From Single-Core Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids to Multi-Core Magnetic Nanocomposites: Assembly Strategies, Structure, and Magnetic Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Multi-Core Superparamagnetic Nanospheres and Microspheres

2.1. Emulsion Procedures

2.2. Induced Destabilization of a Ferrofluid

2.3. Magnetoliposomes

2.4. Co-Assembling in Aqueous Solution

3. Non-Spherical Multi-Core Superparamagnetic Assemblies

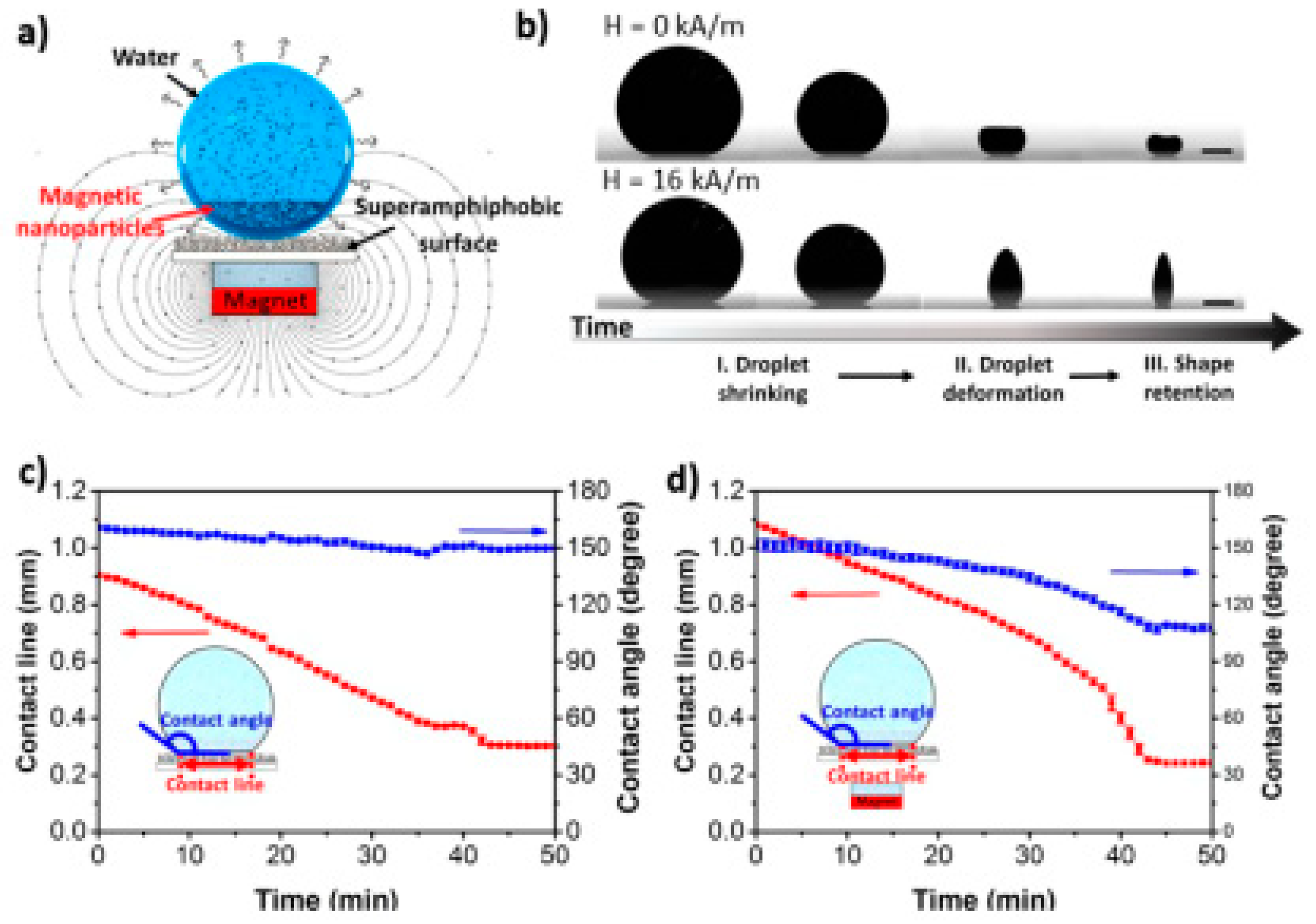

3.1. Evaporation-Guided Self-Assembly

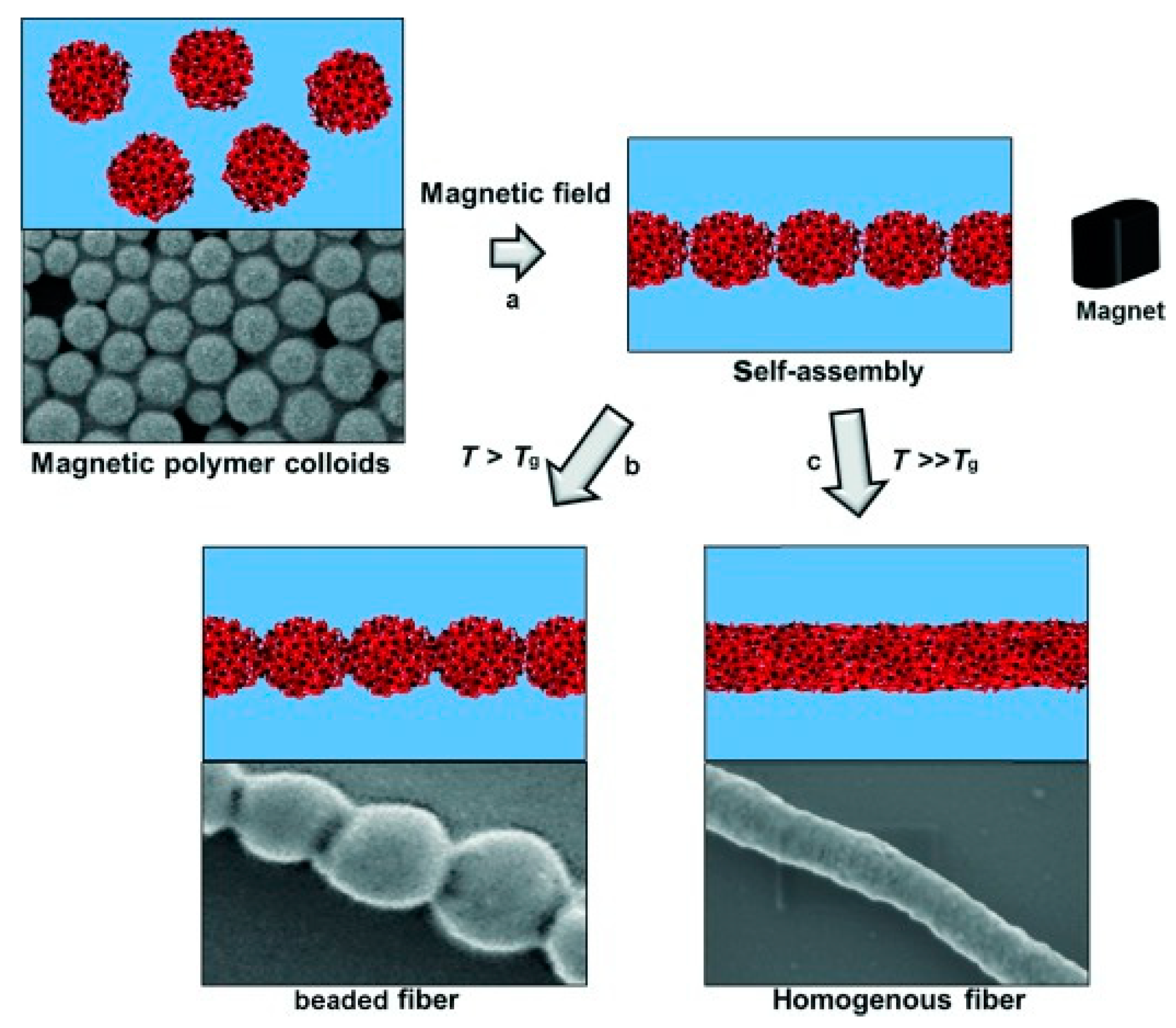

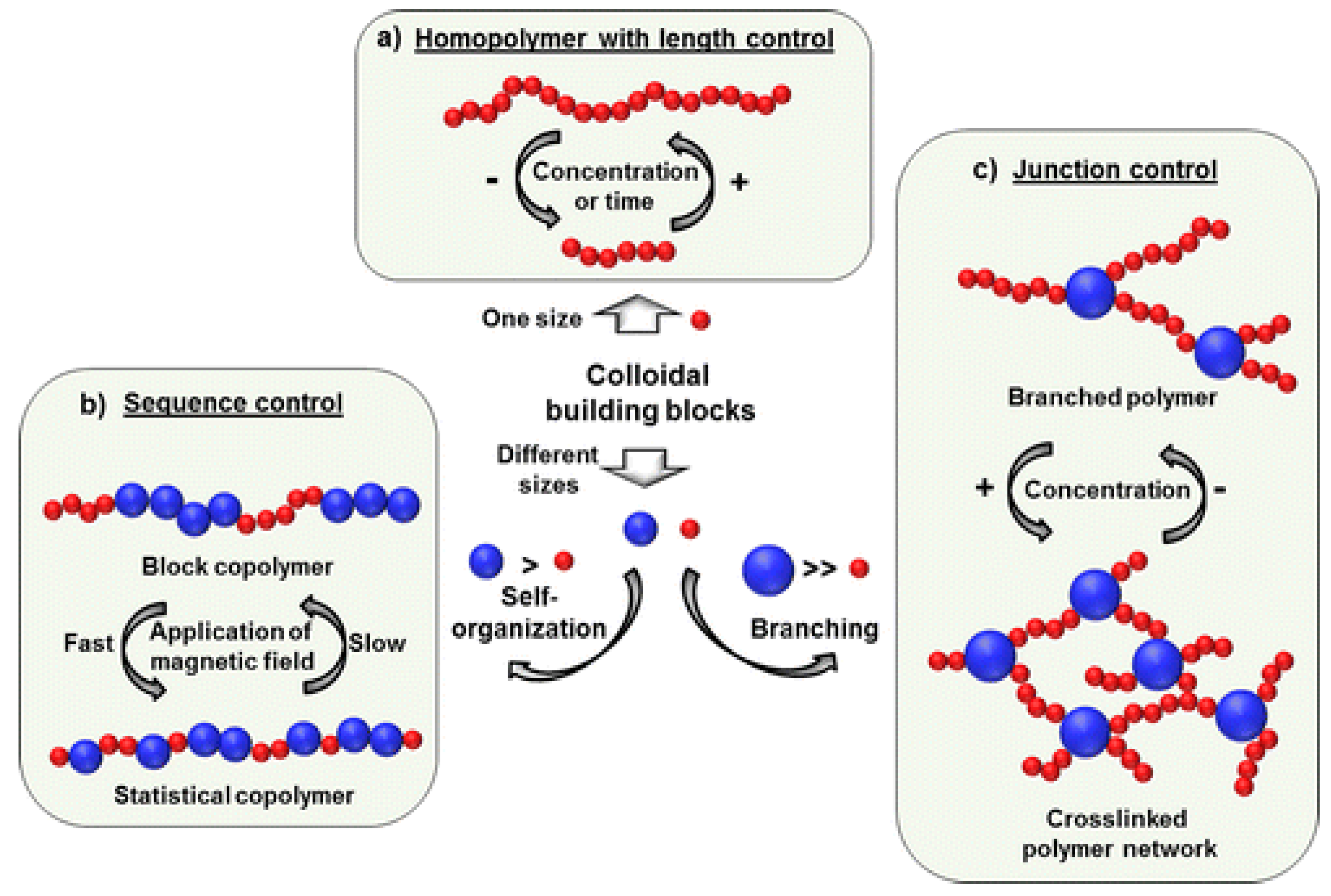

3.2. Magnetic Field-Assisted Self-Assembly

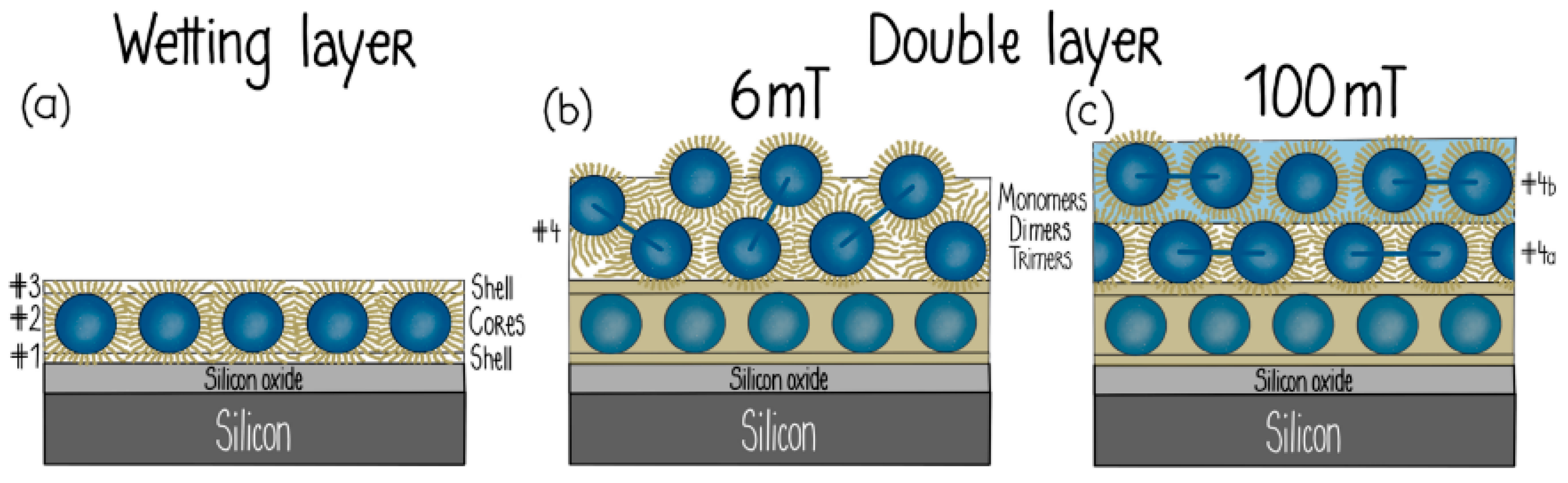

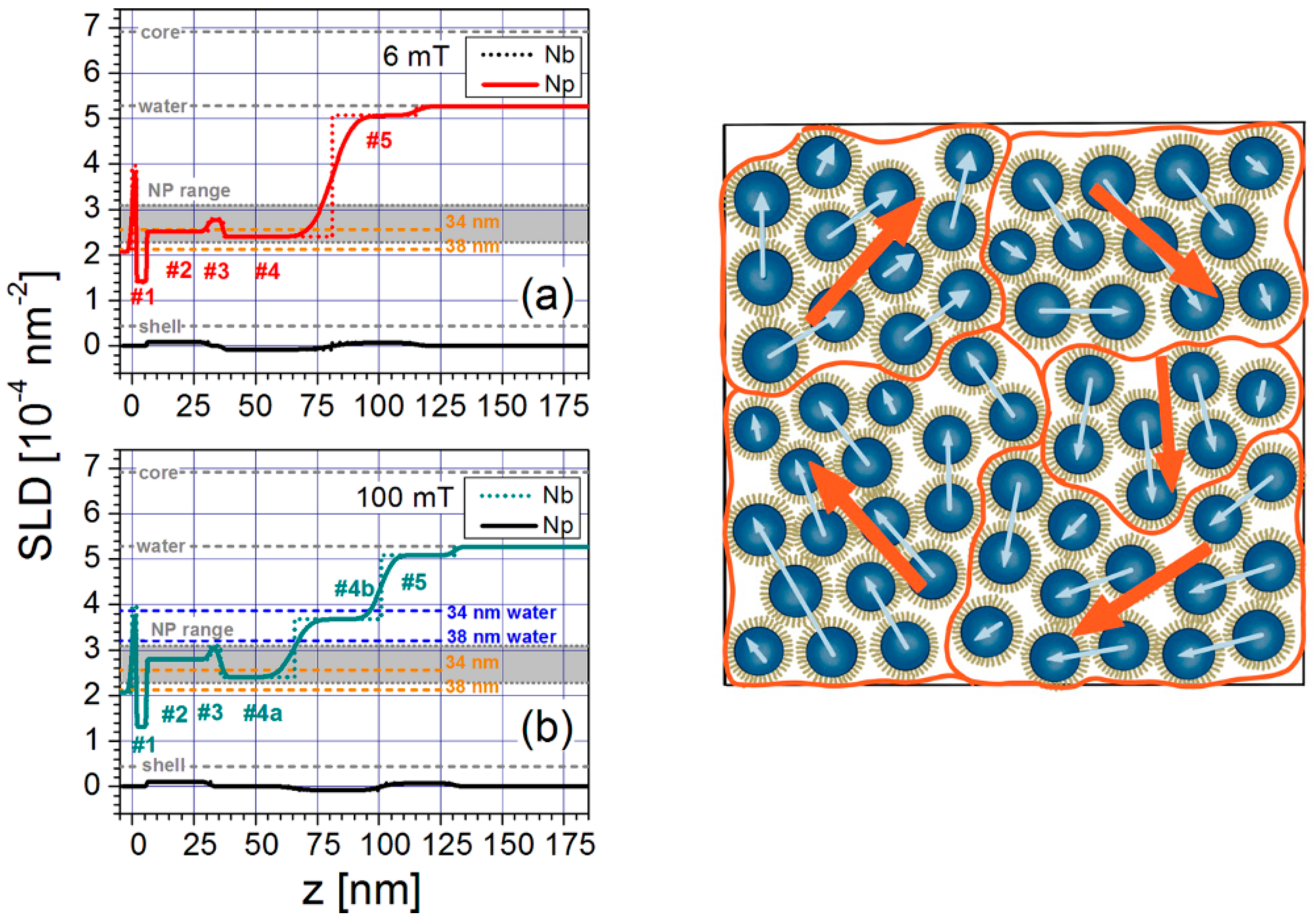

3.3. Magnetic Nanoparticle Assemblies on Surfaces

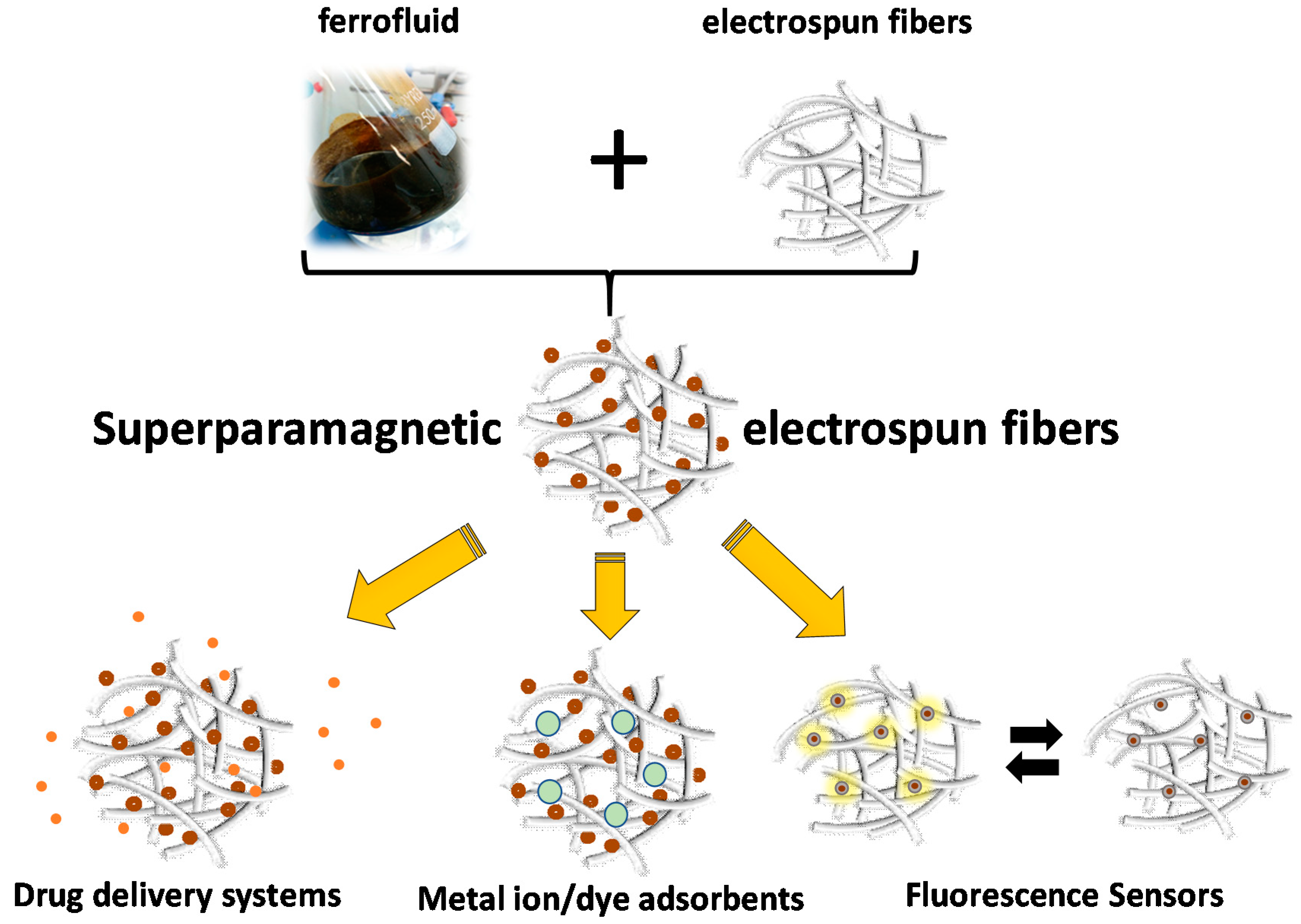

3.4. Electrospinning

3.5. Supramolecular Approaches

3.6. Ink-Jet Printing and Lithography-Based Approaches

| Multi-Core Magnetic Particles | Primary Single-Core IONP | Preparation Method | Mean Size (nm) | Msat (emu/g) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical particles | |||||

| MCIO/CMD | - | modified alkaline precipitation method | 40–80 a | - | [63,84] |

| MCIO/CTAB; MCIO/PEI; MCIO/PAA | Fe3O4/OA-Oam in hexane | emulsion | 30–88 a | 60 | [122] |

| MCIO/SDS | IONP/fatty acid (commercial product) | emulsion | 40–200 a | 62 | [123] |

| MCIO/SDS/hydrogel poly(NIPAM-AA) | IONP/fatty acid (commercial product) | emulsion/precipitation polymerization | 64 a; 80 b | - | [124] |

| MCIO/PEG-AA | Fe3O4/OA in hexane(ferrofluid) | emulsion-templated | 430–660 a | 7.5–24.8 | [120] |

| MCIO/PEI/PAAMA | Fe3O4/OA in hexane (ferrofluid) | emulsion | ≈1200 a | - | [125] |

| MCIO/SDS-Tween 85; MCIO/CTAB-Tween 85; MCIO/Pluronic PE 6800 | Fe3O4/OA in octane (ferrofluid) | emulsion | 50–300 a | 57 | [93] |

| MCIO/PBMA-g-C12 | MnFe2O4/OA | emulsion | 80 a | 11–32 | [182] |

| MCIO in soybean, corn, cottonseed, olive oil or MCT/PEG-DSPE | Fe3O4/OA in toluene (ferrofluid) | emulsion | 30–95 b | - | [217,218] |

| MCIO/SDS/PAA MCIO/SDS/PNIPAM-PAA | Fe3O4/OA Toluene ferrofluid | emulsion/radical polymerization | 100–200 a | 43–46.8 | [127] |

| Silica-coated magnetic nanocapsules (SiMNCs) | Fe3O4/OA in octane ferrofluid | emulsion/silica coated of Fe3O4-polystyrene nanospheres/polystyrene burned | 100 a | 45 | [219] |

| MCIO/Protoporphyrin IX; | Hydrophobic SPIONs in toluene | emulsion | 37 b | - | [130] |

| MCIO/chlorin e6 | Fe3O4/OA in toluene (ferrofluid) | emulsion | 96.38 ± 4.6 b | - | [135] |

| magnetoresponsive supraparticles (SPs) | CoFe2O4/OA in cyclohexane (ferrofluid) | emulsion | 105–734 a | - | [138] |

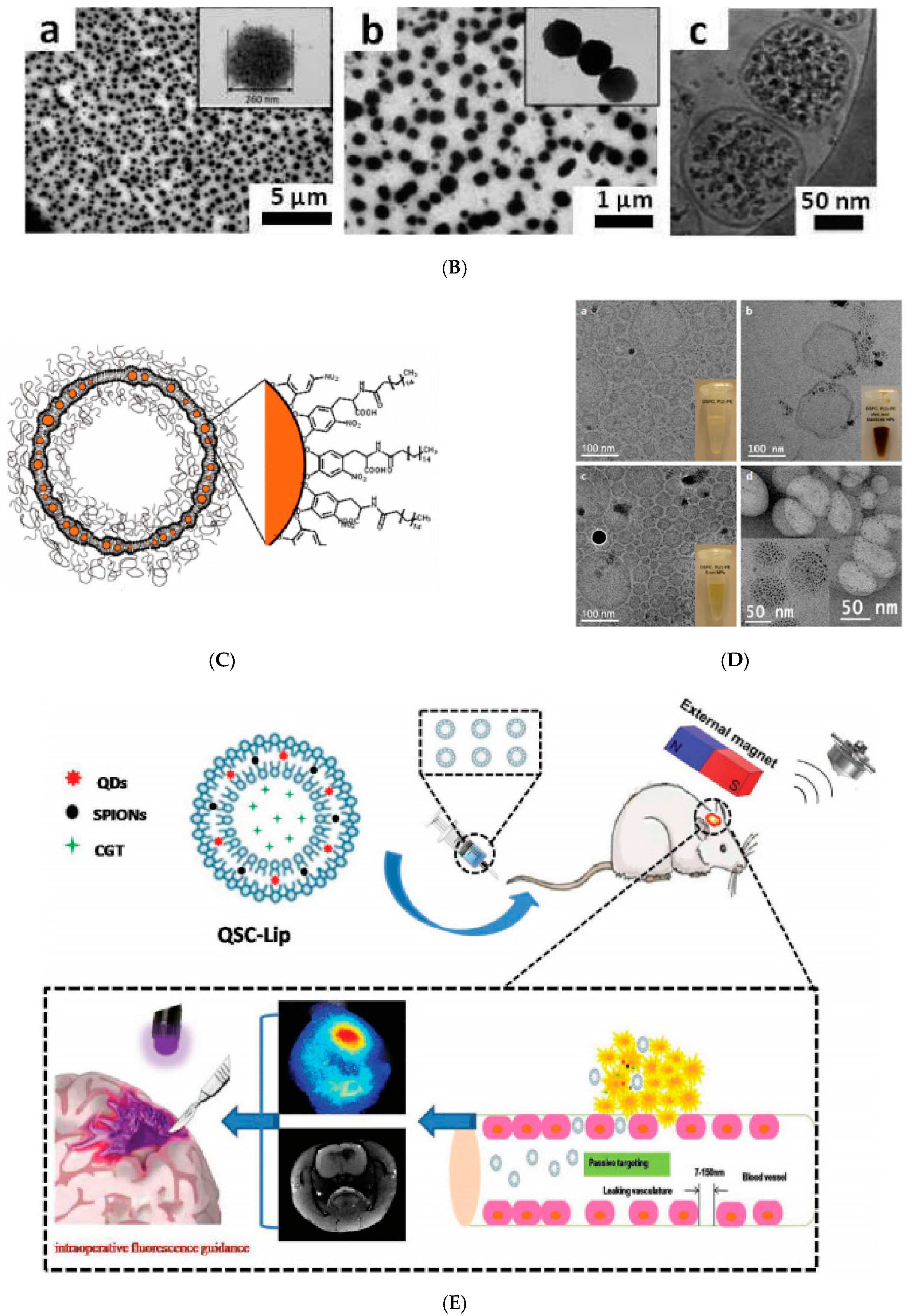

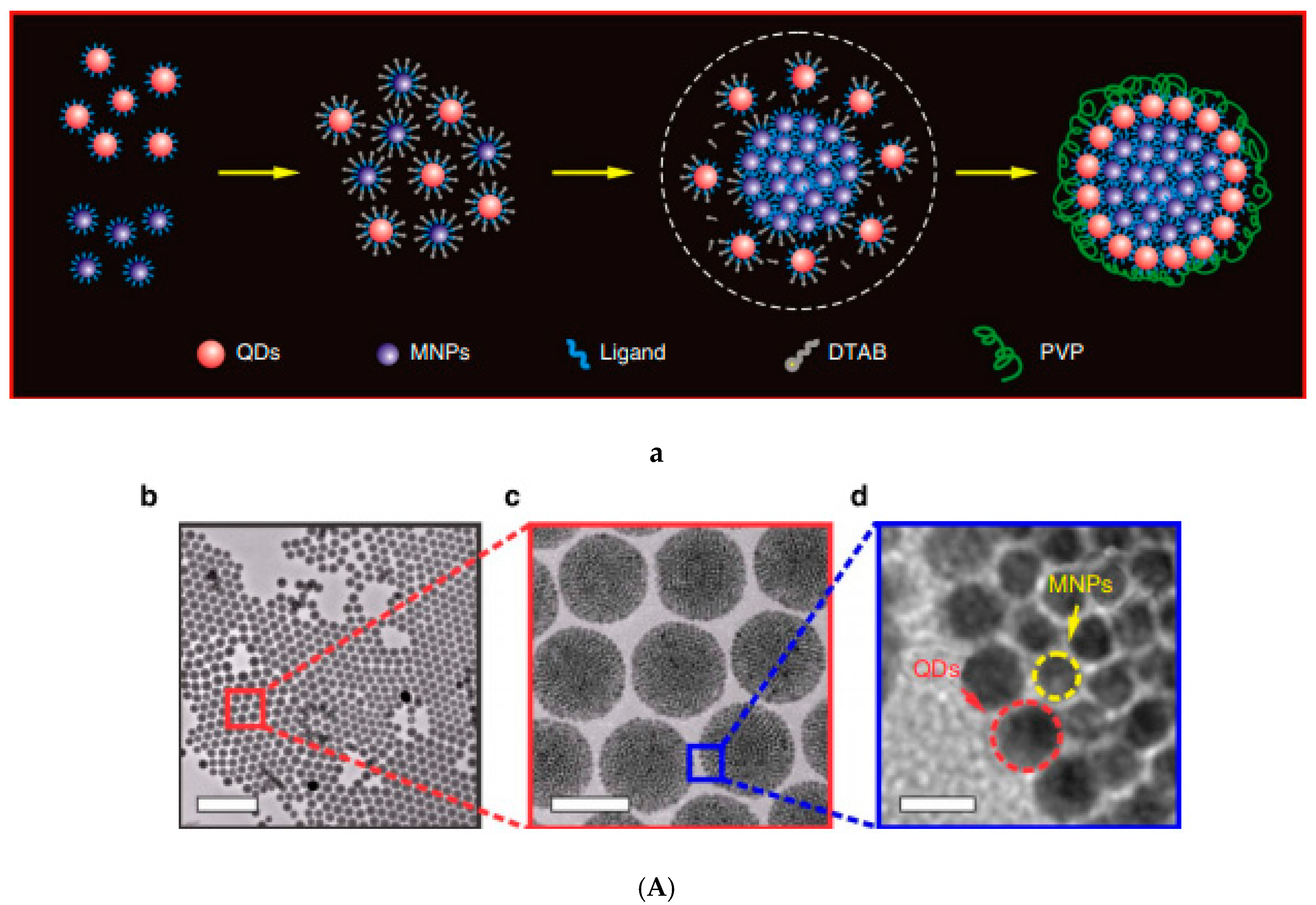

| SPs/DTAB/CdSe-CdS (QDs) | Fe3O4 in chloroform ferrofluid | emulsion | 120 a | 15.2 | [144] |

| MCIO/PLGA/ PbS(QDs) | Fe3O4/OA in hexane (ferrofluid) | double emulsion | 100 nm–1 µm a | 55 | [145] |

| MCIO/PS-b-PAA/pyrene/PVA | Hydrophobic SPIONs in chloroform | emulsion | 180 a | - | [141] |

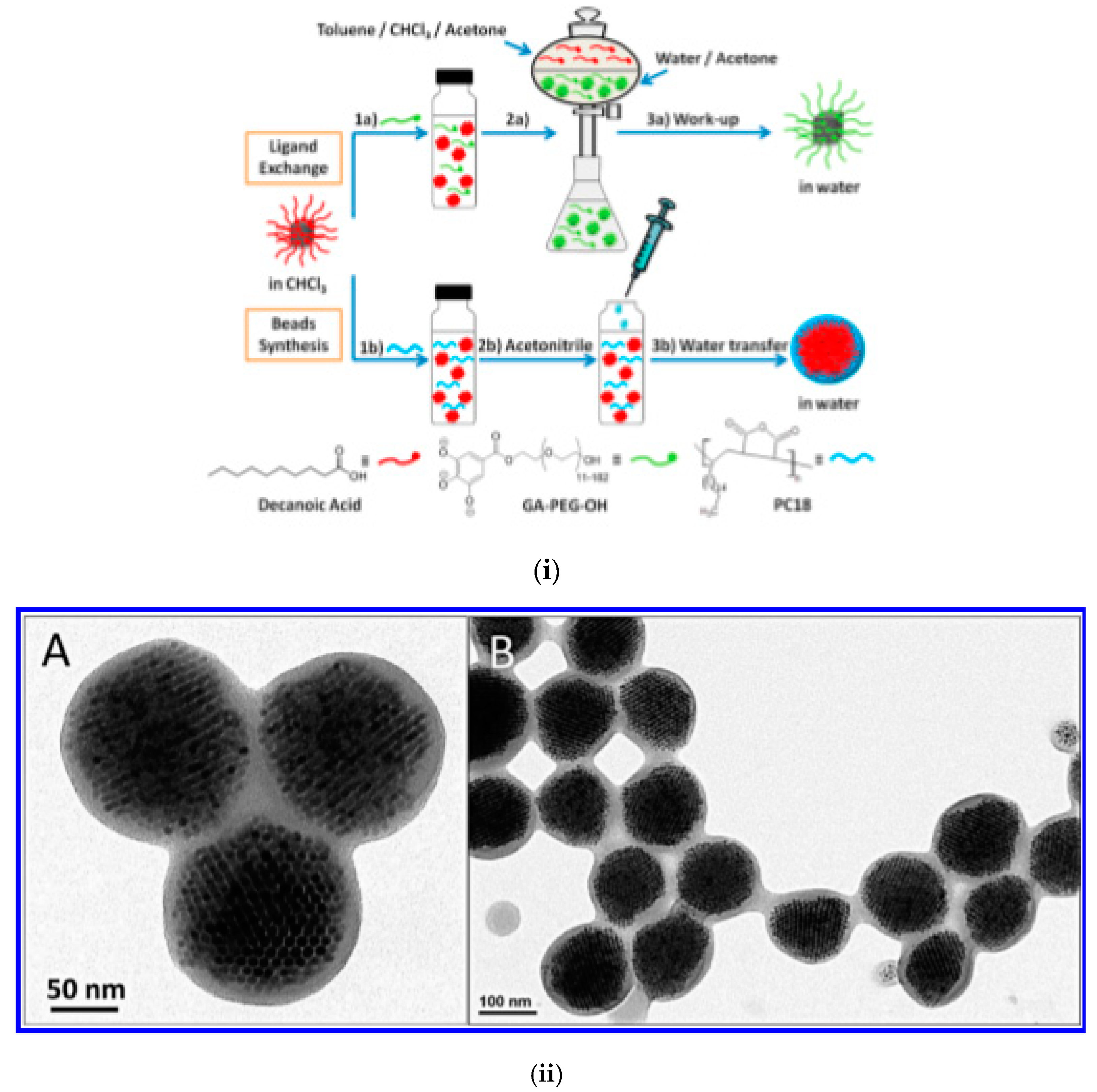

| MCIO/GA-PEG-OH | Hydrophobic IONP (ferrofluid) | induced destabilization of ferrofluid | 173 b | 60 | [148] |

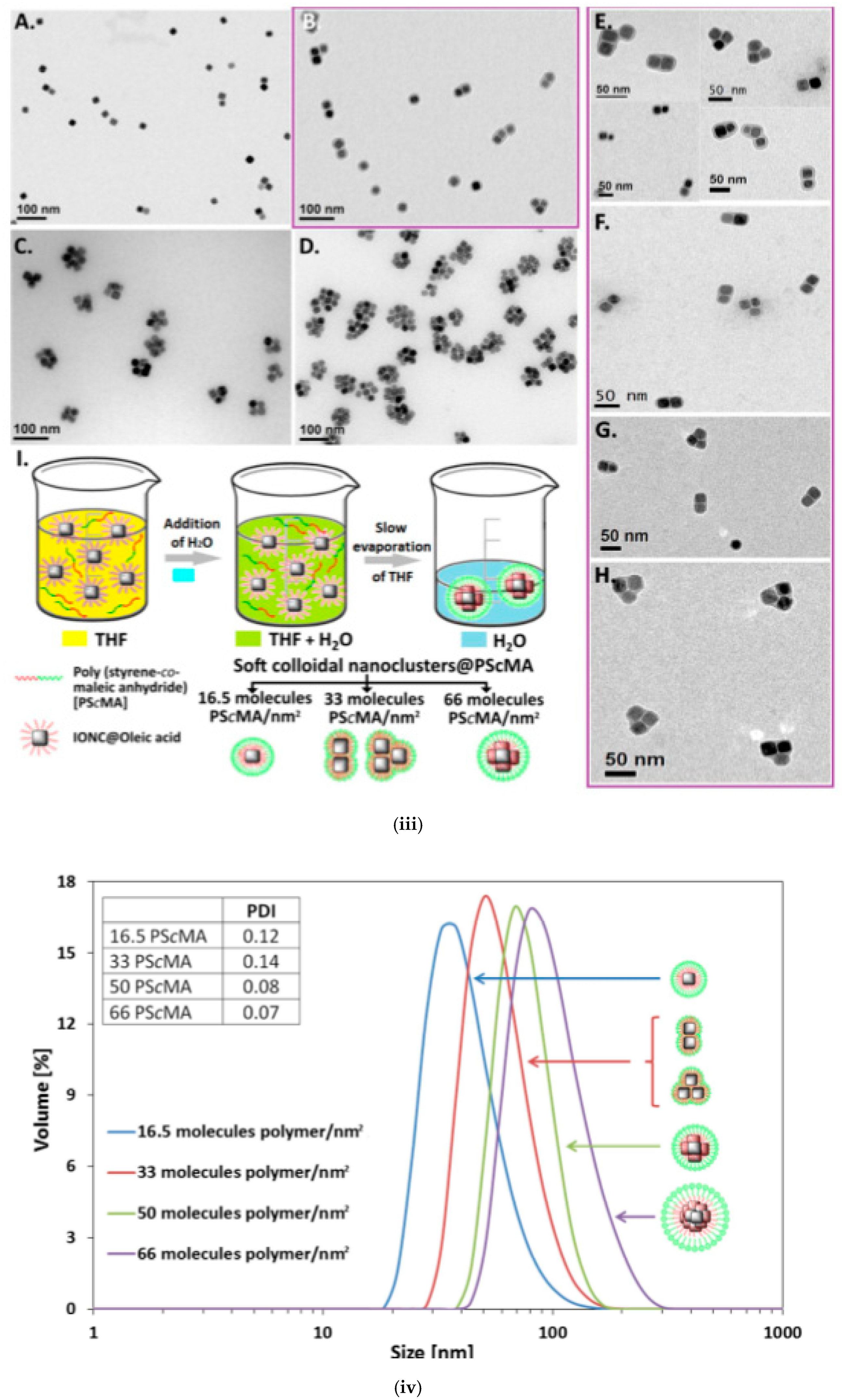

| MCIO/PScMA | IONP/OA in THF (ferrofluid) | induced destabilization of ferrofluid | 38–99 b | 314–407 emu/cm3 | [149] |

| Magnetic liposomes | IONP/OA in chloroform (ferrofluid) | coating of IONP with lipid shells | 115–401 a | - | [158] |

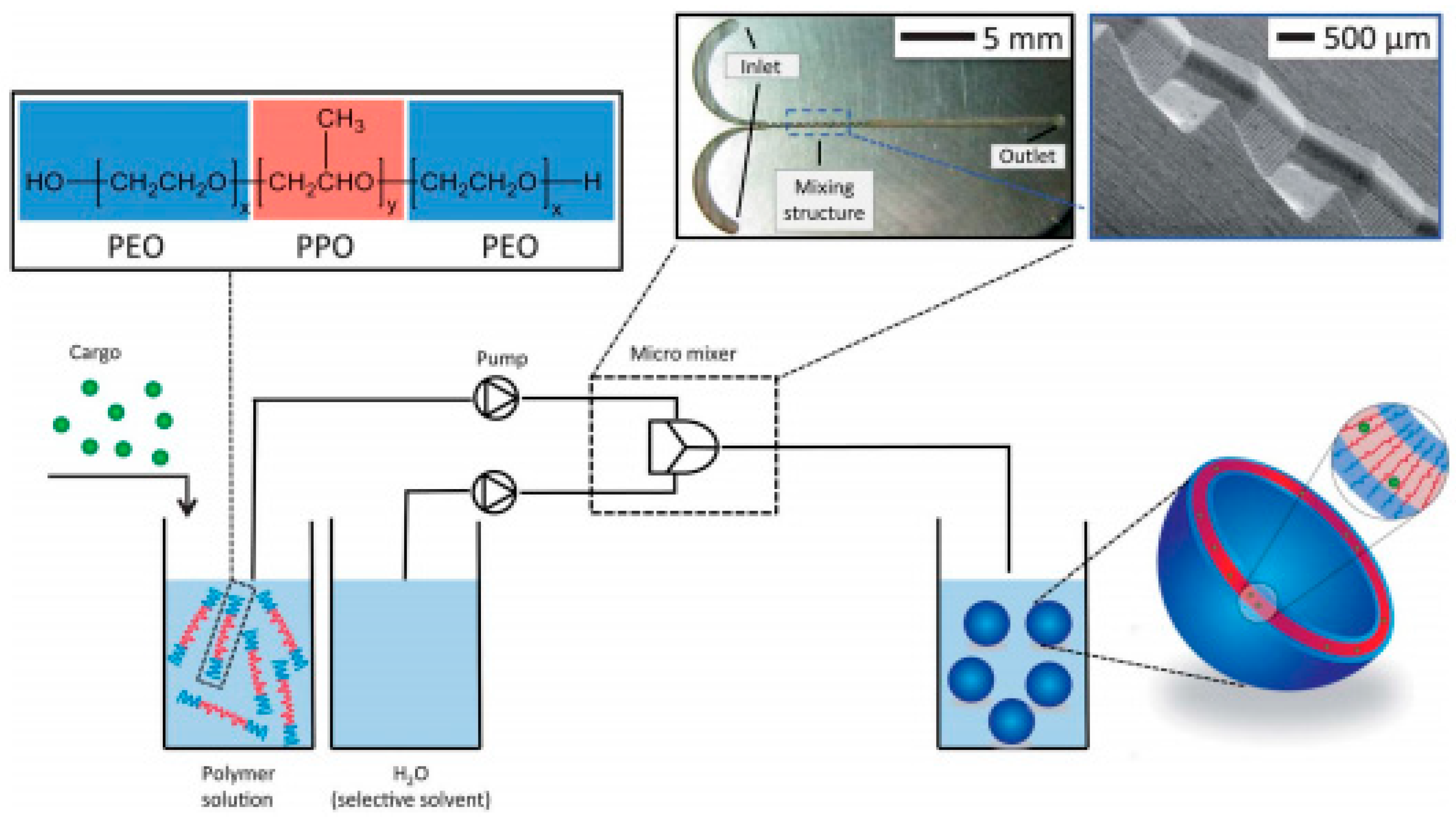

| MCIO/Polymer vesicle (Pluronic) | IONP/OA dispersed in tetrahydro furane (ferrofluid) | IONP embedded in polymer vesicle by microfluidic mixing | ≈160 a | - | [166] |

| MCIO/liposomes | ã-Fe3O4/citrate in water (ferrofluid) | encapsulation of IONP into the liposomes | 200 a | 3 × 105 A/m | [64] |

| MCIO/liposomes-PEG | Fe3O4 in water (suspension) | encapsulation of IONP into liposomes coated with PEG | 90–110 (AFM) | - | [155] |

| MCIO/liposomes-PEG/PEG-Folic acid/Doxorubicin | Fe3O4 in water (commercial ferrofluid) | encapsulation of IONP and doxorubicin into the liposomes coated with PEG and PEG + folic acid | 156 + −11 b 361 + −20 b | - | [220] |

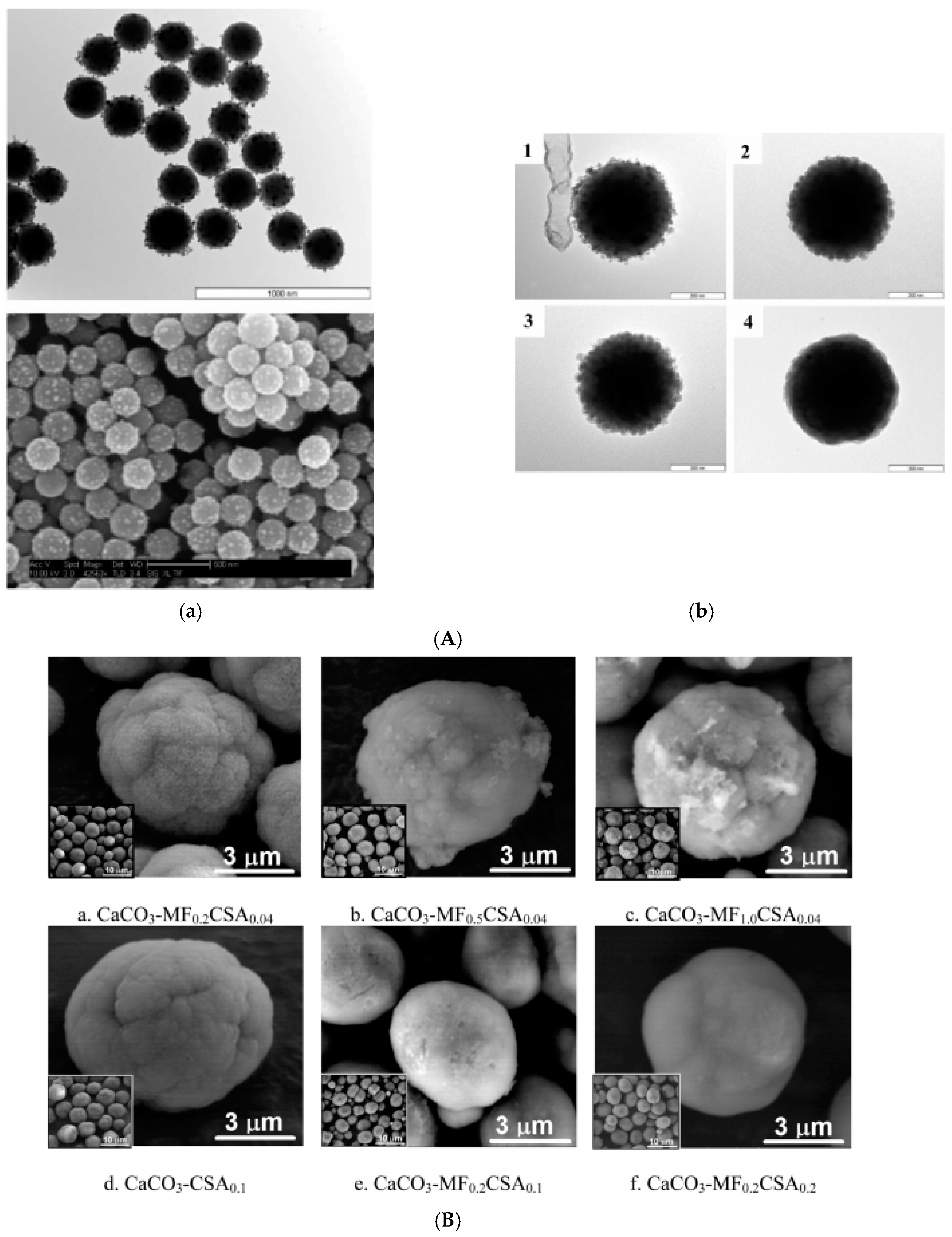

| MCIO/CaCO3 embedded | Fe3O4/(OA + OA) dispersed in water; aqueous ferrofluid | fast precipitation | 5–6 µm a | 0.44–2.88 | [167] |

| MCIO/Polymer-embedded colloidal assemblies | MnFe2O4/LA; Fe3O4/OA dispersed in toluene/tetrahydro furane | thermal decomposition/colloid destabilization by acetonitrile | 70–134 a | - | [65] |

| MCIO/CA obtained by fractionation | - | high temperature hydrolysis polyol approach | 19.7–28.8 a | 65.4–81.8 | [75] |

| MCIO | - | microwave irradiation | 100 a | 38.3 | [221] |

| Non-spherical particles/composites | |||||

| Assembled supraparticles: mgPS, mgPVP and binary TiO2/mgPS | Primary: OA-stabilized Fe3O4 and CoFe2O4 ferrofluids Secondary: mgPS: SDS-stabilized mg/PS NPs and mgPVPs (aqueous magnetic colloids) | evaporation-induced assembly | supraparticle assemblies: mm range | 52 | [172] |

| Anisometric, ellipsoidal magnetic Janus supraparticles | Aqueous suspensions of Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell NPs (20–30 nm) | evaporation-induced self-assembly | supraparticle assemblies: mm range | - | [171] |

| Magnetic halloysite nanotubes (HNT) | OA-coated Fe3O4 NPs (10 nm) in hexane (ferrofluid) | evaporation-induced self-assembly in the lumen of HNT (inner diameter 15 nm) | several hundreds of nm length magnetic HNTs | - | [175] |

| SMPs with dimpled and crumpled morphologies | Oleic acid-coated Fe3O4 NPs dispersed in hexane (ferrofluid) | emulsion-templated self-assembly | ìm range (average: 0.5 ìm) | - | [125] |

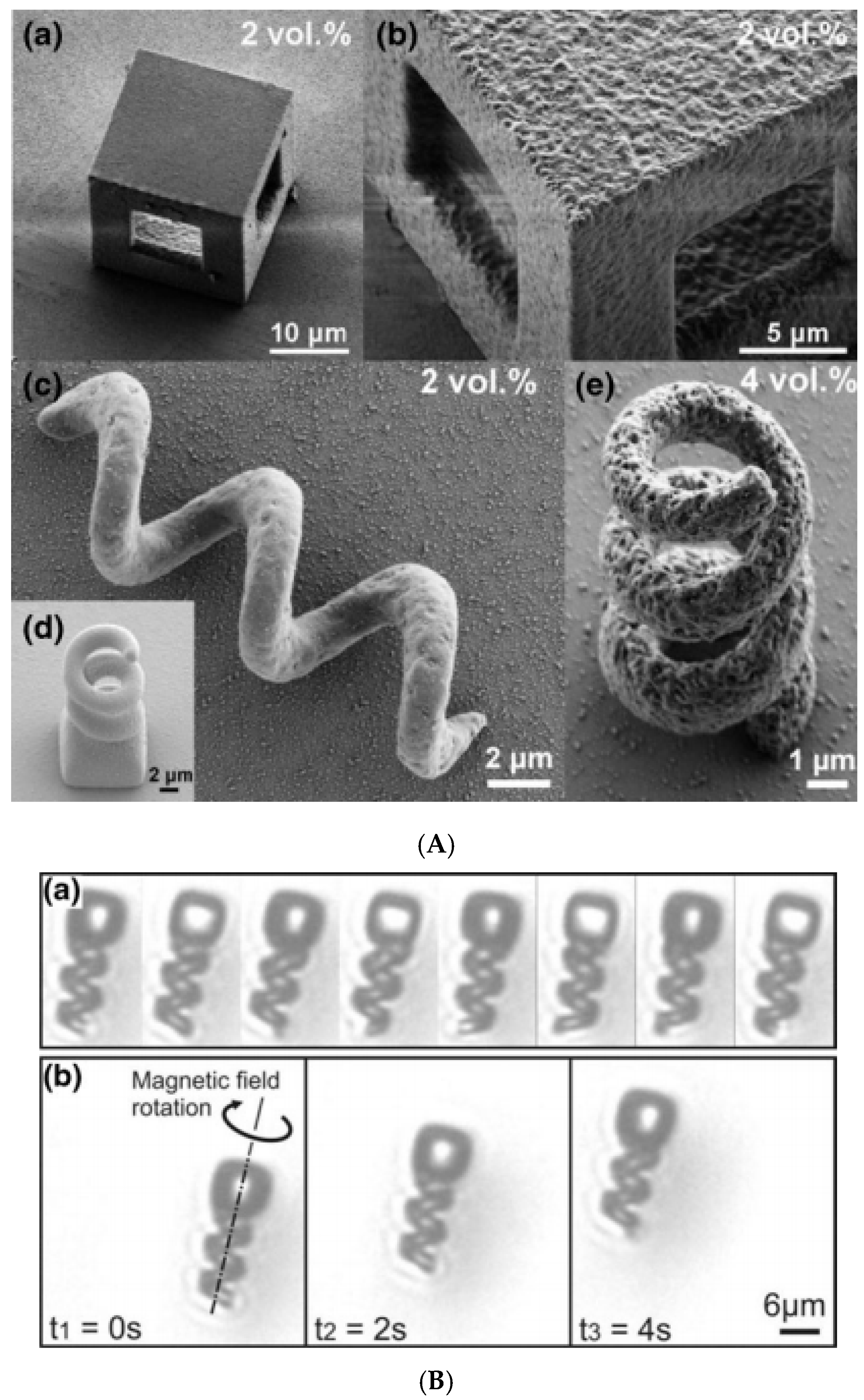

| 2D and 3D mesocrystalline films | Oleic acid-coated Fe3O4 truncated nanocubes in toluene (ferrofluid) (≈10 nm–AUC, HRTEM, SEM) | self-assembly | - | - | [176] |

| Nanochains/nanobundles | ã-Fe2O3 NP clusters encapsulated within silica shells (114, 146 nm-TEM) (aqueous ferrofluid) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | nanochains of various lengths consisting of different no. of nanoclusters (6–40) Nanobundles: ≈1–2 μm wide and ≈5–10 μm long | 15–45 | [177] |

| Nanofibers | Primary: OA-capped Fe3O4 nanoparticles (8 nm-TEM) Secondary: SDS-stabilized PS-capped Fe3O4 NPs (127–237 nm-DLS) (aqueous dispersions) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | PS-Mag-H Nanofibers: 6.4 ± 2.5 μm (average no of NPs/fiber: 55) PS-Mag-J nanofibers: 3.0 ± 1.1 (average no of NPs/fiber:13) | 84 | [178] |

| Polymer-like chains and networks | SDS-stabilized Fe3O4-loaded PS nanospheres (80–350 nm-DLS) (aqueous dispersions) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | statistical, block copolymer, branched and network-like morphologies (micrometer length-scale) | - | [179] |

| Self-assembled elongated Janus NP clusters | Janus magnetic nanoparticles (≈20 nm) prepared by grafting (PSSNa) or (PDMAEMA) to the surfaces of negatively charged PAA-coated Fe3O4 NPs | pH-triggered self-assembly | elongated NP clusters with tunable NP number | - | [183] |

| Helical magnetoresponsive superstructures | Hydrophobic silica particles dispersed in octane based ferrofluid | emulsion evaporation-induced magnetic field assisted self-assembly | asymmetric dumbbell-type configurations (micrometer length scale) | - | [208] |

| Agar-encapsulated anisotropic microrod supraparticles | SPIO NPs (10 nm) (aqueous ferrofluid) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | iron oxide and silica-coated iron oxide microrod supraparticles (20 to 100 nm in diameter and 100 nm to 10 μm in length) | 25–60 | [184] |

| Anisotropic rodlike supraparticle structures | SPIO NPs (10 nm) (ferrofluid) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | anisotropic rodlike supraparticles diameters: 30 to 300 nm; length: 100 nm to 10 μm | - | [185] |

| 3D self-assembled Fe3O4 NP layers on Si | Spherical, Fe3O4 NPs coated with OA (aqueous ferrofluid) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | - | [186] | |

| Ellipsoidal superparamagnetic nanoclusters | Oleate-capped iron oxide nanoparticles (ferrofluid in octane) | emulsion electrospinning | ellipsoidal superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoclusters average cluster diameter: equatorial axis: 94 nm; polar axis: 250 nm - STEM) | ~47 | [180] |

| 1D periodic magnetic NP arrays within electrospun polymer fibers | OA-coated iron oxide nanoparticles (18 nm) (ferrofluid) | magnetic field-assisted electrospinning | length of magnetic NP arrays: >1.5 μm | 0.77 | [204] |

| Helical nanocrystal superstructures | Fe3O4 cubic, rounded cubic, octahedral Fe3O4 nanocrystals, and Fe3O4-Ag heterodimeric particles (10–15 nm) (ferrofluids) | magnetic field-assisted self-assembly | large domains (up to 1 mm2) consisting of enantiopure helices | - | [209] |

| MHMS rods | Stearic acid-stabilized Fe3O4 nanocrystals (6 nm-TEM) dispersed in CHCl3 (ferrofluid) | self-assembly | MHMS length: ∼150–200 nm; diameter: from ∼50 to 60 nm. | 2.49 | [222] |

| 1D arrays of SPIO NPs | Fe3O4 NPs, shell-functionalized with a dopamine sulfonate zwitterionic ligand and catechol-modified hydrophobic dye | Mg2+-mediated supramolecular polymerization | length: micrometer range | - | [223] |

| 1D assemblies of Fe3O4 nanocrystals | Poly(4-styrenesulfonic acid-co-maleic acid) sodium salt-protected Fe3O4 nanocrystals (ferrofluid); ≈320 nm | ink-jet printing | 1D NP assemblies length ≈31.0 µm | 52 | [214] |

| PAM hydrogel-encapsulated linear NP assemblies | 15 nm single Fe3O4 NPs and 200 nm core–shell Fe3O4@carboxylated SiO2 nanospheres | magnetic field-directed assembly | linear NP assemblies with L/D ratio up to 102–103 | ~25 | [94] |

| Stripe-like NP patterns | Primary γ-Fe2O3 NPs forming ≈230 nm clusters | magnetic field-directed assembly | micro-scaled size assemblies (20 μm wide and ~400 nm high) | - | [215] |

| Micro-sized NP assemblies of different geometries (cylinders, stars, triangles, cubes, etc.) forming chains on application of magnetic field | 300 nm diameter silica-coated SPIO colloids | micro-lithography/magnetic field-assisted assembly | sub-5 micron superparamagnetic NP assemblies with variable shapes; micrometer-long magnetic field-mediated chain assemblies | - | [216] |

4. Structuring Processes Small-Angle Scattering Investigations

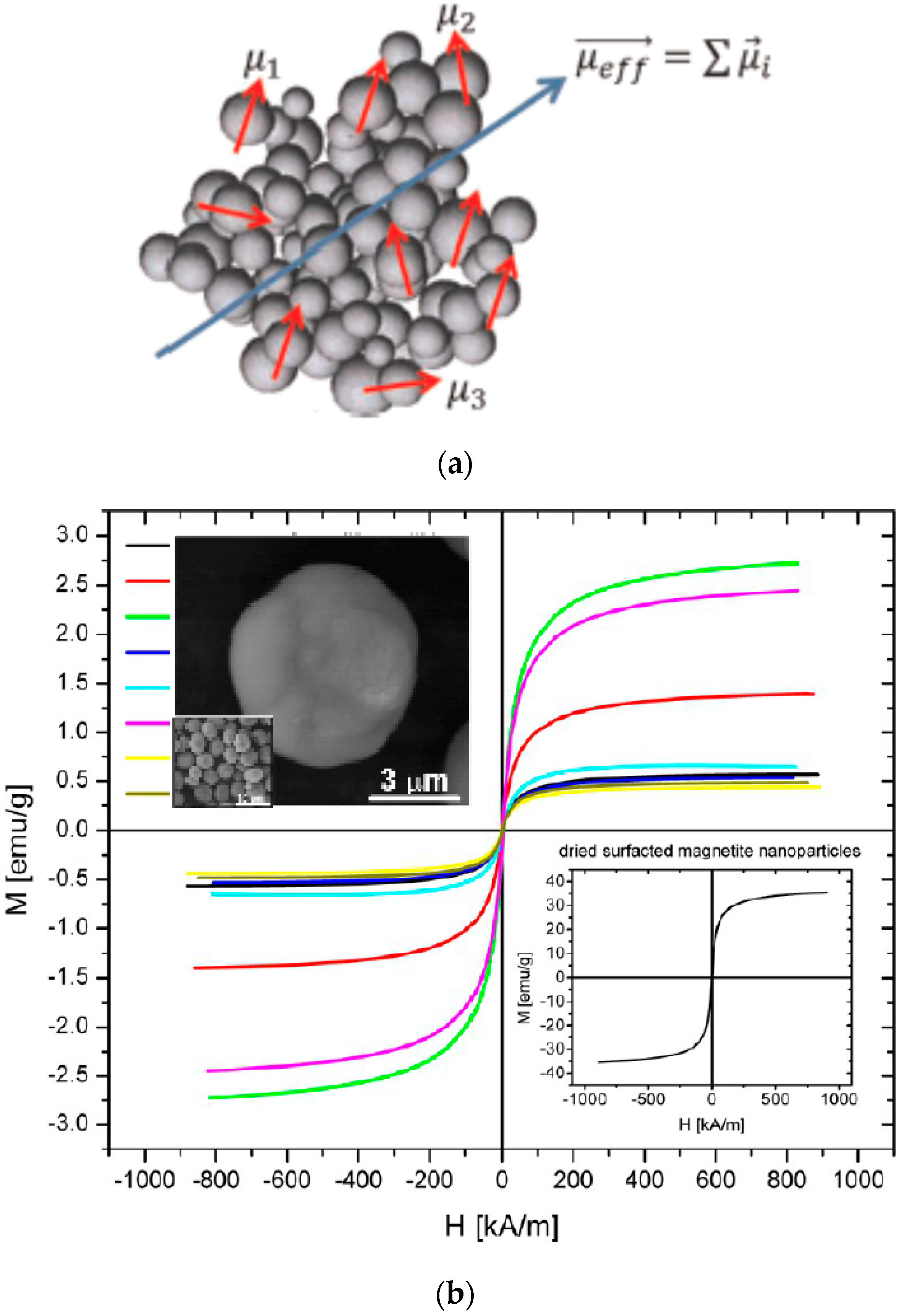

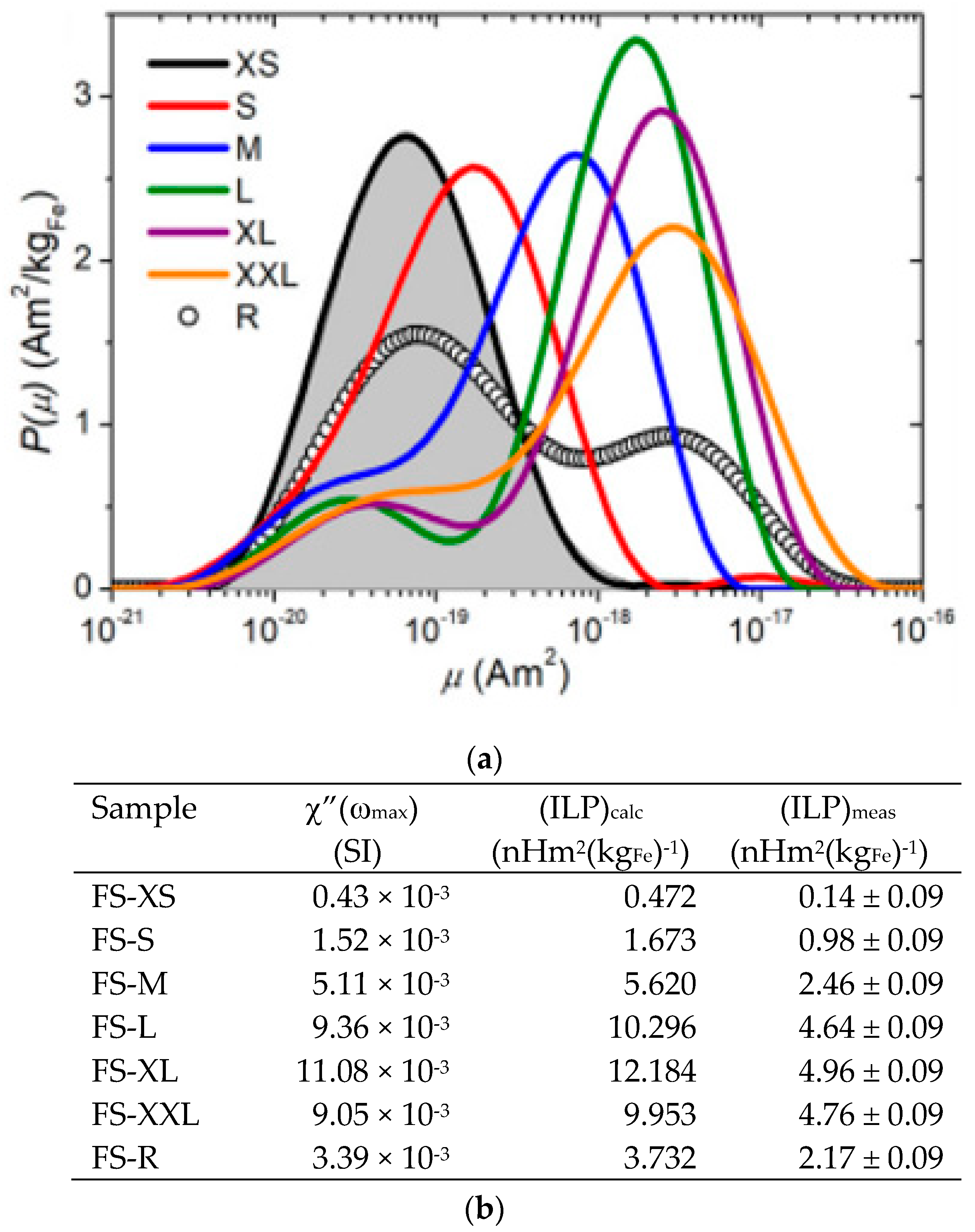

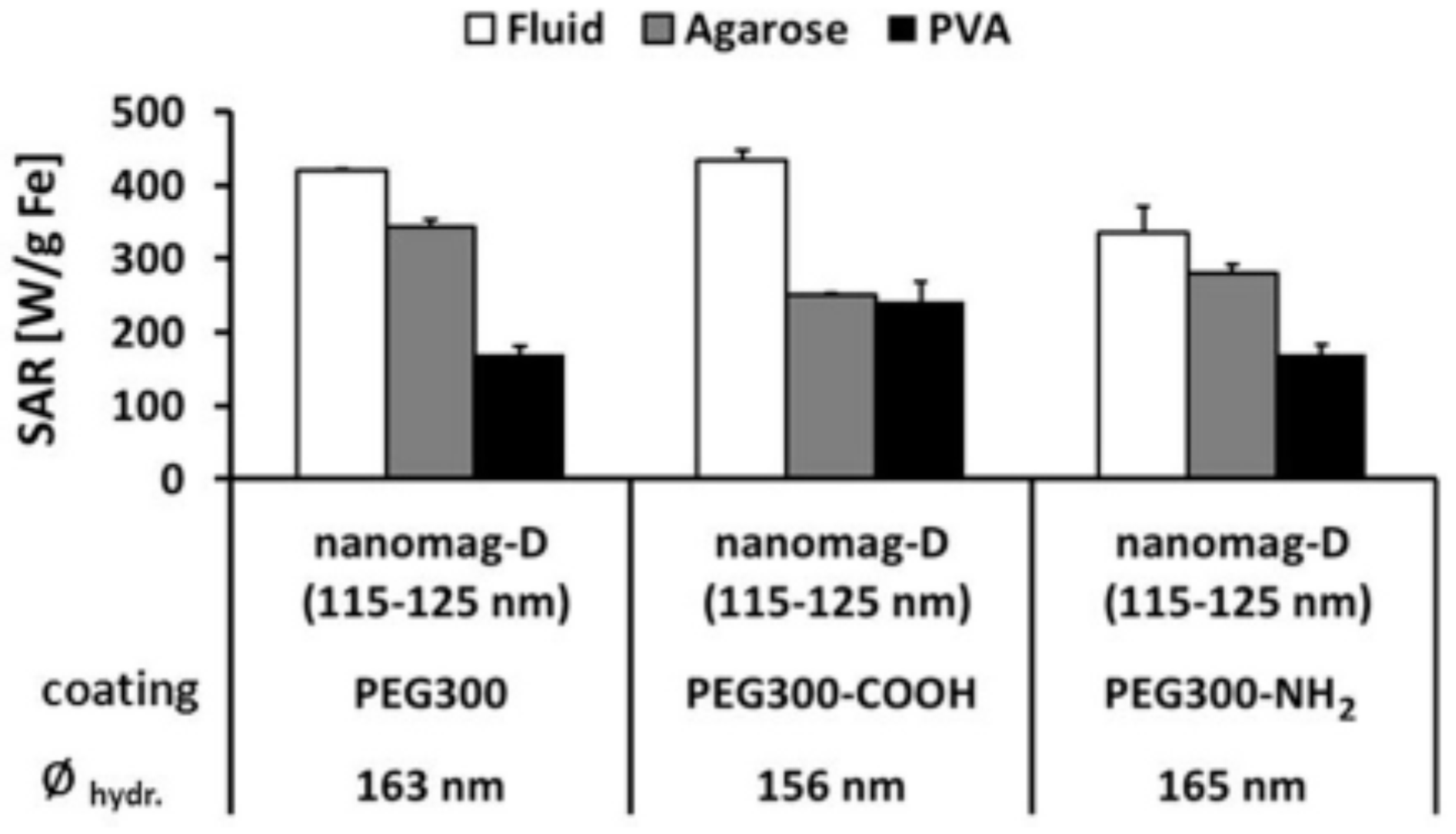

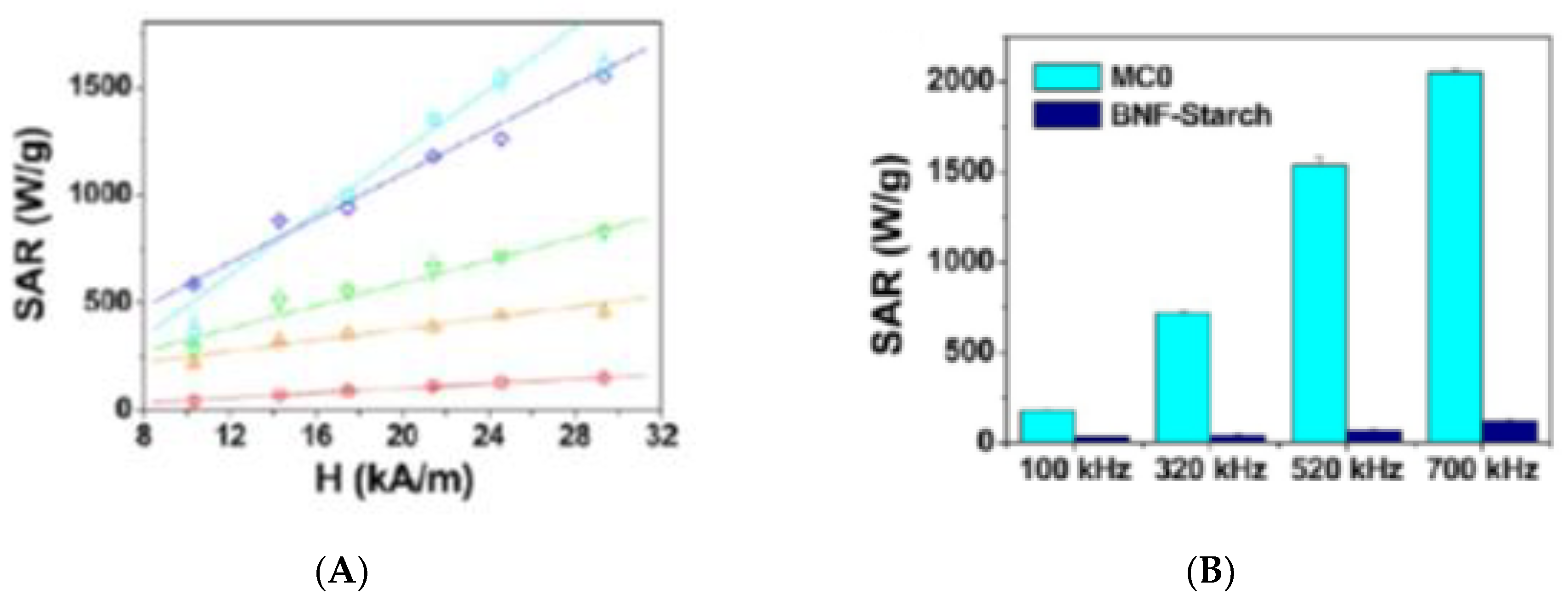

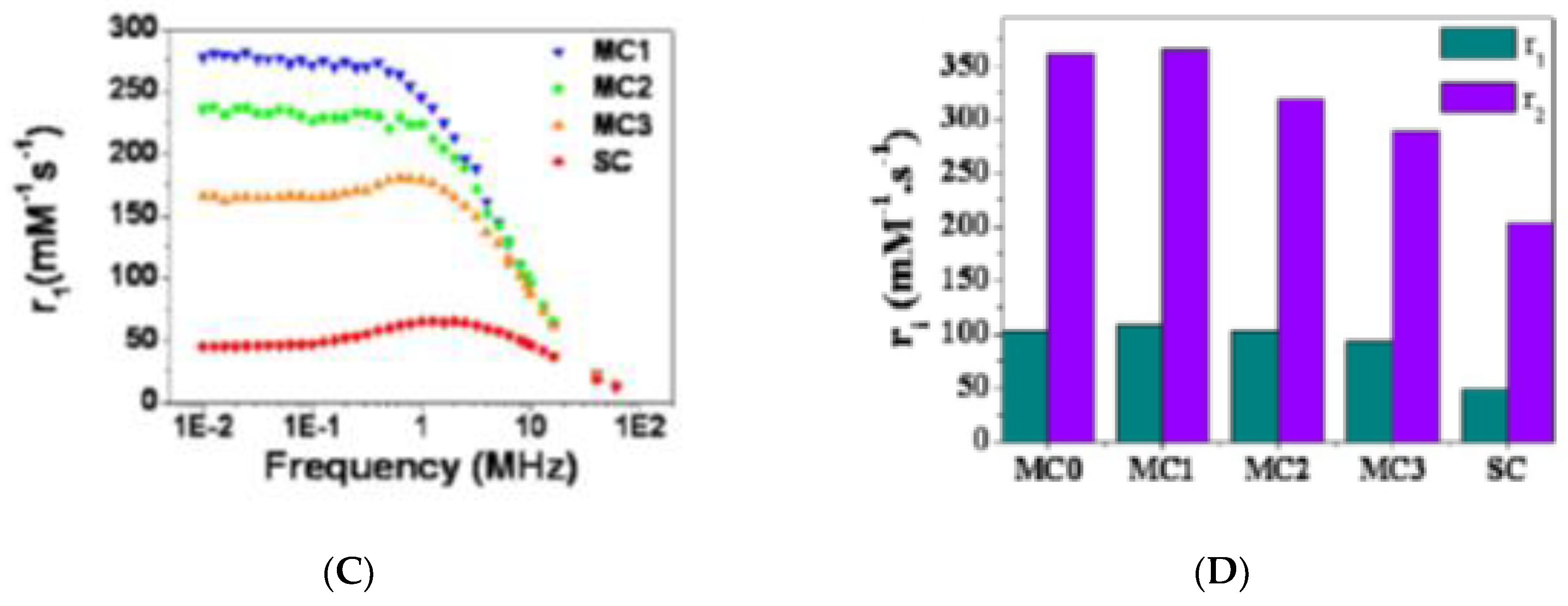

5. Magnetic Behavior

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Häfeli, U.O. Magnetic nano- and microparticles for targeted drug delivery. In Smart Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine—The Mml Series; Arshady, R., Kono, K., Eds.; Kentus Books: London, UK, 2006; pp. 77–126. [Google Scholar]

- Andrä, W.; Häfeli, U.; Hergt, R.; Misri, R. Application of magnetic particles in medicine and biology. In Handbook of Magnetism and Advanced Magnetic Materials; Kronmuller, H., Parkin, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov, G.B.; Rogach, A.L.; Springer, M.G.S.; Parak, W.J.; Muñoz-Javier, A.; Kreft, O.; Skirtach, A.G.; Susha, A.S.; Ramaye, Y.; Palankar, R.; et al. Multifunctionalized Polymer Microcapsules: Novel Tools for Biological and Pharmacological Applications. Small 2007, 3, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figuerola, A.; Di Corato, R.; Manna, L.; Pellegrino, T. From iron oxide nanoparticles towards advanced iron-based inorganic materials designed for biomedical applications. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 126–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigall, N.C.; Parak, W.J.; Dorfs, D. Fluorescent, magnetic and plasmonic—Hybrid multifunctional colloidal nano objects. Nano Today 2012, 7, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, M.V.; Manna, L.; Cabot, A.; Hens, Z.; Talapin, D.V.; Kagan, C.R.; Klimov, V.I.; Rogach, A.L.; Reiss, P.; Milliron, D.J.; et al. Prospects of Nanoscience with Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 1012–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, N.T.K. (Ed.) Clinical Applications of Magnetic Nanoparticles Design to Diagnosis Manufacturing to Medicine; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeel, B.; Alexiou, C. Brave new world revisited: Focus on nanomedicine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Willner, I. Integrated Nanoparticle–Biomolecule Hybrid Systems: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6042–6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanson, C.; Diou, O.; Thevenot, J.; Ibarboure, E.; Soum, A.; Brulet, A.; Miraux, S.; Thiaudiere, E.; Tan, S.; Brisson, A.; et al. Doxorubicin Loaded Magnetic Polymersomes: Theranostic Nanocarriers for MR Imaging and Magneto-Chemotherapy. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1122–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, A.G.; Gutiérrez, L.; Gavilán, H.; Brollo, M.E.F.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; Morales, M.P. Design strategies for shape-controlled magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 138, 68–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Synthesis, Properties and Applications of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Nanowires—A Brief Introduction. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankhurst, Q.A.; Connolly, J.; Jones, S.K.; Dobson, J. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2003, 36, R167–R181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gu, H.; Xu, B. Multifunctional Magnetic Nanoparticles: Design, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiseh, O.; Gunn, J.W.; Zhang, M. Design and fabrication of magnetic nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and imaging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, S.; Dutz, S.; Hafeli, U.O.; Mahmoudi, M. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia: Focus on superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 166, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Carregal-Romero, S.; Casula, M.F.; Gutierrez, L.; Morales, M.P.; Bohm, I.G.; Heverhagen, J.T.; Prosperi, D.; Parak, W.J. Biological applications of magnetic nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4306–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutz, S.; Hergt, R. Magnetic nanoparticle heating and heat transfer on a microscale: Basic principles, realities and physical limitations of hyperthermia for tumour therapy. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, E.; Wang, F.; Xue, J.M. Nanostructured magnetic nanocomposites as MRI contrast agents. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 2241–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, N.; Duschka, R.L.; Ahlborg, M.; Bringout, G.; Debbeler, C.; Graeser, M.; Kaethner, C.; Lüdtke-Buzug, K.; Medimagh, H.; Stelzner, J.; et al. Magnetic particle imaging: Current developments and future directions. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 3097–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perigo, E.A.; Hemery, G.; Sandre, O.; Ortega, D.; Garaio, E.; Plazaola, F. Fundamentals and advances in magnetic hyperthermia. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 041302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, R.; Zaloga, J.; Unterweger, H.; Lyer, S.; Friedrich, R.P.; Janko, C.; Pottler, M.; Dürr, S.; Alexiou, C. Magnetic nanoparticle-based drug delivery for cancer therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Roy, I.; Yang, C.; Prasad, P.N. Nanochemistry and Nanomedicine for Nanoparticle-based Diagnostics and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2826–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaz, B.; Alexiou, C.; Alvarez-Puebla, R.A.; Alves, F.; Andrews, A.M.; Ashraf, S.; Balogh, L.P.; Ballerini, L.; Bestetti, A.; Brendel, C.; et al. Diverse applications of nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2313–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, T.L.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L.; Hirsch, V.; Balog, S.; Urban, D.; Jud, C.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Lattuada, M.; Petri-Fink, A. Nanoparticle colloidal stability in cell culture media and impact on cellular interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6287–6305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlard, A.-C.; Wald, S.; Crespy, D.; Taden, A.; Wurm, F.R.; Landfester, K. Functional Colloidal Stabilization. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 16004430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, D.; Sandre, O.; Bégin-Colin, S. Drug releasing nanoplatforms activated by alternating magnetic fields. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1861, 1617–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimhult, E.; Schroffenegger, M.; Lassenberger, A. Design Principles for Thermoresponsive Core−Shell Nanoparticles: Controlling Thermal Transitions by Brush Morphology. Langmuir 2019, 35, 7092–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangijzegem, T.; Stanicki, D.; Laurent, S. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for drug delivery: Applications and characteristics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, E.; Textor, M.; Reimhult, E. Stabilization and functionalization of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 2819–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirbs, R.; Lassenberger, A.; Vonderhaid, I.; Kurzhals, S.; Reimhult, E. Melt-grafting for the synthesis of core–shell nanoparticles with ultra-high dispersant density. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11216–11225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixner, O.; Lassenberger, A.; Baurecht, D.; Reimhult, E. Complete Exchange of the Hydrophobic Dispersant Shell on Monodisperse Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2015, 31, 9198–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klokkenburg, M.; Dullens, R.P.A.; Kegel, W.K.; Erne, B.H.; Philipse, A.P. Quantitative Real-Space Analysis of Self-Assembled Structures of Magnetic Dipolar Colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 037203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.J.M.; Wilmer, C.E.; Soh, S.; Grzybowski, B.A. Nanoscale forces and their uses in self-assembly. Small 2009, 5, 1600–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

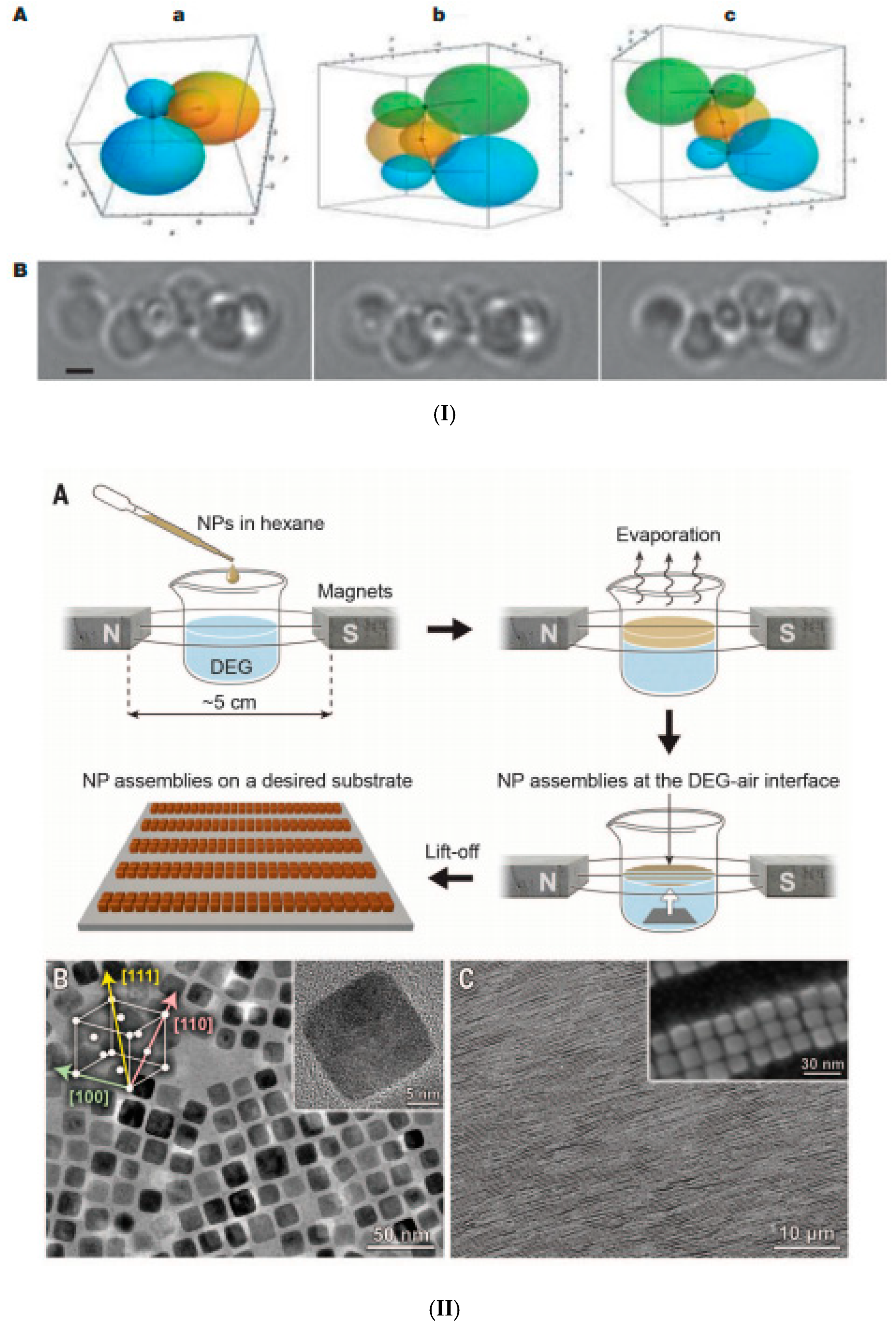

- Erb, R.M.; Son, H.S.; Samanta, B.; Rotello, V.M.; Yellen, B.B. Magnetic assembly of colloidal superstructures with multipole symmetry. Nature 2009, 457, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, K.M. Biomedical Nanomagnetics: A Spin through Possibilities in Imaging, Diagnostics, and Therapy (review). IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 2523–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Nelson, A. Magnetically-Responsive Self Assembled Composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4057–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, R.J.; Haynes, A.S.; Kikkawa, J.M.; Park, S.-J. Controlling the Self-Assembly Structure of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Amphiphilic Block-Copolymers: From Micelles to Vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Josephson, D.P.; Stein, A. Colloidal Assembly: The Road from Particles to Colloidal Molecules and Crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 360–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, M.; Lattuada, M. Use of Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Preparation of Micro- and Nanostructured Materials. In Advanced Hierarchical Nanostructured Materials, 1st ed.; Zhang, Q., Wei, F., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KgaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; pp. 71–118. [Google Scholar]

- Manoharan, V.N. Colloidal Matter: Packing, Geometry, and Entropy. Science 2015, 349, 1253751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersonsky, R.K.; van Anders, G.; Dodd, P.M.; Glotzer, S.C. Relevance of packing to colloidal self-assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Huang, X.; Li, F.; Davis, T.P.; Qiao, R.; Ling, D. Polymer-Assisted Magnetic Nanoparticle Assemblies for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Biol. Mater. 2020, 3, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Hu, Y.; Biasini, M.; Beyermann, W.P.; Yin, Y. Superparamagnetic Magnetite Colloidal Nanocrystal Clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4342–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Yin, Y. Colloidal nanoparticle clusters: Functional materials by design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6874–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K.; Park, J.M. Iron oxide-based superparamagnetic polymeric nanomaterials: Design, preparation, and biomedical application. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenot, J.; Oliveira, H.; Sandre, O.; Lecommandoux, S. Magnetic responsive polymer composite materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7099–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhu, J. Surface Engineering of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles by Polymer Grafting: Synthesis Progress and Biomedical Applications. Nanoscale 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Margel, S. Review: Remotely controlled magneto-regulation of therapeutics from magnetoelastic gel matrices. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 44, 107611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyei, A.; Widder, K.; Czerlinski, C. Magnetic guidance of drug carrying microspheres. J. Appl. Phys. 1978, 49, 3578–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raikher, Y.L.; Stepanov, V.I. Nonlinear dynamic susceptibilities and field-induced birefringence in magnetic particle assemblies. In Advances in Chemical Physics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 129. [Google Scholar]

- Claesson, E.M.; Philipse, A.P. Monodisperse Magnetizable Composite Silica Spheres with Tunable Dipolar Interactions. Langmuir 2005, 21, 9412–9419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, T.-J.; Lee, H.; Shao, H.; Hilderbrand, S.A.; Weissleder, R. Multicore assemblies potentiate magnetic properties of biomagnetic nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4793–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.K.; Yuet, K.; Hwang, D.K.; Bong, K.W.; Doyle, P.S.; Hatton, T.A. Synthesis of nonspherical superparamagnetic particles: In situ coprecipitation of magnetic nanoparticles in microgels prepared by stop-flow lithography. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7337–7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulou, A.; Lappas, A. Colloidal magnetic nanocrystal clusters: Variable length-scale interaction mechanisms, synergetic functionalities and technological advantages. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2015, 4, 595–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkov, A.V.; Melenev, P.V.; Balasoiu, M.; Raikher, Y. Structure organization and magnetic properties of microscale ferrogels: The effect of particle magnetic anisotropy. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 074905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molday, R.S.; Yen, S.P.S.; Rembaum, A. Application of magnetic microspheres in labelling and separation of cells. Nature 1977, 268, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbach, K.; Andersson, L. Magnetic ferrofluids for preparation of magnetic polymers and their application in affinity chromatography. Nature 1977, 270, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widder, K.J.; Senyei, A.E.; Scarpelli, D.G. Magnetic Microspheres: A Model System for Site Specific Drug Delivery in Vivo. Exp. Biol. Med. 1978, 158, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenyi, S.; Muller, W.; Weichel, W.; Radbruch, A. High Gradient Magnetic Cell Separation with MACS. Cytometry 1990, 11, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelstad, J.; Stenstad, P.; Kilaas, L.; Prestvik, W.S.; Herje, R.; Berge, A.; Hornes, E. Monodisperse Magnetic Polymer Particles. Blood Purif. 1993, 11, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfester, K.; Musyanovych, A.; Mailander, V. From Polymeric Particles to Multifunctional Nanocapsules for Biomedical Applications Using the Miniemulsion Process. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Kettering, M.; Hilger, I.; Müller, R.; Zeisberger, M. Magnetic multicore nanoparticles for hyperthermia–influence of particle immobilization in tumour tissue on magnetic properties. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 265102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béalle, G.; Di Corato, R.; Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J.; Dupuis, V.; Clément, O.; Gazeau, F.; Wilhelm, C.; Menager, C. Ultra magnetic liposomes for MR imaging, targeting, and hyperthermia. Langmuir 2012, 28, 11834–11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigall, N.C.; Wilhelm, C.; Beoutis, M.-L.; García-Hernandez, M.; Khan, A.A.; Giannini, C.; Sánchez-Ferrer, A.; Mezzenga, R.; Materia, M.E.; Garcia, M.A.; et al. Colloidal ordered assemblies in a polymer shell—A novel type of magnetic nanobeads for theranostic applications. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberbeck, D.; Dennis, C.L.; Huls, N.F.; Krycka, K.L.; Gruttner, C.; Westphal, F. Multicore Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Particle Imaging. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.C.N.; Lo, I.M.C. Magnetic nanoparticles: Essential factors for sustainable environmental applications. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2613–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Andujar, C.; Ortega, D.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A.; Thanh, N.T.K. High performance multi-core iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia: Microwave synthesis, and the role of core-to-core interactions. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1768–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, S.; Appel, I. Magnetic nanocomposites. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 39, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudr, J.; Haddad, Y.; Richtera, L.; Heger, Z.; Cernak, M.; Adam, V.; Zitka, O. Magnetic Nanoparticles: From Design and Synthesis to Real World Applications. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratz, H.; Taupitz, M.; de Schellenberger, A.; Kosch, O.; Eberbeck, D.; Wagner, S.; Trahms, L.; Hamm, B.; Schnorr, J. Novel magnetic multicore nanoparticles designed for MPI and other biomedical applications: From synthesis to first in vivo studies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antone, A.J.; Sun, Z.; Bao, Y. Preparation and Application of Iron Oxide Nanoclusters. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, H.; Mohtashamdolatshahi, A.; Eberbeck, D.; Kosch, O.; Hauptmann, R.; Wiekhorst, F.; Taupitz, M.; Hamm, B.; Schnorr, J. MPI Phantom Study with A High-Performing Multicore Tracer Made by Coprecipitation. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartigue, L.; Coupeau, M.; Lesault, M. Luminophore and Magnetic Multicore Nanoassemblies for Dual-Mode MRI and Fluorescence Imaging. Nanomaterials 2019, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lartigue, L.; Hugounenq, P.; Alloyeau, D.; Clarke, S.P.; Lévy, M.; Bacri, J.-C.; Bazzi, R.; Brougham, D.F.; Wilhelm, C.; Gazeau, F. Cooperative Organization in Iron Oxide Multi-Core Nanoparticles Potentiates Their Efficiency as Heating Mediators and MRI Contrast Agents. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 10935–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; Costo, R.; Grüttner, C.; Westphal, F.; Gehrke, N.; Heinke, D.; Fornara, A.; Pankhurst, Q.A.; Johansson, C.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; et al. Synthesis Methods to Prepare Single- and Multi-core Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 2943–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

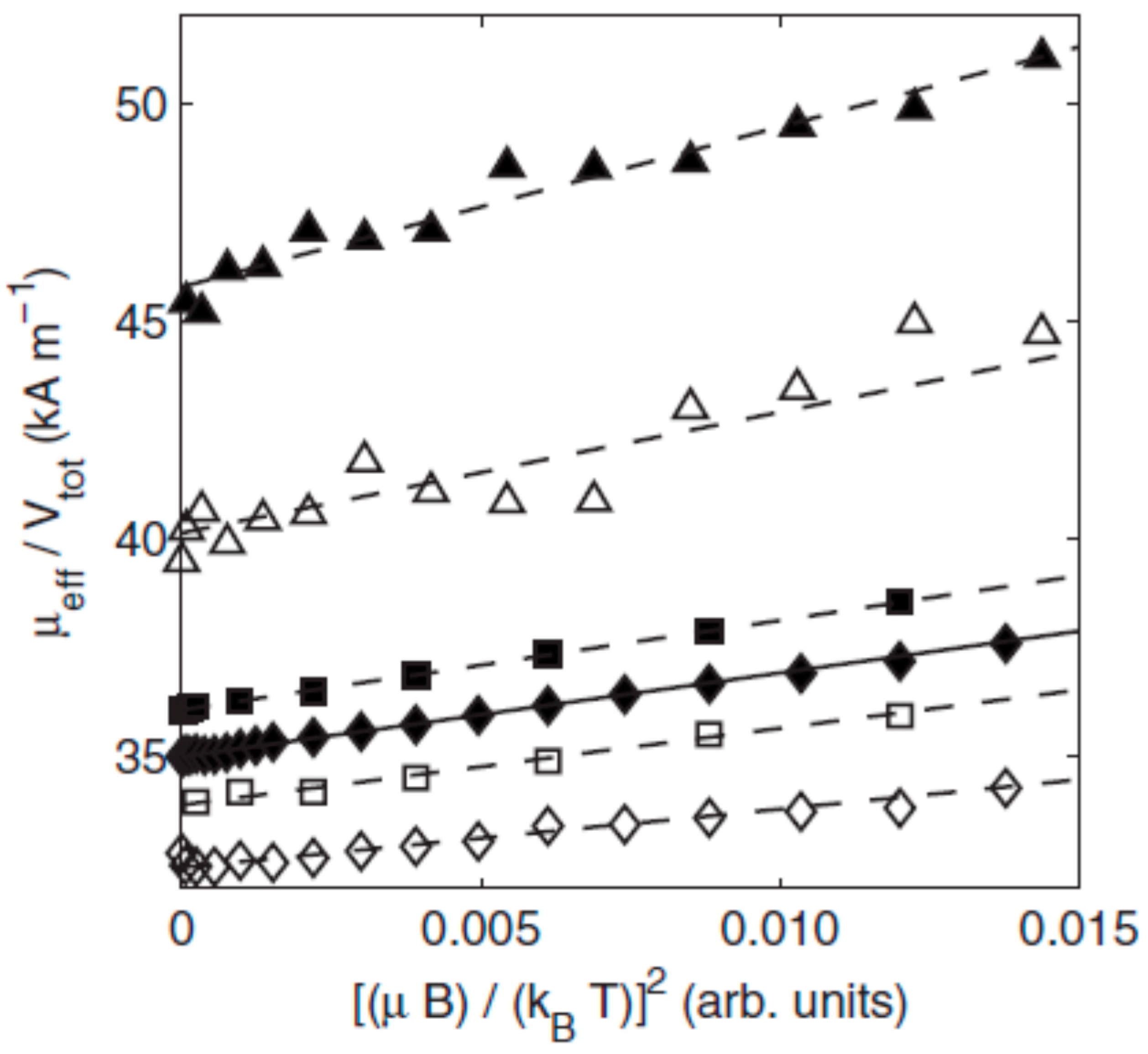

- Ahrentorp, F.; Astalan, A.; Blomgren, J.; Jonasson, C.; Wetterskog, E.; Svedlindh, P.; Lak, A.; Ludwig, F.; van IJzendoorn, L.J.; Westphal, F.; et al. Effective particle magnetic moment of multi-core particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2015, 380, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S. Are Magnetic Multicore Nanoparticles Promising Candidates for Biomedical Applications? IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 0200103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahmann, T.; Ludwig, F. Magnetic field dependence of the effective magnetic moment of multi-core nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 233901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

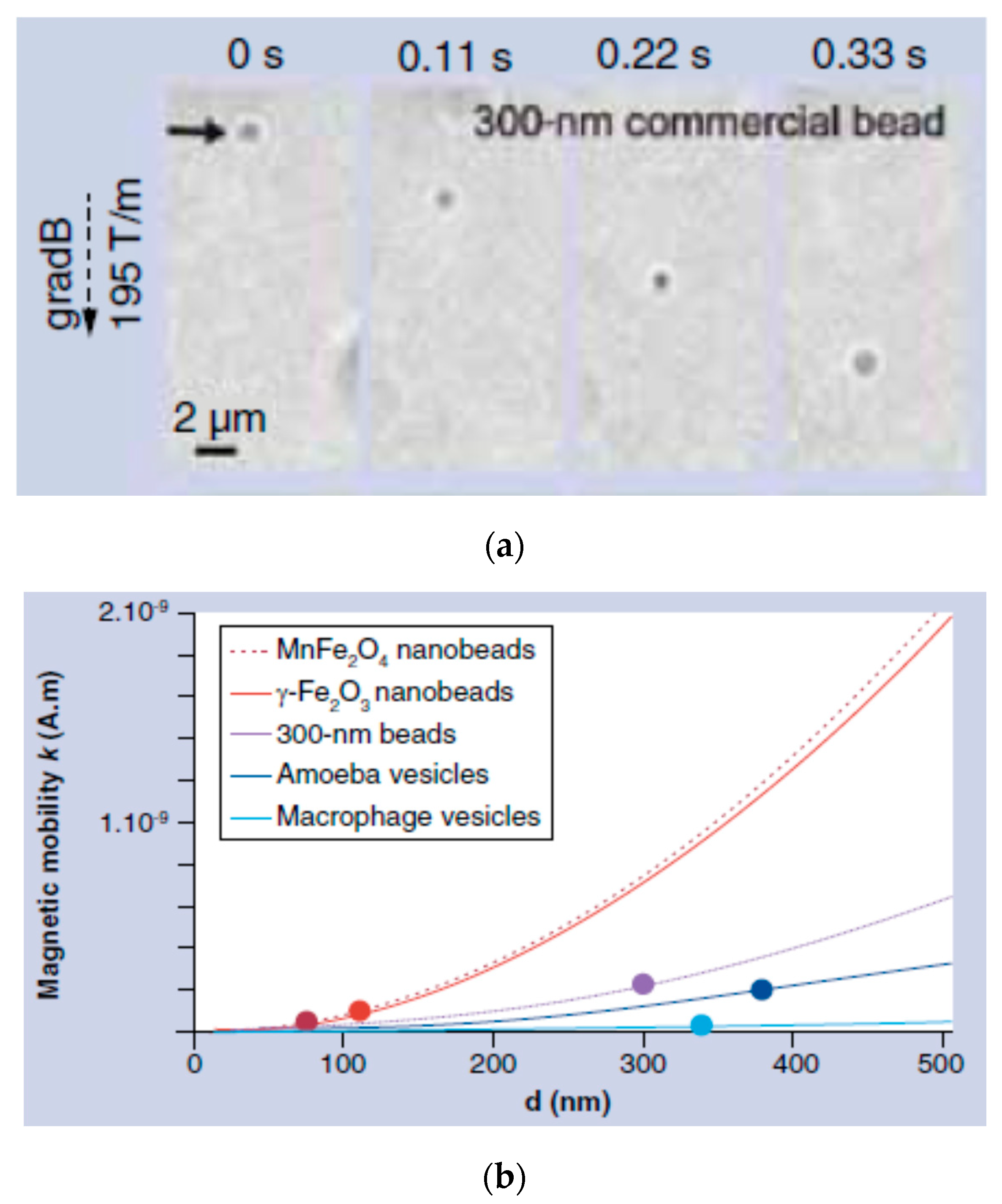

- Silva, A.K.A.; Di Corato, R.; Gazeau, F.; Pellegrino, T.; Wilhelm, C. Magnetophoresis at the nanoscale: Tracking the magnetic targeting efficiency of nanovectors. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, S.; Saei, A.A.; Behzadi, S.; Panahifar, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for delivery of therapeutic agents: Opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1449–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombácz, E.; Turcu, R.; Socoliuc, V.; Vékás, L. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Recent trends in design and synthesis of magnetoresponsive nanosystems. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illés, E.; Szekeres, M.; Tóth, I.Y.; Szabó, A.; Iván, B.; Turcu, R.; Vékás, L.; Zupkó, I.; Jaics, G.; Tombácz, E. Multifunctional PEG-carboxylate copolymer coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical application. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 451, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutz, S.; Clement, J.H.; Eberbeck, D.; Gelbrich, T.; Hergt, R.; Müller, R.; Wotschadlo, J.; Zeisberger, M. Ferrofluids of magnetic multicore nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, J.; Wolf, D.; Odenbach, S. A rheological and microscopical characterization of biocompatible ferrofluids. J. Magn.Magn.Mater. 2014, 354, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan-Resiga, D.; Socoliuc, V.; Bunge, A.; Turcu, R.; Vékás, L. From high colloidal stability ferrofluids to magnetorheological fluids: Tuning the flow behavior by magnetite nanoclusters. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Lühe, M.; Gunther, U.; Weidner, A.; Grafe, C.; Clement, J.H.; Dutz, S.; Schacher, F.H. SPION@polydehydroalanine hybrid particles. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 31920–31929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombácz, E.; Farkas, K.; Földesi, I.; Szekeres, M.; Illés, E.; Tóth, I.Y.; Nesztor, D.; Szabó, T. Polyelectrolyte coating on superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as interface between magnetic core and biorelevant media. Interface Focus 2016, 6, 20160068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder-Flesch, D.; Mertz, D.; Parat, A.; Begin-Colin, S. 4.3. Coatings for Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. In Contrast Agents for MRI. Experimental Methods; Pierre, C.V., Allen, M.J., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018; pp. 339–361. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, L.P.; Landfester, K. Magnetic polystyrene nanoparticles with a high magnetite content obtained by miniemulsion processes. Macromol.Chem. Phys. 2003, 204, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacanna, S.; Philipse, A.P. Preparation and Properties of Monodisperse Latex Spheres with Controlled Magnetic Moment for Field-Induced Colloidal Crystallization and (Dipolar) Chain Formation. Langmuir 2006, 22, 10209–10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Elaissari, A. Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Magnetic Latex. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2010, 233, 237–281. [Google Scholar]

- Lobaz, V.; Klupp Taylor, R.N.; Peukert, W. Highly magnetizable superparamagnetic colloidal aggregates with narrowed size distribution from ferrofluid emulsion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 374, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Sun, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Q.; Ma, M.; Gu, N. A novel magnetic hydrogel with aligned magnetic colloidal assemblies showing controllable enhancement of magnetothermal effect in the presence of alternating magnetic field. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2507–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Hu, Y.X.; Kim, H.; Ge, J.P.; Kwon, S.; Yin, Y.D. Magnetic assembly of nonmagnetic particles into photonic crystal structures. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4708–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.H.; Yellen, B.B. Magnetically tunable self-assembly of colloidal rings. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 083105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjeltorp, A.T. One- and two-dimensional crystallization of magnetic holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, Y.; Ge, J. The magnetic assembly of polymer colloids in a ferrofluid and its display applications. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, A.R.; Fischer, B.; Mao, L.; Hur Koser, H. Label-free cellular manipulation and sorting via biocompatible ferrofluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21478–21483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, L.; Lopez, G.P.; Yellen, B.B. Tunable Assembly of Colloidal Crystal Alloys Using Magnetic Nanoparticle Fluids. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2705–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantorovich, S.; Weeber, R.; Cerda, J.J.; Holm, C. Ferrofluids with shifted dipoles: Ground state structures. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacanna, S.; Rossi, L.; Pine, D.J. Magnetic Click Colloidal Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6112–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrikosov, A.I.; Sacanna, S.; Philipse, A.P.; Linse, P. Self-assembly of spherical colloidal particles with off-centered magnetic dipoles. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 8904–8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Qin, Y.; Lee, J.; Liao, H.; Wang, N.; Davis, T.P.; Qiao, R.; Ling, D. Stimuli-responsive nano-assemblies for remotely controlled drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2020, 322, 566–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vékás, L.; Avdeev, M.V.; Bica, D. Magnetic Nanofluids: Synthesis and Structure. In NanoScience in Biomedicine; Shi, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 645–704. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Diaz, I.; Rinaldi, C. Recent progress in ferrofluids research: Novel applications of magnetically controllable and tunable fluids. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 8584–8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A.; Mathew, S. Ferrofluids: Synthetic Strategies, Stabilization, Physicochemical Features, Characterization, and Applications. ChemPlusChem 2014, 79, 1382–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socoliuc, V.-M.; Vékás, L. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic magnetite nanoparticles: Synthesis by chemical coprecipitation and physico-chemical characterization. In Upscaling of Bio-Nano-Processes; Nirschl, H., Keller, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.; Kazakova, O.; Posth, O.; Steinhoff, U.; Petronis, S.; Bogart, L.K.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.; Johansson, C. Standardisation of magnetic nanoparticles in liquid suspension. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 383003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanicki, D.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N.; Laurent, S.; Felder-Flesch, D.; Mertz, D.; Parat, A.; Begin-Colin, S.; Cotin, G.; Greneche, J.-M.; et al. Iron-oxide Nanoparticle-based Contrast Agents. In Contrast Agents for MRI: Experimental Methods; Pierre, V.C., Allen, M.J., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018; pp. 318–344. [Google Scholar]

- Socoliuc, V.; Peddis, D.; Petrenko, V.I.; Avdeev, M.V.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Szabó, T.; Turcu, R.; Tombácz, E.; Vékás, L. Magnetic nanoparticle systems for nanomedicine–A materials science perspective. Magnetochemistry 2020, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibette, J. Monodisperse ferrofluid emulsions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1993, 122, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, F.; Braconnot, S.; Mondain-Monval, O.; Pichot, C.; Elaïssari, A. Colloidal and Physicochemical Characterization of Highly Magnetic O/W Magnetic Emulsions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2003, 24, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfester, K. Polyreactions in miniemulsions. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2001, 22, 896–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfester, K. Synthesis of Colloidal Particles in Miniemulsions. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2006, 36, 231–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kwon, H.J.; Shin, K.; Kim, J.; Yoo, R.-E.; Choi, S.H.; Soh, M.; Kang, T.; Han, S.I.; Hyeon, T. Multiplexible Wash-Free Immunoassay Using Colloidal Assemblies of Magnetic and Photoluminescent Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8448–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, F.; Mondain-Monval, O.; Pichot, C.; Elaissari, A. Highly Magnetic Latexes from Submicrometer Oil in Water Ferrofluid Emulsions. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 2642–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfester, K.; Mailander, V. Nanocapsules with specific targeting and release properties using miniemulsion polymerization. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, V.N.; Elsesser, M.T.; Pine, D.J. Dense Packing and Symmetry in Small Clusters of Microspheres. Science 2003, 301, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Chang, W.-S.; Kan, S.; Majetich, S.A.; Lee, G.U. Synthesis and Characterization of Paramagnetic Microparticles through Emulsion-Templated Free Radical Polymerization. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2516–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yang, D.; Hu, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, J.Q. Preparation of monodispersed hybrid nanospheres with high magnetite content from uniform Fe3O4 clusters. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 339, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Jensen, C.; Charity, N.; Towner, R.; Mao, C. Oil phase evaporation-induced self-assembly of hydrophobic nanoparticles into spherical clusters with controlled surface chemistry in an oil-in-water dispersion and comparison of behaviors of individual and clustered iron oxide nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 17724–17732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, C.; Page, L.; Kell, A.; Simard, B. Nanobeads Highly Loaded with Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles Prepared by Emulsification and Seeded-Emulsion Polymerization. Langmuir 2010, 26, 5388–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paquet, C.; de Haan, H.W.; Leek, D.M.; Lin, H.-Y.; Xiang, B.; Tian, G.; Kell, A.; Simard, B. Clusters of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles encapsulated in a hydrogel: A particle architecture generating a synergistic enhancement of the T2 relaxation. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3104–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, J.J.; Platt, M.; Kilinc, D.; Lee, G. Synthesis of superparamagnetic particles with tunable morphologies: The role of nanoparticle-nanoparticle interactions. Langmuir 2013, 29, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, J.K.; Deak, A.; Brougham, D.F. Nanoparticle Clusters: Assembly and Control Over Internal Order, Current Capabilities, and Future Potential. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5400–5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, R.; Socoliuc, V.; Crăciunescu, I.; Petran, A.; Paulus, A.; Franzreb, M.; Vasile, E.; Vékás, L. Magnetic microgels, a promising candidate for enhanced magnetic adsorbent particles in bioseparation: Synthesis, physicochemical characterization, and separation performance. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landfester, K.; Ramırez, L.P. Encapsulated magnetite particles for biomedical application. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2003, 15, S1345–S1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

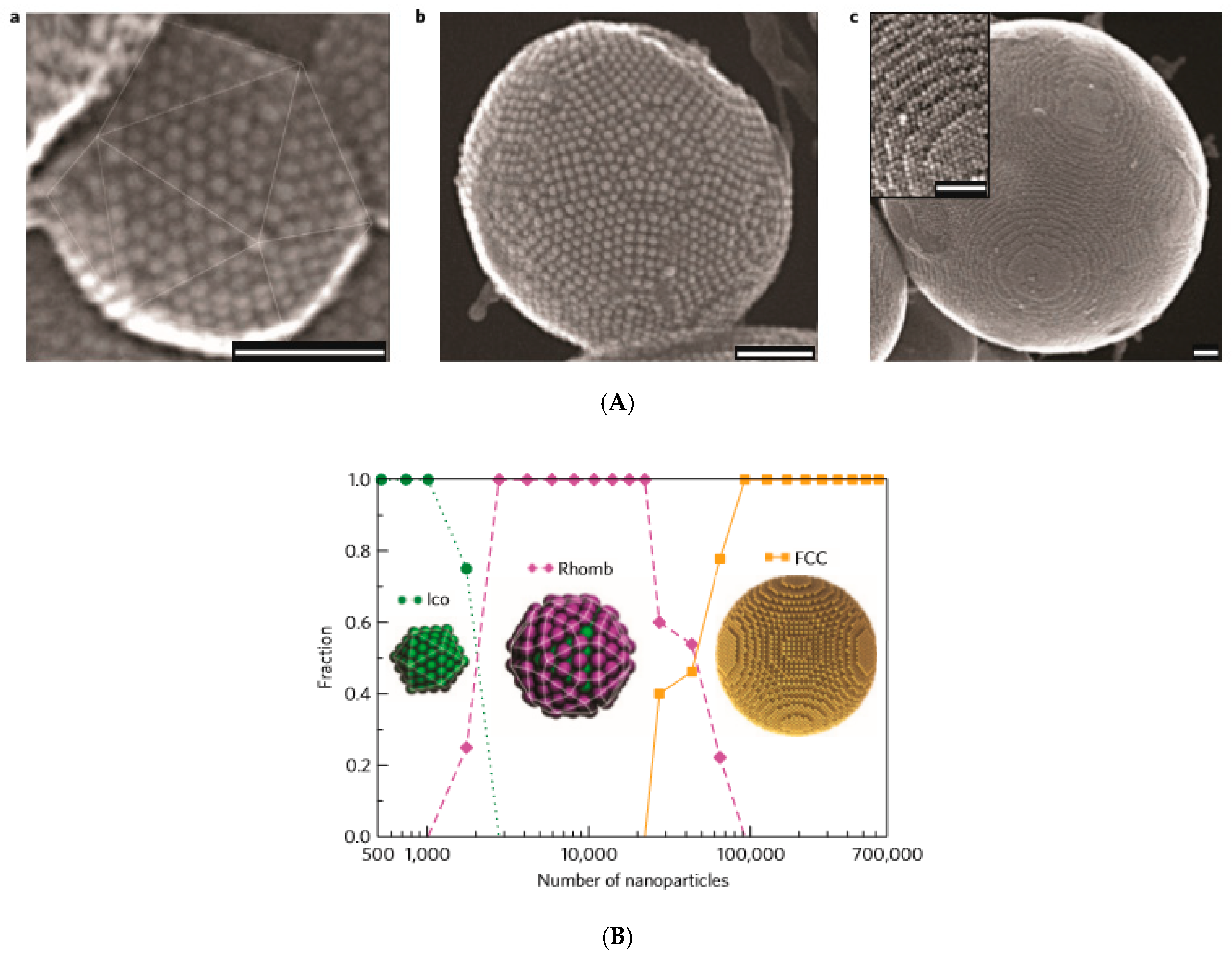

- Teich Erin, G.; van Anders, G.; Klotsa, D.; Dshemuchadse, J.; Sharon, C. Glotzer, Clusters of polyhedra in spherical confinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E669–E678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Amirshaghaghi, A.; Huang, D.; Miller, J.; Stein, J.M.; Busch, T.M.; Cheng, Z.; Tsourkas, A. Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX)-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) Nanoclusters for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, T.R.; Lansalot, M.; Bourgeat-Lami, E. Polymer-encapsulation of iron oxide clusters using macroRAFT block copolymers as stabilizers: Tuning of the particle morphology and surface functionalization. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.-H.; Liao, B.-J.; Chiang, C.-S.; Chen, P.-J.; Chen, I.-W.; Chen, S.-Y. Core-Shell Nanocapsules Stabilized by Single-Component Polymer and Nanoparticles for Magneto-Chemotherapy/Hyperthermia with Multiple Drugs. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3627–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu, R.; Craciunescu, I.; Nan, A. Magnetic Microgels: Synthesis and Characterization. In Upscaling of Bio-Nano-Processes, Selective Bioseparation by Magnetic Particles; Nirschl, H., Keller, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 57–76. ISBN 978-3-662-43899-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, I.; Hsu, C.-C.; Gärtner, M.; Müller, C.; Overton, T.W.; Thomas, O.R.T.; Franzreb, M. Continuous protein purification using functionalized magnetic nanoparticles in aqueous micellar two-phase systems. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1305, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshaghaghi, A.; Yan, L.; Miller, J.; Daniel, Y.; Stein, J.M.; Busch, T.M.; Cheng, Z.; Tsourkas, A. Chlorin e6-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) Nanoclusters as a Theranostic Agent for Dual Mode Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommertune, J.; Sugunan, A.; Ahniyaz, A.; Stjernberg Bejhed, R.; Sarwe, A.; Johansson, C.; Balceris, C.; Ludwig, F.; Posth, O.; Fornara, A. Polymer/Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Composites—A Straight Forward and Scalable Synthesis Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 19752–19768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilán, H.; Kowalski, A.; Heinke, D.; Sugunan, A.; Sommertune, J.; Varón, M.; Bogart, L.K.; Posth, O.; Zeng, L.; González-Alonso, D.; et al. Puerto Morales. Colloidal Flower-Shaped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis Strategies and Coatings. Part. Part. Syst. Char. 2017, 34, 1700094. [Google Scholar]

- de Nijs, B.; Dussi, S.; Smallenburg, F.; Meeldijk, J.D.; Groenendijk, D.J.; Filion, L.; Imhof, A.; van Blaaderen, A.; Dijkstra, M. Entropy-driven formation of large icosahedral colloidal clusters by spherical confinement. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hermes, M.; Kotni, R.; Wu, Y.; Tasios, N.; Liu, Y.; de Nijs, B.; van der Wee, E.B.; Murray, C.B.; Dijkstra, M.; et al. Interplay between spherical confinement and particle shape on the self-assembly of rounded cubes. Nat. Comm. 2018, 9, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzard, J.; Platt, M.; Lee, G.U. M13 Bacteriophage-Activated Superparamagnetic Beads for Affinity Separation. Small 2012, 8, 2403–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-H.; Gao, X. Nanocomposites with Spatially Separated Functionalities for Combined Imaging and Magnetolytic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 7234–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, V.; Lorenz, M.; Kilian Weiss, C.K.; Schrezenmeier, H.; Landfester, K.; Mailander, V. Synthesis and biomedical applications of functionalized fluorescent and magnetic dual reporter nanoparticles as obtained in the miniemulsion process. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S2581–S2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M.; Musyanovych, A.; Landfester, K. Fluorescent Superparamagnetic Polylactide Nanoparticles by Combination of Miniemulsion and Emulsion/Solvent Evaporation Techniques. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2009, 210, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

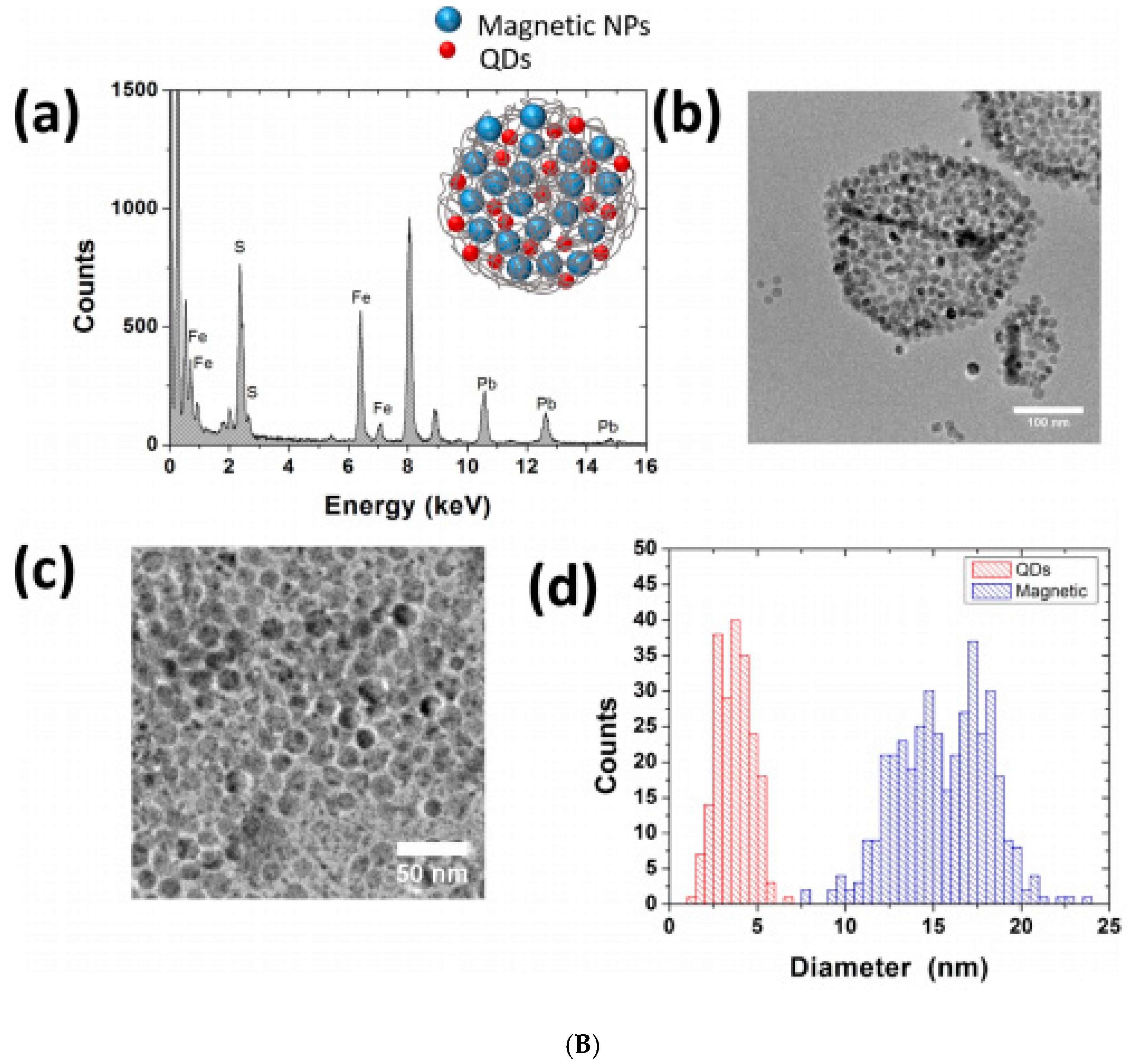

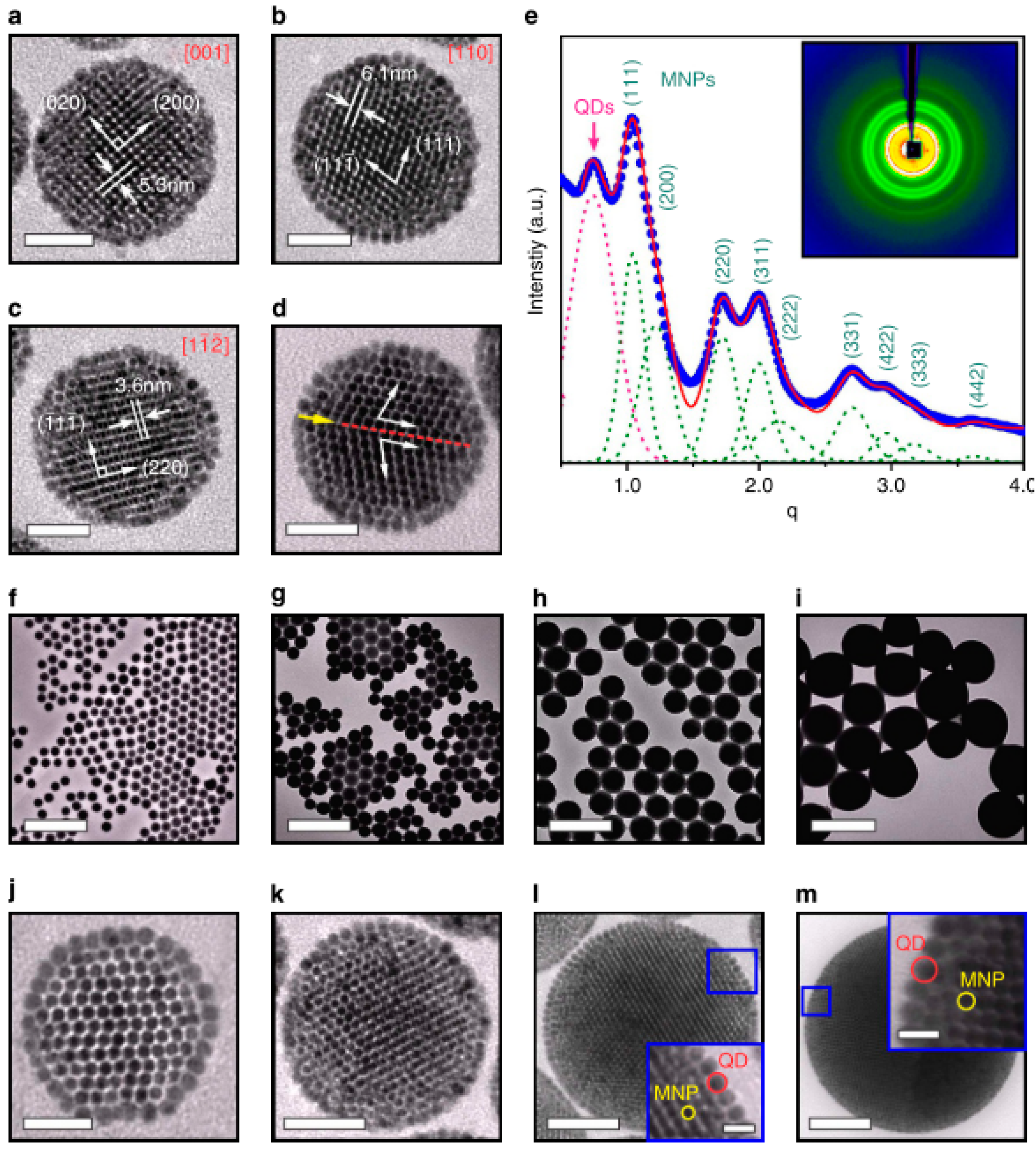

- Chen, O.; Riedemann, L.; Etoc, F.; Herrmann, H.; Coppey, M.; Barch, M.; Farrar, C.T.; Zhao, J.; Bruns, O.T.; Wei, H.; et al. Magneto-Fluorescent Core-Shell Supernanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortgies, D.H.; de la Cueva, L.; del Rosal, B.; Sanz-Rodríguez, F.; Fernandez, N.; Iglesias-de la Cruz, C.; Salas, G.; Cabrera, D.; Teran, F.J.; Jaque, D.; et al. In Vivo Deep Tissue Fluorescence and Magnetic Imaging Employing Hybrid Nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Skripka, A.; Tabatabaei, M.S.; Hong, S.H.; Ren, F.; Benayas, A.; Oh, Y.K.; Martel, S.; Liu, X.; Vetrone, F.; et al. Multifunctional Self-Assembled Supernanoparticles for Deep-Tissue Bimodal Imaging and Amplified Dual-Mode Heating Treatment. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppellaros, G.; Kolokithas-Ntoukas, A.; Polakova, K.; Tucek, J.; Zboril, R.; Loudos, G.; Fragogeorgi, E.; Diwoky, C.; Tomankova, K.; Avgoustakis, K.; et al. Theranostics of Epitaxially Condensed Colloidal Nanocrystal Clusters, through a Soft iomineralization Route. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2062–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materia, M.E.; Guardia, P.; Sathya, A.; Leal, M.P.; Marotta, R.; Di Corato, R.; Teresa Pellegrino, T. Mesoscale Assemblies of Iron Oxide Nanocubes as Heat Mediators and Image Contrast Agents. Langmuir 2015, 31, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculaes, D.; Lak, A.; Anyfantis, G.C.; Marras, S.; Laslett, O.; Avugadda, S.K.; Cassani, M.; Serantes, D.; Hovorka, O.; Chantrell, R.; et al. Asymmetric Assembling of Iron Oxide Nanocubes for Improving Magnetic Hyperthermia Performance. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 12121–12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V.P. Recent Advances with Liposomes as Pharmaceutical carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, R.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Liposomes as “smart” pharmaceutical nanocarriers. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 4026–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, E.; Reimhult, E. Nanoparticle actuated hollow drug delivery vehicles. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, M.; Joniau, M. Magnetoliposomes. Formation and structural characterization. Eur. Biophys. J. 1988, 15, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, S.J.H.; Hodenius, M.; De Cuyper, M. Magnetoliposomes: Versatile innovative nanocolloids for use in biotechnology and biomedicine. Nanomedicine 2009, 4, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhaylov, G.; Mikac, U.; Magaeva, A.A.; Itin, V.I.; Naiden, E.P.; Psakhye, I.; Babes, L.; Reinheckel, T.; Peters, C.; Zeiser, R.; et al. Ferri-liposomes as an MRI-visible drug-delivery system for targeting tumours and their microenvironment. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, E.R.; Ferreira, F.S.; Santos Junior, J.L.; Campello, J.C.; Socolovsky, L.M.; Lima, E.M.; Bakuzis, A.F. Nanoparticle agglomerates in magnetoliposomes. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 045103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Corato, R.; Espinosa, A.; Lartigue, L.; Tharaud, M.; Chat, S.; Pellegrino, T.; Ménager, C.; Gazeau, F.; Wilhelm, C. Magnetic hyperthermia efficiency in the cellular environment for different nanoparticle designs. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 6400–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiki, Y.; Namiki, T.; Yoshida, H.; Ishii, Y.; Tsubota, A.; Koido, S.; Nariai, K.; Mitsunaga, M.; Yanagisawa, S.; Kashiwagi, H.; et al. A novel magnetic crystal-lipid nanostructure for magnetically guided in vivo gene delivery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calucci, L.; Grillone, A.; Redolfi Riva, E.; Mattoli, V.; Ciofani, G.; Forte, C. NMR Relaxometric Properties of SPION-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciello, M.; Pellico, J.; Fernandez-Barahona, I.; Herranz, F.; Ruiz-Cabello, J.; Filice, M. Recent advances in the preparation and application of multifunctional iron oxide and liposome-based nanosystems for multimodal diagnosis and therapy. Interface Focus 2016, 6, 20160055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D. Interfaces and the driving force of hydrophobic assembly. Nature 2005, 437, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.E.; Rosenberg, K.J.; Israelachvili, J. Recent progress in understanding hydrophobic interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15739–15746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-L.; Yang, J.-J.; ZhuGe, D.-L.; Lin, M.-T.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Jin, B.-H.; Tong, M.-Q.; Shen, B.-X.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, Y.-Z. Glioma-Targeted Delivery of a Theranostic Liposome Integrated with Quantum Dots, Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide, and Cilengitide for Dual-Imaging Guiding Cancer Surgery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1701130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoka, F., Jr.; Papahadjopoulos, D. Procedure for preparation of liposomes with large internal aqueous space and high capture by reverse-phase evaporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4194–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, E.; Kohlbrecher, J.; Muller, E.; Schweizer, T.; Textor, M.; Reimhult, E. Triggered Release from Liposomes through Magnetic Actuation of Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Containing Membranes. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleul, R.; Thiermann, R.; Marten, G.U.; House, M.J.; St Pierre, T.G.; Häfeli, U.O.; Maskos, M. Continuously manufactured magnetic polymersomes-a versatile tool (not only) for targeted cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 11385–11393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, M.; Socoliuc, V.; Doroftei, F.; Ursu, E.-L.; Aflori, M.; Vékás, L.; Simionescu, B.C. Calcium Carbonate−Magnetite−Chondroitin Sulfate Composite Microparticles with Enhanced pH Stability and Superparamagnetic Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphew, D.; Chakrabarti, D. Clusters of anisotropic colloidal particles: From colloidal molecules to supracolloidal structures. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 30, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.G.D.; Veloso, S.R.S.; Castanheira, E.M.S. Shape Anisotropic Iron Oxide-Based Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, M.; Gradzielski, M. Droplets, Evaporation and a Superhydrophobic Surface: Simple Tools for Guiding Colloidal Particles into Complex Materials. Gels 2017, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, M.; Papadopoulos, P.; Gradzielski, M. Understanding the Formation of Anisometric Supraparticles: A Mechanistic Look inside Droplets Drying on a Superhydrophobic Surface. Langmuir 2016, 32, 6902–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Butt, H.-J.; Landfester, K.; Bannwarth, M.B.; Wooh, S.; Thérien-Aubin, H. Shaping the Assembly of Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3015–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Seeger, S. Superamphiphobic surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2784–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, M.; Spiering, V.J.; Velev, O.D.; Gradzielski, M. Controlled Formation of Patchy Anisometric Fumed Silica Supraparticles in Droplets on Bent Superhydrophobic Surfaces. Part. Part. Syst. Char. 2017, 34, 1600176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, H.; Ferretti, A.M.; Innocenti, C.; Fidecka, K.; Licandro, E.; Sangregorio, C.; Maggioni, D. An Approach for Magnetic Halloysite Nanocomposite with Selective Loading of Superparamagnetic Magnetite Nanoparticles in the Lumen. Inorg. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.; Baburin, I.A.; Sturm, S.; Kvashnina, K.; Rossberg, A.; Pietsch, T.; Andreev, S.; Sturm, E.; Cölfen, H. Self-Assembled Magnetite Mesocrystalline Films: Toward Structural Evolution from 2D to 3D Superlattices. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1600431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, S.; Makovec, D. Magnetic Assembly of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Clusters into Nanochains and Nanobundles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9700–9707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannwarth, M.B.; Kazer, S.W.; Ulrich, S.; Glasser, G.; Crespy, D.; Landfester, K. Well-Defined Nanofibers with Tunable Morphology from Spherical Colloidal Building Blocks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10107–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, M.B.; Utech, S.; Ebert, S.; Weitz, D.A.; Crespy, D.; Landfester, K. Colloidal Polymers with Controlled Sequence and Branching Constructed from Magnetic Field Assembled Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2720–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannwarth, M.B.; Camerlo, A.; Ulrich, S.; Jakob, G.; Fortunato, G.; Rossi, R.M.; Boesel, L.F. Ellipsoid-Shaped Superparamagnetic Nanoclusters through Emulsion Electrospinning. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3758–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S.; Gamella, M.; Serafín, V.; Pedrero, M.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Magnetic Janus Particles for Static and Dynamic (Bio) Sensing. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Choo, E.S.G.; Ahmed, A.S.; Zhao, L.Y.; Yang, Y.; Ramanujan, R.V.; Xue, J.M.; Fan, D.D.; Fan, H.M.; Ding, J. Magnetic nanoparticle-loaded polymer nanospheres as magnetic hyperthermia agents. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattuada, M.; Hatton, T.A. Preparation and Controlled Self-Assembly of Janus Magnetic Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12878–12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintzheimer, S.; Granath, T.; Eppinger, A.; Goncalves, M.R.; Karl Mandel, K. A code with a twist: Supraparticle microrod composites with direction dependent optical properties as anti-counterfeit labels. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1510–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müssig, S.; Granath, T.; Schembri, T.; Fidler, F.; Haddad, D.; Hiller, K.-H.; Wintzheimer, S.; Mandel, K. Anisotropic Magnetic Supraparticles with a Magnetic Particle Spectroscopy Fingerprint as Indicators for Cold-Chain Breach. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 4698–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis-Bröhl, K.; Vreeland, E.C.; Gomez, A.; Huber, D.L.; Saini, A.; Wolff, M.; Maranville, B.B.; Brok, E.; Krycka, K.L.; Dura, J.A.; et al. Self-Assembled Layering of Magnetic Nanoparticles in a Ferrofluid on Silicon Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 5050–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis-Bröhl, K.; Saini, A.; Wolff, M.; Dura, J.A.; Maranville, B.B.; Borchers, J.A. Self-Assembly of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids on Different Templates Investigated by Neutron Reflectometry. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kötitz, R.; Weitschies, W.; Trahms, L.; Semmler, W. Investigation of Brownian and Néel relaxation in magnetic fluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1999, 201, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, S.; Chen, S.; Fang, H.; Song, Y.; Duan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, H. Nanofibers with diameter below one nanometer from electrospinning. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 4794–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.-E.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on electrospinning design and nanofibre assemblies. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, R89–R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persano, L.; Camposeo, A.; Tekmen, C.; Pisignano, D. Industrial Upscaling of Electrospinning and Applications of Polymer Nanofibers: A Review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013, 298, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Encroachment of Traditional Electrospinning. In Electrospinning–Basic Research to Commercialization; Thomas, S., Ghosal, K., Kny, E., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018; pp. 24–54. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi, J.; Reneker, D.H. Electrospinning Process and Applications of Electrospun Fibers. J. Electrostat. 1995, 35, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reneker, D.H.; Yarin, A.L.; Zussman, E.; Xu, H. Electrospinning of Nanofibers from Polymer Solutions and Melts. In Advances in Applied Mechanics; Aref, H., van der Giessen, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 41, pp. 43–195, 345–346. [Google Scholar]

- Papaparaskeva, G.; Dinev, M.M.; Krasia-Christoforou, T.; Porav, S.A.; Turcu, R.P.; Balanean, F.; Socoliuc, V.M. White magnetic paper with zero remanence based on electrospun cellulose microfibers doped with iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 1, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panteli, S.; Savva, I.; Efstathiou, M.; Vékás, L.; Marinica, O.M.; Krasia-Christoforou, T.; Pashalidis, I. β-Ketoester-Functionalized Magnetoactive Electrospun Polymer Fibers as Eu(III) Adsorbents. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Krekos, G.; Taculescu, A.; Marinica, O.; Vékás, L.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Fabrication and characterization of magnetoresponsive electrospun nanocomposite membranes based on methacrylic random copolymers and magnetite nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 578026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarik, I.; Pospiskova, K.; Baldikova, E.; Savva, I.; Vékás, L.; Marinica, O.; Tanasa, E.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Fabrication and Bioapplications of Magnetically Modified Chitosan-based Electrospun Nanofibers. Electrospinning 2018, 2, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Marinica, O.; Papatryfonos, C.A.; Vékás, L.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Evaluation of electrospun polymer–Fe3O4 nanocomposite mats in malachite green adsorption. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 16484–16496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Odysseos, A.D.; Evaggelou, L.; Marinica, O.; Vasile, E.; Vékás, L.; Sarigiannis, Y.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Fabrication, Characterization, and Evaluation in Drug Release Properties of Magnetoactive Poly(ethylene oxide)-Poly(L-lactide) Electrospun Membranes. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 4436–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, I.; Constantinou, D.; Marinica, O.; Vasile, E.; Vékás, L.; Krasia-Christoforou, T. Fabrication and characterization of superparamagnetic poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)/poly(L-lactide)/Fe3O4 electrospun membranes. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 352, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, A.; Kralj, S.; Karagiorgis, X.; Savva, I.; Loizides, E.; Panagi, M.; Krasia-Christoforou, T.; Riziotis, C. Multifunctional Gas and pH Fluorescent Sensors Based on Cellulose Acetate Electrospun Fibers Decorated with Rhodamine B-Functionalised Core-Shell Ferrous Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, B.; Williams, G.R.; Branford-White, C.; Quan, J.; Nie, H.; Zhu, L. Self-assembled core-shell Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles from electrospun fibers. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 3058–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskov, K.E.; Atkinson, J.E.; Bronstein, L.M.; Spontak, R.J. Magnetic field-induced alignment of nanoparticles in electrospun microfibers. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 4603–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, W.H. Supramolecular self-assemblies as functional nanomaterials, Supramolecular Assembly of Nanoparticles at Liquid–Liquid Interfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5172–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasia-Christoforou, T. Organic-inorganic polymer hybrids: Synthetic strategies and applications. In Hybrid and Hierarchical Composite Materials; Changsoo, K., Sano, T., Randow, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 11–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, J.; Guimaraes, P.P.G.; Ahn, H.M.; Jung, B.-K.; Hu, Q.; McHugh, K.; Mitchell, M.J.; Yun, C.-O.; Langer, R.; Jaklenec, A. Chiral Supraparticles for Controllable Nanomedicine. Adv. Mater. 2019, 32, 1903878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrouki, D.; Baudry, J.; Pine, D.; Chaikin, P.; Bibette, J. Chiral colloidal clusters. Nature 2008, 455, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Chan, H.; Baskin, A.; Gelman, E.; Repnin, N.; Kral, P.; Klajn, R. Self-Assembly of Magnetite Nanocubes into Helical Superstructures. Science 2014, 345, 149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pumera, M. Fabrication of Micro/Nanoscale Motors. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8704–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

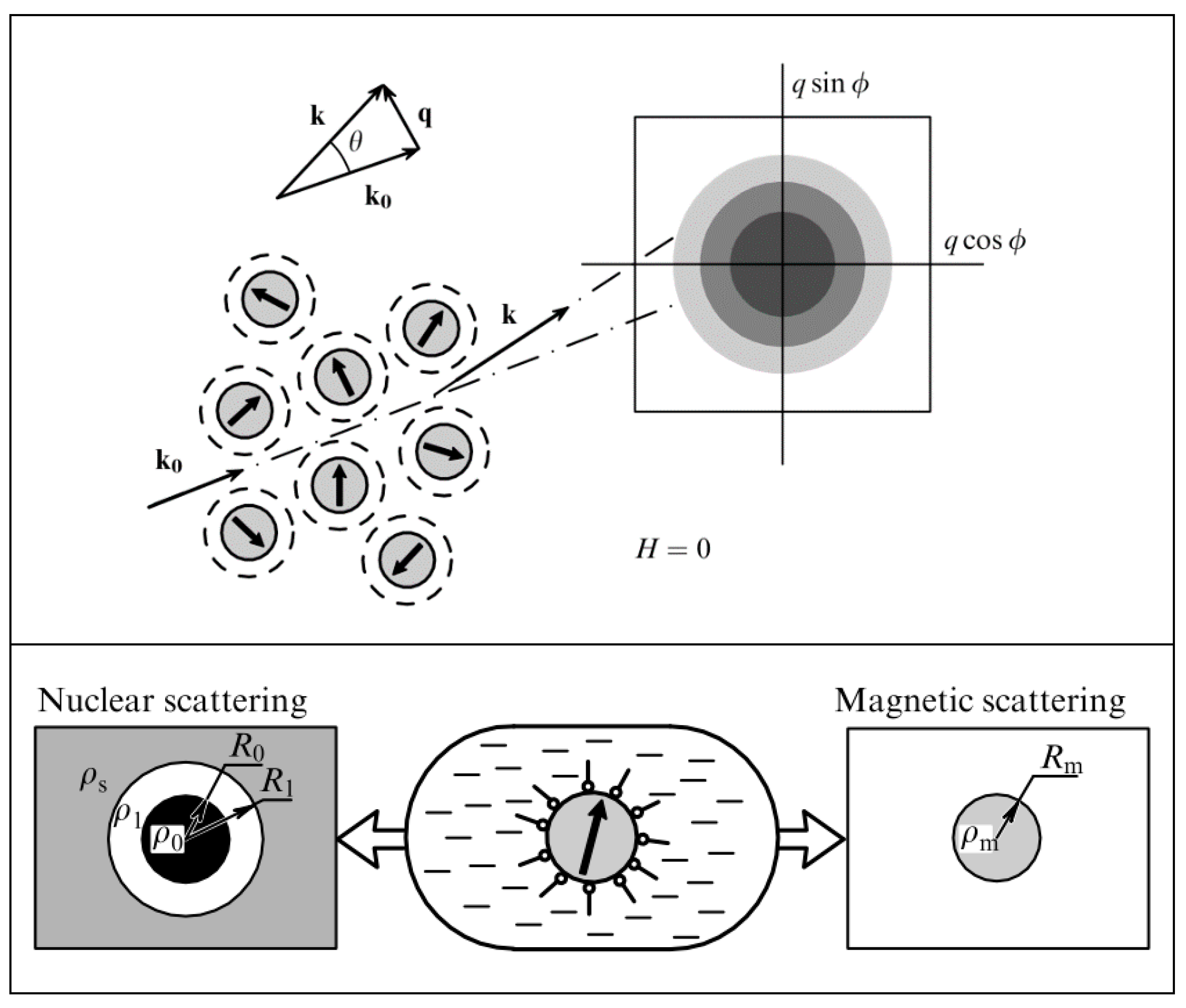

- Suter, M. Photopatternable Superparamagnetic Nanocomposite for the Fabrication of Microstructures. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Suter, M.; Zhang, L.; Siringil, E.C.; Peters, C.; Luehmann, T.; Ergeneman, O.; Peyer, K.E.; Nelson, B.J.; Hierold, C. Superparamagnetic microrobots: Fabrication by two-photon polymerization and biocompatibility. Biomed. Microdevices 2013, 15, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, M.; Smith, P.J.; Schubert, U.S. Inkjet printing as a deposition and patterning tool for polymers and inorganic particles. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Kuang, M.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Printing 1D Assembly Array of Single Particle Resolution for Magnetosensing. Small 2018, 14, 1800117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Song, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, N. Magnetic assembly-mediated enhancement of differentiation of mouse bone marrow cells cultured on magnetic colloidal assemblies. Sci. Rep. 2015, 4, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavacoli, J.W.; Bauer, P.; Fermigier, M.; Bartolo, D.; Heuvingh, J.; du Roure, O. The fabrication and directed self-assembly of micron-sized superparamagnetic non-spherical particles. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 9103–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzyna, P.A.; Skajaa, T.; Gianella, A.; Cormode, D.P.; Samber, D.D.; Dickson, S.D.; Chen, W.; Griffioen, A.F.; Fayad, Z.A.; Mulder, W.J.M. Iron oxide core oil-in-water emulsions as a multifunctional nanoparticle platform for tumor targeting and imaging. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6947–6954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tilborg, G.A.F.; Cormode, D.P.; Jarzyna, P.A.; van Der Toorn, A.; van Der Pol, S.M.A.; van Bloois, L.; Fayad, Z.A.; Storm, G.; Mulder, W.J.M.; de Vries, H.E.; et al. Nanoclusters of Iron Oxide: Effect of Core Composition on Structure, Biocompatibility, and Cell Labeling Efficacy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.D.; Choi, C.; Khamwannah, J.; Jin, S. Magnetically Vectored Delivery of Cancer Drug Using Remotely On–Off Switchable NanoCapsules. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Giri, J.; Rieken, F.; Koch, C.; Mykhaylyk, O.; Döblinger, M.; Banerjee, R.; Bahadur, D.; Plank, C. Targeted temperature sensitive magnetic liposomes for thermo-chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Yu, J.C.; Zhu, X.-M.; Chan, K.M.; Wang, Y.-X.J. Ultra-fast method to synthesize mesoporous magnetite nanoclusters as highly sensitive magnetic resonance probe. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 379, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Qiao, S.Z.; Cheng, L.; Yan, Z.; Lu, G.Q. Fabrication of a magnetic helical mesostructured silica rod. Nanotechnology 2008, 435608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.; Miyajima, D.; Niwa, T.; Taguchi, H.; Aida, T. Tailoring Micrometer-Long High-Integrity 1D Array of Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles in a Nanotubular Protein Jacket and Its Lateral Magnetic Assembling Behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4658–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etheridge, M.L.; Hurley, K.R.; Zhang, J.; Jeon, S.; Ring, H.L.; Hogan, C.; Haynes, C.L.; Garwood, M.; Bischof, J.C. Accounting for biological aggregation in heating and imaging of magnetic nanoparticles. Technology 2014, 2, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; de la Cueva, L.; Moros, M.; Mazarío, E.; de Bernardo, S.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Puerto Morales, M.; Salas, G. Aggregation effects on the magnetic properties of iron oxide colloids. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacri, J.C.; Boué, F.; Cabuil, V.; Perzynski, R. Ionic Ferrofluids: Intraparticle and Interparticle Correlations from Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1993, 80, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E.; Cabuil, V.; Boué, F.; Perzynski, R. Structural Analogy between Aqueous and Oily Magnetic Fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 7147–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Dubois, E.; Mériguet, G.; Wandersman, E.; Garamus, V.M.; Feoktystov, A.V.; Perzynski, R. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Analysis of a Water-Based Magnetic Fluid with Charge Stabilization: Contrast Variation and Scattering of Polarized Neutrons. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

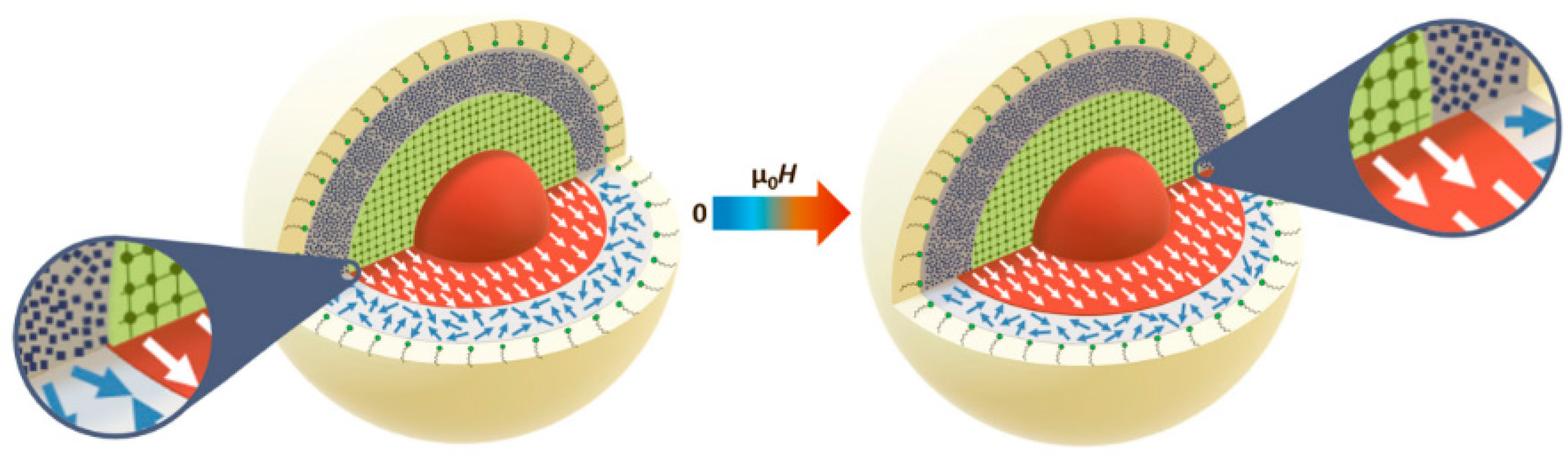

- Avdeev, M.V.; Aksenov, V.L. Small-angle neutron scattering in structure research of magnetic fluids. Phys. Uspekhi 2010, 53, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

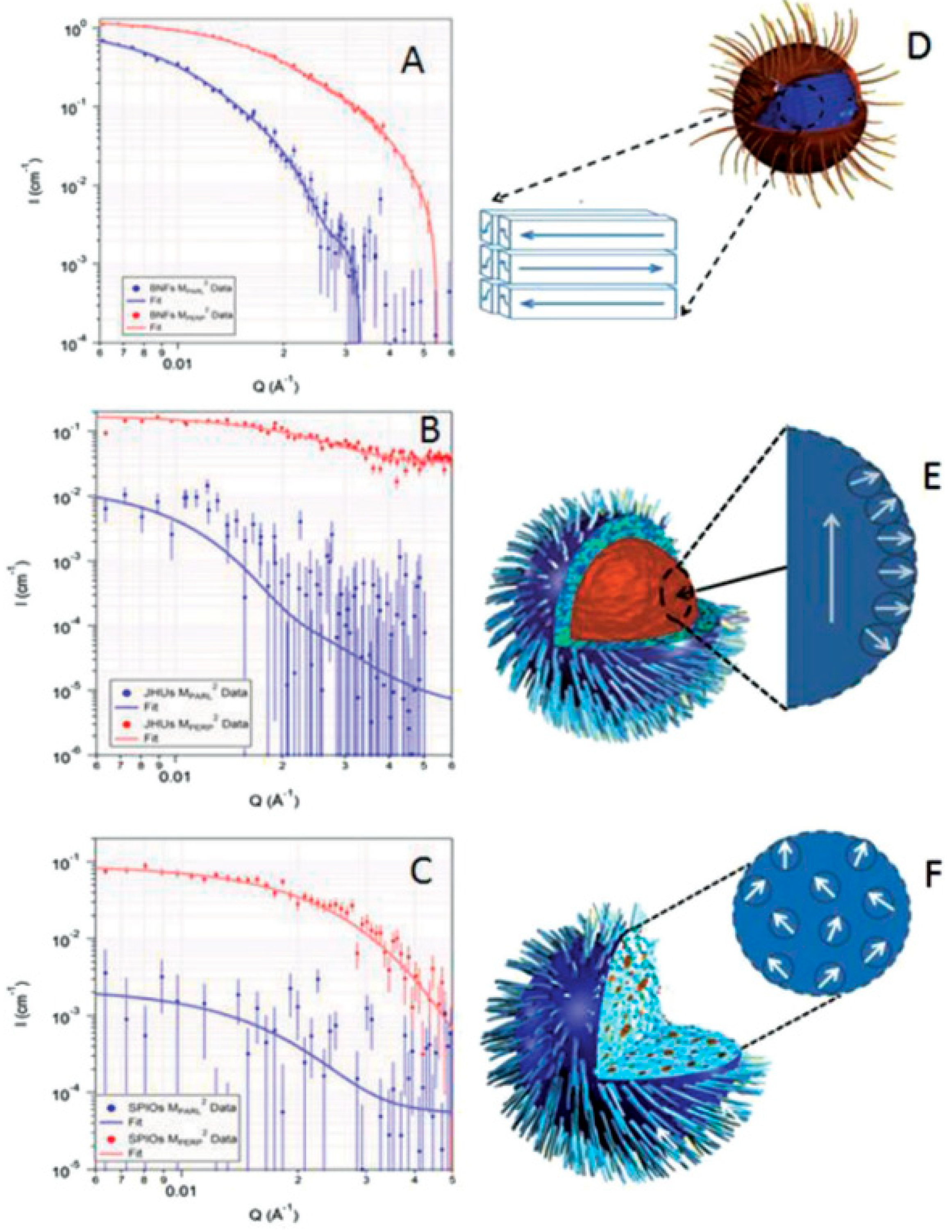

- Mühlbauer, S.; Honecker, D.; Périgo, É.A.; Bergner, F.; Disch, S.; Heinemann, A.; Erokhin, S.; Berkov, D.; Leighton, C.; Eskildsen, M.R.; et al. Magnetic Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2019, 91, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeau, F.; Dubois, E.; Bacri, J.C.; Boué, F.; Cebers, A.; Perzynski, R. Anisotropy of the Structure Factor of Magnetic Fluids under a Field Probed by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmasfluidsand Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 2002, 65, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mériguet, G.; Cousin, F.; Dubois, E.; Boué, F.; Cebers, A.; Farago, B.; Perzynski, R. What Tunes the Structural Anisotropy of Magnetic Fluids under a Magnetic Field? J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 4378–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

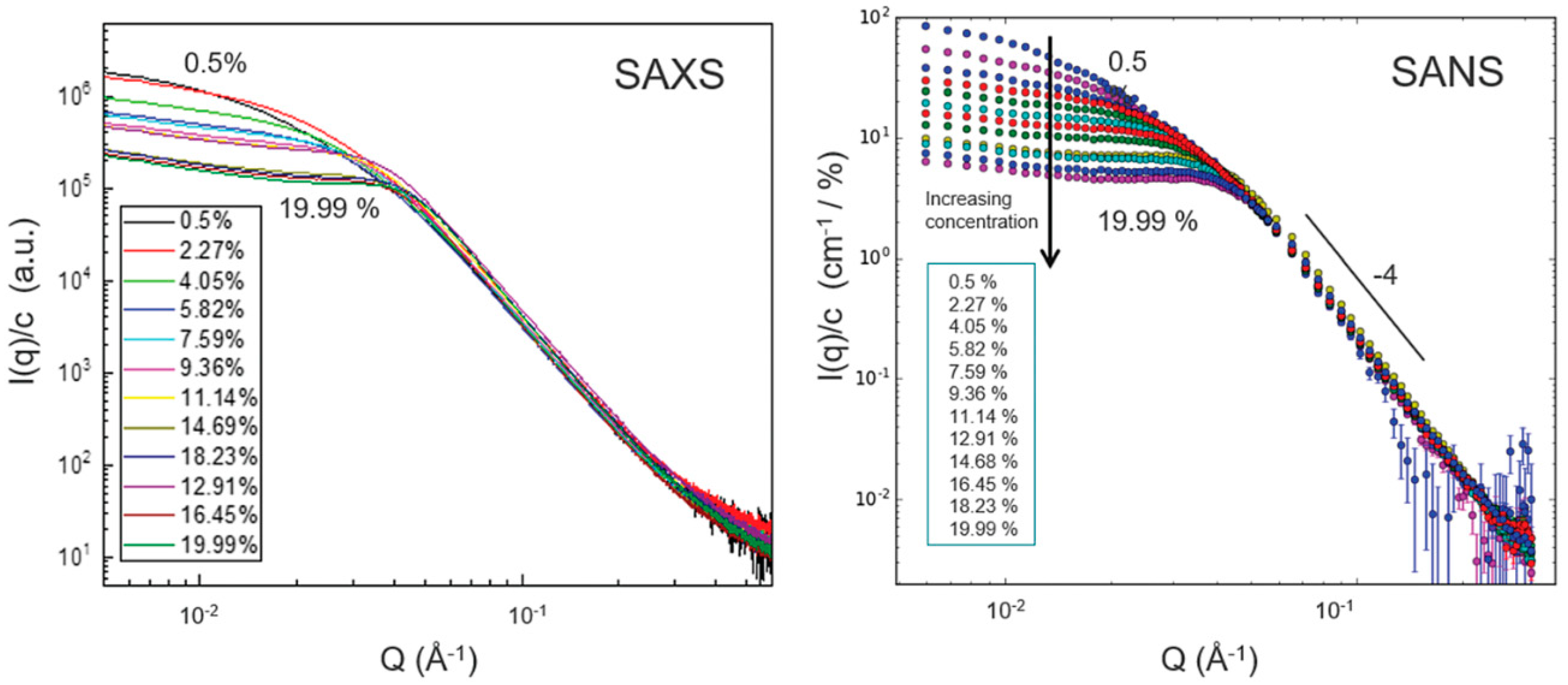

- Vasilescu, C.; Latikka, M.; Knudsen, K.D.; Garamus, V.M.; Socoliuc, V.; Turcu, R.; Tombácz, E.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Ras, R.H.A.; Vékás, L. High Concentration Aqueous Magnetic Fluids: Structure, Colloidal Stability, Magnetic and Flow Properties. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 6648–6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmann, A.; Hoell, A.; Kammel, M.; Boesecke, P. Field-Induced Pseudocrystalline Ordering in Concentrated Ferrofluids. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmasfluidsand Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 2003, 68, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagornyi, A.V.; Socoliuc, V.; Petrenko, V.I.; Almasy, L.; Ivankov, O.I.; Avdeev, M.V.; Bulavin, L.A.; Vékás, L. Structural Characterization of Concentrated Aqueous Ferrofluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 501, 166445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, V.I.; Aksenov, V.L.; Avdeev, M.V.; Bulavin, L.A.; Rosta, L.; Vékás, L.; Garamus, V.M.; Willumeit, R. Analysis of the Structure of Aqueous Ferrofluids by the Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Method. Phys. Solid State 2010, 52, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, V.I.; Artykulnyi, O.P.; Bulavin, L.A.; Almásy, L.; Garamus, V.M.; Ivankov, O.I.; Grigoryeva, N.A.; Vékás, L.; Kopcansky, P.; Avdeev, M.V. On the Impact of Surfactant Type on the Structure of Aqueous Ferrofluids. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 541, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Feoktystov, A.V.; Kopcansky, P.; Lancz, G.; Garamus, V.M.; Willumeit, R.; Timko, M.; Koneracka, M.; Zavisova, V.; Tomasovicova, N.; et al. Structure of Water-Based Ferrofluids with Sodium Oleate and Polyethylene Glycol Stabilization by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering: Contrast-Variation Experiments. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2010, 43, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Petrenko, V.I.; Feoktystov, A.V.; Gapon, I.V.; Aksenov, V.L.; Vékás, L.; Kopčanský, P. Neutron Investigations of Ferrofluids. Ukr. J. Phys. 2015, 60, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakutna, D.; Nižňanský, D.; Barnsley, L.C.; Babcock, E.; Salhi, Z.; Feoktystov, A.; Honecker, D.; Disch, S. Field Dependence of Magnetic Disorder in Nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. X 2020, 10, 0310190. [Google Scholar]

- Hoell, A.; Müller, R.; Wiedenmann, A.; Gawalek, W. Core-Shell and Magnetic Structure of Barium Hexaferrite Fluids Studied by SANS. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002, 252, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kons, C.; Huong Phan, M.; Srikanth, H.; Arena, D.A.; Nemati, Z.; Borchers, J.A.; Krycka, K.L. Investigating Spin Coupling across a Three-Dimensional Interface in Core/Shell Magnetic Nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brok, E.; Krycka, K.L.; Vreeland, E.C.; Gomez, A.; Huber, D.L.; Majkrzak, C.F. Phase-Sensitive Small-Angle Neutron Scattering Experiment. J. Phys. Commun. 2018, 2, 095018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdick, S.D.; Abdelgawad, A.; Moya, C.; Mesbahi-Vasey, S.; Kepaptsoglou, D.; Lazarov, V.K.; Evans, R.F.L.; Meilak, D.; Skoropata, E.; Van Lierop, J.; et al. Spin Canting across Core/Shell Fe3O4/MnxFe3-XO4 Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Feoktystov, A.; Pipich, V.; Sousai Appavou, M.; Su, Y.; Feng, E.; Jin, W.; Brückel, T. Field-Induced Self-Assembly of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Investigated Using Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 18541–18550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Krycka, K.L.; Borchers, J.A.; Desautels, R.D.; Van Lierop, J.; Huls, N.F.; Jackson, A.J.; Gruettner, C.; Ivkov, R. Internal Magnetic Structure of Nanoparticles Dominates Time-Dependent Relaxation Processes in a Magnetic Field. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 4300–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersweiler, M.; Gavilan Rubio, H.; Honecker, D.; Michels, A.; Bende, P. The Benefits of a Bayesian Analysis for the Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 435704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral-Coral, D.F.; Mera-Córdoba, J.A. Applying SAXS to Study the Structuring of Fe3O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles in Colloidal Suspensions. Dyna (Colomb.) 2019, 86, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Paula, F.L.D.O. SAXS Analysis of Magnetic Field Influence on Magnetic Nanoparticle Clusters. Condens. Matter 2019, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

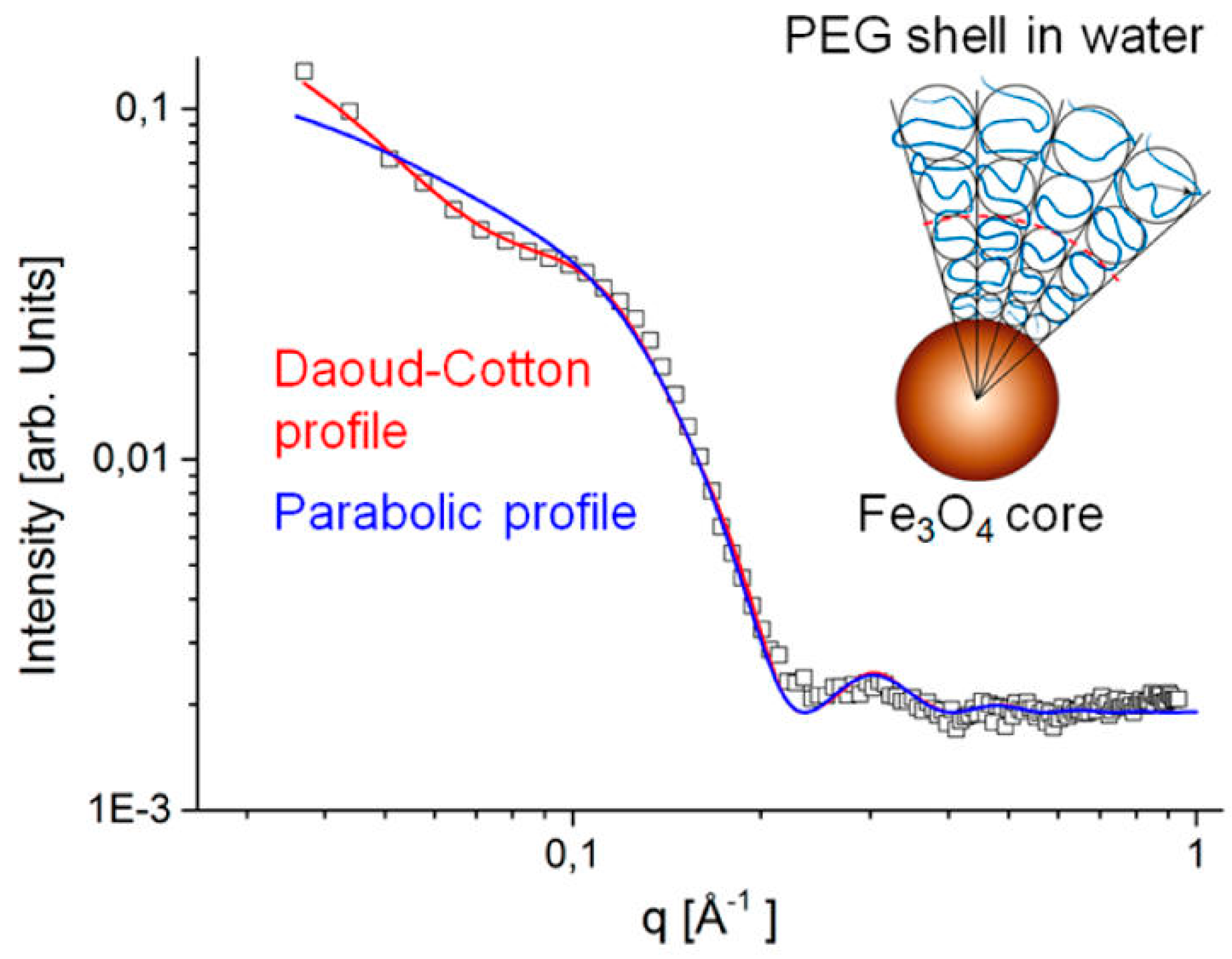

- Grünewald, T.A.; Lassenberger, A.; Van Oostrum, P.D.J.; Rennhofer, H.; Zirbs, R.; Capone, B.; Vonderhaid, I.; Amenitsch, H.; Lichtenegger, H.C.; Reimhult, E. Core−Shell Structure of Monodisperse Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Grafted Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Studied by Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering. Chem. Mater 2015, 27, 4763–4771. [Google Scholar]

- Daoud, M.; Cotton, J.P. Star-shaped polymers: A model for the conformation and its concentration dependence. J. Phys. (Paris) 1982, 43, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagornyi, A.V.; Petrenko, V.I.; Avdeev, M.V.; Yelenich, O.V.; Solopan, S.O.; Belous, A.G.; Gruzinov, A.Y.; Ivankov, O.I.; Bulavin, L.A. Structural Aspects of Magnetic Fluid Stabilization in Aqueous Agarose Solutions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 431, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, P.; Bogart, L.K.; Posth, O.; Szczerba, W.; Rogers, S.E.; Castro, A.; Nilsson, L.; Zeng, L.J.; Sugunan, A.; Sommertune, J.; et al. Structural and Magnetic Properties of Multi-Core Nanoparticles Analysed Using a Generalised Numerical Inversion Method. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, W.; Costo, R.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; del Puerto Morales, M.; Thünemann, A.F. SAXS Analysis of Single-and Multi-Core Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2017, 50, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, P.; Honecker, D.; Fernández Barquín, L. Supraferromagnetic correlations in clusters of magnetic nanoflowers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 115, 132406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.M.; Hilljegerdes, J.; Odenbach, S.; Wiedenmann, A. The Microstructure of Ferrofluids and Their Rheological Properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 18, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, L.M.; Odenbach, S. Investigation of the Microscopic Reason for the Magnetoviscous Effect in Ferrofluids Studied by Small Angle Neutron Scattering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Petrenko, V.I.; Gapon, I.V.; Bulavin, L.A.; Vorobiev, A.A.; Soltwedel, O.; Balasoiu, M.; Vékás, L.; Zavisova, V.; Kopcansky, P. Comparative Structure Analysis of Magnetic Fluids at Interface with Silicon by Neutron Reflectometry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 352, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, P.; Wetterskog, E.; Honecker, D.; Fock, J.; Frandsen, C.; Moerland, C.; Bogart, L.K.; Posth, O.; Szczerba, W.; Gavilán, H.; et al. Dipolar-coupled moment correlations in clusters of magnetic nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 224420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscas, G.; Concas, G.; Laureti, S.; Testa, A.M.; Mathieu, R.; De Toro, J.A.; Cannas, C.; Musinu, A.; Novak, M.A.; Sangregorio, C.; et al. The interplay between single particle anisotropy and interparticle interactions in ensembles of magnetic nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 28634–28643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socoliuc, V.; Turcu, R.; Kuncser, V.; Vékás, L. Magnetic Characterization. In Contrast Agents for MRI. Experimental Methods; Pierre, V.C., Allen, M.J., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018; pp. 391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Shasha, C.; Krishnan, K.M. Nonequilibrium Dynamics of Magnetic Nanoparticles with Applications in Biomedicine. Adv. Mater. 2020, 1904131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shliomis, M.I. Ferrohydrodynamics: Retrospective and Issues. In Ferrofluids; Odenbach, S., Ed.; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, W.T.; Kalmykov, Y.P. Thermal fluctuations of magnetic nanoparticles: Fifty years after Brown. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 121301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckhoff, J.; Eberbeck, D.; Schilling, M.; Ludwig, F. Magnetic-field dependence of Brownian and Neel relaxation times. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 043903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensweig, R.E. Ferrohydrodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985; Reprinted with slight modifications by Mineola, New York Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

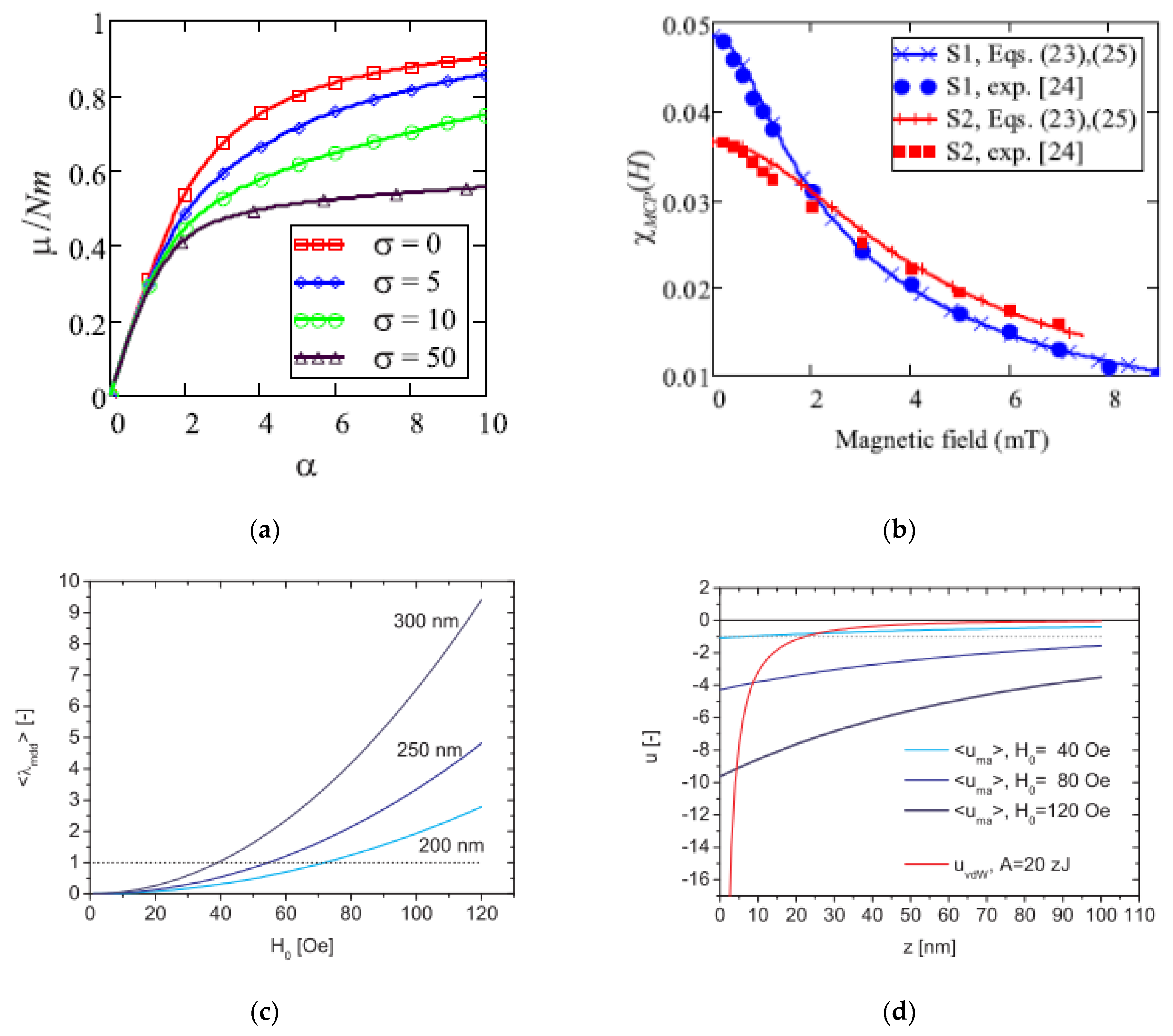

- Ivanov, A.O.; Kantorovich, S.S.; Reznikov, E.N.; Holm, C.; Pshenichnikov, A.F.; Lebedev, A.V.; Chremos, A.; Camp, P.J. Magnetic properties of polydisperse ferrofluids: A critical comparison between experiment, theory, and computer simulation. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 061405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalai, I.; Nagy, S.; Dietrich, S. Linear and nonlinear magnetic properties of ferrofluids. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 92, 042314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, V.; Wahnström, G.; Sanz-Velasco, A.; Gustafsson, S.; Olsson, E.; Enoksson, P.; Johansson, C. Effective magnetic moment of magnetic multicore nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 092406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.O.; Ludwig, F. Static magnetic response of multicore particles. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 032603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socoliuc, V.; Turcu, R. Large scale aggregation in magnetic colloids induced by high frequency magnetic fields. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 500, 166348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.A. Zero-Field and Field-Induced Interactions between Multicore Magnetic Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socoliuc, V.; Vékás, L.; Turcu, R. Magnetically induced phase condensation in an aqueous dispersion of magnetic nanogels. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 3098–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

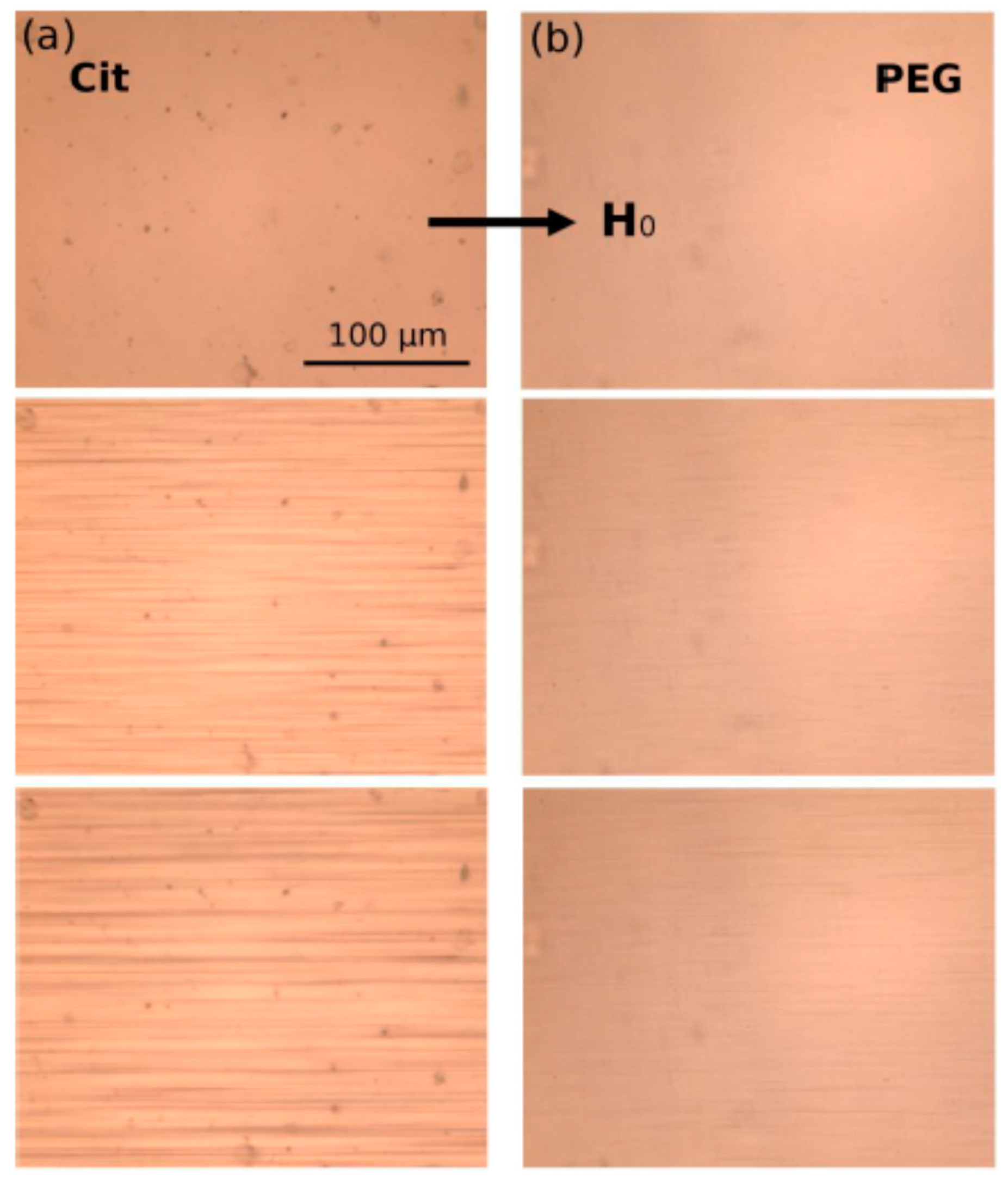

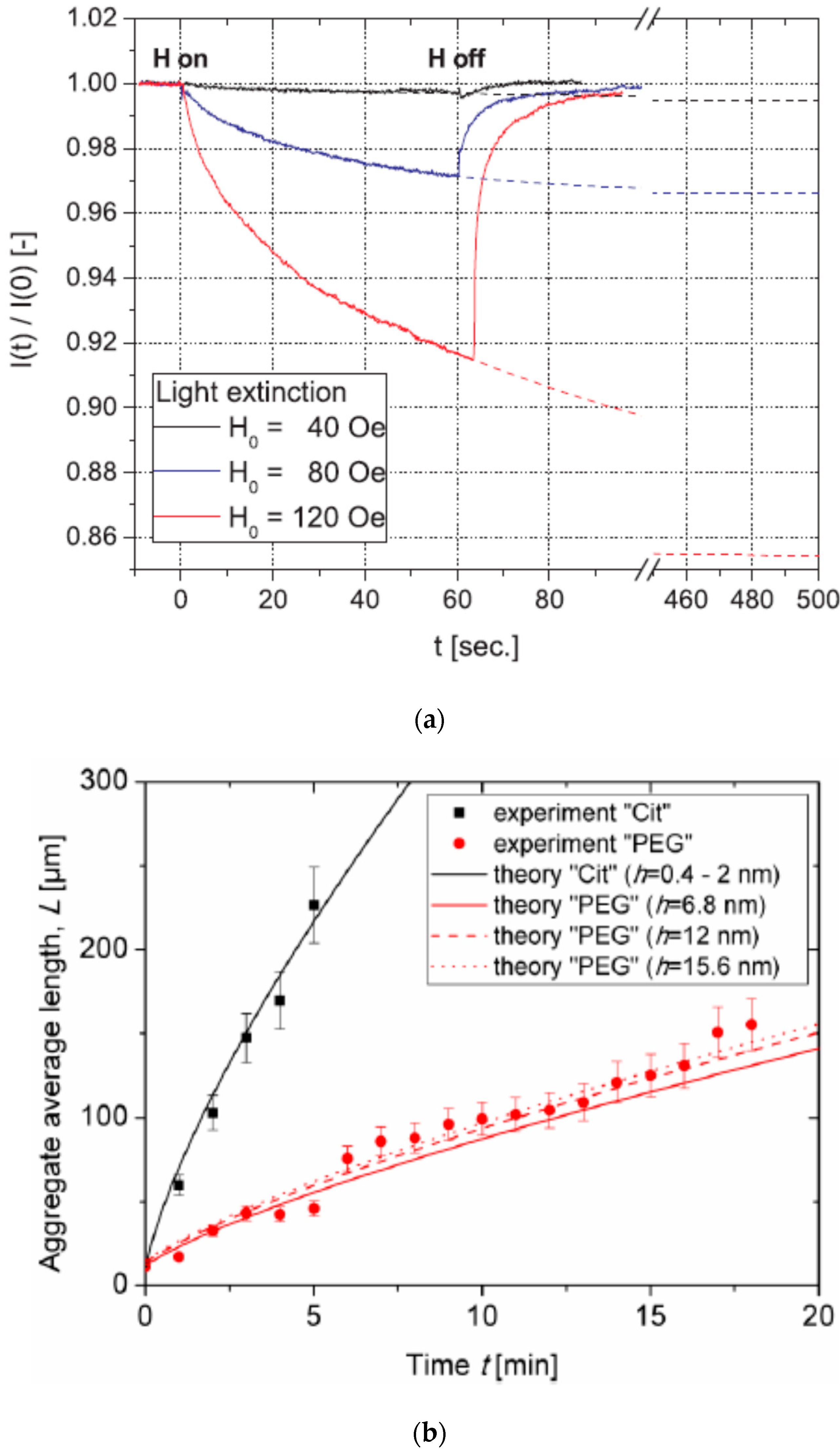

- Ezzaier, H.; Marins, J.A.; Claudet, C.; Hemery, G.; Sandre, O.; Kuzhir, P. Kinetics of Aggregation and Magnetic Separation of Multicore Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Effect of the Grafted Layer Thickness. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, S.L.; Woodward, R.C.; House, M.J.; Tokarev, A.; Hammers, J.; Qi, B.; Shaw, J.; Saunders, M.; Varsani, R.R.; St Pierre, T.G.; et al. The effect of magnetically induced linear aggregates on proton transverse relaxation rates of aqueous suspensions of polymer coated magnetic nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 2152–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.T. Role of dipolar interaction in magnetic hyperthermia. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 014403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasson, C.; Schaller, V.; Zeng, L.; Olsson, E.; Frandsen, C.; Castro, A.; Nilsson, L.; Bogart, L.K.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A.; et al. Modelling the effect of different core sizes and magnetic interactions inside magnetic nanoparticles on hyperthermia performance. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 477, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirou, S.V.; Basini, M.; Lascialfari, A.; Sangregorio, C.; Innocenti, C. Magnetic Hyperthermia and Radiation Therapy: Radiobiological Principles and Current Practice. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, P.; Fock, J.; Hansen, M.F.; Bogart, K.; Southern, P.; Ludwig, F.; Wiekhorst, F.; Szczerba, W.; Zeng, L.J.; Heinke, D. Influence of clustering on the magnetic properties and hyperthermia performance of iron oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 425705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, R.; Stapf, M.; Dutz, S.; Müller, R.; Teichgräber, U.; Hilger, I. Structural properties of magnetic nanoparticles determine their heating behavior—An estimation of the in vivo heating potential. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krasia-Christoforou, T.; Socoliuc, V.; Knudsen, K.D.; Tombácz, E.; Turcu, R.; Vékás, L. From Single-Core Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids to Multi-Core Magnetic Nanocomposites: Assembly Strategies, Structure, and Magnetic Behavior. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10112178

Krasia-Christoforou T, Socoliuc V, Knudsen KD, Tombácz E, Turcu R, Vékás L. From Single-Core Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids to Multi-Core Magnetic Nanocomposites: Assembly Strategies, Structure, and Magnetic Behavior. Nanomaterials. 2020; 10(11):2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10112178

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrasia-Christoforou, Theodora, Vlad Socoliuc, Kenneth D. Knudsen, Etelka Tombácz, Rodica Turcu, and Ladislau Vékás. 2020. "From Single-Core Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids to Multi-Core Magnetic Nanocomposites: Assembly Strategies, Structure, and Magnetic Behavior" Nanomaterials 10, no. 11: 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10112178

APA StyleKrasia-Christoforou, T., Socoliuc, V., Knudsen, K. D., Tombácz, E., Turcu, R., & Vékás, L. (2020). From Single-Core Nanoparticles in Ferrofluids to Multi-Core Magnetic Nanocomposites: Assembly Strategies, Structure, and Magnetic Behavior. Nanomaterials, 10(11), 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10112178