Biochemical Markers Involved in Bone Remodelling During Orthodontic Tooth Movement

Abstract

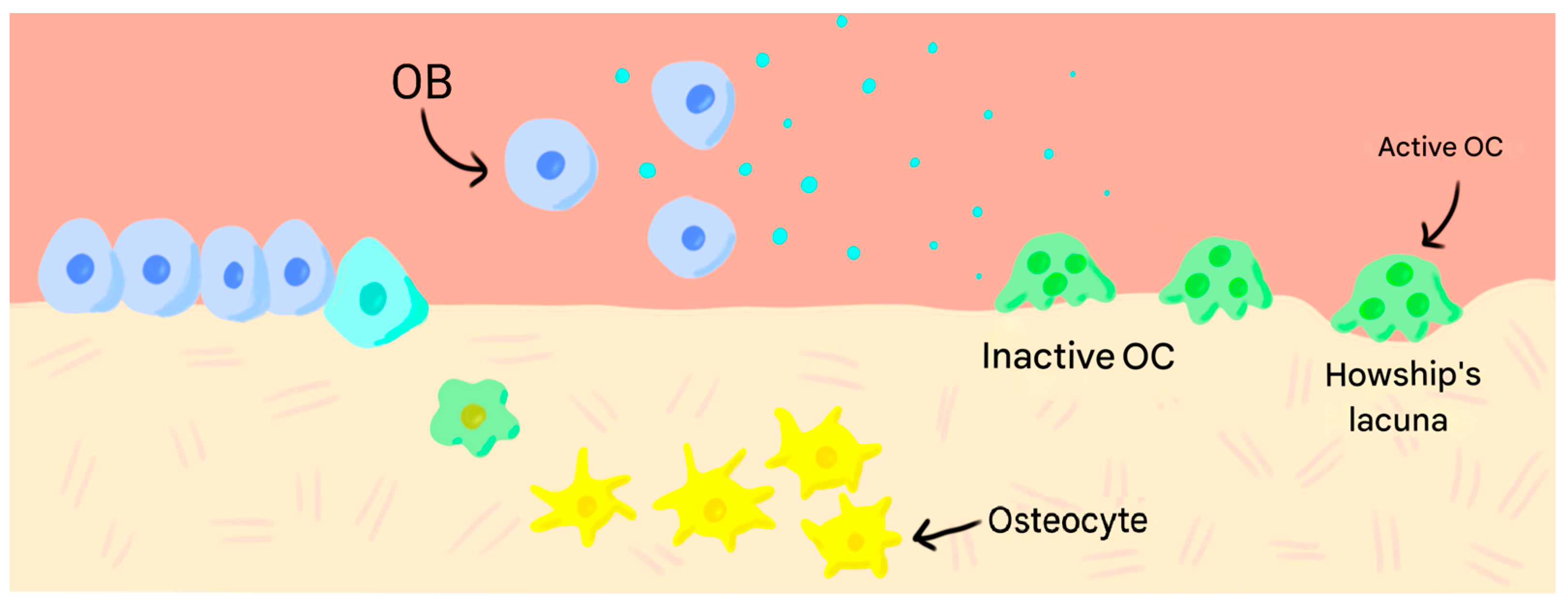

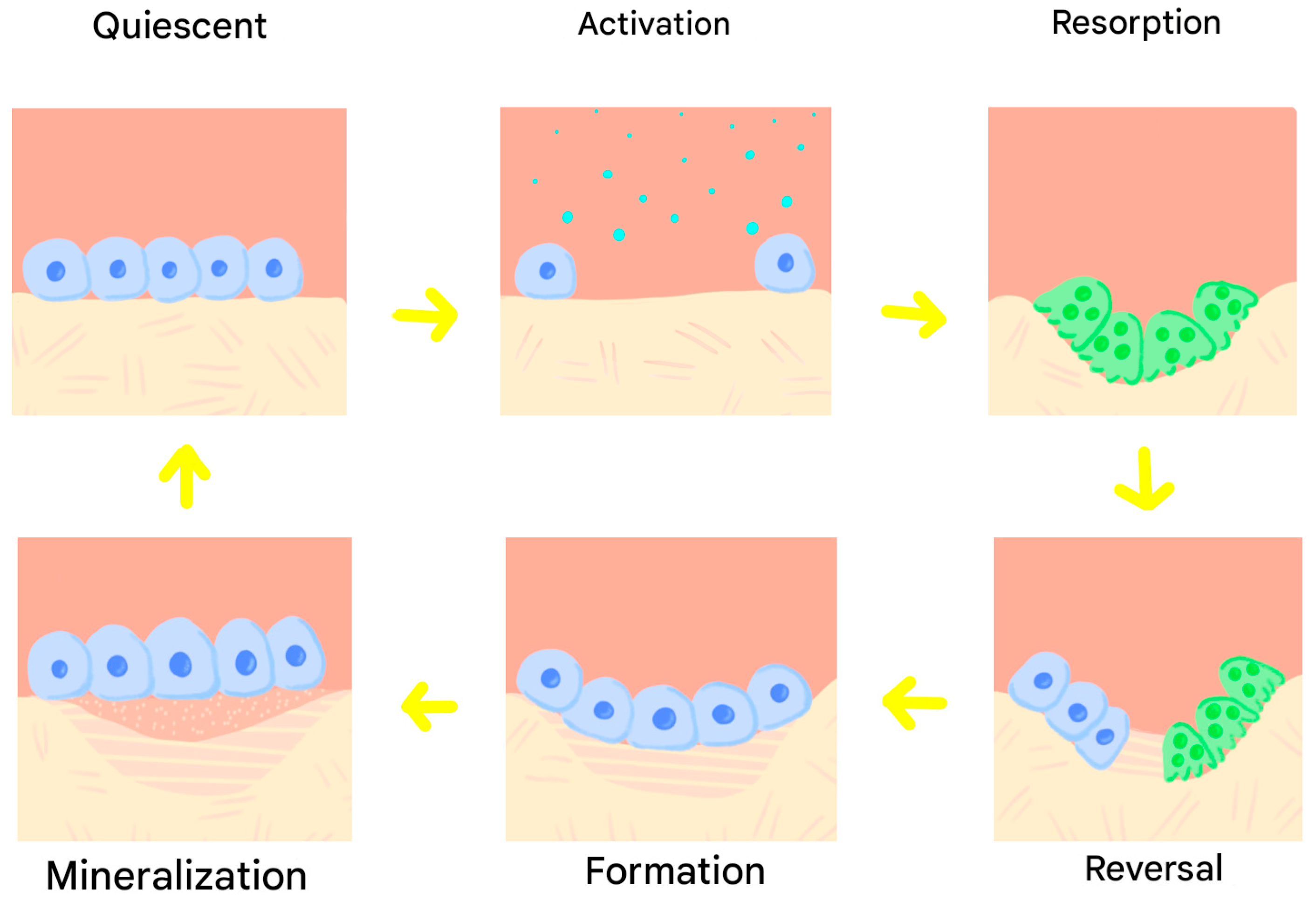

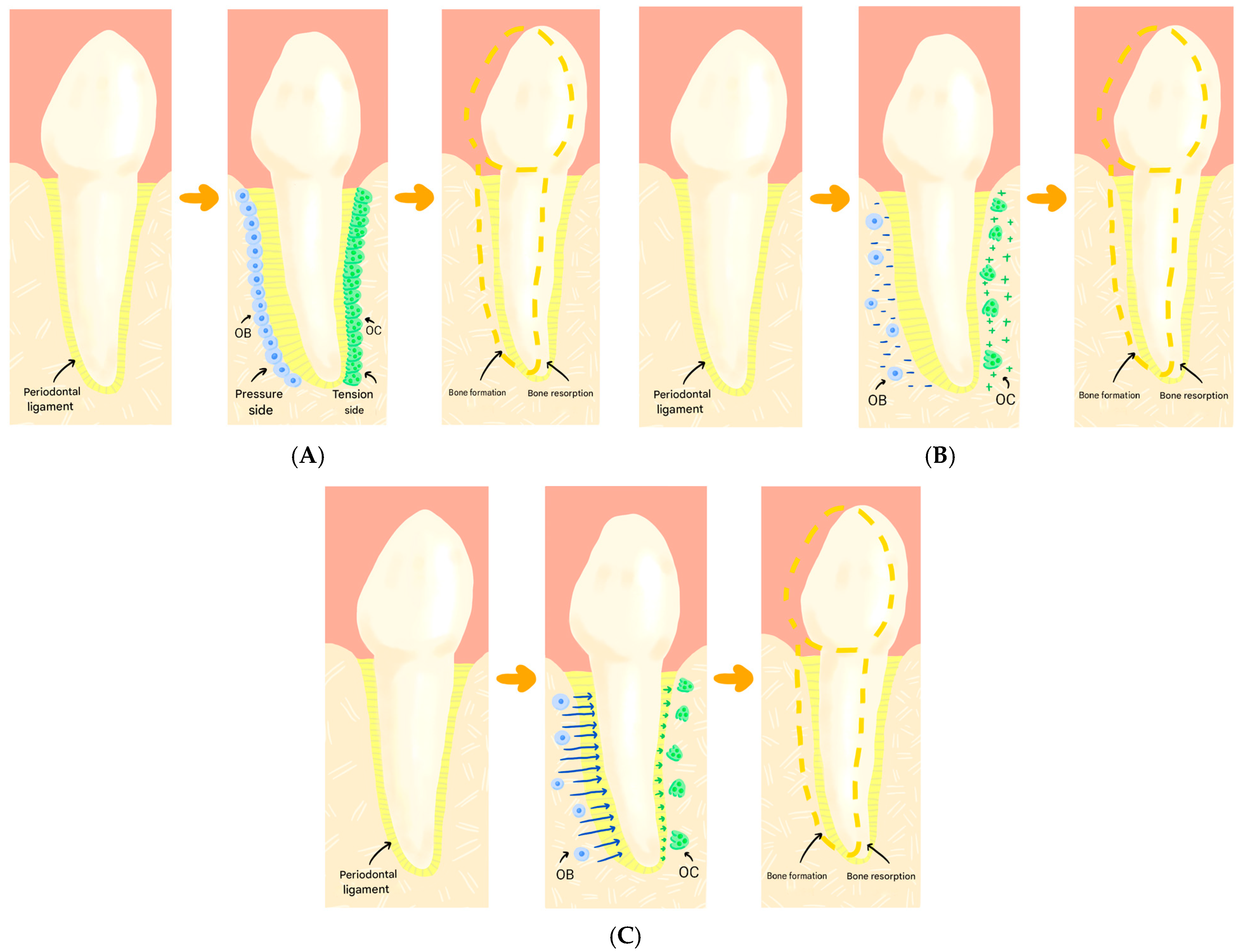

1. Introduction

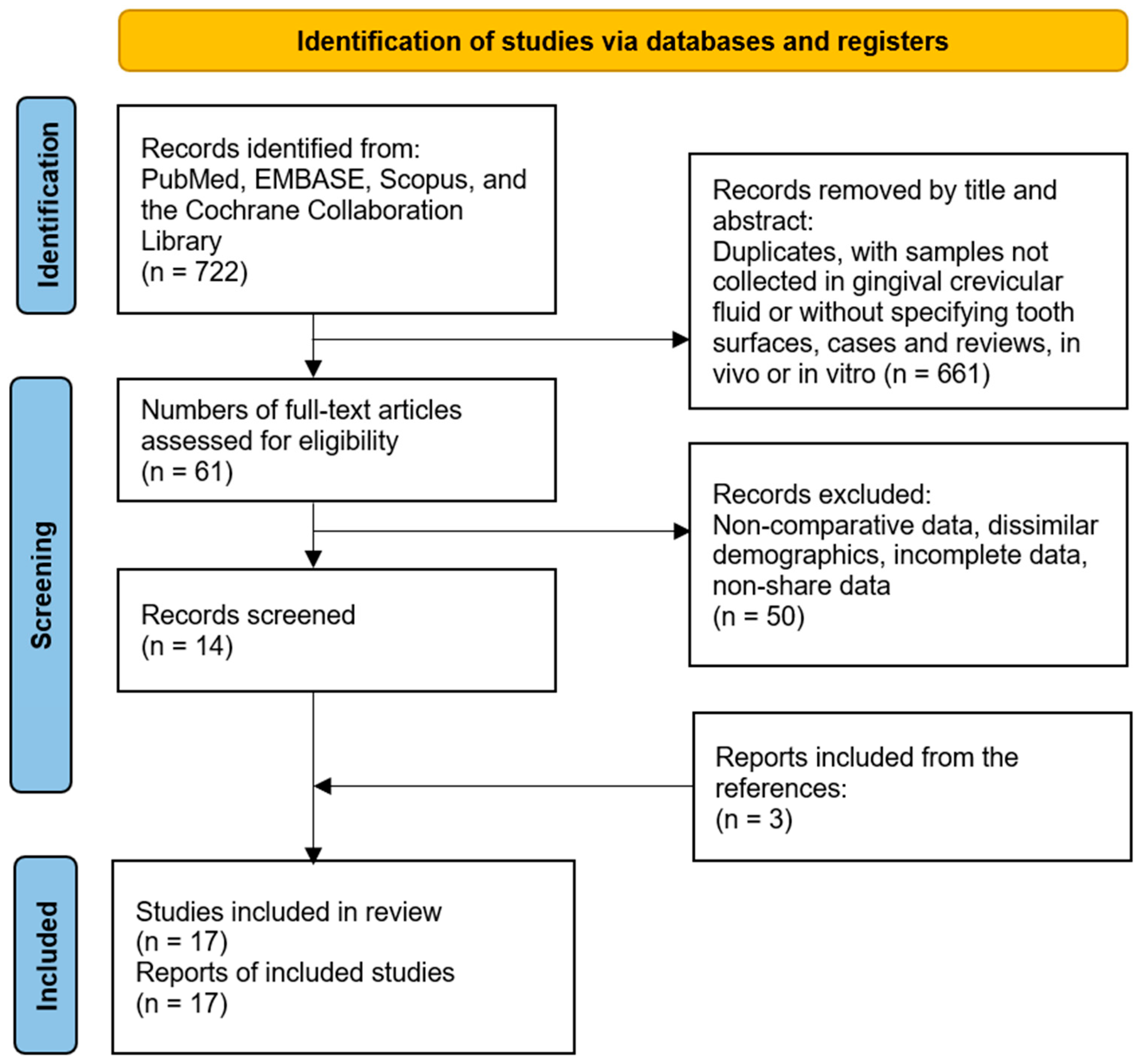

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Bone Formation Markers

3.1.1. Osteoprotegerin (OPG)

3.1.2. Transforming Growth Factor β1 (TGF-β1)

3.1.3. Interleukin 27 (Il-27)

3.1.4. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)

3.1.5. Osteocalcin (OCN)

3.1.6. Type 1 Collagen (COL-1)

3.2. Bone Resorption Markers

3.2.1. Receptor Activator of Factor Nuclear Kappa β Ligand (RANKL)

3.2.2. Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF-α)

3.2.3. Interleukins

3.2.4. Osteopontin (OPN)

3.2.5. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

3.2.6. Receptor Activator of Factor Nuclear Kappa β (RANK)

3.2.7. Calcitonin (CT)

3.2.8. Matrix Metallopeptidases

3.2.9. Substance P (SP)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OB | Osteoblast |

| OC | Osteoclast |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| CT | Calcitonin |

| GCF | Gingival Crevicular Fluid |

| PDL | Periodontal ligament |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor β 1 |

| IL-27 | Interleukin 27 |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa β Ligand |

| TNF-α | Tumour Necrosis Factor-α |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| OPN | Osteopontin |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa β |

| IL-17A | Interleukin 17A |

| IL-17F | Interleukin 17F |

| IL-23 | Interleukin 23 |

| MMP-1 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 1 |

| MMP-9 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 |

| SP | Substance P |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| COL-1 | Collagen Type 1 |

| TIMP-1 | Metallopeptidase Inhibitor 1 |

| TIMP-2 | Metallopeptidase Inhibitor 2 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| TRAP | Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase |

| TRAP5b | Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase 5b |

| IL-1α | Interleukin 1α |

| IL-2 | Interleukin 2 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin 13 |

| IL-16 | Interleukin 16 |

References

- Fernández-Tresguerres Hernández-Gil, I.; Alobera Gracia, M.Á.; Del Canto Pingarrón, M.; Blanco Jerez, L. Bases fisiológicas de la regeneración ósea II: El Proceso remodelado. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2006, 11, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Neyro Bilbao, J.; Cano Sánchez, A.; Palacios Gil-Antuñano, S. Regulación del metabolismo óseo a través del sistema RANK-RANKL-OPG. Rev. Osteoporos. Metab. Min. 2011, 3, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.M.; Lin, C.; Stavre, Z.; Greenblatt, M.B.; Shim, J.H. Osteoblast-Osteoclast Communication and Bone Homeostasis. Cells 2020, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.; Pawlina, W. Histología: Texto y Atlas Color con Biología Celular y Molecular, 5th ed.; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 218–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki, H.; Chiba, M.; Takahashi, I.; Haruyama, N.; Nishimura, M.; Mitani, H. Local OPG gene transfer to periodontal tissue inhibits orthodontic tooth movement. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, D.; Arai, A.; Zhao, L.; Yang, M.; Nakamichi, Y. RANKL/OPG ratio regulates odontoclastogenesis in damaged dental pulp. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Gallego, J.; Manchado-Morales, P.; Pivonka, P.; Martínez-Reina, J. Spatio-temporal simulations of bone remodelling using a bone cell population model based on cell availability. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1060158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.; Partridge, N. Physiological Bone Remodeling: Systemic Regulation and Growth Factor Involvement. Physiology 2016, 31, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, S.; Brady, J. Collagen Cross-Linking and Metabolism. In Principles of Bone Biology, 2nd ed.; Robins, S.P., Brady, J.D., Eds.; Elesevier: Scotland, UK, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Riancho, J.A.; Delgado-Calle, J. Mecanismos de interacción osteoblasto-osteoclasto. Reum. Clin. 2011, 7, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal Ariffin, S.; Yamamoto, Z.; Zainol Abidin, I.; Megat Abdul Wahab, R.; Ariffin, Z. Cellular and molecular changes in orthodontic tooth movement. Sci. World J. 2011, 11, 1788–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueta, J. The role of blood vessels in osteogenesis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1963, 45, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjidakis, D.J.; Androulakis, I.I. Bone Remodeling. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2006, 1092, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Idarraga, A. Medición de RANKL y OPG en Fluido Crevicular Durante el Tratamiento de Ortodoncia Invisalign®, con y sin Fuerzas Intermitentes Mediante Acceledent®; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes García, R.; Rozas Moreno, P.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Regulación del proceso de remodelado óseo. REEMO 2008, 17, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, M.; Moonga, B.; Abe, E. Calcitonin and bone formation: A knockout full of surprises. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1769–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.; Henriksen, K.; Arnold, M.; Christiansen, C. Calcitonin: A drug of the past or for the future? Physiologic inhibition of bone resorption while sustaining osteoclast numbers improves bone quality. BioDrugs 2008, 22, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Saravanan, K.; Kohila, K.; Kumar, S. Biomarkers in orthodontic tooth movement. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, M. The tissue, cellular, and molecular regulation of orthodontic tooth movement: 100 years after Carl Sandstedt. Eur. J. Orthod. 2006, 28, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, N. A treatise on oral deformities as a branch of mechanical surgery. Am. J. Dent. Sci. 1880, 13, 571. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstedt, C. Einige Beiträge zur Theorie der Zahnregulierung. Nord. Tandläkare Tidskr. 1904, 5, 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstedt, C. Einige Beiträge zur Theorie der Zahnregulierung. Nord. Tandläkare Tidskr. 1905, 6, 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A. Tissue changes, particularly of the bone, incident to tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. 1911, 3, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A. Tissue changes incidental to orthodontic tooth movement. Int. J. Orthod. Oral. Surg. Radiogr. 1932, 18, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, E.; Yasuda, I. On the Piezoelectric Effect of Bone. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1957, 12, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brännström. Communication between the oral cavity and the dental pulp associated with restorative treatment. Oper. Dent. 1984, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barbieri Petrelli, G. Cambios Bioquímicos del Metabolismo Óseo Durante el Movimiento Ortodóncico; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/science/biomarkers (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Jaraback, J.; Fizzell, J. Technique and Treatment with Light-Wire Edgewise Appliances, 1st ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, B.; Öztürk, V.Ö.; Geçgelen Cesur, M.; Köse, T.; Bostanci, N. Effect of orthodontic force magnitude on cytokine networks in gingival crevicular fluid: A longitudinal randomized split-mouth study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, J.A.; Linde, D.; Barbieri, G.; Solano, P.; Caba, O.; Rios-Lugo, M.J.; Sanz, M.; Martin, C. Calcitonin gingival crevicular fluid levels and pain discomfort during early orthodontic tooth movement in young patients. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2013, 58, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, M.; Raptis, M.; Zoldan, B.; Sangsuwon, C.; Lee, Y.B.; Alyami, B.; Corpodian, C.; Barrera, L.M.; Alansari, S.; Khoo, E.; et al. Effect of micro-osteoperforations on the rate of tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, G.; Solano, P.; Alarcón, J.A.; Vernal, R.; Rios-Lugo, J.; Sanz, M.; Martín, C. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism in gingival crevicular fluid during early orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castroflorio, T.; Gamerro, E.F.; Caviglia, G.; Deregibus, A. Biochemical markers of bone metabolism during early orthodontic tooth movement with aligners. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudic, A.; Kiliaridis, S.; Mombelli, A.; Giannopoulou, C. Composition changes in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement: Comparisons between tension and compression sides. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2006, 114, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlet, T.P.; Coelho, U.; Silva, J.S.; Garlet, G.P. Cytokine expression pattern in compression and tension sides of the periodontal ligament during orthodontic tooth movement in humans. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2007, 115, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Wilson, J.; Rock, P.; Chapple, I. Induction of cytokines, MMP9, TIMPs, RANKL and OPG during orthodontic tooth movement. Eur. J. Orthod. 2013, 35, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaduman, B.; Uraz, A.; Altan, G.; Tuncer, B.B.; Alkan, Ö.; Gönen, S.; Pehlivan, S.; Çetiner, D. Changes of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-10, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase5b in the crevicular fluid in relation to orthodontic movement. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2015, 13, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Takahashi, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kasai, K. Effects of aging on RANKL and OPG levels in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2006, 9, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Yang, L.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, B. The Changes of Th17 Cytokines Expression and Its Correlation with Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Ligand During Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Ir. J. Inmunol. 2020, 17, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.J.; Park, Y.C.; Yu, H.S.; Choi, S.H.; Yoo, Y.J. Effects of continuous and interrupted orthodontic force on interleukin-1beta and prostaglandin E2 production in gingival crevicular fluid. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 125, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppanapornlarp, S.; Kajii, T.S.; Surarit, R.; Iida, J. Interleukin-1b levels, pain intensity, and tooth movement using two different magnitudes of continuous orthodontic force. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, L.; García Dabeiba, A.; Wilches-Buitrago, L. Expression and Presence of OPG and RANKL mRNA and Protein in Human Periodontal Ligament with Orthodontic Force. Gene Regul. Syst. Biol. 2016, 10, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padisar, P.; Hashemi, R.; Naseh, M.; Nikfarjam, B.; Mohammadi, M. Assessment of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin 6 level in gingival crevicular fluid during orthodontic tooth movement: A randomized split-mouth clinical trial. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 7146–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toygar, H.U.; Kircelli, B.H.; Bulut, S.; Sezgin, N.; Tasdelen, B. Osteoprotegerin in gingival crevicular fluid under long-term continuous orthodontic force application. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, B.B.; Özdemir, B.Ç.; Boynueğri, D.; Karakaya, I.B.; Ergüder, I.; Yücel, A.A.; Aral, L.A.; Özmeriç, N. OPG-RANKL levels after continuous orthodontic force. Gazi Med. J. 2013, 24, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Colburn, W.; DeGruttola, V.; DeMets, D.; Downing, G.; Hoth, D.; Oates, J.A.; Peck, C.C.; Schooley, R.; Spilker, B.; et al. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobral De Aguilar, M.; Perinetti, G.; Capelli, J.J. The Gingival Crevicular Fluid as a Source of Biomarkers to Enhance Efficiency of Orthodontic and Functional Treatment of Growing Patients. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 3257235. [Google Scholar]

- Zavala-Jonguitud, L.F.; Anda, J.C.; Flores-Padilla, M.G.; Pérez, C.; Juárez-Villa, J.D. Correlación entre la insuficiencia o deficiencia de los niveles de vitamina D y las interleucinas 1β y 6. Rev. Alerg. Mex. 2021, 68, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.; Ortiz, M. Marcadores bioquímicos del metabolismo óseo. Rev. Estomat. 2010, 18, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas del Valle, P.; Piñeiro Becerra, M.; Palomino Montenegro, H.; Torres-Quintana, M. Factores modificantes del movimiento dentario ortodóncico. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2010, 26, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Moreno, G.A.; Isaza-Guzmán, D.M.; Tobón-Arroyave, S.I. Time-related changes in salivary levels of the osteotropic factors sRANKL and OPG through orthodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiarena, B.; Kogovsek, N.; Salerni, H.; Castillo, V.; Brandi, G.; Regonat, M.; Visintini, A.; Quintana, H.; Otero, P. Reference values of parathyroid hormone and vitamin D Hormone by chemiluminescent automated assay. RevMVZ Córdoba 2015, 20, 4581–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rody, W.J.; Wijegunasinghe, M.; Wiltshire, W.A.; Dufault, B. Differences in the gingival crevicular fluid composition between adults and adolescents undergoing orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, D.; Liang, M.; Wang, B.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Huo, Y.; et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels and the risk of new-onset diabetes in hypertensive adults. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sells Galvin, R.; Gatlin, C.; Horn, J.; Fuson, T. TGF-beta enhances osteoclast differentiation in hematopoietic cell cultures stimulated with RANKL and M-CSF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 265, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, R.M.A.; Abu Kasim, N.; Senafi, S.; Jemain, A.A.; Abidin, I.Z.Z.; Shahidan, M.; Ariffin, S.H.Z. Enzyme Activity Profiles and ELISA Analysis of Biomarkers from Human Saliva and Gingival Crevicular Fluid during Orthodontic Tooth Movement Using Self-Ligating Brackets. Oral. Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ono, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sasaki, F.; Nakashima, T. RANKL biology: Bone metabolism, the immune system, and beyond. Inflamm. Regen. 2020, 40, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Flores, J.; Villafán-Bernal, J.R.; Rivera-León, E.A.; Llamas-Covarrubias, I.M.; González-Hita, M.E.; Alcalá-Zermeno, J.L.; Alcalá-Zermeno, J.L.; Sánchez-Enríquez, S. Niveles de referencia de osteocalcina en población sana de México. Gac. Med. Mex. 2018, 154, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Hazemeijer, H.; de Haan, B.; Qu, N.; de Vos, P. Cytokine Profiles in Crevicular Fluid During Orthodontic Tooth Movement of Short and Long Durations. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuğ Özcan, S.; Ceylan, I.; Ozcan, E.; Kurt, N.; Dağsuyu, I.; Canakçi, C. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Patients with Fixed Orthodontic Appliances. Dis. Markers. 2014, 2014, 597892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Gujar, A.; Baeshen, H.; Alhazmi, A.; Ghoussoub, M.S.; Raj, A.; Bhandi, S.; Sarode, S.; Awan, K.; Birkhed, D. Comparison of Biochemical Markers of Bone Metabolism Between Conventional Labial and Lingual Fixed Orthodontic Appliances. Niger. J. Clin. Pr. 2020, 23, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, G.H.; Schultz, C.; Trein, M.P.; Mundstock, K.S.; Weidlich, P.; Goularte, J.F. Association among pain, masticatory performance, and proinflammatory cytokines in crevicular fluid during orthodontic treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaine, J.K.; Rabie, A.B.M.; Wong, R. Does orthodontic tooth movement cause an elevation in systemic inflammatory markers? Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, S.; Chouinard, M.C.; Landa, D.F.; Nanda, R.; Chandhoke, T.; Sobue, T.; Allareddy, V.; Kuo, C.-L.; Mu, J.; Uribe, F. Biomarkers of orthodontic tooth movement with fixed appliances and vibration appliance therapy: A pilot study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Clearly Stated Aim | Consecutive Patients | Prospective Collection Data | Endpoints | Assessment Endpoint | Follow-Up Period | Loss Less Than 5% | Study Size | Adequate Control Group | Contemporary Group | Baseline Control | Statistical Analyses | Minors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afacan B, 2019 [32] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Alarcón JA, 2013 [33] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Alikhani M, 2013 [34] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| Barbieri G, 2013 [35] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Castrofolio T, 2017 [36] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Dudic A, 2006 [37] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| Garlet TP, 2007 [38] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 13 |

| Grant M, 2013 [39] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Karaduman B, 2015 [40] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Kawasaki K, 2006 [41] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| Lin T, 2020 [42] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Lee KJ, 2004 [43] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Luppanapornlarp S, 2010 [44] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Otero L, 2016 [45] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Padisar P, 2018 [46] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Toygar HU, 2008 [47] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Tuncer BB, 2013 [48] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Study | Biochemical Markers | Follow-Up | N | Teeth | Intervention | Treatment Methods | Sample Collection | Analysis Methods | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afacan B, 2019 [32] | G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-α., IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-2R, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IL-1, TNF-α. | 0 24 h 28 days | 15 | Maxillary canines. | Following extraction of the maxillary first premolars and placement of two MTs, the upper canines were randomly distalised with a continuous force of 75 or 150 g. | Preadjusted edgewise orthodontic brackets (Gemini; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) with 0.022″ slots and 0.019″ × 0.025″ segmented arches. | Paper strips (PerioPaper; OraFlow Inc., Plainview, NY, USA). | Luminex. | In the first 24 h, IL-8 and MCP-1 levels were lower on the pressure sides that received more force. At 28 days, TNF-α and IL-1RA levels increased on both sides. |

| Alarcón JA, 2013 [33] | CT. | 0 1 h 24 h 7 days 15 days | 15 | First upper premolars. | Brackets were placed on the upper central incisors, and an orthodontic force of 100 g was applied using a pre-stretched elastic chain to close the diastema. No archwire was used. | Brackets (0.022–0.028 in. Mini Master, American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, WI, USA) and elastomeric chain (Memory chain, American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, WI, USA). | Periopaper strips (Harco, Tustin, CA, USA). | Western Blot. | CT levels increased significantly at the compression site, especially between 1 h and 7 days later. |

| Alikhani M, 2013 [34] | CCL-2 (MCP1), CCL-3, CCL-5 (RANTES), IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α. | 0 1 day 7 days 28 days | 20 | Maxillary canines. | Following extraction of the first premolars, the canines were retracted using calibrated 100 g NiTi closing-coil springs connected from a temporary anchorage device to a power arm on the canine bracket. | Preadjusted edgewise orthodontic brackets (Gemini; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) with 0.022-inch slots and segmented 0.019 × 0.025-inch stainless steel arch wires. | Filter-paper strips (Oraflow, Smithtown, NY, USA). | Glass slide-based protein array. | IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 increased by 4.6, 2.4, 2.3, and 1.9, respectively, in the control group (compression side), and by 8.6, 8.0, 4.3, and 2.9, respectively, in the experimental group. |

| Barbieri G, 2013 [35] | RANK, OPG, OPN, TGF-β1. | 0 24 h 7 days | 10 | First molars. | An orthodontic elastic separator was placed on the mesial side of the molars. | Orthodontic elastics. | Paper strips (Harco, Tustin, CA, USA). | ELISA. | Both increased expression of bone resorptive mediators (RANK and TGF-β1) and decreased expression of a bone-forming mediator (OPG) on the compression side were detected. |

| Castrofolio T, 2017 [36] | IL-1β, RANKL, OPG, OPN, TGF-β1. | 0 1 h 7 days 21 days | 10 | Second upper molars. | Distalisation of upper second molars by 0.25 mm using invisible orthodontics. | Invisalign® (Align Technology, San Jose, CA, USA) orthodontic appliance. | Paper strips (Oraflow Inc., Plainview, NY, USA). | ELISA. | An increased concentration of bone modelling and remodelling mediators at the presure (IL-1β, RANKL) and tension sites (TGF-16, OPN) was observed. |

| Dudic A, 2006 [37] | IL-1β, SP, PGE2. | −7 days 0 1 min 1 h 1 day 7 days | 18 | First upper or lower molars. | Orthodontic elastic separators were inserted in the mesial area of the upper or lower first molars. | Orthodontic elastic separators. | Durapore filter membranes (pore size: 0.22 μm; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). | ELISA. | The mean IL-1β, SP, and PGE2 values were significantly higher in the E-M sites compared with the C-M sites, on all occasions. |

| Garlet TP, 2007 [38] | COL-I, TIMP-1, TNF-α, RANKL, MMP-1, IL-10, OPG, OCN, TGF-ß. | 7 days | 7 | Upper first premolars. | Teeth were exposed to orthodontic forces (7 N). | The rapid maxillary expansion procedure was performed with Hyrax appliances (Dentaurum, Germany). | NR | qPCR. | The compression side exhibited higher expression of TNF-α, RANKL, and MMP-1, whereas the tension side presented higher expression of IL-10, TIMP-1, COL-I, OPG, and OCN. |

| Grant M, 2013 [39] | MMP9, TIMPs., RANKL, OPG. | 0 4 h 7 days 42 days | 20 | GE: Maxillary canines. GC: Maxillary second molars. | After extraction of the upper first premolars, the canines were distalised using brackets with a force of 100 g. | MBT brackets (3M Unitek, Berkshire, UK), with the following archwire sequence: 0.014″ Ni-Ti → 0.018″ Ni-Ti → 0.018” stainless steel. | Paper strips (Periopaper™ strips (Oraflow Inc., Smithtown, NY, USA)). | Luminex. | Tension sites showed significant increases in IL-1β, IL-8, TNFα, MMP-9 and TIMPs 1 and 2 across all time points, while compression sites exhibited increases in IL-1β and IL-8 after 4 h, MMP-9 after 7 and 42 days and RANKL after 42 days. |

| Karaduman B, 2015 [40] | TNF-α, IL-10, TRAP. | 0 1 h 24 h 7 days 28 days | 9 | Canines. | After extraction of the upper first premolars, the upper canines were distalised using brackets with a continuous force of 150 g. | Orthodontic brackets (Omni Roth, GAC International, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA) with 0.016 × 0.022” Sentalloy segmented arches. | Paper strips (Periopaper-ProFlow Inc., Amityville, Nueva York). | ELISA. | TNF-aα and TRAP5b levels in distal and mesial sites of the test teeth were significantly higher than that at both sites of the controls. The IL-10 concentration decreased during experimental period at both sites of the control and test teeth. |

| Kawasaki K, 2006 [41] | RANKL, OPG. | 0 1 h 24 h 168 h | 30 | Maxillary canines. | After extraction of the first upper premolars, the canines were distalised using brackets with an initial force of 250 g. | Edgewise brackets with 0.018 × 0.025″ slot (Tomy International Inc., Tokyo, Japan). | Paper strips (Periopaper; Harco, Tustin, California). | ELISA. | After 24 h RANKL levels were increased and those of OPG decreased from the compression side. |

| Lin T, 2020 [42] | IL-17, IL-23, IL-27, RANKL. | 0 1 h 24 h 1 week 4 weeks 12 weeks | 30 | Maxillary canines. | After extraction of the first maxillary premolar, the maxillary canines were distalised using fixed orthodontic treatment with a force of 150 g. | NR | Paper strips (Periopaper, Interstate Drug Exchange, Amityville, NY, USA). | ELISA. | IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-23 and RANKL increased significantly in the first week. IL-27 decreased significantly in this period. IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-23 were positively correlated with RANKL. IL-27 was negatively correlated with RANKL. |

| Lee KJ, 2004 [43] | IL-1β, PGE2. | 0 1 h 24 h 1 week 1 week and 1 h 2 weeks 2 weeks and 1 h 2 weeks aand 24 h 3 weeks | 10 | Maxillary canines. | After extraction of the first maxillary premolars, the canines were distalised using continuous force and weekly interrupted force. | Ni-Ti spring calibrated to 100 g and retractor with expansion screw, reactivated weekly. | Paper strips (Periopaper; Proflow, Amityville, NY). | ELISA. | Both types of force (continuous and intermittent) caused a significant increase in IL-1β and PGE2 at 24 h. |

| Luppanapornlarp S, 2010 [44] | Il-1β. | 0 1 h 24 h 1 week 1 month 2 months | 16 | Maxillary canines. | After extraction of the first premolars, the upper canines were distalised by applying a continuous force of 50 g or 150 g. | 0.022-inch slot brackets (Ormco Corp., Brea, CA, USA) and 0.018 × 0.025-inch segmented stainless steel wire arches. | Paper strips (Periopaper; Proflow™ Incorporated, Amityville, Nueva York). | ELISA. | IL-1ß concentration in the 150 g group showed the highest level in the compress side at 24 h and 2 months with significant differences compared with the control group. |

| Otero L, 2016 [45] | RANKL, OPG. | 7 days | 32 | Upper first premolars. | Fixed orthodontic treatment using brackets on the upper first premolar loaded with a force of 4 oz (113 g) or 7 oz (198 g). After this, the tooth was extracted. | Edgewise brackets. | Curette (Hu-Friedy). | ELISA. | RANKL protein level was significantly greater in the pressure sides with 7 oz. Changes in RANKL/OPG protein ratio in experimental and control groups showed a statistically significant difference. OPG did not show statistically significant association with any group. |

| Padisar P, 2018 [46] | TNF-α, IL-6. | 0 1 h 28 days | 10 | Maxillary canines. | After extraction of the first premolars, the upper canines were distalised using brackets and a force of 150 g. | 0.022-inch edgewise brackets and a 0.017 × 0.025-inch arch. | Paper strips (Oraflow, Nueva York). | ELISA. | The level of IL-6 and TNFα at both sides of study teeth was higher than both sides of control teeth at 1 h but the difference was not statistically significant. |

| Toygar HU, 2008 [47] | OPG. | 0 1 h 24 h 168 h 1 month 3 months | 12 | Canines. | After extraction of the first premolars, the canines were distalised using brackets and a continuous force of 150 g. | Vertical slot brackets (GAC International Inc., Bohemia, NY) together with a 0.016 × 0.022” segmented stainless steel archwire. | Paper strips (Periopaper, Harco, Tustin, California). | ELISA. | OPG concentrations in compression sites of the test teeth were decreased in a time-dependent manner compared with the baseline measurements. |

| Tuncer BB, 2013 [48] | OPG, RANKL | 0 1 h 24 h 168 h 1 month | 9 | Maxillary canines. | Distalisation forces were applied generating a continuous force of 200 g. | Orthodontic brackets with segmental 0.016 × 0.022”, stainless-steel archwires and sentalloy closed coil springs. | Paper strips (Periopaper-ProFlow Inc.) | ELISA. | OPG concentration showed an increase on the tension side, while there was a decrease on the compression side at 1 h. RANKL expression did not show significant changes. |

| Biochemical Marker | Baseline Value | Pressure Side | Tension Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPG | 68.22 ± 24.6 | Increases from 1 h to 24 h and decreases at 7 days. | Decreases after 1 h with partial recovery at 24 h and return to baseline at 21 days. |

| TFG-β1 | 173.43 ± 155 | Increases from 6 to 24 h, peaking at 7 days. | Decreases slightly after 24 h and remains stable at 7 days. |

| IL-27 | 0.338 ± 0.069 | Increases from baseline to the first hour, decreasing from 24 h to 4 weeks, with a return to baseline at 12 weeks. | Increases from baseline at 1 h, decreasing from 24 h to 4 weeks, with a return to baseline at 12 weeks. |

| IL-10 | 0.29 ± 0.76 1 | Increases from baseline, remaining steady until 7 days. | No significant changes. |

| OCN | 0.16 ± 0.94 1 | Increases from baseline, remaining steady until 7 days. | Increases slightly at 7 days. |

| COL-1 | 1.7 ± 1.1 1 | Increases from baseline, remaining steady until 7 days. | Increases slightly at 7 days. |

| Biochemical Marker | Baseline Value | Pressure Side | Tension Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| RANKL | 0.0012 ± 0.0004 | Increases after 1 h, peaking after 7 days, and then decreases to 12 weeks. | Decreases at 1 h to 7–21 days. |

| TNF-α | 3.62 ± 3.63 | Increases after 4 h, peaking after 24–72 h, remaining steady until 7 days, and then decreasing after 14–28 days. | Increases slightly at 1 h, returning to baseline at 28 days. |

| IL-1β | 36.4 ± 13.2 | Increases from 4 h to 7 days, at which point it begins to decrease. | Increases slightly at 24 h and decreases at 7 days. |

| IL-6 | 2.56 ± 1.84 | Increases from 4 h with a peak at 24 h, sustained until 7 days and returning to baseline at 28 days. | Increases slightly at 1–4 h, returning to baseline at 28 days. |

| IL-17A | 24.75 ± 7.65 | Increases from 24 h and remains stable at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. | Increases from 24 h and remains at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. |

| IL-17F | 0.0486 ± 0.0163 | Increases from 24 h and remains stable at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. | Increases from 24 h and remains stable at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. |

| 1L-23 | 0.062 ± 0.025 | Increases from 24 h and remains stable at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. | Increases from 24 h and remains stable at 4 weeks, returning to baseline at 12 weeks. |

| OPN | 30.73 ± 72.82 | No significant changes. | Increases with peak at 3 weeks. |

| PGE2 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | Increases at 24 h and begins to decrease at 7 days. | Increases slightly at 24 h and begins to decrease at 7 days. |

| RANK | 8.62 ± 15.27 | Increases at 24 h, decreasing at 7 days. | Increases at 24 h, decreasing at 7 days. |

| CT | 25.9 ± 25.9 | Increases between 1 h and 7 days, remaining stable at 15 days. | No significant changes. |

| MMP-1 | 202.08 ± 132.63 | Increases at 7 days. | Decreases at 7 days. |

| MMP-9 | 23,400.22 ± 22,986.03 | Increase from 4 h to 7 days. | Increase from 4 h to 7 days. |

| SP | 2.2 ± 0.9 | Increases significantly at 24 h, decreases at 7 days. | Slight increase at 24 h and decrease at 7 days. |

| Phase | Bone Formation | Bone Resorption |

|---|---|---|

| Early | IL-27 | NR |

| Acute | OPG TFG-β1 IL-10 OCN COL-1 | RANKL TNF-α IL-1β IL-6 IL-17A IL-17F IL-23 PGE2 RANK SP |

| Late | NR | IL-17A IL-17F IL-23 OPN CT MMP-1 MMP-9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fuentes Vera, B.P.; Dib Zaitun, I.; Pérez de la Cruz, M.Á. Biochemical Markers Involved in Bone Remodelling During Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010007

Fuentes Vera BP, Dib Zaitun I, Pérez de la Cruz MÁ. Biochemical Markers Involved in Bone Remodelling During Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes Vera, Beatriz Patricia, Ibrahim Dib Zaitun, and María Ángeles Pérez de la Cruz. 2026. "Biochemical Markers Involved in Bone Remodelling During Orthodontic Tooth Movement" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010007

APA StyleFuentes Vera, B. P., Dib Zaitun, I., & Pérez de la Cruz, M. Á. (2026). Biochemical Markers Involved in Bone Remodelling During Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010007