZnO nanorods for the photodegradation of methyl orange. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 23289–23297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemingui, H.; Missaoui, T.; Mzali, J.C.; Yildiz, T.; Konyar, M.; Smiri, M.; Saiidi, N.; Hafane, A.; Yatmaz, H. Facile green synthesis of Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs): Antibacterial and photocatalytic activities. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 1050b4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjaalie, L.; Himmetoglu, B.; Weston, L.; Janotti, A.; van de Walle, C. Oxide interfaces for novel electronic applications. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 025005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Pathakoti, K.; Hwang, H.-M. Green Synthesis of Titanium Dioxide and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Usage for Antimicrobial Applications and Environmental Remediation, in Green Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Nanoparticles; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 223–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zeb, A. Chemical and nutritional constituents of sea buckthorn juice. Pak. J. Nutr. 2004, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Yang, B.; Peippo, P.; Tahvonen, R.; Pan, R. Triacylglycerols, Glycerophospholipids, Tocopherols, and Tocotrienols in Berries and Seeds of Two Subspecies (ssp. sinensis and mongolica) of Sea Buckthorn (Hippopha> ë rhamnoides). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3004–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christaki, E. Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Sea Buckthorn): A potential source of nutraceuticals. Food Public Health 2012, 2, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ohlander, M.; Jeppsson, N.; Björk, L.; Trajkovski, V. Changes in antioxidant effects and their relationship to phytonutrients in fruits of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) during maturation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Kallio, H. Composition and physiological effects of sea buckthorn (Hippophae) lipids. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryakumar, G.; Gupta, A. Medicinal and therapeutic potential of Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, D.; Blanchette, M.; Barrette, S.; Moghrabi, A.; Beliveau, R. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation and suppression of TNF-induced activation of NFκB by edible berry juice. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27, 937–948. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed, A.; Kumar, P. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles by co-precipitation method at room temperature. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2016, 8, 624–628. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, J.; Wang, D.; Kim, Y.-J.; Ahn, S.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Wang, C.; Yang, D.C. Biosynthesis, characterization, and bioactivities evaluation of silver and gold nanoparticles mediated by the roots of Chinese herbal Angelica pubescens Maxim. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Z.E.J.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Markus, J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kang, H.M.; Abbai, R.; Seo, K.H.; Wang, D.; Soshnikova, V.; Yang, D.C. Ginseng-berry-mediated gold and silver nanoparticle synthesis and evaluation of their in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity effects on human dermal fibroblast and murine melanoma skin cell lines. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.H.; Soshnikova, V.; Markus, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.C.; Singh, P.; Castro-Aceituno, V.; Ahn, S.; Kim, D.H.; Shim, Y.J. Biosynthesized gold and silver nanoparticles by aqueous fruit extract of Chaenomeles sinensis and screening of their biomedical activities. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Sáez, M.; Jaramillo, L.; Saravanan, R.; Benito, N.; Pabón, E.; Mosquera, E.; Gracia, F. Notable photocatalytic activity of TiO2-polyethylene nanocomposites for visible light degradation of organic pollutants. Express Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 899–909. [Google Scholar]

- Navaneethan, M.; Mani, G.K.; Ponnusamy, S.; Tsuchiya, K.; Muthamizhchelvan, C.; Kawasaki, S.; Hayakawa, Y. Influence of Al doping on the structural, morphological, optical, and gas sensing properties of ZnO nanorods. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 698, 555–564. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, P.; Giuseppe, M.; Sapia, M.; Valentina, P.; Ezio, R.; Danilo, S.; Domenico, P. Photocatalytic oxidation of organic micro-pollutants: Pilot plant investigation and mechanistic aspects of the degradation reaction. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2016, 203, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Petrella, A.; Spasiano, D.; Cosma, P.; Rizzi, V.; Race, M. Evaluation of the hydraulic and hydrodynamic parameters influencing photo-catalytic degradation of bio-persistent pollutants in a pilot plant. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2019, 206, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Ashokkumar, S.; Marthandam, R.P.; Jayachandiran, J.; Khatiwada, C.P.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Raman, R.G.; Swaminathan, M. Eco-friendly preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Tabernaemontana divaricata and its photocatalytic and antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 181, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YShim, J.; Soshnikova, V.; Anandapadmanaban, G.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Perez, Z.E.J.; Markus, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Castro-Aceituno, V.; Yang, D.C. Zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by Suaeda japonica Makino and their photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Optik 2019, 182, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Batjikh, I.; Hurh, J.; Han, Y.; Ali, H.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Ling, C.; Ahn, J.C.; Yang, D.C. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles from bark extract of Kalopanax septemlobus. Optik 2019, 182, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, E.J.; Anandapadmanaban, G.; Chokkalingam, M.; Li, J.F.; Markus, J.; Soshnikova, V.; Perez, Z.; Yang, D.-C. Cationic and anionic dye degradation activity of Zinc oxide nanoparticles from Hippophae rhamnoides leave as potential water treatment resource. Optik 2019, 181, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, R.E.; Anandapadmanaban, G.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Yang, D.-C. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from immature fruits of Rubus coreanus and its catalytic activity for degradation of industrial dye. Optik 2018, 172, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, A.R.; Garvasis, J.; Oruvil, S.K.; Joseph, A. Bio-inspired green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Abelmoschus esculentus mucilage and selective degradation of cationic dye pollutants. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 127, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, N.; Salari, D.; Khataee, A. Photocatalytic degradation of azo dye acid red 14 in the water on ZnO as an alternative catalyst to TiO2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2004, 162, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

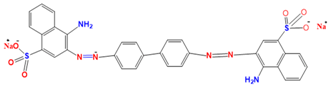

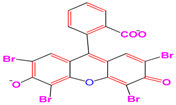

| Structures of Dye Molecules | Maximum Intensity (nm) |

|---|---|

Malachite green | 618 nm |

Methylene blue | 663 nm |

Congo red | 497 nm |

Eosin Y | 517 nm |

| Peak No | Peak Position at (2θ) | d Spacing Value (A°) | FWHM Value (2θ) | Size (nm) | Average (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 31.82 | d = 2.81163 | 0.5885 | 15.56 | |

| 002 | 34.412 | d = 2.60226 | 0.3923 | 21.07 | |

| 101 | 36.272 | d = 2.47333 | 0.5654 | 14.72 | |

| 102 | 47.552 | d = 1.91472 | 1.2555 | 6.67 | 17.12 |

| 110 | 56.613 | d = 1.90877 | 0.7454 | 11.63 | |

| 103 | 62.883 | d = 1.62367 | 1.079 | 8.38 | |

| 112 | 67.979 | d = 1.61797 | 1.4749 | 6.32 |

| Plant Extract | Dye | Dye Concentration | Catalyst Loaded | Degradation (%) | Time (min) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tabernaemontana divaricata | Methylene blue | 5 mg/L | 100 mg | 90% | 90 min | [28] |

| Suaeda japonica Makino | Methylene blue | 10 mg/L | 50 mg | 54% | 180min | [29] |

| Kalopanax septemlobus | Methylene blue | 10 mg/L | 150 mg | 97% | 30 min | [30] |

| Hippophae rhamnoides leaves | Malachite green | 10 mg/L | 150 mg | 89% | 180 min | [31] |

| Rubus coreanus | Malachite green | 10 mg/L | 50 mg | 90% | 240 min | [32] |

| Abelmoschus esculentus | Methylene blue | 9.5 mg/L | 125 mg | 100% | 60 min | [33] |

| Hippophoe Rhamnoides fruits | Methylene blue | 15 mg/L | 150 mg | 99% | 70 min | This work |

| Hippophoe Rhamnoides fruits | Malachite green | 15 mg/L | 150 mg | 100% | 70 min | This work |

| Hippophoe Rhamnoides fruits | Congo red | 15 mg/L | 150 mg | 99% | 80 min | This work |

| Hippophoe Rhamnoides fruits | Eosin Y | 15 mg/L | 150 mg | 100% | 90 min | This work |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rupa, E.J.; Kaliraj, L.; Abid, S.; Yang, D.-C.; Jung, S.-K. Synthesis of a Zinc Oxide Nanoflower Photocatalyst from Sea Buckthorn Fruit for Degradation of Industrial Dyes in Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9121692

Rupa EJ, Kaliraj L, Abid S, Yang D-C, Jung S-K. Synthesis of a Zinc Oxide Nanoflower Photocatalyst from Sea Buckthorn Fruit for Degradation of Industrial Dyes in Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials. 2019; 9(12):1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9121692

Chicago/Turabian StyleRupa, Esrat Jahan, Lalitha Kaliraj, Suleman Abid, Deok-Chun Yang, and Seok-Kyu Jung. 2019. "Synthesis of a Zinc Oxide Nanoflower Photocatalyst from Sea Buckthorn Fruit for Degradation of Industrial Dyes in Wastewater Treatment" Nanomaterials 9, no. 12: 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9121692

APA StyleRupa, E. J., Kaliraj, L., Abid, S., Yang, D.-C., & Jung, S.-K. (2019). Synthesis of a Zinc Oxide Nanoflower Photocatalyst from Sea Buckthorn Fruit for Degradation of Industrial Dyes in Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials, 9(12), 1692. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9121692