First-Principle Study of AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Methods and Calculation Models

2.2. Experimental Details

3. Results

3.1. Phase Structure

3.2. Elastic Properties

3.3. Electronic Structure

4. Conclusions

- AlCoCrFeNi HEA tends to form a dual-phase structure, with the BCC phase being more stable than the FCC phase, as indicated by the formation energy calculations and supported by experimental XRD results.

- The atomic size difference (δ) of 5.44%, negative mixing enthalpy (ΔHmix) of −14.24 kJ/mol, and valence electron concentration (VEC) of 7.2 suggest a preference for dual-phase formation, primarily BCC, with strong thermodynamic driving forces for phase stability.

- The calculated mechanical properties show Young’s modulus of 250 GPa, a shear modulus of 100 GPa, and a bulk modulus of 169 GPa, indicating high stiffness. The Poisson’s ratio of 0.25 and G/B ratio of 0.59 suggest the material is relatively brittle.

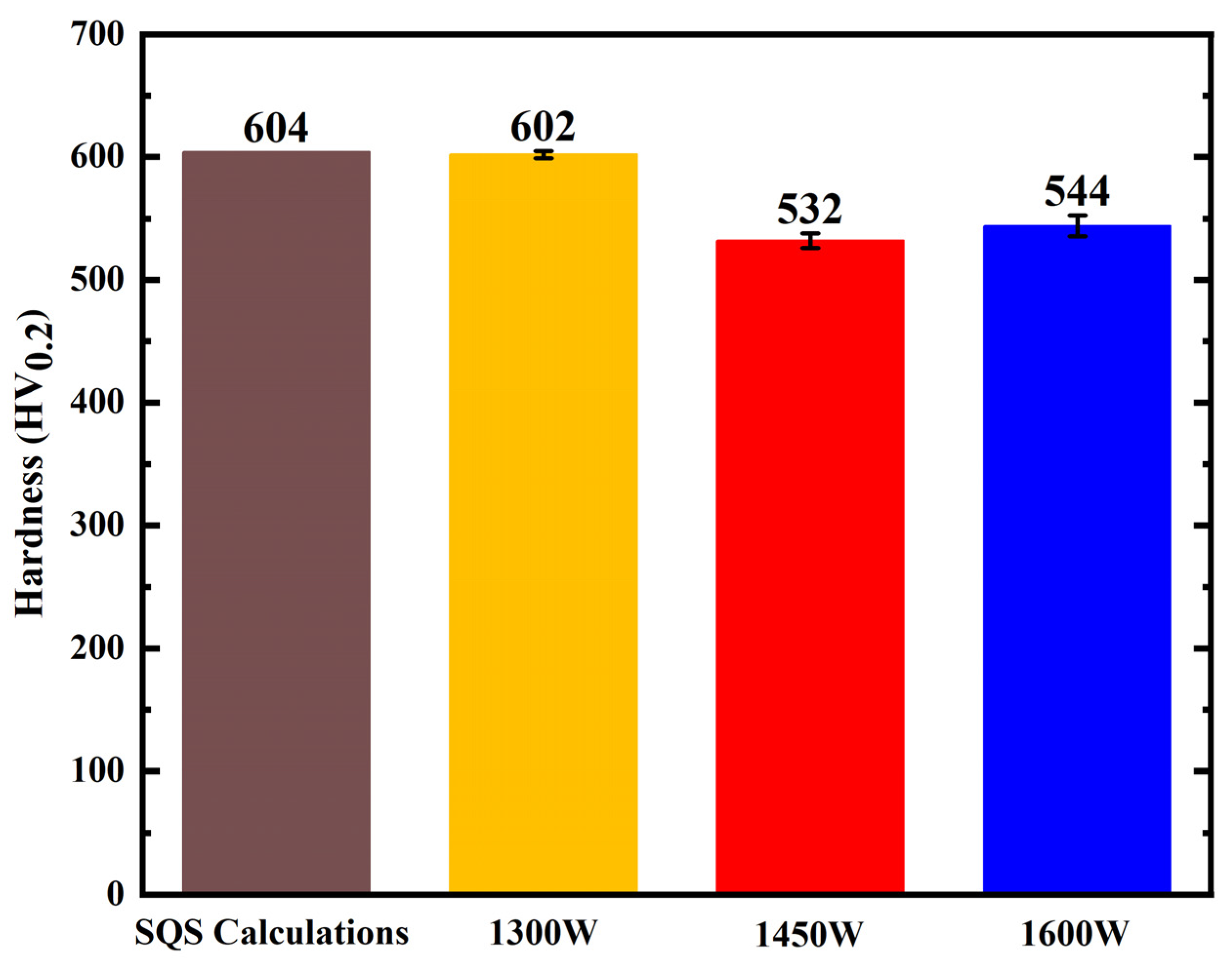

- Experimental microhardness measurements (602 HV0.2 at 1300 W, 532 HV0.2 at 1450 W, and 544 HV0.2 at 1600 W) show good agreement with theoretical predictions, validating the accuracy of the computational approach.

- The electronic structure confirms the metallic nature of AlCoCrFeNi HEAs, with significant contributions from transition metal d-orbitals near the Fermi level, indicating strong metallic bonding and high electrical conductivity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, R.X.; Qiao, J.W.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, Y. Preternatural Hexagonal High-Entropy Alloys, A Review. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2020, 33, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.C.; Zhang, B.; Guo, S.M.; Qiao, J.W.; Hawk, J.A. High-Entropy Alloys in Hexagonal Close-Packed Structure. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 3322–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Research and Application Progress of High-Entropy Alloys. Coatings 2023, 13, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutor, R.K.; Cao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.-Z. Phase Selection, Lattice Distortions, and Mechanical Properties in High-Entropy Alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oketola, A.M.; Adegbola, T.A.; Jamiru, T.; Ogunbiyi, O.; Salifu, S. Advances in High-Entropy Alloy Research, Unraveling Fabrication Techniques, Microstructural Transformations, and Mechanical Properties. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 2025, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartita, R.; Ionita, D.; Demetrescu, I. A Modern Approach to HEAs, From Structure to Properties and Potential Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Bhatt, D.; Satheesh, D.; Kokulnathan, T.; Pant, P.; Bharathi, D.S.; Baskar, L.; Sahoo, N.G.; Palaniappan, A.; Manavalan, K. High entropy alloys, a comprehensive review of synthesis, properties, and characterization for electrochemical energy conversion and storage applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 37663–37699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Jing, H.; Liu, C.; Qiu, C.; Ling, X. High-Entropy Materials for Prospective Biomedical Applications, Challenges and Opportunities. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2406521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Li, S.; Qian, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yuan, H.; Jiang, P.; Guo, R.; Wang, L. High-Entropy Alloys as a Platform for Catalysis, Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11280–11306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.; Radhika, N.; Saleh, B. Effect of Additional Alloying Elements on Microstructure and Properties of AlCoCrFeNi High Entropy Alloy System, A Comprehensive Review. Met. Mater. Int. 2025, 31, 285–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangireddy, S.; Gwalani, B.; Soni, V.; Banerjee, R.; Mishra, R.S. Contrasting mechanical behavior in precipitation hardenable AlXCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy microstructures, Single phase FCC vs. dual phase FCC-BCC. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 739, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemali, E.; Sonkusare, R.; Biswas, K.; Gurao, N.P. In-situ study of crack initiation and propagation in a dual phase AlCoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 710, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Wang, C.; Lei, J.; Yang, T.; Ji, V.; Song, P.; Huang, T.; Zhang, X. Combined effect of B2 phase transformation and FCC/BCC lamellar structure on the mechanical property of heat treated dual-phase Al0.7CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1020, 179456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wu, J.; Yong, L.; Liu, N.; Yang, J. Investigation of mechanical properties and lead-bismuth eutectic corrosion resistance of Al2O3 coatings doped silicon. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 9079–9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Wu, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Liu, H.D.; Ren, F.; Wang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G. Lead-bismuth eutectic (LBE) corrosion mechanism of nano-amorphous composite TiSiN coatings synthesized by cathodic arc ion plating. Corros. Sci. 2021, 183, 109264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, L.; He, F.; Wang, S. Preparation of Cr-N coatings on 316H stainless steel via pack chromizing and gas nitriding, and their resistance to liquid metal corrosion in early stages. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 481, 130665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, Y.; Sato, H.; Yokota, H.; Suzuki, T. Applicability of Al-Powder-Alloy Coating to Corrosion Barriers of 316SS in Liquid Lead-Bismuth Eutectic. Mater. Trans. 2011, 52, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Gan, S.; Wang, R.; Ge, F.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Polcar, T.; et al. Corrosion behavior of Cr coating on ferritic/martensitic steels in liquid lead-bismuth eutectic at 600 °C and 700 °C. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3958–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivai, A.K.; Takahashi, M. Corrosion investigations of Al–Fe-coated steels, high Cr steels, refractory metals and ceramics in lead alloys at 700 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2010, 398, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Deng, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, L.; Mao, J.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J. Synergistic effect of simultaneous proton irradiation and LBE corrosion on the microstructure of the FeCrAl(Y) coatings. Corros. Sci. 2024, 229, 111874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, P.; Liaw, P.K. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloy films and coatings, a review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2018, 6, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Li, Y. Recent advances in the performance and mechanisms of high-entropy alloys under low-and high-temperature conditions. Coatings 2025, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Tong, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, X.; Han, Y.; Hua, K.; Wang, H. Wear-Resistance of High-Entropy Alloy Coatings and High-Entropy Alloy-Based Composite Coatings Prepared by the Laser Cladding Technology, A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2300426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei, M.H.; Zohrevand, M.; Zhang, N. Applications of machine learning in high-entropy alloys, a review of recent advances in design, discovery, and characterization. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 20548–20605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, U.L.; Raghavendra, H. Review on the transition from conventional to multi-component-based nano-high-entropy alloys—NHEAs. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 139, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Fang, H.; Chen, K.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Lu, Z.; Wen, Z. Engineering High-Density Grain Boundaries in Ru0.8Ir0.2Ox Solid-Solution Nanosheets for Efficient and Durable OER Electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2501607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, P.; Nath Ghosh, N. A review on the use of DFT for the prediction of the properties of nanomaterials. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27897–27924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, E.; Zwane, R.; Fox, R.; Reilly, A.M.; Guerin, S. Density functional theory predictions of the mechanical properties of crystalline materials. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 5697–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Shin, Y.; Persson, K.A. Computational predictions of energy materials using density functional theory. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; He, F.; Tasan, C.C. Metastability in high-entropy alloys, A review. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 2924–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, B.; Mendez-Martin, F.; Völker, B.; George, E.P.; Clemens, H.; Pippan, R.; Hohenwarter, A. Mechanical properties, microstructure and thermal stability of a nanocrystalline CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2015, 96, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wu, Y.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; An, K.; Wu, W.; Lu, Z. Phase-transformation ductilization of brittle high-entropy alloys via metastability engineering. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.C.; Lee, H.; Sharma, A.; Ahn, B. Controlled Valence Electron Concentration Approach to Tailor the Microstructure and Phase Stability of an Entropy-Enhanced AlCoCrFeNi Alloy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2022, 53, 1831–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Sahara, R.; Tsuchiya, K. First-principles study of the phase stability and elastic properties of Ti-X alloys (X = Mo, Nb, Al, Sn, Zr, Fe, Co, and O). J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 727, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, S.; Guo, Q.; Hou, H. Computation of stability, elasticity and thermodynamics in equiatomic AlCrFeNi medium-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 2566–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Lin, J.P.; Chen, G.L.; Liaw, P.K. Solid-Solution Phase Formation Rules for Multi-component Alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Inoue, A. Classification of Bulk Metallic Glasses by Atomic Size Difference, Mixing Enthalpy and Period of Constituent Elements and Its Ap-plication to Characterization of the Main Alloying Element. Mater. Trans. JIM 2000, 41, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of high-entropy stabilized solid-solution in multi-component alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Varga, L.K.; Chen, N.; Shen, J.; Vitos, L. Empirical design of single phase high-entropy alloys with high hardness. Intermetallics 2015, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liu, C.T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys, Formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2011, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Hu, Y.; Liang, X.; Tong, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Titanium alloying enhancement of mechanical properties of NbTaMoW refractory high-Entropy alloy, First-principles and experiments perspective. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 857, 157542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Curtin, W.A. First principles study of the effect of hydrogen in austenitic stainless steels and high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2020, 200, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, T. An ab initio and experimental studies of the structure, mechanical parameters and state density on the refractory high-entropy alloy systems. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 714, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Ruan, Z.; Fan, T.; Chen, D.; Wu, Y.; Tang, P. First-principles calculations to investigate stability, mechanical and thermo-dynamic properties of AlxTMy intermetallics in aluminum alloys. Solid State Commun. 2023, 376, 115361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Xie, H.; Fan, T.; Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Cao, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Bai, P. Effects of Al and La elements on mechanical properties of CoNiFe0.6Cr0.6 high-entropy alloys, a first-principles study. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, N.; Sistla, Y.S.; Burela, R.G.; Gupta, A. Structural, Electronic, Mechanical and Thermal Properties of AlxCoCrFeNi (0 ≤ x ≤ 2) High Entropy Alloy Using Density Functional Theory. Met. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 3349–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.Y.; Marzari, N. Improving the Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Nanotube Networks, A First-Principles Study. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9726–9736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Ai, X.; Shen, Y.; Zou, X. d–sp orbital hybridization, a strategy for activity improvement of transition metal catalysts. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7730–7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Type | δ (%) | ΔHmix (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| AlCoCrFeNi HEA | 5.44 | −14.24 |

| HEA | Elastic Constants Cij (GPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | C12 | C44 | |

| AlCoCrFeNi | 232.3 | 137.4 | 135.3 |

| HEA | E | G | B | ν | G/B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlCoCrFeNi | 250.0 | 100.0 | 169.0 | 0.25 | 0.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, A.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, S. First-Principle Study of AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010020

Huang A, Liu Y, Huang J, Liu J, Yang S. First-Principle Study of AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Andi, Yilong Liu, Jinghao Huang, Jingang Liu, and Shiping Yang. 2026. "First-Principle Study of AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010020

APA StyleHuang, A., Liu, Y., Huang, J., Liu, J., & Yang, S. (2026). First-Principle Study of AlCoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010020