Tailoring the Lithium Concentration in Thin Lithium Ferrite Films Obtained by Dual Ion Beam Sputtering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

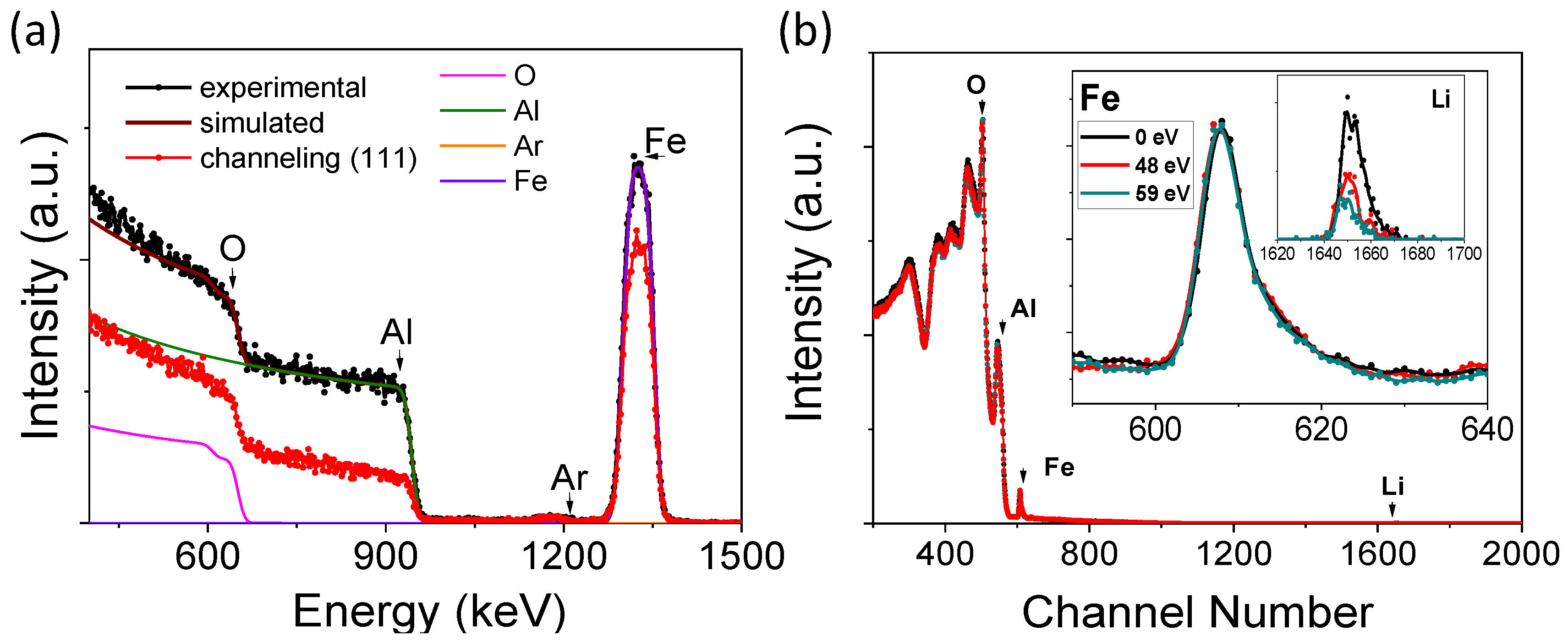

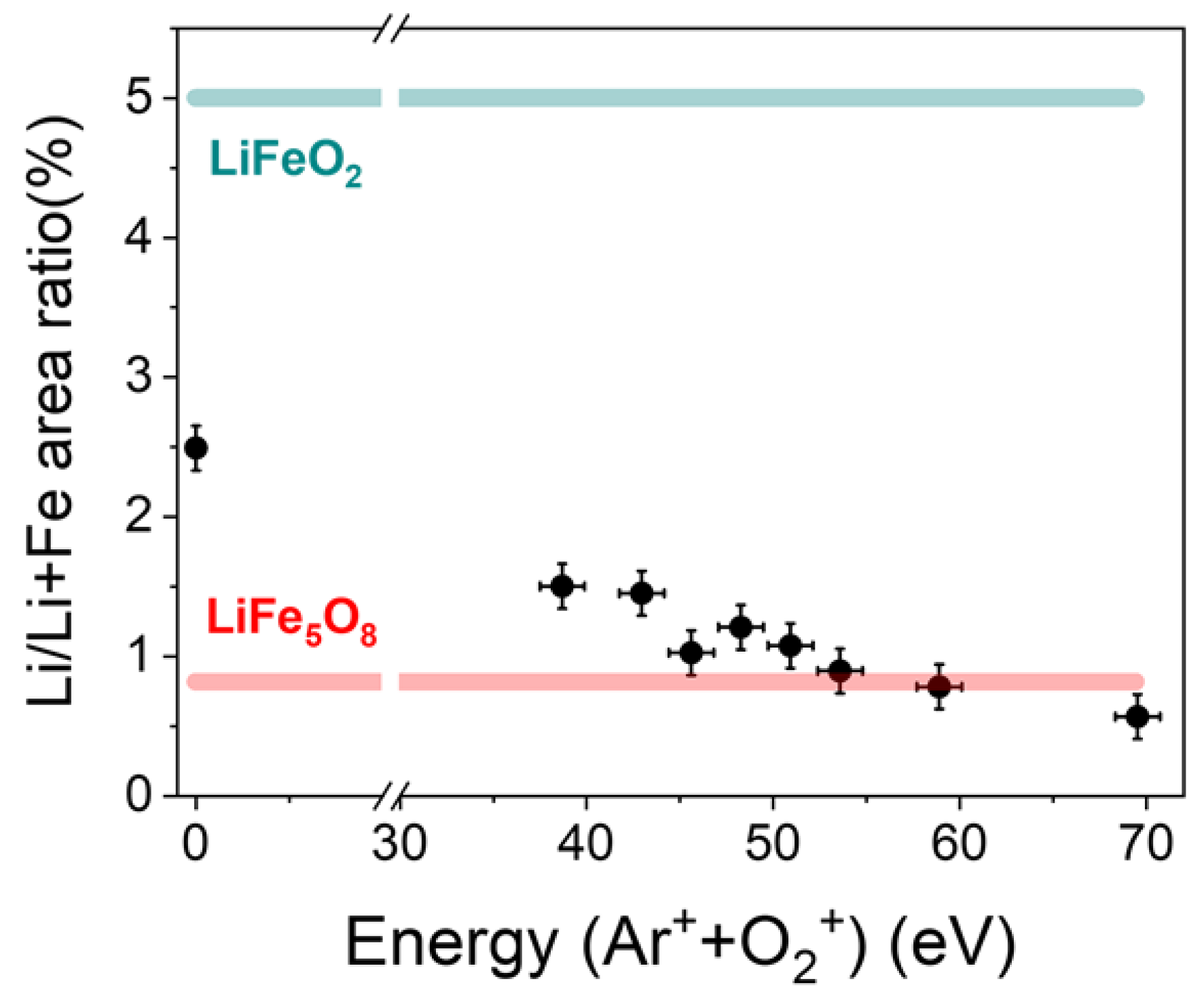

3.1. Lithium Quantification

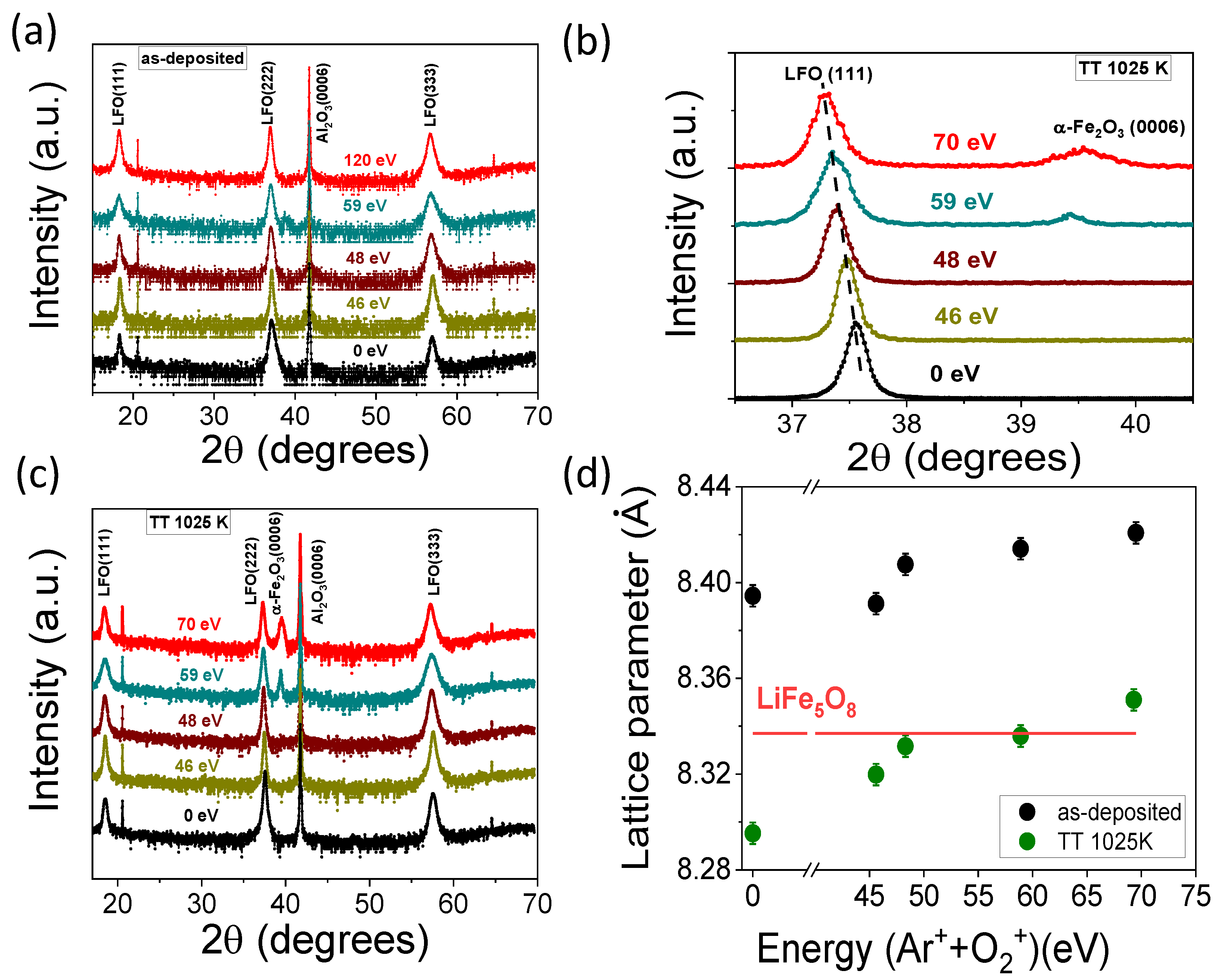

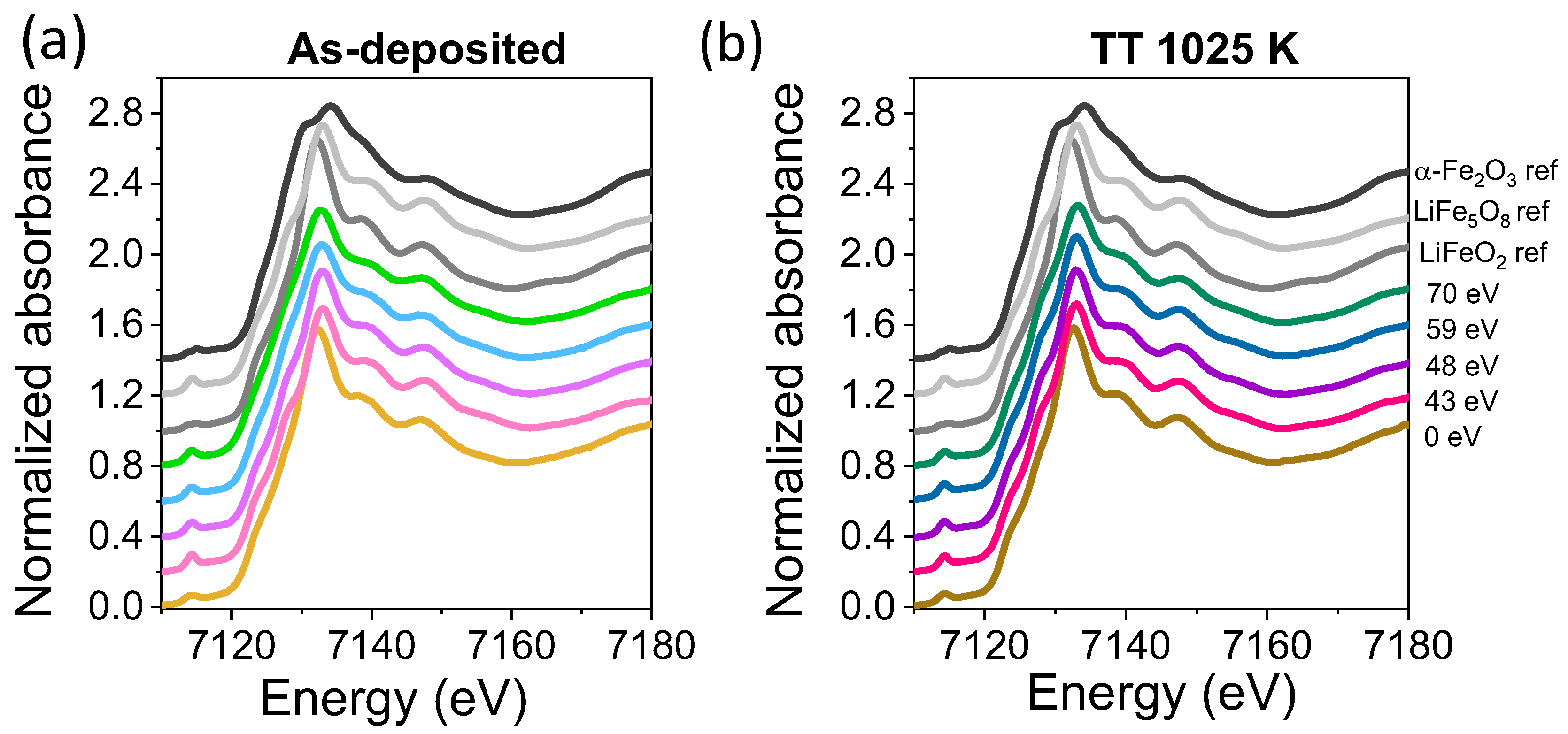

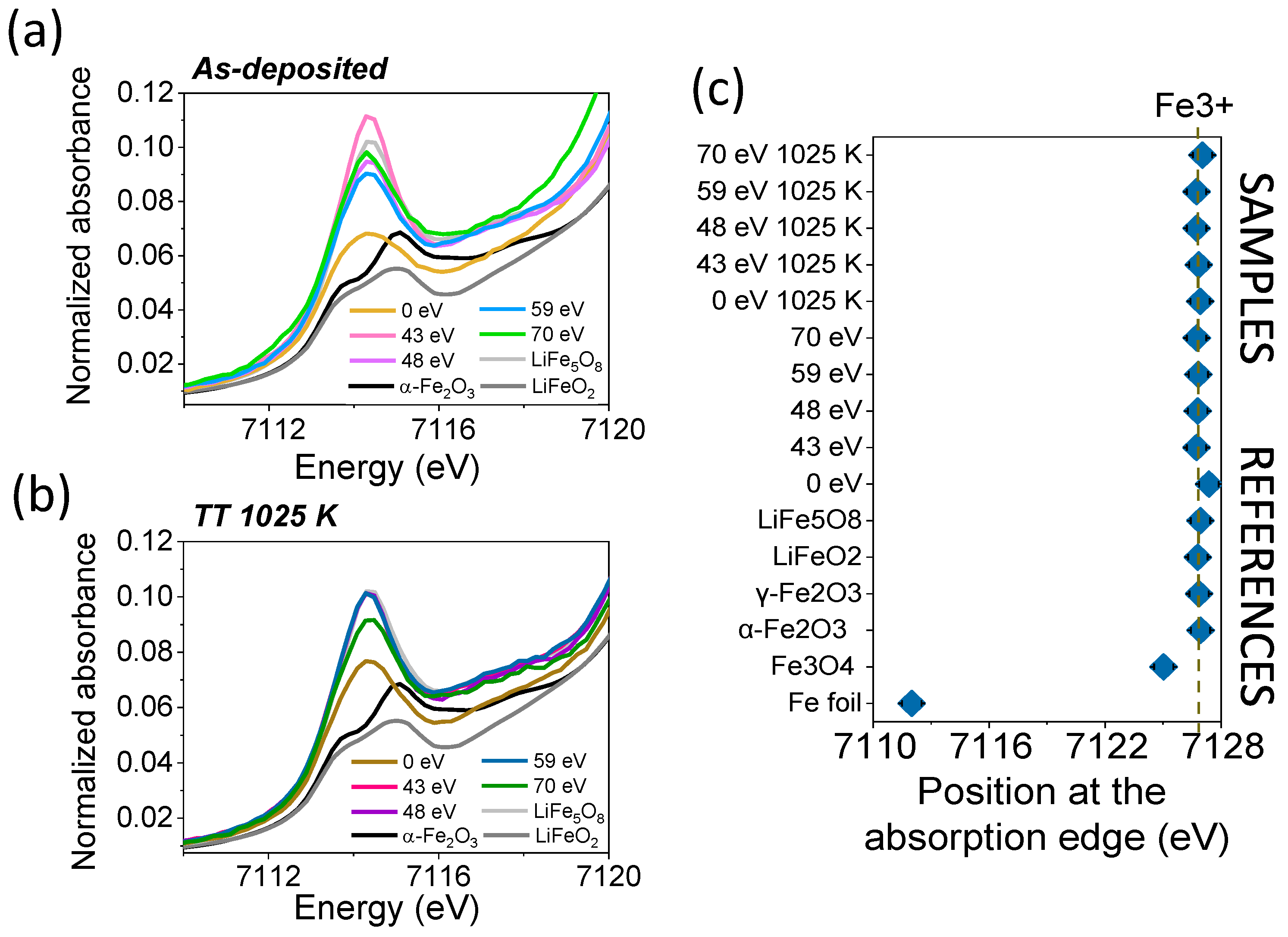

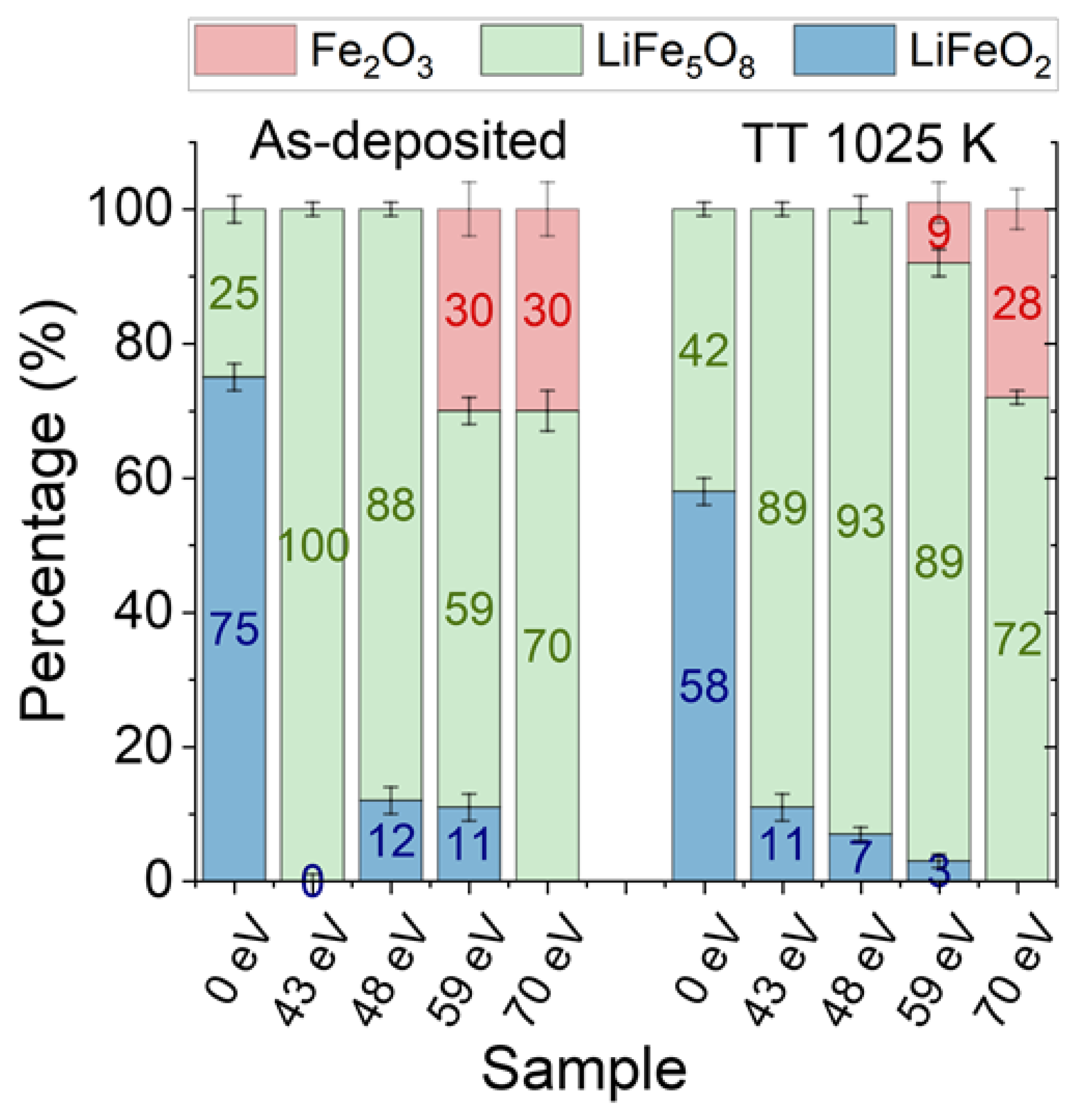

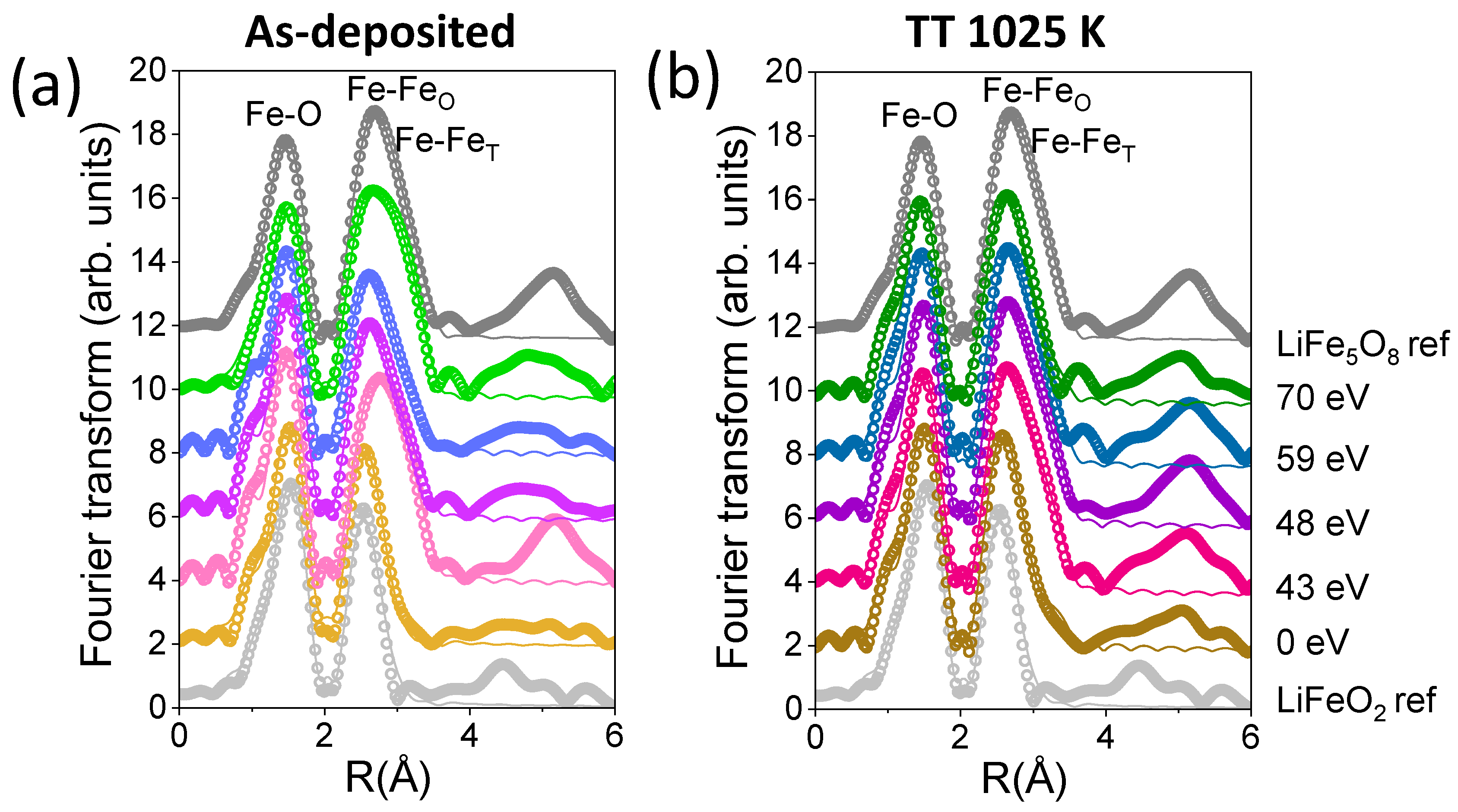

3.2. Structural and Compositional Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubs, C.; Surzhenko, O.; Thomas, R.; Osten, J.; Schneider, T.; Lenz, K.; Grenzer, J.; Hübner, R.; Wendler, E. Low damping and microstructural perfection of sub-40 nm-thin yttrium iron garnet films grown by liquid phase epitaxy. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 024416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysztofk, A.; Özoğlu, S.; McMichael, R.D.; Coy, E. Effect of strain-induced anisotropy on magnetization dynamics in Y3Fe5O12 films recrystallized on a lattice-mismatched substrate. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emori, S.; Yi, D.; Crossley, S.; Wisser, J.J.; Balakrishnan, P.P.; Khodadadi, B.; Shafer, P.; Klewe, C.; N’Diaye, A.T.; Urwin, B.T.; et al. Ultralow Damping in Nanometer-Thick Epitaxial Spinel Ferrite Thin Films. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 4273–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Channa, S.; Riddiford, L.J.; Wisser, J.J.; Mahalingam, K.; Bowers, C.T.; McConney, M.E.; N’Diaye, A.T.; Vailionis, A.; Cogulu, E.; et al. Ultra-thin lithium aluminate spinel ferrite films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy and low damping. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Riddiford, L.J.; Wisser, J.J.; Emori, S.; Suzuki, Y. Ultra-low magnetic damping in epitaxial Li0.5Fe2.5O4 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 092407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, C.; Mazumdar, D.; Iliev, M.; Marinova, V.; Ma, J.; Srinivasan, G.; Gupta, A. Structural and magnetic properties of lithium ferrite thin films: Influence of substrate on the octahedral site order. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 012507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.P.; Dobbidi, P. Conduction mechanism, dielectric, and magnetic investigation of lithium ferrite thin films deposited by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 619, 156706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-P.; Lin, C.-H.; Liu, C.-W.; Yao, Y.-D. Microwave-induced combustion synthesis of Li0.5Fe2.5O4 powder and their characterization. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 395, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Pardavi-Horvath, M. Microwave applications of soft ferrites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2000, 215–216, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, F.O.; Kammler, H.K.; Roessler, A.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Stark, W.J.; Ufheil, J.; Novak, P. Electrochemically active flame-made nanosized spinels: LiMn2O4, Li4Ti5O12 and LiFe5O8. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2007, 101, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, S.; Udhayakumar, S.; Kumaresan, L.; Patro, L.N.; Kumaran, V.; Kumar, E.S.; Navaneethan, M.; Kim, D.K.; Bharathi, K.K. Ordered LiFe5O8 thin films prepared by pulsed laser deposition as an anode material for all-solid thin film batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 454, 142318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Pan, L.; Peng, S.; Qin, L.; Bi, J.; Wu, J.; Wu, H.; Ye, Z.-G. The magnetoelectric effect in a cubic ferrimagnetic spinel LiFe5O8 with high coupling temperature. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, C.; Suchomski, C.; Wang, D.; Hahnad, H.; Brezesinski, T. In situ tuning of magnetization via topotactic lithium insertion in ordered mesoporous lithium ferrite thin films. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, L.; Guo, S.; Liu, G.; Li, R.-W.; Lu, W.D. In Situ Nanoscale Electric Field Control of Magnetism by Nanoionics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P.B. A Superstructure in Spinels. Nature 1952, 170, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahniyaz, A.; Fujiwara, T.; Song, S.-W.; Yoshimura, M. Low temperature preparation of β-LiFe5O8 fine particles by hydrothermal ball milling. Solid State Ion. 2002, 151, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, R.D.; Rode, K.; Sumesh, R.G.S.; Venkatesan, M.; Coey, J.M.D.; Shvets, I.V.; Lunney, J.G. Thin films of semiconducting lithium ferrite produced by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 5245–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cao, C.; Zhao, J. Structure and magnetic properties of epitaxial LiFe5O8 film with different growth temperatures. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, H.J.; Lunney, J.G.; Ravinder, D.; Coey, J.M.D. Magnetic properties of (111) Li0.5Fe2.504 films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1995, 140–144, 2081–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadieu, F.J.; Rani, R.; Mendoza, W.; Peng, B.; Shaheen, S.A.; Hurben, M.J.; Patton, C.E. Static magnetic and microwave properties of Li-ferrite films prepared by pulsed laser Deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, M.; Lu, L.; Mi, S.-B.; Wang, H. Strain-tunable magnetic properties of epitaxial lithium ferrite thin film on MgAl2O4 substrates. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 5598–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, M.; Lu, L.; Mi, S.B.; Wang, H. Ultra-low temperature epitaxial growth of lithium ferrite thin films by high-pressure sputtering. CrystEngComm 2015, 17, 8256–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukya, B.; Negi, D.S.; Sahu, R.; Pachauri, N.; Gupta, A.; Datta, R. Structural characterization of epitaxial LiFe5O8 thin films grown by chemical vapor deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 668, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, S.-D.; Mi, S.-B. Epitaxial growth and interface of (111)-oriented spinel Li0.5Fe2.5O4 film on SrTiO3(001) substrate. Mater. Lett. 2023, 351, 135037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaykan, L.S.; Mazurenko, J.S.; Sijo, A.K.; Makovysyn, V.I. Structural properties of magnesium-substituted lithium ferrites. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 2739–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-P.; Hu, S.-H. Electrical and magnetic properties of magnesium-substituted lithium ferrite. Ceram. Int. 2010, 36, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahoney, D.; Channa, C.; Zheng, Y.; Vailionis, A.; Shafer, P.; N’Diaye, A.T.; Klewe, C.; Suzuki, Y. Aluminum substitution in low damping epitaxial lithium ferrite films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 123, 172405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Cubero, A.; Borge, M.J.G.; Gordillo, N.; Gutiérrez, P.C.; Olivares, J.; PérezCasero, R.; Ynsa, M.D. Current status and future developments of the ion beam facility at the centre of micro-analysis of materials in Madrid. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneta, V.; Kafkarkou, A.; Kokkoris, M.; Lagoyannis, A. Differential cross-section measurements for the 7Li(p,p0)7Li, 7Li(p,p1)7Li,7Li(p,a0)4He, 19F(p,p0)19F, 19F(p,a0)16O and 19F(p,a1,2)16O reactions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2012, 288, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Arrabal, R.; Panizo-Laiz, M.; Fujita, K.; Mima, K.; Yamazaki, A.; Kamiya, T.; Orikasa, Y.; Uchimoto, Y.; Sawada, H.; Okuda, C.; et al. Meso-scale characterization of lithium distribution in lithium-ion batteries using ion beam analysis techniques. J. Power Sources 2015, 299, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.V.; Pecquenard, B.; Vinatier, P.; Wannek, C.; Levasseur, A.; Moretto, P. RBS and NRA analyses of lithium inserted amorphous Li1+xNiVO4 films. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2006, 246, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. SIMNRA, a simulation program for the analysis of NRA, RBS and ERDA. AIP Conf. Proc. 1999, 475, 541. [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli, L.; Marini, C.; Olszewski, W.; Ávila-Pérez, M.; Ramanan, N.; Guilera, G.; Cuarteto, V.; Klementiev, K.; Naurang, L.S. CLÆSS: The hard X-ray absorption beamline of the ALBA CELLS synchrotron. Cogent Phys. 2016, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, B.; Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: Data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, D.; Serrano, A.; Jaafar, M.; Prieto, P.; Kamra, A.; González-Ruano, C.; Aliev, F.G. Microwave Field-Induced Changes in Raman Modes and Magnetic Force Images of Antiferromagnetic NiO Films. Condens. Matter 2024, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Feijoo, I.; Serrano, A.; Hernández-Gómez, C.; Cuñado, J.L.F.; Prieto, P. Influence of the Substrate on the Exchange Coupling of NiO/FeCo Bilayers. Crystals 2024, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Miralles, C.; Serrano, A.; Prieto, P.; Guzmán-Mínguez, J.; Prieto, J.E.; Friedel, A.M.; García-Martín, E.; Fernández, J.F.; Quesada, A. Quantifying Li-content for compositional tailoring of lithium ferrite ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 3351–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. Thin film deposition from dual ion beam sputtering system. CSI Trans. 2019, 7, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T. Assignment of pre-edge peaks in K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of 3d transition metal compounds: Electric dipole or quadrupole? X-ray Spectrom. 2008, 37, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, M.; Partzsch, G.M.; Bernhardt, B.; Lattard, D. Determination of the iron oxidation state in basaltic glasses using XANES at the K-edge. Chem. Geol. 2005, 220, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Zuazo, J.; Chainani, A.; Taguchi, M.; Malterre, D.; Serrano, A.; Castro, G.R. Electronic structure of FeO, alpha-Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 epitaxial films using high-energy spectroscopies. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 235148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuin, M.; Serrano, A.; Chaboy, J.; García, M.A.; Carmona, N. XAS study of Mn, Fe and Cu as indicators of historical glass decay. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2013, 28, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malferrari, D.; Castellini, E.; Bernini, F.; Serrano-Rubio, A.; Castro, G.R.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I.; Caleffi, M.; Brigatti, M.F.; Borsaria, M. Chemical trapping of gaseous H2S at high and low partial pressures by an iron complex immobilized inside the montmorillonite interlayer. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 265, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newville, M.; Ravel, B.; Haskel, D.; Rehra, J.J.; Stern, E.A.; Yacoby, Y. Analysis of multiple-scattering XAFS data using theoretical standards. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 1995, 208–209, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Permien, S.; Rana, J.; Krengel, M.; Sun, F.; Schumacher, G.; Bensch, W.; Banhart, J. Investigation of electronic and local structural changes during lithium uptake and release of nano-crystalline NiFe2O4 by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Power Sources 2017, 342, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, P.; Serrano, A.; Rojas-Hernandez, R.E.; Gorgojo, S.; Prieto, J.E.; Soriano, L. Spinel to disorder rock-salt structural transition on (111) nickel ferrite thin films tailored by Ni content. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 910, 164905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, N.; Khodadadi, B.; Althammer, M.; Singh, A.V.; Loukya, B.; Datta, R.; Iliev, M.; Bezmaterykh, L.; Gudim, I.; Mewes, T.; et al. Study of structural and ferromagnetic resonance properties of spinel lithium ferrite (LiFe5O8) single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 233907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, M.N.; Ivanov, V.G.; Todorov, N.D.; Marinova, V.; Abrashev, M.V.; Petrova, R.; Wang, Y.Q.; Litvinchuk, A.P. Lattice dynamics of the α and β phases of LiFe5O8. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 174111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytan, E.; Debnath, B.; Kargar, F.; Barlas, Y.; Lacerda, M.M.; Li, J.X.; Lake, R.K.; Shi, J.; Balandin, A.A. Spin-phonon coupling in antiferromagnetic nickel oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 11, 252402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, A.; Fernandez, J.F.; Rodríguez de la Fuente, O.; García, M.A. A novel route to obtain metal and oxide nanoparticles co-existing on a substrate. Mater. Today Chem. 2017, 4, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Shell | N | R (Å) | DW (Å2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiFeO2 reference | Fe-O | 6 | 2.002 (2) | 0.008 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 4 | 3.001 (7) | 0.012 (2) | |

| LiFe5O8 reference | Fe-O | 5.2 | 1.96 (1) | 0.010 (1) |

| Fe-Fe | 4 | 3.02 (2) | 0.013 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 6 | 3.48 (1) | 0.016 (5) | |

| LFO 0 eV | Fe-O | 5.85 (7) | 1.998 (5) | 0.008 (1) |

| Fe-Fe | 5.1 (3) | 3.016 (5) | 0.014 (2) | |

| LFO 43 eV | Fe-O | 4.9 (9) | 1.954 (6) | 0.008 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 2.4 (4) | 3.01 (2) | 0.009 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.1 (5) | 3.48 (1) | 0.011 (5) | |

| LFO 48 eV | Fe-O | 5.07 (8) | 1.965 (5) | 0.008 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 3.6 (5) | 3.00 (1) | 0.012 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.9 (5) | 3.47 (6) | 0.012 (6) | |

| LFO 59 eV | Fe-O | 5.0 (8) | 1.974 (5) | 0.009 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 4.1 (5) | 3.00 (1) | 0.014 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.6 (4) | 3.47 (2) | 0.012 (6) | |

| LFO 70 eV | Fe-O | 4.7 (1) | 1.969 (6) | 0.009 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 4.7 (5) | 3.01 (1) | 0.014 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.3 (4) | 3.483 (9) | 0.011 (4) | |

| LFO 0 eV 1025 K | Fe-O | 5.1 (9) | 1.987 (6) | 0.008 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 3.8 (4) | 3.00 (1) | 0.010 (3) | |

| Fe-Fe | 2.2 (2) | 3.50 (2) | 0.013 (1) | |

| LFO 43 eV 1025 K | Fe-O | 5.1 (1) | 1.965 (6) | 0.009 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 3.4 (4) | 3.00 (2) | 0.011 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.2 (5) | 3.48 (1) | 0.012 (5) | |

| LFO 48 eV 1025 K | Fe-O | 5.2 (1) | 1.965 (6) | 0.009 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 3.2 (4) | 3.01 (1) | 0.010 (4) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.6 (5) | 3.49 (1) | 0.013 (5) | |

| LFO 59 eV 1025 K | Fe-O | 5.0 (1) | 1.962 (8) | 0.009 (2) |

| Fe-Fe | 3.4 (7) | 3.01 (3) | 0.011 (6) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.7 (9) | 3.48 (2) | 0.015 (9) | |

| LFO 70 eV 1025 K | Fe-O | 5.6 (1) | 1.973 (4) | 0.011 (3) |

| Fe-Fe | 5.0 (8) | 3.01 (3) | 0.014 (7) | |

| Fe-Fe | 4.2 (6) | 3.46 (4) | 0.018 (8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prieto, P.; Hernández-Gómez, C.; Román-Sánchez, S.; París-Ogáyar, M.; Gorni, G.; Prieto, J.E.; Serrano, A. Tailoring the Lithium Concentration in Thin Lithium Ferrite Films Obtained by Dual Ion Beam Sputtering. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141220

Prieto P, Hernández-Gómez C, Román-Sánchez S, París-Ogáyar M, Gorni G, Prieto JE, Serrano A. Tailoring the Lithium Concentration in Thin Lithium Ferrite Films Obtained by Dual Ion Beam Sputtering. Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(14):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141220

Chicago/Turabian StylePrieto, Pilar, Cayetano Hernández-Gómez, Sara Román-Sánchez, Marina París-Ogáyar, Giulio Gorni, José Emilio Prieto, and Aida Serrano. 2024. "Tailoring the Lithium Concentration in Thin Lithium Ferrite Films Obtained by Dual Ion Beam Sputtering" Nanomaterials 14, no. 14: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141220

APA StylePrieto, P., Hernández-Gómez, C., Román-Sánchez, S., París-Ogáyar, M., Gorni, G., Prieto, J. E., & Serrano, A. (2024). Tailoring the Lithium Concentration in Thin Lithium Ferrite Films Obtained by Dual Ion Beam Sputtering. Nanomaterials, 14(14), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141220