Sequential Ni-Pt Decoration on Co(OH)2 via Microwave Reduction for Highly Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Noble Metal-Decorated Co(OH)2 Electrocatalysts

2.2.1. Synthesis of Porous Co(OH)2 Precursors

2.2.2. Synthesis of M@Co(OH)2 (M = Ni, Pt, Etc.) Noble Metal Electrocatalysts

2.2.3. Synthesis of 2M@Co(OH)2 (M = Ni, Pt) Noble Metal Catalysts

- (1)

- Synthesis of PtNi Co-Decorated Co(OH)2 Catalysts

- (2)

- Synthesis of Pt-Ni@Co(OH)2 Cobalt Hydroxide Catalysts with Sequential Pt-then-Ni Loading

- (3)

- Synthesis of Ni-Pt@Co(OH)2 Cobalt Hydroxide Catalysts with Sequential Ni-then-Pt Loading

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Performance Characterization

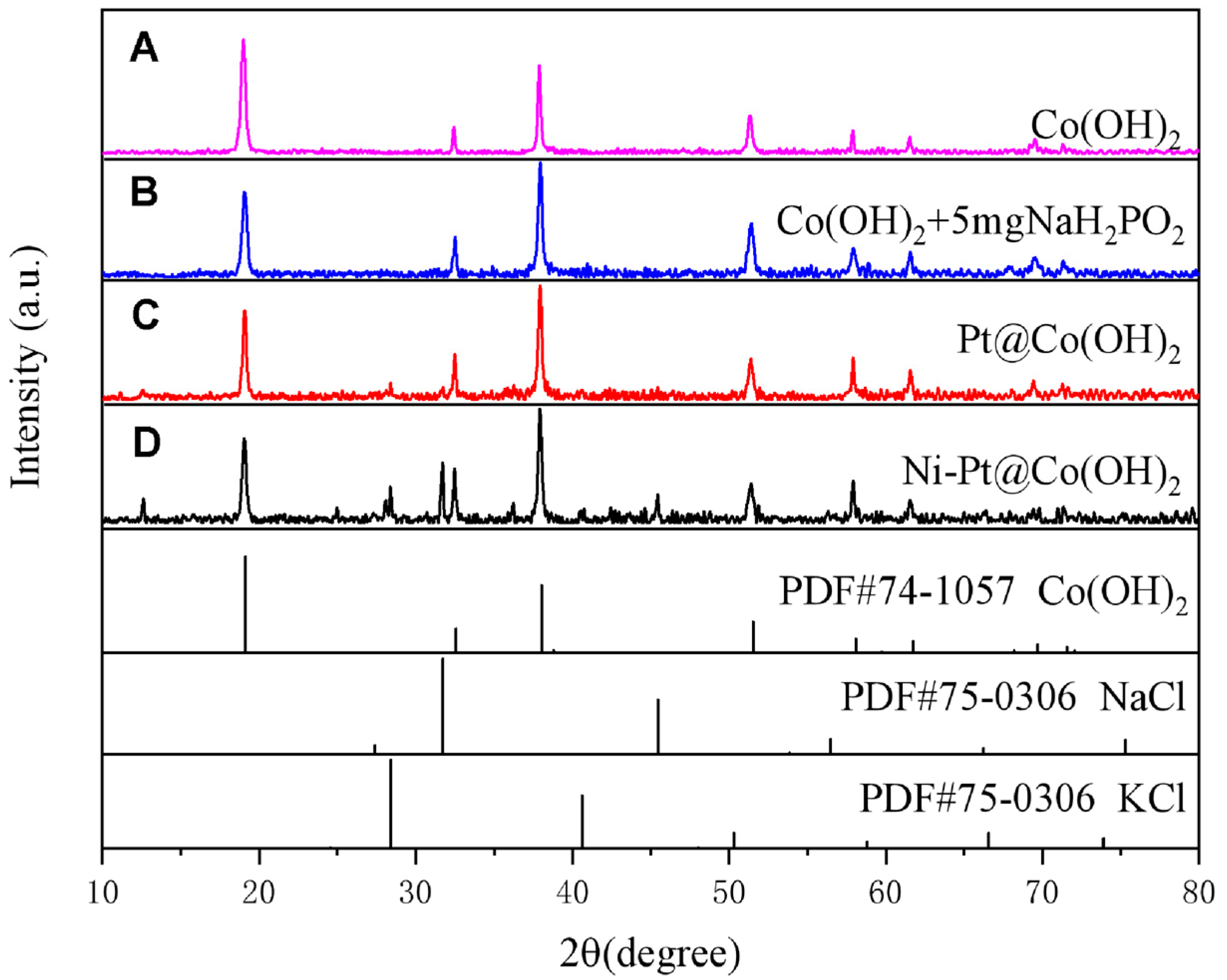

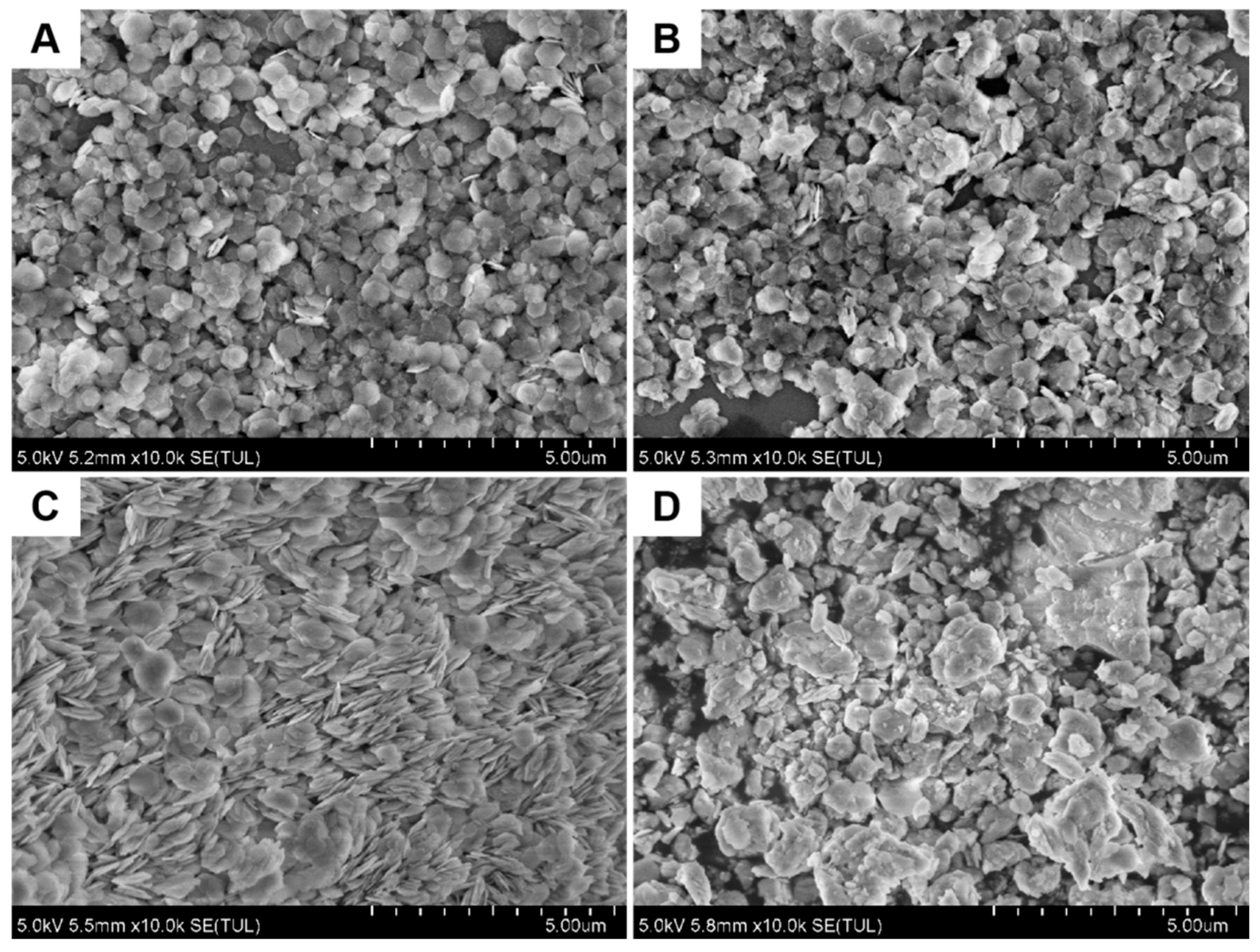

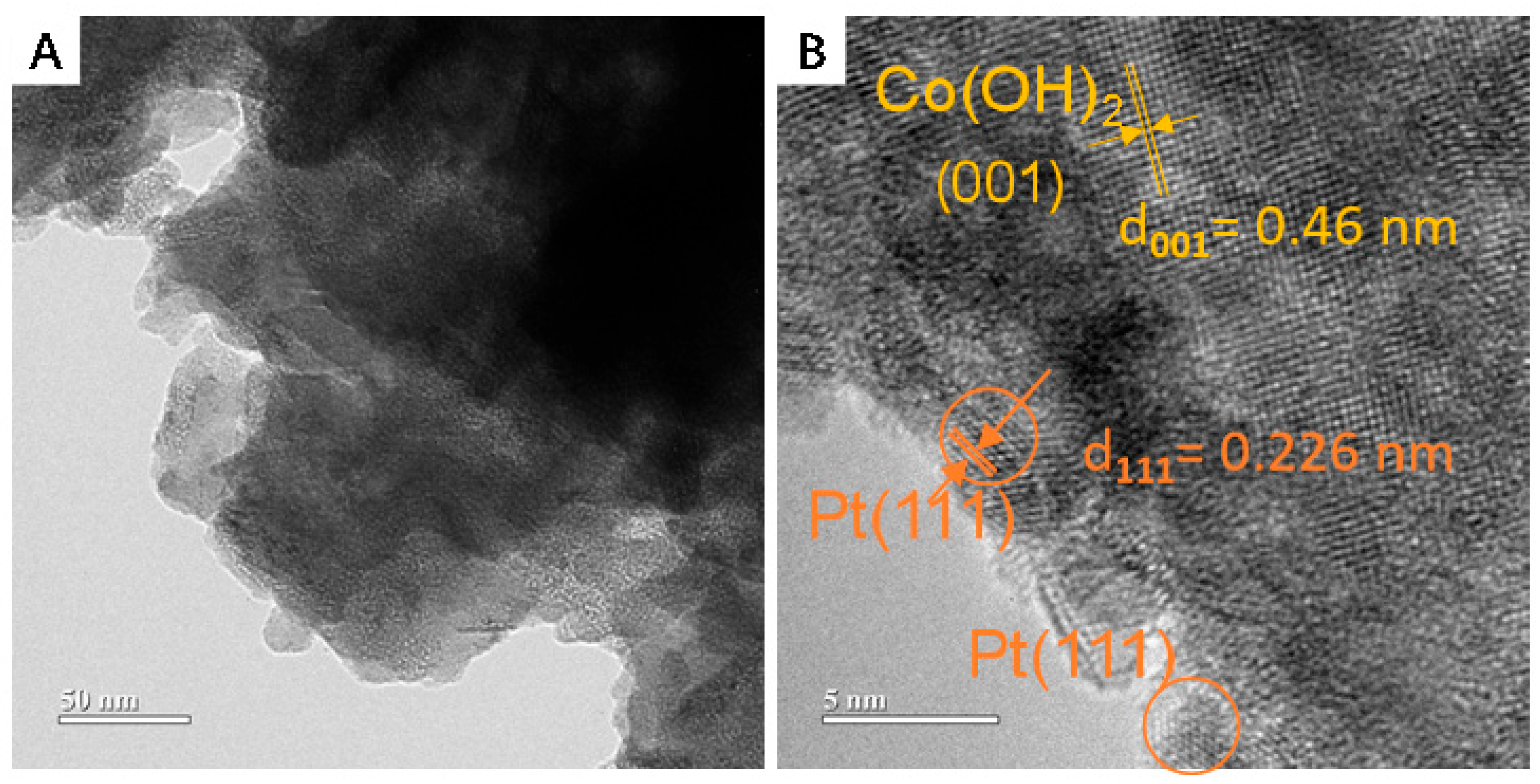

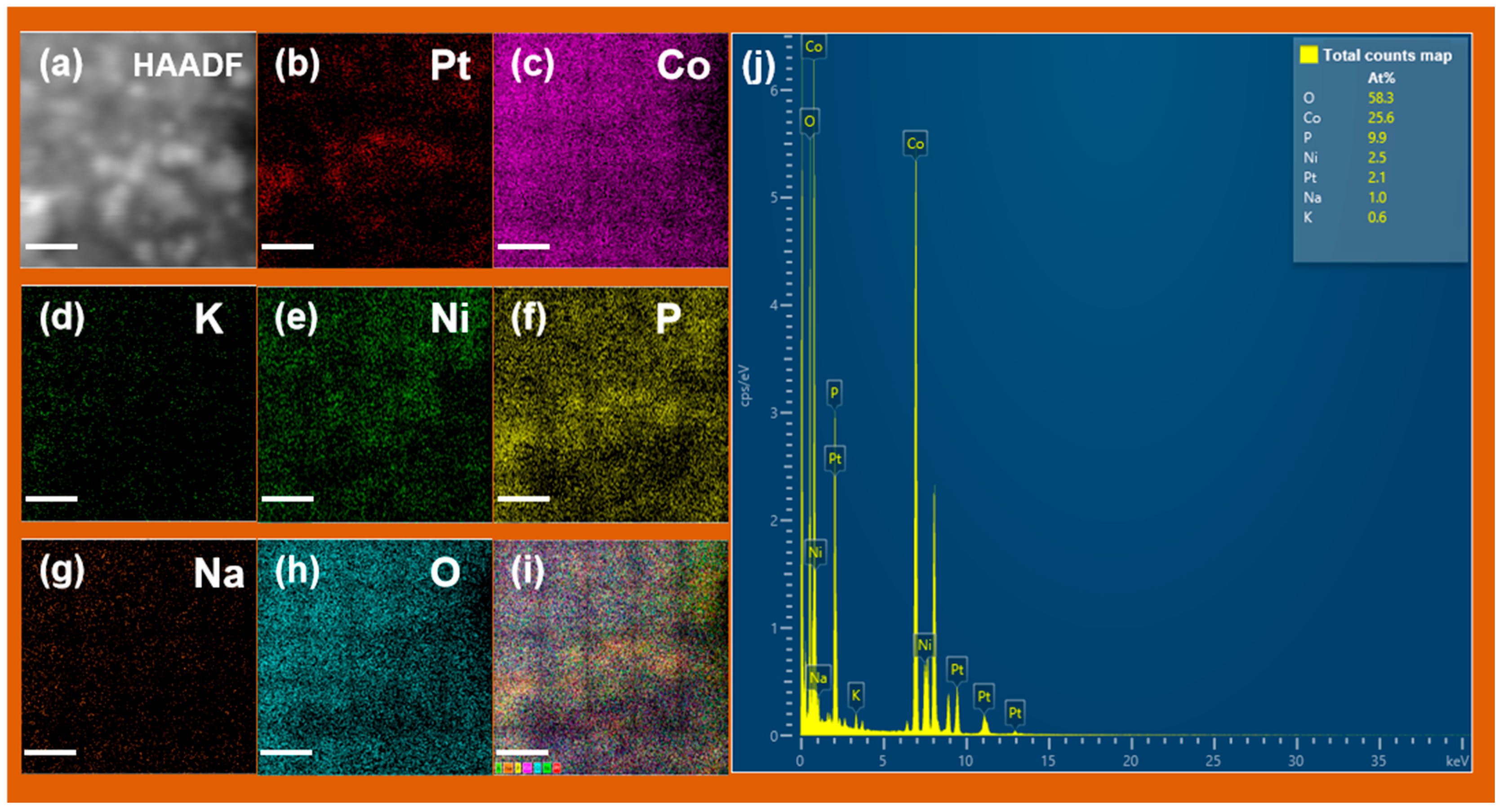

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, G.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, G.; Sun, B.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Lan, Y. Recent advancements in noble-metal electrocatalysts for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Zhong, Q.; Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Tang, J. Sustainable and cost-efficient hydrogen production using platinum clusters at minimal loading. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bao, Y.; Ye, R.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Z.; Kang, W.; Aidarova, S.B. Recent progress and perspective of electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 2104–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; He, Z.; Yan, M.; Xiang, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Li, J. Facet-Tailored Co3O4 as Electronic Regulator and Stabilizing Support for Ru Nanocluster: Toward Efficient Alkaline HER. Energy Environ. Mater. 2025, e70172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ke, J.; Zhong, C.; Tan, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Song, H.; Du, L.; et al. Surface strain effect on electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction of Pt-based intermetallics. Acs Catal. 2024, 14, 2917–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qiao, Y.; He, H.; Chen, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Pan, L.; Feng, Z.; Tan, R. Rapid synthesis of PtRu nanoparticles on aniline-modified SWNTs in EMSI engineering for enhanced alkaline water electrolysis. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Du, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, F. Electroreduction-driven distorted nanotwins activate pure Cu for efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Mai, J.; Hu, K.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, F.; Liu, X. Recent advances in electrocatalysts for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Rare Metals 2025, 44, 2208–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Tang, H.; Wang, Y. Pt Nanoparticles Supported on N-Doped TiO2/C Composite Supports for Fuel Cell Catalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1042, 184103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, L.; Shen, T.; Jiang, K.; Sun, H.; Yan, Z.; Chen, X. Sub-2 nm platinum nanocluster decorated on yttrium hydroxide as highly active and robust self-supported electrocatalyst for industrial-current alkaline hydrogen evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 702, 138904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalji, M.R.; Mahmoudi, F.; Bachas, L.G.; Park, C. MXene-Based Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting: Material Design, Surface Modulation, and Catalytic Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tan, X.; Ma, Y.; Obisanya, A.A.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, D. Recent Progress in Cobalt—Based Electrocatalysts for Efficient Electrochemical Nitrate Reduction Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, C. Cobalt oxide-based catalysts for acidic oxygen evolution reactions. Aust. J. Chem. 2025, 78, CH25104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Gu, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Z.; Qiang, J.; Song, Z.; Du, Y. Self-supported Fe, Mn-CoCH/NF electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 703, 139149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Xi, W.; Wang, P.; Wu, T.; Liu, P.; Gao, B.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, B. In-situ construction of 2D β-Co(OH)2 nanosheets hybridized with 1D N-doped carbon nanotubes as efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jin, B.; Li, Y. A snowflake hexagonal arrangement of β-Co(OH)2/Co(OH)F: A strategy to improve polysulfide adsorption and shuttle effect in Li-S batteries. J. Energy Storage 2025, 123, 116863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Qiu, F.; Zhu, S.; Li, S.; Lyu, Z.; Xu, S.; Hong, K.; Wang, Y. Noble metal confined in defect-enriched NiCoO2 with synergistic effects for boosting alkaline electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 686, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Qian, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xiong, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, W. Interfacial Electronic Modulation in Heterostructured OER Electrocatalysts: A Review. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 23854–23882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Ying, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, H. Transition metal-doped modification of lattice defects in formaldehyde catalysts- Controlling the specific surface area and mass transfer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 681, 161319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rui, Y.; Zhu, H.; Pan, D.; Gu, Y.; Wang, T. Efficient overall water splitting electrode regulated by Pt nanodots modified NiCo-carbonate hydroxide nanowires on porous rGO matrix. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 180, 151788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan, S.; Dh, H.N.; Karmakar, A.; Kundu, S. Recent advancement of 2D bi-metallic hydroxides with various strategical modification for the sustainable hydrogen production through water electrolysis. ES Mater. Manuf. 2023, 19, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Suo, N.; Han, X.; He, X.; Dou, Z.; Lin, Z.; Cui, L. Tuning the morphology and electron structure of metal-organic framework-74 as bifunctional electrocatalyst for OER and HER using bimetallic collaboration strategy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 865, 158795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, W.; Wu, Y.; Chu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, S.; Liu, C.; Che, G.; Liu, G. Unveiling the Dual Active Sites of Ni/Co(OH)2—Ru Heterointerface for Robust Electrocatalytic Alkaline Seawater Splitting. Small 2025, 21, 2410086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, F.; Lv, Y.; Ran, N.; Zhou, W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, J. Scalable synthesis and tensile-strain modulation of NiPt1% alloy with enhanced large-current hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2026, 381, 125809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wei, G.; Chen, H.; Sun, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X. Enhancing carbon activity in C@hcp-NiPt/NF electrocatalyst for pH-universal hydrogen evolution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 686, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Yang, Z.; Fang, B.; Sun, Q.; Feng, Y.; Yao, J. Boosting redox activity and charge transfer kinetics in hollow CoNiS/CoNi-LDH heterostructures via interface engineering for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 32777–32783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Yang, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, G.; Ru, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, B. Heterojunction engineering of NiC/NiPt promoting charge remigration on the Pt site with efficient acid hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 29070–29078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yue, F.; Tan, H.; Zeng, K.; Fan, W.; Gong, K.; Wu, X.; Dai, C.; Chen, W.; Tan, X. Tailoring the Effects of Spin State and Intermediate Hydrogen Adsorption on NiPt/Ni Bridge Sites toward Robust Acidic Water Electrolysis. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 13956–13964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; Lan, J.; Yan, Y.; Ma, J.; Sang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M. Tailoring NiPt1 single-atom alloy nanoclusters by embedded Ni3ZnC0.7 to accelerate alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, S.; Qing, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Understanding the Roles and Regulation Methods of Key Adsorption Species on Ni—Based Catalysts for Efficient Hydrogen Oxidation Reactions in Alkaline Media. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Dai, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, S. Ni@ Pt core-shell nanoparticles: Synthesis, structural and electrochemical properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R.R.; Tolmachev, Y.V. Electrochemical properties of Pt coatings on Ni prepared by atomic layer deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 156, A37–A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalysts | Pt[wt%]1 | Pt[wt%]2 | Pt[wt%]3 | Average Pt Content [wt%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt@Co(OH)2 | 5.6926% | 5.9932% | 5.5263% | 5.7374% |

| Ni-Pt@Co(OH)2 | 5.6653% | 5.2463% | 5.1120% | 5.3412% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Cao, G.; Wu, X.; Jia, B.; Qu, X.; Qin, M. Sequential Ni-Pt Decoration on Co(OH)2 via Microwave Reduction for Highly Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241876

Liu L, Liu H, Chen Z, Cao G, Wu X, Jia B, Qu X, Qin M. Sequential Ni-Pt Decoration on Co(OH)2 via Microwave Reduction for Highly Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241876

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Luan, Hongru Liu, Zikang Chen, Genghua Cao, Xiaoyu Wu, Baorui Jia, Xuanhui Qu, and Mingli Qin. 2025. "Sequential Ni-Pt Decoration on Co(OH)2 via Microwave Reduction for Highly Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241876

APA StyleLiu, L., Liu, H., Chen, Z., Cao, G., Wu, X., Jia, B., Qu, X., & Qin, M. (2025). Sequential Ni-Pt Decoration on Co(OH)2 via Microwave Reduction for Highly Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241876