Unconventional Approaches to Prepare Triazine-Based Liquid Crystal Dendrimers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

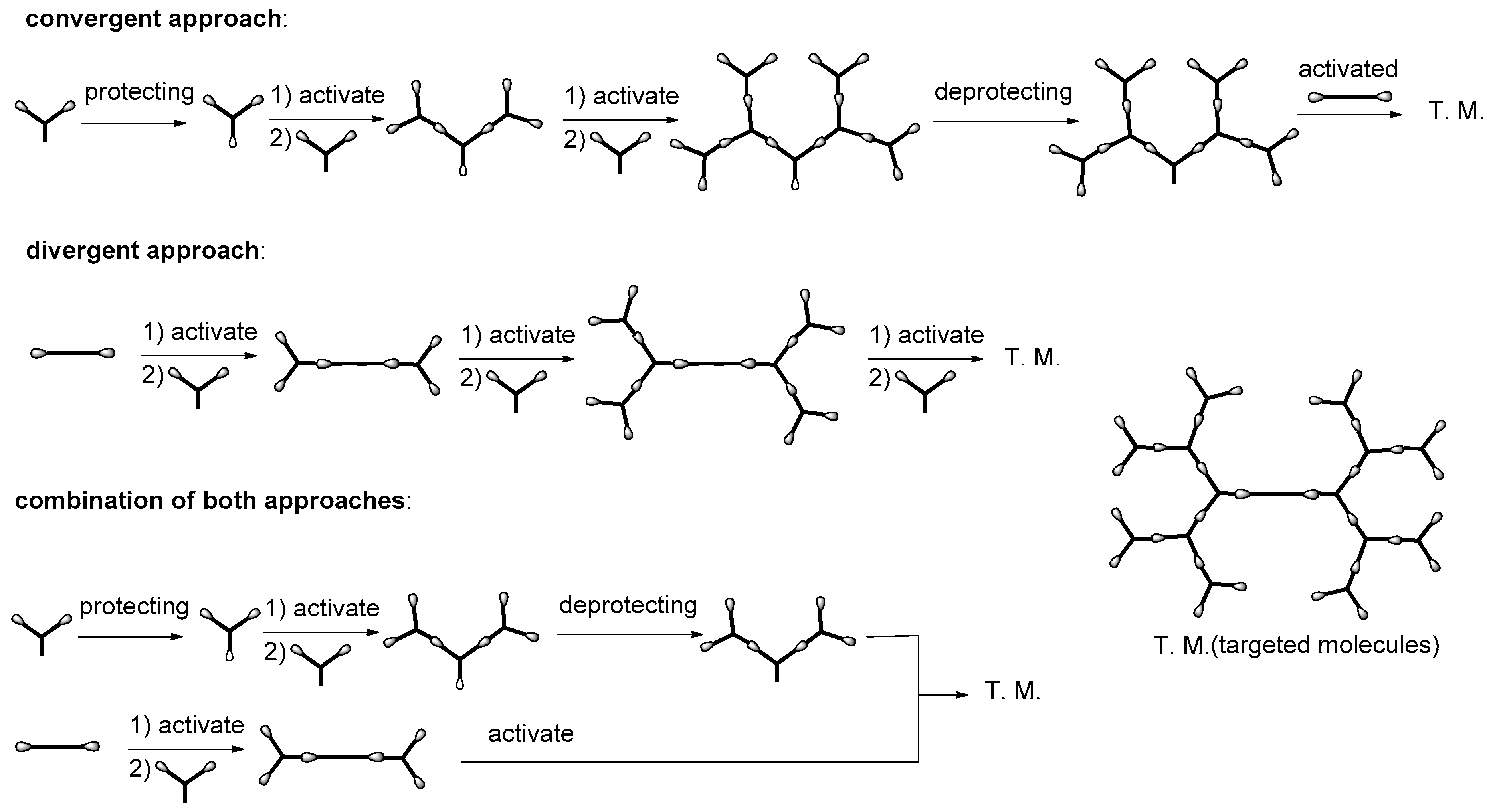

2. Formation of Triazine-Based LC Dendrimers by Manipulating Their Molecular Morphology

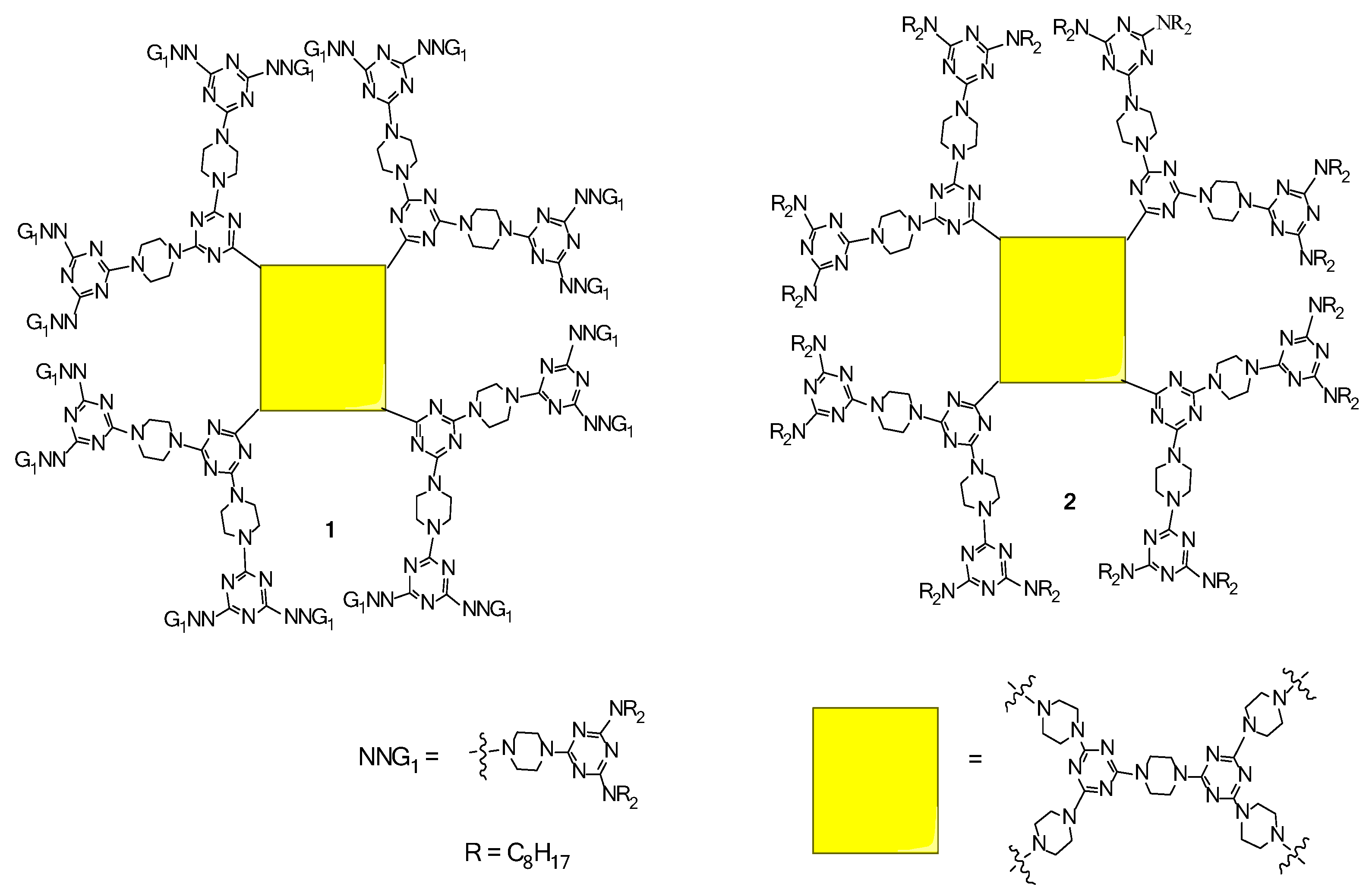

2.1. LC Dendrimers with C2 Symmetry

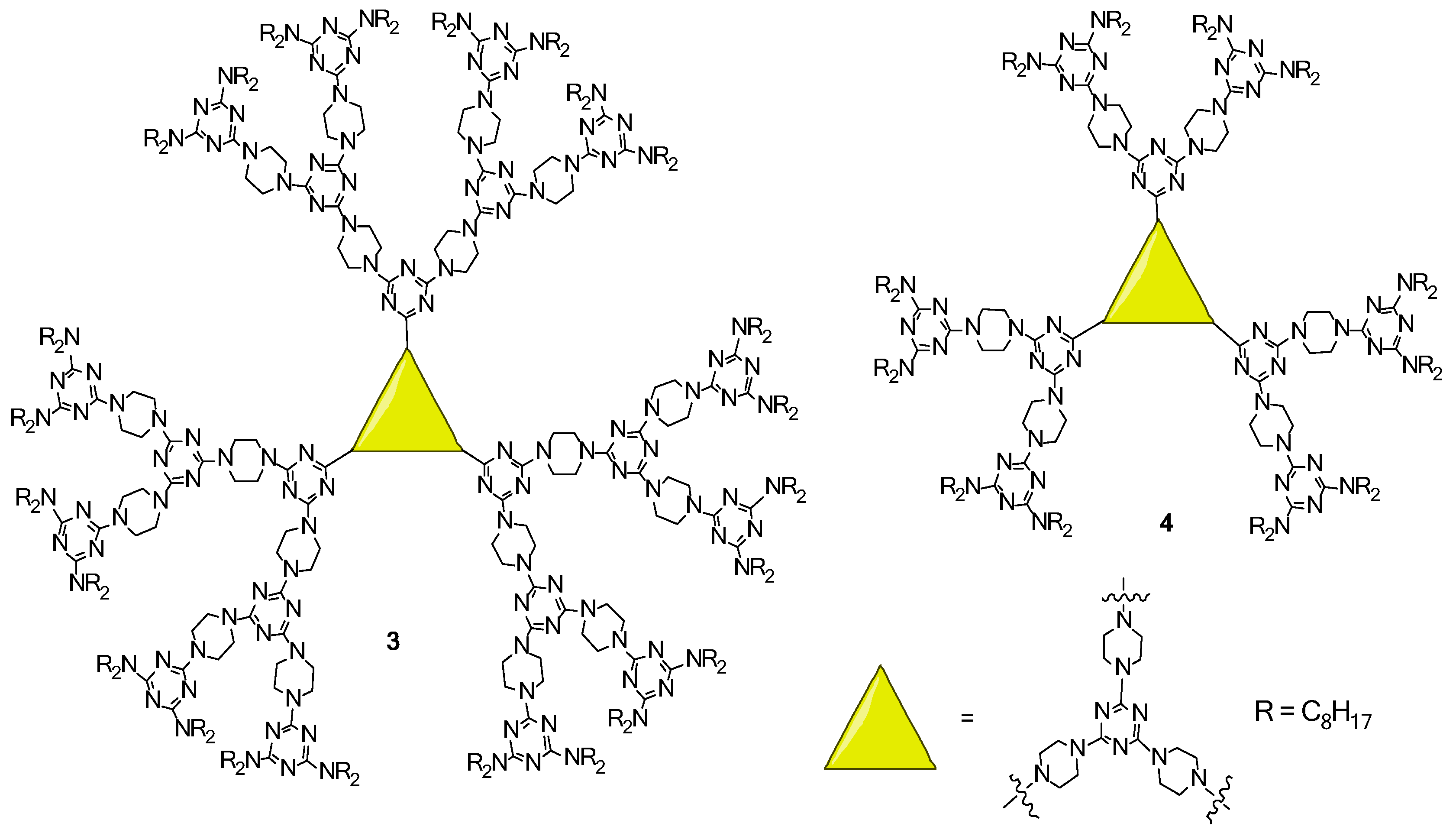

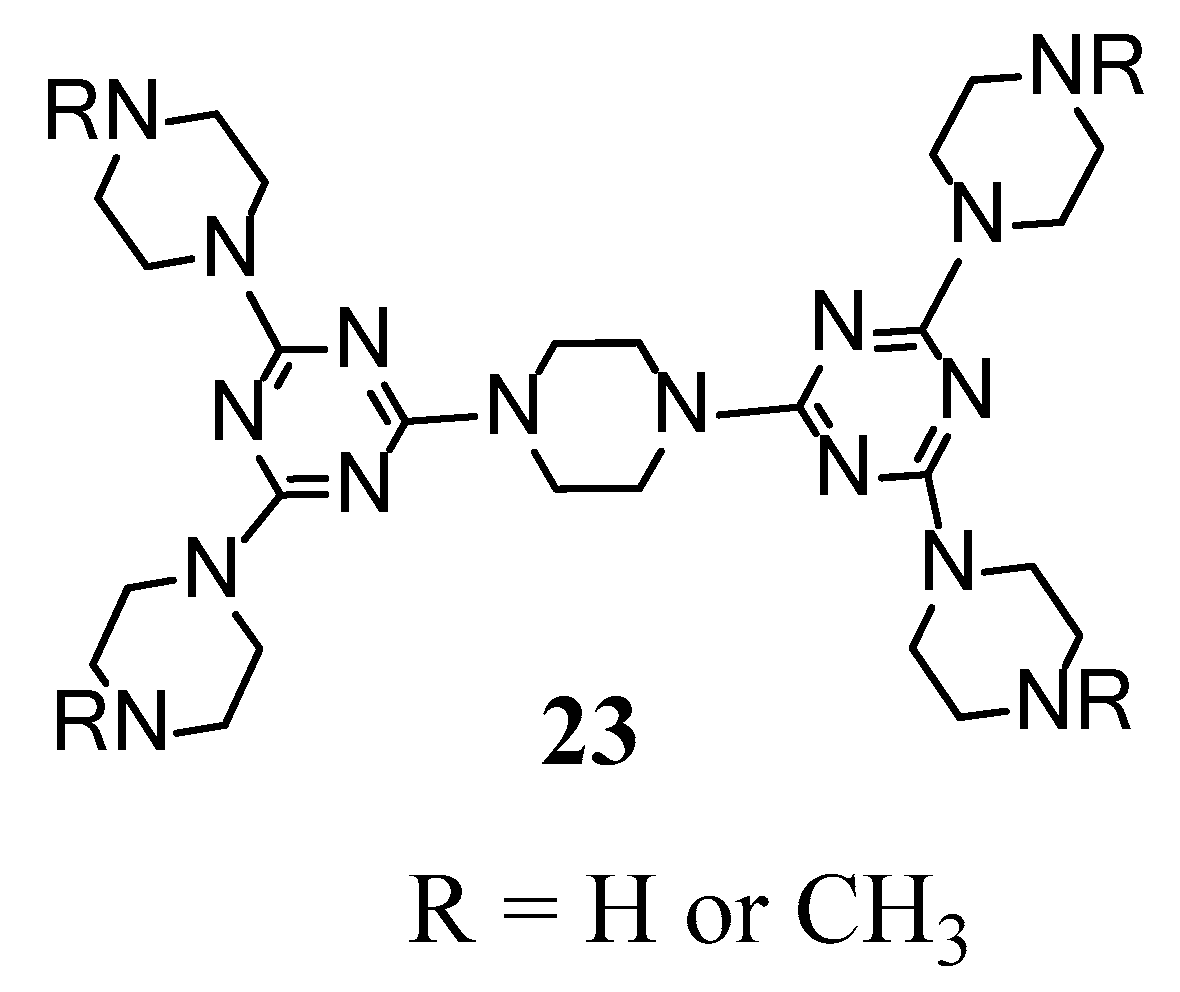

2.2. LC Dendrimers with C3 Symmetry

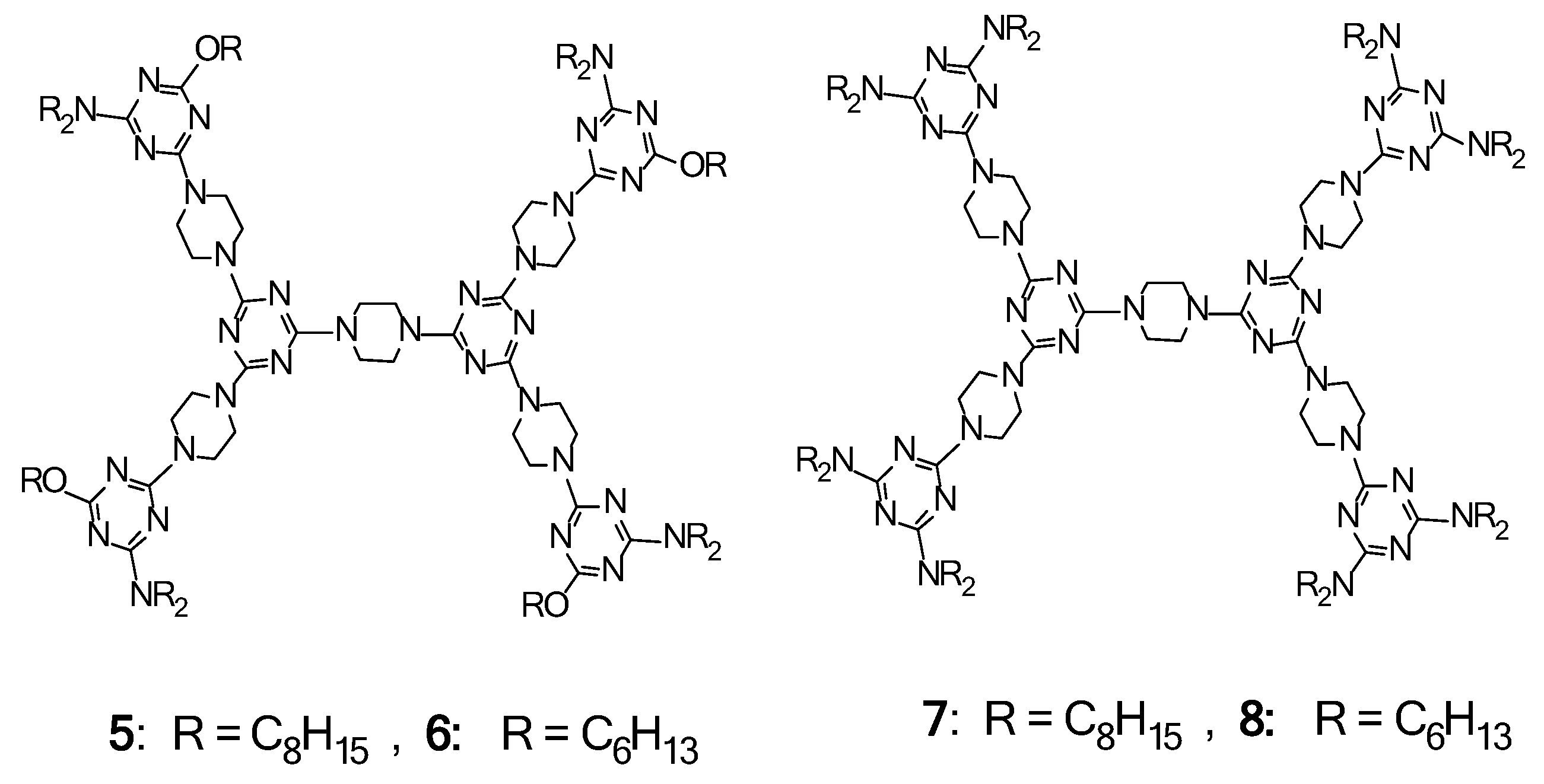

2.3. LC Dendrimers with the Loss of C2 Symmetry by Changing the Peripheral Groups

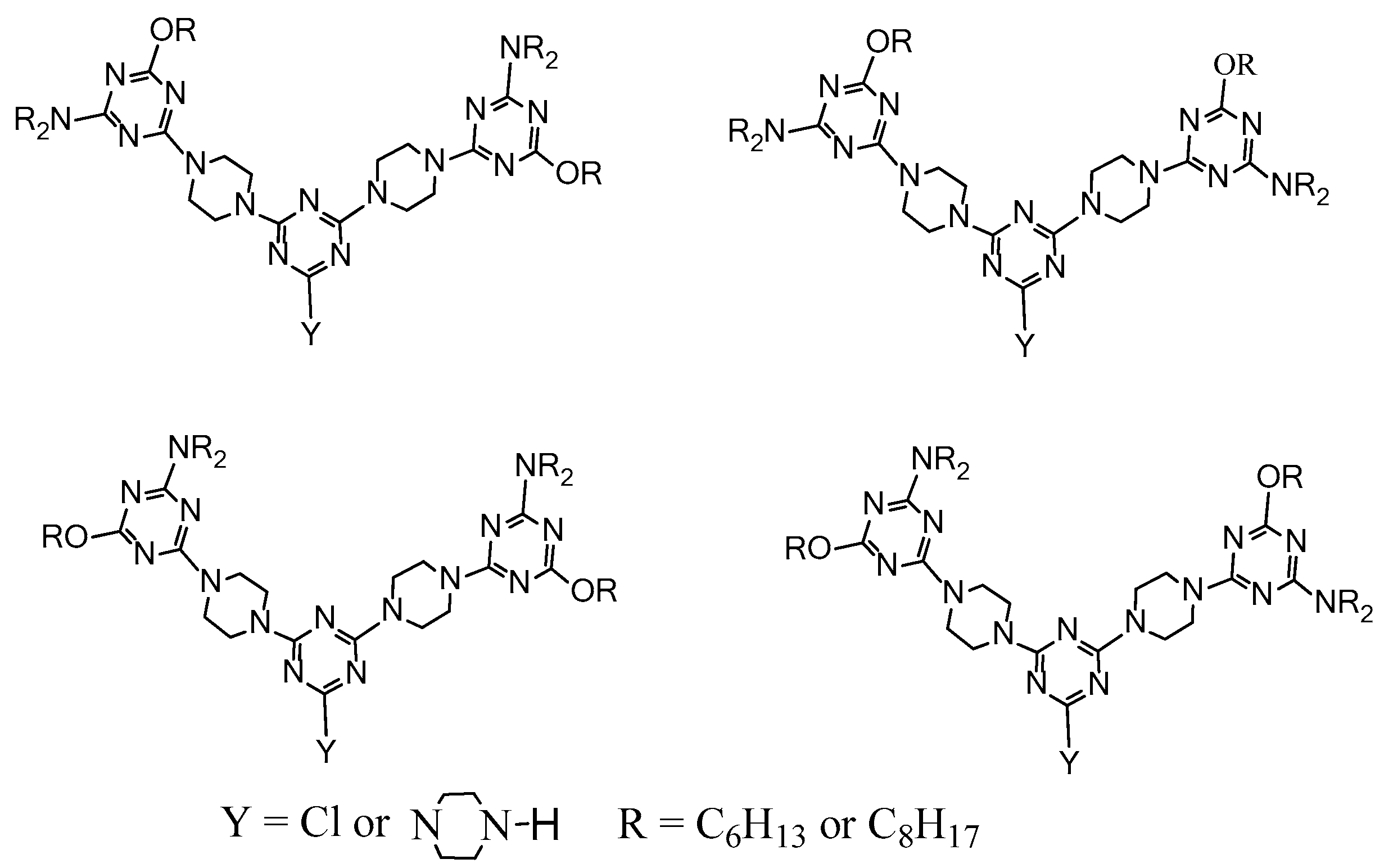

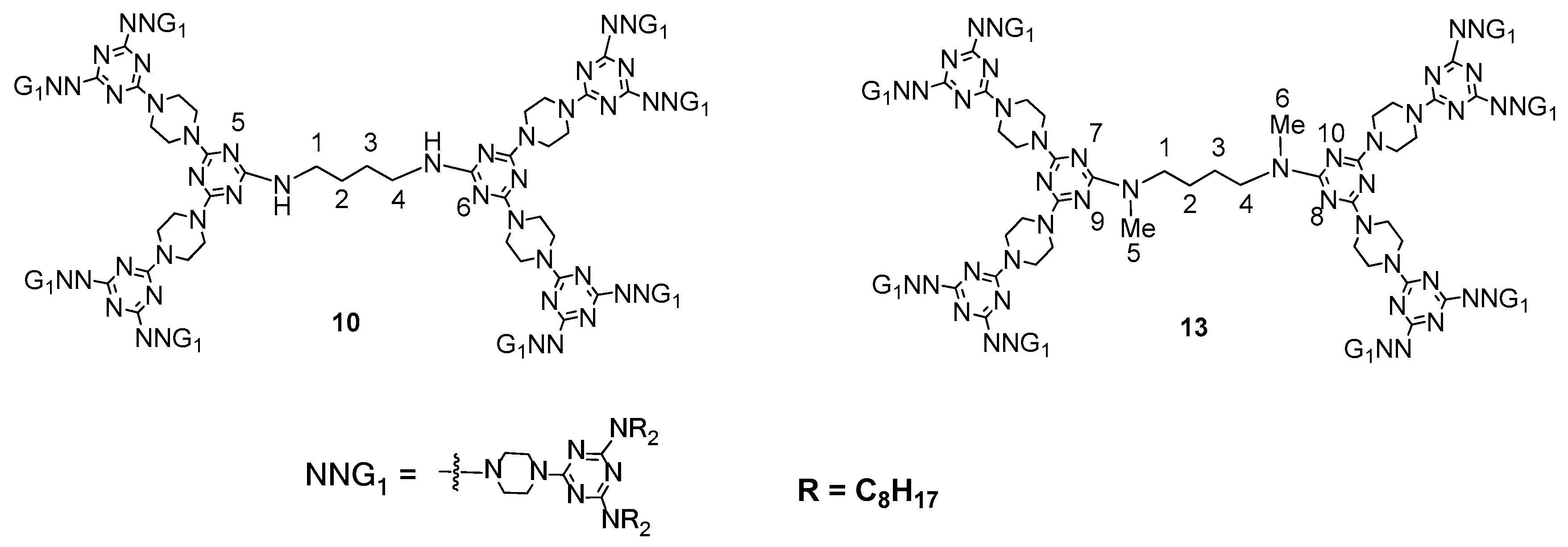

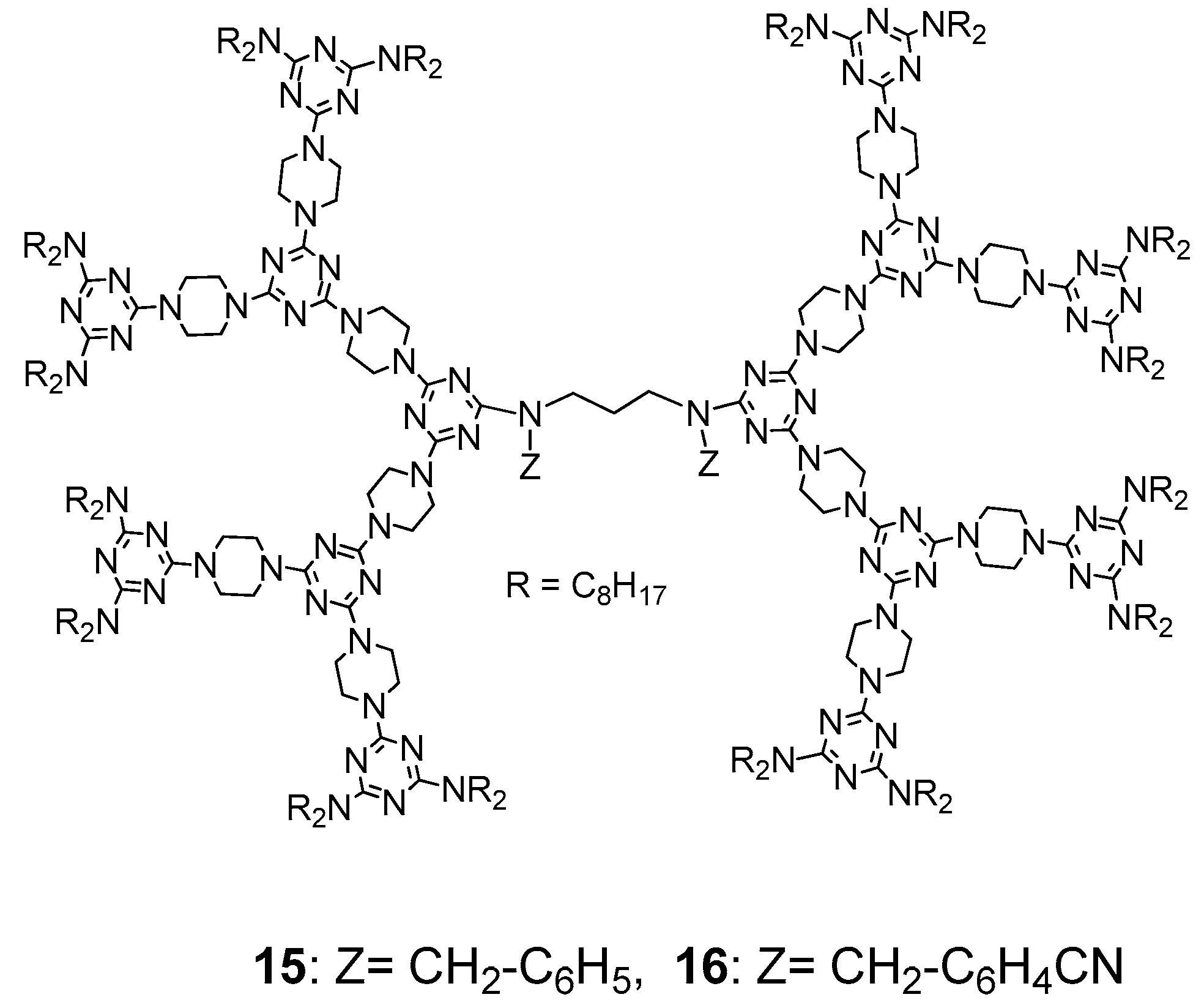

2.4. LC Dendrimers with the Loss of C2 Symmetry by Changing the Central Cores

3. Formation of Triazine-Based LC Dendrimers by Adding Extra Components

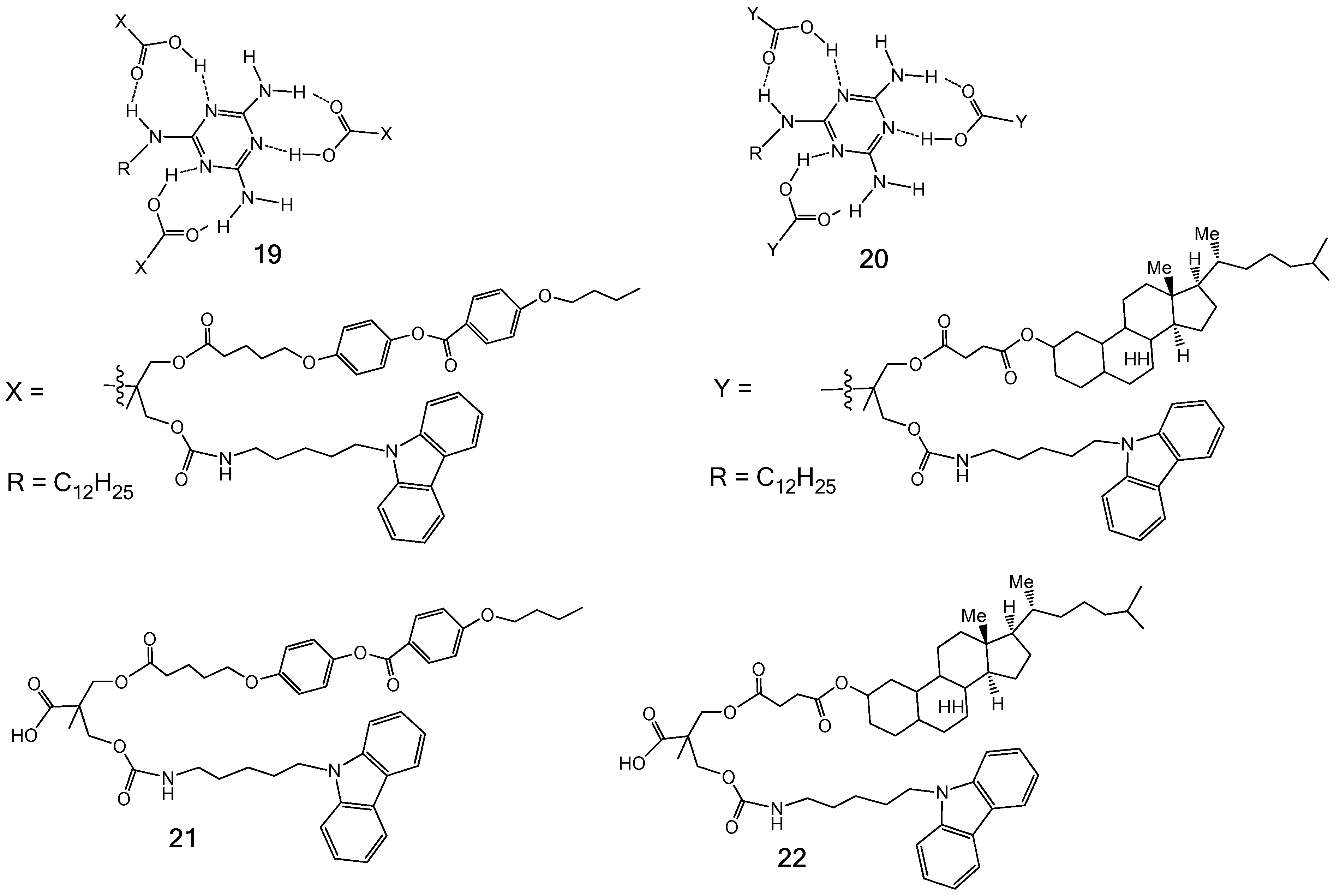

3.1. Formation of LC Dendrimers by Intermolecular π–π Interaction

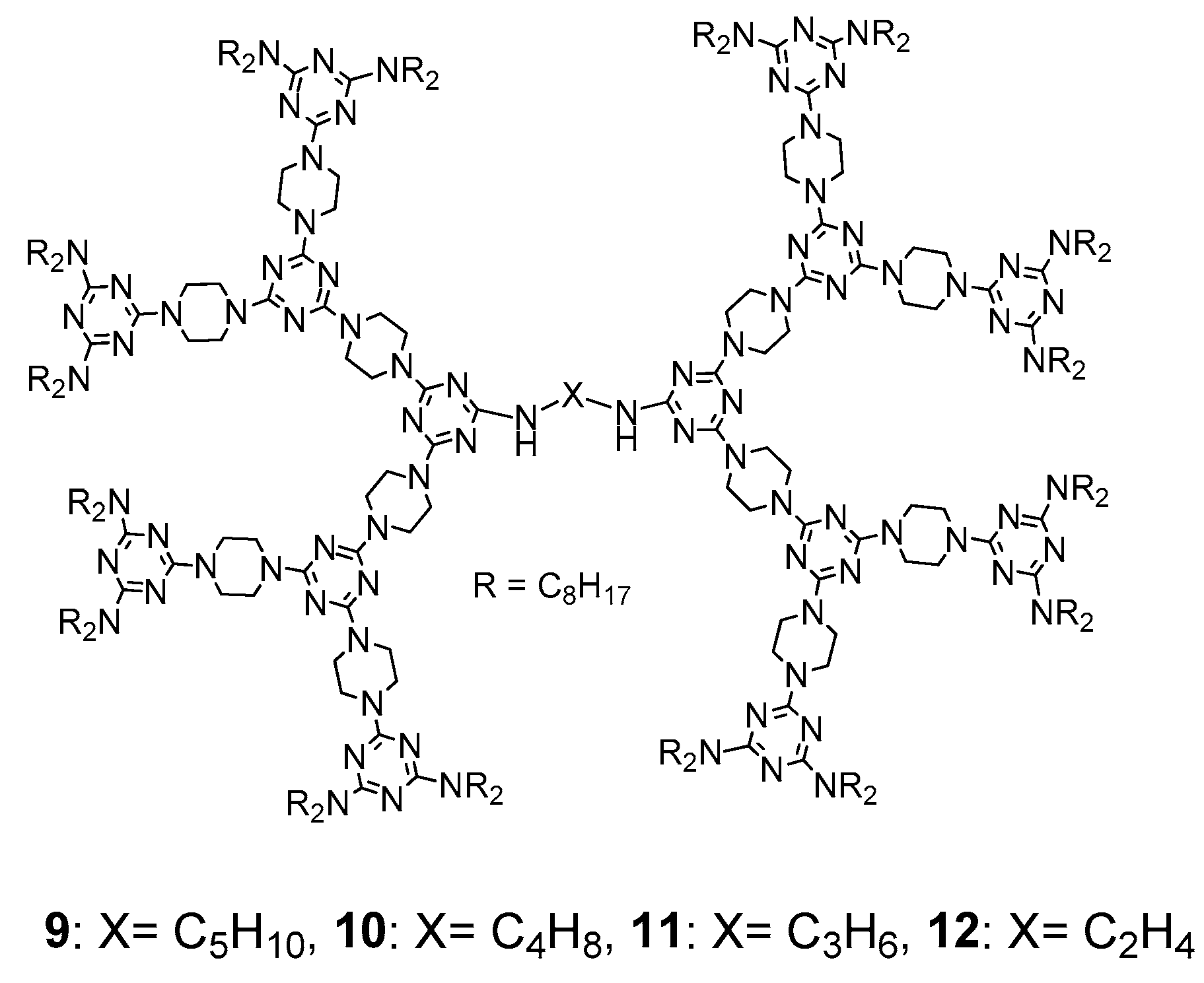

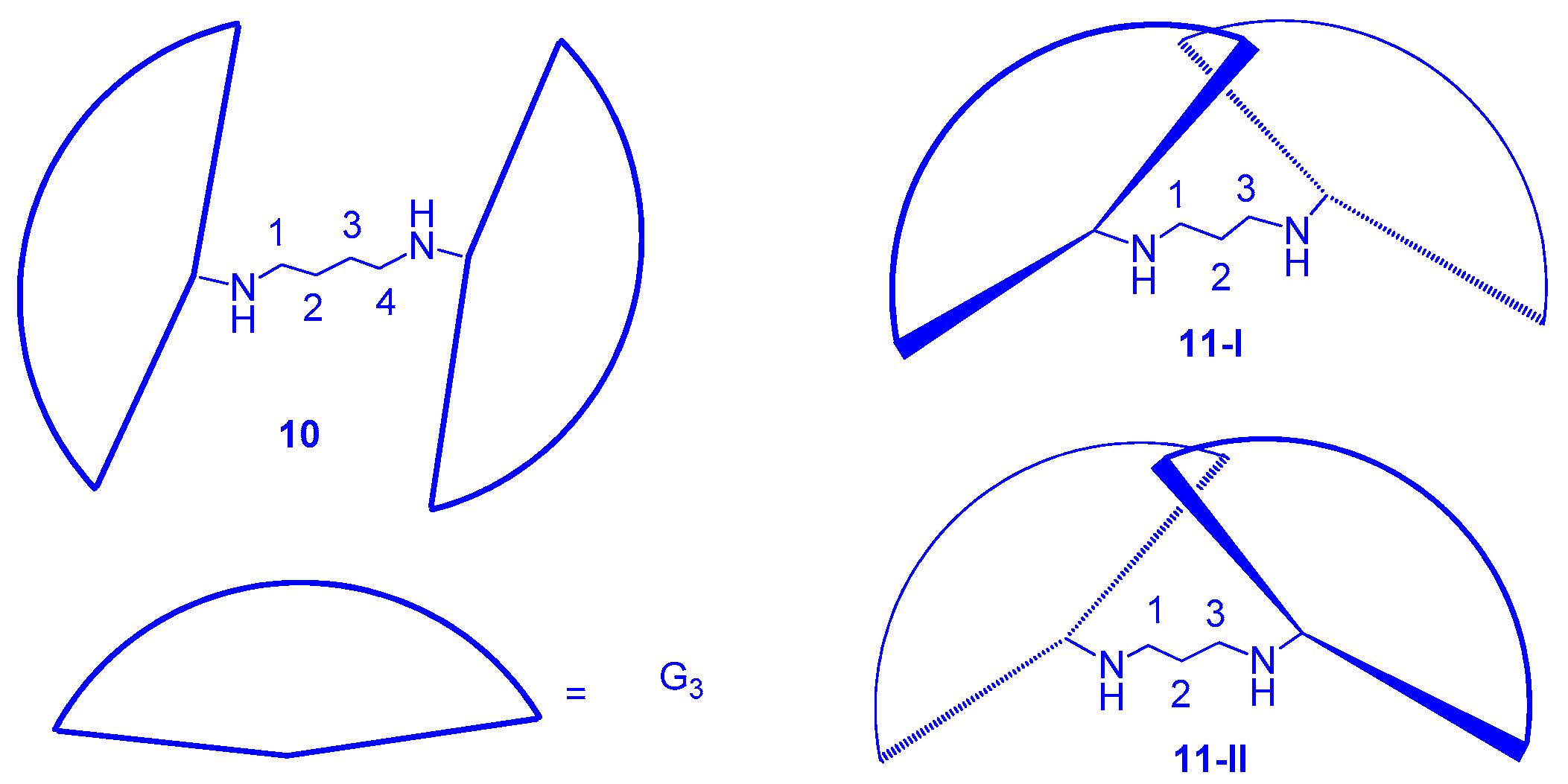

3.2. Formation of LC Dendrimers by Intermolecular H-Bond Interaction

4. Possible Applications

5. Conclusions and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomalia, D.A.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Discovery of dendrimers and dendritic polymers: A brief historical perspective. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 2719–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, A.-M.; Turrin, C.-O.; Laurent, R.; Ouali, A.; Delavaux-Nicot, B. Dendrimers: Towards Catalytic, Material and Biomedical Uses; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janaszewska, A.; Lazniewska, J.; Trzepiński, P.; Marcinkowska, M.; Klajnert-Maculewicz, B. Cytotoxicity of Dendrimers. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chauhan, A.S. Dendrimers for Drug Delivery. Molecules 2018, 23, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherje, A.P.; Jadhav, M.; Dravyakar, B.R.; Kadam, D. Dendrimers: A versatile nanocarrier for drug delivery and targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 548, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Jain, K.; Mehra, N.K.; Kesharwani, P.; Jain, N.K. A review on comparative study of PPI and PAMAM dendrimers. J. Nanopart. Res. 2016, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P.; Jain, K.; Jain, N.K. Dendrimer as nanocarrier for drug delivery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 268–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, K.; Kumar, S.; Poonia, N.; Lather, V.; Pandita, D. Dendrimers in drug delivery and targeting: Drug-dendrimer interactions and toxicity issues. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2014, 6, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mignani, S.; El Kazzouli, S.; Bousmina, M.; Majoral, J.-P. Expand classical drug administration ways by emerging routes using dendrimer drug delivery systems: A concise overview. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1316–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lopes, R.P.; Lüdtke, T.; Di Silvio, D.; Moya, S.; Hamon, J.-R.; Astruc, D. “Click” dendrimer-Pd nanoparticle assemblies as enzyme mimics: Catalytic o-phenylenediamine oxidation and application in colorimetric H2O2 detection. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 3301–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Imaoka, T.; Tanabe, M.; Kambe, T. New Horizon of Nanoparticle and Cluster Catalysis with Dendrimers. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 1397–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-H.; Cangiotti, M.; Kao, C.-L.; Ottaviani, M.F. EPR Characterization of Copper(II) Complexes of PAMAM-Py Dendrimers for Biocatalysis in the Absence and Presence of Reducing Agents and a Spin Trap. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 10498–10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Dib, H.; Caminade, A.-M.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Redox Control of a Dendritic Ferrocenyl-Based Homogeneous Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twyman, L.J.; King, A.S.H.; Martin, I.K. Catalysis inside dendrimers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astruc, D.; Chardac, F. Dendritic Catalysts and Dendrimers in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2991–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, R.M.; Zhao, M.; Sun, L.; Chechik, V.; Yeung, L.K. Dendrimer-Encapsulated Metal Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications to Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Concellón, A.; Termine, R.; Golemme, A.; Romero, P.; Marcos, M.; Serrano, J.L. High hole mobility and light-harvesting in discotic nematic dendrimers prepared via ‘click’ chemistry. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 2911–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, D.; Sung, J.; Kim, S.; Oh, J.; Yoon, H.; Sung, Y.M.; Kim, D.; Jang, W.-D. Guest-Induced Modulation of the Energy Transfer Process in Porphyrin-Based Artificial Light Harvesting Dendrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nantalaksakul, A.; Reddy, D.R.; Bardeen, C.J.; Thayumanavan, S. Light Harvesting Dendrimers. Photosyn. Res. 2006, 87, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani, V.; Ceroni, P.; Maestri, M.; Vicinelli, V. Light-harvesting dendrimers. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003, 7, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adronov, A.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Light-harvesting dendrimers. Chem. Comm. 2000, 18, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilat, S.L.; Adronov, A.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Light Harvesting and Energy Transfer in Novel Convergently Constructed Dendrimers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, X.; Lu, Q. Polyamidoamine dendrimer functionalized cellulose nanocrystals for CO2 capture. Cellulose 2021, 28, 4241–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kadib, A.; Katir, N.; Bousmina, M.; Majoral, J.P. Dendrimer–Silica hybrid mesoporous materials. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorsi, L.; Lombardo, D.; Longo, A.; Proverbio, E.; Triolo, A. Dendrimer Template Directed Self-Assembly during Zeolite Formation. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Lunn, J.D.; Gonzalez, S.; Ristich, J.A.; Simanek, E.E.; Shantz, D.F. Engineering Nanospaces: OMS/Dendrimer Hybrids Possessing Controllable Chemistry and Porosity. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 2935–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesel, J.W.; Tilley, T.D. Dendrimers as Building Blocks for Nanostructured Materials: Micro- and Mesoporosity in Dendrimer-Based Xerogels. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, N.P.; Inostroza-Rivera, R.; Durán, B.; Molero, L.; Bonardd, S.; Ramírez, O.; Isaacs, M.; Díaz Díaz, D.; Leiva, A.; Saldías, C. Exploring the Effect of the Irradiation Time on Photosensitized Dendrimer-Based Nanoaggregates for Potential Applications in Light-Driven Water Photoreduction. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avila-Salas, F.; Pereira, A.; Rojas, M.A.; Saavedra-Torres, M.; Montecinos, R.; Bonardd, S.; Quezada, C.; Saldías, S.; Díaz Díaz, D.; Leiva, A.; et al. An experimental and theoretical comparative study of the entrapment and release of dexamethasone from micellar and vesicular aggregates of PAMAM-PCL dendrimers. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 93, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axenov, K.V.; Laschat, S. Thermotropic Ionic Liquid Crystals. Materials 2011, 4, 206–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B.M.; Wilson, C.J.; Wilson, D.A.; Peterca, M.; Imam, M.R.; Percec, V. Dendron-Mediated Self-Assembly, Disassembly, and Self-Organization of Complex Systems. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6275–6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodby, J.W.; Saez, I.M.; Cowling, S.J.; Görtz, V.; Draper, M.; Hall, A.W.; Sia, S.; Cosquer, G.; Lee, S.-E.; Raynes, E.P. Transmission and Amplification of Information and Properties in Nanostructured Liquid Crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2754–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Jung, E.-Y.; Jin, L.Y.; Lee, M. Solution Behavior of Dendrimer-Coated Rodlike Coordination Polymers. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 6066–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K. Functional dendrimers, hyperbranched and star polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000, 25, 453–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ainsa, S.; Barberá, J. Fluorinated liquid crystalline dendrimers. J. Fluor. Chem 2015, 177, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnio, B.; Buathong, S.; Bury, I.; Guillon, D. Liquid crystalline dendrimers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1495–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos, M.; Martín-Rapún, R.; Omenat, A.; Serrano, J.L. Highly congested liquid crystal structures: Dendrimers, dendrons, dendronized and hyperbranched polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1889–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, I.M.; Goodby, J.W. Supermolecular liquid crystals. J. Mater. Chem. 2005, 15, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschenaux, R.; Donnio, B.; Guillon, D. Liquid-crystalline fullerodendrimers. New J. Chem. 2007, 31, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehringer, L.; Bourgogne, C.; Guillon, D.; Donnio, B. Liquid-Crystalline Octopus Dendrimers: Block Molecules with Unusual Mesophase Morphologies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3856–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehringer, L.; Guillon, D.; Donnio, B. Liquid Crystalline Octopus: An Alternative Class of Mesomorphic Dendrimers. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5593–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.; Lehmann, M. Stilbenoid Dendrimers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesak, D.J.; Moore, J.S. Columnar Liquid Crystals from Shape-Persistent Dendritic Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1636–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-F.; Crandall, K.A.; Chu, P.; Percec, V.; Petschek, R.G.; Rosenblatt, C. Dendrimeric Liquid Crystals: Isotropic−Nematic Pretransitional Behavior. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 7813–7819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percec, V.; Chu, P.; Ungar, G.; Zhou, J. Rational Design of the First Nonspherical Dendrimer Which Displays Calamitic Nematic and Smectic Thermotropic Liquid Crystalline Phases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11441–11454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, K.; Lava, K.; Bielawski, C.W.; Binnemans, K. Ionic Liquid Crystals: Versatile Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4643–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnio, B. Liquid–crystalline metallodendrimers. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2014, 409, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Mizoshita, N.; Kishimoto, K. Functional Liquid-Crystalline Assemblies: Self-Organized Soft Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 38–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

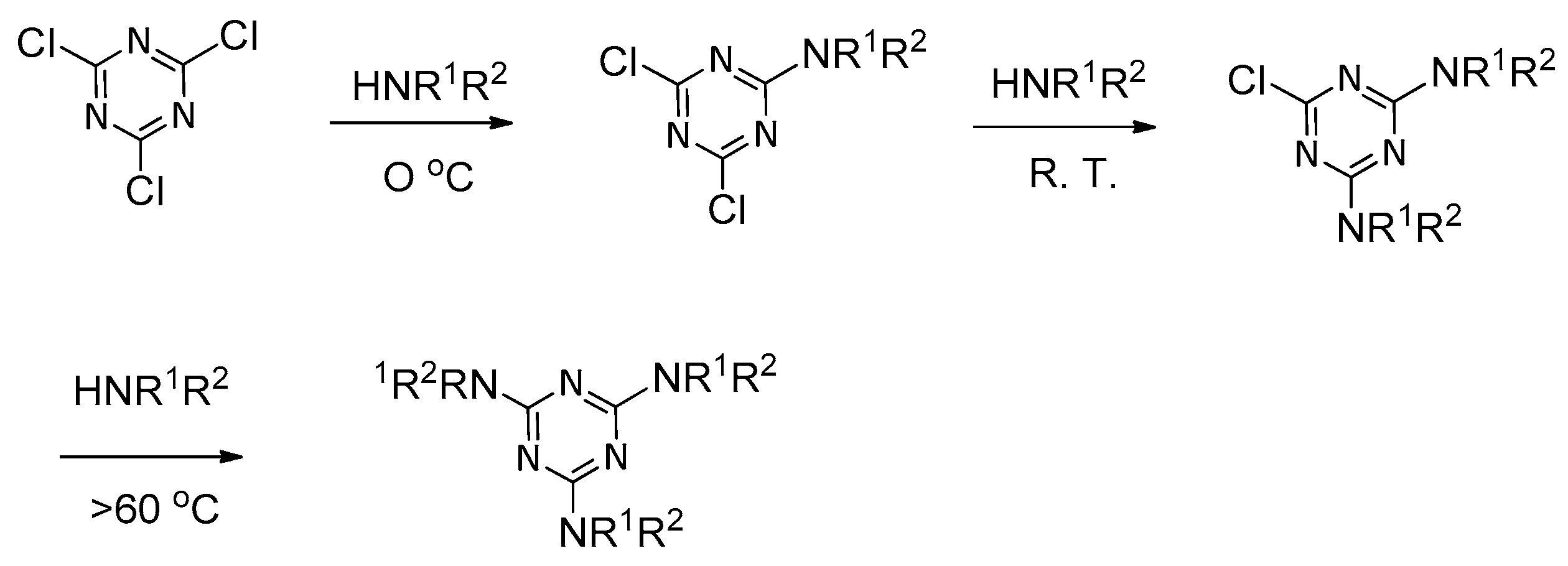

- Schnabel, W.J.; Rätz, R.; Kober, E. The Synthesis of Substituted Melams. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, J.T.; Dudley, J.R.; Kaiser, D.W.; Hechenbleikner, I.; Schaefer, F.C.; Holm-Hansen, D. Cyanuric Chloride Derivatives. I. Aminochloro-s-triazines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 2981–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, K.; Hattori, T.; Kunisada, H.; Yuki, Y. Triazine dendrimers by divergent and convergent methods. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 4385–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-L.; Wang, L.-Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Cheng, K.-L. Nanomaterials of Triazine-Based Dendrons: Convergent Synthesis and Their Physical Studies. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1541–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffensen, M.B.; Hollink, E.; Kuschel, F.; Bauer, M.; Simanek, E.E. Dendrimers based on [1,3,5]-triazines. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 3411–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, L.-L.; Lee, C.-H.; Wang, L.-Y.; Cheng, K.-L.; Hsu, H.-F. Star-Shaped Mesogens of Triazine-Based Dendrons and Dendrimers as Unconventional Columnar Liquid Crystals. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotha, S.; Kashinath, D.; Kumar, S. Synthesis of liquid crystalline materials based on 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene and 2,4,6-triphenyl-1,3,5-s-triazine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5419–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaut, O.; Bock, H.; Grelet, E. Face-on Oriented Bilayer of Two Discotic Columnar Liquid Crystals for Organic Donor−Acceptor Heterojunction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6886–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearman, G.C.; Yahioglu, G.; Kirstein, J.; Milgrom, L.R.; Seddon, J.M. Synthesis and phase behaviour of β-octaalkyl porphyrins. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-W.; Hsia, T.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Lai, C.-K.; Liu, R.-S. Synthesis and Columnar Mesophase of Fluorescent Liquid Crystals Bearing a C2-Symmetric Chiral Core. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4069–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhi, L.; Lucas, N.T.; Wang, Z. Triangle-shaped polycyclic aromatics based on tribenzocoronene: Facile synthesis and physical properties. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 3417–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-L.; Hsu, S.-J.; Hsu, H.-C.; Wang, S.-W.; Cheng, K.-L.; Chen, C.-J.; Wang, T.-H.; Hsu, H.-F. Formation of Columnar Liquid Crystals on the Basis of Unconventional Triazine-Based Dendrimers by the C3-Symmetric Approach. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6542–6547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfa Aesar. Research Chemicals, Metals and Materials; Alfa Aesar: Ward Hill, MA, USA, 2011; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.L.; Wang, S.W.; Cheng, K.L.; Lee, J.J.; Wang, T.H.; Hsu, H.F. Induction of the columnar phase of unconventional dendrimers by breaking the C2 symmetry of molecules. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 15361–15367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.-L.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Cheng, K.-L.; Liu, S.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Hsu, H.-F. A Small Change in Central Linker Has a Profound Effect in Inducing Columnar Phases of Triazine-Based Unconventional Dendrimers. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 5160–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-J.; Hsieh, J.-W.; Lai, L.-L.; Cheng, K.-L.; Liu, S.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Hsu, H.-F. Converting Nonliquid Crystals into Liquid Crystals by N-Methylation in the Central Linker of Triazine-Based Dendrimers. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 5007–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Lai, L.-L.; Lee, J.-J.; Hsu, H.-F. Both increasing the Iso-to-Col transition and lowering the solidifying temperatures of a triazine-based dendrimer by introducing CN polar groups in the dendritic core. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 14232–14238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelar, S.; Barberá, J.; Marcos, M.; Romero, P.; Serrano, J.-L.; Golemme, A.; Termine, R. Supramolecular dendrimers based on the self-assembly of carbazole-derived dendrons and triazine rings: Liquid crystal, photophysical and electrochemical properties. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 7321–7332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.-L.; Hsu, H.-C.; Hsu, S.-J.; Cheng, K.-L. A Convenient Synthesis of Triazine-Based Dendrons and Dendrimers via a Convergent Approach and a Study of Their Interactions with Tetrafluorobenzoquinone. Synthesis 2010, 2010, 3576–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y.-C.; Hsu, H.-F.; Lai, L.-L. Unconventional Approaches to Prepare Triazine-Based Liquid Crystal Dendrimers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11082112

Lu Y-C, Hsu H-F, Lai L-L. Unconventional Approaches to Prepare Triazine-Based Liquid Crystal Dendrimers. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(8):2112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11082112

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Yao-Chih, Hsiu-Fu Hsu, and Long-Li Lai. 2021. "Unconventional Approaches to Prepare Triazine-Based Liquid Crystal Dendrimers" Nanomaterials 11, no. 8: 2112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11082112

APA StyleLu, Y.-C., Hsu, H.-F., & Lai, L.-L. (2021). Unconventional Approaches to Prepare Triazine-Based Liquid Crystal Dendrimers. Nanomaterials, 11(8), 2112. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11082112