Multilayer Ti–Cu Oxide Coatings on Ti6Al4V: Balancing Antibacterial Activity, Mechanical Strength, Corrosion Resistance, and Cytocompatibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Samples’ Characterisation

2.3. Biological Examinations

2.3.1. Cell Culture

2.3.2. Cell Attachment Assay

2.3.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.3.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.3.5. Alizarin Red S Staining

2.3.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.3.7. Antibacterial Evaluation

2.3.8. Biofilm Formation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterisation

3.2. Mechanical Characteristics of the Coated Systems

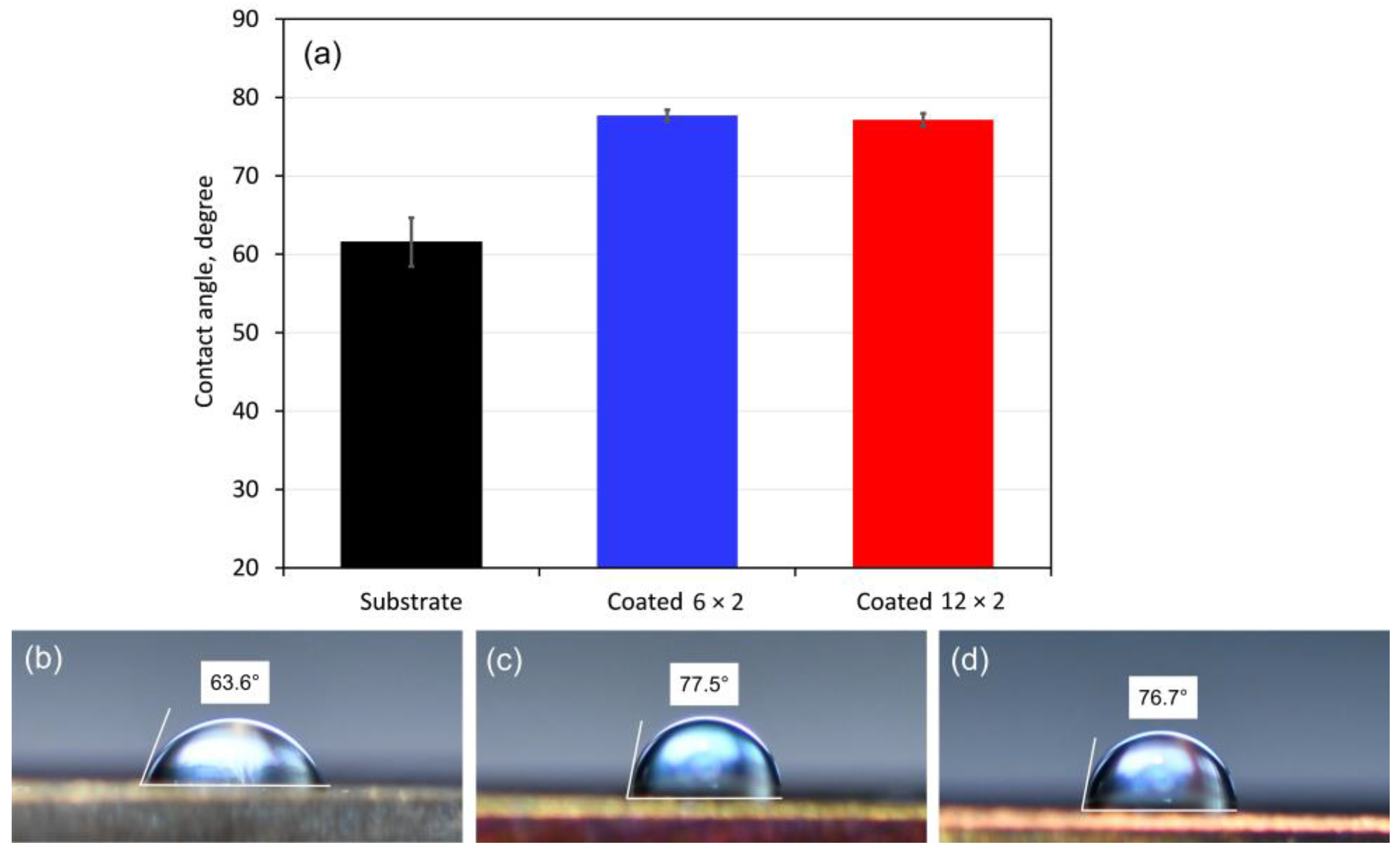

3.3. Wettability

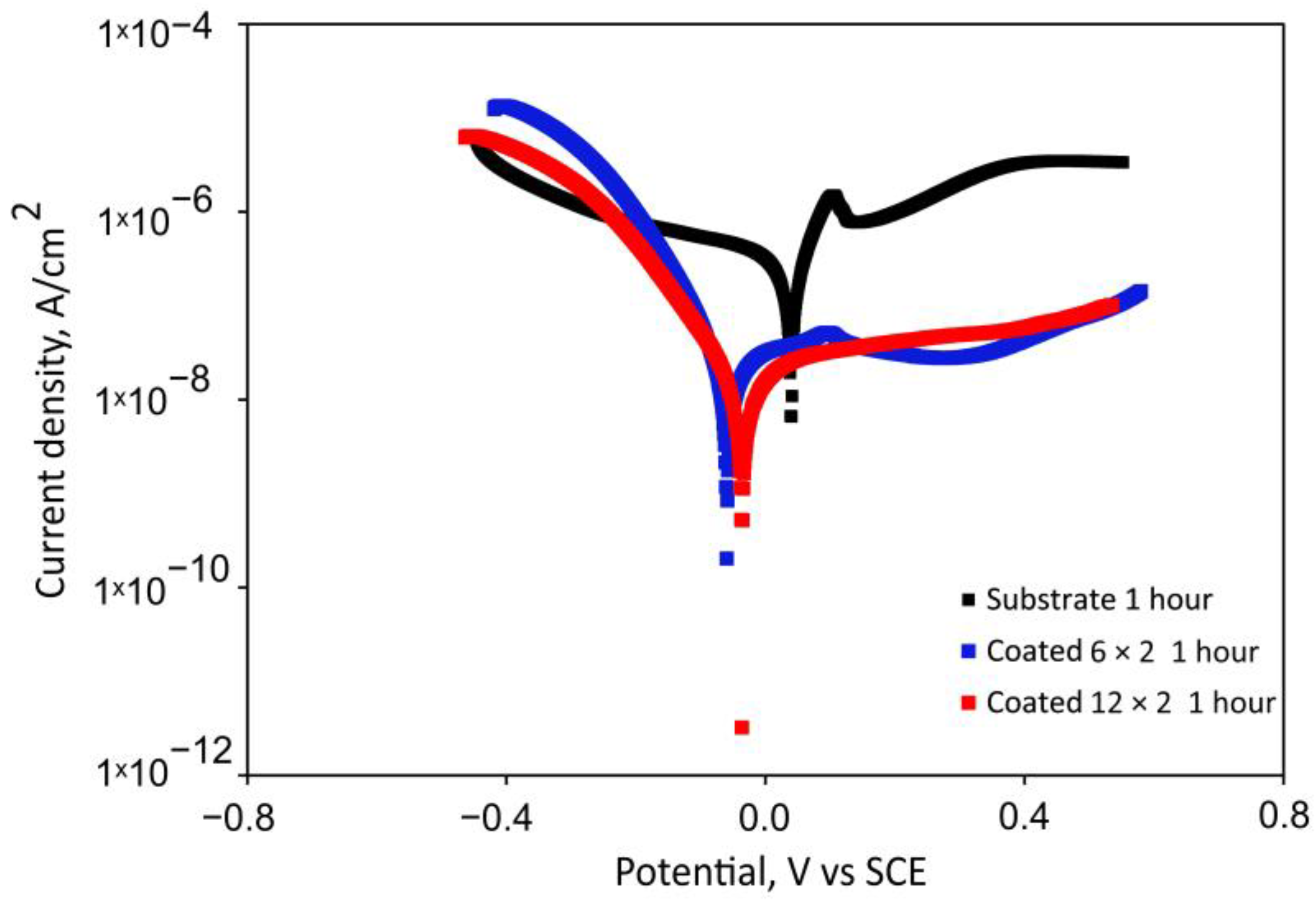

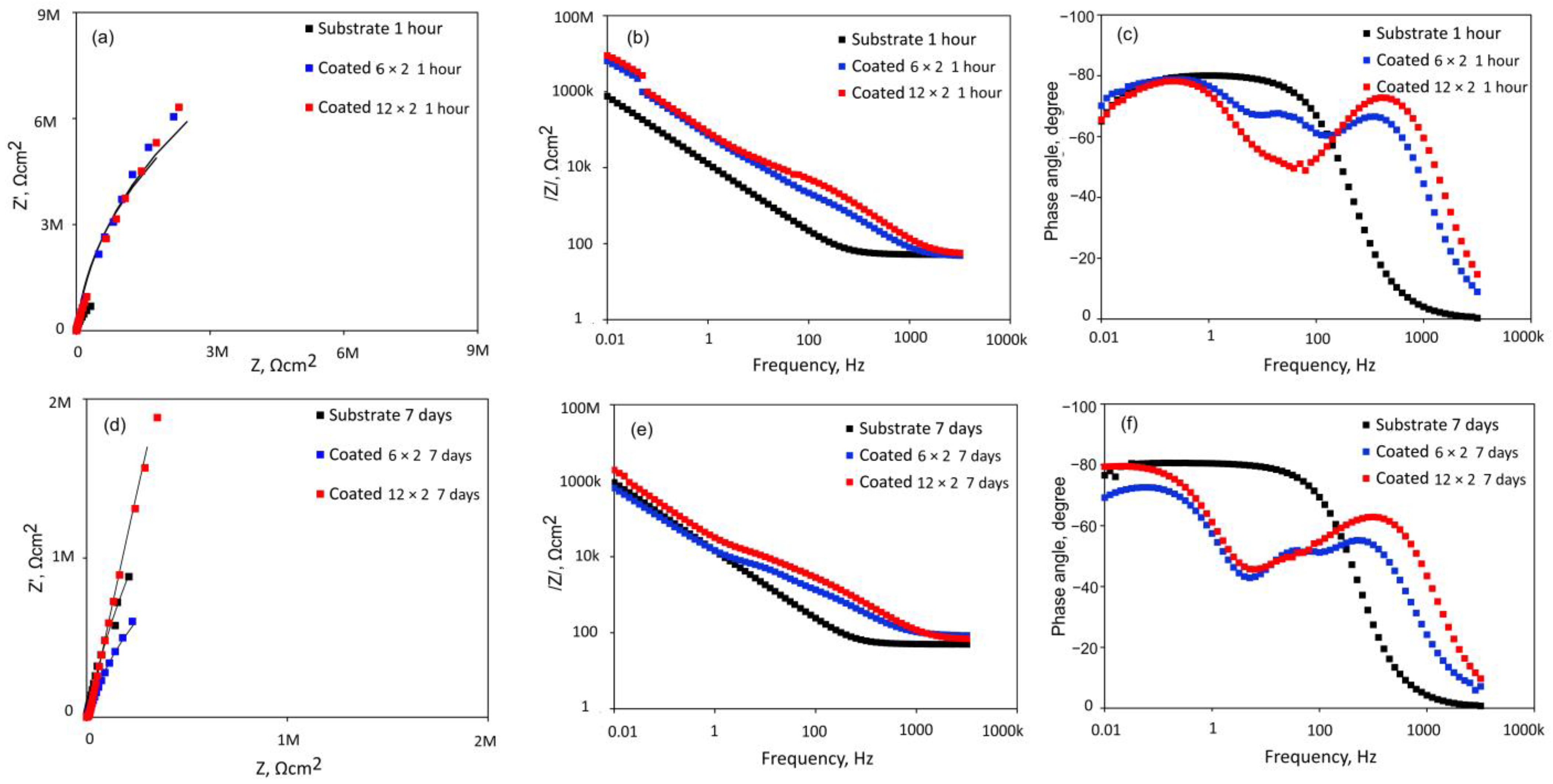

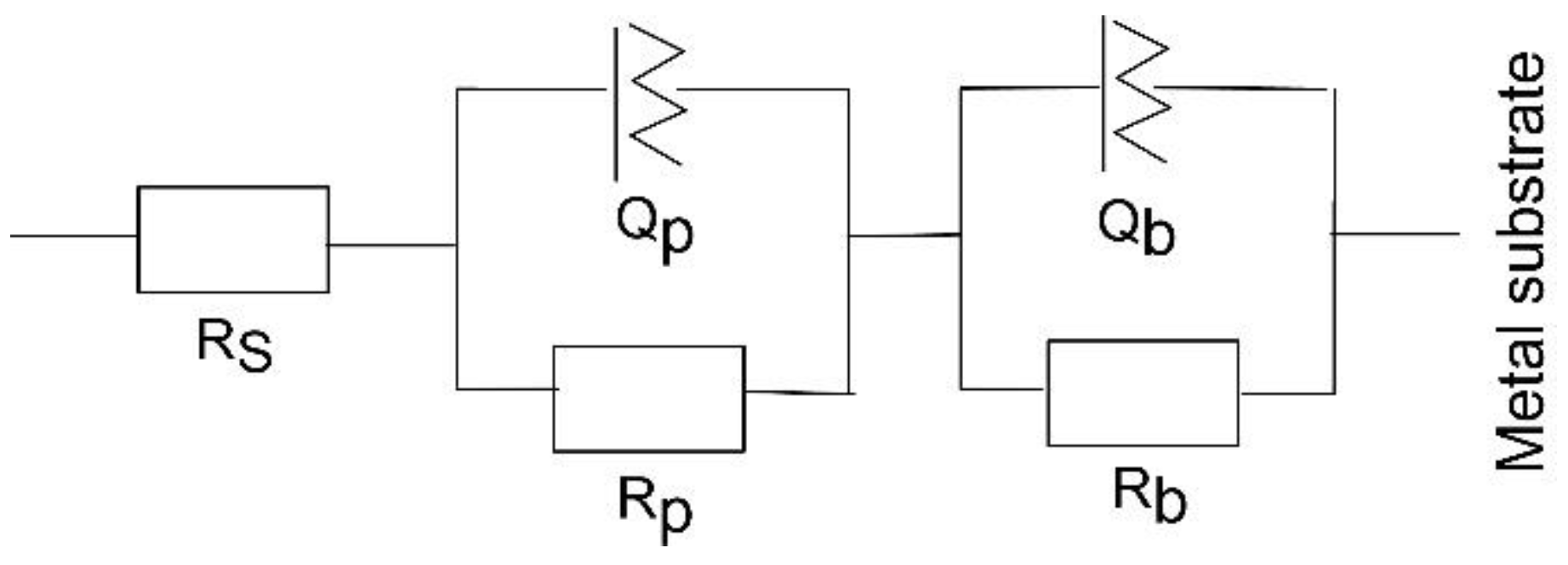

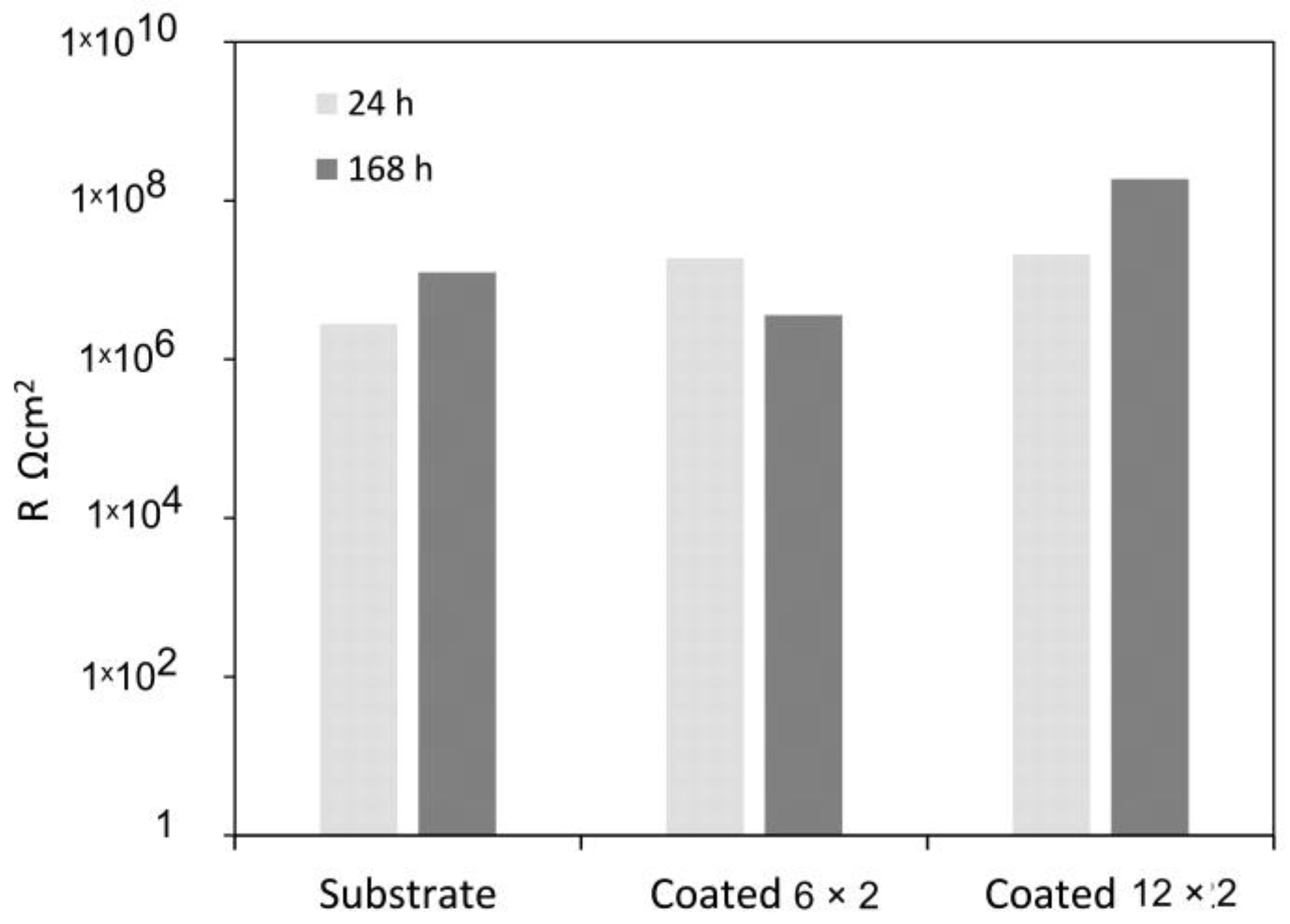

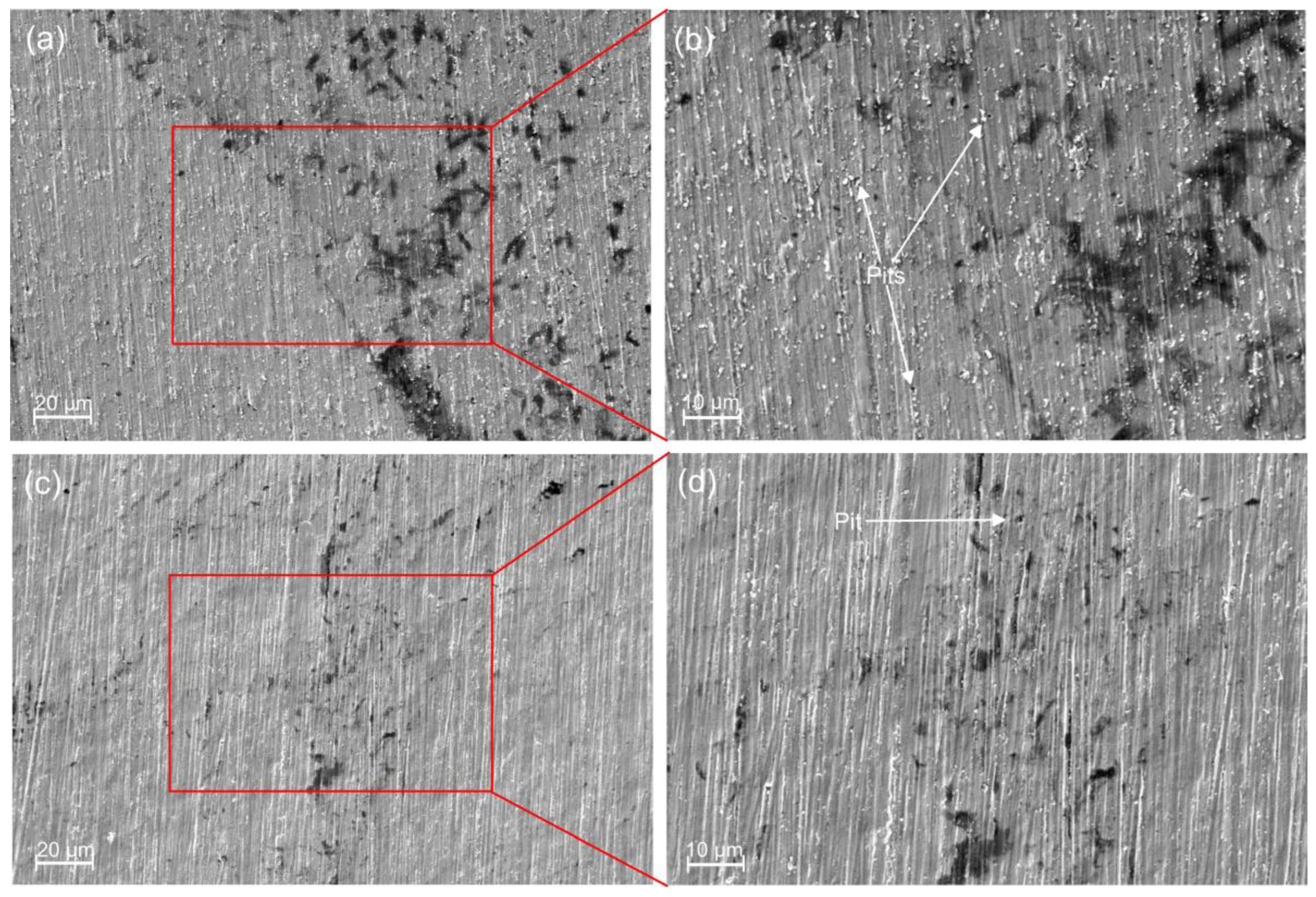

3.4. Electrochemical Tests

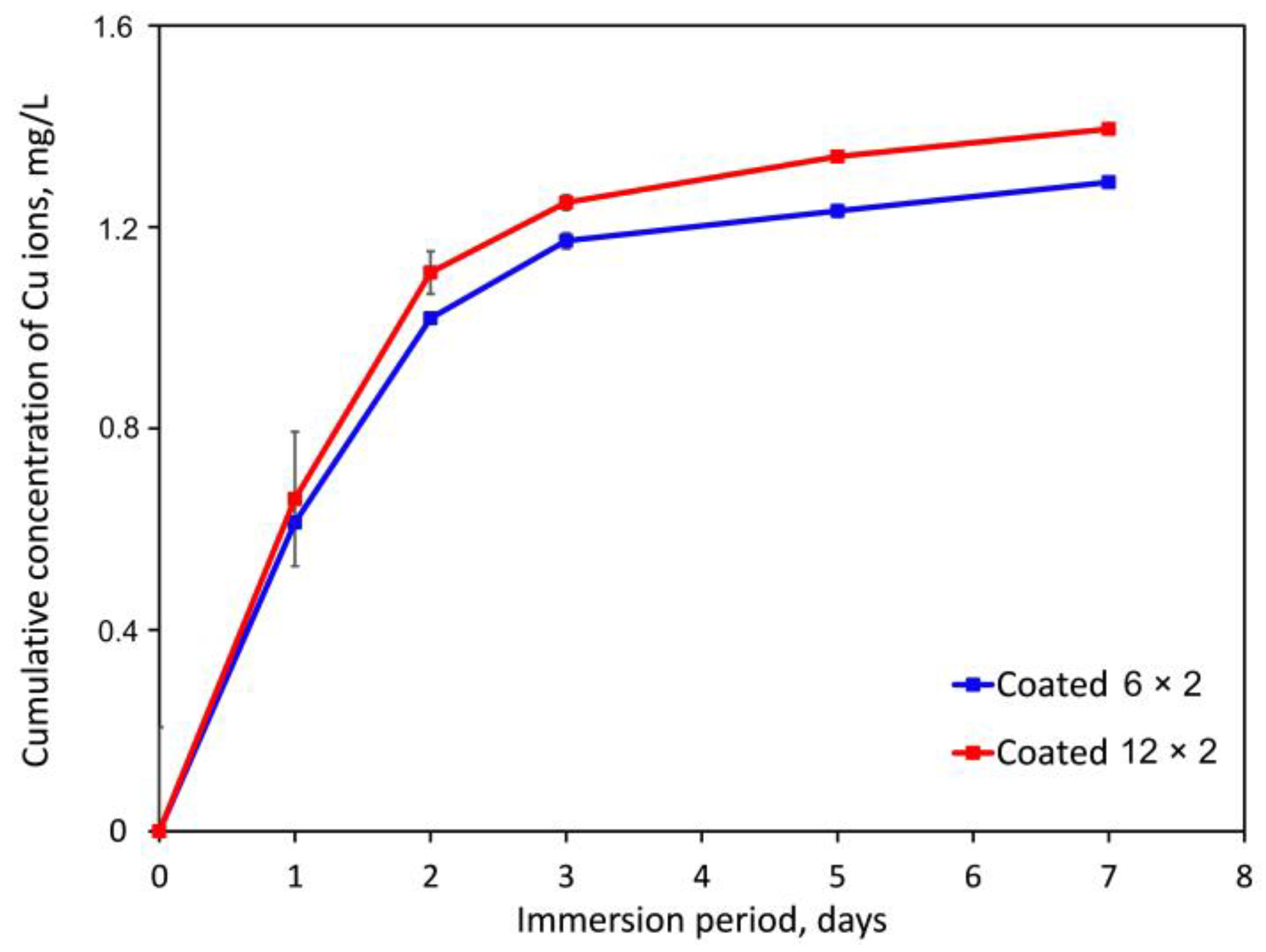

3.5. Copper Ion Release

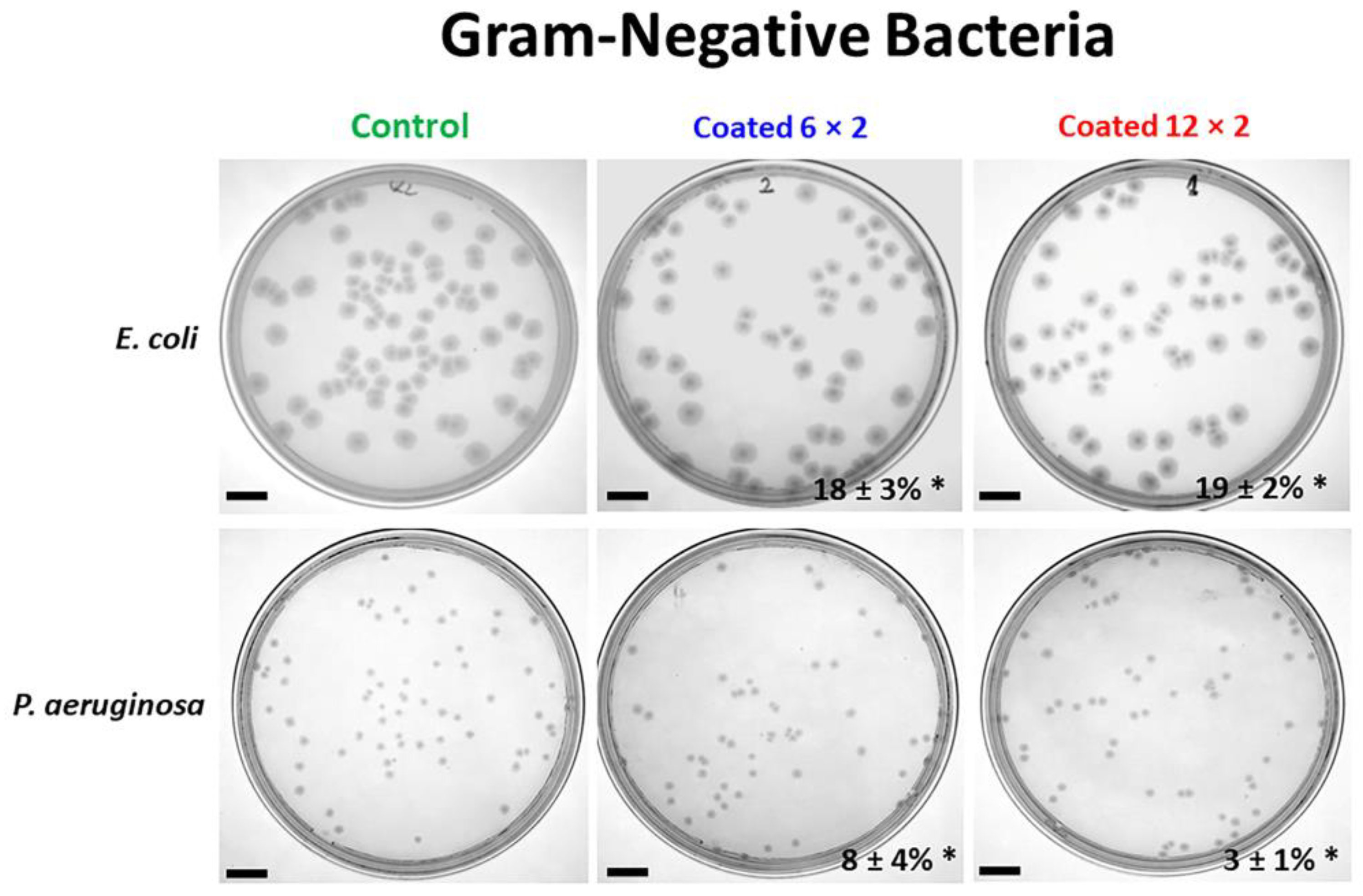

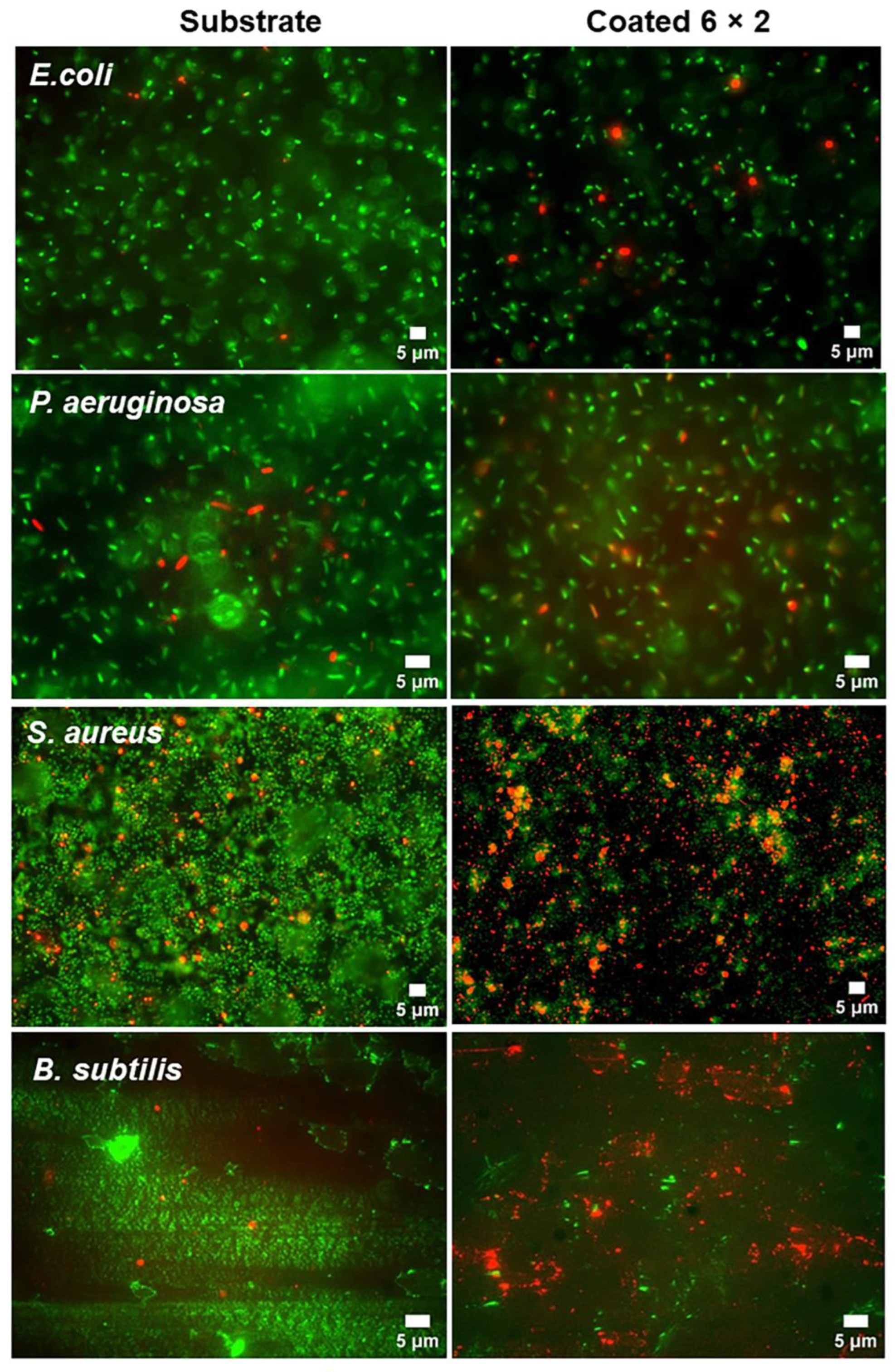

3.6. Antibacterial Properties

3.7. Biofilm Formation

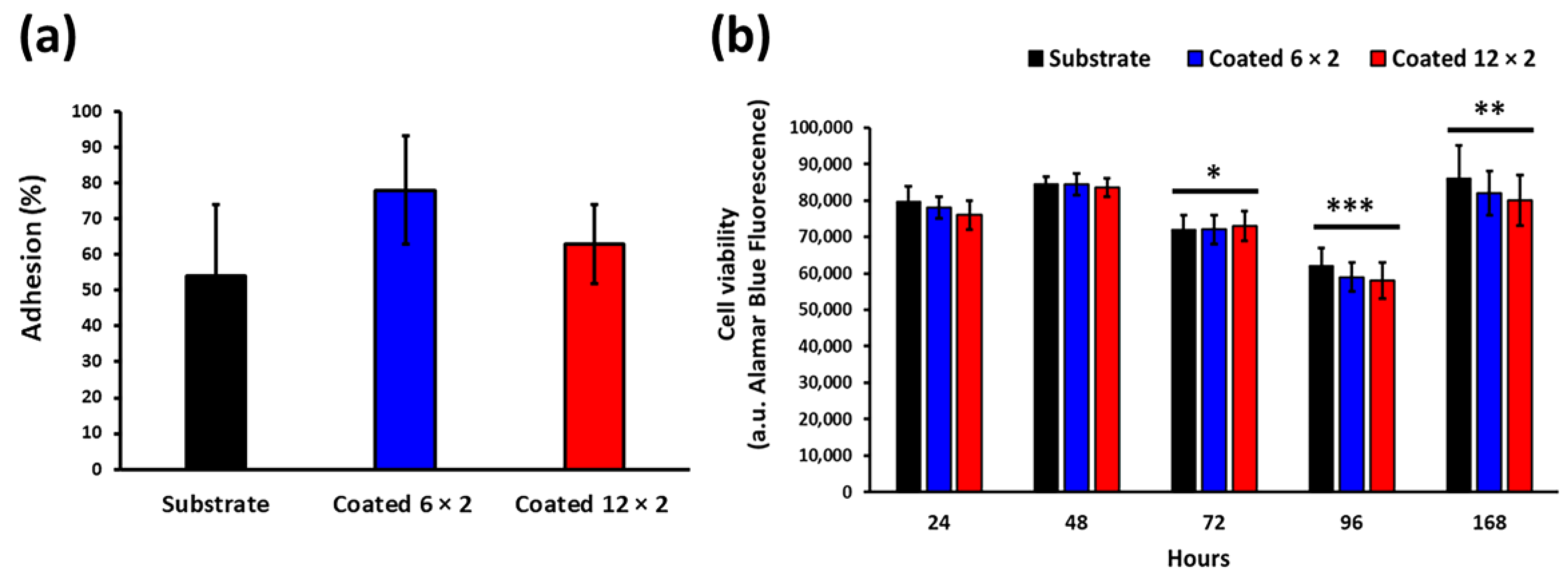

3.8. In Vitro Viability Tests with the MG-63 Cell Line

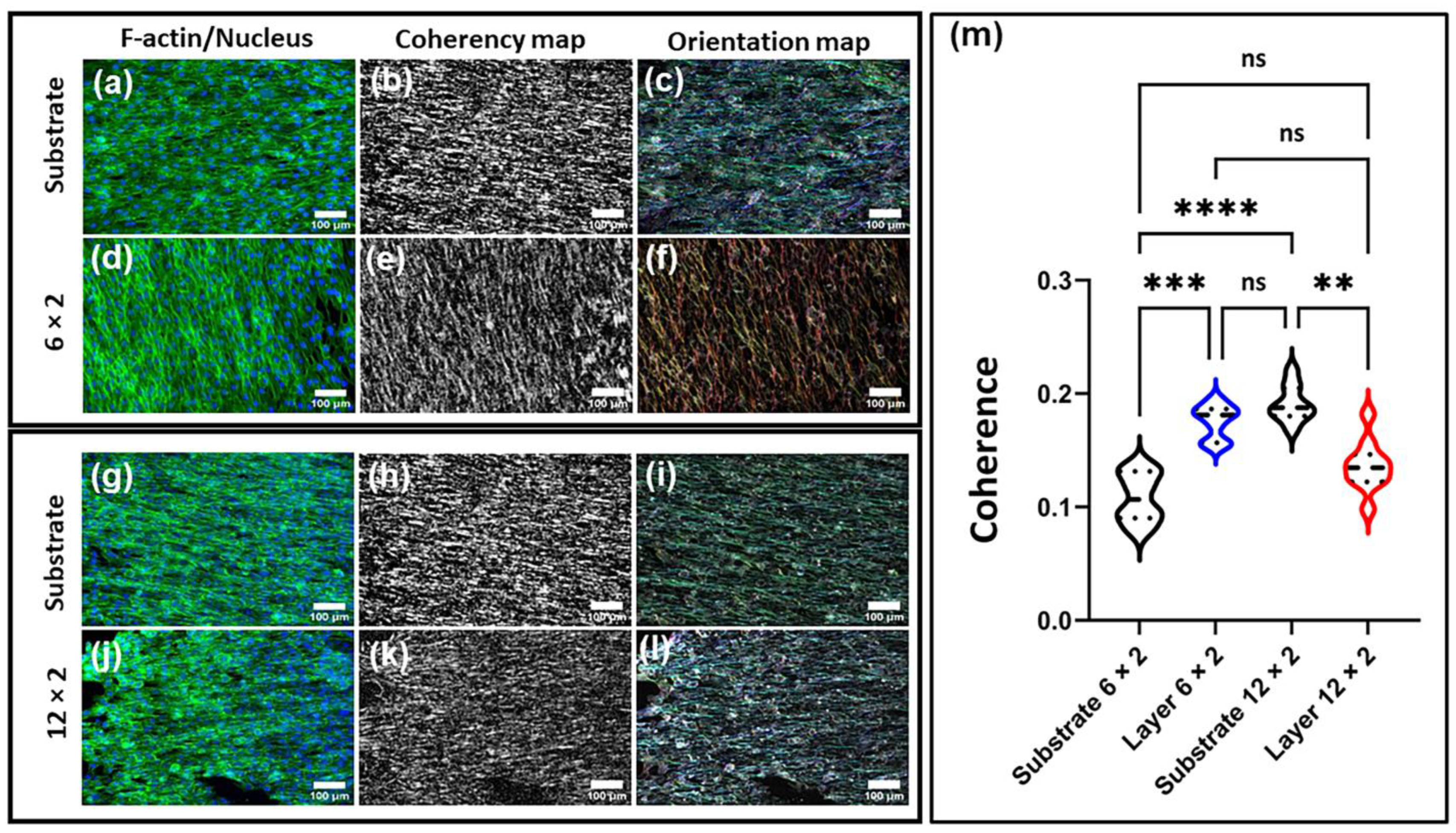

3.9. Cell Morphology

3.10. Osteoblastic Differentiation

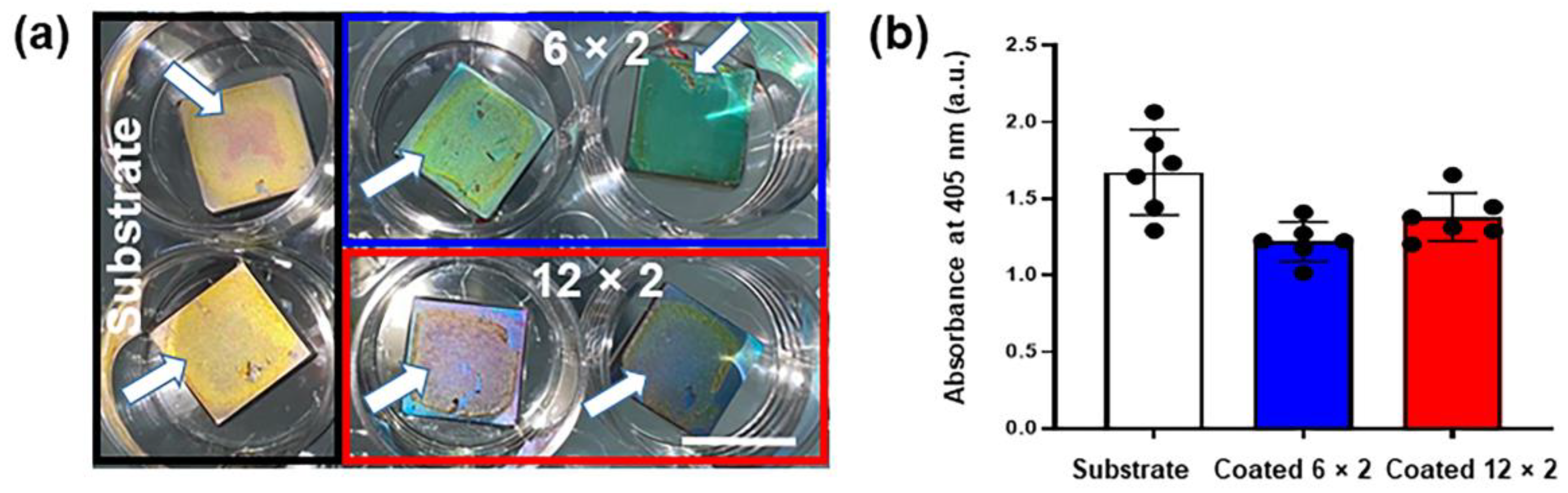

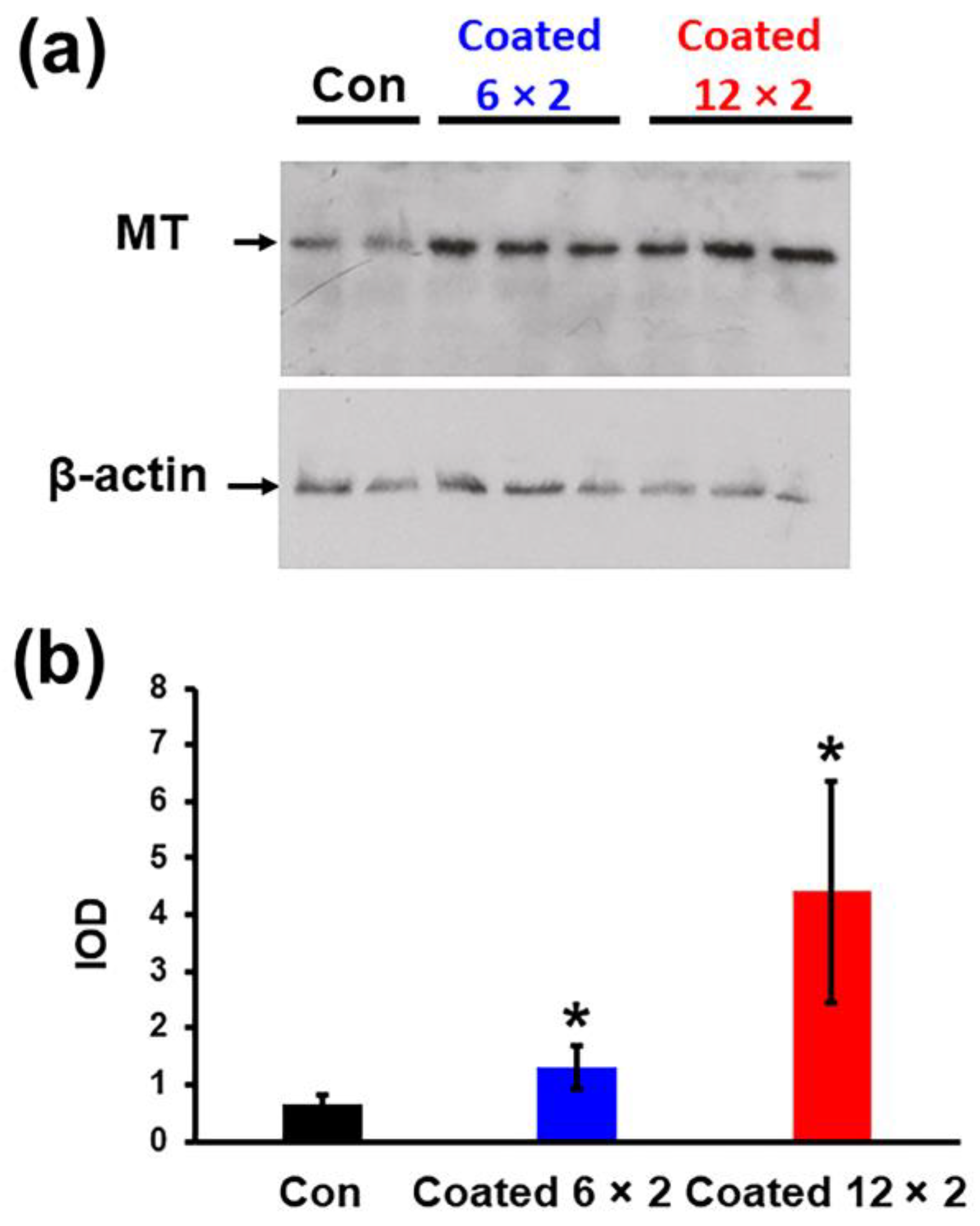

3.11. Metallothionein Response

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duske, K.; Jablonowski, L.; Koban, I.; Matthes, R.; Holtfreter, B.; Sckell, A.; Nebe, J.B.; von Woedtke, T.; Weltmann, K.D.; Kocher, T. Cold atmospheric plasma in combination with mechanical treatment improves osteoblast growth on biofilm covered titanium discs. Biomaterials 2015, 52, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, H.; Ma, D.; Wang, Z.; Liang, H. Recent Advances in Copper-Doped Titanium Implants. Materials 2022, 15, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeque, B.; Hartman, Z.; Noshchenko, A.; Cruse, M. Infection After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2014, 37, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.; Mumjitha, M.S. Fabrication of biopolymers reinforced TNT/HA coatings on Ti: Evaluation of its corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 153, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nine, M.J.; Choudhury, D.; Hee, A.C.; Mootanah, R.; Osman, N.A.A. Wear debris characterization and corresponding bio-logical response: Artificial hip and knee joints. Materials 2014, 7, 980–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartini, I.; Khairani, I.Y.; Triyana, K.; Wahyuni, S. Nanostructured titanium dioxide for functional coatings. In Titanium Dioxide: Material for a Sustainable Environment; Intech Open: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenau, F.; Mittelmeier, W.; Detsch, R.; Haenle, M.; Stenzel, F.; Ziegler, G.; Gollwitzer, H. A novel antibacterial titania coating: Metal ion toxicity and in vitro surface colonization. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, R.; Fu, S.; Qin, G. Antibacterial metals and alloys for potential biomedical implants. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 2569–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Ayre, W.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Dong, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, X. Enhanced functionalities of biomaterials through metal ion surface modification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1522442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.; Nagay, B.; Dini, C.; Souza, J.; Rangel, E.; da Cruz, N. Copper source determines chemistry and topography of implant coatings to optimally couple cellular responses and antibacterial activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 134, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. The dual function of Cu-doped TiO2 coatings on titanium for application in percutaneous implants. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3788–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, A.M.; Williamson, B.A.D.; Sathasivam, S.S.; Kafizas, A.; Alqahtani, M.; Sotelo-Vazquez, C.; Buckeridge, J.; Wu, J.; Nair, S.P.; Scanlon, D.O.; et al. Enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial ability of Cu-Doped anatase TiO2 thin films: Theory and experiment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 15348–15361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmasebizad, N.; Hamedani, M.T.; Ghazani, M.S.; Pazhuhanfar, Y. Photocatalytic activity and antibacterial behavior of TiO2 coatings co-doped with copper and nitrogen via sol–gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 93, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, B.C.; Massar, C.J.; Gleason, M.A.; Cote, D.L. On the emergence of antibacterial and antiviral copper cold spray coatings. J. Biol. Eng. 2021, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, H.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Qin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Ren, L.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of osteogenesis and antibacterial activity of Cu-bearing Ti alloy in a bone defect model with infection in vivo. J. Orthop. Transl. 2021, 27, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, S.; Yang, L.; Qin, G.; Zhang, E. A nano-structured TiO2/CuO/Cu2O coating on Ti-Cu alloy with dual function of antibacterial ability and osteogenic activity. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 97, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Qin, G.; Zhang, E. Enhanced antibacterial activity of Ti-Cu alloy by selective acid etching. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 421, 127478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Shi, A.; Wang, R.; Nie, J.; Qin, G.; Chen, D.; Zhang, E. The Influence of Copper Content on the Elastic Modulus and Antibacterial Properties of Ti-13Nb-13Zr-xCu Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Tian, L.; Ma, Y.; Tang, B. Microstructure and antibacterial properties of Cu-doped TiO2 coating on titanium by micro-arc oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hang, R.; Tang, B. One-step fabrication of cytocompatible micro/nano-textured surface with TiO2 mesoporous arrays on titanium by high current anodization. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 199, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Qian, H.; She, W.; Pan, H.; Wen, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X. Antibacterial property, angiogenic and osteogenic activity of Cu-incorporated TiO2 coating. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 6738–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Kim, J.I.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Mechanical Properties and Shape Memory Behavior of Ti-Nb Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2004, 45, 2443–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovidis, I.; Delimaris, I.; Piperakis, S.M. Copper and its complexes in medicine: A biochemical approach. Mol. Biol. Int. 2011, 2011, 594529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, J.F.; Aperador, W.; Caicedo, J.C.; Alba, N.C.; Amaya, C. Structural, mechanical and tribological behavior of TiCN, CrAlN and BCN coatings in lubricated and non-lubricated environments in manufactured devices. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 252, 123164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, S.; Zamani Meymian, M.R.; Ghaffarinejad, A. Effect of radiofrequency power sputtering on silver-palladium nano-coatings for mild steel corrosion protection in 3.5% NaCl solution. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 8406–8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranak, V.; Wulff, H.; Ksirova, P.; Zietz, C.; Drache, S.; Cada, M.; Hubicka, Z.; Bader, R.; Tichy, M.; Helm, C.A.; et al. Ionized vapor deposition of antimicrobial Ti–Cu films with controlled copper release. Thin Solid Film. 2014, 550, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norambuena, G.A.; Patel, R.; Karau, M.; Wyles, C.C.; Jannetto, P.J.; Bennet, K.E.; Hanssen, A.D.; Sierra, R.J. Antibacterial and Biocompatible Titanium-Copper Oxide Coating May Be a Potential Strategy to Reduce Periprosthetic Infection: An In Vitro Study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shuyuan, Z.; Liu, H.; Ren, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of surface roughening on antibacterial and osteogenic properties of TiCu alloys with different Cu contents. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 88, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, T.A.; O’Keefe, R.J.; Buckwalter, J.A. Orthopaedic Basic Science: Foundations of Clinical Practice; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2007; 465p. [Google Scholar]

- Ilievska, I.; Ivanova, V.; Dechev, D.; Ivanov, N.; Ormanova, M.; Nikolova, M.P.; Handzhiyski, Y.; Andreeva, A.; Valkov, S.; Apostolova, M.D. Influence of Thickness on the Structure and Biological Response of Cu-O Coatings Deposited on cpTi. Coatings 2024, 14, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkov, S.; Parshorov, S.; Andreeva, A.; Bezdushnyi, R.; Nikolova, M.; Dechev, D.; Ivanov, N.; Petrov, P. Influence of Electron Beam Treatment of Co–Cr Alloy on the Growing Mechanism, Surface Topography, and Mechanical Properties of Deposited TiN/TiO2 Coatings. Coatings 2019, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesan, S.; Gehrig, J.; Thomas, L.S.V. Virtual Orientation Tools (VOTj): Fiji plugins for object centering and alignment. Micropubl. Biol. 2024, 2024, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, M.; Nachev, C.; Koleva, M.; Bontchev, P.R.; Kehaiov, I. New competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for determination of metallothionein in tissue and sera. Talanta 1998, 46, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, K.; Chandran, K.R. Synthesis of ductile titanium–titanium boride (Ti-TiB) composites with a beta-titanium matrix: The nature of TiB formation and composite properties. Metall. Mater. Trans. 2003, 34, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, P.; Dechev, D.; Ivanov, N.; Hikov, T.; Valkov, S.; Nikolova, M.; Yankov, E.; Parshorov, S.; Bezdushnyi, R.; Andreeva, A. Study of the influence of electron beam treatment of Ti5Al4V substrate on the mechanical properties and surface topography of multilayer TiN/TiO2 coatings. Vacuum 2018, 154, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Niinomi, M.; Akahori, T. Effects of Ta content on Young’s modulus and tensile properties of binary Ti–Ta alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Welsch, G. Young’s modulus and damping of Ti6Al4V alloy as a function of heat treatment and oxygen concentration. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1990, 128, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanova, I.; Kelly, P.; Burova, M.; Andreeva, A.; Stefanova, B. Influence of thickness on the crystallography and surface topography of TiN nano-films deposited by reactive DC and pulsed magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 5333–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjan, P.; Drnovšek, A.; Gselman, P.; Čekada, M.; Panjan, M. Review of Growth Defects in Thin Films Prepared by PVD Techniques. Coatings 2020, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; He, Q. Microstructure and properties of monolayer, bilayer and multilayer Ta2O5-based coatings on biomedical Ti-6Al-4V alloy by magnetron sputtering. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, M.; Atapour, M.; Ashrafizadeh, F.; Elmkhah, H.; Di Confiengo, G.; Ferraris, S.; Perero, S.; Cardu, M.; Spriano, S. Nanostructured multilayer CAE-PVD coatings based on transition metal nitrides on Ti6Al4V alloy for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 23367–23382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, F.; Gittens, R.A.; Scheideler, L.; Marmur, A.; Boyan, B.D.; Schwartz, Z.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J. A review on the wettability of dental implant surfaces I: Theoretical and experimental aspects. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2894–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.J.; Clegg, R.E.; Leavesley, D.I.; Pearcy, M.J. Mediation of biomaterial-cell interactions by adsorbed proteins: A review. Tissue Eng. 2005, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Azeredo, J.; Teixeira, P.; Fonseca, A.P. The role of hydrophobicity in bacterial adhesion. In Biofilm Community Interactions: Chance or Necessity? Gilbert, P., Allison, D., Brading, M., Verran, J., Walker, J., Eds.; BioLine: London, UK, 2001; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Yang, H.; Du, C.; Fu, X.; Zhao, N.; Xu, S.; Cui, F.; Mao, C.; Wang, Y. Directing the fate of human and mouse mesenchymal stem cells by hydroxyl–methyl mixed self-assembled monolayers with varying wettability. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 4794–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Carrasco, B.; Lemos, B.F.; Herrero-Climent, M.; Gil Mur, F.J.; Ríos-Santos, J.V. Effect of the Acid-Etching on Grit-Blasted Dental Implants to Improve Osseointegration: Histomorphometric Analysis of the Bone-Implant Contact in the Rabbit Tibia Model. Coatings 2021, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpara, J.; Chawla, V.; Chandra, R. Investigation of tantalum oxynitride for hard and anti-corrosive coating application in diluted hydrochloric acid solutions. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 23, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Pathak, L.C.; Singh, R. Response of boride coating on the Ti-6Al-4V alloy to corrosion and fretting corrosion behavior in Ringer’s solution for bio-implant application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 433, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryl, J.; Wysocka, J.; Slepski, P.; Darowicki, K. Instantaneous impedance monitoring of synergistic effect between cavitation erosion and corrosion processes. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 203, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, Z.; Elmkhah, H.; Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Babaei, K.; Meghdari, M. Comparing the electrochemical behaviour of applied CrN/TiN nanoscale multilayer and TiN single-layer coatings deposited by CAE-PVD method. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2020, 8, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Leygraf, C.; Thierry, D.; Ektessabi, A.M. Corrosion resistance for biomaterial applications of TiO2 films deposited on titanium and stainless steel by ion-beam-assisted sputtering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997, 35, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreto, J.A.; Marino, C.E.B.; Bose Filho, W.W.; Rocha, L.A.; Fernandes, J.C.S. SVET, SKP and EIS study of the corrosion be-haviour of high strength Al and Al-Li alloys used in aircraft fabrication. Corros. Sci. 2014, 84, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Hang, R.; Huang, X.; Yao, X.; Zhang, X. Cu and Si co-doped microporous TiO2 coating for osseointegration by the coordinated stimulus action. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 503, 144072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nast, S.; Fassbender, M.; Bormann, N.; Beck, S.; Montali, A.; Lucke, M.; Schmidmaier, G.; Wildemann, B. In vivo quantification of gentamicin released from an implant coating. J. Biomater. Appl. 2016, 31, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetrick, E.M.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Reducing implant-related infections: Active release strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Akhavan, B.; Jing, F.; Cheng, D.; Sun, H.; Xie, D.; Leng, Y.; Bilek, M.M.; Huang, N. Catalytic formation of nitric oxide mediated by Ti–cu coatings provides multifunctional interfaces for cardiovascular applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1701487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranak, V.; Wulff, H.; Rebl, H.; Zietz, C.; Arndt, K.; Bogdanowicz, R.; Nebe, B.; Bader, R.; Podbielski, A.; Hubicka, Z.; et al. Deposition of thin titanium–copper films with antimicrobial effect by advanced magnetron sputtering methods. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2011, 31, 1512–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Han, Q.; Yu, K.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Q. Antibacterial activities against porphyromonas gingivalis and biological characteristics of copper-bearing PEO coatings on magnesium. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenyuan, W.; Wei, X.; Zhong, L.; Chan, C.-L.; Li, H.; Sun, H. Metal-based approaches for the fight against antimicrobial resistance: Mechanisms, opportunities, and challenges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 12361–12380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, L.A.; Skoda, M.W.A.; Le Brun, A.P.; Ciesielski, F.; Kuzmenko, I.; Holt, S.A.; Lakey, J.H. Effect of divalent cation removal on the structure of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane models. Langmuir 2015, 31, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugala, N.; Vu, D.; Parkins, M.D.; Turner, R.J. Specificity in the susceptibilities of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates to six metal antimicrobials. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teksoy, A.; Özyiğit, M.E. A Study on the Use of Copper Ions for Bacterial Inactivation in Water. Water 2025, 17, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu Eser, O.; Ergin, A.; Hascelik, G. Antimicrobial activity of copper alloys against invasive multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 71, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, A.; Bloise, N.; Fiorilli, S.; Novajra, G.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Bruni, G.; Torres-Pardo, A.; González-Calbet, J.M.; Visai, L.; Vitale-Brovarone, C. Copper-containing mesoporous bioactive glass nanoparticles as multifunctional agent for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhmalev, P.; Yadroitsev, I.; Yadroitsava, I.; De Smidt, O. Functionalization of Biomedical Ti6Al4V via In Situ Alloying by Cu during Laser Powder Bed Fusion Manufacturing. Materials 2017, 10, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Umar, E.; Raza, A.; Haider, A.; Naz, S.; Ul-Hamid, A.; Haider, J.; Shahzadi, I.; Hassan, J.; Ali, S. Dye degradation performance, bactericidal behavior and molecular docking analysis of Cu-doped TiO2 nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 24215–24233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, S.; Spriano, S. Antibacterial titanium surfaces for medical implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 61, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.; Allan, R.N.; Howlin, R.P.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Targeting microbial biofilms: Current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadinasab, S.; Williams, M.D.; Falkinham, J.O., III; Ducker, W.A. Antimicrobial mechanism of cuprous oxide (Cu2O) coatings. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 652, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Villani, S.; Mansi, A.; Marcelloni, A.M.; Chiominto, A.; Amori, I.; Proietto, A.R.; Calcagnile, M.; Alifano, P.; Bagheri, S.; et al. Antimicrobial and superhydrophobic CuONPs/TiO2 hybrid coating on polypropylene substrates against biofilm formation. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 45376–45385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, C.E.; Lam, E.W.; Elowsky, C.G.; Quaranta, D.; Domaille, D.W.; Chang, C.J.; Grass, G. Bacterial killing by dry metallic copper surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiger, M.; Solioz, M.; Edongué, H.; Arzt, E.; Schneider, A.S. Surface structure influences contact killing of bacteria by copper. Microbiologyopen 2014, 3, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, S.; Hans, M.; Mücklich, F.; Solioz, M. Contact killing of bacteria on copper is suppressed if bacterial-metal contact is prevented and is induced on iron by copper ions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2605–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, C.; Abicht, H.K.; Solioz, M. Killing of bacteria by copper surfaces involves dissolved copper. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 4099–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.; Toro, M.; Jacob, R.; Navarrete, P.; Troncoso, M.; Figueroa, G.; Reyes-Jara, A. Antimicrobial effect of copper surfaces on bacteria isolated from poultry meat. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.J.S.; Kianvash, A.; Rezvani, M.; Memar, M.Y. Biological properties of copper: Antibacterial, osteogenesis of biomaterials. Biochem. Biophys Rep. 2025, 44, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngece, K.; Khwaza, V.; Paca, A.M.; Aderibigbe, B.A. The Antimicrobial Efficacy of Copper Complexes: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhu, L.; Tian, C.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Cai, G. Study of Anticorrosion and Antifouling Properties of a Cu-Doped TiO2 Coating Fabricated via Micro-Arc Oxidation. Materials 2024, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Helvert, S.; Storm, C.; Friedl, P. Mechanoreciprocity in cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashoff, C.; Hoffman, B.; Brenner, M.; Zhou, R.; Parsons, M.; Yang, M.T.; McLean, M.A.; Sligar, S.G.; Chen, C.S.; Ha, T.; et al. Measuring mechanical tension across vinculin reveals regulation of focal adhesion dynamics. Nature 2010, 466, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalapathy, S.; Sreekumar, D.; Ratna, P.; Shivashankar, G.V. Actomyosin contractility as a mechanical checkpoint for cell state transitions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, G.; Oliver-De La Cruz, J.; Vrbsky, J.; Martini, C.; Pribyl, J.; Skládal, P.; Pešl, M.; Caluori, G.; Pagliari, S.; Martino, F.; et al. YAP regulates cell mechanics by controlling focal adhesion assembly. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, I.; McCollum, D. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 17693–17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagia, J.Z.; Ivaska, J.; Roca-Cusachs, P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Cesarovic, N.; Falk, V.; Mazza, E.; Giampietro, C. Mechanical factors influence β-catenin localization and barrier properties. Integr. Biol. 2024, 16, zyae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | 6 × 2 Coating | 12 × 2 Coating | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt% | Sigma | wt% | Sigma | |

| Ti | 41.79 | 0.66 | 30.12 | 0.68 |

| Cu | 29.83 | 0.59 | 40.10 | 0.67 |

| O | 28.38 | 0.6 | 29.78 | 0.6 |

| Total | 100 | - | 100 | - |

| Sample | Sa, nm | Sz, µm | Ssk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | 20.96 ± 6.06 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| Coated 6 × 2 | 45.10 ± 14.34 | 0.34 ± 0.14 | 1.03 ± 0.15 |

| Coated 12 × 2 | 49.17 ± 16.04 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 0.30 ± 0.07 |

| Sample | HK0.005 (kgf mm−2) | FC (N) | COF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | 866.5 ± 68 | - | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| Coated 6 × 2 | 1429 ± 79 | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| Coated 12 × 2 | 2434 ± 93 | 14.8 ± 0.5 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| Sample | Ecorr (mV vs. SCE) | jcorr (10−9 A cm−2) | P.E. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti6Al4V | 39.6 | 434 | - |

| Coated 6 × 2 | −59.8 | 34.6 | 92 |

| Coated 12 × 2 | −36.7 | 24.9 | 94.3 |

| Sample Time | Ti6Al4V | Coated 6 × 2 | Coated 12 × 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 168 h | 24 h | 168 h | 24 h | 168 h | |

| Qp, (Ω−1cm−2sn) | 2.1 × 10−3 | 7.3 × 10−7 | 2.5 × 10−6 | 8.3 × 10−6 | 2 × 10−6 | 2.9 × 10−6 |

| n1 | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.95 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.75 |

| Rp, (Ωcm2) | 17.8 | 17.4 | 1.9 × 107 | 6 × 103 | 2.1 × 107 | 1.1 × 104 |

| Qb, (Ω−1cm−2sn) | 1.5 × 10−5 | 1.3 × 10−5 | 5.3 × 10−6 | 1.7 × 10−5 | 7.5 × 10−7 | 6.9 × 10−6 |

| n2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| Rb, (Ωcm2) | 2.8 × 106 | 1.3 × 107 | 7.9 × 103 | 3.6 × 106 | 9.2 × 103 | 1.9 × 108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Valkov, S.; Nikolova, M.P.; Dimitrova, T.V.; Stancheva, M.E.; Dechev, D.; Ivanov, N.; Handzhiyski, Y.; Andreeva, A.; Ormanova, M.; Anchev, A.; et al. Multilayer Ti–Cu Oxide Coatings on Ti6Al4V: Balancing Antibacterial Activity, Mechanical Strength, Corrosion Resistance, and Cytocompatibility. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010016

Valkov S, Nikolova MP, Dimitrova TV, Stancheva ME, Dechev D, Ivanov N, Handzhiyski Y, Andreeva A, Ormanova M, Anchev A, et al. Multilayer Ti–Cu Oxide Coatings on Ti6Al4V: Balancing Antibacterial Activity, Mechanical Strength, Corrosion Resistance, and Cytocompatibility. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleValkov, Stefan, Maria P. Nikolova, Tanya V. Dimitrova, Maria Elena Stancheva, Dimitar Dechev, Nikolay Ivanov, Yordan Handzhiyski, Andreana Andreeva, Maria Ormanova, Angel Anchev, and et al. 2026. "Multilayer Ti–Cu Oxide Coatings on Ti6Al4V: Balancing Antibacterial Activity, Mechanical Strength, Corrosion Resistance, and Cytocompatibility" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010016

APA StyleValkov, S., Nikolova, M. P., Dimitrova, T. V., Stancheva, M. E., Dechev, D., Ivanov, N., Handzhiyski, Y., Andreeva, A., Ormanova, M., Anchev, A., & Apostolova, M. D. (2026). Multilayer Ti–Cu Oxide Coatings on Ti6Al4V: Balancing Antibacterial Activity, Mechanical Strength, Corrosion Resistance, and Cytocompatibility. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010016