Tailoring Ge Nanocrystals via Ag-Catalyzed Chemical Vapor Deposition to Enhance the Performance of Non-Volatile Memory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

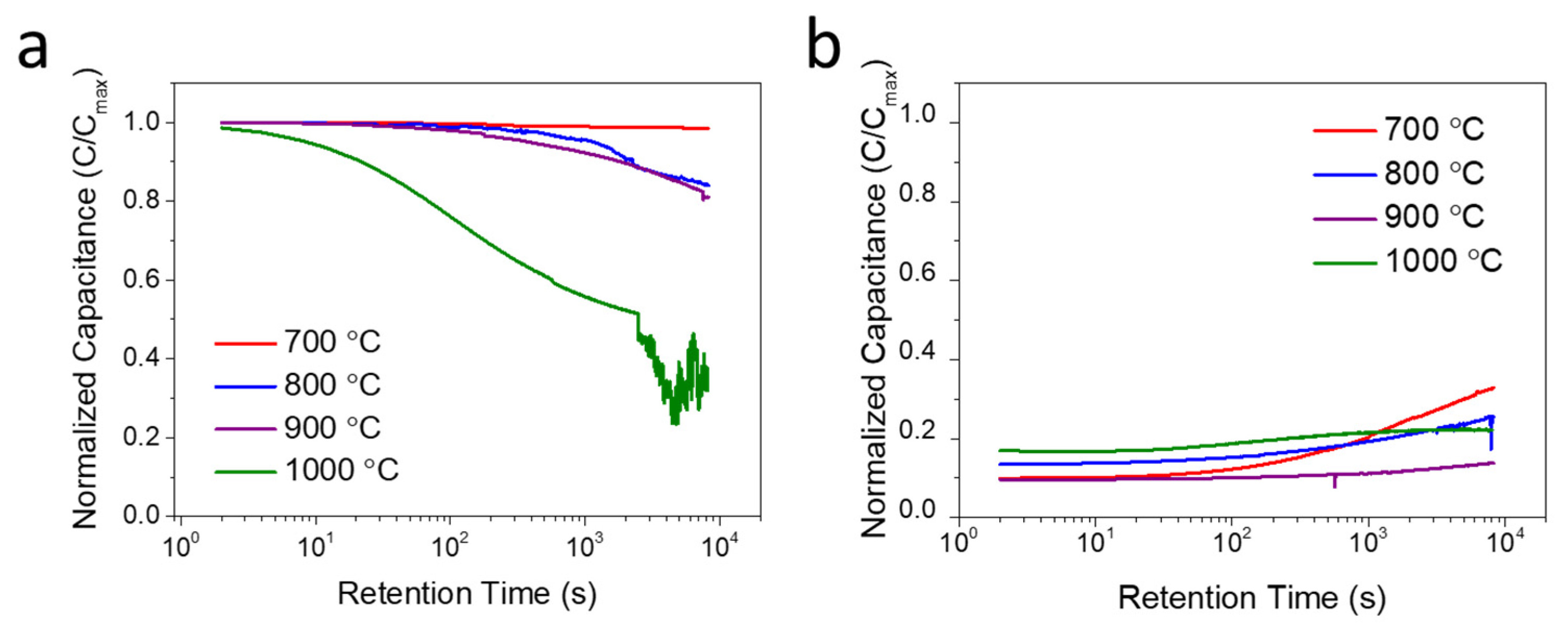

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chim, W.K. Germanium Nanocrystal Non-Volatile Memory Devices: Fabrication, Charge Storage Mechanism and Characterization. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 4195–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Park, S.; Kim, S. Quantum Dots for Resistive Switching Memory and Artificial Synapse. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-Y.; Lin, J.-C.; Hwu, J.-G. Enhanced Coupling Current in Center MIS Tunnel Diode by Effective Control of the Edge Trapping in Ring with Al2O3/SiO2 Gate Stack. Appl. Phys. A 2024, 130, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Ma, Z.; Yu, X.; Chen, T.; Zhou, C.; Li, W.; Chen, K.; Xu, J.; Xu, L. Controlling the Carrier Injection Efficiency in 3D Nanocrystalline Silicon Floating Gate Memory by Novel Design of Control Layer. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenizi, M.A.; Aouassa, M.; Bouabdellaoui, M.; Saron, K.M.A.; Aladim, A.K.; Ibrahim, M.; Berbezier, I. Electrical and Dielectric Characterization of Ge Quantum Dots Embedded in MIS Structure (AuPd/SiO2:Ge QDs/n-Si) Grown by MBE. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 685, 415962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-C.; Jian, F.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Tsai, Y.-T. Developments in Nanocrystal Memory. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilse, K.; Schneider, T.; Ziegler, J.; Sprafke, A.; Wehrspohn, R.B. Integrated Low-Temperature Process for the Fabrication of Amorphous Si Nanoparticles Embedded in Al2O3 for Non-Volatile Memory Application: Integrated Low-Temperature Process for the Fabrication of Amorphous Si NPs. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2016, 213, 2446–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.Y.; Zhou, G.D.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.H.; Dai, J.Y. Memory Characteristics and Tunneling Mechanism of Ag Nanocrystal Embedded HfAlOx Films on Si83Ge17/Si Substrate. Thin Solid Film. 2014, 562, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, B.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Li, S.; Li, P. Memory Characteristics and Tunneling Mechanism of Pt Nano-Crystals Embedded in HfAlOx Films for Nonvolatile Flash Memory Devices. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2015, 15, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavarache, I.; Cojocaru, O.; Maraloiu, V.A.; Teodorescu, V.S.; Stoica, T.; Ciurea, M.L. Effects of Ge-Related Storage Centers Formation in Al2O3 Enhancing the Performance of Floating Gate Memories. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 542, 148702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.J.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.W.; Hu, D.; Zhao, Y.G. Improved Memory Characteristics of Charge Trap Memory by Employing Double Layered ZrO2 Nanocrystals and Inserted Al2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 044502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Mondal, S.; Rakshit, A.; Bose, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Chakraborty, S. Size and Density Controlled Ag Nanocluster Embedded MOS Structure for Memory Applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017, 63, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, P.; Sun, B.; Gao, Q. Silver-Insertion Induced Improvements in Dielectric Characteristics of the Hf-Based Film. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 575, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Rana, F.; Hanafi, H.; Hartstein, A.; Crabbé, E.F.; Chan, K. A Silicon Nanocrystals Based Memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 1377–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-R.; Chang, T.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Chang, C.-Y. Formation and Nonvolatile Memory Application of Ge Nanocrystals by Using Internal Competition Reaction of Si1.33Ge0.67 and Si2.67Ge1.33 Layers. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2009, 8, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Saito, K.; Ishikuro, H.; Hiramoto, T. Effects of Traps on Charge Storage Characteristics in Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Memory Structures Based on Silicon Nanocrystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 84, 2358–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehninger, D.; Beyer, J.; Heitmann, J. A Review on Ge Nanocrystals Embedded in SiO2 and High-k Dielectrics. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2018, 215, 1701028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slav, A.; Palade, C.; Lepadatu, A.M.; Ciurea, M.L.; Teodorescu, V.S.; Lazanu, S.; Maraloiu, A.V.; Logofatu, C.; Braic, M.; Kiss, A. How Morphology Determines the Charge Storage Properties of Ge Nanocrystals in HfO2. Scr. Mater. 2016, 113, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakis, P.; Mouti, A.; Bonafos, C.; Schamm, S.; Ben Assayag, G.; Ioannou-Sougleridis, V.; Schmidt, B.; Becker, J.; Normand, P. Ultra-Low-Energy Ion-Beam-Synthesis of Ge Nanocrystals in Thin ALD Al2O3 Layers for Memory Applications. Microelectron. Eng. 2009, 86, 1838–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoun, M.; Busseret, C.; Poncet, A.; Souifi, A.; Baron, T.; Gautier, E. Electronic Properties of Ge Nanocrystals for Non Volatile Memory Applications. Solid-State Electron. 2006, 50, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluguri, R.; Das, S.; Singha, R.K.; Ray, S.K. Size Dependent Charge Storage Characteristics of MBE Grown Ge Nanocrystals on Surface Oxidized Si. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2013, 13, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Singha, R.K.; Dhar, A.; Ray, S.K.; Anopchenko, A.; Daldosso, N.; Pavesi, L. Electroluminescence and Charge Storage Characteristics of Quantum Confined Germanium Nanocrystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 024310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakis, P.; Ioannou-Sougleridis, V.; Normand, P.; Bonafos, C.; Schamm, S.; Mouti, A.; Schmidt, B.; Becker, J. Formation of Ge Nanocrystals in High-k Dielectric Layers for Memory Applications. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 2010, 1250, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoun, M.; Souifi, A.; Baron, T.; Mazen, F. Electrical Study of Ge-Nanocrystal-Based Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Structures for p-Type Nonvolatile Memory Applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 5079–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Endoh, T.; Fukuda, H.; Nomura, S.; Sakai, A.; Ueda, Y. Ge Nanocrystals in SiO2 Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 1195–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolobov, A.V. Raman Scattering from Ge Nanostructures Grown on Si Substrates: Power and Limitations. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 87, 2926–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, R.; Aluguri, R.; Manna, S.; Ghosh, A.; Satyam, P.V.; Ray, S.K. Multilayer Ge Nanocrystals Embedded within Al2O3 Matrix for High Performance Floating Gate Memory Devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 093102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehninger, D.; Seidel, P.; Geyer, M.; Schneider, F.; Klemm, V.; Rafaja, D.; von Borany, J.; Heitmann, J. Charge Trapping of Ge-Nanocrystals Embedded in TaZrOx Dielectric Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 023116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palade, C.; Lepadatu, A.M.; Slav, A.; Lazanu, S.; Teodorescu, V.S.; Stoica, T.; Ciurea, M.L. Material Parameters from Frequency Dispersion Simulation of Floating Gate Memory with Ge Nanocrystals in HfO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 428, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavarache, I.; Palade, C.; Maraloiu, V.A.; Teodorescu, V.S.; Stoica, T.; Ciurea, M.L. Annealing Effects on the Charging–Discharging Mechanism in Trilayer Al2O3/Ge/Al2O3 Memory Structures. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, T.P.; Liu, Z.; Wong, J.I.; Zhang, W.L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Effect of Annealing on Charge Transfer in Ge Nanocrystal Based Nonvolatile Memory Structure. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.F.; Lu, X.B.; Dai, J.Y.; Chan, H.L.W.; Jelenkovic, E.; Tong, K.Y. Memory Effect and Retention Property of Ge Nanocrystal Embedded Hf-Aluminate High-k Gate Dielectric. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 1202–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Theory of Coulomb-Blockade Oscillations in the Conductance of a Quantum Dot. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Banerjee, S.; Tung, R.T.; Oda, S. Electron Trapping, Storing, and Emission in Nanocrystalline Si Dots by Capacitance–Voltage and Conductance–Voltage Measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.H.; Chim, W.K.; Choi, W.K. Conductance-Voltage Measurements on Germanium Nanocrystal Memory Structures and Effect of Gate Electric Field Coupling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure | Method | Thickness (nm) | Operating Voltage (V) | Memory Window (V) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2/Ge/Al2O3 | Ag-catalyzed Ge CVD | 2/10/20 | −8 to +8 | 7.0 | This work |

| (SiO2/HfO2)/Ge/HfO2 | Ge-HfO2 MS | (2.5/8)/7/22 | −4 to +5 | 1.1 | Ref. [29] |

| (SiO2/Al2O3)/Ge/Al2O3 | Ge MS | (3/4)/15/10 | −1 to +15 | 5.6 | Ref. [30] |

| SiO2/Ge/SiO2 | Ge MBE | 5/1/45 | −10 to +10 | 2.2 | Ref. [5] |

| (SiO2/HfO2)/Ge/HfO2 | Ge EBE | (5/5)/6/20 | −4 to +4 | 0.8 | Ref. [18] |

| SiO2/Ge/TaZrOx | Ge-TaZrOx MS | 5/10/15 | −7 to +7 | 5 | Ref. [28] |

| Al2O3/Ge/Al2O3 | Ge MS | 4/5/15 | −5 to +5 | 4.4 | Ref. [27] |

| SiO2/Ge/SiO2 | Ge-ion implantation | 5/6/31 | −4 to +4 | 2.1 | Ref. [31] |

| HfAlO/Ge/HfAlO | Ge PLD | 2.5/5/15 | −6 to +3 | 3.6 | Ref. [32] |

| SiO2/Ge/SiO2 | Ge CVD | 3/8.5/10 | −5 to +3 | 3.5 | Ref. [20] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, C.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, B.; Li, H.; Wu, F.; Chen, D.; Luo, F.; Zhu, Z. Tailoring Ge Nanocrystals via Ag-Catalyzed Chemical Vapor Deposition to Enhance the Performance of Non-Volatile Memory. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020146

Guo C, Zhou Q, Zheng B, Li H, Wu F, Chen D, Luo F, Zhu Z. Tailoring Ge Nanocrystals via Ag-Catalyzed Chemical Vapor Deposition to Enhance the Performance of Non-Volatile Memory. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020146

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Chucai, Qingwei Zhou, Biyuan Zheng, Hansheng Li, Fan Wu, Dan Chen, Fang Luo, and Zhihong Zhu. 2026. "Tailoring Ge Nanocrystals via Ag-Catalyzed Chemical Vapor Deposition to Enhance the Performance of Non-Volatile Memory" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020146

APA StyleGuo, C., Zhou, Q., Zheng, B., Li, H., Wu, F., Chen, D., Luo, F., & Zhu, Z. (2026). Tailoring Ge Nanocrystals via Ag-Catalyzed Chemical Vapor Deposition to Enhance the Performance of Non-Volatile Memory. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020146