Porous Silicon and Silicon Nanowires for On-Chip Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

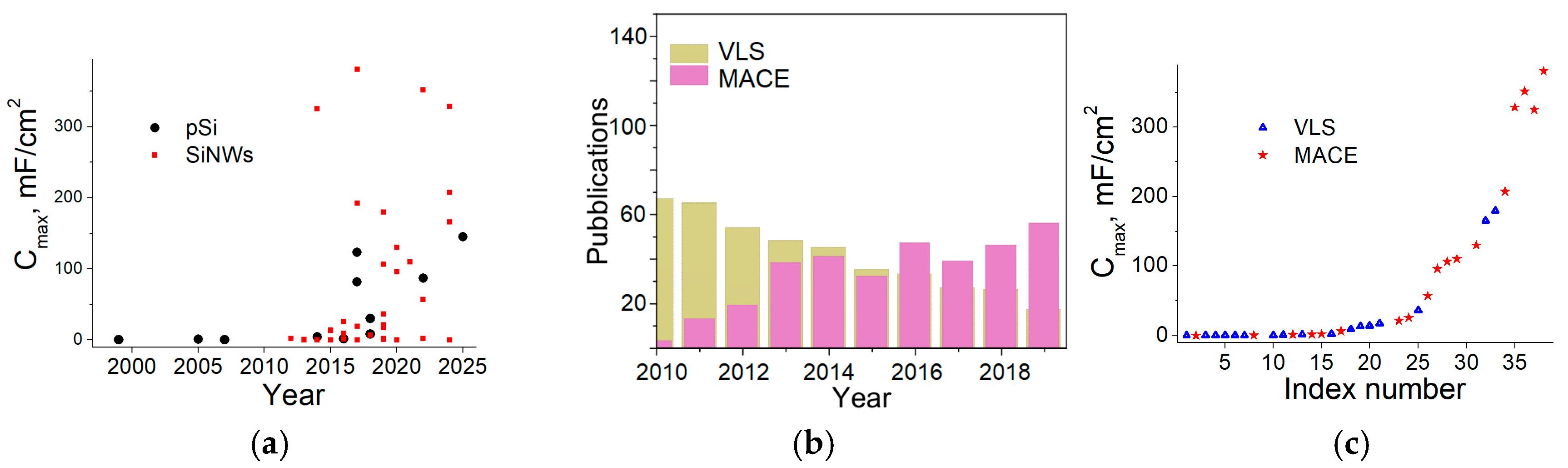

2. pSi/SiNW Formation

2.1. AE

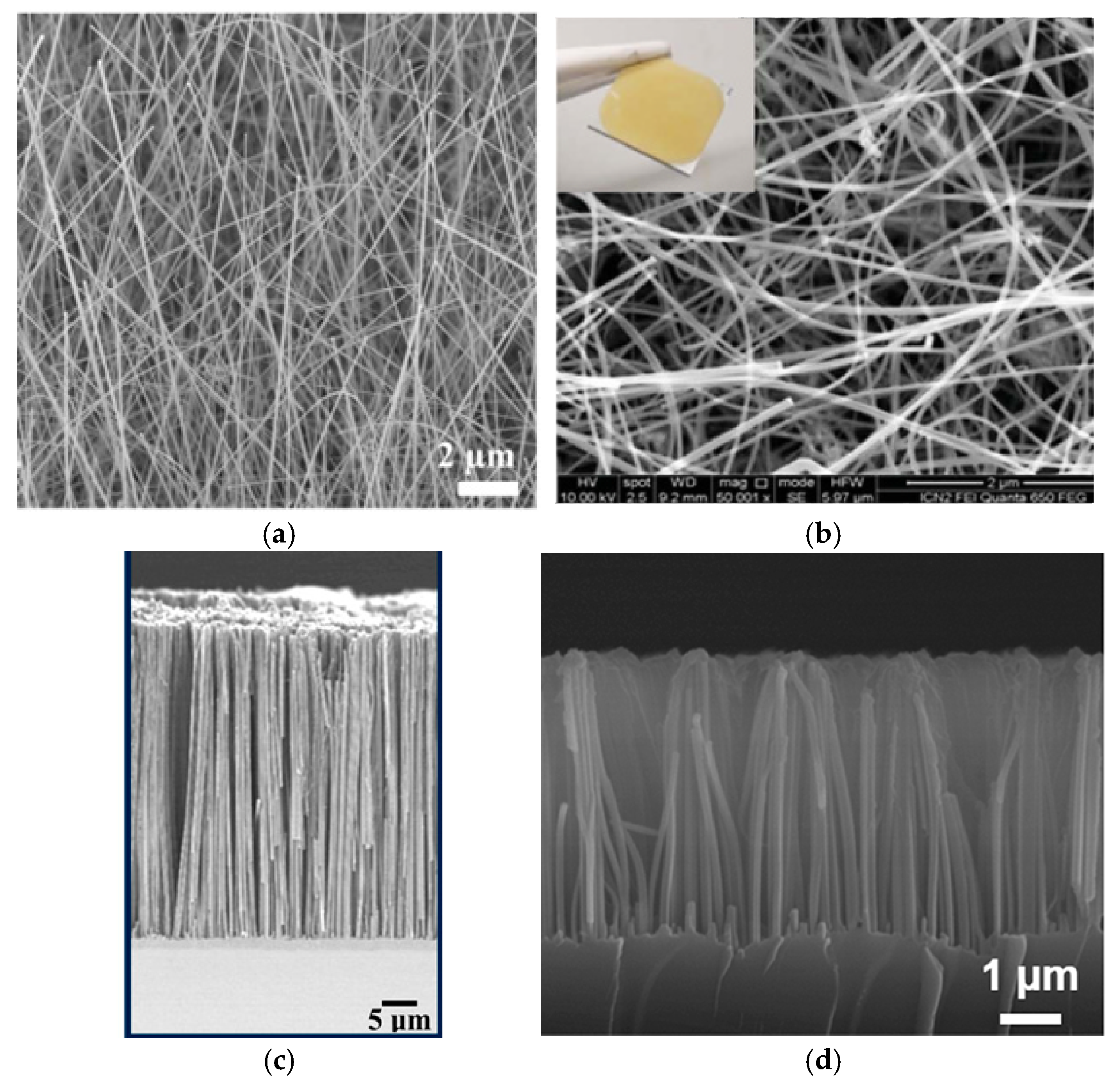

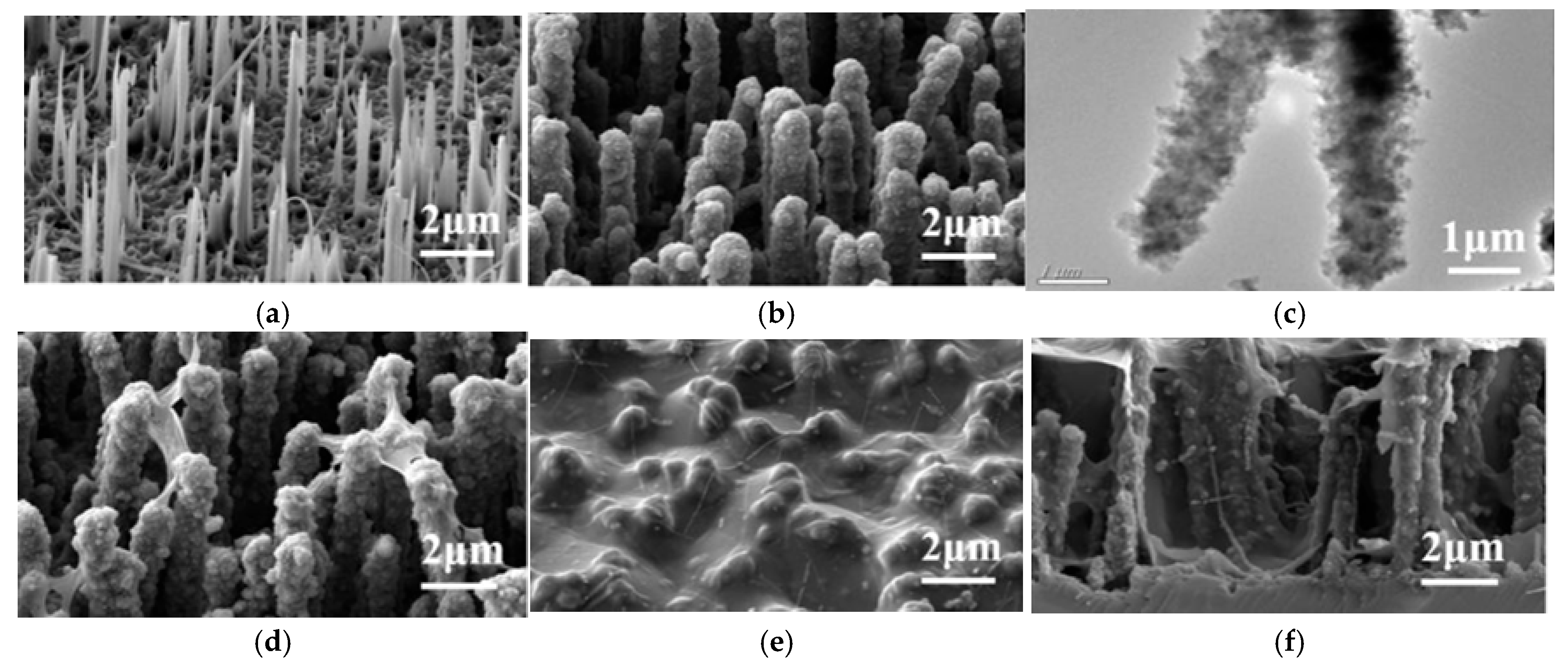

- •

- The Beale model—electric field lines concentrate at surface irregularities, focus current flow at the pore tips, and locally enhance dissolution there.

- •

- Diffusion-limited model—during pore generation, a hole diffuses to the silicon surface and reacts with a Si surface atom. The pore tips are the most likely contact site for particle diffusion.

- •

- Quantum model—the increase in the pSi band gap significantly reduces the concentration of mobile charge carriers up to “depletion”. The current is then limited to the pore tips by increasing the electric field, and the porous structure is passivated by the quantum effect.

2.2. DRIE

2.3. MACE

- (1)

- Higher aspect ratio: thicker metal, longer time, increased stirring, higher doping level, and larger etchant concentration;

- (2)

- Larger diameter: thicker metal, higher temperature, increased stirring, and lower doping level;

- (3)

- Higher length: longer time;

- (4)

- Higher etching rate: higher temperature.

2.4. VLS

2.5. Comparison

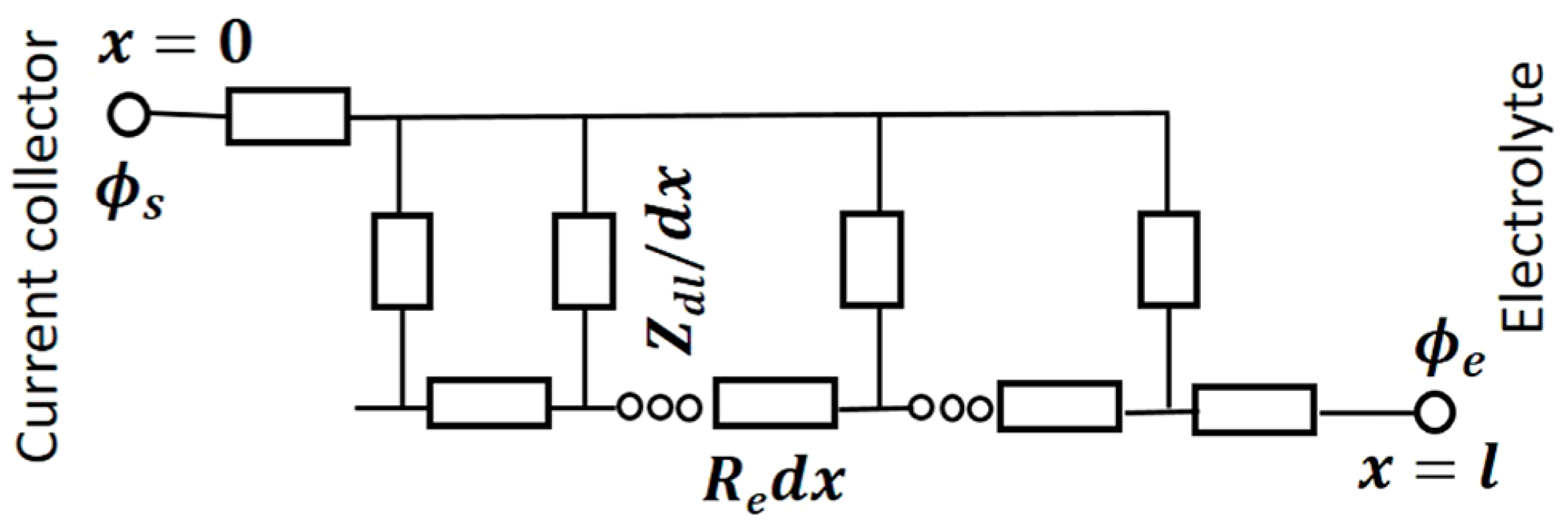

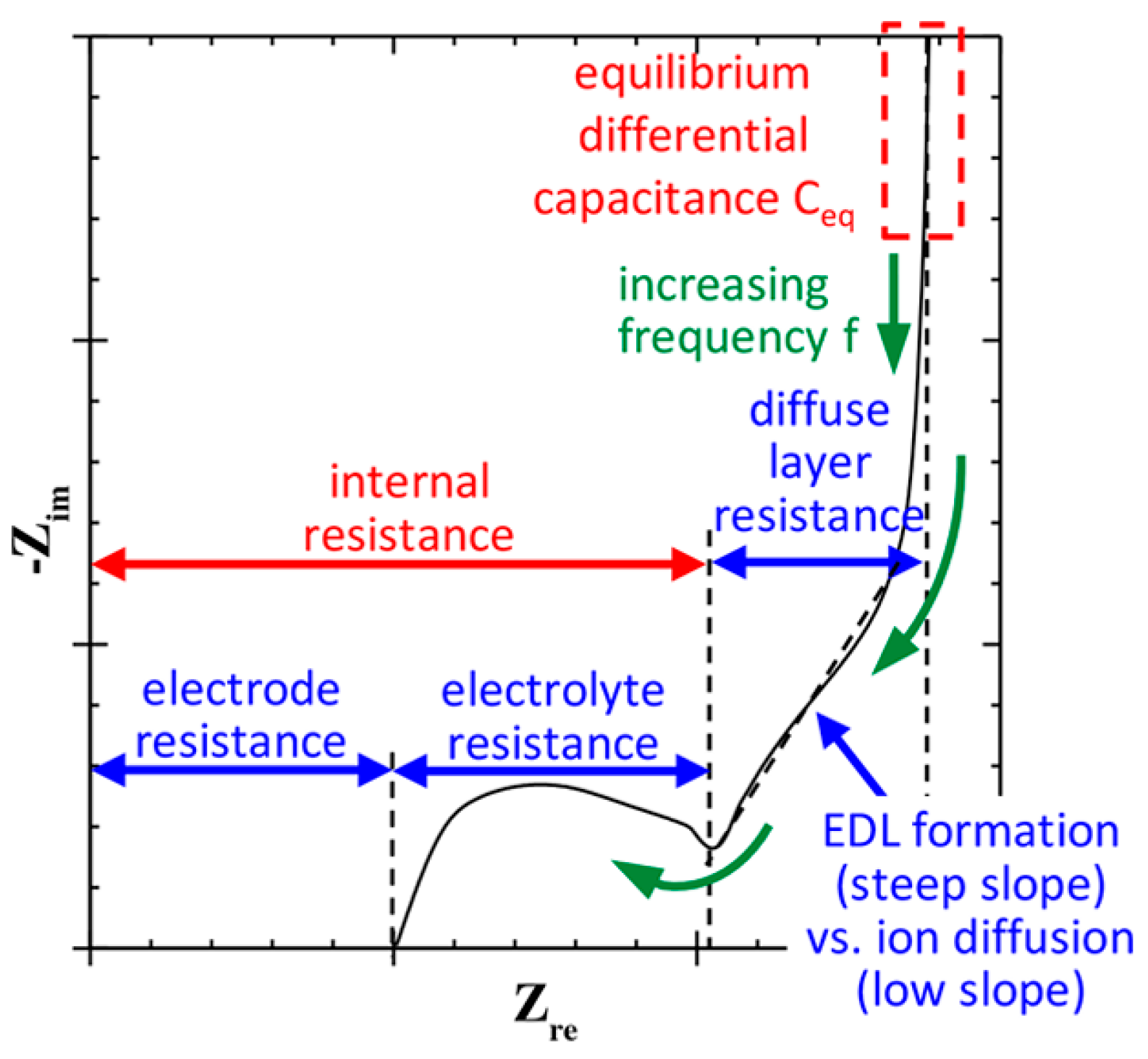

3. Electrochemical Performance

- (1)

- An electrical double layer (EDL) is formed due to electrostatic attraction between the charged electrode surface and the counter ions of the electrolyte. EDL-materials exhibit a close-to-rectangular shape of cyclic voltammograms (CVA) and a linear galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) curve;

- (2)

- Pseudocapacitance arises from surface redox reactions, which can cause deviation of the CVA form from a rectangular shape or even the appearance of peaks on the CVA.

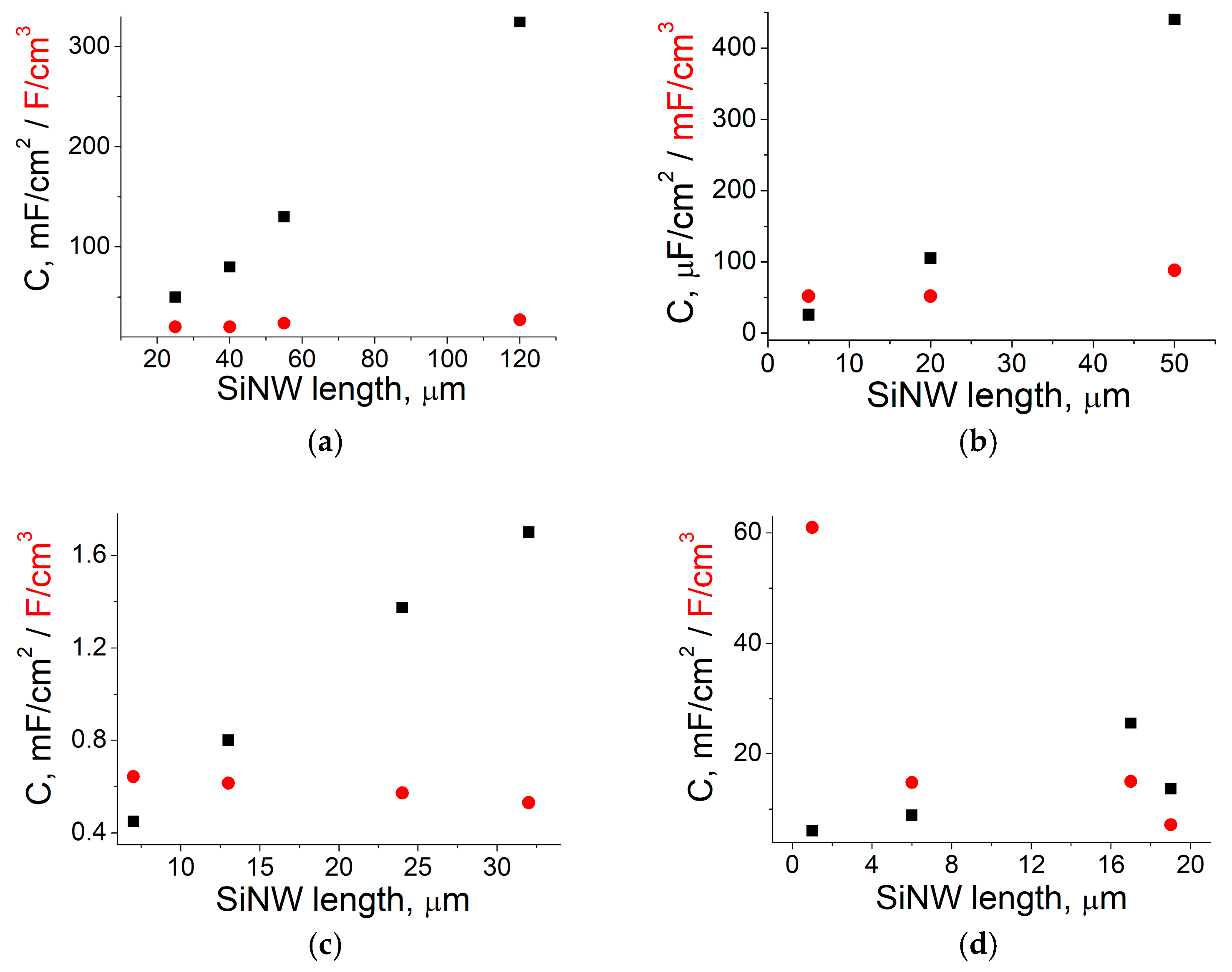

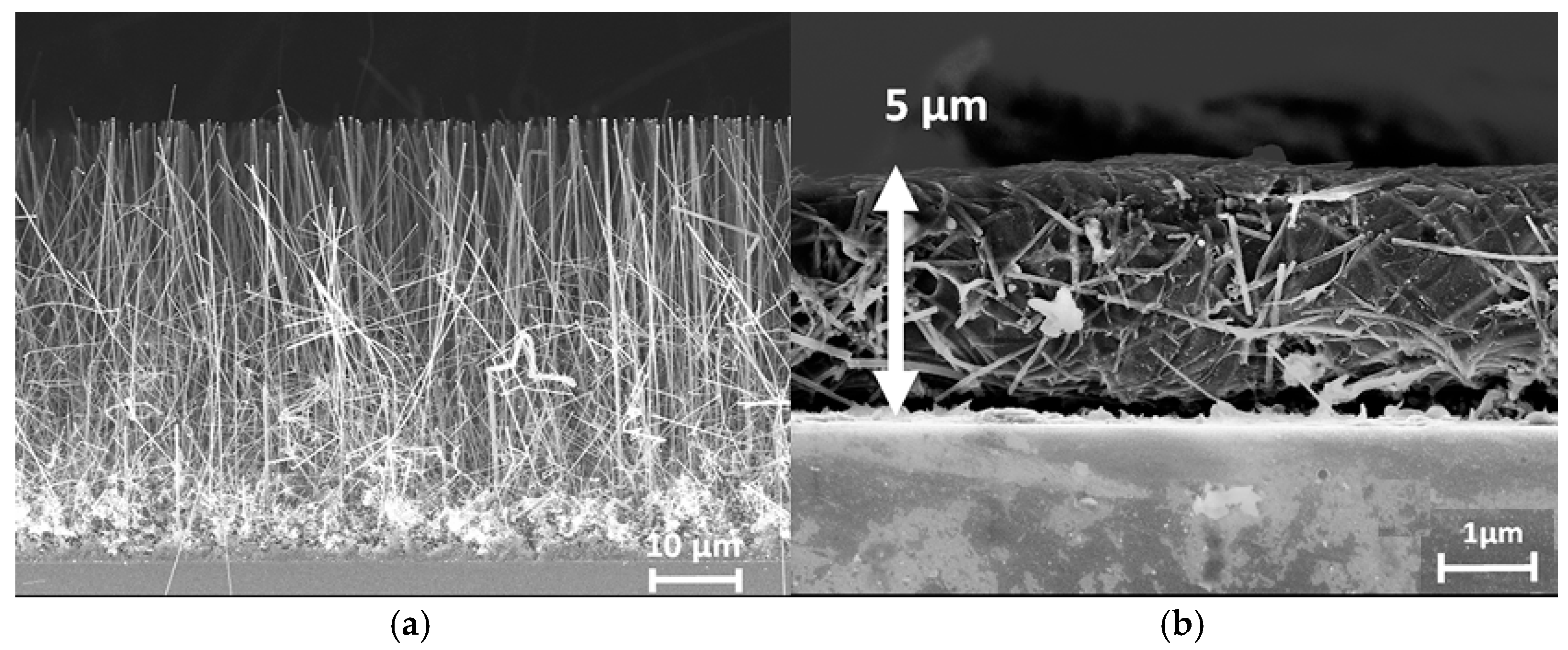

4. SiNW Length and PSi Depth

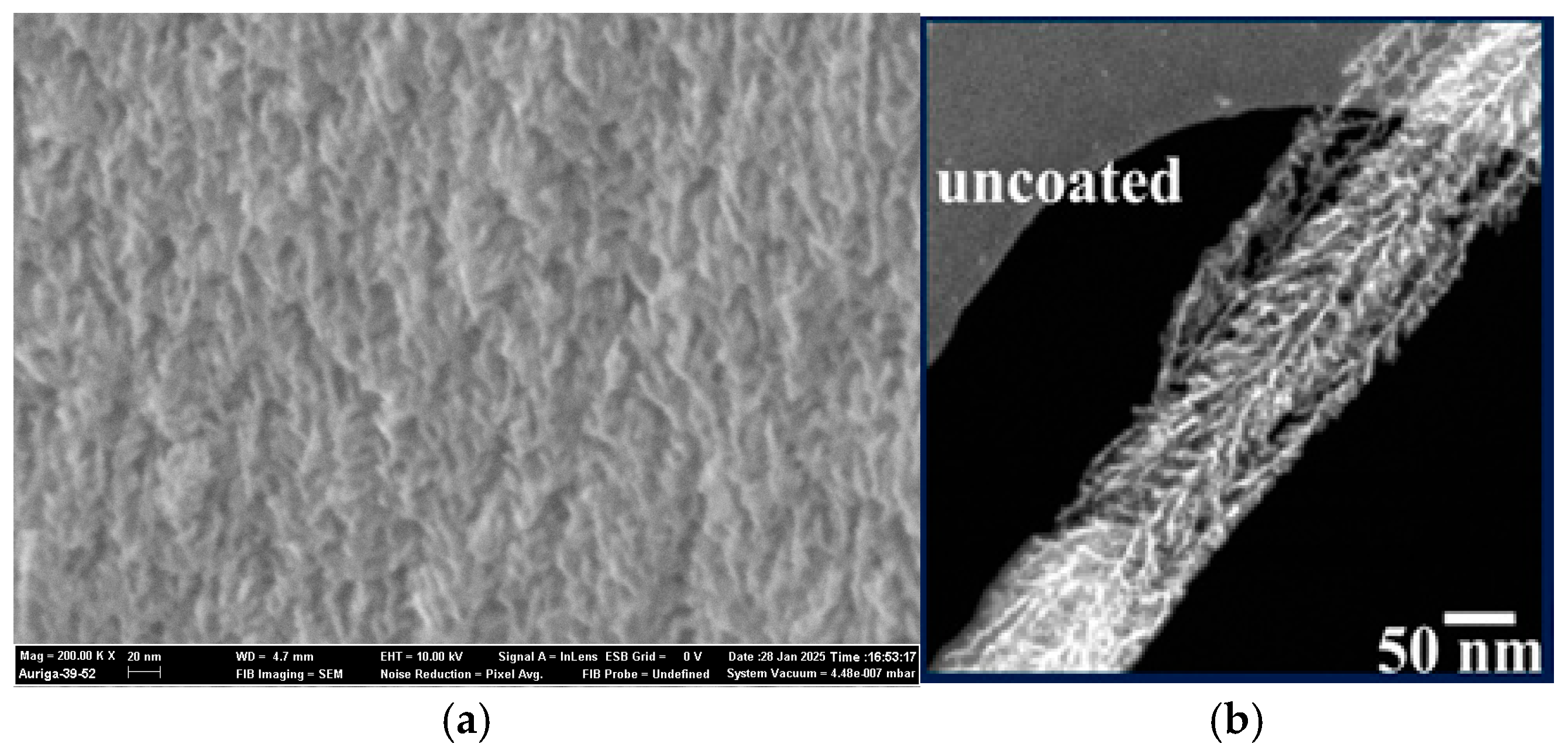

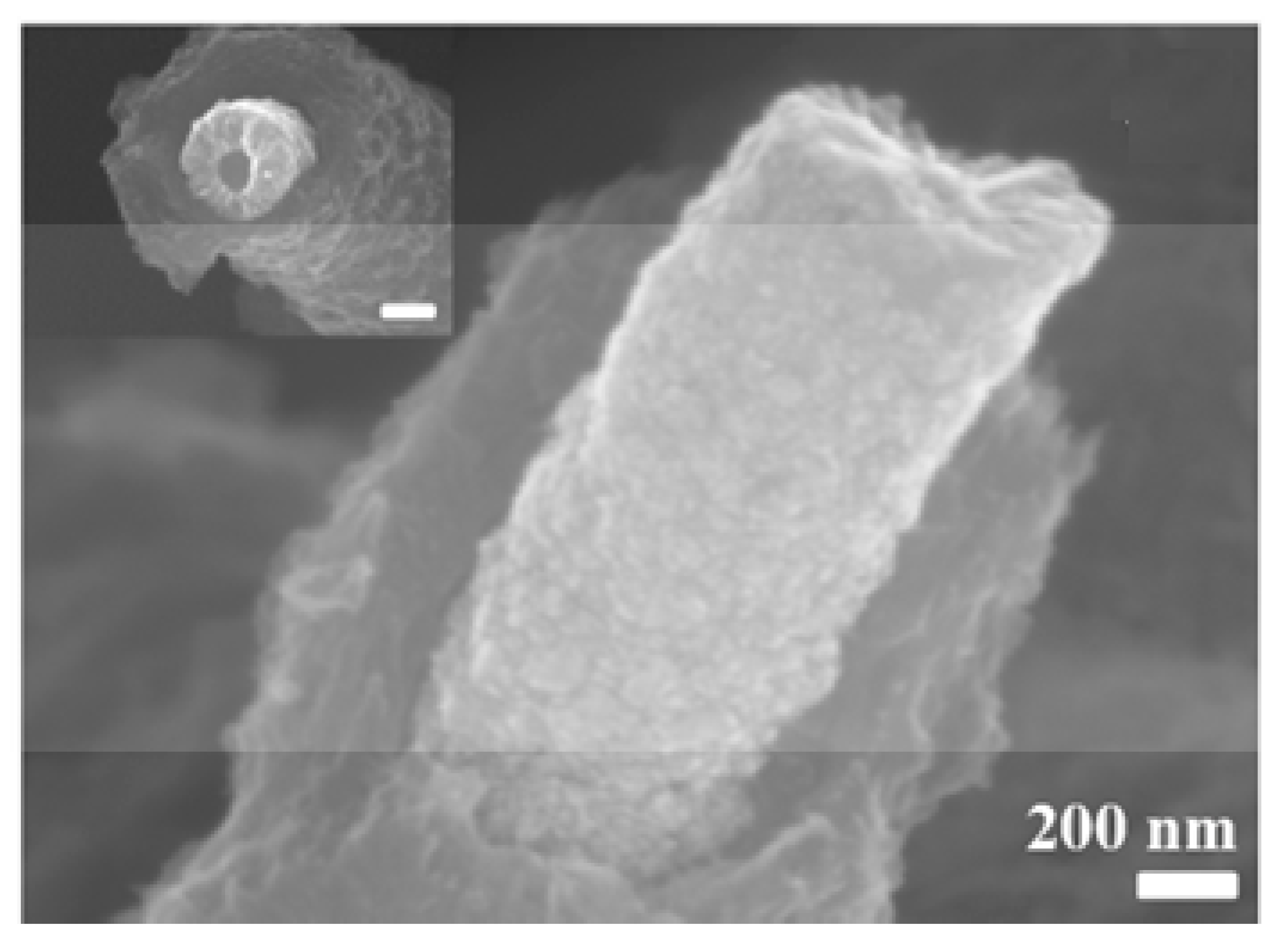

5. Morphology

6. Coatings

6.1. Metallic Coatings

6.1.1. Transition Metal Oxides

6.1.2. Other Metal Compounds

6.2. Carbon Coatings

6.2.1. Diamond

6.2.2. SiC

6.2.3. Nanocarbon

6.2.4. 1D Nanocarbon

6.2.5. Graphene-Based Films

- -

- by potentiometry—at 1 mA for 120 s (“J” sample, active mass = 90.8 μg);

- -

- by CVA—at 5 mV/s for 6 cycles (“CV” sample, active mass = 74.2 μg).

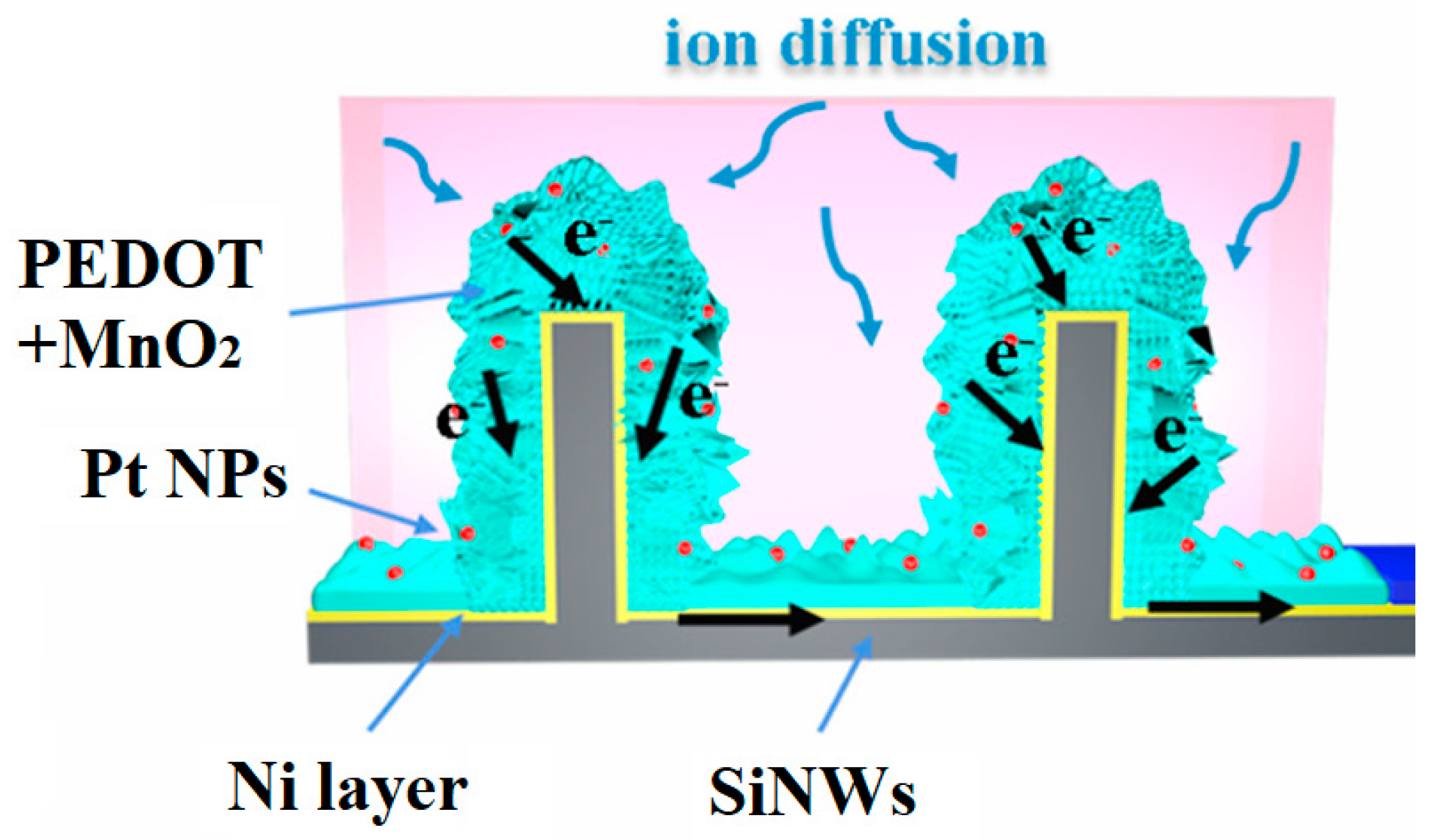

6.3. Polymer Coatings

6.3.1. PPy

6.3.2. PEDOT

6.3.3. Combined Polymers

6.3.4. PANI

6.4. Combined Coatings

6.5. Comparison

- -

- the smart design without consideration of the passivation/corrosion of the SiNWs in aqueous solution and the synergistic effects of the core–shell configuration and the combination of PsAg and rGO [53];

- -

- cracks on MnOx can effectively alleviate volume variations in MnOx during electrochemical cycling [59];

- -

- rGO underlayer used for NiCoSe coating [95].

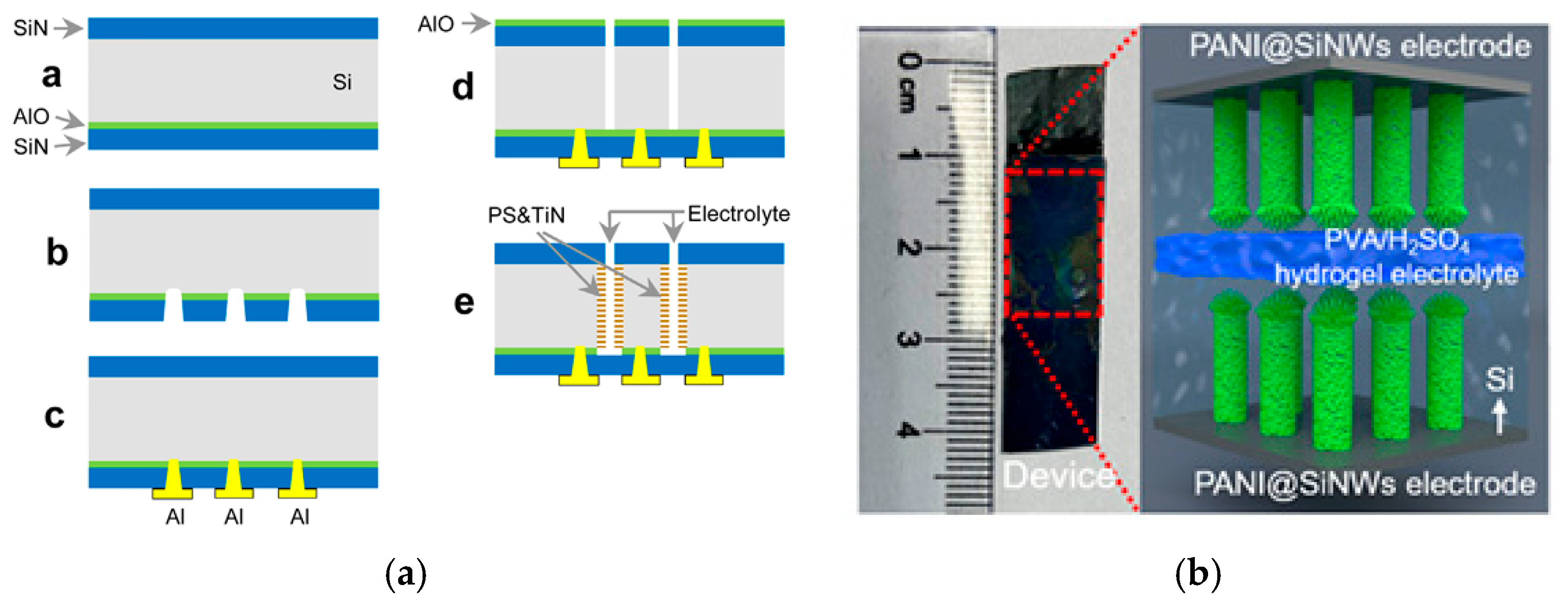

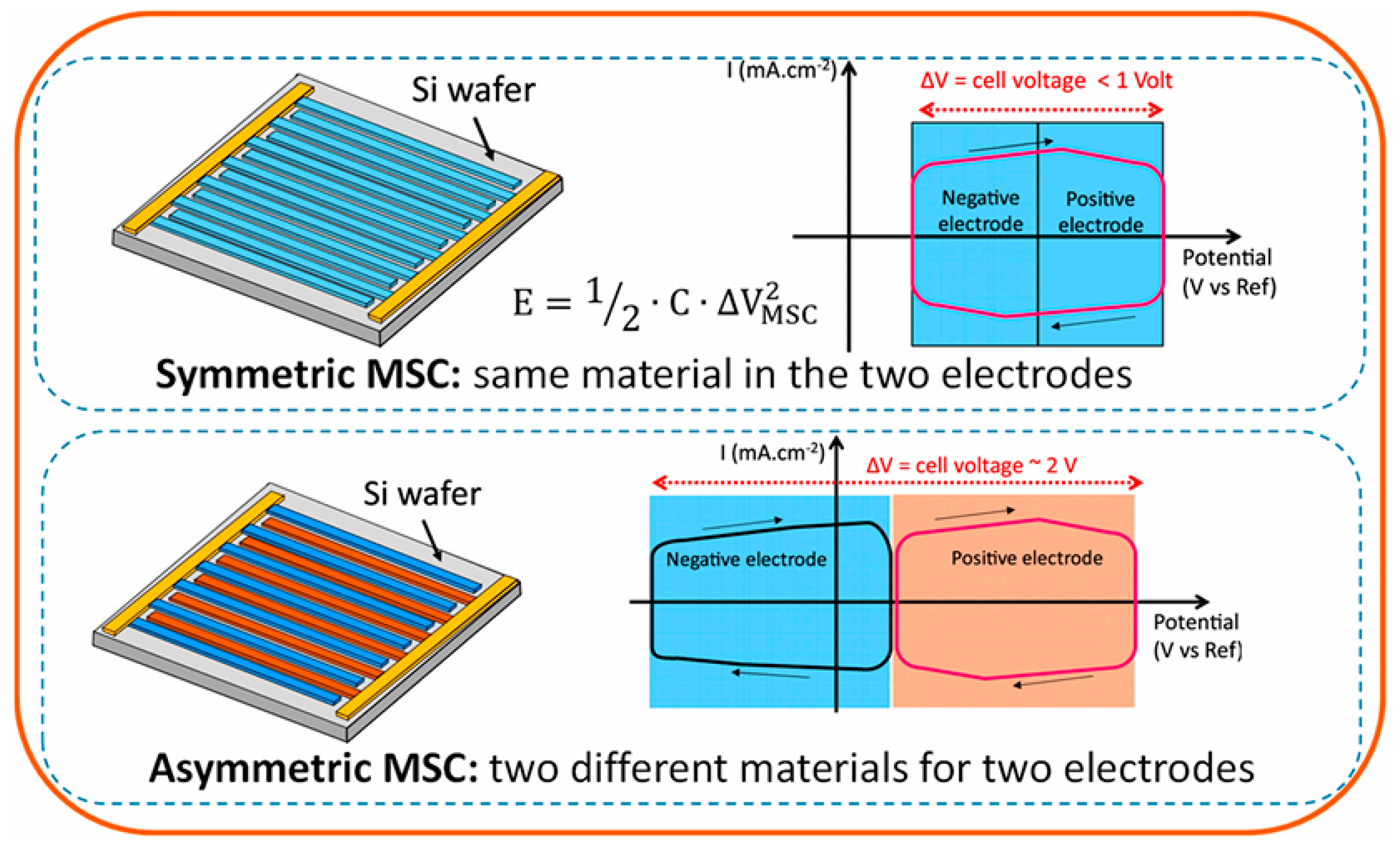

7. Devices

8. Conclusions

- •

- Aligned MACE-etched SiNWs are better than twisted ones synthesized by VLS.

- •

- Herringbone-like architecture of nanostructured silicon is preferred.

- •

- Nanopores in pSi are more successful compared to micropores.

- •

- The use of organic ionic liquids is preferable to aqueous electrolytes (quasi-solid-state electrolytes are promising).

- •

- The difficulty of completely impregnating the structure with the electrolyte;

- •

- The difficulty of completely covering long SiNWs/deep pSi with additional coatings;

- •

- The lengthened pathway for electron diffusion.

- •

- The cyclic stability, especially for Shen’s and Maboudian’s group approaches, should be additionally investigated;

- •

- More coatings (carbon, primarily graphene-based, conductive polymers, and metal compounds, especially oxides) should be tested to coat pSi;

- •

- The influence of DRIE depth on pSi capacitance should be studied.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| pSi | Porous silicon |

| SiNW | Silicon nanowire |

| AE | Anodic etching |

| DRIE | Deep reactive ion etching |

| MACE | Metal-assisted chemical etching |

| VLS | Vapor–liquid–solid |

| SiNR | Silicon nanorod |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| MAAE | Metal-assisted anodic etching |

| M | mol/L |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| SM | Supplementary materials |

| EDL | Electrical double layer |

| CVA | Cyclic voltammetry |

| GCD | Galvanostatic charge–discharge |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| GLC | Graphene-like coating |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TMAH | Tetramethylammonium hydroxide |

| ELD | Electroless layer deposition |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ALD | Atomic layer deposition |

| EPD | Electrophoretic deposition |

| SAED | Selected area electron diffraction |

| PMPyrrBTA | 1-methyl-1-propylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray |

| ECD | Electrochemical deposition |

| SiTNR | Silicon taper nanorod |

| N-carbon | N-doped carbon |

| PDOP | Polydopamine |

| OxP | Oxidative polymerization |

| MW | Microwave |

| DLC | Diamond-like carbon |

| FC | Fullerene-like carbon |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| FLG | Few-layer graphene |

| ElP | Electropolymerization |

| DHN | 2,6-dihydroxynaphthalene |

| SPD | Sharp pressure drop |

| PPy | Polypyrrole |

| PYR13TFSI | N-propyl-N-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide |

| PEDOT | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) |

| TBABF4 | Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate |

| N1114TFSI | Butyltrimethylammonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| PSS | Poly(styrenesulfonate) |

| PhP | Photo polymerization |

| GNW | Graphene nanowall |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| rGO | Reduced graphene oxide |

| EMIM-TFSI | 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

| TEABF4 | Tetraethylammonium tetrafluoroborate |

| Et3NH TFSI | Triethylammonium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide |

References

- Mateen, A.; Khan, A.J.; Zhou, Z.; Mujear, A.; Farid, G.; Yan, W.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Bao, Z. Silicon Nanowires via Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching for Energy Storage Applications. ChemSusChem 2024, 18, e202400777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, S.; Sindhuja, M. Advances in silicon nanowire applications in energy generation, storage, sensing, and electronics: A review. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 182001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Giri, P.K. Silicon nanowire heterostructures for advanced energy and environmental applications: A review. Nanotechnology 2016, 28, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, X.; Li, T.; Ge, J.; Li, Z. A Review on Cutting Edge Technologies of Silicon-Based Supercapacitors. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6650131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granitzer, P.; Rumpf, K. Porous silicon—A versatile host material. Materials 2010, 3, 943–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.X. Porous silicon: Morphology and formation mechanisms. In Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 65–133. [Google Scholar]

- Starkov, V. Production, properties, and application of porous silicon. All Mater. Encycl. Ref. Book 2009, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Geyer, N.; Werner, P.; De Boor, J.; Gösele, U. Metal-assisted chemical etching of silicon: A review. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.; Wittemann, J.V.; Senz, S.; Gösele, U. Silicon nanowires: A review on aspects of their growth and their electrical properties. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2681–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Wang, J.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Mateen, A.; Farid, G.; Peng, K.Q. Metal-assisted chemical etching of silicon in oxidizing HF solutions: Origin, mechanism, development, and black silicon solar cell application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2005744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jorné, J. Morphological stability analysis of porous silicon formation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1993, 140, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, L.T. Silicon quantum wire array fabrication by electrochemical and chemical dissolution of wafers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990, 57, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Collins, S. Porous silicon formation mechanisms. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 71, R1–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryachev, D.; Belyakov, L.; Sreseli, O. On the mechanism of porous silicon formation. Semiconductors 2000, 34, 1090–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, K.W. The mechanism of Si etching in fluoride solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Chorin, M.; Möller, F.; Koch, F. Nonlinear electrical transport in porous silicon. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.M.; Villalobos, J.; McNeill, P.; Prasad, J.; Cheek, R.; Kelber, J.; Estrera, J.; Stevens, P.; Glosser, R. Direct evidence for the amorphous silicon phase in visible photoluminescent porous silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 61, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, D.; Jiang, M. Annealing and amorphous silicon passivation of porous silicon with blue light emission. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2005, 252, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, S.; Mueller, L.; Kremin, C.; Hoffmann, M. Online monitoring of the passivation breakthrough during deep reactive ion etching of silicon using optical plasma emission spectroscopy. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2013, 23, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.A.; Faro, M.J.L.; Irrera, A. Silicon nanowires synthesis by metal-assisted chemical etching: A review. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bohn, P. Metal-assisted chemical etching in HF/H2O2 produces porous silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 2572–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, D.; Thompson, C.V. High-performance solid-state on-chip supercapacitors based on Si nanowires coated with ruthenium oxide via atomic layer deposition. J. Power Sources 2017, 341, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovskii, V.; Sibirev, N.; Harmand, J.; Glas, F. Growth kinetics and crystal structure of semiconductor nanowires. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 78, 235301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artoni, P.; Pecora, E.F.; Irrera, A.; Priolo, F. Kinetics of Si and Ge nanowires growth through electron beam evaporation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Tang, H.; Zhang, N.; Sun, Q. Amorphous Nickel Boride Deposited on Silicon Nanowires and Carbon Nanowall Templates for High-Performance Micro-supercapacitors. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencheikh, Y.; Harnois, M.; Jijie, R.; Addad, A.; Roussel, P.; Szunerits, S.; Hadjersi, T.; Abaidia, S.E.H.; Boukherroub, R. High performance silicon nanowires/ruthenium nanoparticles micro-supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 311, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradilla, D.; Gaboriau, D.; Bidan, G.; Gentile, P.; Boniface, M.; Dubal, D.; Gómez-Romero, P.; Wimberg, J.; Schubert, T.J.; Sadki, S. An innovative 3-D nanoforest heterostructure made of polypyrrole coated silicon nanotrees for new high performance hybrid micro-supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 13978–13985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.; Haye, E.; Achour, A.; Harnois, M.; Hadjersi, T.; Colomer, J.-F.; Pireaux, J.-J.; Lucas, S.; Boukherroub, R. High performance of 3D silicon nanowires array@CrN for electrochemical capacitors. Nanotechnology 2019, 31, 035407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lé, T.; Bidan, G.; Gentile, P.; Billon, F.; Debiemme-Chouvy, C.; Perrot, H.; Sel, O.; Aradilla, D. Understanding the energy storage mechanisms of poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-coated silicon nanowires by electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance. Mater. Lett. 2019, 240, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D.P.; Aradilla, D.; Bidan, G.; Gentile, P.; Schubert, T.J.; Wimberg, J.; Sadki, S.; Gomez-Romero, P. 3D hierarchical assembly of ultrathin MnO2 nanoflakes on silicon nanowires for high performance micro-supercapacitors in Li-doped ionic liquid. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboriau, D.; Aradilla, D.; Brachet, M.; Le Bideau, J.; Brousse, T.; Bidan, G.; Gentile, P.; Sadki, S. Silicon nanowires and nanotrees: Elaboration and optimization of new 3D architectures for high performance on-chip supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 81017–81027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboriau, D.; Boniface, M.; Valero, A.; Aldakov, D.; Brousse, T.; Gentile, P.; Sadki, S. Atomic layer deposition alumina-passivated silicon nanowires: Probing the transition from electrochemical double-layer capacitor to electrolytic capacitor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13761–13769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soam, A.; Parida, K.; Kumar, R.; Dusane, R.O. Silicon-MnO2 core-shell nanowires as electrodes for micro-supercapacitor application. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 18914–18923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Halvorsen, E.; Ohlckers, P.; Müller, L.; Leopold, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Grigoras, K.; Ahopelto, J.; Prunnila, M.; Chen, X. Ternary composite Si/TiN/MnO2 taper nanorod array for on-chip supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 248, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Müller, L.; Hoffmann, M.; Chen, X. Taper silicon nano-scaffold regulated compact integration of 1D nanocarbons for improved on-chip supercapacitor. Nano Energy 2017, 41, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soam, A.; Arya, N.; Singh, A.; Dusane, R. Fabrication of silicon nanowires based on-chip micro-supercapacitor. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 678, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogotsi, Y.; Penner, R.M. Energy storage in nanomaterials–capacitive, pseudocapacitive, or battery-like? ACS Nano 2018, 12, 2081–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Burke, A.F. Electrochemical capacitors: Materials, technologies and performance. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 36, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, P.T.; Heineman, W.R. Cyclic voltammetry. J. Chem. Educ. 1983, 60, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletcher, D.; Greff, R.; Peat, R.; Peter, L.; Robinson, J. Instrumental Methods in Electrochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zanello, P.; Nervi, C.; De Biani, F.F. Inorganic Electrochemistry: Theory, Practice and Application; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, L.-Q.; Minhas-Khan, A.; Tian, X.; Hercule, K.M.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Lin, X.; Xu, X. Synergistic interaction between redox-active electrolyte and binder-free functionalized carbon for ultrahigh supercapacitor performance. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Z. Understanding supercapacitors based on nano-hybrid materials with interfacial conjugation. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2013, 23, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Gao, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J. Editors’ choice—Review—Impedance response of porous electrodes: Theoretical framework, physical models and applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 166503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, B.-A.; Munteshari, O.; Lau, J.; Dunn, B.; Pilon, L. Physical interpretations of Nyquist plots for EDLC electrodes and devices. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, M.Y.; Johan, B.A.; Abdallah, M.; Hossain, M.E.; Aziz, M.A.; Baroud, T.N.; Drmosh, Q.A. Understanding the behavior of supercapacitor materials via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: A review. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202400007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, S.; Latham, R.; Schlindwein, W. Supercapacitor devices using porous silicon electrodes. Ionics 1999, 5, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarapalli, R.R.; Szunerits, S.; Coffinier, Y.; Shelke, M.V.; Boukherroub, R. Glucose-derived porous carbon-coated silicon nanowires as efficient electrodes for aqueous micro-supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 4298–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, J.P.; Wang, S.; Rossi, F.; Salviati, G.; Yiu, N.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Selective ultrathin carbon sheath on porous silicon nanowires: Materials for extremely high energy density planar micro-supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1843–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thissandier, F.; Gentile, P.; Pauc, N.; Hadji, E.; Le Comte, A.; Crosnier, O.; Bidan, G.; Sadki, S.; Brousse, T. Highly N-doped silicon nanowires as a possible alternative to carbon for on-chip electrochemical capacitors. Electrochemistry 2013, 81, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, J.P.; Vincent, M.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Silicon carbide coated silicon nanowires as robust electrode material for aqueous micro-supercapacitor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 163901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, M.; Ni, X. Modified silicon nanowires@ polypyrrole core-shell nanostructures by poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for high performance on-chip micro-supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 487, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, T.; Wei, X.; Li, S. Facile synthesis of metal oxide and conductive polymers around silicon nanowire arrays for a high-performance aqueous supercapacitor. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 2596–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, N.; Umar, A.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Bai, P.; Frans de Rooij, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G. In situ construction of the coral-like polyaniline on the aligned silicon nanowire arrays for silicon substrate on-chip supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 11792–11802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortaboy, S.; Alper, J.P.; Rossi, F.; Bertoni, G.; Salviati, G.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. MnOx-decorated carbonized porous silicon nanowire electrodes for high performance supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlovets, D.M.; Naumov, A.P.; Korotitsky, V.I.; Starkov, V.V. Nanoporous Silicon with Graphene-like Coating for Pseudocapacitor Application. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esarev, I.V.; Agafonov, D.V.; Surovikin, Y.V.; Nesov, S.N.; Lavrenov, A.V. On the causes of non-linearity of galvanostatic charge curves of electrical double layer capacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 390, 138896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradilla, D.; Gao, F.; Lewes-Malandrakis, G.; Müller-Sebert, W.; Gentile, P.; Boniface, M.; Aldakov, D.; Iliev, B.; Schubert, T.J.; Nebel, C.E. Designing 3D multihierarchical heteronanostructures for high-performance on-chip hybrid supercapacitors: Poly (3, 4-(ethylenedioxy) thiophene)-coated diamond/silicon nanowire electrodes in an aprotic ionic liquid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18069–18077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wei, M.; Shen, X. MnOx Embedded in Silicon Nanowire Arrays for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 35, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Li, S.; Li, H. Solution-processable hierarchical SiNW/PEDOT/MnOx electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 2894–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, A.; Mery, A.; Gaboriau, D.; Gentile, P.; Sadki, S. One step deposition of PEDOT–PSS on ALD protected silicon nanowires: Toward ultrarobust aqueous microsupercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 2, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desplobain, S.; Gautier, G.; Semai, J.; Ventura, L.; Roy, M. Investigations on porous silicon as electrode material in electrochemical capacitors. Phys. Status Solidi C 2007, 4, 2180–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, N.; Azevedo, A.; Beloto, A.; Amaral, M.; Almeida, F.; Oliveira, F.; Silva, R. Nanodiamond films growth on porous silicon substrates for electrochemical applications. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2005, 14, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlovets, D.M.; Starkov, V.V.; Ulianova, V.V. N-doped graphene-like coating for improved microcapacitance of nanoporous silicon. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 198, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlovets, D.M.; Ulianova, V.V.; Starkov, V.V.; Knyazev, M.A. Photonic annealing effect on nanoporous silicon structures and their electrochemical capacitance. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 27184–27189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-H.; Chang, C.-T.; Wang, C.-C.; Parwaiz, S.; Lai, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Lu, S.-Y.; Chueh, Y.-L. Few-layer graphene sheet-passivated porous silicon toward excellent electrochemical double-layer supercapacitor electrode. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulai, F.; Hadjersi, T.; Ifires, M.; Khen, A.; Rachedi, N. Enhancement of electrochemical capacitance of silicon nanowires arrays (SiNWs) by modification with manganese dioxide MnO2. Silicon 2019, 11, 2799–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Shao, M.; Yang, L.; Zhuo, S.; Ye, S.; Lee, S.-T. Manganese dioxide modified silicon nanowires and their excellent catalysis in the decomposition of methylene blue. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 063104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulai, F.; Cherchour, N.; Messaoudi, B.; Zerroual, L. Electrosynthesis and characterization of nanostructured MnO2 deposited on stainless steel electrode: A comparative study with commercial EMD. Ionics 2017, 23, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Nanostructured MnO2 as electrode materials for energy storage. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, D.; Brousse, T.; Long, J. Manganese oxides: Battery materials make the leap to electrochemical capacitors. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2008, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-W.; Bak, S.-M.; Lee, C.-W.; Jaye, C.; Fischer, D.A.; Kim, B.-K.; Yang, X.-Q.; Nam, K.-W.; Kim, K.-B. Structural changes in reduced graphene oxide upon MnO2 deposition by the redox reaction between carbon and permanganate ions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, Q.; Xu, W.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y. Long cyclic life in manganese oxide-based electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18078–18088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, T.; Shen, X.; Zhu, M. Passivation of silicon nanowires with Ni particles and a PEDOT/MnOx composite for high-performance aqueous supercapacitors. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Bao, M.; Ni, X. A novel surface modification of silicon nanowires by polydopamine to prepare SiNWs/NC@NiO electrode for high-performance supercapacitor. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 406, 126660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Qiu, M.; Qi, X.; Yang, L.; Yin, J.; Hao, G.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Zhong, J. Electrochemical properties of high-power supercapacitors using ordered NiO coated Si nanowire array electrodes. Appl. Phys. A 2011, 104, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoras, K.; Keskinen, J.; Grönberg, L.; Ahopelto, J.; Prunnila, M. Coated porous Si for high performance on-chip supercapacitors. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 557, 012058. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoras, K.; Keskinen, J.; Grönberg, L.; Yli-Rantala, E.; Laakso, S.; Välimäki, H.; Kauranen, P.; Ahopelto, J.; Prunnila, M. Conformal titanium nitride in a porous silicon matrix: A nanomaterial for in-chip supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2016, 26, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ohlckers, P.; Müller, L.; Leopold, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Grigoras, K.; Ahopelto, J.; Prunnila, M.; Chen, X. Nano fabricated silicon nanorod array with titanium nitride coating for on-chip supercapacitors. Electrochem. Commun. 2016, 70, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon-Roman, A.; Cuate-Gomez, D. Graphene nanoflakes and carbon nanotubes on porous silicon layers by spin coating, for possible applications in optoelectronics. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 292, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenych, I.B.; Aksimentyeva, O.I.; Monastyrskii, L.S.; Horbenko, Y.Y.; Partyka, M.V.; Luchechko, A.P.; Yarytska, L.I. Effect of graphene oxide on the properties of porous silicon. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, R.; De Stefano, L.; Terracciano, M.; Rea, I. Porous silicon optical devices: Recent advances in biosensing applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, H.G. Efficient room temperature hydrogen gas sensing based on graphene oxide and decorated porous silicon. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 15966–15972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.T.; Nayef, U.M.; Hussien, A.M.A. Synthesis of graphene on porous silicon for vapor organic sensor by using photoluminescence. Optik 2019, 180, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, A.M.A.; Hussein, H.T.; Nayef, U.M.; Mahdi, M.H. Study of changing the intensity of photoluminescence spectra as a humidity sensor for graphene on porous silicon. Optik 2019, 193, 163015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.A.; Kadhim, R.G.; Wasna’a, M.A. Effect of multiwalled carbon nanotubes incorporation on the performance of porous silicon photodetector. Optik 2016, 127, 8144–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradilla, D.; Gao, F.; Lewes-Malandrakis, G.; Müller-Sebert, W.; Gaboriau, D.; Gentile, P.; Iliev, B.; Schubert, T.; Sadki, S.; Bidan, G. A step forward into hierarchically nanostructured materials for high performance micro-supercapacitors: Diamond-coated SiNW electrodes in protic ionic liquid electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2016, 63, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachedi, N.; Hadjersi, T.; Moulai, F.; Dokhane, N. Diamond-like carbon-coated silicon nanowires as a supercapacitor electrode in an aqueous LiClO4 electrolyte. Silicon 2022, 14, 2533–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotov, V.; Nesov, S.; Ponomareva, I.; Knyazev, E.; Ivlev, K.; Stenkin, Y.A.; Roslikov, V. The formation of nanocomposites carbon nanotubes/porous silicon for supercapacitor electrodes. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Romanitan, C.; Varasteanu, P.; Mihalache, I.; Culita, D.; Somacescu, S.; Pascu, R.; Tanasa, E.; Eremia, S.A.; Boldeiu, A.; Simion, M. High-performance solid state supercapacitors assembling graphene interconnected networks in porous silicon electrode by electrochemical methods using 2, 6-dihydroxynaphthalen. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Toan, N.; Tuoi, T.T.K.; Li, J.; Inomata, N.; Ono, T. Liquid and solid states on-chip micro-supercapacitors using silicon nanowire-graphene nanowall-pani electrode based on microfabrication technology. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 131, 110977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradilla, D.; Bidan, G.; Gentile, P.; Weathers, P.; Thissandier, F.; Ruiz, V.; Gómez-Romero, P.; Schubert, T.J.; Sahin, H.; Sadki, S. Novel hybrid micro-supercapacitor based on conducting polymer coated silicon nanowires for electrochemical energy storage. Rsc Adv. 2014, 4, 26462–26467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Ma, B.; Chen, L.; Zhao, J. High efficiency conjugated polymer/Si hybrid solar cells with tetramethylammonium hydroxide treatment. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Li, S.; Li, H. Polypyrrole embedded in nickel-cobalt sulfide nanosheets grown on nickel particles passivated silicon nanowire arrays for high-performance supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Sun, S.; Wei, X. Co-electrodeposition hybrid reduced graphene oxide and nickel-cobalt selenide nanosheets on silicon nanowires for high-performance supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, A.K.; Lakshmanan, C.; Viswanath, R.; Poddar, C.; Mathews, T. Electrochemical studies on wafer-scale synthesized silicon nanowalls for supercapacitor application. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2020, 43, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, N.; Brachet, M.; Thissandier, F.; Le Bideau, J.; Gentile, P.; Bidan, G.; Brousse, T.; Sadki, S. Wide-voltage-window silicon nanowire electrodes for micro-supercapacitors via electrochemical surface oxidation in ionic liquid electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2014, 41, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Lewes-Malandrakis, G.; Wolfer, M.T.; Müller-Sebert, W.; Gentile, P.; Aradilla, D.; Schubert, T.; Nebel, C.E. Diamond-coated silicon wires for supercapacitor applications in ionic liquids. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2015, 51, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lé, T.; Gentile, P.; Bidan, G.; Aradilla, D. New electrolyte mixture of propylene carbonate and butyltrimethylammonium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide (n1114 tfsi) for high performance silicon nanowire (sinw)-based supercapacitor applications. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 254, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, A.A.; Arrigo, A.; Lo Faro, M.J.; Nastasi, F.; Irrera, A. 2D Fractal Arrays of Ultrathin Silicon Nanowires as Cost-Effective and High-Performance Substrate for Supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2400080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-C.; Chong, C.-W.; Wang, S.-B.; Heh, D.; Tseng, C.-A.; Huang, Y.-F.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chen, K.-H.; Lin, C.-F.; Lee, J.-H. High K nanophase zinc oxide on biomimetic silicon nanotip array as supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 1422–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchak, O.; Keller, C.; Lapertot, G.; Salaün, M.; Danet, J.; Chen, Y.; Bendiab, N.; Pépin-Donat, B.; Lombard, C.; Faure-Vincent, J. Scalable chemical synthesis of doped silicon nanowires for energy applications. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22504–22514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamri, S.; Raouadi, M. Improved capacitance of NiO and nanoporous silicon electrodes for micro-supercapacitor application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2025, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakardjieva, S.; Bezdička, P.; Grygar, T.; Vorm, P. Reductive dissolution of microparticulate manganese oxides. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2000, 4, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, K.-H. Fabrication of microcapacitors using conducting polymer microelectrodes. J. Power Sources 2003, 124, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, D.; Brunet, M.; Durou, H.; Huang, P.; Mochalin, V.; Gogotsi, Y.; Taberna, P.-L.; Simon, P. Ultrahigh-power micrometre-sized supercapacitors based on onion-like carbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-S.; Feng, X.; Cheng, H.-M. Recent advances in graphene-based planar micro-supercapacitors for on-chip energy storage. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2014, 1, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fan, X.; Xiong, Q.; Xiong, C. Multi-dimensional optimization and diversified applications of carbon fiber-based flexible electrode materials–synergistic design of cross-type supercapacitors and electrolyte systems. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1038, 182768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. On-chip microsupercapacitors: From material to fabrication. Energy Technol. 2019, 7, 1900820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, H.; Hu, T.; Fan, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Emerging 2D MXenes for supercapacitors: Status, challenges and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6666–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, R.; De Mierry, P.; Ballutaud, D.; Aucouturier, M.; Mathiot, D. Hydrogen diffusion and passivation processes in p-and n-type crystalline silicon. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, K.H.; Roussel, P.; Lethien, C. Advances on microsupercapacitors: Real fast miniaturized devices toward technological dreams for powering embedded electronics? ACS Omega 2023, 8, 8977–8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolayemi, B.; Buvat, G.; Roussel, P.; Lethien, C. Emerging capacitive materials for on-chip electronics energy storage technologies. Batteries 2024, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Michailidis, N. Printable conductive inks used for the fabrication of electronics: An overview. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 502009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Silva, U.; Cajero-Sotelo, L.; Nicho, M.; Antunez, E.E.; Escobedo-Alatorre, J.; Sandoval-Espino, J.; Marban-Salgado, J.; Diaz-Guillen, M. Biopolymeric separator for capacitors based on porous silicon. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 200, 112597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.; Lee, H.; Chae, O.B. Overcoming Challenges in Silicon Anodes: The Role of Electrolyte Additives and Solid-State Electrolytes. Micromachines 2025, 16, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ni, Z.; Geng, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, H.; Li, Y.; Xiong, S.; Feng, J. Advancements in Electrolytes: From Liquid to Solid for Low-Cost and High-Energy-Density Micro-Sized Silicon-Based Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2502284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | C, mF/cm2 | Measured | Matrix (Method) | Coating (Method) | Electrolyte | Cap. Retention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Cycles | ||||||

| [36] | 0.013 | at 10 mV/s | SiNWs (VLS) | – | EMIM-TFSI * | 98 | 1k |

| [96] | 0.021 | at 10 mV/s | 11.9 μm SiNWs (MACE) | – | 1 M TEABF4 | 83 | 0.5k |

| [97] | 0.031 | at 0.25 mA/cm2 | 20 μm SiNWs (VLS) | – | EMIM-TFSI | – | – |

| [32] | 0.038 | at 0.25 mA/cm2 | 5 μm SiNWs (VLS) | 3 nm Al2O3 (ALD) | EMIM-TFSI | 96 | 1000k |

| [50] | 0.051 | at 5 μA/cm2 | 50 μm SiNWs (VLS) | – | TEABF4 * | 97 | 200k |

| [98] | 0.108 | at 5 mV/s | 5 μm SiNWs (VLS) | diamond (CVD) | PMPyrr-TFSI | ~93 | 10k |

| [99] | 0.18 | at 2.2 mA/cm2 | SiNWs (VLS) | – | N1114TFSI | 70 | 3000k |

| [47] | 0.2 | at 10 mV/s | pSi (AE) | – | 0.25 M TEABF4 | – | – |

| [100] | 0.274 | at 50 mV/s | 2.7 μm SiNWs (MACE) | – | 0.1 M Li2SO4 | 74 | 1k |

| [101] | 0.3 | – | 1 μm SiNWs (VLS) | 20 nm ZnO (ALD); 10 nm Al2O3(ALD) | – | – | – |

| [62] | 0.32 | – | 43 μm pSi (AE) | Au | 20% H2SO4 | – | – |

| [102] | 0.75 | at 0.14 mA/cm2 | SiNW powder (VLS) | – | 0.5 M TBABF4 | 80 | 1000k |

| [63] | 0.99 | at 100 mV/s | pSi (AE) | nanodiamond (CVD) | 0.1 M KCl | – | – |

| [31] | 1.25 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 50 μm SiNTrs (2-step VLS) | – | – | 80 | 1000k |

| [87] | 1.5 | at 10 mA/cm2 | 50 μm SINWs (VLS) | diamond (CVD) | Et3NH-TFSI * | 65 | 1000k |

| [79] | 1.55 | at 2 mV/s | 20 μm SiNRs (DRIE) | 30 nm TiN (ALD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 95.2 | 2k |

| [51] | 1.7 | at 50 mV/s | SINWs (MACE) | SiC (CVD) | 1 M KCl | 95 | 1k |

| [88] | 2 | at 0.01 mA/cm2 | 60 μm SINWs (MACE) | DLC (EPD) | 0.5 M LiClO4 | 90 | 16k |

| [33] | 2.1 | at 0.04 mA/cm2 | SINWs (VLS) | MnO2 (EPD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 90 | 5k |

| [77] | 4.38 * | – | 6 μm pSi (AE) | TiN (ALD) | TEABF4 | stable | 5.5 k |

| [61] | 6.4 | at 20 mV/s | 50 μm SINWs (VLS) | Al2O3 (ALD); PEDOT-PSS (drop casting) | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | 95 | 500 k |

| [66] | 8.16 | at 1000 mV/s | 15 μm pSi (AE) | FLG (Ni-assist CVD) | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | 130 | 10k |

| [58] | 8.5 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 50 μm SINWs (VLS) | diamond (CVD); PEDOT (ElP) | N1114TFSI | 80 | 15k |

| [103] | 9.64 | at 1 mA/cm2 | pSi (AE) | NiO (sol-gel) | 1 M NaOH | 97 | 5k |

| [30] | 13 | at 0.4 mA/cm2 | 50 μm SINWs (VLS) | MnO2 (ELD) | LiClO4-PMPyrrBTA | 91 | 5k |

| [27] | 14 | at 1 mA/cm2 | SiNTrs (VLS) | Ppy (ElP) | PYR13TFSI | 70 | 10k |

| [29] | 17 | at 100 mV/s | 10 μm SINWs (VLS) | PEDOT (ECD) | TBABF4 | – | – |

| [22] | 19 | at 5 mV/s | 6 μm SINWs (MAAE) | RuO2 (ALD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 92 | 10k |

| [67] | 21.3 | at 1000 mV/s | 10 μm SINWs (MACE) | MnO2 (ELD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | – | – |

| [48] | 25.6 | at 0.1 mA/cm2 | 17 μm SINWs MACE | nanocarbon (glucose pyrolysis) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 75 | 25k |

| [90] | 30 | at 0.5 A/g | 5 μm pSi | GLC (DHN pyrolysis) | PVA-H2SO4 | 75 | 1k |

| [26] | 36.25 | at 1 mA/cm2 | SiNWs (VLS) | Ru NPs (ELD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 80 | 25k |

| [34] | 81.6 | at 5 mV/s | ~5 μm SiTNR (DRIE) | TiN (ALD); MnO2 (ELD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 95.7 | 5k |

| [56] | 87 | at 5 mV/s | 80 μm pSi (AE) | GLC (CVD) | 3 M H2SO4 | 100 | 15k |

| [54] | 95.8 | at 10 mV/s | 5.5 μm SINWs (MACE) | PANI (OxP) | 1 M H2SO4 | 71.8 | 2k |

| [53] | 100.98 | at 1.5 mA/cm2 | 5.6 μm SINWs (MACE+TMAH) | PEDOT + MnO2 (ECD); rGO (ELD); AgNWs + PEDOT-PSS (spin-coating) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 81 | 2k |

| [52] | 106.1 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 17 μm SINWs (MACE) | PPy (OxP); PEDOT (PhP) | PYR13TFSI | 80.2 | 5k |

| [75] | 110 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 10 μm SINWs (MACE) | N-carbon (PDOP pyrolysis); NiO (ELD) | 6 M KOH | 81 | 4k |

| [35] | 123 192 | at 1000 mV/s at 1 mV/s | ~20 μm SiTNRs (DRIE) | FC-CNT (CVD) | H2SO4 | 102 | 5k |

| [91] | 130 | at 10 mV/s | 10 μm SINWs (MACE) | GNWs (CVD); PANI (ElP) | PVA-H2SO4 | 80 | 2k |

| [64] | 145 | at 5 mV/s | 80 μm pSi (AE) | N-GLC (CVD) | 3M H2SO4 | 93 | 20k |

| [25] | 165.7 | at 0.1 mA/cm2 | several μm SINWs (VLS) | NiB (ELD) | PVA-Na2SO4 | 93 | 10k |

| [28] | 180 31.8 | at 5 mV/s at 1.6 mA/cm2 | SiNWs (VLS) | CrN (magnetron sputtering) | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | 92 | 15k |

| [74] | 207.43 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 6 μm SiNWs (MACE+TMAH) | Ni + PEDOT + MnO2 (ECD co-deposition); Pt NPs (ELD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 95 | 5k |

| [49] | 325 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 120 μm SINWs (MACE) | nanocarbon (CVD) | EMIM-TSFI | 83 | 5k |

| [59] | 328.6 | at 1 mA/cm2 | 10 μm SINWs (MACE+TMAH) | Ni (ECD); MnO2 (ECD) | 1 M Na2SO4 | 79 | 7k |

| [60] | 352 | at 2 mA/cm2 | several μm SINWs (MACE + TMAH) | Ni (ECD), PEDOT (ElP), Pt NPs (ELD); MnO2 (ELD) AgNWs+PEDOT-PSS (spin-coating) | 85 | 2k | |

| [55] | 381 | at 4 mA/cm2 | 80 μm SINWs (MACE) | nanocarbon (CVD); MnOx (ELD) | 0.1 M EMIM-TSFI | 84 | 5k |

| [95] | 1973 | 0.87 A/cm2 | 10 μm SiNWs (MACE + TMAH) | Ni (ECD); NiCoSe-rGO (ECD) | 6 M KOH | 80.5 | 2k |

| Coating | Characteristic | Advantage | Disadvantage and/or Expectations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiB, CrN | pseudocapacitive | high capacitance | the capacitance of crystalline NiB needs to be explored |

| MnO2 | pseudocapacitive | ELD is compatible with microelectronic technology | moderate capacitance |

| MnOx with underlayer (TiN or carbon) | highly conductive underlayer | mentioned above + high or ultra-high capacitance | low cyclic stability |

| Carbon | improved charge transfer, good adhesion | high capacitance, high cyclic stability (for pSi) | CVD methods are poorly compatible with microelectronic technology |

| PEDOT-PSS | gelationous-like structure | ultra-high long-term cyclic | moderate capacitance |

| PANI with GNW underlayer | synergetic effect of both coatings | high capacitance | low cyclic stability |

| In combined coatings: | |||

| Pt NPS, rGO | improved charge transfer | ultra-high capacitance | long-term cyclic tests need to be carried out |

| NiCoSe | porous structure facilitates ionic diffusion | ||

| MnOx | cracks on the MnOx facilitate electrolyte penetration | ||

| Ref. | Celectrode, mF/cm2 | Device | Cdevice, mF/cm2 | Edevice, mWh/cm2 | Pdevice, mW/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] | 100.98 (at 1.5 mA/cm2) | symmetric | 24.7 (at 1 mA/cm2) | 0.0034 | 2.652 |

| [52] | 106.1 (at 1 mA/cm2) | symmetric | 46.5 (at 0.5 mA/cm2) | 0.0146 | 0.375 |

| [35] | 123 (at 1000 mV/s) 192 (at 1 mV/s) | symmetric | 178 (at 5 mV/s) | 0.0115 0.0096 | 2 34.7 |

| [91] | 130 (at 10 mV/s) | liquid state solid state | 84.4 (at 100 mV/s) | 0.0117 0.0108 | 0.42 0.782 |

| [74] | 207.43 (at 1 mA/cm2) | symmetric | 64 (at 1 mA/cm2) | 0.2503 1.5115 | 0.0103 0.006 |

| [59] | 328.6 (at 1 mA/cm2) | asymmetric | 95 (at 1 mA/cm2) | 0.021 0.00835 | 0.7998 7.9446 |

| [55] | 381 (at 4 mA/cm2) | symmetric | 49 (at 2 mA/cm2) | 0.146 * 0.0204 * | 0.128 * 14.4 * |

| [95] | 1973 (0.87 A/cm2) | asymmetric | 273 * (at 2.06 mA/cm2) | 0.109 * 0.034 * | 1.6 * 16.4 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sedlovets, D.M. Porous Silicon and Silicon Nanowires for On-Chip Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231826

Sedlovets DM. Porous Silicon and Silicon Nanowires for On-Chip Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231826

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedlovets, Daria M. 2025. "Porous Silicon and Silicon Nanowires for On-Chip Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231826

APA StyleSedlovets, D. M. (2025). Porous Silicon and Silicon Nanowires for On-Chip Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1826. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231826