Green Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Asafoetida and Their Antibacterial Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Instruments

2.3. CQDs and Cu-CQDs Synthesis

2.4. Antibacterial Evaluation

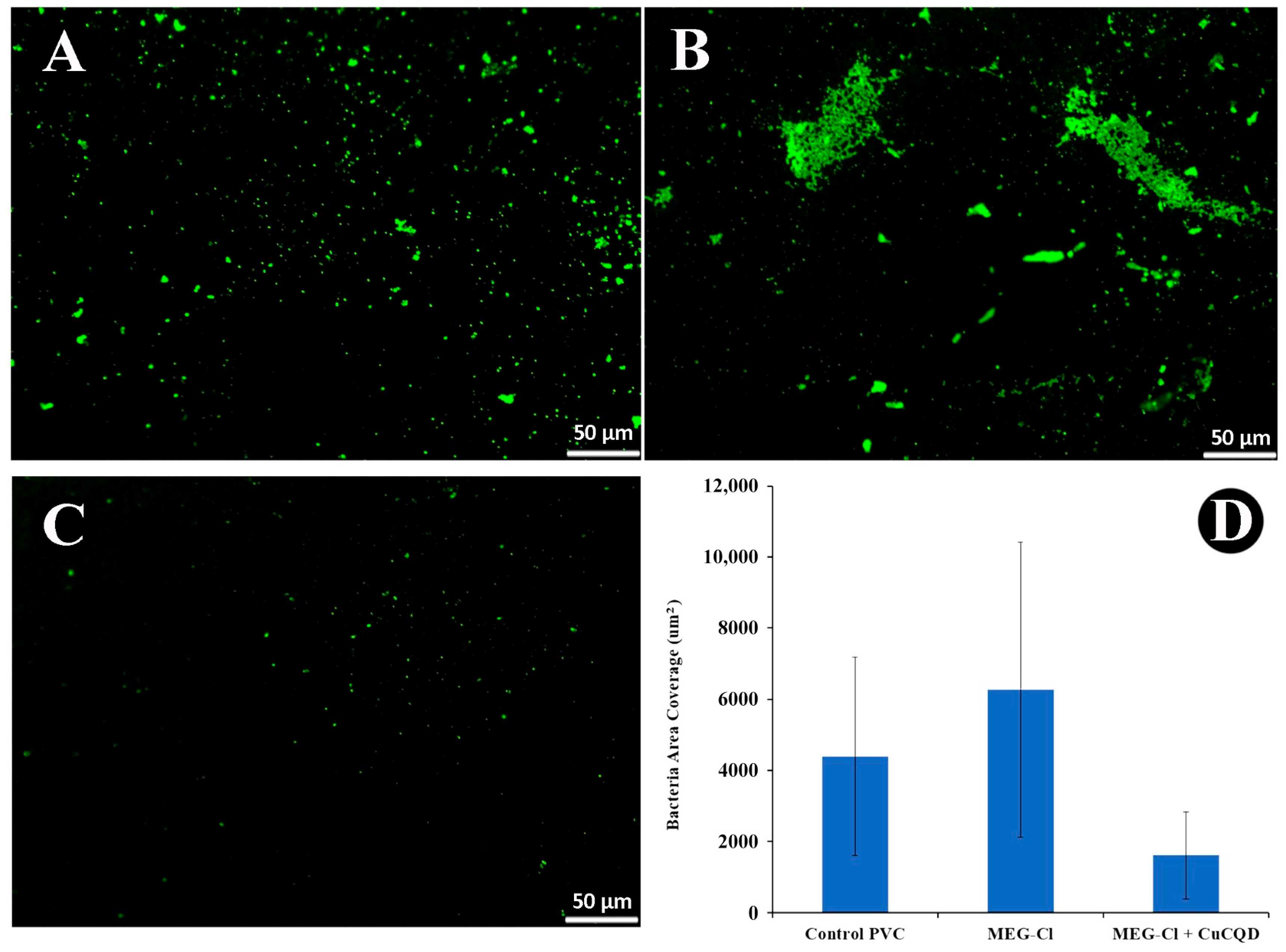

2.5. Modification of Plastic

2.6. Antibacterial Evaluation of Modified PVC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spectroscopic Evaluation of CQDs

3.2. Microscopic Evaluations of CQDs

3.3. Antibacterial Activities of As-Prepared CQDs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscope |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| CQDs | Carbon quantum dots |

| Cu-CQDs | Copper-doped carbon quantum dots |

| CAUTIs | catheter-associated urinary tract infections |

| PVC | Poly vinyl chloride |

| MEG-Cl | 3-(3-(trichlorosilyl)propoxy)propanoyl chloride |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| GFP | Green fluorescence protein |

References

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Liang, W.; Meziani, M.J.; Sun, Y.P.; Yang, L. Carbon Dots as Potent Antimicrobial Agents. Theranostics 2020, 10, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, L.; Xue, S.; Qu, D.; An, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Recent advances of carbon dots as new antimicrobial agents. SmartMat 2022, 3, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Su, R.; Li, P.; Su, W. Fluorescent Carbon Dot–Curcumin Nanocomposites for Remarkable Antibacterial Activity with Synergistic Photodynamic and Photothermal Abilities. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 6703–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Deb Dutta, S.; Lim, K.-T.; Kim, J. Wet chemistry-based processing of tunable polychromatic carbon quantum dots for multicolor bioimaging and enhanced NIR-triggered photothermal bactericidal efficacy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Ding, J. Antibacterial carbon dots. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 30, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, Z.M.; Budimir Filimonovic, M.D.; Milivojevic, D.D.; Kovac, J.; Todorovic Markovic, B.M. Antibacterial and Antibiofouling Activities of Carbon Polymerized Dots/Polyurethane and C(60)/Polyurethane Composite Films. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, P.; Puri, S.; Kosurkar, P. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles synthesized using a traditional phytoproduct, Asafoetida gum against periodontal opportunistic pathogens. Ann. For. Res. 2022, 65, 5134–5141. [Google Scholar]

- Devanesan, S.; Ponmurugan, K.; AlSalhi, M.S.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using a Traditional Phytoproduct, Asafoetida Gum. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 4351–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Ramezani, Z. (Eds.) Quantum Dots in Viral and Bacterial Detection. In Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2023; Volume 22, pp. 142–174. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Ramezani, Z. Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine; Burlington House: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Lin, L.; Wang, D.; Feng, L. Copper-doped cherry blossom carbon dots with peroxidase-like activity for antibacterial applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27873–27882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etefa, H.F.; Tessema, A.A.; Dejene, F.B. Carbon Dots for Future Prospects: Synthesis, Characterizations and Recent Applications: A Review (2019–2023). C 2024, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Soleymani, A.; Khoshkaram, M.; Cheng, Q. Asafoetida, god's food, a natural medicine. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2021, 11, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Q. Asafoetida, natural medicine for future. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 17, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazmand, R.; Razavizadeh, B.M. Ferula asafoetida: Chemical composition, thermal behavior, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leaf and gum hydroalcoholic extracts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, K.A.; Nasim, I. Antimicrobial Effect of Ferula Asafoetida against Escherichia Coli when Incorporated in Commercially Available Intracanal Medicament-Calcium Hydroxide: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Pharm. Res. (09752366) 2020, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boghrati, Z.; Iranshahi, M. Ferula species: A rich source of antimicrobial compounds. J. Herb. Med. 2019, 16, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Parmar, R.S. Antimicrobial Activity of Resin of Asafoetida (Hing) against Certain Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Adv. Bioresearch 2018, 19, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi, M.; Abbasi, M.; Safari, Y.; Amiri, R.; Yoosefpour, N. Data set on the antibacterial effects of the hydro-alcoholic extract of Ferula assafoetida plant on Listeria monocytogenes. Data Brief. 2018, 20, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashyal, S.; Rai, S.; Abdul, O. Invitro analysis of phytochemicals and investigation of antimicrobial activity using crude extracts of Ferula assa-foetida stems. METHODS 2017, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Amalraj, A.; Gopi, S. Biological activities and medicinal properties of Asafoetida: A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Ranganathan, M.; Rathinavel, T.; Alagarsamy, P. Characterization of Asafoetida Resin Silver Nanoparticles and Efficacy of Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Inhibition. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotechnol. (IJPSN) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.D.; Shinde, S.; Kandpile, P.; Jain, A.S. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of ASAFOETIDA. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-G.; Hah, D.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.-S. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of the Methanol Extracts from 8 Traditional Medicinal Plants. Toxicol. Res. 2011, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Franier, B.; Jankowski, A.; Thompson, M. Functionalizable self-assembled trichlorosilyl-based monolayer for application in biosensor technology. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 414, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Franier, B.; Asker, D.; van den Berg, D.; Hatton, B.; Thompson, M. Reduction of microbial adhesion on polyurethane by a sub-nanometer covalently-attached surface modifier. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B. The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): Current state and future perspective. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, Z.; Qorbanpour, M.; Rahbar, N. Green synthesis of carbon quantum dots using quince fruit (Cydonia oblonga) powder as carbon precursor: Application in cell imaging and As3+ determination. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 549, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, Z.; Thompson, M. (Eds.) How Functionalization Affects the Detection Ability of Quantum Dots. In Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2023; Volume 22, pp. 37–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mursyalaat, V.; Variani, V.I.; Arsyad, W.O.S.; Firihu, M.Z. The development of program for calculating the band gap energy of semiconductor material based on UV-Vis spectrum using delphi 7.0. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2498, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, Z.; Farrukh, M.A. An efficient nanofiltration system containing mixture of rice husk ash and Fe/CeO2–SiO2 nanocomposite for the removal of azo dye and pesticide. Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Rezaei, A.; Shahlaei, M.; Asani, Z.; Ramazani, A.; Wang, C. Selective and sensitive CQD-based sensing platform for Cu2+ detection in Wilson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Primo, F.L.; Tedesco, A.C.; Bi, H. Copper-Doped Carbon Dots for Optical Bioimaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 13394–13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, A.; Emadi, H.; Nabavi, S.R. Green Synthesis of Sulfur- and Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots for Determination of L-DOPA Using Fluorescence Spectroscopy and a Smartphone-Based Fluorimeter. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 20987–20999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tessmer, I.; Croteau, D.L.; Erie, D.A.; Van Houten, B. Functional characterization and atomic force microscopy of a DNA repair protein conjugated to a quantum dot. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Singh, M.; Kim, S.J.; Schaefer, J. Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan tertiary structure from carbon-13 spin diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7023–7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, S.; Chodisetti Pavan, K.; Reddy, M. Peptidoglycan: Structure, Synthesis, and Regulation. EcoSal Plus 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautner, B.W.; Darouiche, R.O. Role of biofilm in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Am. J. Infect. Control 2004, 32, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, D.; Ghosh, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Acharya, Y.; Mukherjee, R.; Haldar, J. Antimicrobial nanocomposite coatings for rapid intervention against catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 11109–11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, D.-S.; Lee, H.; Park, Y.; Chae, M.; Kim, Y.-C.; Lim, B.; Kang, M.-H.; Ok, M.-R.; Jung, H.-D.; Park, J.-H. Dual-Layer Nanoengineered Urinary Catheters for Enhanced Antimicrobial Efficacy and Reduced Cytotoxicity. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2401700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tailly, T.; MacPhee, R.A.; Cadieux, P.; Burton, J.P.; Dalsin, J.; Wattengel, C.; Koepsel, J.; Razvi, H. Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol-Based Antimicrobial Coatings on Urinary Catheters in the Prevention of Escherichia coli Infections in a Rabbit Model. J. Endourol. 2021, 35, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, M.; Vykydalová, A.; Švajdlenková, H.; Kroneková, Z.; Marković, Z.M.; Kováčová, M.; Špitálský, Z. Antibacterial activity of 3D printed thermoplastic elastomers doped with carbon quantum dots for biomedical applications. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 13009–13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramezani, Z.; Khayat, A.; De La Franier, B.; Ameri, A.; Thompson, M. Green Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Asafoetida and Their Antibacterial Properties. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231804

Ramezani Z, Khayat A, De La Franier B, Ameri A, Thompson M. Green Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Asafoetida and Their Antibacterial Properties. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231804

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamezani, Zahra, Armita Khayat, Brian De La Franier, Abdolghani Ameri, and Michael Thompson. 2025. "Green Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Asafoetida and Their Antibacterial Properties" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231804

APA StyleRamezani, Z., Khayat, A., De La Franier, B., Ameri, A., & Thompson, M. (2025). Green Synthesis of Highly Luminescent Carbon Quantum Dots from Asafoetida and Their Antibacterial Properties. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1804. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231804