Table 1 shows the weight percentages of the Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites synthesized in this study. The materials are denoted as 100-X(Al-5Cu-0.3Sc)-(X)B

4C (X = 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20), where X = 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 are weight percentages and are labeled as 0B

4C, 5B

4C, 10B

4C, 15B

4C, and 20B

4C, respectively. The Al-5Cu-0.3Sc matrix obtained by the melt-spinning process exhibited an ultra-fine, nanocrystalline structure due to rapid solidification at a cooling rate of 10

5 to 10

8 K/s, while the added B

4C reinforcement was in the micron size range. Therefore, the obtained materials can be defined as nanostructured aluminum-based composites reinforced with micro-sized ceramic B

4C particles in a nanocrystalline metallic matrix. This hybrid structural configuration is expected to combine the high strength and stability of the nanocrystalline Al-Cu-Sc matrix with the internal hardness and wear resistance provided by B

4C. The systematic variation in B

4C content enables a comprehensive assessment of its effects on density, hardness, wear rate, and corrosion resistance, providing valuable insights for optimizing nanostructured aluminum composites for advanced engineering applications.

3.1. XRD Analysis

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites with varying B

4C contents (0–20 wt.%). The diffraction peaks observed at approximately 2θ = 38.4°, 44.7°, 65.1°, 78.2°, and 82.4 correspond to the (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes of the face-centered cubic (FCC) Al phase (PDF#04-0778) (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) planes and confirm that the aluminum matrix retains its crystalline structure after processing. In addition to the main Al reflections, weak peaks corresponding to the Al

2Cu (PDF#26-0015) and Al

3Sc (PDF#65-0423) phases were detected, indicating the precipitation of these secondary strengthening compounds within the matrix. The formation of Al

2Cu indicates Cu segregation and precipitation during solid-state processing, while Al

3Sc confirms the stability of Sc-rich precipitates that contribute to grain refinement and thermal stability [

8]. With the addition of B

4C, several low-intensity peaks at 2θ = 27.1°, 37.9°, and 41.6° were observed, corresponding to the B

4C phase (PDF# 23-0073), confirming the successful incorporation of the ceramic reinforcement. No peaks associated with oxide or impurity phases were detected, indicating that the powder metallurgy and sintering processes were carried out under well-controlled atmospheric conditions. Furthermore, no diffraction peaks corresponding to Al

3BC or any other Al-B

4C reaction product were observed, confirming that the sintering temperature (625 °C) was insufficient to trigger interfacial reactions between Al and B

4C. Thus, the B

4C particles remained chemically stable and contributed primarily through mechanical reinforcement rather than interfacial phase formation.

As the B4C content increased, the intensity of the Al peaks decreased slightly, and the diffraction lines broadened moderately. This behavior indicates grain refinement and increased lattice stress resulting from the inclusion of hard ceramic particles and the mismatch in thermal expansion coefficients between the Al matrix and B4C. The presence of the Al3Sc phase is particularly important because, even at low concentrations, it contributes to grain boundary stabilization and enhances microstructural stability by forming consistent L12-structured precipitates. Overall, the coexistence of Al, Al2Cu, Al3Sc, and B4C phases demonstrates a dual-strengthening mechanism that operates synergistically: precipitation hardening (via Al2Cu and Al3Sc) and dispersion hardening (via B4C particles). This phase configuration is consistent with microstructural observations and subsequent improvements in hardness and wear resistance.

The crystallite size (⟨D⟩) and lattice microstrain (⟨ε⟩) of the Al matrix were quantified using the Scherrer equation and peak-broadening analysis. For each composition, the dominant Al reflections ((111), (200), (220), (311), and (222)) were selected, and the corresponding 2θ positions and full width at half maximum (FWHM) values were used to calculate the crystallite size and strain. The Scherrer equation was used as follows [

35]:

where

K = 0.94 is the shape factor,

λ = 0.15406 nm (Cu Kα radiation),

β is the measured FWHM (in radians), and

θ is the Bragg angle.

The lattice microstrain (

ε) was calculated from peak broadening using

The crystallite size and microstrain values obtained from individual peaks were averaged for each composition, and the resulting ⟨D⟩ and ⟨ε⟩ values are presented in

Table 2. The results indicate that the Al matrix remains nanocrystalline across all compositions (⟨D⟩ ≈ 24–36 nm). Increasing B

4C content generally decreases crystallite size, while the microstrain increases (from 2.11 × 10

−3 to 3.34 × 10

−3), confirming enhanced lattice distortion and defect accumulation at Al/B

4C interfaces. It should also be noted that the slight anomaly in ⟨D⟩ at 15 wt.% B

4C does not persist at 20 wt.%. This can be understood in terms of the competing effects of particle-induced fracturing and milling-induced heterogeneity. At 15 wt.% B

4C, the reinforcement content is high enough to generate pronounced local stress fields and partial agglomeration, which promote heterogeneous deformation and may allow limited local recovery, leading to slightly coarser crystallites in some regions. At 20 wt.% B

4C, however, the much higher fraction of hard particles intensifies repeated fracturing during mechanical alloying to such an extent that recovery is largely suppressed and a finer, more uniformly refined nanocrystalline matrix is obtained, even though the overall porosity remains relatively high. This competition between local heterogeneity and severe particle-assisted fragmentation provides a consistent explanation for the observed trend in ⟨D⟩.

3.2. Microstructural Characterization (SEM and EDX)

SEM micrographs of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites at two magnification levels (100 µm and 50 µm), together with the corresponding EDS spot analyses, confirm the elemental composition of the identified phases (Al matrix, Al

2Cu intermetallic, and B

4C reinforcement). Although the nanoscale Al

3Sc phase detected by XRD is not readily distinguishable in the SEM images due to its ultrafine dispersion, its presence is confirmed by the diffraction results shown in

Figure 4 [

8]. The unmodified sample (0B

4C) exhibits a relatively disordered morphology with visible interparticle voids and loosely bonded regions between melted and curved particles. These voids indicate incomplete densification during sintering and limited plastic flow of the rapidly solidifying aluminum matrix. With the addition of B

4C, the morphology becomes significantly more homogeneous, and the interparticle voids are markedly reduced. The dark, angular regions clearly observed in B

4C-containing specimens correspond to well-dispersed ceramic reinforcement particles throughout the matrix and along grain boundaries. Their presence enhances interfacial bonding and limits grain coarsening, resulting in a denser, more stable microstructure. This observation is in good agreement with the improved relative density and hardness values reported in

Table 3 and

Figure 5.

In contrast, the brighter gray areas in the SEM images may represent Cu-rich intermetallic compounds (such as Al2Cu- or Al-Cu-Sc-type phases) formed during solidification and sintering. Given the low scandium content (0.3% by weight), Sc atoms are predominantly dissolved in the aluminum matrix. They are found as nano-scale Al3Sc precipitates rather than visible secondary phases at the given magnifications. Although these precipitates are not directly soluble, they contribute to grain refinement and microstructural stability. Overall, SEM observations confirm that B4C reinforcement effectively increases densification and microstructural homogeneity. Meanwhile, the rapid solidification induced by melt spinning helps preserve a fine-grained, defect-minimized matrix, providing an ideal foundation for the subsequent strengthening and corrosion performance of the composites.

3.3. Density and Microhardness Measurements

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between relative density and Vickers microhardness for Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites, with the corresponding results summarized in

Table 3. Experimental measurements revealed that the relative density remained within a narrow range of 85.9–88.1%, whereas the microhardness increased continuously and significantly with increasing B

4C content. Although the relative density values (85.9–88.1%) appear to fall within a narrow range, the incorporation of 5–20 wt.% B

4C inherently promotes interfacial porosity due to the limited wettability between Al and the rigid ceramic particles. During pressing and sintering, the restricted flow of the Al matrix around angular B

4C particles and the reduced interfacial diffusion capacity result in localized pore retention, particularly in B

4C-rich regions. Minor gas entrapment originating from high-energy powder milling may further contribute to this effect. While these pores are small enough not to dominate the mechanical response, they provide a consistent explanation for the slight reduction in density at higher B

4C contents and must also be considered when evaluating corrosion behavior, given the potential formation of microgalvanic sites [

36,

37]. The base alloy (0B

4C) exhibited a microhardness of 44.9 HV, while this value gradually increased to 101.2 HV, 107.3 HV, 134.4 HV, and 188.2 HV for the 5B

4C, 10B

4C, 15B

4C, and 20B

4C nanocomposites, respectively. This corresponds to an overall hardness improvement of approximately 319% from 0 wt.% to 20 wt.% B

4C.

Several complementary mechanisms govern the progressive increase in hardness with rising B4C content. First, B4C particles act as load-bearing reinforcements, restricting plastic deformation by transferring a portion of the applied stress to the ceramic phase. Their presence also induces strain incompatibility at the particle–matrix interfaces, increasing the density of geometrically necessary dislocations. Second, the rapid solidification process produces a refined Al matrix and promotes the formation of fine Al2Cu precipitates. The nanoscale Al3Sc dispersoids retained from melt spinning further stabilize this refined structure during mechanical milling and sintering, thereby limiting grain coarsening. The synergy of these mechanisms results in the observed steady strengthening trend.

At higher B4C levels, particularly at 20 wt.%, the sharp increase in hardness can be attributed to the dense distribution of hard ceramic particles, which significantly impede dislocation motion through the Orowan bypass mechanism in addition to particle–matrix load transfer. Although a slight reduction in relative density occurs at B4C contents above 10 wt.%, the reinforcement effects clearly outweigh the influence of porosity. The marginal density reduction is related to the limited wettability of B4C in aluminum and occasional particle agglomeration, which can locally restrict matrix flow during compaction and sintering.

The microhardness increased from 44.9 HV (0B4C) to 188.2 HV (20B4C), corresponding to an approximately 319% (4.19-fold) increase. This substantial enhancement reflects the combined contributions of load-bearing reinforcement, increased geometrically necessary dislocations, precipitation strengthening from Al2Cu, and the microstructural stabilization provided by nanoscale Al3Sc dispersoids. Although a slight reduction in density is observed at higher B4C contents, the strengthening imparted by the hard ceramic phase clearly outweighs the detrimental effects of porosity.

3.4. Wear Behavior

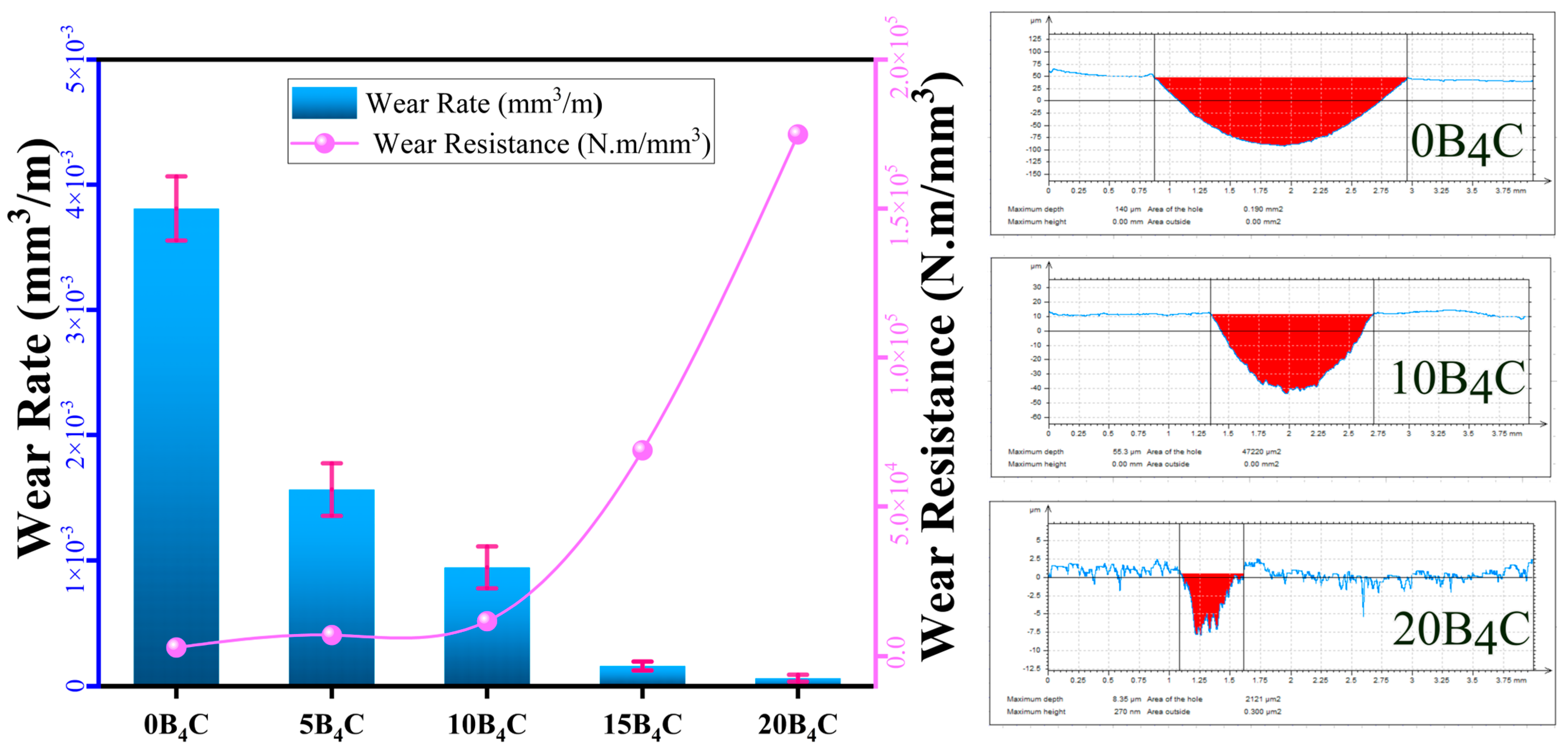

Figure 6 shows the change in wear rate and wear resistance of the Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites as a function of B

4C content. As the amount of B

4C increases, the profilometer cross-sectional wear tracks clearly become narrower and shallower, indicating a substantial reduction in material loss. The wear rate decreased steadily from 3.81 × 10

−3 mm

3/m for the unmodified alloy (0B

4C) to 6.29 × 10

−5 mm

3/m for the nanocomposite containing 20% B

4C by weight. Conversely, wear resistance increased sharply from 2.89 × 10

−3 mm

3/m to 1.75 × 10

−5 mm

3/m over the same composition range. This strong inverse relationship clearly demonstrates the dominant strengthening and tribological improvement provided by B

4C reinforcement. The marked decrease in wear rate with increasing reinforcement content can be attributed to the hard and chemically stable structure of B

4C particles, which act as load-bearing components during sliding contact. These particles minimize the direct interaction area between the counter surface and the Al matrix, suppressing adhesive wear and plastic deformation. In parallel, the increased microhardness of the nanocomposites (

Figure 5) enhances resistance to friction cutting and surface material loss. The sharp drop in wear rate above 10% by weight of B

4C indicates a transition dominated by particle–matrix load transfer and interfacial bonding, forming a robust barrier against material loss.

At low B4C content (≤5% by weight), the wear mechanism is primarily adhesive and abrasive, driven by partial exposure of the soft Al-Cu matrix and limited reinforcement coverage of the wear surface. At higher reinforcement levels (10–15 wt.%), the wear mechanism transitions to a mixed mode characterized by micro-shearing and shallow abrasive grooves. The 20B4C nanocomposite exhibits the lowest wear rate and highest wear resistance, indicating a predominantly light abrasive mechanism with limited plastic flow. The improvement in tribological performance at this stage stems from the combined effects of dispersion strengthening, grain refinement, and the formation of a mechanically stable tribo-layer. The results generally confirm that increasing the B4C content significantly enhances the wear resistance of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc nanocomposites. The 15–20% B4C weight range provides an optimal balance between hardness and compactness, effectively minimizing material loss during sliding. These findings are consistent with the hardness trend and confirm that wear resistance is primarily determined by the degree of dispersion strengthening and the microstructural stability of the composite surface.

As a result, the progressive decrease in wear rate from 3.81 × 10−3 mm3/m to 6.29 × 10−5 mm3/m and the corresponding ~60-fold increase in wear resistance demonstrate that B4C reinforcement significantly improves the tribological behavior of the Al-5Cu-0.3Sc matrix. This improvement is primarily governed by the load-bearing effect of B4C particles, reduced plastic deformation, and the transition from severe adhesive wear to predominantly abrasive and mild oxidative wear as the reinforcement content increases.

Figure 7 shows SEM micrographs of the worn surfaces of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites tested at 10 N, revealing that the wear mechanisms evolved progressively with increasing B

4C content. The surfaces exhibit distinct morphological features, including adhered layers, delamination regions, oxide films, and embedded reinforcement particles, each of which correlates with the mechanical and tribological properties shown in

Figure 7. The unreinforced alloy (0B

4C,

Figure 7a) exhibits pronounced plastic deformation and extensive contamination layers, typical features of surface adhesive wear. As a result of repeated adhesion–fracture cycles between the soft Al-Cu matrix and the steel counterball, large delamination areas and accumulated wear debris are evident. During sliding, local temperature increases promote oxidative wear, leading to the formation of continuously fracturing and reforming thin Al

2O

3-based tribofilms. The combined effects of plastic flow and oxide fatigue result in a rough morphology characterized by adhesive oxidative delamination.

At a 5% B

4C weight ratio (

Figure 7b), delamination becomes more localized, and shallow grooves begin to appear, indicating a transition to a mixed adhesive–abrasive wear mode. Dispersed B

4C particles function as load-carrying regions, reducing plastic deformation and limiting severe adhesion. However, partial particle agglomeration and subsurface stress concentration can still initiate fatigue cracks, which propagate to the surface, forming small delamination flakes and oxidized residue clusters. At higher reinforcement levels (10–20% B

4C by weight;

Figure 7c–e), the worn surfaces become significantly smoother, with fewer delamination regions. On the surface, fine micro-scratch grooves dominate, along with isolated embedded B

4C particles and a thin mechanically mixed layer (MML). This layer forms through the mechanical entrapment of oxidized residues and hard particles, acting as a self-lubricating tribofilm that reduces direct metal-to-metal contact. As a result, the primary wear mechanism shifts toward abrasive wear, becoming consistent with significant improvements in hardness and wear resistance (

Figure 5). Overall, the wear mechanism evolves from adhesive–oxidative delamination in the unmodified alloy to abrasive wear in highly reinforced nanocomposites. The inclusion of B

4C not only increases hardness and load-carrying capacity but also stabilizes the oxide layer, reducing fatigue-induced delamination.

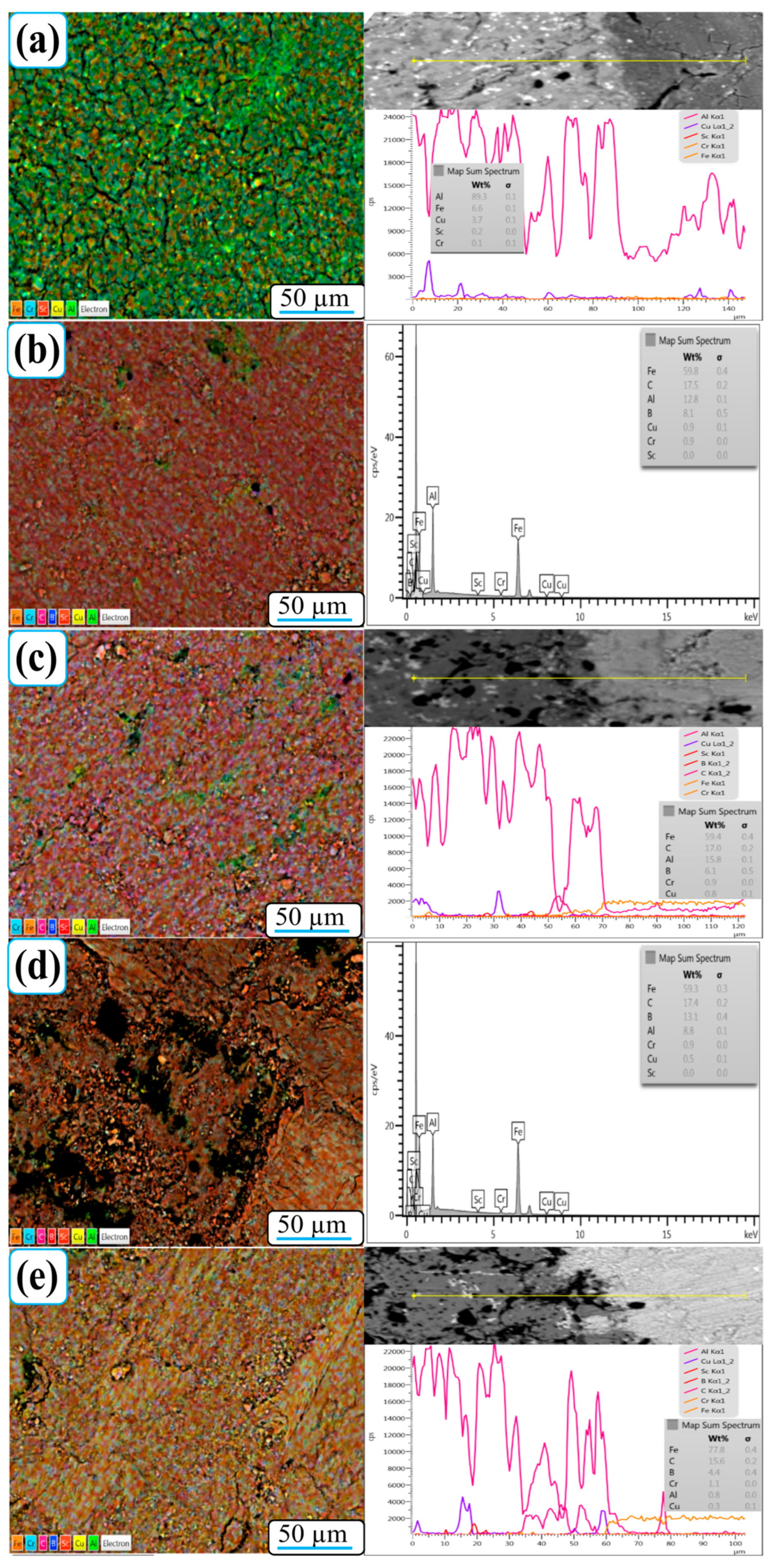

Figure 8 shows SEM-EDX element mapping images of the worn surfaces of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites with varying B

4C contents (0–20 wt.%). The element maps reveal a homogeneous distribution of Al, Cu, Sc, B, and C across all samples, confirming that the processing route used effectively promoted the uniform dispersion of reinforcement particles within the aluminum matrix. Minor fluctuations observed in the B and C signals are attributed to EDX’s inherent limitations in detecting low-atomic-number (light) elements, rather than to actual compositional inhomogeneity [

38]. This ensures that the detected distribution trends reliably represent the true spatial distribution of B

4C within the nanocomposites.

For the 0B

4C nanocomposite (

Figure 8a), the worn surface predominantly contains Al, Cu, and O, indicating the formation of a thin oxide film during sliding. The local enrichment of Fe and Cr is minimal, indicating limited material transfer from the steel counterball. As the B

4C content increases (

Figure 8b–e), the surface distribution of Fe, Cr, and C becomes more pronounced. This trend implies intensified friction interaction with the counter surface, leading to microfractures in the steel ball and subsequent transfer of Fe- and Cr-rich residues to the composite surface. These transferred elements tend to accumulate around B

4C-rich regions, facilitating oxidation and mechanical embedding within the localized heating wear trace.

The presence of Fe- and Cr-enriched oxide islands, along with oxygen-rich regions, supports the formation of a protective tribo-oxide layer that minimizes metal-to-metal contact and reduces adhesive wear. Particularly in 15B

4C and 20B

4C nanocomposites, higher reinforcement content promotes the development of a more stable mechanical mixing layer (MML) composed of Al, B, C, Fe, and O. This compact oxide–ceramic film acts as a self-lubricating barrier, consistent with the significant reduction in wear rate and increased wear resistance reported in

Figure 6. Therefore, EDX mapping results clearly show that the inclusion of B

4C not only increases element homogeneity within the nanocomposite but also promotes the formation of a composite tribofilm consisting of oxide, metallic, and ceramic phases. This tribo layer plays a dominant role in wear protection by stabilizing surface reactions, evenly distributing stress, and preventing severe delamination during sliding.

In addition to the area maps, EDS line-scan profiles were obtained for the 0B4C, 10B4C, and 20B4C specimens, traversing from the unworn surface into the wear track. These profiles clearly demonstrate the compositional transition caused by sliding. The unworn region exhibits strong Al and Cu signals, whereas the worn area shows significant enrichment of Fe and Cr due to counterbody transfer. B and C intensities also increase locally within the wear track as fragmented B4C particles become exposed and incorporated into the mechanically mixed layer. This direct comparison between unworn and worn regions confirms the tribo-chemical evolution captured in the mapping results.

3.5. Corrosion Behavior

Figure 9a shows the potentiodynamic polarization curves of Al-5Cu-0.3Sc-B

4C nanocomposites, while the relevant electrochemical parameters are summarized in

Figure 9b and

Table 4. The corrosion potential (

Ecorr) and corrosion current density (

Icorr) clearly demonstrate the effect of B

4C content on the corrosion behavior of the nanocomposites. The base alloy (0B

4C) exhibited the most noble corrosion potential (−525 mV) and the lowest current density (9.68 µA cm

−2), corresponding to a corrosion rate of 0.117 mm/year. However, with increasing B

4C content, both

Icorr and the corrosion rate gradually increased, reaching 481.6 µA cm

−2 and 6.14 mm/year, respectively, for the 20B

4C nanocomposite.

This trend suggests that while adding B

4C enhances hardness and wear resistance, it reduces corrosion performance. The presence of B

4C creates additional interfaces between the ceramic reinforcement and the metallic matrix. These interfaces, which have different electrochemical potentials, function as microgalvanic cells when exposed to chloride-containing electrolytes, thereby accelerating the anodic dissolution of the aluminum matrix. Increased porosity at higher B

4C loadings (

Table 3) further facilitates electrolyte ingress, promoting localized corrosion along particle–matrix boundaries.

Polarization curves reveal that all nanocomposites exhibit active corrosion behavior, characterized by the absence of a significant passivation region, unlike aluminum alloys in chloride environments. The similar slopes of the cathodic branches in all samples indicate that oxygen reduction remains the dominant cathodic process. In contrast, the anodic response is strongly influenced by microgalvanic coupling associated with B

4C interfaces [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The shift of

Ecorr toward more negative values and the significant increase in

Icorr at a B

4C weight ratio above 10% confirm that particle agglomeration and interfacial defects formed during sintering disrupt the continuity of the protective oxide film. Despite the observed decrease in corrosion resistance, nanocomposites maintain acceptable electrochemical stability for structural applications where mechanical and wear performance are prioritized. The overall results emphasize a balance between tribological improvement and corrosion resistance, highlighting the importance of optimizing B

4C distribution during processing and minimizing interfacial porosity to achieve balanced performance [

32,

43].

As a result, the corrosion rate increased from 0.117 mm/year (0B4C) to 6.136 mm/year (20B4C), corresponding to an approximately 52-fold increase. This strong deterioration in corrosion resistance is attributed to microgalvanic coupling between B4C particles, the Al matrix, and Al2Cu intermetallics. The presence of ceramic particles locally disrupts the passive film and increases galvanic interfaces, while the Al2Cu phase acts as a cathodic site, accelerating localized dissolution. The combined effect of passive film discontinuity and galvanic interactions results in progressively higher corrosion rates as B4C content increases.

In addition to microgalvanic coupling, the corrosion response is strongly influenced by the intrinsic porosity of the PM-processed composites. The 85.9–88.1% relative density promotes electrolyte penetration and local discontinuities in the oxide film, which accelerate pit initiation. Although B4C is only weakly conductive, literature indicates that it behaves as a slightly cathodic phase relative to Al, enhancing matrix dissolution at the particle–matrix interface. This mild cathodic shift is sufficient to drive localized anodic dissolution of the surrounding Al when exposed to chloride electrolytes, causing B4C-rich regions to act as microgalvanic initiation sites. The effect becomes more pronounced when porosity or interfacial defects facilitate electrolyte access to the Al/B4C interface. The absence of Al3BC or related phases in XRD confirms that the chosen sintering temperature avoided interfacial reaction products that could further alter electrochemical behavior. Therefore, the overall corrosion tendency arises from the synergistic effects of porosity-driven oxide disruption and mild B4C-induced microgalvanic coupling.

The deeper analysis of hardness, wear behavior, and corrosion response confirms that the combined effects of reinforcement-induced microstructural refinement, load-bearing strengthening, and microgalvanic interactions govern the performance evolution of the Al-Cu-Sc-B4C system.

3.6. Synergistic Strengthening Mechanism of Sc and B4C

The mechanical performance of the Al-Cu-Sc-B4C nanocomposites arises from the cooperative interaction between Al3Sc nanoprecipitates and B4C ceramic particles, which contribute through distinct yet complementary strengthening pathways. During rapid solidification, the formation of fine and thermally stable Al3Sc dispersoids provides effective Zener pinning, suppressing grain boundary migration and preserving a refined matrix capable of sustaining high dislocation densities. This refined structure enhances the alloy’s intrinsic ability to accommodate subsequent reinforcement introduced during mechanical milling. Simultaneously, B4C particles generate strong strain gradients at the particle–matrix interfaces, leading to the formation of a high density of geometrically necessary dislocations. These dislocations not only impede plastic flow directly through Orowan looping but also promote the nucleation of secondary Al2Cu and Al3Sc precipitates, further intensifying precipitation-based strengthening. At higher B4C fractions, the interaction becomes increasingly synergistic: the matrix stability ensured by Al3Sc enables effective load transfer, while B4C-induced dislocation accumulation enhances the precipitation response. This dual mechanism explains both the substantial hardness increment (from 44.9 HV to 188.2 HV; +319%) and the >98% reduction in wear rate observed in the developed composites. Collectively, the integration of thermally stable Al3Sc dispersoids with rigid B4C reinforcements establishes a multiscale strengthening network—grain refinement, precipitation strengthening, load transfer, and dislocation hardening—which governs the superior mechanical and tribological behavior of the alloy system.

Beyond mechanical enhancement, this synergy enables the material to meet the functional requirements of advanced lightweight engineering applications. The achieved hardness, high wear resistance, stable tribofilm formation, and improved surface durability make these nanocomposites suitable for components subjected to repeated frictional loading, such as automotive piston skirts, cylinder liners, sliding bearings, and other tribologically loaded machine elements. Furthermore, the combined thermal stability of Al3Sc and the high softening resistance of B4C indicate potential for service in moderately elevated-temperature environments. While additional optimization, such as tailored heat treatment or B4C surface modification, could further expand the performance window, the present results demonstrate that the Al-Cu-Sc-B4C system offers a competitive balance of low density, high strength, and wear resistance suitable for next-generation structural and tribological applications.