Design and Optimization of Self-Powered Photodetector Using Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Ba3SbI3: Insights from DFT and SCAPS-1D

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DFT Simulation

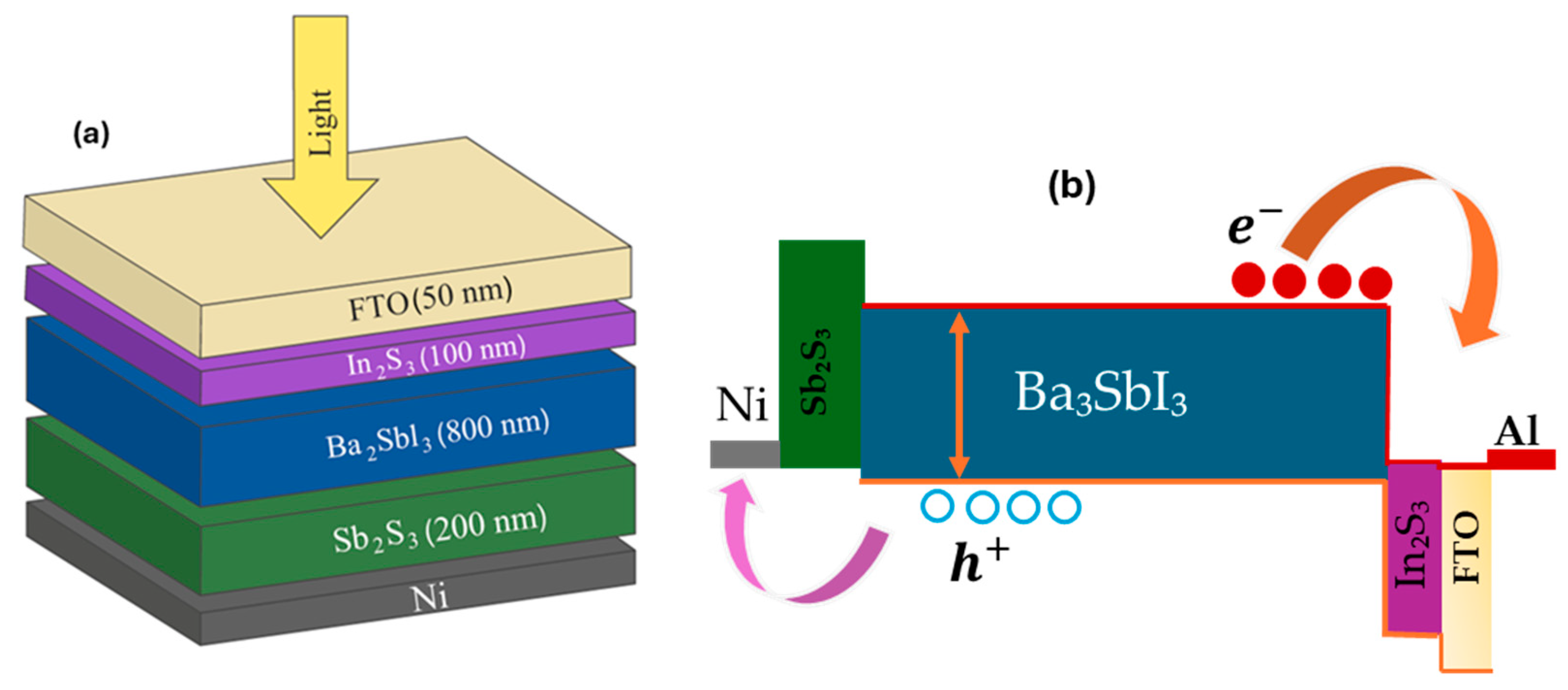

2.2. Simulation and Proposed Design

3. Results

3.1. DFT Calculations

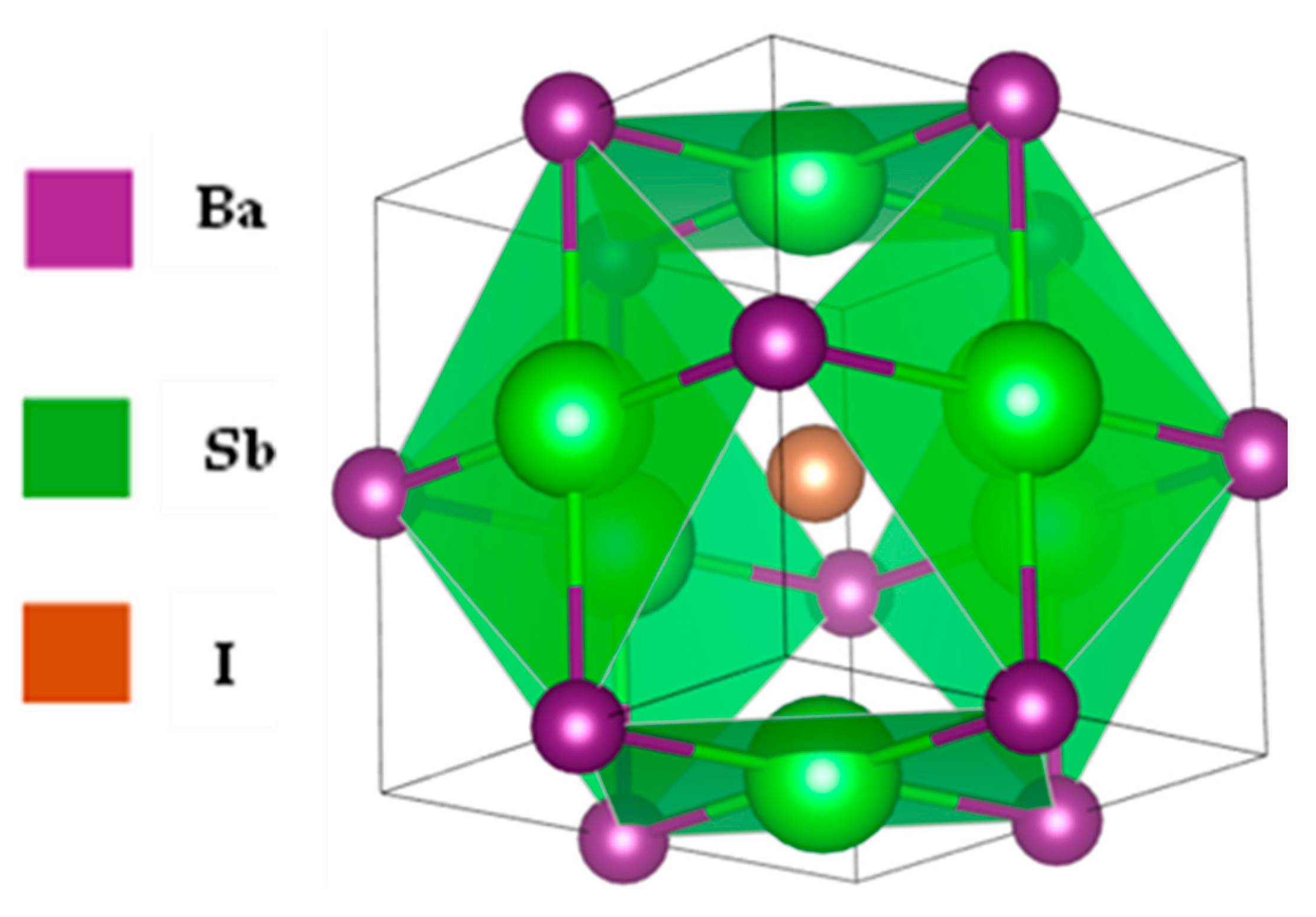

3.1.1. The Structural Properties of the Ba3SbI3 Compound

3.1.2. The Elastic and Mechanical Properties of the Ba3Sbl3 Compound

3.1.3. Electronic, DOS, and Phonon Dispersion Characteristics of Ba3Sbl3 Compound

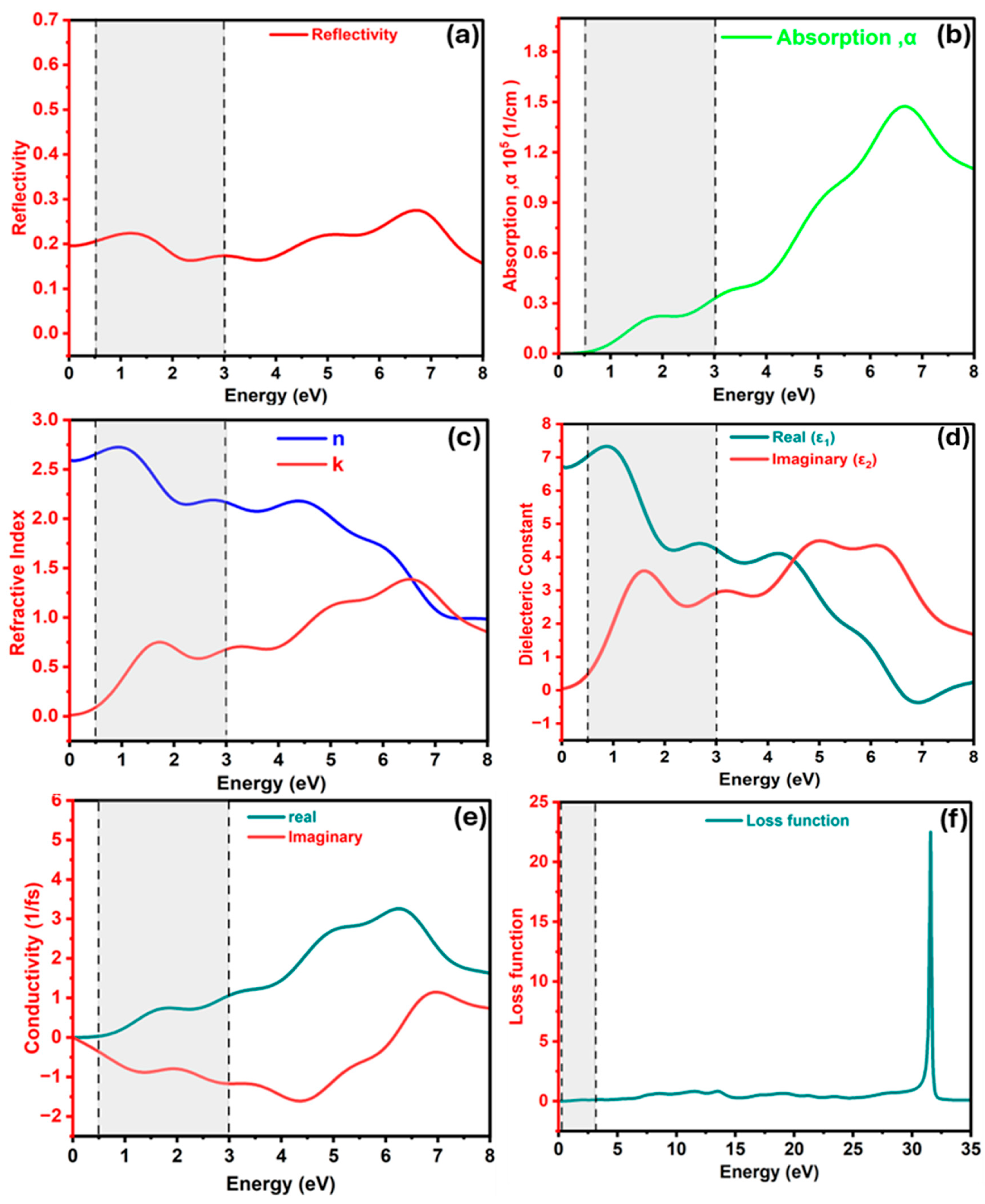

3.1.4. The Optical Properties of the Ba3SbI3 Compound

3.2. Photoresponse of the Ba3Sbl3 Compound

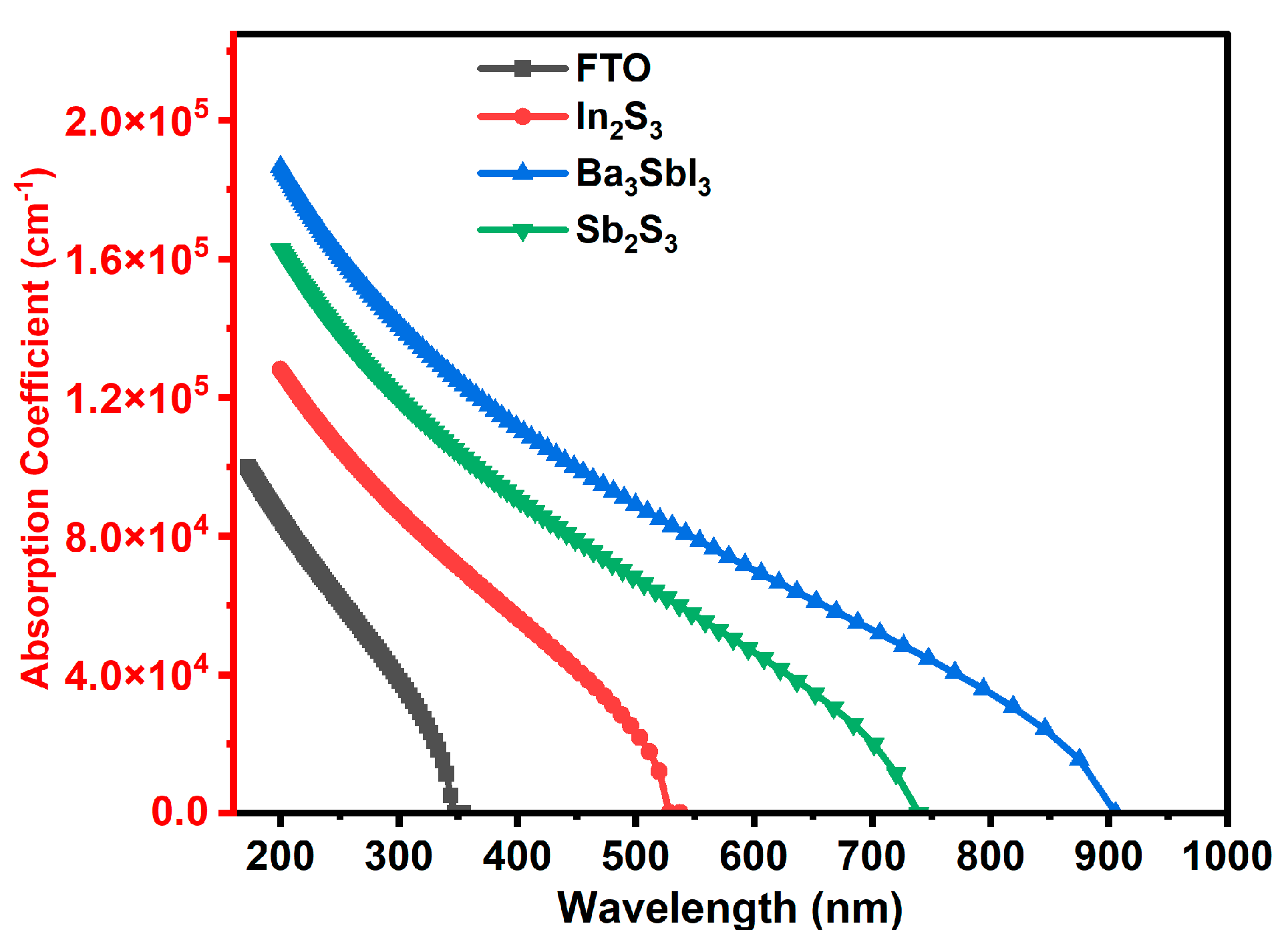

3.2.1. The Absorption Coefficient for All Layers of the Device

3.2.2. The Ba3Sbl3-Based PD with and Without the Sb2S3 Layer

3.2.3. The Influence of Ba3SbI3 (Absorber) Layer Width on the Photodetector

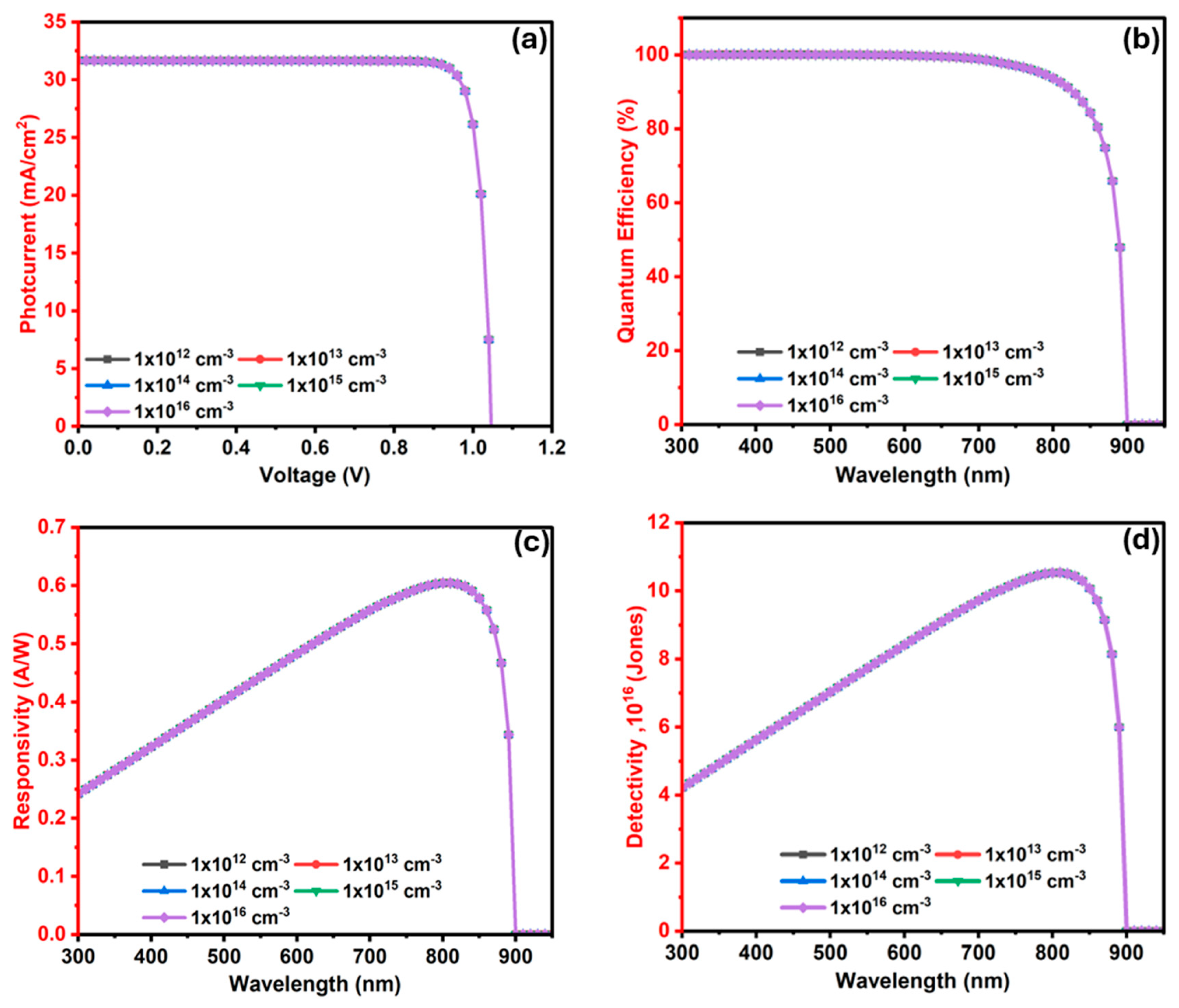

3.2.4. The Influence of Ba3SbI3 (Absorber) Layer Doping Level (NA) on the Photodetector Performance

3.2.5. The Influence of Ba3SbI3 (Absorber) Layer Defects (Nt) on the Photodetector

3.2.6. The Influence of In2S3 (ETL/Window) Layer Width on the Ba3SbI3 Photodetector

3.2.7. The Influence of In2S3 (ETL/Window) Layer Donor Level (ND) on the Ba3SbI3 Photodetector

3.2.8. The Influence of In2S3 (ETL/Window) Layer Defects (Nt) on the Ba3SbI3 Photodetector

3.3. Effect of Working Temperature on Photodetector Performance

3.3.1. Optimized Device Properties

3.3.2. Performance Comparison

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ba3SbI3 | barium antimony iodide |

| CBM | conduction-band minimum |

| EC/EV | energy level of the conduction/valence band |

| ETL/HTL | electron/hole transport layer |

| Eg | bandgap |

| FTO | fluorine-doped tin oxide |

| InGaAs | indium gallium arsenide |

| In2S3 | indium disulfide |

| JSC | short-circuit current density |

| J–V | current voltage |

| MAPbI3 | methylammonium lead iodide |

| NA | acceptor density |

| Nt | defect density |

| PDs | photodetectors |

| QE | quantum efficiency |

| Rs | series resistance |

| Rsh | shunt resistance |

| Sb2S3 | antimony disulfide |

| SCAPS-1D | solar cell capacitance simulator one-dimension |

| SiC | silicon carbide |

| VBM | valence-band maximum |

| VOC | open-circuit voltage |

References

- Gundepudi, K.; Neelamraju, P.M.; Sangaraju, S.; Dalapati, G.K.; Ball, W.B.; Ghosh, S.; Chakrabortty, S. A review on the role of nanotechnology in the development of near-infrared photodetectors: Materials, performance metrics, and potential applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 13889–13924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Irfan, M.; Xu, F.; Wei, Z.; Yang, J.; Kang, L.; Werner, D.H.; et al. Polarization-Sensitive Photodetectors Enabled by Plasmonic Metasurface Integrated Organic Photodiodes. ACS Photonics 2025, 12, 2727–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Chen, M.; Gao, W.; Yang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Dual-electrically configurable MoTe2/In2S3 phototransistor toward multifunctional application. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 27055–27064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Caillas, A.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H.; Shen, X.; Saha, S.; Guyot Sionnest, P. Long-Wave Infrared HgTe Quantum Dot Photoconductors with Optical Enhancement. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 17874–17883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Rohilla, V.; Prakash, K.; Gupta, A.; Ali, T.; Alenezi, A.M.; Islam, M.S.; Soliman, M.S. Design and TCAD analysis of few-layer graphene/ZnO nanowires heterojunction-based photodetector in UV spectral region. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7762. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Nie, C.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Shi, H.; Wei, X. Bionic visual-audio photodetectors with in-sensor perception and preprocessing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Li, C.; Song, J.; He, Y.; Qu, W.; Li, W.; Guo, K.; Liu, L.; Yang, B.; Wei, H. Differential perovskite hemispherical photodetector for intelligent imaging and location tracking. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, J.; Min, C.; Yuan, X.; Somekh, M.; Feng, F. High-performance and stable plasmonic-functionalized formamidinium-based quasi-2D perovskite photodetector for potential application in optical communication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Fu, L. Perovskite photodetector-based single pixel color camera for artificial vision. Light Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, S.; As’ ham, K.; Odebowale, A.A.; Akter, S.; Abdulghani, A.; Al Ani, I.A.; Hattori, H.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. A Near-Ultraviolet Photodetector Based on the TaC: Cu/4 H Silicon Carbide Heterostructure. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Chauhan, R.; Mishra, R.; Srivastava, V. Design and numerical investigation of CsSn0.5Ge0.5I3 perovskite photodetector with optimized performances. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2024, 25, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Guo, C.; Zeng, L.; Ren, X.; Shi, Z.; Wen, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.J.; Shan, C.-X. Phase-controlled van der Waals growth of wafer-scale 2D MoTe2 layers for integrated high-sensitivity broadband infrared photodetection. Light Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Davydova, M.P.; Sukhikh, T.S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Artem’ev, A.V.; Lin, Q. Optoelectronics of Lead-Free Antimony-and Bismuth-Based Metal Halides for Sensitive and Low-Noise Photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, K.; Rafique, S.; Xu, Z.; Niu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Deng, L.; Wang, J.; Yue, X. Highly efficient and stable self-powered mixed tin-lead perovskite photodetector used in remote wearable health monitoring technology. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; Bao, X.; Sun, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y. High-Performance Infrared Self-Powered Photodetector Based on 2D Van der Waals Heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, M.A.H.; Mondal, B.K.; Shiddique, S.N.; Hossain, J. Comprehensive study on the optoelectronic properties of ZnSnP2 compound by DFT and simulation for the application in a photodetector. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 115991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Luo, H.; Zuo, H.; Tao, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, M.; Hu, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, D. Highly sensitive narrowband Si photodetector with peak response at around 1060 nm. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2020, 67, 3211–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikovic, D.; Virot, L.; Aubin, G.; Hartmann, J.-M.; Amar, F.; Le Roux, X.; Alonso-Ramos, C.; Cassan, É.; Marris-Morini, D.; Fédéli, J.-M. Silicon–germanium receivers for short-wave-infrared optoelectronics and communications: High-speed silicon–germanium receivers (invited review). Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, S.; Huang, S.; Wu, Q.; Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, X. Near-Infrared InGaAs Intelligent Spectral Sensor by 3D Heterogeneous Hybrid Integration. Adv. Photonics Res. 2023, 4, 2300043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Sang, Y.; Cui, M.; Li, W.; Yan, Y.; Tao, T.; Xu, W.; Ren, F. Self-powered MXene/GaN van der Waals Schottky ultraviolet photodetectors with exceptional responsivity and stability. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2024, 11, 041413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.K.; Pandey, P.; Yadav, S.; Verma, S.; Sahu, A. Enhancement in Photodetector Sensitivity Using All-Inorganic Perovskite Absorber RbGeI3 and Copper Bismuth Thiocyanate for Superior Charge Transport. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2025, 262, 2400398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, C.; Shen, L.; Ding, L. Lead-free perovskite photodetectors: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetia, A.; Saikia, D.; Sahu, S. Design and optimization of the performance of CsPbI3 based vertical photodetector using SCAPS simulation. Optik 2022, 269, 169804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, S.; Mosconi, E.; Fang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Gao, Y. Stabilizing halide perovskite surfaces for solar cell operation with wide-bandgap lead oxysalts. Science 2019, 365, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maculan, G.; Sheikh, A.D.; Abdelhady, A.L.; Saidaminov, M.I.; Haque, M.A.; Murali, B.; Alarousu, E.; Mohammed, O.F.; Wu, T.; Bakr, O.M. CH3NH3PbCl3 single crystals: Inverse temperature crystallization and visible-blind UV-photodetector. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 3781–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Cho, H.; Heo, J.H.; Kim, T.S.; Myoung, N.; Lee, C.L.; Im, S.H.; Lee, T.W. Multicolored organic/inorganic hybrid perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, X.; Zheng, Y.; Hui, H.; Bian, M.; Dhole, S.; Seo, J.-H.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, S. Chalcogenide perovskite BaZrS3 thin-film electronic and optoelectronic devices by low temperature processing. Nano Energy 2021, 85, 105959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanusch, F.C.; Wiesenmayer, E.; Mankel, E.; Binek, A.; Angloher, P.; Fraunhofer, C.; Giesbrecht, N.; Feckl, J.M.; Jaegermann, W.; Johrendt, D. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells based on formamidinium lead bromide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2791–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulbak, M.; Gupta, S.; Kedem, N.; Levine, I.; Bendikov, T.; Hodes, G.; Cahen, D. Cesium enhances long-term stability of lead bromide perovskite-based solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.-L.; Tan, Q.-H.; Zhu, T.; Yang, P.-Z.; Liu, Y.-P.; Liu, Y.-K.; Wang, Q.-J. High-performance 1D CsPbBr3/CdS photodetectors. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 5932–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Hong, E.; Yan, T.; Fang, X. Effective dual cation release in quasi-2D perovskites for ultrafast UV light-powered imaging. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2412014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Tian, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, L. Stability enhancement of lead-free CsSnI3 perovskite photodetector with reductive ascorbic acid additive. InfoMat 2020, 2, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Sun, H.; Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; He, Y.; Zhu, X. Preparation of bismuth-based perovskite Cs3Bi2I6Br3 single crystal for X-ray detector application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shooshtari, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Pahlavan, S.; Rivera-Sierra, G.; Través, M.J.; Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Bisquert, J.; Linares-Barranco, B. Advancing Logic Circuits With Halide Perovskite Memristors for Next-Generation Digital Systems. SmartMat 2025, 6, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnkar, A.; Gautam, U.K. Challenges and Advances in Low-Temperature Synthesis of Lead-Free BaZrS3 Chalcogenide Perovskite for Optoelectronics. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, e00234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-K.; Ge, C.; Jin, K.-J.; Du, J.-Y.; Yang, J.-T.; Lu, H.-B.; Yang, G.-Z. Self-driven visible-blind photodetector based on ferroelectric perovskite oxides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 142901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.-J.; Zhang, Q. Predicting efficiencies >25% A3MX3 photovoltaic materials and Cu ion implantation modification. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 111902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Ahmed, F.; Ferdous, M.J.; Juhi, M.M.J.; Buian, M.F.I.; Miazee, A.A.; Sajid, M.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Tighezza, A.M.; Ahmmed, M.F. Strain-induced changes in the electronic, optical and mechanical properties of the inorganic cubic halide perovskite Sr3PBr3 with FP-DFT. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 191, 112053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi Talukder, M.; Mehedi Hasan, M.; Al-Humaidi, J.Y.; Quraishi, A.; Rasidul Islam, M.; Masud Rana, M. A DFT and AIMD Study on the Physical and Optoelectronic Properties of Novel A3PF3 (A = Ca, Sr, and Ba) Perovskites for Energy Harvesting Applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Ghosh, A.; Bashar Shanto, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.; Al Ijajul Islam, M.; Rahman, M.H.; Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M. Unraveling the strain-induced and spin–orbit coupling effect of novel inorganic halide perovskites of Ca3AsI3 using DFT. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 085329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, M.A.; Hughes, R.W.; Smith, R.I.; Gregory, D.H. Structural studies of magnesium nitride fluorides by powder neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 185, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadenfeldt, C.; Fester, W. Reindarstellung und thermische Stabilität von Calcium-phosphid-und-arsenidiodiden: Ca3PI3, Ca3AsI3, Ca2PI und Ca2AsI. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1982, 490, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadenfeldt, C.; Schulz, P. Darstellung, Struktur und Temperaturabhängigkeit der Phasenbreite der Phase Ca2−xAs1−xBr1+x und thermisches Verhalten der Verbindung Ca3AsBr3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1984, 518, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadenfeldt, C.; Vollert, H. Darstellung, thermisches Verhalten und Kristallstruktur des Calciumarsenidchlorids Ca3AsCl3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1982, 491, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Toki, M.N.H.; Kuddus, A.; Mohammed, M.K.; Islam, M.R.; Bhattarai, S.; Madan, J.; Pandey, R.; Marzouki, R.; Jemmali, M. Boosting efficiency above 30% of novel inorganic Ba3SbI3 perovskite solar cells with potential ZnS electron transport layer (ETL). Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 300, 117073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Farhat, L.B.; Brahmia, A.; Mohammed, M.K.; Rahman, M.A.; Azzouz-Rached, A.; Rahman, M.F. Analysis of the role of A-cations in lead-free A3SbI3 (A = Ba, Sr, Ca) perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 6365–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Rahman, M.F.; Rahman, M.H.; Bani-Fwaz, M.Z.; Pandey, R.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M. Unlocking the lead-free new all inorganic cubic halide perovskites of Ba3MI3 (M = P, As, Sb) with efficiency above 29%. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 22109–22131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ruan, H.; Sa, R. Comprehensive evaluation of mechanical properties, optoelectronic features, photovoltaic performance, and crystal stability of Ba3MX3 (M = As, Sb; X = Cl, Br, I). Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 186, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Tang, T.-Y.; Liang, Q.-Q.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.-L. A DFT study on novel bismuth-based perovskites. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 190, 113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Toki, M.N.H.; Irfan, A.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Rahaman, R.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Hasan, M.Z. A novel investigation of pressure-induced semiconducting to metallic transition of lead free novel Ba3SbI3 perovskite with exceptional optoelectronic properties. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 11169–11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdo, S.; Odebowale, A.A.; Abdulghani, A.; As’ ham, K.; Akter, S.; Hattori, H.; Kanizaj, N.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Unveiling the Potential of Novel Ternary Chalcogenide SrHfSe3 for Eco-Friendly, Self-Powered, Near-Infrared Photodetectors: A SCAPS-1D Simulation Study. Sci 2025, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, M.A.H.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Hossain, J. Design and simulation of BeSiP2-based high-performance solar cell and photosensor. Sol. Energy 2024, 279, 112837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Kumar, B.; Dwivedi, D. Numerical simulation of non-toxic In2S3/SnS2 buffer layer to enhance CZTS solar cells efficiency by optimizing device parameters. Optik 2021, 227, 166087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.C.; Mondal, B.K.; Pappu, M.A.H.; Hossain, J. Numerical evaluation and optimization of high sensitivity Cu2CdSnSe4 photodetector. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossen, M.S.; Abir, A.T.; Hossain, J. Design of an efficient AgInSe2 chalcopyrite-based heterojunction thin-film solar cell. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Lei, Z.; Huang, B.; Wei, A.; Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y. Non-Layered Te/In2S3 tunneling heterojunctions with ultrahigh photoresponsivity and fast photoresponse. Small 2022, 18, 2200445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Alam, I. Numerical simulation of CIGS, CISSe and CZTS-based solar cells with In2S3 as buffer layer and Au as back contact using SCAPS 1D. Eng. Res. Express 2020, 2, 035015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyad, M.N.H.; Sunny, A.; Khatun, M.M.; Rahman, S.; Ahmed, S.R.A. Performance evaluation of WS2 as buffer and Sb2S3 as hole transport layer in CZTS solar cell by numerical simulation. Eng. Rep. 2023, 5, e12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, J.; Shi, S.; Kong, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, L. Self-Powered Ultraviolet–Visible-Near infrared broad spectrum Sb2S3/TiO2 photodetectors and The application in emotion detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 161890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Chowdhury, M.; Marasamy, L.; Mohammed, M.K.; Haque, M.D.; Al Ahmed, S.R.; Irfan, A.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Goumri-Said, S. Improving the efficiency of a CIGS solar cell to above 31% with Sb2S3 as a new BSF: A numerical simulation approach by SCAPS-1D. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 1924–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ranjan, R.; Mishra, V.K.; Srivastava, N.; Tiwari, R.N.; Singh, L.; Sharma, A.K. Boosting the efficiency up to 33% for chalcogenide tin mono-sulfide-based heterojunction solar cell using SCAPS simulation technique. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.S.; Shaker, A.; Aledaily, A.N.; Alanazi, A.; Al-Dhlan, K.A.; Okil, M. Comprehensive design and analysis of thin film Sb2S3/CIGS tandem solar cell: TCAD simulation approach. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 075511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Hasan, S.S.; Hasan, M.Z.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Ali, M.M.; Hossain, A.; Khokan, R.M.; Hossain, M.M.; Mukhtar, N.M. Insight into the physical properties of the chalcogenide XZrS3 (X = Ca, Ba) perovskites: A first-principles computation. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 3775–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Toki, M.N.H.; Islam, M.R.; Barman, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Rasheduzzaman, M.; Hasan, M.Z. A computational study of electronic, optical, and mechanical properties of novel Ba3SbI3 perovskite using DFT. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudian Saadabad, R.; Pauly, C.; Herschbach, N.; Neshev, D.N.; Hattori, H.T.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Highly efficient near-infrared detector based on optically resonant dielectric nanodisks. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Deng, L. Enhanced photoelectric responsivity of graphene/GaAs photodetector using surface plasmon resonance based on ellipse wall grating-nanowire structure. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, M.; Decock, K.; Niemegeers, A.; Verschraegen, J.; Degrave, S. SCAPS Manual; University of Ghent: Ghent, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ait Abdelkadir, A.; Oublal, E.; Sahal, M.; Gibaud, A. Numerical simulation and optimization of n-Al-ZnO/n-CdS/p-CZTSe/p-NiO (HTL)/Mo solar cell system using SCAPS-1D. Results Opt. 2022, 8, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.; Srivastava, A.; Sinha, R.; Roy, N. Design and optimization of high-performance MoSe2/PC60BM heterostructure based self-powered photodetector. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 314, 118018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, S.; Christopoulos, S.; Abu Waar, Z.; Moustafa, M. Numerical Modeling and Optimization of High-Performance CsSnI3 Perovskite Photodetectors. J. Electron. Mater. 2025, 54, 5690–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.S.; Ramalan, A.M.; Abubakar, A.A.; Mohammed, I.K. Effect of Electron Transport Layers, Interface Defect Density and Working Temperature on Perovskite Solar Cells Using SCAPS 1-D Software. East Eur. J. Phys. 2024, 1, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenfack, A.D.K.; Thantsha, N.M.; Msimanga, M. Simulation of lead-free heterojunction CsGeI2Br/CsGeI3-based perovskite solar cell using SCAPS-1D. Solar 2023, 3, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.; Rasu Chettiar, A.-D.; Vincent Mercy, E.N.; Marasamy, L. Scrutinizing the untapped potential of emerging ABSe3 (A = Ca, Ba; B = Zr, Hf) chalcogenide perovskites solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebon, M.I.R.; Pappu, M.A.H.; Shiddique, S.N.; Hossain, J. Unveiling the potentiality of a self-powered CGT chalcopyrite-based photodetector: Theoretical insights. Opt. Mater. Express 2024, 14, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika, S.; Mahalakshmi, M.; Pandian, M.S. TiO2/CdS/CdSe quantum dots co-sensitized solar cell with the staggered-gap (type-II) heterojunctions for the enhanced photovoltaic performance. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 8820–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiddique, S.N.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Pappu, M.A.H.; Islam, M.C.; Hossain, J. Design and simulation of a high performance Ag3CuS2 jalpaite-based photodetector. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miah, M.R.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Abir, A.T.; Hossain, J. A theoretical analysis to reveal the prospects of MoS2 as a back surface field layer in TiS3-based near infrared photodetector. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 025338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Ria, M.S.I.; Ghosh, A.; Alrafai, H.; Al Baki, A.; Abdelrahim, S.K.A.; Al-Humaidi, J.Y.; Robin, R.I.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Maniruzzaman, M. Investigating the physical characteristics and photovoltaic performance of inorganic Ba3NCl3 perovskite utilizing DFT and SCAPS-1D simulations. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 308, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.F.; Marasamy, L.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Ghosh, A.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Irfan, A. Impact of A-cations modified on the structural, electronic, optical, mechanical, and solar cell performance of inorganic novel A3NCl3 (A = Ba, Sr, and Ca) perovskites. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 8199–8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Huang, K. Dynamical Theory of Crystal Lattices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Rehman, F.; Liaqat, M.; Quraishi, A.; Norberdiyeva, M.; Ullah, A.; Khan, I.; Tirth, V.; Mohammed, R.M.; Algahtani, A. High thermoelectric and opto-electronic properties of Ba3NX3 (X = F, Cl) perovskite: Insights from DFT computation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 225, 112129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Yu, C.-F. A DFT Characterization of Structural, Mechanical, and Thermodynamic Properties of Ag9In4 Binary Intermetallic Compound. Metals 2022, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kube, C.M. Elastic anisotropy of crystals. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 095209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, J.; Leger, J.; Bocquillon, G. Synthesis and design of superhard materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2001, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, S. XCII. Relations between the elastic moduli and the plastic properties of polycrystalline pure metals. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1954, 45, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharber, M.C.; Sariciftci, N.S. Low band gap conjugated semiconducting polymers. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2000857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Dahliah, D.; Hasan, M.R.; Kassa, G.; Pike, A.; Quadir, S.; Claes, R.; Chandler, C.; Xiong, Y.; Kyveryga, V. Discovery of the Zintl-phosphide BaCd2P2 as a long carrier lifetime and stable solar absorber. Joule 2024, 8, 1412–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljameel, A.; Mustafa, G.M.; Younas, B.; Alkhaldi, H.D.; Alhajri, F.; Ameereh, G.; Sfina, N.; Alshomrany, A.S.; Mahmood, Q. Investigation of optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties of novel BaCd2X2 (X = P, As, Sb) Zintl-phase for energy harvesting applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 189, 111953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureddine, E.; Sarkar, B.B.; Rahman, M.A.; Adam, A.M.A.; Rahman, M.H.; Rajabathar, J.; Mohsen, Q.; Alshihri, A.A.; Khan, M.T.; Uddin, M.S. Innovative Computational Framework for Sr3SbCl3 Absorber Optimization: DFT, SCAPS-1D, and Machine Learning Perspectives. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 14529–14552. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, K.K.; Sharma, R. A comparative study of the structural, electronic, and optical properties of Ca3SbCl3 halide perovskite using DFT-GGA and HSE06 functional for photovoltaic applications. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 57, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Min, J.; Dong, T.; Wen, W.; Feng, Z.; Yang, G.; Yan, Y.; Zeng, Z. Flat phonon modes driven ultralow thermal conductivities in Sr3AlSb3 and Ba3AlSb3 Zintl compounds. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 120, 142103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roknuzzaman, M.; Ostrikov, K.; Wang, H.; Du, A.; Tesfamichael, T. Towards lead-free perovskite photovoltaics and optoelectronics by ab-initio simulations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Gamel, M.M.A.; Ker, P.J.; Jamaludin, M.Z.; Wong, Y.H.; David, J.P. Absorption coefficient of bulk III-V semiconductor materials: A review on methods, properties and future prospects. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 51, 6082–6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Celliers, P.M.; Eggert, J.H.; Lazicki, A.; Millot, M. Interferometric measurements of refractive index and dispersion at high pressure. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, H.; Tahir, M.B.; Almutairi, B.S.; Khalid, I.; Sagir, M.; Ali, H.E.; Alrobei, H.; Alzaid, M. CASTEP study for mapping phase stability, and optical parameters of halide perovskite CsSiBr3 for photovoltaic and solar cell applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 150, 110474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homes, C.; Vogt, T.; Shapiro, S.; Wakimoto, S.; Ramirez, A. Optical response of high-dielectric-constant perovskite-related oxide. Science 2001, 293, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiddique, S.N.; Mondal, B.K.; Hossain, J. Modeling of Ag3AuS2-based NIR photodetector with BaSi2 BSF layer for superior detectivity. Opt. Contin. 2025, 4, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Lu, G.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Chen, M.; Ma, M.; Li, W.; Yang, C. Towards high sensitivity infrared detector using Cu2CdxZn1-xSnSe4 thin film by SCAPS simulation. Sol. Energy 2021, 225, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebon, M.I.R.; Ali, M.H.; Haque, M.D.; Islam, A.Z.M.T. Computational investigation towards highly efficient Sb2Se3 based solar cell with a thin WSe2 BSF layer. Eng. Res. Express 2023, 5, 045072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiddique, S.N.; Abir, A.T.; Nushin, S.S.; Mondal, B.K.; Hossain, J. Numerical probing into the role of experimentally developed ZnTe window layer in high-performance Ag3AuSe2 photodetector. Results Mater. 2025, 25, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaque, S.K.; Mondal, B.K.; Hossain, J. Numerical simulation on the impurity photovoltaic (IPV) effect in c-Si wafer-based dual-heterojunction solar cell. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Gour, K.S.; Singh, V. Photodetector performance limitations: Recombination or trapping—Power exponent variation with the applied bias to rescue. J. Mater. Res. 2023, 38, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.R.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Abir, A.T.; Hossain, J. Modeling and Numerical Insights of TiSe2 Compound-Based Photodetector. Adv. Theory Simul. 2024, 7, 2400389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Kang, Y.; Cai, M.; Xia, Y.; Deng, H. Design and optimization of the performance of self-powered Sb2S3 photodetector by SCAPS-1D simulation and potential application in imaging. Opt. Mater. 2024, 147, 114594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guo, S.; Zhao, X.; Quan, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, R.; Weller, D. Modeling and simulation of MAPbI3-based solar cells with SnS2 as the electron transport layer (ETL) and MoS2 as the hole transport layer (HTL). ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 5997–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.A. Efficiency enhancement of WSe2/In2S3 solar cell by numerical modeling using SCAPS. Opt. Contin. 2024, 3, 2377–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.S.; Pappu, M.A.H.; Hossain, J. Theoretical design and insight of Fe2GeS4-based optoelectronic devices. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuddus, A.; Ismail, A.B.M.; Hossain, J. Design of a highly efficient CdTe-based dual-heterojunction solar cell with 44% predicted efficiency. Sol. Energy 2021, 221, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.R.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Abir, A.T.; Hossain, J. Discovering the inherent properties of CdS/TiTe2/Cu2Te near infrared photodetector: A computational analysis. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouslimane, T.; Et-Taya, L.; Elmaimouni, L.; Benami, A. Impact of absorber layer thickness, defect density, and operating temperature on the performance of MAPbI3 solar cells based on ZnO electron transporting material. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Tao, R.; Cao, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Manipulating the Light-Matter Interaction of PtS/MoS2 p–n Junctions for High Performance Broadband Photodetection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Fan, H.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J.; Cao, F.; Li, L.; Tong, Y.; Wang, H. Embedding of Ti3C2Tx nanocrystals in MAPbI3 microwires for improved responsivity and detectivity of photodetector. Small 2021, 17, 2101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, T.; Ghoshal, D.; Yoshimura, A.; Basu, S.; Chow, P.K.; Lakhnot, A.S.; Pandey, J.; Warrender, J.M.; Efstathiadis, H.; Soni, A. An environmentally stable and lead-free chalcogenide perovskite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Tolani, M.; Kumar, R. Design and simulations of Ge2Sb2Te5 vertical photodetector for silicon photonic platform. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 18, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, Q.; Gao, C. Performance engineering of eco-friendly Mg2Si/Si photodetectors: TCAD-validated advantages of PIN over PN structures for visible-NIR detection. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 075112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N. Design and performance evaluation of MoS2 photodetector in vertical MSM configuration. Opt. Mater. 2024, 148, 114817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.C.; Pappu, M.A.H.; Ahmed, T.; Hossain, J. Theoretical Sagacity of an Efficient Cu2ZnGeSe4-Based Thin Film Solar Cell and Photodetector. Adv. Theory Simul. 2025, 8, e01272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Liu, L. Design and optimize the performance of self-powered photodetector based on PbS/TiS3 heterostructure by SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Dey, N.L.; Hasan, M.R.; Bappy, M.A.; Kabir, M.H.; Begum, S.; Ahmed, S.; Howlader, A.S.; Awwad, N.S.; Alturaifi, H.A. Innovative double absorber solar cell design combining Ca3AsI3 and Ca3PI3 perovskites for achieving over 29% efficiency. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 183, 112399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalianya, M.A.; Awino, C.; Barasa, H.; Odari, V.; Gaitho, F.; Omogo, B.; Mageto, M. Numerical study of lead free CsSn0.5Ge0.5I3 perovskite solar cell by SCAPS-1D. Optik 2021, 248, 168060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.R.A. Investigation on the performance enhancement of heterojunction SnS thin-film solar cell with a Zn3P2 hole transport layer and a TiO2 electron transport layer. Energy Fuels 2023, 38, 1462–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horani, F.; Lifshitz, E. Deciphering the Structural Evolution and Growth Mechanism of 3D β-In2S3 Nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 30723–30731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhu, Y. Correlation effects on lattice relaxation and electronic structure of ZnO within the GGA+ U formalism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 26029–26039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzwan, A.; Ahmed, R.; Shaari, A.; Lawal, A.; Ng, Y.X. First-principles calculations of antimony sulphide Sb2S3. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2017, 13, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, M.H.; Roslan, M.S.B.; Mayzan, M.Z.H.B.; Shaaban, I.A.; Rizvi, S.Z.H.; Agam, M.A.B.; Saleem, S.; Assiri, M.A. A comparative DFT study of bandgap engineering and tuning of structural, electronic, and optical properties of 2D WS2, PtS2, and MoS2 between WSe2, PtSe2, and MoSe2 materials for photocatalytic and solar cell applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 34, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadeja, P.; Yadav, S.; Ravalia, A.; Katba, S. Investigating the impact of various Electron Transport Layers on the performance of Sn-based Perovskite Solar Cells: A Device Simulation using SCAPS-1D. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 208, 113088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.N.; Ebon, M.I.R.; Hossain, J. Numerical Simulation to Achieve High Efficiency in CuTlSe2–Based Photosensor and Solar Cell. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025, 4967875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebon, M.I.R.; Abir, A.T.; Pathak, D.; Hossain, J. Theoretical insights toward a highly responsive AgInSe2 photodetector. Appl. Res. 2024, 3, e202400038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, S.; Deo, M.; Chauhan, R. Unveiling the potential of organometal halide perovskite materials in enhancing photodetector performance. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2023, 55, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanta, S.; Nayak, C.; Agarwal, P.; Das, K.; Singha, A. Monolayer Graphene–MoSSe van der Waals Heterostructure for Highly Responsive Gate-Tunable Near-Infrared-Sensitive Broadband Fast Photodetector. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 14523–14531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, S.; Qian, W.; Zhang, K.; Yu, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, G.; Zheng, S.; Yang, S. Self-driven perovskite narrowband photodetectors with tunable spectral responses. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, H.; Dong, R.; Venanzi, T.; Zscharschuch, J.; Schneider, H.; Helm, M.; Feng, X.; Cánovas, E.; Erbe, A. Demonstration of a broadband photodetector based on a two-dimensional metal–organic framework. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lattice Constant a(Å) | Optimum Volume (Å3) | Final Enthalpy | Density (Amu Å−3) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.05 | 350.4026 | 3199.64855 | 2.609 | This work |

| 7.05 | 350.403 | −3199.64 | - | [64] |

| 7.055 | 351.133 | - | - | [49] |

| 7.07 | 2387.1922 | - | - | [46] |

| 7.08 | - | - | - | [47] |

| 7.04 | 350.091 | −3199.65 | 2.612 | [50] |

| 7.05 | 330 | - | - | [48] |

| Parameter | rA | rsb | rX | Tolerance Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba3SbI3 | 1.42 | 0.71 | 2.2 | 0.865 |

| Parameter | Our Calc. | Other Theo. |

|---|---|---|

| C11 (GPa) | 53.366 | 53.817 a, 54.067 b |

| C12 (GPa) | 6.5767 | 7.0199 a, 7.0366 b |

| C44 (GPa) | 8.6655 | 8.6732 a, 8.6379 b |

| Bulk modulus B (GPa) | 22.17 | 22.62 a, 22.71 b |

| Shear modulus G (GPa) | 13.07 | 13.08 a, 13.07 b |

| Young’s modulus E (GPa) | 32.77 | 32.89 a, 32.91 b |

| Anisotropy factor A | 0.372 | |

| Universal anisotropy factor AU | 1.28 | 1.28 a, 1.31 b |

| Poisson’s ratio v | 0.254 | 0.235 a, 0.258 b |

| Pugh’s ratio B/G | 1.70 | 1.729 a, 1.737 b |

| Compound | Bandgap (eV) | ECut [eV] | k-Point | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba3SbI3 | 0.78 (PBE) 1.602 (HSE) | 500 | 8 × 8 × 8 | This work |

| 1.512 (HSE) | 550 | 10 × 10 × 10 | [49] | |

| 1.4 (HSE) | 550 | 8 × 8 × 8 | [48] | |

| 1.38 (HSE) | - | - | [37] | |

| 0.78 (PBE) 1.38 (HSE) | 500 | 6 × 6 × 6 | [64] | |

| 0.856 (PBE) 1.384 (HSE) | 410 | 6 × 6 × 6 | [47] | |

| 1.056 (PBE) 1.38 (HSE) | - | 6 × 6 × 6 | [46] | |

| 0.78 (PBE) | 400 | 6 × 6 × 6 | [45] |

| Structure | Voc | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Wavelength (nm) | Responsivity (A/W) | Detectivity (Jones) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In2S3/Ba3Sbi33 | 0.9017 | 26.80 | 750 | 0.51 | 5.41 × 1015 |

| In2S3/Ba3Sbi33/Sb2S3 | 1.047 | 31.65 | 810 | 0.605 | 1.05 × 1017 |

| Structure | Types of Work | Software Used /Method | λ (nm) | Responsivity (A/W) | Detectivity (Jones) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS2/PtS | Experiment | E-beam evaporation + CVD | 400 | 25.43 | 8.54 × 1012 | [111] |

| MXene/MAPbI3 | Experiment | Solution processed | 525 | 1.70 | 7.0 × 1011 | [112] |

| BaZrS3 | Experiment | Solution + sulfurization at 1050 °C | 405 | 46.5 × 10−3 | - | [113] |

| TaC:Cu/4H Silicon Carbide | Experiment | Co-sputtering | 405 | 1.66 | 2.69 × 108 | [10] |

| Ge2Sb2Te5 | Simulation | Lumerical charge | 1550 | ~48 | - | [114] |

| Graphene/GaAs | Simulation | COMSOL Multiphysics | 725 | 0.514 | 1.16 × 1011 | [66] |

| p–Mg2Si/i–Mg2Si/n–Si | Simulation | TCAD Silvaco | 400–1500 | 0.45 | 7.42 × 1011 | [115] |

| p-MoS2 | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 700 | 0.37 | 3.27 × 1014 | [116] |

| CdS/p-Cu2ZnGeSe4/ p+-ZnTe | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 780 | 0.58 | 8.28 × 1017 | [117] |

| PbS/TiS3 | Simulation | SCAPD-1D | 780 | 0.36 | 3.9 × 1013 | [118] |

| n-ZnSe/p-TiSe2/p+-WSe2 | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 920 | 0.670 | 12.90 × 1014 | [103] |

| n-In2S3/p-BeSiP2/p+-MoS2 | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 860 | 0.64 | 3.63 × 1016 | [52] |

| n-WS2/p-Ag3CuS2/p+-BaSi2 | Simulation | SCPDS-1D | 1065 | 0.790 | 4.73 × 1014 | [76] |

| ZnSe/p-SrHfSe3/p+-AgCuS | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 1100 | 0.850 | 2.26 × 1014 | [51] |

| n-In2S3/p-Ba3SbI3/p+- Sb2S3 | Simulation | SCAPS-1D | 810 | 0.605 | 1.05 × 1017 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdo, S.; Odebowale, A.A.; Abdulghani, A.; As’ham, K.; Djalab, Y.; Kanizaj, N.; Miroshnichenko, A.E. Design and Optimization of Self-Powered Photodetector Using Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Ba3SbI3: Insights from DFT and SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211656

Abdo S, Odebowale AA, Abdulghani A, As’ham K, Djalab Y, Kanizaj N, Miroshnichenko AE. Design and Optimization of Self-Powered Photodetector Using Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Ba3SbI3: Insights from DFT and SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(21):1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211656

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdo, Salah, Ambali Alade Odebowale, Amer Abdulghani, Khalil As’ham, Yacine Djalab, Nicholas Kanizaj, and Andrey E. Miroshnichenko. 2025. "Design and Optimization of Self-Powered Photodetector Using Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Ba3SbI3: Insights from DFT and SCAPS-1D" Nanomaterials 15, no. 21: 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211656

APA StyleAbdo, S., Odebowale, A. A., Abdulghani, A., As’ham, K., Djalab, Y., Kanizaj, N., & Miroshnichenko, A. E. (2025). Design and Optimization of Self-Powered Photodetector Using Lead-Free Halide Perovskite Ba3SbI3: Insights from DFT and SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials, 15(21), 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211656