The Application of Nano-MoS2 Quantum Dots as Liquid Lubricant Additive for Tribological Behavior Improvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis of MoS2 QDs and Dispersion Process in Paroline Oil

2.2. Tribological Procedure of Ball-On-Disc Testing

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

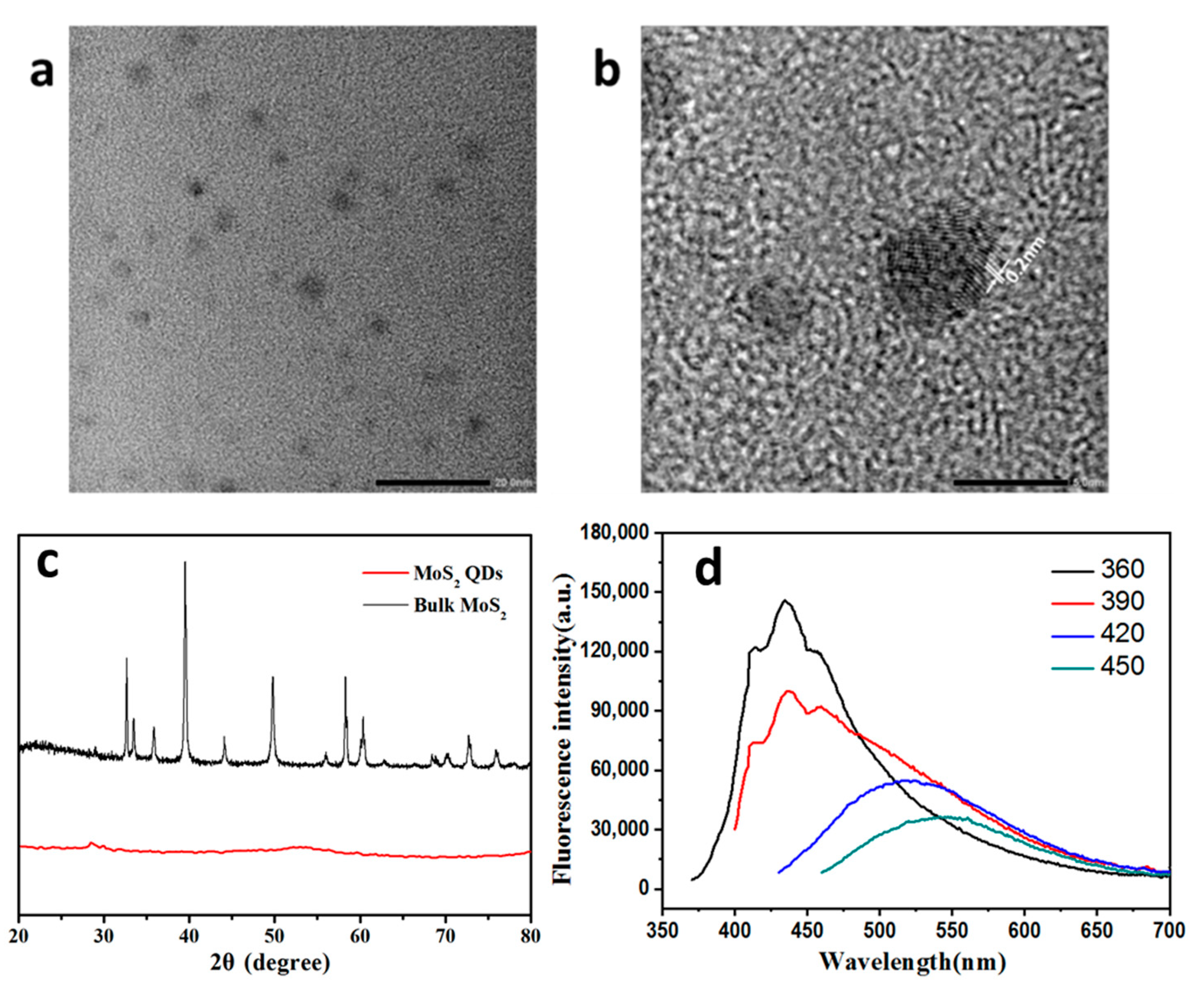

3.1. Characterization of MoS2 QDs

3.2. Friction Property of MoS2 QDs in Paroline Oil

3.3. Wear Scar Images of Balls and Discs

3.4. Lubrication Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ofune, M.D.; Banks, P.; Morina, A.; Neville, A. Development of valve train rig for assessment of cam/follower tribochemistry. Tribol. Int. 2016, 93, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Qin, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, G. An effective method of edge deburring for laser surface texturing of Co-Cr-Mo alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, H.W.; Peng, Z.X. The gearbox wears state monitoring and evaluation based on on-line wear debris features. Wear 2019, 426, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Feng, X.; Hafezi, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Dong, G.; Qin, Y. Investigating the tribological and biological performance of covalently grafted chitosan coatings on Co-Cr-Mo alloy. Tribol. Int. 2018, 127, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Mei, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, S.; Hafezi, M.; Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Dong, G. Sustained-release application of PCEC hydrogel on laser-textured surface lubrication. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 065315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, M.; Kogovšek, J.; Remškar, M. Nanoparticles as novel lubricating additives in a green, physically based lubrication technology for DLC coatings. Wear 2013, 303, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Johnson, B.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Dong, G. Investigation on the lubrication advantages of MoS2 nanosheets compared with ZDDP using block-on-ring tests. Wear 2018, 394–395, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matczak, L.; Johanning, C.; Gil, E.; Guo, H.; Smith, T.W.; Schertzer, M.; Iglesias, P. Effect of cation nature on the lubricating and physicochemical properties of three ionic liquids. Tribol. Int. 2018, 124, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengudusamy, B.; Green, J.H.; Lamb, G.D.; Spikes, H.A. Behaviour of MoDTC in DLC/DLC and DLC/steel contacts. Tribol. Int. 2012, 54, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, M.; Gili, F.; Mangherini, D.; Lahouij, I.; Dassenoy, F.; Garcia, I.; Odriozola, I.; Kraft, G. Friction reduction benefits in valve-train system using IF-MoS2 added engine oil. Tribol. Trans. 2015, 58, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, L.; Luo, J. An investigation on the tribological properties of multilayer graphene and MoS2 nanosheets as additives used in hydraulic applications. Tribol. Int. 2016, 97, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luster, B.; Church, A.; Muratore, C.; Voevodin, A.A.; Kohli, P.; Aouadi, S.; Talapatra, S. Carbon nanotube—MoS2 composites as solid lubricants. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2009, 1, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaso, P.; Ville, F.; Dassenoy, F.; Diaby, M.; Afanasiev, P.; Cavoret, J.; Vacher, B.; Le Mogne, T. Boundary lubrication: Influence of the size and structure of inorganic fullerene-like MoS2 nanoparticles on friction and wear reduction. Wear 2014, 320, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershin, V.; Ovchinnikov, K.; Alsilo, A.; Stolyarov, R.; Memetov, N. Development of Environmentally Safe Lubricants Modified by Grapheme. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2018, 13, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Gunsel, S.; Luo, J. Ultrathin MoS2 nanosheets with superior extreme pressure property as boundary lubricants. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, Y.; Tian, P.; Guo, F.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, W.; Ji, X.; Liu, J. Soluble, exfoliated two-dimensional nanosheets as excellent aqueous lubricants. Acs Appl. Mater. Int. 2016, 8, 32440–32449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldana, P.U.; Dassenoy, F.; Vacher, B.; Le Mogne, T.; Thiebaut, B. WS2 nanoparticles anti-wear and friction reducing properties on rough surfaces in the presence of ZDDP additive. Tribol. Int. 2016, 102, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawbake, A.S.; Waykar, R.G.; Late, D.J.; Jadkar, S.R. Highly Transparent Wafer-Scale Synthesis of Crystalline WS2 Nanoparticle Thin Film for Photodetector and Humidity-Sensing Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 2016, 8, 3359–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, D.; Damien, D.; Shaijumon, M.M. MoS2 quantum dot-interspersed exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5297–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ding, C.; Xian, Y. One-step synthesis of water-soluble MoS2 quantum dots via a hydrothermal method as a fluorescent probe for hyaluronidase detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 2016, 8, 11272–11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, D.; Wu, P. One-Pot, Facile, and Versatile Synthesis of Monolayer MoS2/WS2 Quantum Dots as Bioimaging Probes and Efficient Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Fan, J.Y.; Qiu, T.; Yang, X.; Siu, G.G.; Chu, P.K. Experimental evidence for the quantum confinement effect in 3C-SiC nanocrystallites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 026102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štengl, V.; Henych, J. Strongly luminescent monolayered MoS2 prepared by effective ultrasound exfoliation. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjie, M.; Junde, G.; Zhe, T.; Qiang, M.; Guangneng, D. Effects of Sliding Mode on Tribological Properties of Lubricating Oil with Surface-Modificated MoS2 Nanosheets and the Mechanism. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2019, 53, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Johnson, B.; Wang, L.; Dong, G.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J. High-efficiency preparation of oil-dispersible MoS2 nanosheets with superior anti-wear property in ultralow concentration. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2017, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannous, J.; Lahouij, I.; Mogne, T.L.; Vacher, B.; Bruhács, A.; Tremel, W. Understanding the Tribochemical Mechanisms of IF-MoS2 Nanoparticles Under Boundary Lubrication. Tribol. Lett. 2011, 41, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouij, I.; Bucholz, E.W.; Vacher, B.; Sinnott, S.B.; Martin, J.M.; Dassenoy, F. Lubrication mechanisms of hollow-core inorganic fullerene-like nanoparticles: Coupling experimental and computational works. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 375701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.L.; Li, D.X.; Si, G.J.; Deng, X. Investigation of the influence of solid lubricants on the tribological properties of polyamide 6 nanocomposite. Wear 2014, 311, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Zhang, C. The synthesis of MoS2 particles with different morphologies for tribological applications. Tribol. Int. 2017, 116, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jian, G.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yu, J.; Hu, X. Lubricating mechanism of Fe3O4@MoS2 core-shell nanocomposites as oil additives for steel/steel contact. Tribol. Int. 2018, 121, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Mei, T.; Li, Y.; Hafezi, M.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Dong, G. One-pot synthesis and lubricity of fluorescent carbon dots applied on PCL-PEG-PCL hydrogel. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2018, 29, 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, J.; Peng, R.; Du, H.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Dong, G. The Application of Nano-MoS2 Quantum Dots as Liquid Lubricant Additive for Tribological Behavior Improvement. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020200

Guo J, Peng R, Du H, Shen Y, Li Y, Li J, Dong G. The Application of Nano-MoS2 Quantum Dots as Liquid Lubricant Additive for Tribological Behavior Improvement. Nanomaterials. 2020; 10(2):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020200

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Junde, Runling Peng, Hang Du, Yunbo Shen, Yue Li, Jianhui Li, and Guangneng Dong. 2020. "The Application of Nano-MoS2 Quantum Dots as Liquid Lubricant Additive for Tribological Behavior Improvement" Nanomaterials 10, no. 2: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020200

APA StyleGuo, J., Peng, R., Du, H., Shen, Y., Li, Y., Li, J., & Dong, G. (2020). The Application of Nano-MoS2 Quantum Dots as Liquid Lubricant Additive for Tribological Behavior Improvement. Nanomaterials, 10(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020200