Large Piezoelectric Response and High Carrier Mobilities Enhanced via 6s2 Hybridization in Bismuth Chalcohalide Monolayers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Methods

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, J.; Song, P.; Di, J.; Li, H. Bismuth-rich bismuth oxyhalides: A new opportunity to trigger high-efficiency photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 21434–21454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurushima, K.; Nakajima, H.; Ogata, T.; Sakai, Y.; Azuma, M.; Mori, S. Relationship between Pb ion off-centering and lone pair electrons. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoop, L.M.; Müchler, L.; Felser, C.; Cava, R.J. Lone Pair Effect, Structural Distortions, and Potential for Superconductivity in Tl Perovskites. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 5479–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabini, D.H.; Laurita, G.; Bechtel, J.S.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Evans, H.A.; Kontos, A.G.; Raptis, Y.S.; Falaras, P.; Van der Ven, A.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; et al. Dynamic Stereochemical Activity of the Sn2+ Lone Pair in Perovskite CsSnBr3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11820–11832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.L.; Malliakas, C.D.; Peters, J.A.; Liu, Z.; Im, J.; Zhao, L.-D.; Sebastian, M.; Jin, H.; Li, H.; Johnsen, S.; et al. Photoconductivity in Tl6SI4: A Novel Semiconductor for Hard Radiation Detection. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, N.J.; Noh, J.H.; Yang, W.S.; Kim, Y.C.; Ryu, S.; Seo, J.; Seok, S.I. Compositional engineering of perovskite materials for high-performance solar cells. Nature 2015, 517, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, M.; Du, J.; Huang, Y. Stabilities, and electronic and piezoelectric properties of two-dimensional tin dichalcogenide derived Janus monolayers. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 13203–13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Ho-Baillie, A.; Snaith, H.J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Zuo, X.; Kang, L.; Li, D.; Cui, B.; Liu, D. Chemically Functionalized Penta-stanene Monolayers for Light Harvesting with High Carrier Mobility. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 21763–21769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, H.; Meng, M.; Chen, C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Dang, W.; Tan, C.; Liu, Y.; Yin, J.; et al. High electron mobility and quantum oscillations in non-encapsulated ultrathin semiconducting Bi2O2Se. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamilselvan, M.; Bhattacharyya, A.J. Antimony sulphoiodide (SbSI), a narrow band-gap non-oxide ternary semiconductor with efficient photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 105980–105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedukondalu, N.; Shafique, A.; Rakesh Roshan, S.C.; Barhoumi, M.; Muthaiah, R.; Ehm, L.; Parise, J.B.; Schwingenschlögl, U. Lattice Instability and Ultralow Lattice Thermal Conductivity of Layered PbIF. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 40738–40748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Biswas, K. Carrier Self-trapping and Luminescence in Intrinsically Activated Scintillator: Cesium Hafnium Chloride (Cs2HfCl6). J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 12187–12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.-H.; Singh, D.J. Enhanced Born charge and proximity to ferroelectricity in thallium halides. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 144114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Longo, G. Prospect for Bismuth/Antimony Chalcohalides-Based Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2306075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.S.; Álvarez, Á.L.; Medaille, A.G.; Caño, I.; Navarro-Güell, A.; Álvarez, C.L.; Cazorla, C.; Ferrer, D.R.; Li-Kao, Z.J.; Saucedo, E.; et al. Parallel exploration of the optoelectronic properties of (Sb,Bi)(S,Se)(Br,I) chalcohalides. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 31727–31739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Rabe, K.M.; Vanderbilt, D. Negative piezoelectric response of van der Waals layered bismuth tellurohalides. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Hua, C.; Lu, Y.; Tao, X. A density functional theory study of two-dimensional bismuth selenite: Layer-dependent electronic, transport and optical properties with spin–orbit coupling. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, F.; Nie, J.; Yu, H.; Yue, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, C. Enhancing Piezo-Catalytic Hydrogen Evolution on BiOCl through UV Irradiation. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 9195–9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Xu, H.; He, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, M. Piezoelectric polarization of BiOCl via capturing mechanical energy for catalytic H2 evolution. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 31, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhao, X.-G.; Biswas, K.; Singh, D.J.; Zhang, L. Bismuth and antimony-based oxyhalides and chalcohalides as potential optoelectronic materials. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 2044–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Ming, W.; Du, M.-H. Bismuth chalcohalides and oxyhalides as optoelectronic materials. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyd, J.; Scuseria, G.E.; Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 8207–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.-C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt, D. Berry-phase theory of proper piezoelectric response. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2000, 61, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.C.; Kim, Y.G.; Kim, M.Y.; Koh, J.D.; Park, B.S.; Kim, W.T. Optical properties of undoped and chromium-doped VA-VIA-VIIA single crystals. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 6113–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-A.; Kim, M.-Y.; Lim, J.-Y.; Park, B.-S.; Koh, J.-D.; Kim, W.-T. Optical Properties of Undoped and V-Doped VA−VIA−VIIA Single Crystals. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 1995, 187, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.; Perlov, C.; Wooten, F. Electronic properties of BiSeI and BiSeBr. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1982, 15, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Wang, X.; Lian, W.; Huang, J.; Wei, Q.; Huang, M.; Yin, Y.; Jiang, C.; Yang, S.; Xing, G.; et al. Hydrothermal deposition of antimony selenosulfide thin films enables solar cells with 10% efficiency. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijtens, T.; Bush, K.A.; Prasanna, R.; McGehee, M.D. Opportunities and challenges for tandem solar cells using metal halide perovskite semiconductors. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.E. Origin of ferroelectricity in perovskite oxides. Nature 1992, 358, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.J. Optical properties of cubic and rhombohedral GeTe. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 203101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, A.; Spaldin, N.A. Strong-correlation effects in Born effective charges. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 045111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistoni, O.; Barone, P.; Cappelluti, E.; Benfatto, L.; Mauri, F. Giant effective charges and piezoelectricity in gapped graphene. 2D Mater. 2019, 6, 045015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Tang, G.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wang, R.-T.; Mizuseki, H.; Kawazoe, Y.; Nara, J.; Geng, W.T. High-Throughput Computational Screening of Two-Dimensional Semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 11581–11594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.-W.; Park, H.S. Mechanical properties of single-layer black phosphorus. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 385304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Han, C.; Dong, S.; Niu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Liu, H. Stability, Electronic, and Piezoelectric Properties of H- and F-Functionalized BP Sheets. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2025, 262, 2400361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, N.; Joshi, R.; Lee, G.-H. Mechanical properties of two-dimensional materials and their applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2019, 52, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Two-dimensional materials: From mechanical properties to flexible mechanical sensors. InfoMat 2020, 2, 1077–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, A.K.; Hoang, A.T.; Xu, D.; Hong, J.; Kim, B.J.; Ji, S.; Ahn, J.-H. 2D Materials in Flexible Electronics: Recent Advances and Future Prospectives. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 318–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Gong, K.; Li, Y.; Ding, B.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Lin, S. Flexible 2D Materials beyond Graphene: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Small 2022, 18, 2105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonsky, M.N.; Zhuang, H.L.; Singh, A.K.; Hennig, R.G. Ab Initio Prediction of Piezoelectricity in Two-Dimensional Materials. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9885–9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Ali, T.; Pilz, J.; Schäffner, P.; Kratzer, M.; Teichert, C.; Stadlober, B.; Coclite, A.M. Piezoelectric Properties of Zinc Oxide Thin Films Grown by Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2020, 217, 2000319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Lei, S.Y.; Xu, F.; Chen, J.; Wan, N.; Huang, Q.A.; Sun, L.T. Realization of a piezoelectric quantum spin Hall phase with a large band gap in MBiH (M = Ga and In) monolayers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 25683–25691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Deng, Z.; Li, S.; Lv, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, G.; Hong, J. First-principles insights into the ferroelectric, dielectric, and piezoelectric properties of polar Pca21 SbN. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 174110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor-A-Alam, M.; Nolan, M. Negative Piezoelectric Coefficient in Ferromagnetic 1H-LaBr2 Monolayer. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cohen, R.E. Origin of Negative Longitudinal Piezoelectric Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 207601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.; Islam, M.T.; Rasadujjaman, M.; Hossain, M.A. Mechanical, optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of MoSI: A DFT insights. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2026, 209, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Fujisawa, J.-I.; Segawa, H.; Yamashita, K. Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Lead Iodide Perovskite Featuring Zero Dipole Moment Guanidinium Cations: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 4694–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Fujisawa, J.-I.; Segawa, H.; Yamashita, K. Small Photocarrier Effective Masses Featuring Ambipolar Transport in Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite: A Density Functional Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 4213–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, L.E.; Teles, L.K.; Scolfaro, L.M.R.; Castineira, J.L.P.; Rosa, A.L.; Leite, J.R. Structural, electronic, and effective-mass properties of silicon and zinc-blende group-III nitride semiconductor compounds. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 165210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.H.; Yadav, V.K.; Singh, J.K. Recent Advances in the Carrier Mobility of Two-Dimensional Materials: A Theoretical Perspective. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 14203–14211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Li, W.-Y.; Xiao, X.-F.; Liu, Y.-C.; Geng, W.T.; Wang, V. A comparative first-principles study of the electronic and excitonic properties of 2H-CrX2 (X = S, Se, Te) monolayers. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostructures 2025, 171, 116237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Bie, M.; Shang, J.; Tang, X.; Kou, L. Janus transition metal dichalcogenides: A superior platform for photocatalytic water splitting. J. Phys. Mater. 2020, 3, 022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Neal, A.T.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Xu, X.; Tománek, D.; Ye, P.D. Phosphorene: An Unexplored 2D Semiconductor with a High Hole Mobility. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 4033–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-Q.; Ma, Q.-R.; Liu, B.; Yu, Z.-L.; Yang, J.; Cai, M.-Q. Layer-dependent transport and optoelectronic property in two-dimensional perovskite: (PEA)2PbI4. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 8677–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| a (Å) | h (Å) | Bi-X (Å) | Bi-Y (Å) | PBE + SOC (eV) | HSE06 + SOC (eV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | 4.187 | 3.464 | 2.872 | 3.082 | 0.96 | 1.62 |

| BiSeI | 4.270 | 3.643 | 2.883 | 3.269 | 0.87 | 1.45 |

| BiTeBr | 4.345 | 3.570 | 3.059 | 3.098 | 0.83 | 1.39 |

| BiTeI | 4.422 | 3.776 | 3.071 | 3.286 | 0.65 | 1.18 |

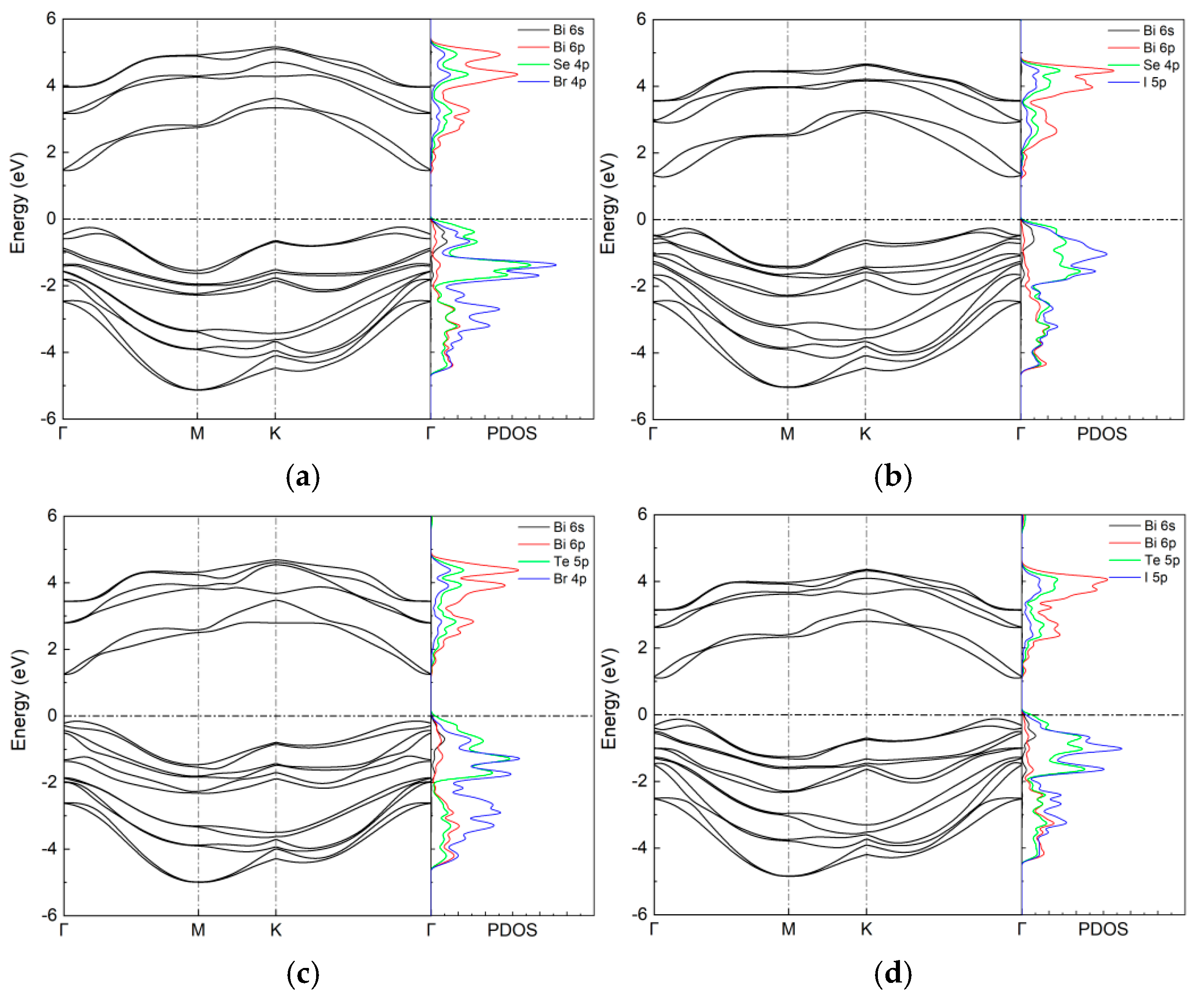

(e) | (e) | (e) | ԑ0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | 5.31 | −2.90 | −2.41 | 9.92 |

| BiSeI | 5.56 | −3.34 | −2.21 | 10.70 |

| BiTeBr | 5.05 | −2.22 | −2.83 | 9.88 |

| BiTeI | 5.30 | −2.65 | −2.64 | 10.24 |

| C11 (N/m) | C12 (N/m) | Y2D (N/m) | ν | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | 31.37 | 9.03 | 28.8 | 0.29 |

| BiSeI | 30.40 | 9.40 | 27.5 | 0.31 |

| BiTeBr | 28.10 | 7.12 | 26.3 | 0.25 |

| BiTeI | 26.85 | 7.27 | 24.9 | 0.27 |

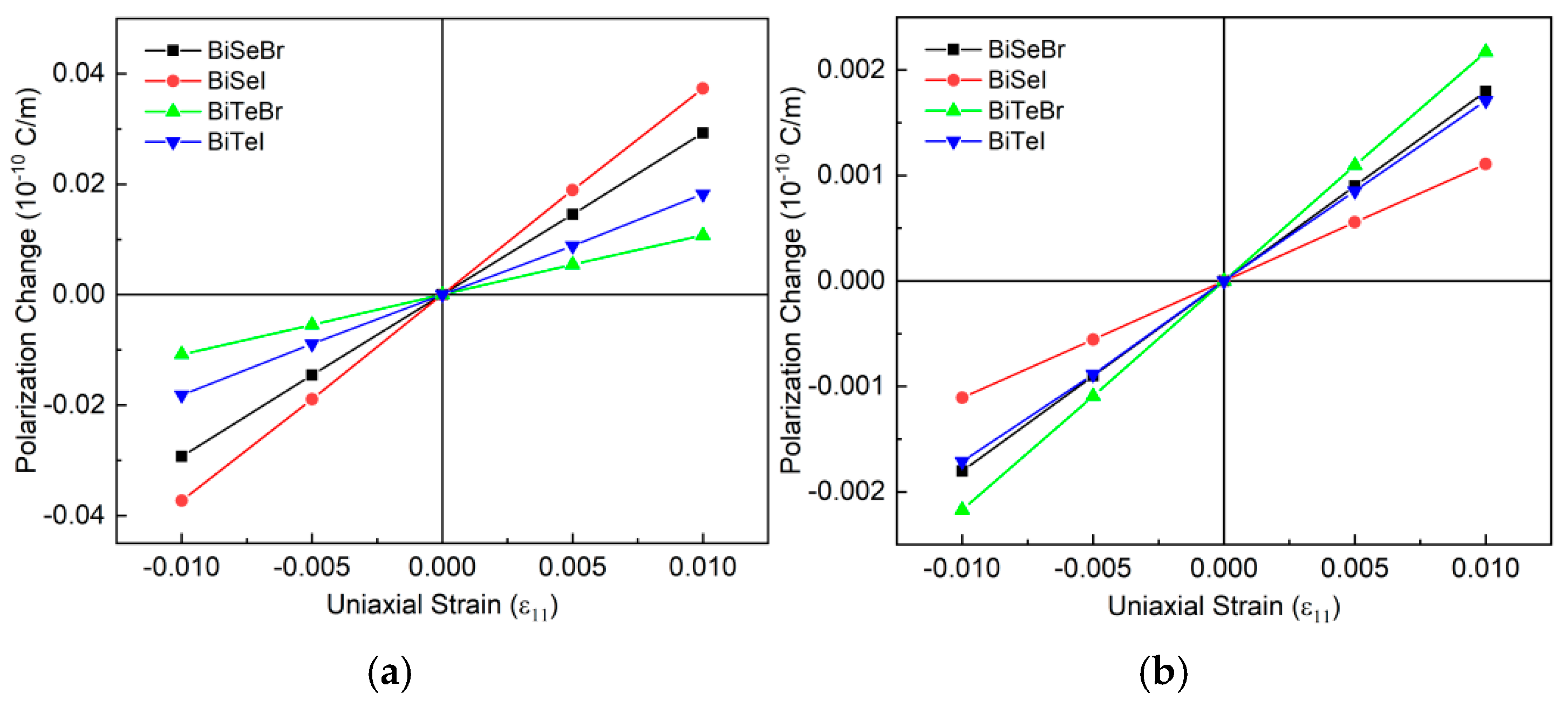

| e11 (10−10 C/m) | e31 (10−10 C/m) | d11 (pm/V) | d31 (pm/V) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | 2.94 | 0.18 | 13.16 | 0.45 |

| BiSeI | 3.73 | 0.11 | 17.76 | 0.28 |

| BiTeBr | 1.08 | 0.22 | 5.15 | 0.63 |

| BiTeI | 1.81 | 0.17 | 9.24 | 0.50 |

(10−10 C/m) | (10−10 C/m) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | 1.04 | 1.89 | 0.039 | 0.111 | −0.150 |

| BiSeI | 1.91 | 1.82 | 0.047 | 0.108 | −0.155 |

| BiTeBr | −0.42 | 1.50 | 0.016 | 0.117 | −0.135 |

| BiTeI | 0.40 | 1.41 | 0.025 | 0.120 | −0.144 |

| Effective Mass (m0) | C11 (N/m) | E1 (eV) | Mobility (cm2 V−1 s−1) | Relaxation Time (fs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiSeBr | Electron | 0.20 | 31.37 | 3.53 | 1342.2 | 152.8 |

| Hole | 0.45 | 31.37 | 1.35 | 1812.7 | 464.4 | |

| BiSeI | Electron | 0.23 | 30.40 | 3.86 | 822.5 | 107.7 |

| Hole | 0.35 | 30.40 | 2.41 | 911.2 | 181.6 | |

| BiTeBr | Electron | 0.15 | 28.10 | 3.12 | 2736.1 | 233.7 |

| Hole | 0.40 | 28.10 | 1.18 | 2689.9 | 612.6 | |

| BiTeI | Electron | 0.16 | 26.85 | 3.42 | 1912.3 | 174.2 |

| Hole | 0.37 | 26.85 | 2.01 | 1035.3 | 218.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Han, C.; Niu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, V. Large Piezoelectric Response and High Carrier Mobilities Enhanced via 6s2 Hybridization in Bismuth Chalcohalide Monolayers. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241877

Shi J, Han C, Niu H, Zhu Y, Liu Y, Wang V. Large Piezoelectric Response and High Carrier Mobilities Enhanced via 6s2 Hybridization in Bismuth Chalcohalide Monolayers. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241877

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jing, Chang Han, Haibo Niu, Youzhang Zhu, Yachao Liu, and Vei Wang. 2025. "Large Piezoelectric Response and High Carrier Mobilities Enhanced via 6s2 Hybridization in Bismuth Chalcohalide Monolayers" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241877

APA StyleShi, J., Han, C., Niu, H., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., & Wang, V. (2025). Large Piezoelectric Response and High Carrier Mobilities Enhanced via 6s2 Hybridization in Bismuth Chalcohalide Monolayers. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241877