Designing 2D Wide Bandgap Semiconductor B12X2H6 (X=O, S) Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

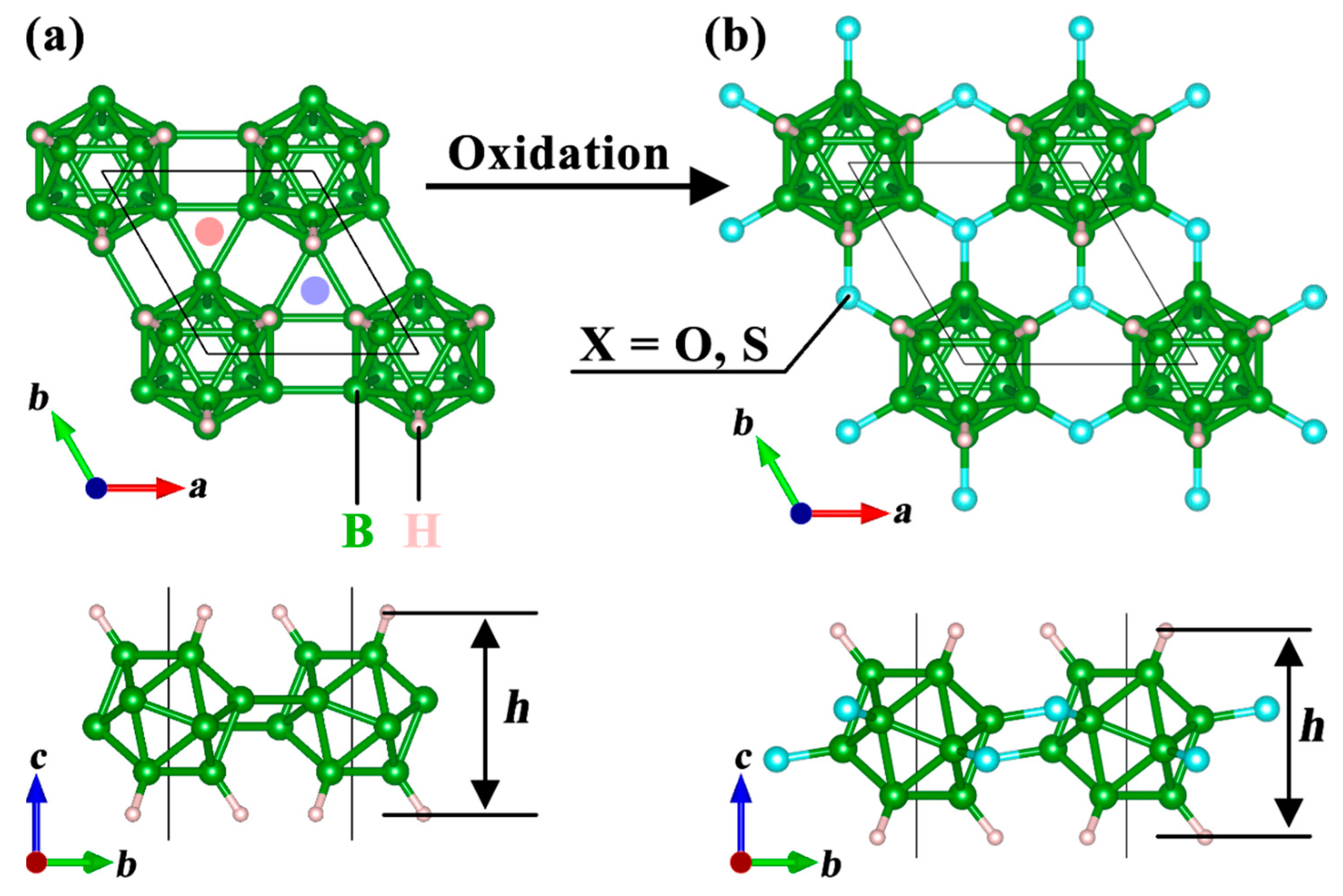

3.1. Structure and Stability

3.2. Electronic Properties

3.3. Alkali Ions Migration

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tai, G.; Hu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Kong, J.; Zeng, T.; You, Y.; Wang, Q. Synthesis of Atomically Thin Boron Films on Copper Foils. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 127, 15693–15697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, A.J.; Zhou, X.-F.; Kiraly, B.; Wood, J.D.; Alducin, D.; Myers, B.D.; Liu, X.; Fisher, B.L.; Santiago, U.; Guest, J.R.; et al. Synthesis of Borophenes: Anisotropic, Two-Dimensional Boron Polymorphs. Science 2015, 350, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannix, A.J.; Zhang, Z.; Guisinger, N.P.; Yakobson, B.I.; Hersam, M.C. Borophene as a Prototype for Synthetic 2D Materials Development. Nature Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Yu, N.; Xue, K.; Miao, X. Ideal Strength and Elastic Instability in Single-Layer 8-Pmmn Borophene. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 8654–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Dai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhuo, Z.; Yang, J.; Zeng, X.C. Two-Dimensional Boron Monolayer Sheets. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7443–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-F.; Dong, X.; Oganov, A.R.; Zhu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.-T. Semimetallic Two-Dimensional Boron Allotrope with Massless Dirac Fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 085502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-L.; Chen, X.; Jian, T.; Chen, T.-T.; Li, J.; Wang, L.-S. From Planar Boron Clusters to Borophenes and Metalloborophenes. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Q.; Lü, T.-Y.; Wang, H.-Q.; Feng, Y.P.; Zheng, J.-C. Review of Borophene and Its Potential Applications. Front. Phys. 2019, 14, 33403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Park, Y.; Qiu, L.; Mitchell, I.; Ding, F. Borophene with Large Holes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 6235–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Tao, W.; Ji, X.; Mei, L. The Emergence and Evolution of Borophene. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2001801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lv, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhuo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, B.; Cheng, P.; et al. Synthesis of Bilayer Borophene. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, N.R.; Marichy, C.; Journet, C.; Bousige, C. Borophene Bottom-up Syntheses: A Critical Review. 2D Mater. 2025, 12, 022005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaev, I.B.; Bregadze, V.I.; Sjöberg, S. Chemistry of Closo-Dodecaborate Anion [B12H12]2−: A Review. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2002, 67, 679–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, A.C.; Khanna, S.N.; Castleman, A.W. Superatom Compounds, Clusters, and Assemblies: Ultra Alkali Motifs and Architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10189–10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleman, A.W.; Khanna, S.N. Clusters, Superatoms, and Building Blocks of New Materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 2664–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Luo, Z. Thirteen-Atom Metal Clusters for Genetic Materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 400, 213053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oganov, A.R.; Chen, J.; Gatti, C.; Ma, Y.; Ma, Y.; Glass, C.W.; Liu, Z.; Yu, T.; Kurakevych, O.O.; Solozhenko, V.L. Ionic High-Pressure Form of Elemental Boron. Nature 2009, 457, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, B.; Hillebrecht, H. Boron: Elementary Challenge for Experimenters and Theoreticians. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8640–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.-Q.; Wei, Y.-F.; Chen, Q.; Mu, Y.-W.; Li, S.-D. Superatom-Assembled Boranes, Carboranes, and Low-Dimensional Boron Nanomaterials Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12 and C2B10. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 6734–6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of Ab-Initio Total Energy Calculations for Metals and Semiconductors Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient Iterative Schemes for Ab Initio Total-Energy Calculations Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.-H.; Yuan, J.-H.; Fonseca, L.R.C.; Miao, X.-S. Improved LDA-1/2 Method for Band Structure Calculations in Covalent Semiconductors. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 153, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.-H.; Chen, Q.; Fonseca, L.R.C.; Xu, M.; Xue, K.-H.; Miao, X.-S. GGA-1/2 Self-Energy Correction for Accurate Band Structure Calculations: The Case of Resistive Switching Oxides. J. Phys. Commun. 2018, 2, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukau, A.V.; Vydrov, O.A.; Izmaylov, A.F.; Scuseria, G.E. Influence of the Exchange Screening Parameter on the Performance of Screened Hybrid Functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 224106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, C.; Kakanakova-Georgieva, A.; Gueorguiev, G.K. A Perspective on Thermal Stability and Mechanical Properties of 2D Indium Bismide from Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 335706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First Principles Phonon Calculations in Materials Science. Scripta Mater. 2015, 108, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.-C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A User-Friendly Interface Facilitating High-Throughput Computing and Analysis Using VASP Code. Computer Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA3 for Three-Dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Huang, K. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-19-267008-3. [Google Scholar]

- Doud, E.A.; Voevodin, A.; Hochuli, T.J.; Champsaur, A.M.; Nuckolls, C.; Roy, X. Superatoms in Materials Science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ming, P.; Li, J. Ab Initio Calculation of Ideal Strength and Phonon Instability of Graphene under Tension. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 064120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Ideal Strength and Phonon Instability in Single-Layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 235407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Tompa, G.S.; Dong, H.; Jian, G.; He, Q.; Tan, P.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Metal–Semiconductor–Metal ε-Ga2O3 Solar-Blind Photodetectors with a Record-High Responsivity Rejection Ratio and Their Gain Mechanism. ACS Photonics 2020, 7, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, Z.; Wu, F.; Dong, D.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Xue, K.; Miao, X.; et al. Ultra-High Performance Amorphous Ga2O3 Photodetector Arrays for Solar-Blind Imaging. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Shockley, W. Deformation Potentials and Mobilities in Non-Polar Crystals. Phys. Rev. 1950, 80, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z. Mobility Anisotropy of Two-Dimensional Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 235306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Kong, X.; Hu, Z.-X.; Yang, F.; Ji, W. High-Mobility Transport Anisotropy and Linear Dichroism in Few-Layer Black Phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.-W. Polarity-Reversed Robust Carrier Mobility in Monolayer MoS2 Nanoribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6269–6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkelman, G.; Uberuaga, B.P.; Jónsson, H. A Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Saddle Points and Minimum Energy Paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.-J.; Hou, Z.F.; Wu, L.-M. First-Principles Study of Lithium Adsorption and Diffusion on Graphene with Point Defects. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 21780–21787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Cabrera, C.R.; Chen, Z. Enhanced Li Adsorption and Diffusion on MoS2 Zigzag Nanoribbons by Edge Effects: A Computational Study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, S.A. Borophene as an Extremely High Capacity Electrode Material for Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 15340–15347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Ab Initio Prediction of Two-Dimensional Si3C Enabling High Specific Capacity as an Anode Material for Li/Na/K-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 4274–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhauriyal, P.; Mahata, A.; Pathak, B. Graphene-like Carbon–Nitride Monolayer: A Potential Anode Material for Na- and K-Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yuan, J.-H.; Fang, W.-Y.; Li, G.; Wang, J. Two-Dimensional V-Shaped PdI2: Auxetic Semiconductor with Ultralow Lattice Thermal Conductivity and Ultrafast Alkali Ion Mobility. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 601, 154176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | a/b | lB-H | lB-B | lB-B/X | h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B12H6 | 4.898 | 1.181 | 1.745~1.793 | 2.004 | 4.674 | 1.552 | 2.210 |

| B12O2H6 | 5.409 | 1.189 | 1.764~1.776 | 1.497 | 4.609 | 3.746 | 4.927 |

| B12S2H6 | 5.950 | 1.192 | 1.777~1.797 | 1.894 | 4.604 | 4.196 | 5.257 |

| Materials | C11/C22 | C12 | C66 | Y11/Y22 | v11/v22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B12H6 | 183.09 | 52.34 | 65.38 | 168.13 | 0.286 |

| B12O2H6 | 219.41 | 51.23 | 84.09 | 207.45 | 0.234 |

| B12S2H6 | 136.51 | 29.08 | 53.71 | 130.31 | 0.213 |

| Materials | Carrier Type | x-Axis | y-Axis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ma* | C2D | μx | mb* | C2D | μy | ||||

| B12O2H6 | h | 11.05 | 2.51 | 190.92 | 20.71 /44.40 | 0.72 | 0.10 | 188.63 | 197,818.31 /1469.41 |

| e | 0.58 | 3.11 | 190.92 | 672.99/ 810.54 | 2.00 | 2.34 | 188.63 | 340.61 /269.75 | |

| B12S2H6 | h | 1.99 | 3.45 | 127.16 | 49.24/ 57.49 | 1.55 | 2.71 | 123.97 | 57.12 /47.29 |

| e | 1.51 | 2.18 | 127.16 | 452.82 /258.41 | 0.46 | 3.94 | 123.97 | 443.64 /635.46 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, P.; Yuan, J.-H.; Wu, G.-P.; Liu, Z.-H.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Designing 2D Wide Bandgap Semiconductor B12X2H6 (X=O, S) Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231803

Gong P, Yuan J-H, Wu G-P, Liu Z-H, Wang H, Wang J. Designing 2D Wide Bandgap Semiconductor B12X2H6 (X=O, S) Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231803

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Pei, Jun-Hui Yuan, Gen-Ping Wu, Zhi-Hong Liu, Hao Wang, and Jiafu Wang. 2025. "Designing 2D Wide Bandgap Semiconductor B12X2H6 (X=O, S) Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231803

APA StyleGong, P., Yuan, J.-H., Wu, G.-P., Liu, Z.-H., Wang, H., & Wang, J. (2025). Designing 2D Wide Bandgap Semiconductor B12X2H6 (X=O, S) Based on Aromatic Icosahedral B12. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231803