Synthesis and Characterization of Eco-Engineered Hollow Fe2O3/Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres: Evaluating Structural, Optical, Antibacterial, and Lead Adsorption Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of the Molecular Precursor and α-Fe2O3/C Hollow Spheres

2.3. Adsorbent Characterization

2.4. Antimicrobial Testing

2.5. Adsorption Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fe2O3/C Composite Characterization

3.1.1. X-Ray Powder Diffraction Analysis

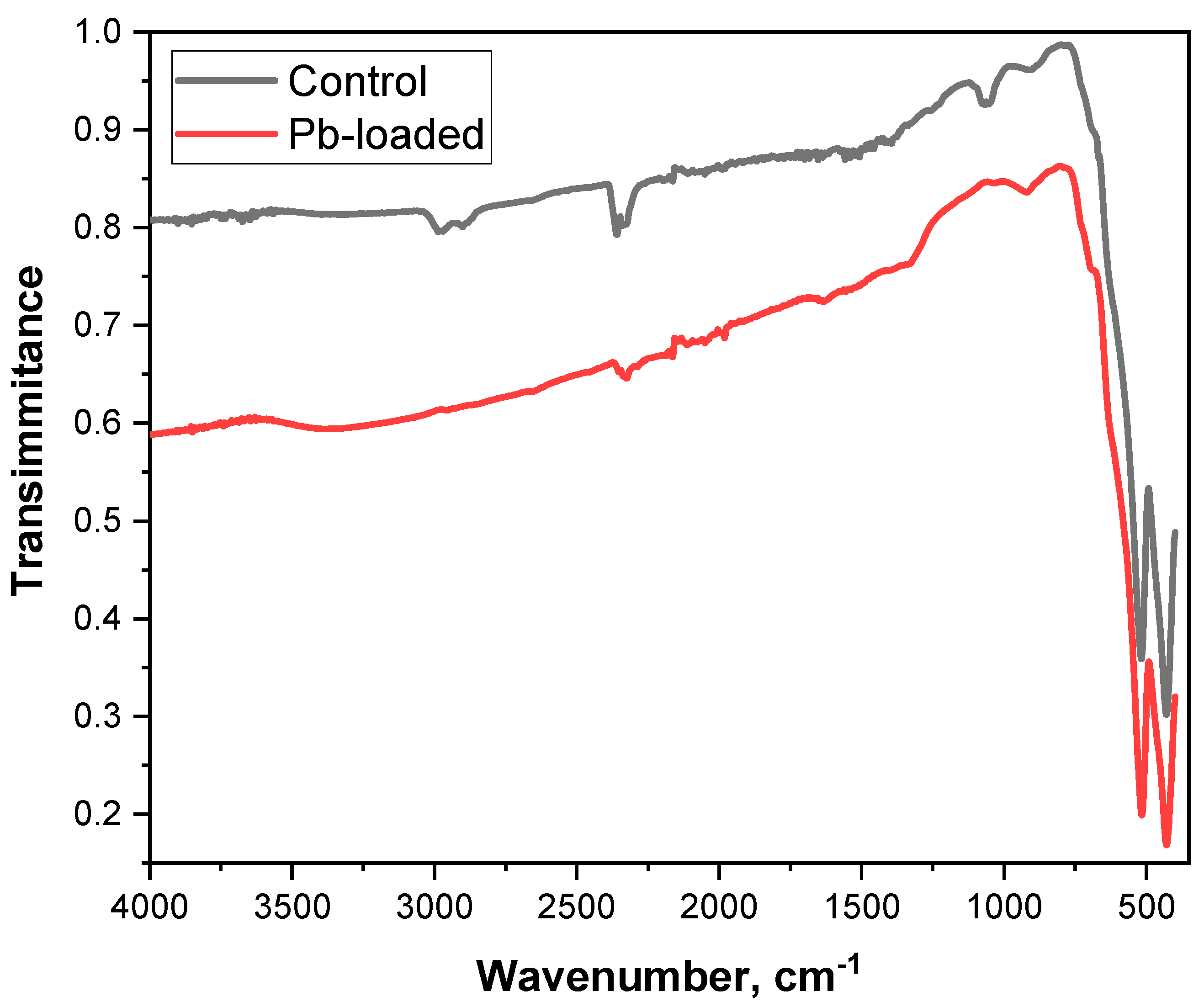

3.1.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis

3.1.3. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis

3.1.4. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis

3.1.5. Antimicrobial Activity

3.1.6. Optical Analysis

3.2. Adsorption Capacity of Fe2O3/C for Lead Ions

3.2.1. Effect of Experimental Parameters on Lead Adsorption (pH, Time and Lead Concentration)

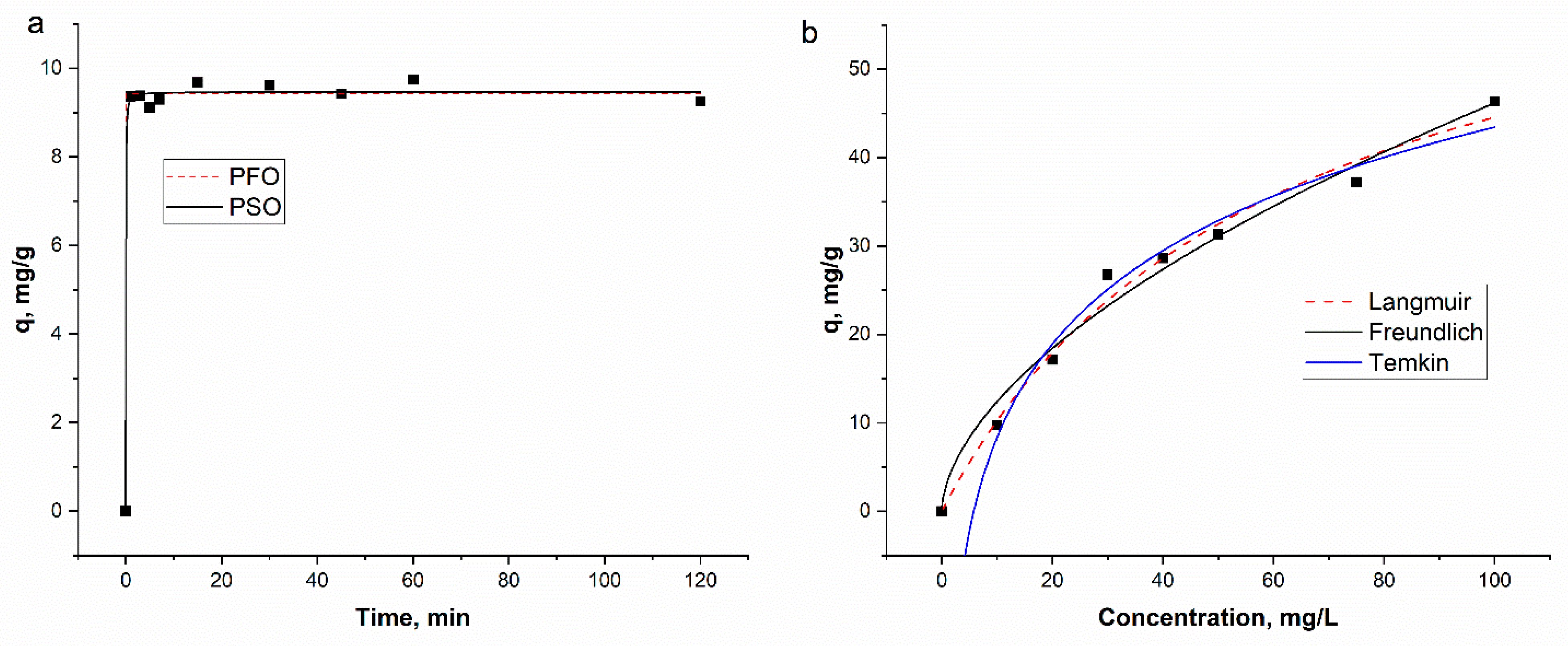

3.2.2. Kinetics and Equilibrium Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, K.; Alasmary, Z. Lead (Pb) Contamination in Soil and Plants at Military Shooting Ranges and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2025, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Mahmood, A.; Shahid, S.A.; Shah, S.S.; Khalid, A.M.; McKay, G. Sorption of lead from aqueous solution by chemically modified carbon adsorbents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 138, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-wahaab, B.A.; El-Shwiniy, W.H.; Alrowais, R.; Nasef, B.M.; Said, N. Adsorption of Lead (Pb(II)) from Contaminated Water onto Activated Carbon: Kinetics, Isotherms, Thermodynamics, and Modeling by Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, S.; Baskar, A.; Geevarghese, D.M.; Ali, M.N.V.S.; Bahubali, P.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I.; Senatov, F.; Koppala, S.; et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects in plants: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2022, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Mitra, P.; Sharma, P. Unmasking Lead Exposure and Neurotoxicity: Epigenetics, Extracellular Vesicles, and the Gut-Brain Connection. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2025, 40, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouida, L.; Rafatullah, M.; Kerrouche, A.; Qutob, M.; Alosaimi, A.M.; Alorfi, H.S.; Hussein, M.A. A Review on Cadmium and Lead Contamination: Sources, Fate, Mechanism, Health Effects and Remediation Methods. Water 2022, 14, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, R.; Dash, P.; Panda, P.K.; Yang, P.C. A Breakthrough in Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment: The Incredible Potential of g-C3N4/Titanate Perovskite-Based Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda-Mbanga, B.G.; Onotu, O.P.; Tywabi-Ngeva, Z. Advantages of the reuse of spent adsorbents and potential applications in environmental remediation: A review. Green Anal. Chem. 2024, 11, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.C.; Choo, Y.L.; Koo, C.H.; Pang, Y.L.; Lai, S.O. Adsorptive membranes for heavy metal removal—A mini review. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2157, 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albqmi, M.; Frontistis, Z.; Raji, Z.; Karim, A.; Karam, A.; Khalloufi, S. Adsorption of Heavy Metals: Mechanisms, Kinetics, and Applications of Various Adsorbents in Wastewater Remediation—A Review. Waste 2023, 1, 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, B.T.; Anh, T.T. Controlled synthesis of various Fe2O3 morphologies as energy storage materials. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Breakwell, C.; Foglia, F.; Tan, R.; Lovell, L.; Wei, X.; Wong, T.; Meng, N.; Li, H.; Seel, A.; et al. Selective ion transport through hydrated micropores in polymer membranes. Nature 2024, 635, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xia, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Xu, H.; Huang, L.; He, M. Ionic liquid assisted synthesis and photocatalytic properties of α-Fe2O3 hollow microspheres. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 6468–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.W.; Zhu, Y.J.; Microspheres, M. Monodisperse α-Fe2O3 Mesoporous Microspheres: One-Step NaCl-Assisted Microwave-Solvothermal Preparation, Size Control and Photocatalytic Property. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Dong, L. One-step synthesis and properties of urchin-likePS/α-Fe2O3 composite hollow microspheres. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 435608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, I.; Alsaiari, R.A.; Morsy, M.; Rizk, M.A. Autonomous sampling of α-Fe2O3 hollow microspheres with carbon-stabilized defects: Calcination-tuned humidity sensor performance. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2025, 80, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, N.M.; Gomaa, I.; El-Moemen, A.A.; Anwar, Z.M. Adsorption of Ponceau Xylidine dye by synthesised Mn2O3 nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 103, 9616–9632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test Protocol. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2009, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Selective Reporting of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Results: A Primer for Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2016.

- Dudenko, D.V.; Williams, P.A.; Hughes, C.E.; Antzutkin, O.N.; Velaga, S.P.; Brown, S.P.; Harris, K.D.M. Exploiting the synergy of powder x-ray diffraction and solid-state NMR spectroscopy in structure determination of organic molecular solids. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 12258–12265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosny, N.M.; Gomaa, I.; Elmahgary, M.G.; Ibrahim, M.A. ZnO doped C: Facile synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic degradation of dyes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Quan, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y. Photocatalytic reaction by Fe(III)–citrate complex and its effect on the photodegradation of atrazine in aqueous solution. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2008, 197, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P.S.; Go, G.H.; Lee, W.J. Facile growth of hierarchical hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanopetals on FTO by pulse reverse electrodeposition for photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10469–10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.G.; Gleeson, M.A.; Lauritsen, J.V.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Niemantsverdriet, J.W.H.; Weststrate, C.J.K.-J. Iron carbide formation on thin iron films grown on Cu(1 0 0): FCC iron stabilized by a stable surface carbide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 585, 152684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy C. D. Wanger, W. M. Riggs, L. E. Davis, J. F. Moulder and G. E.Muilenberg Perkin-Elmer Corp., Physical Electronics Division, Eden Prairie, Minnesota, USA, 1979. 190 pp. $195. Surf. Interface Anal. 1981, 3, v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Hayes, P. Analysis of XPS spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions in oxide materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Pei, Z.; Lv, M.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, S. Polypyrrole-Coated Low-Crystallinity Iron Oxide Grown on Carbon Cloth Enabling Enhanced Electrochemical Supercapacitor Performance. Molecules 2023, 28, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, P.; Sullivan, J.L. A study of the core level electrons in iron and its three oxides by means of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1983, 16, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, G.B.; Phillips, R.J. Relationships between the carbon-oxygen stretching frequencies of carboxylato complexes and the type of carboxylate coordination. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1980, 33, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, C.G.; Bradley, D.C.; Lewis, J.; Thomas, I.M. 510. The infrared spectra of some metal alkoxides, trialkylsilyloxides, and related silanols. J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 1961, 32, 2601–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwaar, S.; Altaf, F.; Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H.; Siddiqi, E.H.; Soufan, W.; Zaman, W. Biogenic synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Eucalyptus globulus Leaf Extract and its impact on germination and Phytochemical composition of Lactuca sativa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozali, M.L.H.; Ahmad, Z.; Isa, M.I.N. Interaction between Carboxy Methylcellulose and Salicylic Acid Solid Biopolymer Electrolytes. Adv. Mat. Res. 2015, 1107, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Morales, A.C.; Ryan, J.; Misovich, M.V.; Hettiyadura, A.P.S.; Rivera-Adorno, F.; Tomlin, J.M.; Darmody, A.; Linn, B.N.; Lin, P.; et al. Molecular investigation of the multi-phase photochemistry of Fe(III)–citrate in aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2023, 25, 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraja, S.; Balaji, D.S.; Bedre, M.D.; Raghunandan, D.; Swamy, P.M.P.; Venkataraman, A. Solvothermal synthesis and characterization of acicular α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2011, 34, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, J.J.; Chapados, C. Infrared spectroscopy of aqueous carboxylic acids: Malic acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 6452–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Muršec, M.; Šuštar, V.; Kristl, J. Application of thermogravimetric analysis for the evaluation of organic and inorganic carbon contents in agricultural soils. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 123, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Xu, S.; Shao, X.; Wen, Y.; Shi, X.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z. Carbon coating on metal oxide materials for electrochemical energy storage. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 502004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Jiang, Z.; Gai, C.; Barrón, V.; Torrent, J.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Q. Re-Visiting the Quantification of Hematite by Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy. Minerals 2022, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, A.M.; Pitman, K.M.; Goncharov, A.F.; Speck, A.K. Optical constants of silicon carbide for astrophysical applications. ii. extending optical functions from infrared to ultraviolet using single-crystal absorption spectra. Astrophys. J. 2009, 696, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, A.; Manteghian, M.; Kazemzadeh, H. Removing lead from aqueous solution by activated carbon nanoparticle impregnated on lightweight expanded clay aggregate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbar, B.; Alem, A.; Marcotte, S.; Pantet, A.; Ahfir, N.D.; Bizet, L.; Duriatti, D. Experimental investigation on removal of heavy metals (Cu2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+) from aqueous solution by flax fibres. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 109, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinicovscaia, I.; Yushin, N.; Rodlovskaya, E.; Kamanina, I. Biosorption of lead ions by cyanobacteria Spirulina platensis: Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamic study. Nova Biotechnol. Chim. 2017, 16, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yu, J.; Liao, H.; Zhu, W.; Ding, P.; Zhou, J. Adsorption of Lead (II) from Aqueous Solution with High Efficiency by Hydrothermal Biochar Derived from Honey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherono, F.; Mburu, N.; Kakoi, B. Adsorption of lead, copper and zinc in a multi-metal aqueous solution by waste rubber tires for the design of single batch adsorber. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgariu, L.; Balan, C.; Bulgariu, D.; Macoveanu, M. Valorisation of romanian peat for the removal of some heavy metals from aqueous media. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 5891–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamwichit, A.; Dechapanya, W.; Dechapanya, W. Adsorption kinetics and isotherms of binary metal ion aqueous solution using untreated venus shell. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Cai, Q.; Mi, T.G.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, L.; Lu, Q. Interaction mechanism between lead species and activated carbon in MSW incineration flue gas: Role of different functional groups. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 436, 135252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Huan, W.W.; Teng, H.J.; Guo, J.Z.; Li, B. Effect of oxygen-containing functional group contents on sorption of lead ions by acrylate-functionalized hydrochar. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 349, 123921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Yang, S.; Mortimer, M.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Cai, P.; Huang, Q. Functional group diversity for the adsorption of lead(Pb) to bacterial cells and extracellular polymeric substances. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 295, 118651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzardo, F.H.M.; Velasco, F.G.; Correia, I.K.S.; Silva, P.M.S.; Salay, L.C. Removal of lead ions from water using a resin of mimosa tannin and carbon nanotubes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2017, 7, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Mondal, S.; Maiti, T.K. Lead (Pb2+) biosorption and bioaccumulation efficiency of Enterobacter chuandaensis DGI-2: Isotherm, kinetics and mechanistic study for bioremediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M.; Minhas, L.A.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Ali, M.A.; Mahmoud, R.M.; Saqib, S.; Nazish, M.; Zaman, W.; Mumtaz, A.S. Biosorption of Cadmium and Lead by Dry Biomass of Nostoc sp. MK-11: Kinetic and Isotherm Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavado-Meza, C.; Fernandez-Pezua, M.C.; Gamarra-Gómez, F.; Sacari-Sacari, E.; Angeles-Suazo, J.; Dávalos-Prado, J.Z. Single and Binary Removals of Pb(II) and Cd(II) with Chemically Modified Opuntia ficus indica Cladodes. Molecules 2023, 28, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitosa, A.G.; Santos, Y.T.d.C.; Menezes, J.M.C.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Teixeira, V.F.; da Silva, J.H.; Filho, F.J.d.P.; Teixeira, R.N.P.; Oliveira, T.M.B.F. Mielle Brito Ferreira Oliveira, Evaluation of Pb2+ ion adsorption by roasted and grounded barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) waste. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, A.; Škerget, M.; Čolnik, M. Removal of iron; copper, and lead from aqueous solutions with zeolite, bentonite, and steel slag. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2989–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboli, E.; Jafari, D.; Esmaeili, H. Heavy metal ions (lead, cobalt, and nickel) biosorption from aqueous solution onto activated carbon prepared from Citrus limetta leaves. Carbon. Letters 2020, 30, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, A.; Uddin, M.K.; Rao, R.A.K. Adsorptive remediation of Pb(II) from aqueous media using Schleichera oleosa bark. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position, °2θ | d-Spacing Å | Height, cts | Height, cps | Relative Intensity, % | Area, cts × °2θ | Area, cps × °2θ | Crystallite Size Only, Å | Micro Strain Only, % | FWHM Total, °2θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.10 | 3.6893 | 4.91 | 10.9 | 28.63 | 2.19 | 4.87 | 244 | 0.755 | 0.216 |

| 30.33 | 2.9439 | 1.26 | 2.79 | 7.34 | 1.2 | 2.67 | 104 | 1.409 | 0.463 |

| 33.12 | 2.7025 | 17.13 | 38.08 | 100 | 7.71 | 17.14 | 242 | 0.557 | 0.312 |

| 35.62 | 2.5184 | 16.48 | 36.63 | 96.21 | 8.13 | 18.07 | 222 | 0.566 | 0.248 |

| 40.83 | 2.20812 | 3.42 | 7.59 | 19.94 | 2.04 | 4.54 | 181 | 0.611 | 0.353 |

| 43.30 | 2.0875 | 0.92 | 2.05 | 5.37 | 0.66 | 1.46 | 134 | 0.779 | 0.690 |

| 49.47 | 1.8407 | 5.87 | 13.05 | 34.27 | 2.97 | 6.6 | 219 | 0.419 | 0.374 |

| 54.03 | 1.6957 | 7.84 | 17.43 | 45.78 | 4.05 | 9.01 | 223 | 0.379 | 0.352 |

| 57.48 | 1.6018 | 1.77 | 3.94 | 10.35 | 2.56 | 5.68 | 74 | 1.081 | 0.789 |

| 62.50 | 1.4847 | 4.64 | 10.31 | 27.09 | 3.49 | 7.75 | 155 | 0.479 | 0.495 |

| 63.93 | 1.4548 | 6.17 | 13.7 | 35.98 | 2.94 | 6.54 | 261 | 0.278 | 0.293 |

| 71.97 | 1.3109 | 1.74 | 3.88 | 10.18 | 1.17 | 2.61 | 179 | 0.366 | 0.508 |

| 74.41 | 1.2738 | 0.75 | 1.67 | 4.38 | 0.45 | 0.99 | 217 | 0.293 | 0.377 |

| 75.46 | 1.2586 | 0.77 | 1.72 | 4.51 | 0.48 | 1.07 | 180 | 0.350 | 0.606 |

| 80.65 | 1.1902 | 0.76 | 1.69 | 4.44 | 0.85 | 1.89 | 113 | 0.528 | 0.612 |

| 83.03 | 1.1621 | 0.65 | 1.44 | 3.79 | 0.54 | 1.19 | 143 | 0.406 | 0.801 |

| 84.91 | 1.1411 | 1.44 | 3.2 | 8.4 | 0.71 | 1.58 | 295 | 0.193 | 0.308 |

| 88.58 | 1.1030 | 1.41 | 3.14 | 8.24 | 0.69 | 1.53 | 311 | 0.177 | 0.245 |

| PFO | PSO | ||||||||||

| qe | K1 | R2 | qe | K2 | R2 | ||||||

| 9.4 ± 0.06 | 6.5 ± 0.07 | 0.99 | 9.5 ± 0.086 | 5.7 ± 7.6 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Langmuir | Freundlich | Temkin | |||||||||

| qm | b | R2 | Kf | n | R2 | a | b | R2 | |||

| 70.9 ± 6.6 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.99 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.96 | 0.17 ± 0.023 | 156 ± 10.6 | 0.95 | |||

| Adsorbent | q, mg/g | pH | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Honey hydrothermal biochar | 132 | 5.0 | [44] |

| Flax fibres | 10.7 | 6.0 | [42] |

| Acrylate-functionalized hydrochar | 193 | 5.0 | [49] |

| Tannin–formaldehyde resin | 13.8 | 3.5 | [51] |

| Spirulina platensis | 4.8 | 3.0 | [43] |

| Enterobacter chuandaensis DGI-2 | 98.6 | 6.5 | [52] |

| Nostoc sp. MK-11 | 83.9 | 4.0 | [53] |

| Chemically Modified Opuntia ficus indica Cladodes | 64.7 | 5.0 | [54] |

| Roasted and grounded barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) waste | 25.76 | 5.5 | [55] |

| Steel slag | 59.8 | [56] | |

| Citrus limetta leaves | 69.8 | 6 | [57] |

| Schleichera oleosa bark | 69.4 | 6 | [58] |

| Fe2O3/C composite | 70.6 | 5.0 | Present study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomaa, I.; Yushin, N.; Bayachou, M.; Stanić, V.; Zinicovscaia, I. Synthesis and Characterization of Eco-Engineered Hollow Fe2O3/Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres: Evaluating Structural, Optical, Antibacterial, and Lead Adsorption Properties. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241850

Gomaa I, Yushin N, Bayachou M, Stanić V, Zinicovscaia I. Synthesis and Characterization of Eco-Engineered Hollow Fe2O3/Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres: Evaluating Structural, Optical, Antibacterial, and Lead Adsorption Properties. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241850

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomaa, Islam, Nikita Yushin, Mekki Bayachou, Vojislav Stanić, and Inga Zinicovscaia. 2025. "Synthesis and Characterization of Eco-Engineered Hollow Fe2O3/Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres: Evaluating Structural, Optical, Antibacterial, and Lead Adsorption Properties" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241850

APA StyleGomaa, I., Yushin, N., Bayachou, M., Stanić, V., & Zinicovscaia, I. (2025). Synthesis and Characterization of Eco-Engineered Hollow Fe2O3/Carbon Nanocomposite Spheres: Evaluating Structural, Optical, Antibacterial, and Lead Adsorption Properties. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1850. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241850