Defect-Mediated Threshold Voltage Tuning in β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs via Fluorine Plasma Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

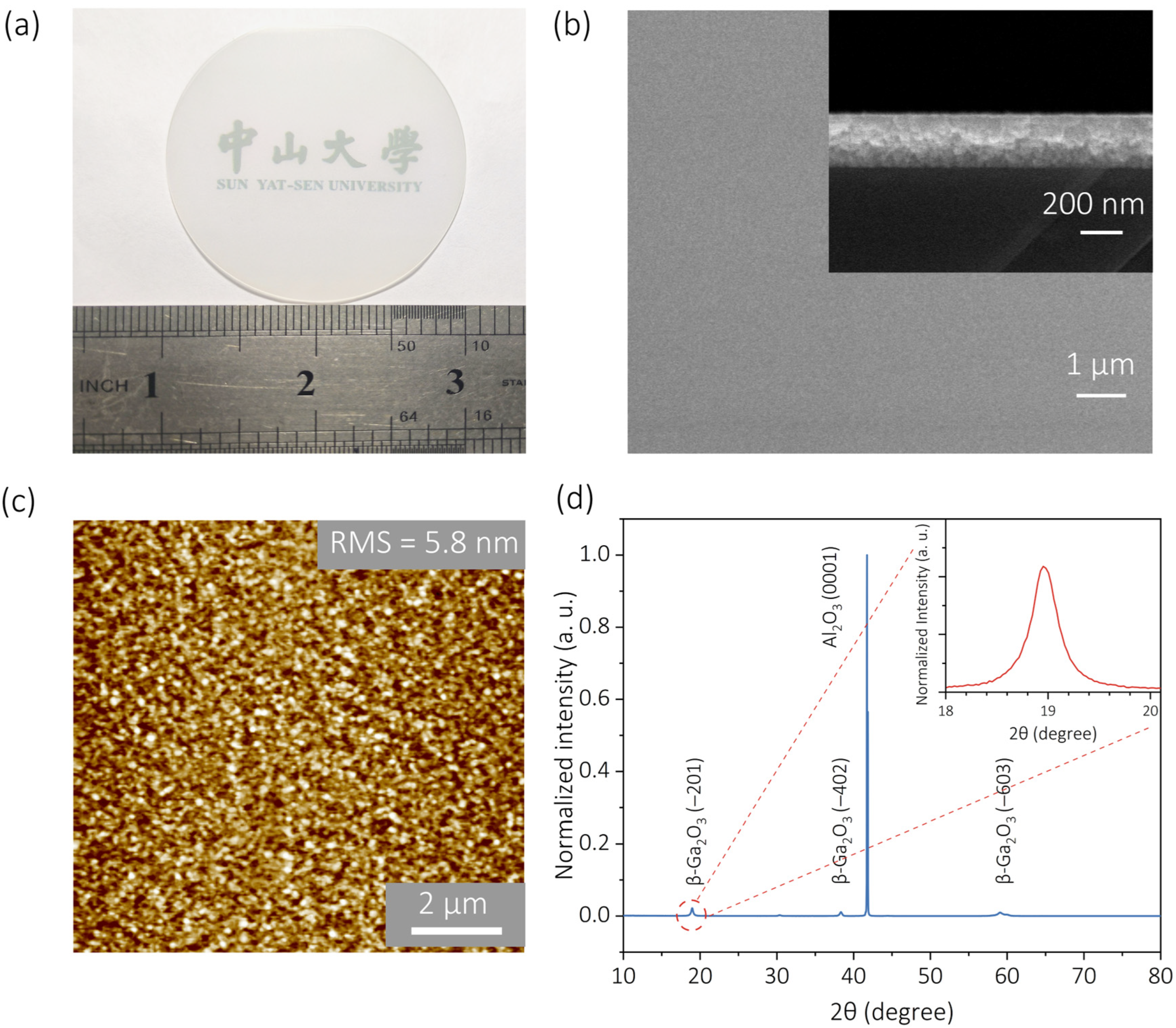

2.1. Growth of β-Ga2O3 Thin Films

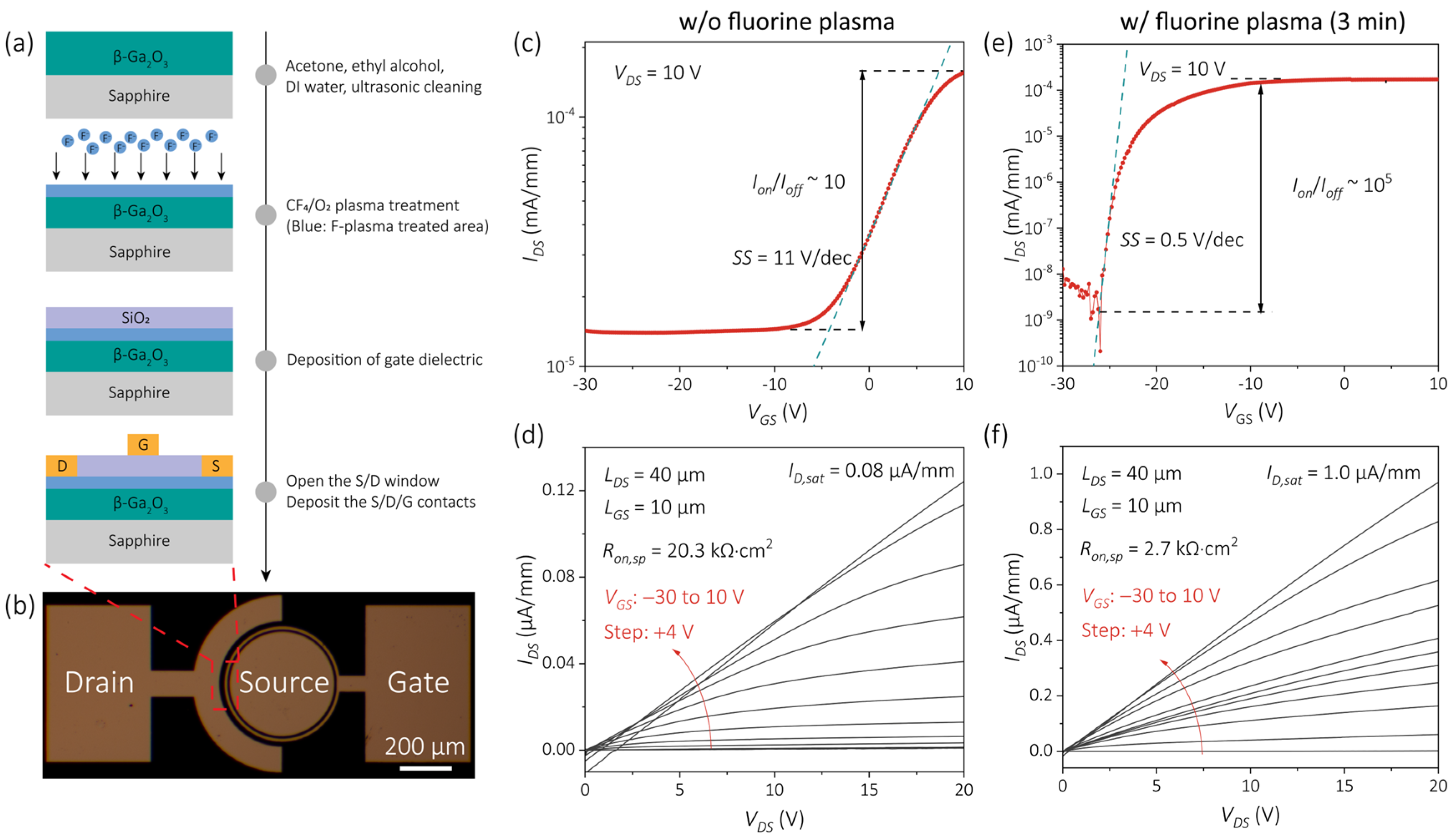

2.2. Device Fabrication

2.3. Characterization

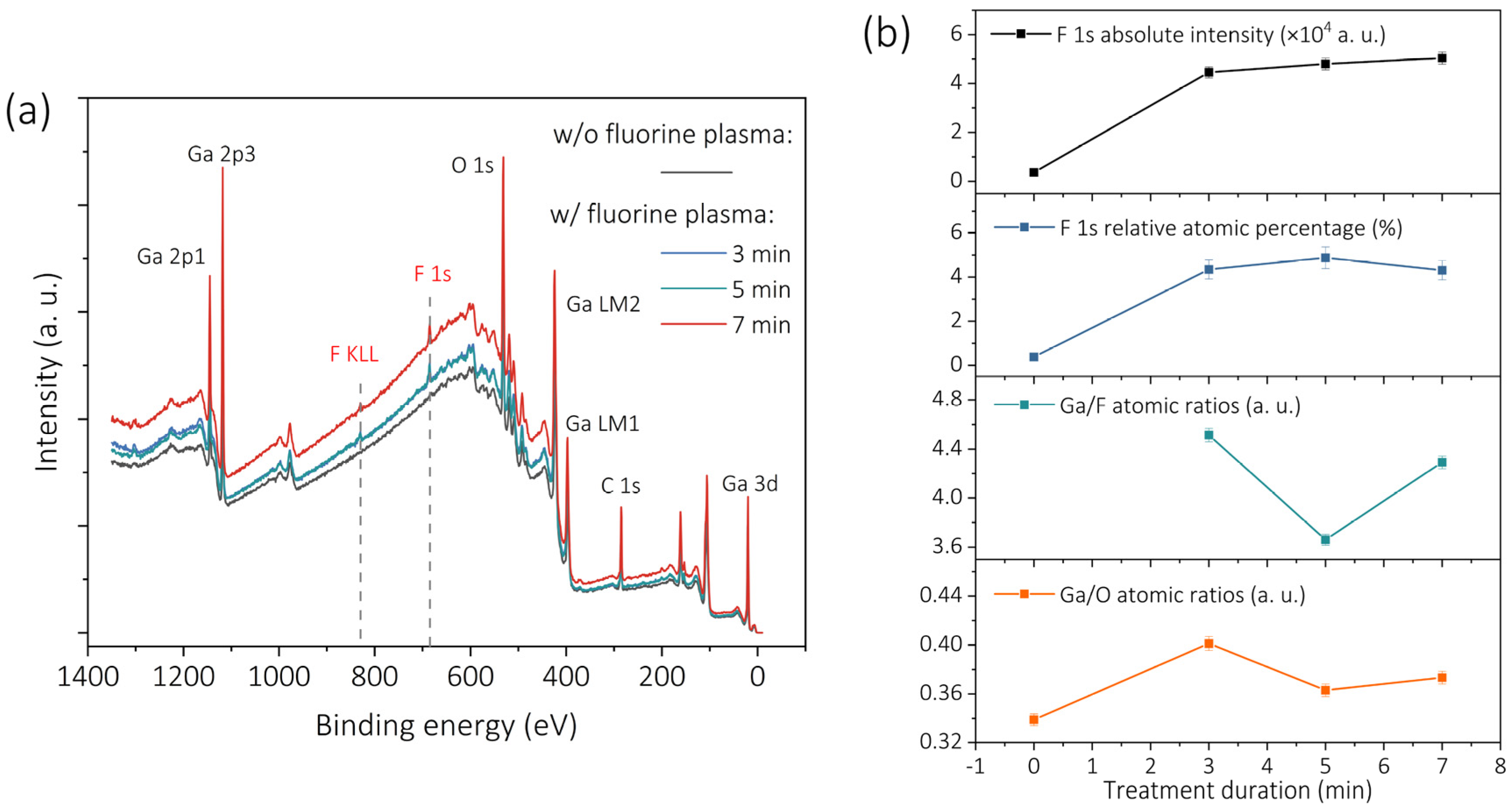

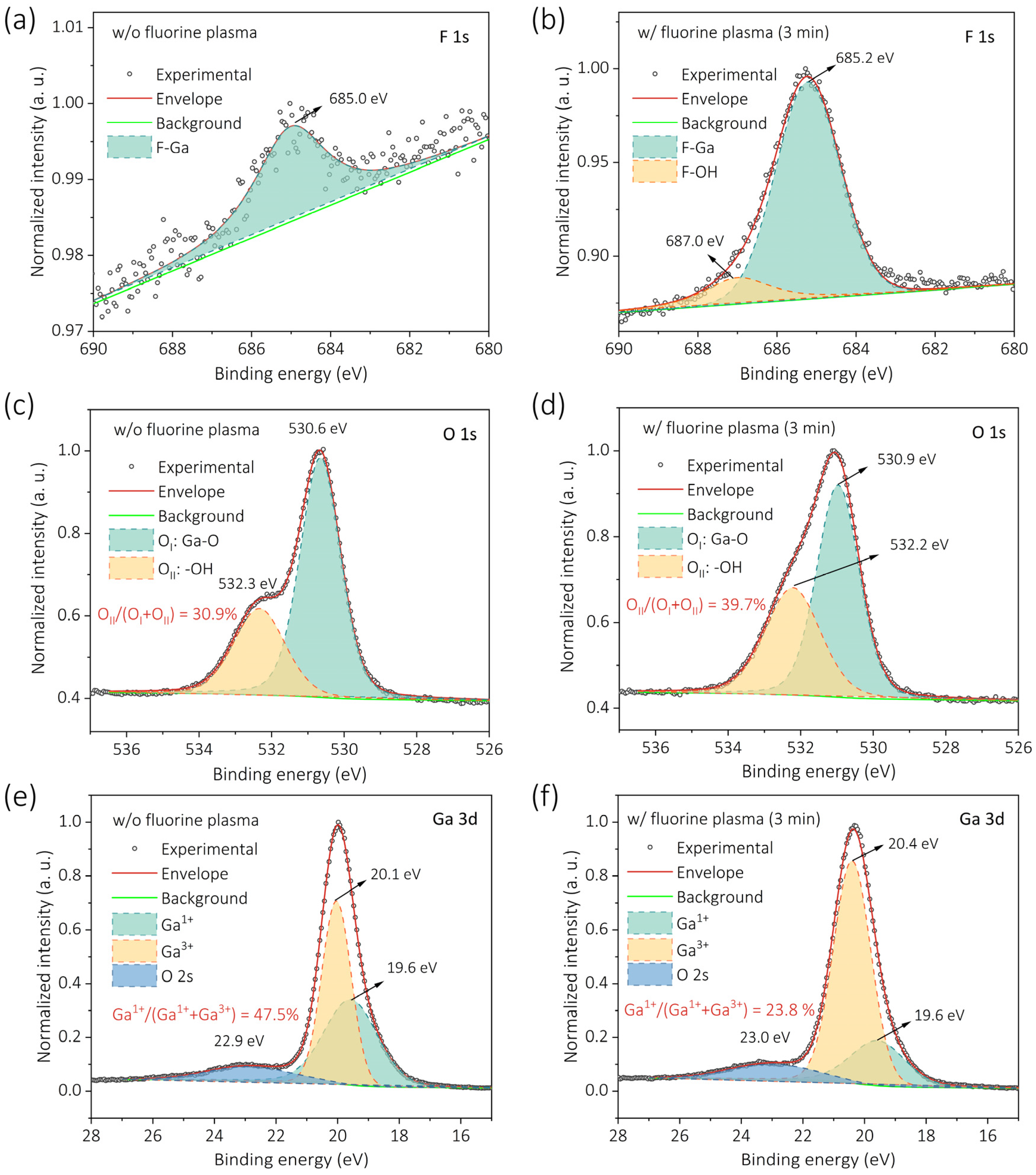

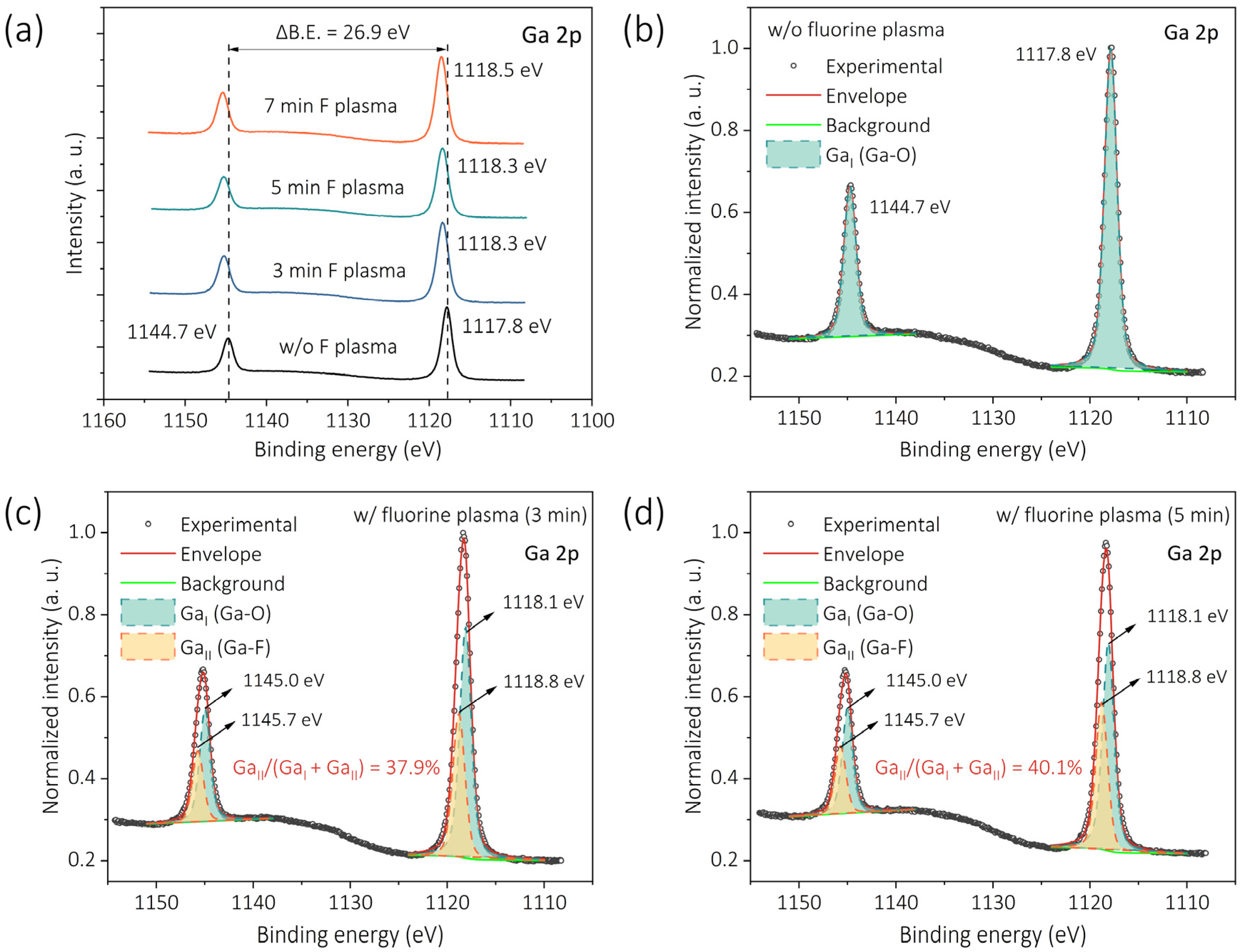

2.4. XPS Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, K.-H.; Karpov, I.; Olsson, R.H.; Jariwala, D. Wurtzite and fluorite ferroelectric materials for electronic memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.M.; Riel, H. Tunnel field-effect transistors as energy-efficient electronic switches. Nature 2011, 479, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, P. The road for 2D semiconductors in the silicon age. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliga, B.J. Power semiconductor device figure of merit for high-frequency applications. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1989, 10, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trew, R.J. SiC and GaN transistors—Is there one winner for microwave power applications? Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1032–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.J.; Yang, J.; Cary, P.H., IV; Ren, F.; Kim, J.; Tadjer, M.J.; Mastro, M.A. A review of Ga2O3 materials, processing, and devices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 011301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashiwaki, M.; Jessen, G.H. Guest editorial: The dawn of gallium oxide microelectronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 060401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, M.A.; Kuramata, A.; Calkins, J.; Kim, J.; Ren, F.; Pearton, S.J. Perspective—Opportunities and future directions for Ga2O3. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2017, 6, P356–P359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Ma, P.; Hao, Y. A review of the most recent progresses of state-of-art gallium oxide power devices. J. Semicond. 2019, 40, 011803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tang, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, T.; Dai, S.; Bian, C.; Li, B.; et al. 702.3 A·cm−2/10.4 mΩ·cm2 β-Ga2O3 U-shape trench gate MOSFET with N-ion implantation. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2023, 44, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Zeng, K.; Saha, S.; Singisetti, U. Field-plated lateral Ga2O3 MOSFETs with polymer passivation and 8.03 kV breakdown voltage. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2020, 41, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, H.; Lei, W.; Cai, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, H.; Ye, J.; et al. Demonstration of the p-NiOx/n-Ga2O3 heterojunction gate FETs and diodes with BV2/Ron,sp figures of merit of 0.39 GW/cm2 and 1.38 GW/cm2. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2021, 42, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Higashiwaki, M.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diodes fabricated by using single-crystal β-Ga2O3 (010) substrates. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2013, 34, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Gangireddy, R.; Kim, J.; Das, K.K.; Davis, R.F.; Porter, L.M. Electrical behavior of β-Ga2O3 Schottky diodes with different Schottky metals. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2017, 35, 03D113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sparks, Z.; Ren, F.; Pearton, S.J.; Tadjer, M. Effect of surface treatments on electrical properties of β-Ga2O3. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2018, 36, 061201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tadjer, M.J.; Mastro, M.A.; Kim, J. Controlling the threshold voltage of β-Ga2O3 field-effect transistors via remote fluorine plasma treatment. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 8855–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lau, K.M.; Chen, K.J. Control of threshold voltage of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs by fluoride-based plasma treatment: From depletion mode to enhancement mode. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2006, 53, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.X.; Lai, P.T. Fluorinated InGaZnO thin-film transistor with HfLaO gate dielectric. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2014, 35, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Z.; Pei, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zhou, H.; Lu, X.; Lau, K.M.; Wang, G. Leakage current reduction in β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diodes by CF4 plasma treatment. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2020, 41, 1312–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hao, L.; Zhao, K.; Gong, C.; Deng, G.; Dai, K.; Wei, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X. Variable fluoride ion implantation compound termination in β-Ga2O3 Schottky barrier diode with stress test. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 5941–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Feng, J.; Huang, S.; Yang, N.; Qiu, B.; Duan, E.; Liu, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Q. Impact of fluorine plasma and electrothermal annealing on the interfacial properties at Ni/β-Ga2O3 Schottky contacts. J. Semicond. 2026, 47, 022102-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, J.B.; Weber, J.R.; Janotti, A.; Van De Walle, C.G. Oxygen vacancies and donor impurities in β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 142106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, S.; Nishinaka, H.; Yoshimoto, M. Growth and characterization of F-doped α-Ga2O3 thin films with low electrical resistivity. Thin Solid Film. 2019, 682, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Zhu, S.; Luo, T.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; Pei, Y.; Wang, G.; Lu, X. Heteroepitaxial ε-Ga2O3 MOSFETs on a 4-inch sapphire substrate with a power figure of merit of 0.29 GW/cm2. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and ICs (ISPSD), Bremen, Germany, 2–6 June 2024; pp. 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.J.; Yang, J.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Park, R.; Lee, G.; Chung, R.B.K.; Yoo, G. Fluorine-based plasma treatment for hetero-epitaxial β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 558, 149936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Li, X.; Han, G.; Huang, L.; Li, F.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Y. (AlGa)2O3 solar-blind photodetectors on sapphire with wider bandgap and improved responsivity. Opt. Mater. Express 2017, 7, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, P.; Bierwagen, O. Reaction kinetics and growth window for plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy of Ga2O3: Incorporation of Ga vs. Ga2O desorption. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 072101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, S.; Han, L.; Neal, A.T.; Mou, S.; Tadjer, M.J.; French, R.H.; Zhao, H. Heteroepitaxy of N-type β-Ga2O3 thin films on sapphire substrate by low pressure chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 132103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, L.F.; Brown, J.M.; Ramer, J.C.; Zhang, L.; Hersee, S.D.; Zolper, J.C. Nonalloyed Ti/Al ohmic contacts to n-type GaN using high-temperature premetallization anneal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 2737–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, G.S.; Das, M.B. The effects of contact size and non-zero metal resistance on the determination of specific contact resistance. Solid-State Electron. 1982, 25, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, H.; Feng, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Experimental Investigation on Threshold Voltage Instability for β -Ga2O3 MOSFET Under Electrical and Thermal Stress. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 5048–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukarev, A.; Korolkov, D. XPS study of group IA carbonates. Open Chem. 2004, 2, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Ortiz, S.A.; Botero, M.A.; Ospina, R. XPS characterization of ciprofloxacin tablet. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2022, 29, 014020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.K.; Fiedler, S.; Irvine, C.P.; Matar, F.; Phillips, M.R.; Ton-That, C. Defect passivation and enhanced UV emission in β-Ga2O3 via remote fluorine plasma treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 687, 162250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gu, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Ni, C. First-principles study of fluorine-doped zinc oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 122101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Lee, J.G.; Joo, Y.-H.; Hou, B.; Um, D.-S.; Kim, C.-I. Etching characteristics and surface properties of fluorine-doped tin oxide thin films under CF4-based plasma treatment. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polydorou, E.; Zeniou, A.; Tsikritzis, D.; Soultati, A.; Sakellis, I.; Gardelis, S.; Papadopoulos, T.A.; Briscoe, J.; Palilis, L.C.; Kennou, S.; et al. Surface passivation effect by fluorine plasma treatment on ZnO for efficiency and lifetime improvement of inverted polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 11844–11858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaño, M.C.S.; Asubar, J.T.; Yatabe, Z.; David, M.Y.; Uenuma, M.; Tokuda, H.; Uraoka, Y.; Kuzuhara, M.; Tani, M. On the presence of Ga2O sub-oxide in high-pressure water vapor annealed AlGaN surface by combined XPS and first-principles methods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 481, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, T.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, R.; Yang, W.; He, J.; Chen, X.; Dai, N. Low Deposition Temperature Amorphous ALD-Ga2O3 Thin Films and Decoration with MoS2 Multilayers toward Flexible Solar-Blind Photodetectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 41802–41809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo Scientific XPS: Knowledge Base (Web-Version). Available online: http://xpssimplified.com/knowledgebase.php (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Crist, B.V. Handbooks of Monochromatic XPS Spectra (Web-Version, Vol. 2); XPS International LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2005; p. 956. Available online: www.xpsdata.com (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Zatsepin, D.A.; Boukhvalov, D.W.; Zatsepin, A.F.; Kuznetsova, Y.A.; Gogova, D.; Shur, V.Y.; Esin, A.A. Atomic structure, electronic states, and optical properties of epitaxially grown β-Ga2O3 layers. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018, 120, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 3rd ed.; John Wiley, Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Higashiwaki, M.; Sasaki, K.; Kamimura, T.; Wong, M.H.; Krishnamurthy, D.; Kuramata, A.; Masui, T.; Yamakoshi, S. Depletion-mode Ga2O3 metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors on β-Ga2O3 (010) substrates and temperature dependence of their device characteristics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 123511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Cai, Y.; Yan, G.; Hu, Z.; Dang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Cheng, H.; Lian, X.; Xu, Y.; et al. A 800 V β-Ga2O3 metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor with high-power figure of merit of over 86.3 MW cm−2. Phys. Status Solidi A—Appl. Mat. 2019, 216, 1900421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; McClintock, R.; Jaud, A.; Dehzangi, A.; Razeghi, M. MOCVD grown β-Ga2O3 metal-oxide-semiconductor field effect transistors on sapphire. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 095503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Tarntair, F.-G.; Kao, Y.-C.; Tumilty, N.; Shieh, J.-M.; Hsu, S.-H.; Hsiao, C.-L.; Horng, R.-H. β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs electrical characteristic study of various etching depths grown on sapphire substrate by MOCVD. Discov. Nano. 2023, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Tarntair, F.-G.; Kao, Y.-C.; Tumilty, N.; Horng, R.-H. Undoped β-Ga2O3 layer thickness effect on the performance of MOSFETs grown on a sapphire substrate. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.; Hsu, F.-Y.; Ko, R.-M.; Hsu, W.-C. Heteroepitaxial growth of Sn δ-doped β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs on c-plane sapphire via nonvacuum mist-CVD process. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

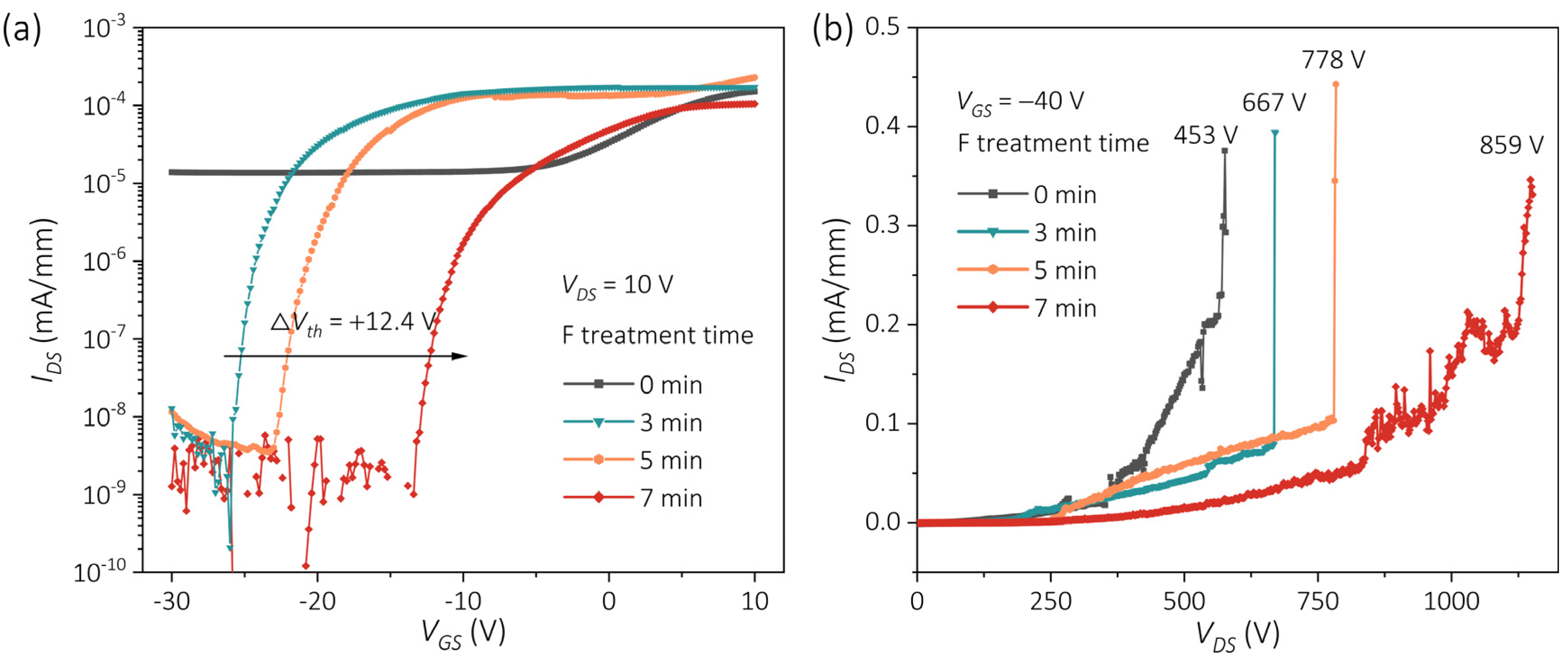

| Performance | F0 | F3 | F5 | F7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 105 | 105 | 105 | |

| (V/dec) | 11 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.63 |

| (V) | - | −25.8 | −22.8 | −13.4 |

| (V) | 453 | 667 | 778 | 859 |

| (V) | (μm) | (V) | (mΩ·cm2) | (mA/mm) | (mA/mm) | / | (mV/dec) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 370 | - | −15 | - | 39 | 10−9 | 1010 | - | [44] * |

| 2700 | 40 | −12 | 78 kΩ·mm | 0.2 | 10−5 | 105 | - | [11] * |

| 800 | 11.4 | −18 | 7.41 | 238.1 | 10−9 | 108 | 86 | [45] |

| 400 | 40 | −32 | - | 100 | 10−9 | 1011 | 210 | [46] |

| - | 70 | −18 | 117.9 kΩ | 10−1 | 10−7 | 106 | - | [25] |

| 650 | 15 | −8 | - | 10−1 | 10−8 | 107 | - | [47] |

| 770 | 15 | 1.5 | - | 10−4 | 10−8 | 104 | - | |

| 910 | 20 | 1.5 | 223 | 10−3 | 10−7 | 104 | - | [48] |

| 240 | 20 | 1.5 | 752 | 0.7 | 10−5 | 105 | - | |

| 1085 | 15 | −7.5 | 600 | 3.71 | 10−7 | 107 | 313 | [49] |

| 1250 | 15 | −3.9 | 5820 | 0.5 | 10−8 | 107 | 351 | |

| 859 | 40 | −13.4 | 106 | 10−4 | 10−9 | 105 | 630 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, S.; Zhu, H. Defect-Mediated Threshold Voltage Tuning in β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs via Fluorine Plasma Treatment. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241896

Wang L, Zhang Y, Dong J, Wang J, Wang Z, Feng Y, Wang X, Shen S, Zhu H. Defect-Mediated Threshold Voltage Tuning in β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs via Fluorine Plasma Treatment. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241896

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lisheng, Yifan Zhang, Junxing Dong, Jingzhuo Wang, Zenan Wang, Yuan Feng, Xianghu Wang, Si Shen, and Hai Zhu. 2025. "Defect-Mediated Threshold Voltage Tuning in β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs via Fluorine Plasma Treatment" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241896

APA StyleWang, L., Zhang, Y., Dong, J., Wang, J., Wang, Z., Feng, Y., Wang, X., Shen, S., & Zhu, H. (2025). Defect-Mediated Threshold Voltage Tuning in β-Ga2O3 MOSFETs via Fluorine Plasma Treatment. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241896