Multiferroic Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3-CoFe2O4 Janus-Type Nanofibers and Their Nanoscale Magnetoelectric Coupling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Synthesis of PZT-CFO Single-Phase and Janus Nanofibers

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystalline Structure

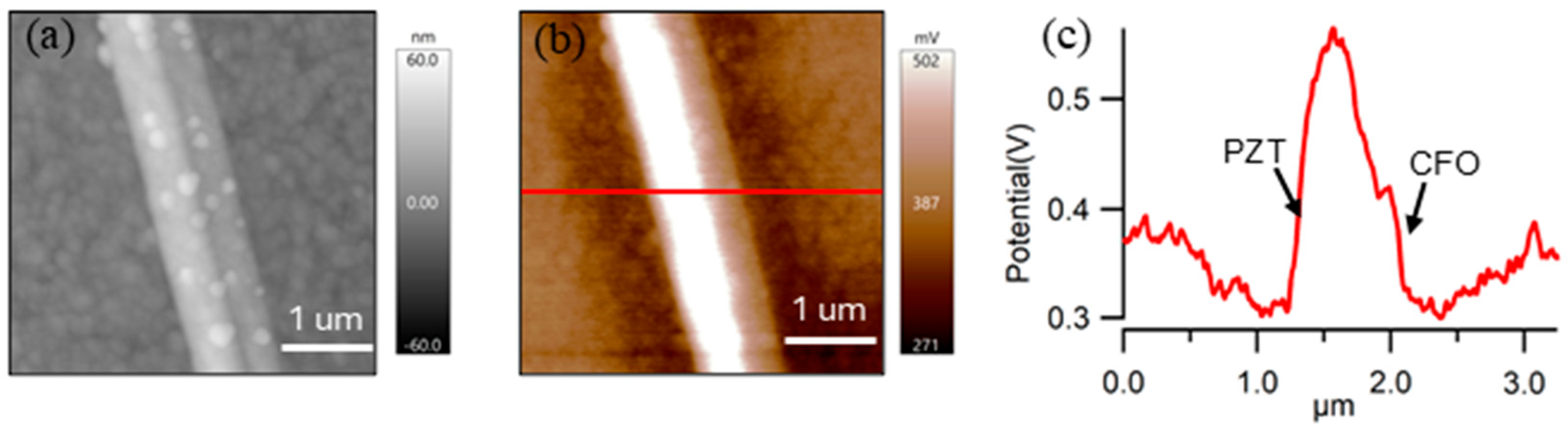

3.2. Morphology and Surface Potential

3.3. Ferromagnetic Property

3.4. Ferroelectric and ME Coupling Properties

4. Conclusions

- •

- Structural and morphological analysis through X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and atomic force microscopy (AFM) confirmed the biphasic composition, high phase purity, and the distinctive side-by-side architecture of the nanofibers.

- •

- Nanoscale functional mapping using Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) revealed a pronounced surface potential contrast between the two halves of an individual fiber, providing direct evidence for the Janus heterostructure with phase-specific electronic properties.

- •

- Macroscopic magnetic measurement by vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) demonstrated clear room-temperature ferromagnetism, with magnetic parameters influenced by both dilution and interfacial effects within the composite.

- •

- Local electromechanical and magnetoelectric characterization was achieved via dual-frequency resonance tracking piezoresponse force microscopy (DFRT-PFM). This critical analysis quantified the intrinsic piezoelectric response and, under an applied magnetic field, captured a definitive enhancement from 15 pm to 19 pm.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eerenstein, W.; Mathur, N.D.; Scott, J.F. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 2006, 442, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, C.W.; Bichurin, M.I.; Dong, S.; Viehland, D.; Srinivasan, G. Multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: Historical perspective, status, and future directions. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 031101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y.; Nan, C.W. Multiferroic magnetoelectric composite nanostructures. NPG Asia Mater. 2010, 2, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawes, G.; Srinivasan, G. Introduction to magnetoelectric coupling and multiferroic film. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 243001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kotnala, R.K. A review on current status and mechanisms of room-temperature magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroics for device applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 12710–12737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Kumar, A.; Scott, J.F.; Katiyar, R.S. Multifunctional magnetoelectric materials for device applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 504002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.K.; Kumari, S.; Rack, P.D. Magnetoelectric composites: Applications, coupling mechanisms, and future directions. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Shankar, S.; Kumar, A.; Anshul, A.; Jayasimhadri, M.; Thakur, O.P. Progress in multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials: Applications, opportunities and challenges. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 19487–19510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Majumder, S.B. Recent advances in multiferroic thin films and composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 538, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.S.; Starr, J.D.; Budi, M.A.K. Prospects for nanostructured multiferroic composite materials. Scr. Mater. 2014, 74, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.W.; Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: A magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Nan, C. Evidence for stress-mediated magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroic bilayer films from magnetic-field-dependent Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2009, 79, 180406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhai, J.; Li, J.F.; Viehland, D.; Summers, E. Strong magnetoelectric charge coupling in stress-biased multilayer-piezoelectric/magnetostrictive composites. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 124102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, S.; Li, J.Y. The effective magnetoelectric coefficients of polycrystalline multiferroic composites. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 4135–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Nan, C.W. Recent progress in multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: From bulk to thin films. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palneedi, H.; Annapureddy, V.; Priya, S.; Ryu, J. Status and perspectives of multiferroic magnetoelectric composite materials and applications. Actuators 2016, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.W.; Cai, N.; Shi, Z.; Zhai, J.; Liu, G.; Lin, Y. Large magnetoelectric response in multiferroic polymer-based composites. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2005, 71, 014102. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, D.K.; Puli, V.S.; Kumari, S.; Sahoo, S.; Das, P.T.; Pradhan, K.; Pradhan, D.K.; Scott, J.F.; Katiyar, R.S. Studies of phase transitions and magnetoelectric coupling in PFN-CZFO multiferroic composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 1936–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed-Ul-Haq, M.; Shvartsman, V.V.; Salamon, S.; Wende, H.; Trivedi, H.; Mumtaz, A.; Lupascu, D.C. A new (Ba, Ca)(Ti, Zr) O3 based multiferroic composite with large magnetoelectric effect. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32164. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.M.; Chen, L.Q.; Nan, C.W. Multiferroic heterostructures integrating ferroelectric and magnetic materials. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Matyushov, A.; Hayes, P.; Schell, V.; Dong, C.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Will-Cole, A.; Quandt, E.; Martins, P.; et al. Roadmap on magnetoelectric materials and devices. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 400157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matavž, A.; Koželj, P.; Winkler, M.; Geirhos, K.; Lunkenheimer, P.; Bobnar, V. Nanostructured multiferroic Pb(Zr, Ti)O3–NiFe2O4 thin-film composites. Thin Solid Film. 2021, 732, 138740. [Google Scholar]

- Gareeva, Z.; Shulga, N.; Doroshenko, R.; Zvezdin, A. Electric field control of magnetic states in ferromagnetic–multiferroic nanostructures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 22380–22387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, P.; Narayana, Y.; Kalarikkal, N. An effective strategy for the development of multiferroic composite nanostructures with enhanced magnetoelectric coupling performance: A perovskite–spinel approach. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 4866–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Chen, W.Q.; Xie, S.H.; Yang, J.S.; Li, J.Y. The magnetoelectric effects in multiferroic composite nanofibers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Ma, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Multiferroic CoFe2O4–Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 core-shell nanofibers and their magnetoelectric coupling. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 3152–3158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Miao, H.; Xie, S. Multiferroic CoFe2O4–BiFeO3 core–shell nanofibers and their nanoscale magnetoelectric coupling. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 29, 657–664. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, J.D.; Andrew, J.S. Janus-type bi-phasic functional nanofibers. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4151–4153. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.H.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lan, L.N.; Jin, G.; Zhou, Y.C. Electrospinning and multiferroic properties of NiFe2O4–Pb (Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 composite nanofibers. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 024115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ou, Y.; Ma, F.; Yang, Q.; Tan, X.; Xie, S. Synthesis of multiferroic Pb (Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3–CoFe2O4 core–shell nanofibers by coaxial electrospinning. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2013, 5, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, J.D.; Budi, M.A.K.; Andrew, J.S. Processing-property relationships in electrospun Janus-type biphasic ceramic nanofibers. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 98, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Shen, Y.; Wang, C.A.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Cheng, J.; Ye, Y.; Shen, R. Fabrication of energetic aluminum core/hydrophobic shell nanofibers via coaxial electrospinning. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 132001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abduljabbar, A.; Farooq, I. Electrospun polymer nanofibers: Processing, properties, and applications. Polymers 2022, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Shen, W.; Wu, S.; Ge, X.; Ao, F.; Ning, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Z. Electrospun polymers: Using devices to enhance their potential for biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 186, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Lin, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Huang, S.; Yao, L.; Cheng, J.; et al. One-dimensional electrospun ceramic nanomaterials and their sensing applications. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 765–785. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wu, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y. Research progress on electrospun high-strength micro/nano ceramic fibers. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 34169–34183. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.T.; Si, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Direct synthesis of highly stretchable ceramic nanofibrous aerogels via 3D reaction electrospinning. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arash, S.; Kharal, G.; Chavez, B.L.; Ferson, N.D.; Mills, S.C.; Andrew, J.S.; Crawford, T.M.; Wu, Y. Multiferroicity and semi-cylindrical alignment in Janus nanofiber aggregates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Pan, K.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Nanomechanics of multiferroic composite nanofibers via local excitation piezoresponse force microscopy. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 126, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qajjour, M.; Maaouni, N.; Mhirech, A.; Kabouchi, B.; Bahmad, L.; Benomar, W.O. Dilution effect on the magnetic properties of the spin Lieb nanolattice: Monte Carlo simulations. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 482, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Hu, S.Y.; Choudhury, S.; Baskes, M.I.; Saxena, A.; Lookman, T.; Jia, Q.X.; Schlom, D.G.; Chen, L.Q. Influence of interfacial dislocations on hysteresis loops of ferroelectric films. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, Q.; Wang, T.; Zhao, J.; Mei, H.; Gong, W. Multiferroic Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3-CoFe2O4 Janus-Type Nanofibers and Their Nanoscale Magnetoelectric Coupling. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010002

Zhu Q, Wang T, Zhao J, Mei H, Gong W. Multiferroic Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3-CoFe2O4 Janus-Type Nanofibers and Their Nanoscale Magnetoelectric Coupling. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Qingfeng, Ting Wang, Junfeng Zhao, Haijuan Mei, and Weiping Gong. 2026. "Multiferroic Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3-CoFe2O4 Janus-Type Nanofibers and Their Nanoscale Magnetoelectric Coupling" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010002

APA StyleZhu, Q., Wang, T., Zhao, J., Mei, H., & Gong, W. (2026). Multiferroic Pb(Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3-CoFe2O4 Janus-Type Nanofibers and Their Nanoscale Magnetoelectric Coupling. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010002