Refractive Index Sensing Properties of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface

Abstract

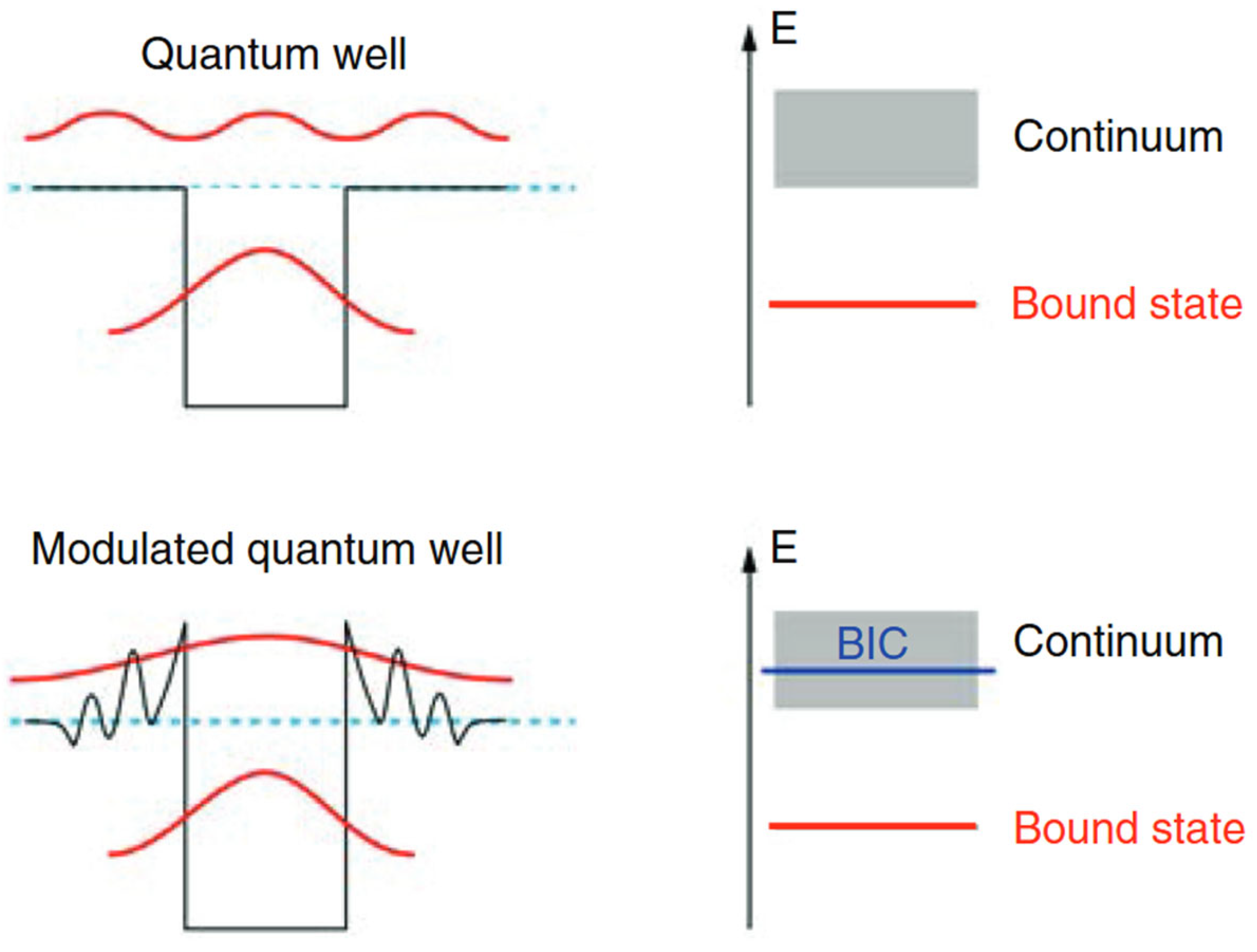

1. Introduction

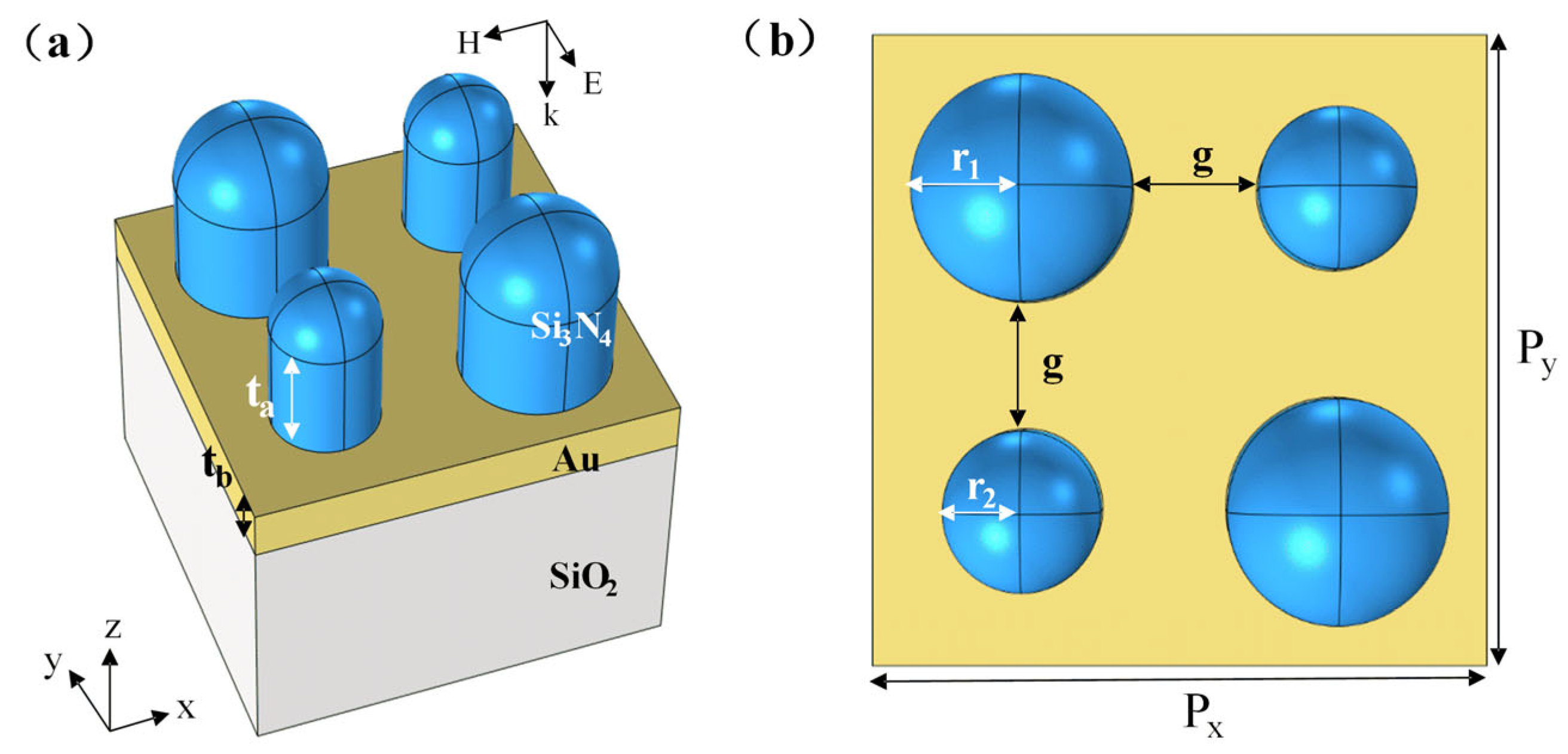

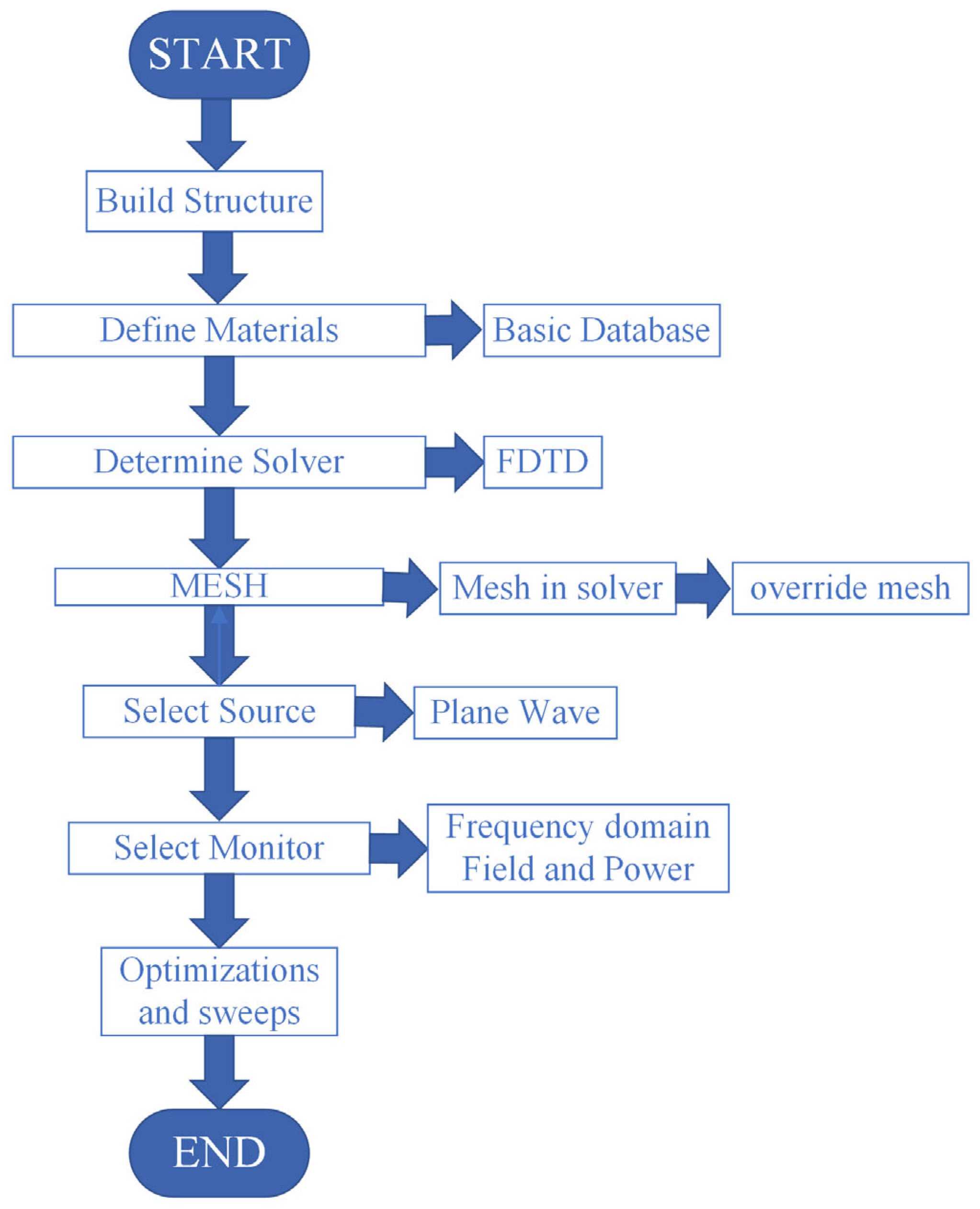

2. Models and Methods

2.1. Model and Modeling

2.2. Surface Plasmon Resonance Theory

2.3. The Key Indicators of Refractive Index Sensing

3. Results and Discussion

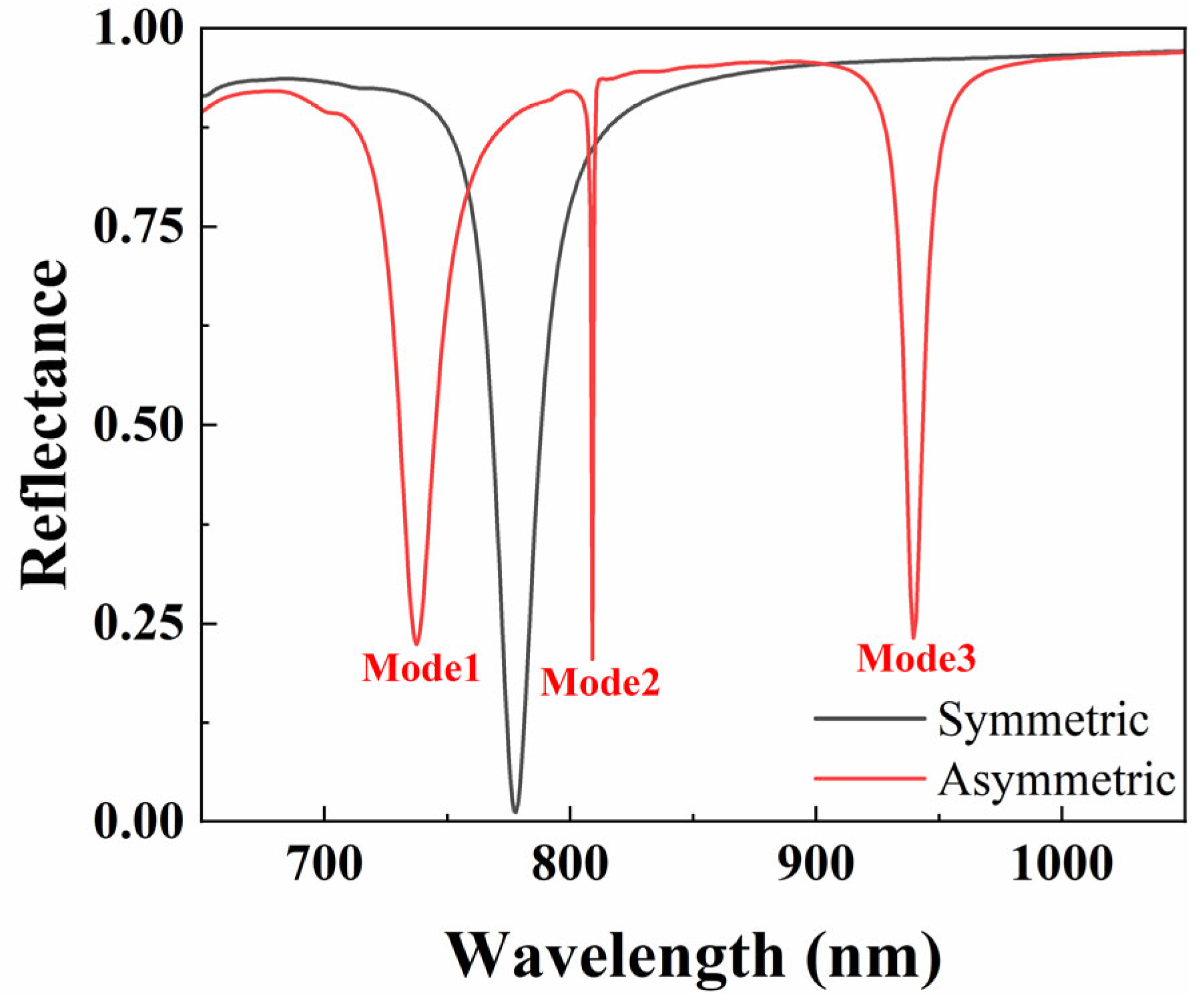

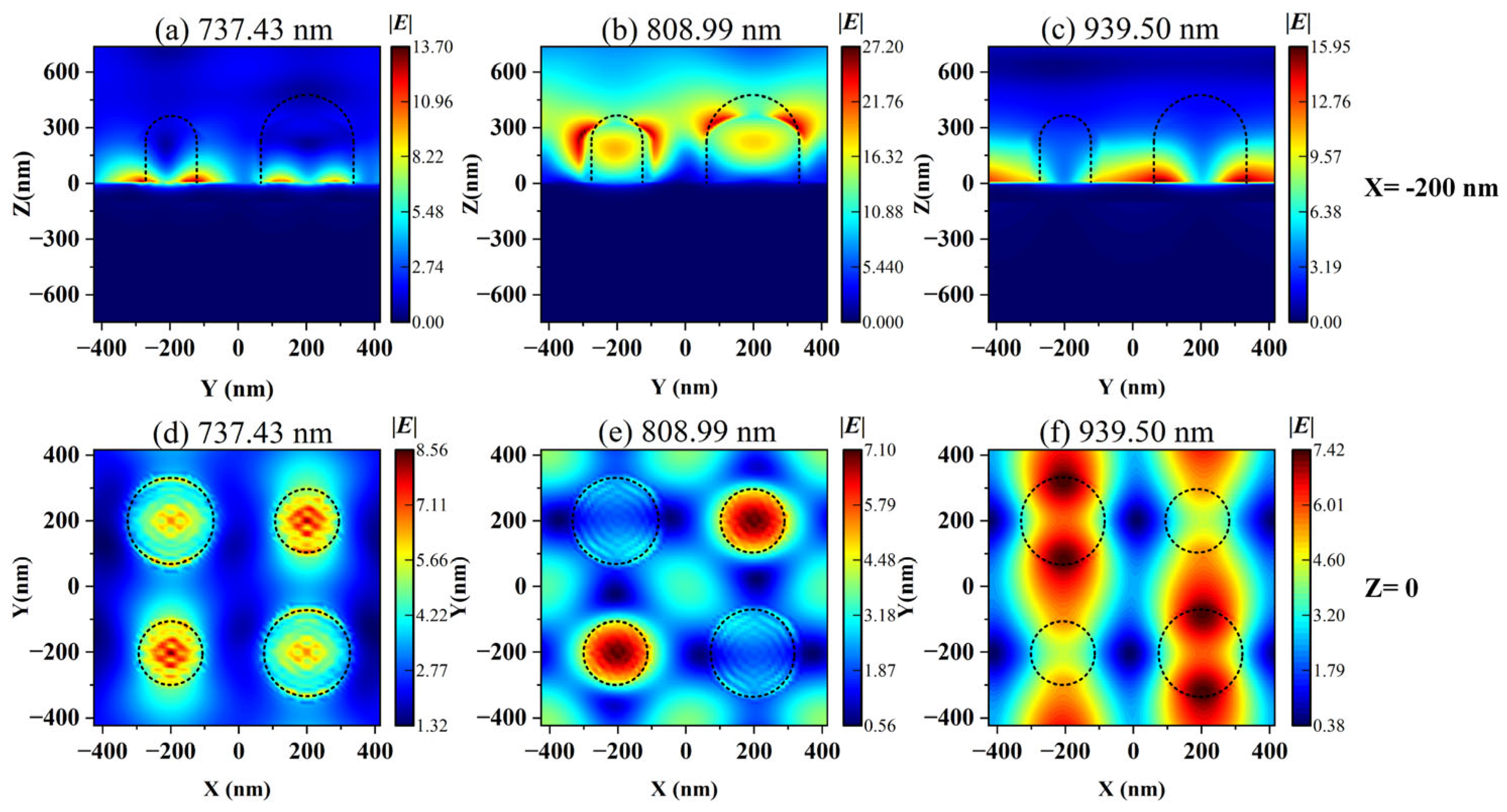

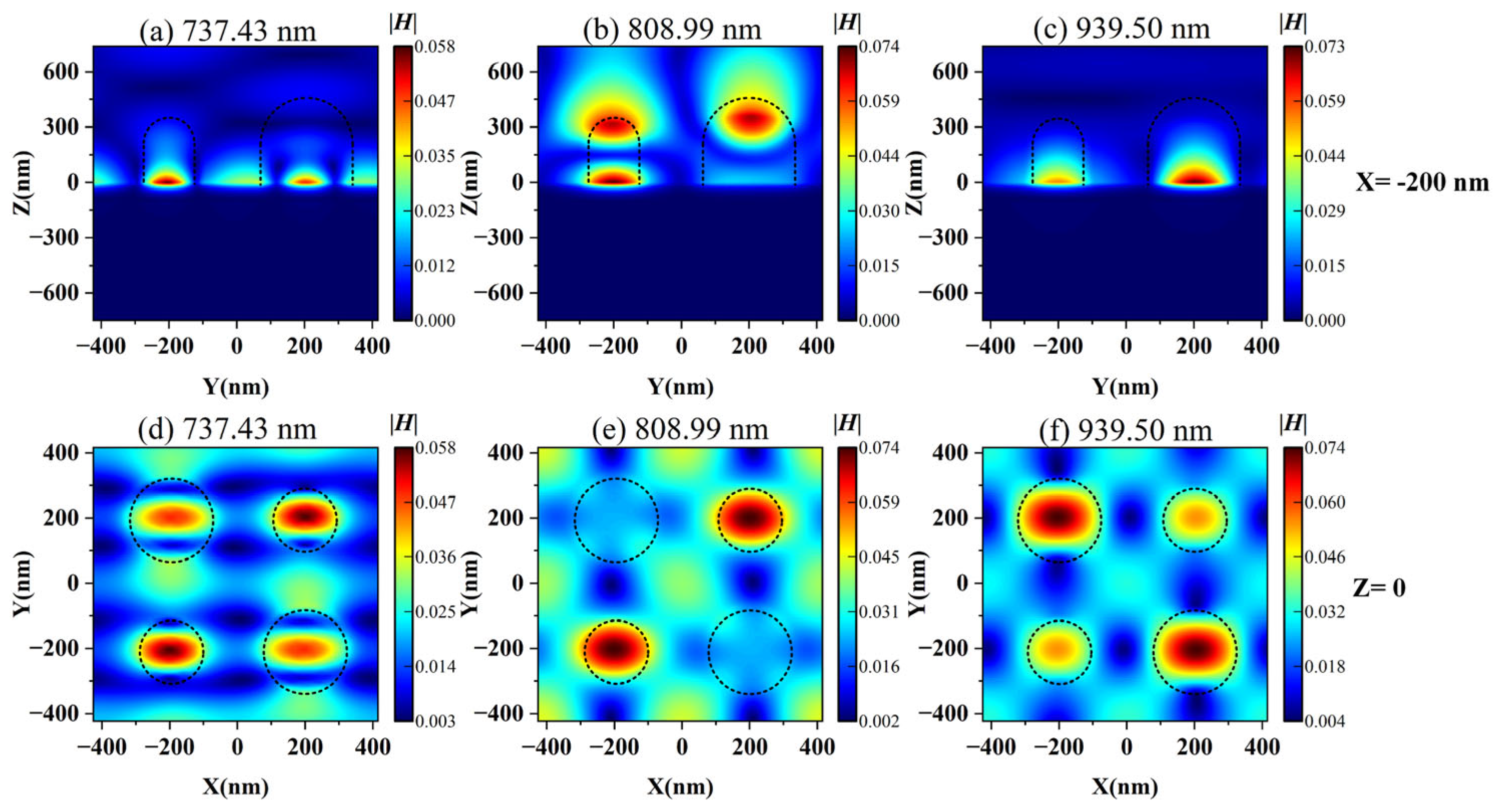

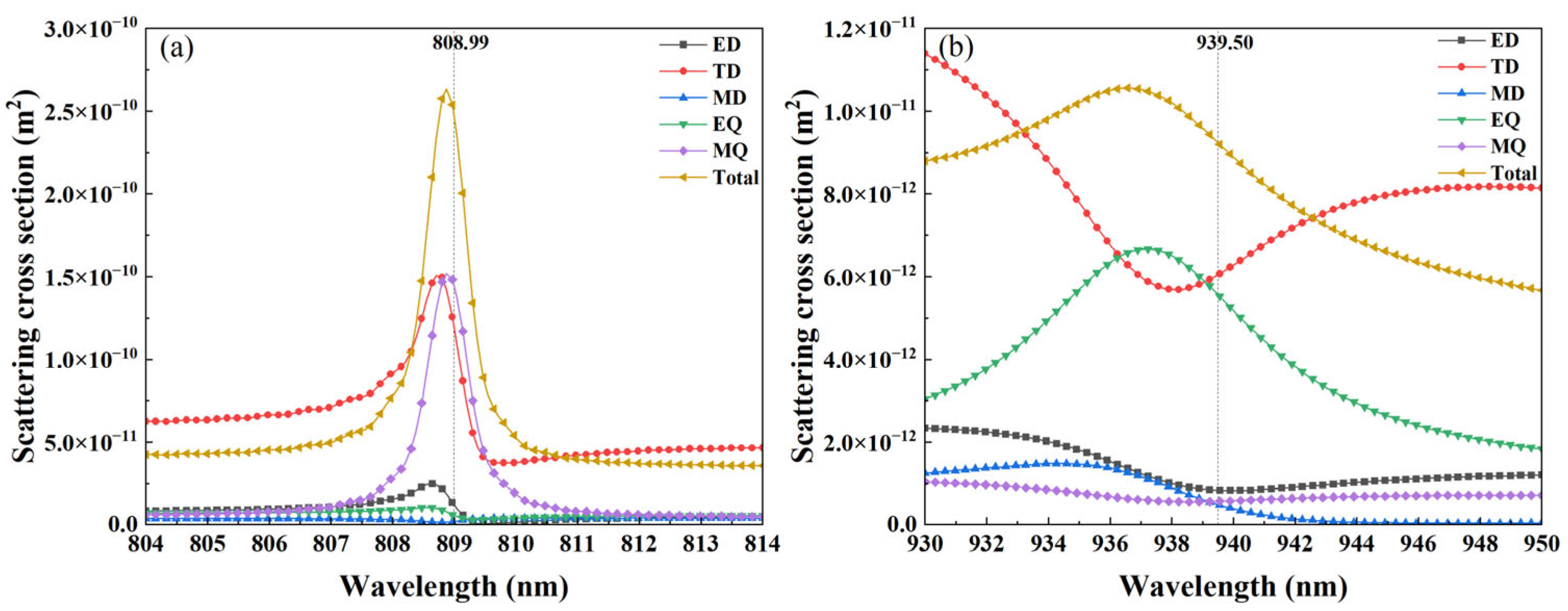

3.1. Resonance Modes Analysis of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface

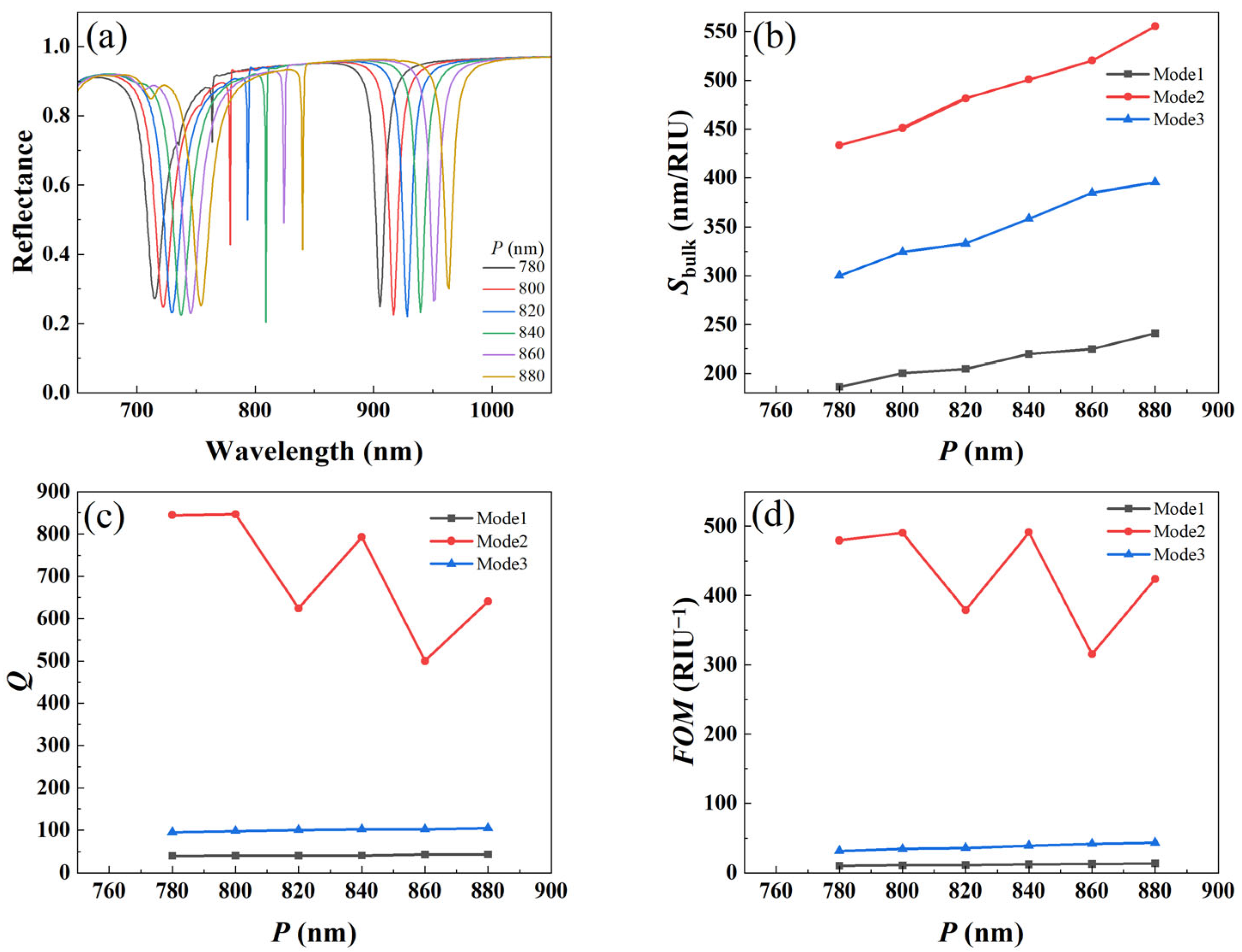

3.2. Effect of Period on Refractive Index Sensing

3.3. Effect of Size on Refractive Index Sensing

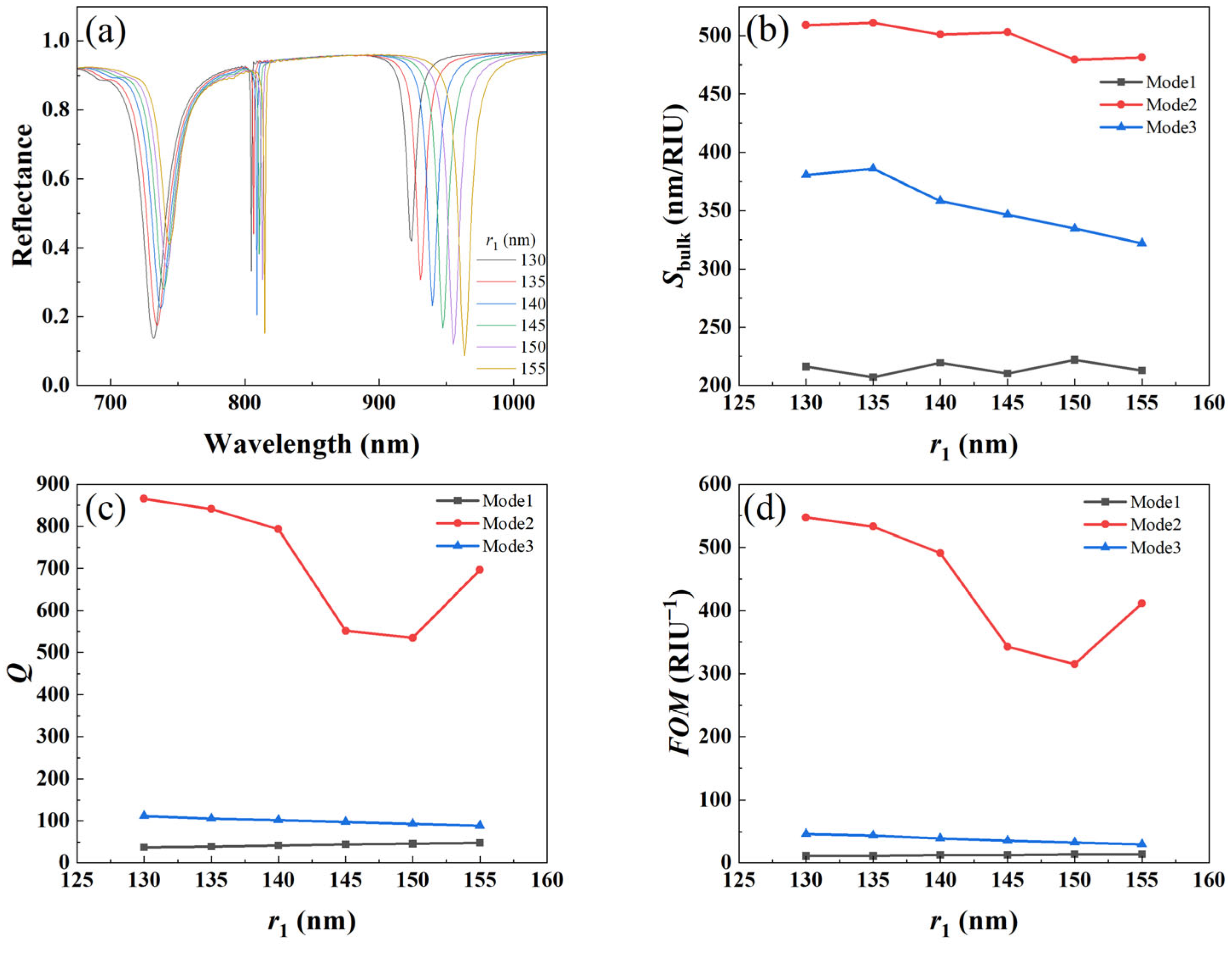

3.3.1. Effect of Radius of Large Cylinder

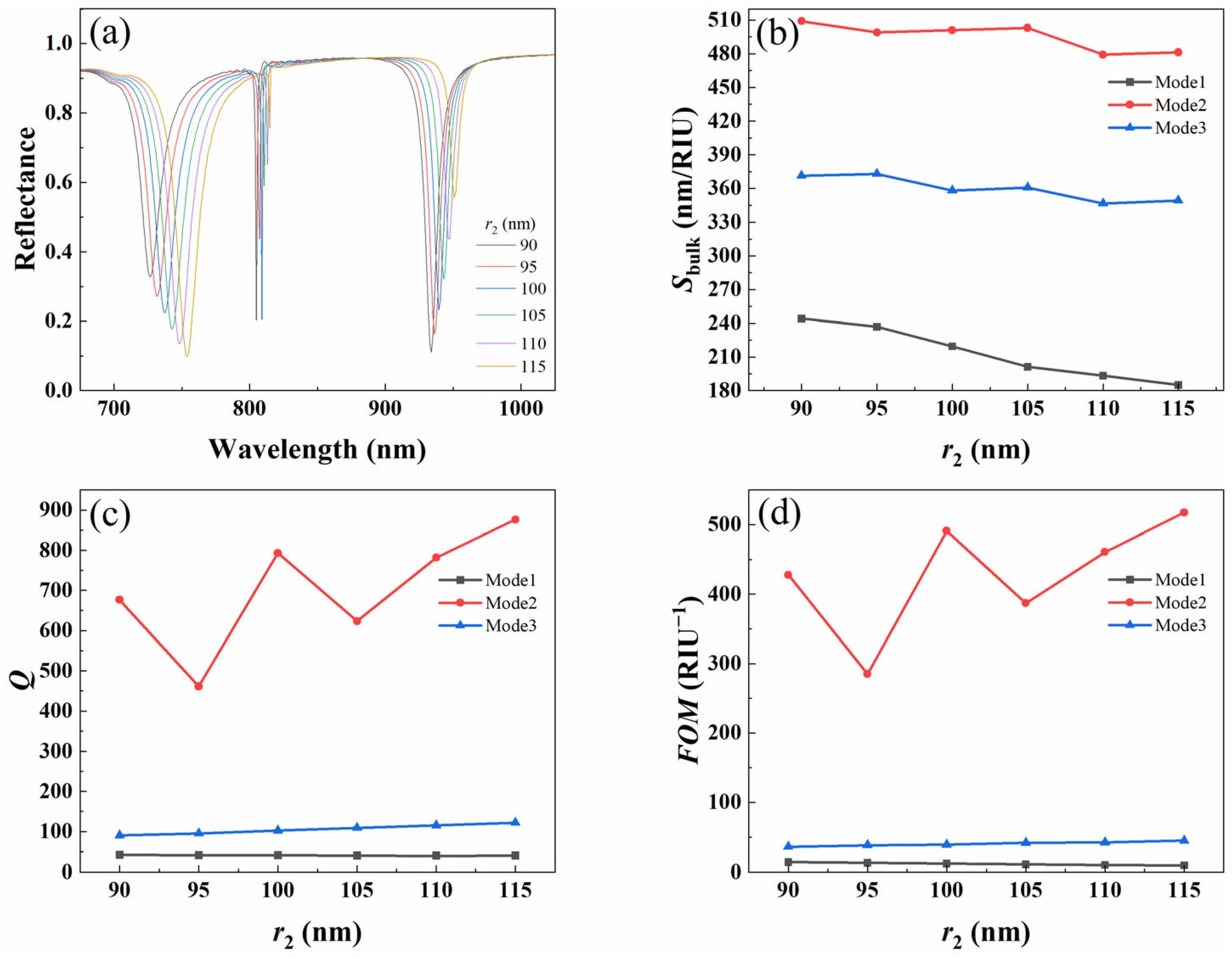

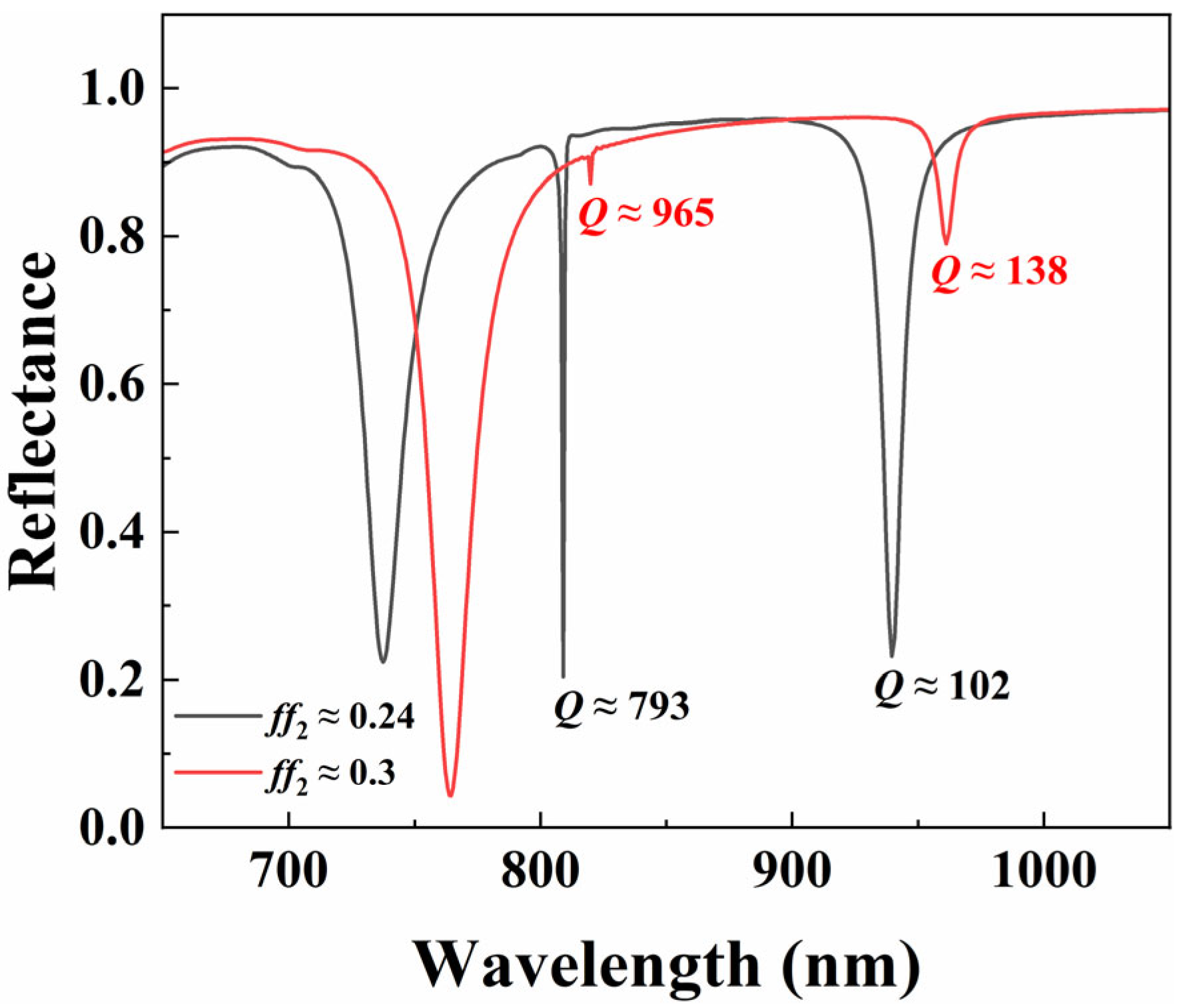

3.3.2. Effect of Radius of Small Cylinder

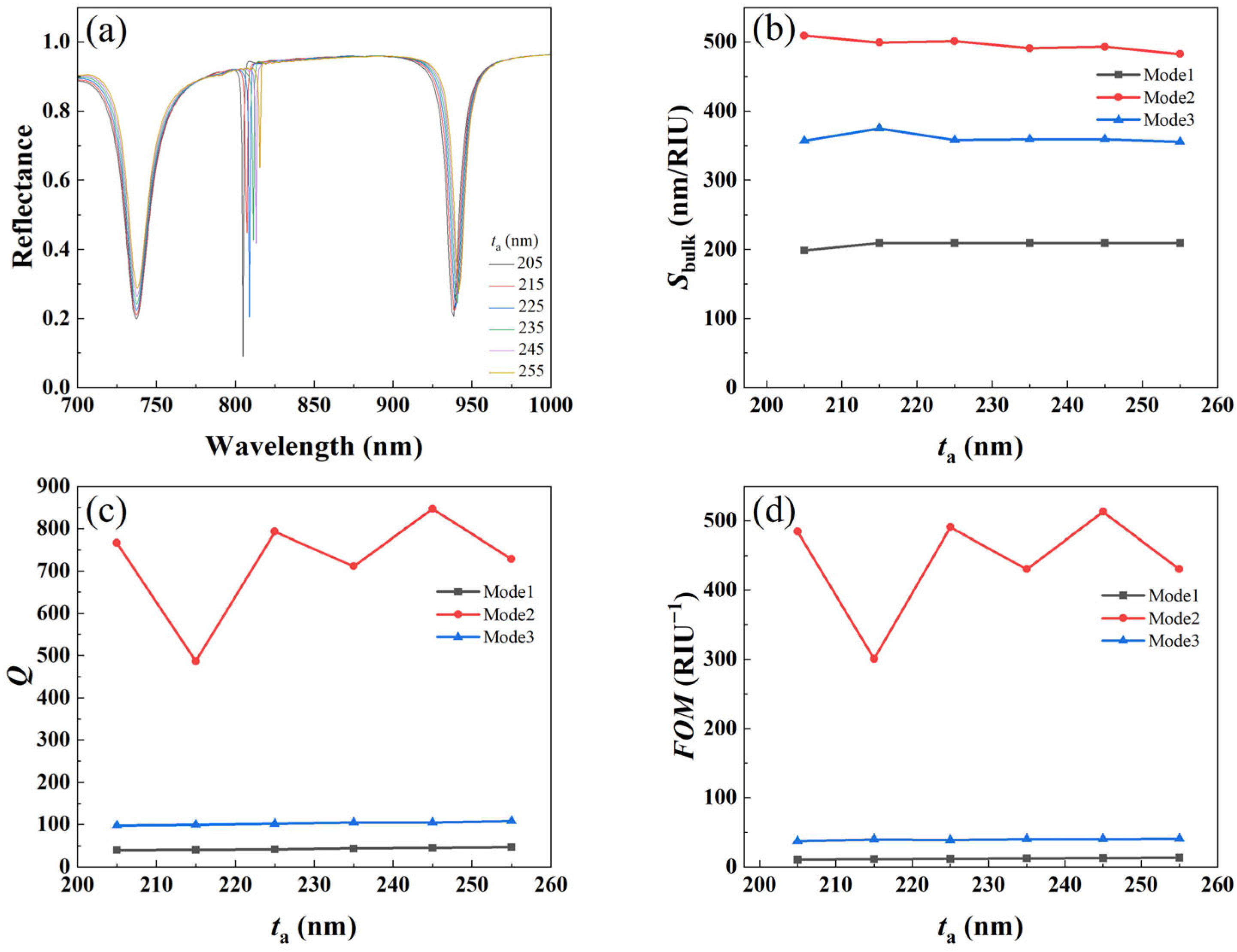

3.3.3. Effect of Cylinder Height

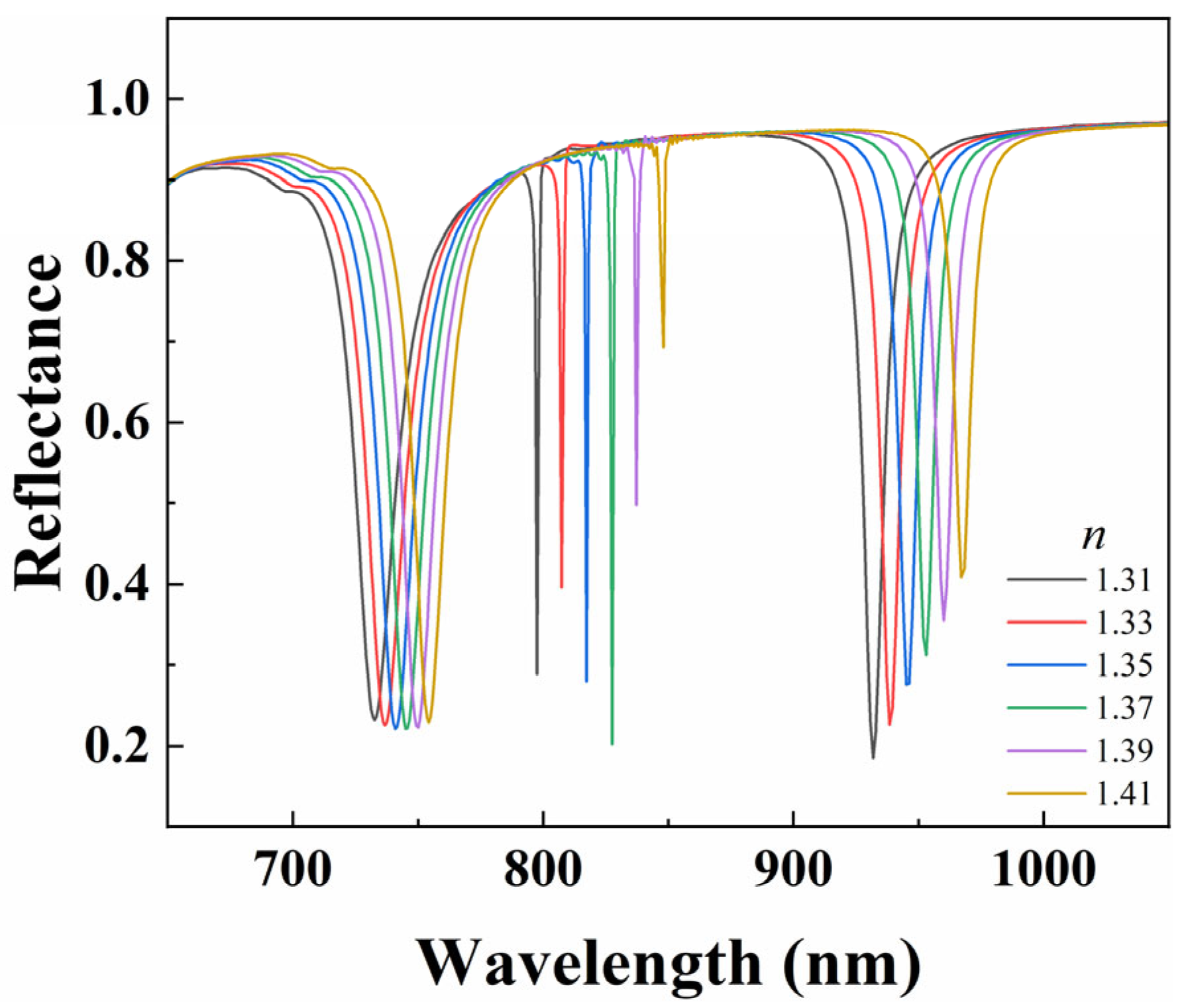

3.4. Effect of Refractive Index of Environment on Refractive Index Sensing

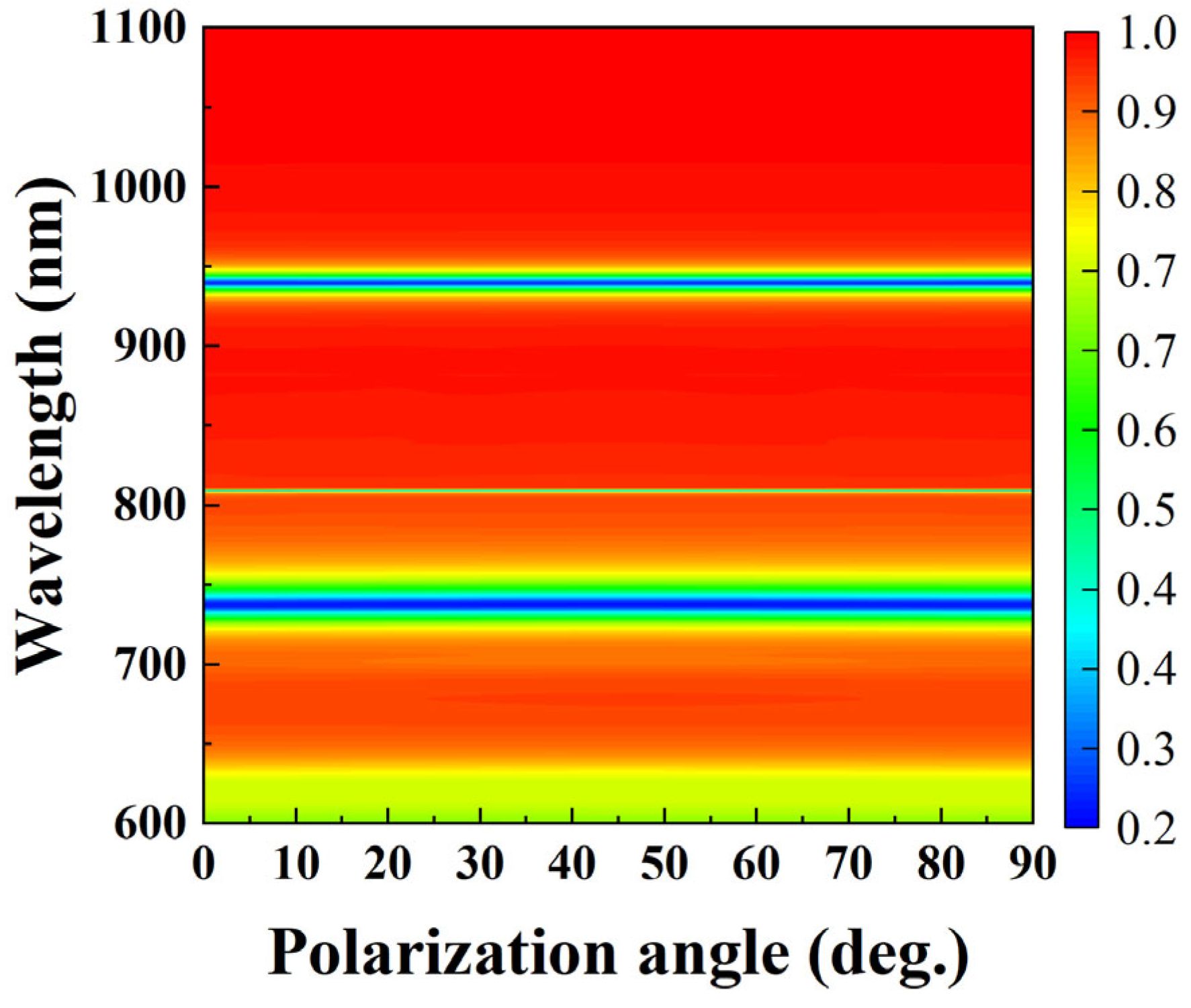

3.5. Effect of Incident Light on Refractive Index Sensing

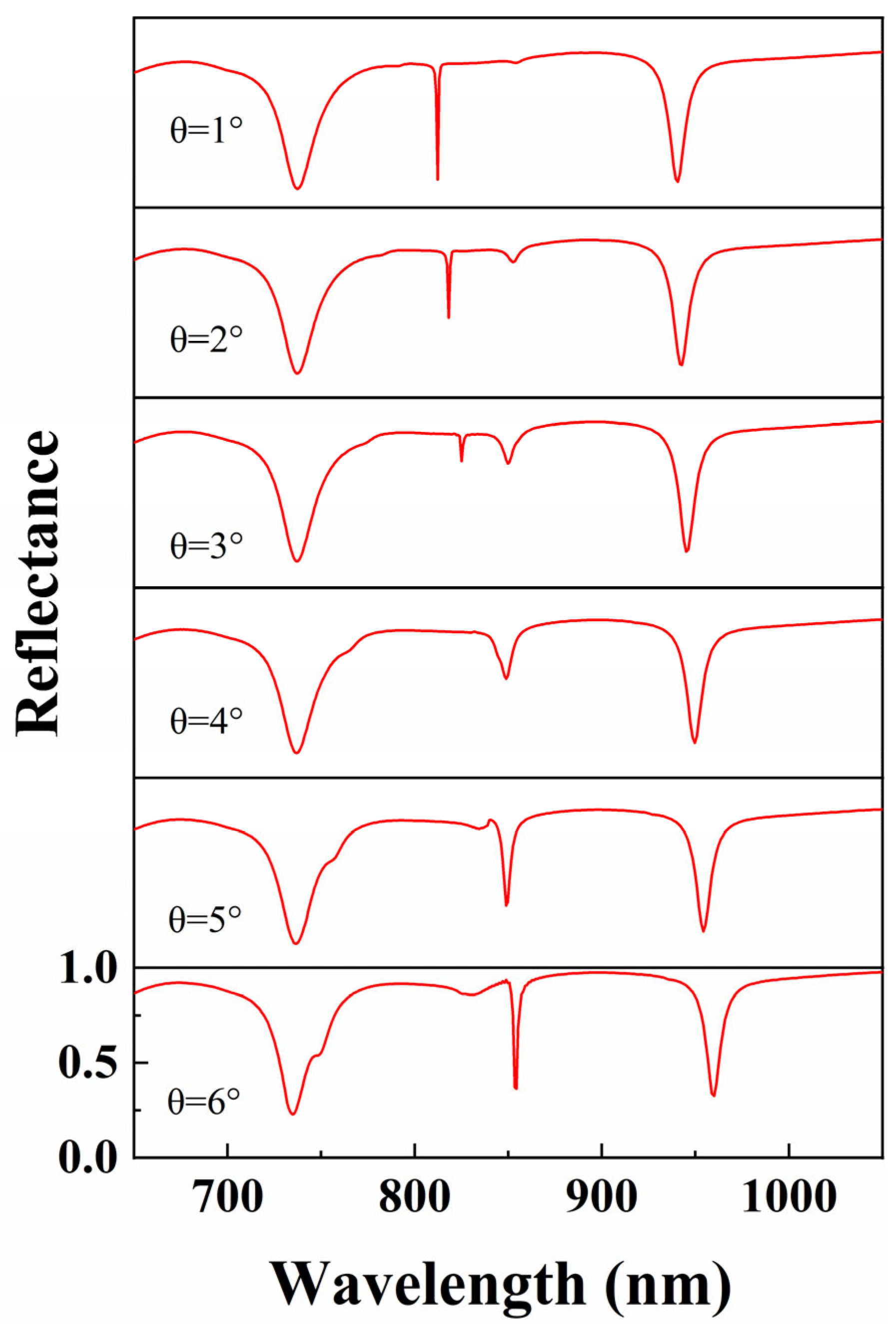

3.6. Effect of Asymmetry on Refractive Index Sensing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsu, C.W.; Zhen, B.; Stone, A.D.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Soljačić, M. Bound States in the Continuum. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; Von Neumann, J.; Wigner, E.P. On an Algebraic Generalization of the Quantum Mechanical Formalism. In The Collected Works of Eugene Paul Wigner; Wightman, A.S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; pp. 298–333. ISBN 978-3-642-08154-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, C. Polarization-Independent Toroidal Dipole Resonances Driven by Symmetry-Protected BIC in Ultraviolet Region. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshelev, K.; Favraud, G.; Bogdanov, A.; Kivshar, Y.; Fratalocchi, A. Nonradiating Photonics with Resonant Dielectric Nanostructures. Nanophotonics 2019, 8, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepetit, T.; Kanté, B. Controlling Multipolar Radiation with Symmetries for Electromagnetic Bound States in the Continuum. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 241103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.; Achaoui, Y.; Martínez, J.A.I.; Addouche, M.; Wu, Y.; Khelif, A. Observation of Ultra-High-Q Resonators in the Ultrasound via Bound States in the Continuum. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.; Evans, D.V. Water-Wave Trapping by Floating Circular Cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 2009, 633, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every, A.G.; Maznev, A.A. Elastic Waves at Periodically-Structured Surfaces and Interfaces of Solids. AIP Adv. 2014, 4, 124401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshelev, K.; Lepeshov, S.; Liu, M.; Bogdanov, A.; Kivshar, Y. Asymmetric Metasurfaces with High-Q Resonances Governed by Bound States in the Continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 193903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Luo, W.; Shi, Y.; Liu, A.Q.; et al. High-Sensitivity Optical Sensors Empowered by Quasi-Bound States in the Continuum in a Hybrid Metal-Dielectric Metasurface. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6477–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, X. Asymmetric Tetramer Metasurface Sensor Governed by Quasi-Bound States in the Continuum. Nanophotonics 2023, 12, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; He, R.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Guo, J. Quasi-Bound States in the Continuum in a Metal Nanograting Metasurface for a High Figure-of-Merit Refractive Index Sensor. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, F.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S.; Wu, X. Dual-Quasi Bound States in the Continuum Enabled Plasmonic Metasurfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2200965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Shen, Y.; Zou, Q.; Huang, Y.; Huang, K.; She, X.; Jin, C. Moisture-Driven Switching of Plasmonic Bound States in the Continuum in the Visible Region. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2209368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Optical Switching with High-Q Fano Resonance of All-Dielectric Metasurface Governed by Bound States in the Continuum. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 28334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonda, L. Resonance Reactions and Continuous Channels. Ann. Phys. 1961, 12, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xiang, J.; Feng, T.; Cao, Q.; Li, J.; Lan, S.; Liu, J. High-Q Quasibound States in the Continuum for Nonlinear Metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 253901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshelev, K.; Kruk, S.; Melik-Gaykazyan, E.; Choi, J.-H.; Bogdanov, A.; Park, H.-G.; Kivshar, Y. Subwavelength Dielectric Resonators for Nonlinear Nanophotonics. Science 2020, 367, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, T. High Q-Factor Multi-Fano Resonances in All-Dielectric Double Square Hollow Metamaterials. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 140, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ding, L.; Sabatini, R.P.; Sagar, L.K.; Bappi, G.; Paniagua-Domínguez, R.; Sargent, E.H.; Kuznetsov, A.I. Bound State in the Continuum in Nanoantenna-Coupled Slab Waveguide Enables Low-Threshold Quantum-Dot Lasing. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 9754–9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.-S.; Lee, H.-C.; Kim, K.-H.; Jeong, K.-Y.; Kwon, S.-H.; Koshelev, K.; Kivshar, Y.; Park, H.-G. Ultralow-Threshold Laser Using Super-Bound States in the Continuum. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, Y.; Arvelo, E.R.; Yesilkoy, F.; Koshelev, K.; Cianciaruso, C.; De Palma, M.; Kivshar, Y.; Altug, H. Imaging-Based Spectrometer-Less Optofluidic Biosensors Based on Dielectric Metasurfaces for Detecting Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Du, Y.; Qin, J. Ultrasensitive Terahertz Sensing with High-Q Toroidal Dipole Resonance Governed by Bound States in the Continuum in All-Dielectric Metasurface. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamim, A.M. Polarization-Independent Symmetrical Digital Metasurface Absorber. Results Phys. 2021, 24, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. Tunable Dual-Band Metamaterial Absorber at Deep-Subwavelength Scale. Results Phys. 2021, 27, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, P.; Zhao, X.; Qian, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhou, X.; Han, D.; Peng, C.; Shi, L.; et al. Optical Bound States in the Continuum in Periodic Structures: Mechanisms, Effects, and Applications. Photon. Insights 2024, 3, R01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, S.I.; Shalaev, V.M.; Boltasseva, A.; Kildishev, A.V. Formation of Bound States in the Continuum in Hybrid Plasmonic-Photonic Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 253901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Han, B. Preparation of Porous Silicon Nitride Ceramics by Freeze Drying. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 6202–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, J.; Neupane, D.; Nepal, B.; Mikhaylov, V.; Demchenko, A.; Stine, K. Preparation, Modification, Characterization, and Biosensing Application of Nanoporous Gold Using Electrochemical Techniques. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacak, J.E.; Jacak, W.A. Plasmons in Metallic Nanoclusters Exhibit Nonharmonic Phenomena. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 111, 053506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczyk, K.; David, C.; Jacak, J.; Jacak, W. On Modeling of Plasmon-Induced Enhancement of the Efficiency of Solar Cells Modified by Metallic Nano-Particles. Nanomaterials 2018, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palik, E.D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; ISBN 978-0-08-054721-3. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, W.L.; Dereux, A.; Ebbesen, T.W. Surface Plasmon Subwavelength Optics. Nature 2003, 424, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-29340-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Dal Negro, L. Engineering Non-Radiative Anapole Modes for Broadband Absorption Enhancement of Light. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 19048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Z.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.-K. Ultrasensitive Refractive Index Sensing Based on Hybrid High-Q Metasurfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 8263–8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypabekova, M.; Hagemann, A.; Kleiss, J.; Morlan, C.; Kim, S. Optimizing an Optical Cavity-Based Biosensor for Enhanced Sensitivity. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 25911–25918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beliaev, L.Y.; Kim, S.; Nielsen, B.F.S.; Evensen, M.V.; Bunea, A.-I.; Malureanu, R.; Lindvold, L.R.; Takayama, O.; Andersen, P.E.; Lavrinenko, A.V. Optical Biosensors Based on Nanostructured Silicon High-Contrast Gratings for Myoglobin Detection. Acs Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 12364–12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Fan, X.; Fang, W.; Wei, W.; Cao, R.; Li, C.; Wei, X.; Tao, J.; Wang, Y.; Kumar, S. Double-Parameter Analysis of an Asymmetric Herringbone Temperature and Refractive Index Sensor Based on All-Dielectric Metasurface. Opt. Express. 2024, 32, 28552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Dev, S.U.; Allen, M.S.; Allen, J.W.; Harutyunyan, H. Optical Bound States in the Continuum Enabled by Magnetic Resonances Coupled to a Mirror. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Du, J.; Chi, Z.; Li, N. Mid-Infrared High Performance Dual-Fano Resonances Based on All-Dielectric Metasurface for Refractive Index and Gas Sensing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Zito, G.; Torino, S.; Calafiore, G.; Penzo, E.; Coppola, G.; Cabrini, S.; Rendina, I.; Mocella, V. Label-Free Sensing of Ultralow-Weight Molecules with All-Dielectric Metasurfaces Supporting Bound States in the Continuum. Photon. Res. 2018, 6, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Goldflam, M.D.; Campione, S.; Briscoe, J.L.; Vabishchevich, P.P.; Nogan, J.; Sinclair, M.B.; Luk, T.S.; Brener, I. High Quality Factor Toroidal Resonances in Dielectric Metasurfaces. ACS Photonics 2020, 7, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-D. A High-Performance Refractive Index Sensor Based on Fano Resonance in Si Split-Ring Metasurface. Plasmonics 2018, 13, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Multipoles | Expression | Far Field Scattering Power |

|---|---|---|

| Electric dipole (P) | ||

| Magnetic dipole (M) | ||

| Toroidal dipole (T) | ||

| Electric quadrupole (Qe) | ||

| Magnetic quadrupole (Qm) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, S.; Tuersun, P.; Li, S.; Wang, M.; Pu, B. Refractive Index Sensing Properties of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201570

Lv S, Tuersun P, Li S, Wang M, Pu B. Refractive Index Sensing Properties of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(20):1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201570

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Shuqi, Paerhatijiang Tuersun, Shuyuan Li, Meng Wang, and Bojun Pu. 2025. "Refractive Index Sensing Properties of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface" Nanomaterials 15, no. 20: 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201570

APA StyleLv, S., Tuersun, P., Li, S., Wang, M., & Pu, B. (2025). Refractive Index Sensing Properties of Metal–Dielectric Yurt Tetramer Metasurface. Nanomaterials, 15(20), 1570. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15201570