Hexapeptide-Liposome Nanosystem for the Delivery of Endosomal pH Modulator to Treat Acute Lung Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of HCQ-L and HCQ-L-P12

2.3. Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Loading Efficiency of HCQ

2.4. Drug Release Profile

2.5. Culture of THP-1 Cell-Derived Macrophages

2.6. Reporter Cell Assay for the NF-kB/AP-1 and IRF Activation Analysis

2.7. Immunoblotting Analysis

2.8. Cytokine Analysis

2.9. Endosomal pH Assessment

2.10. LPS-Induced ALI Mouse Model

2.11. BALF Collection and Differential Cell Counting

2.12. Lung Histology and Injury Score

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

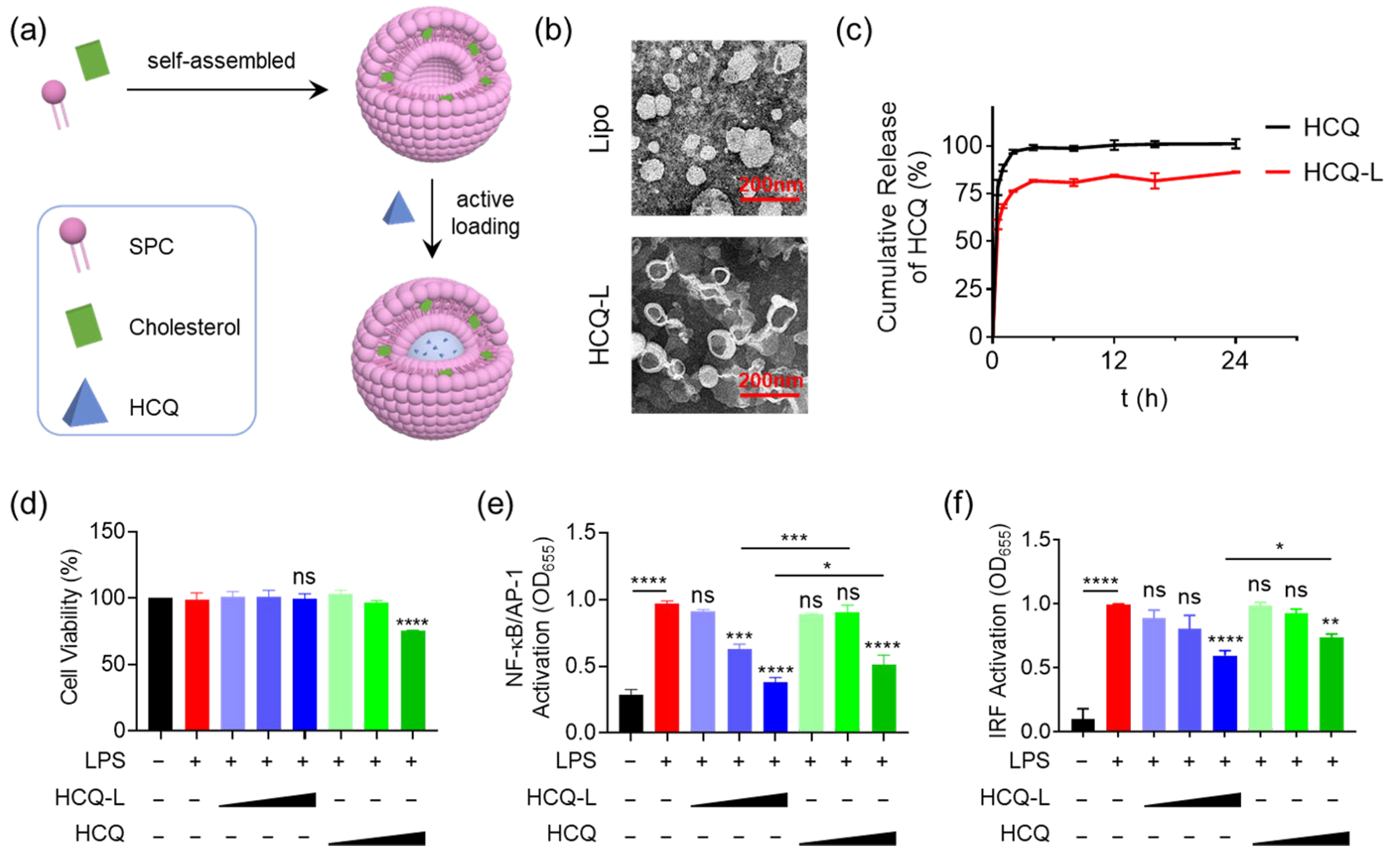

3.1. Fabrication of the HCQ-Encapsulated Liposomal Nanosystem and Evaluation of Its Inhibitory Activity on TLR4 Signaling Pathway

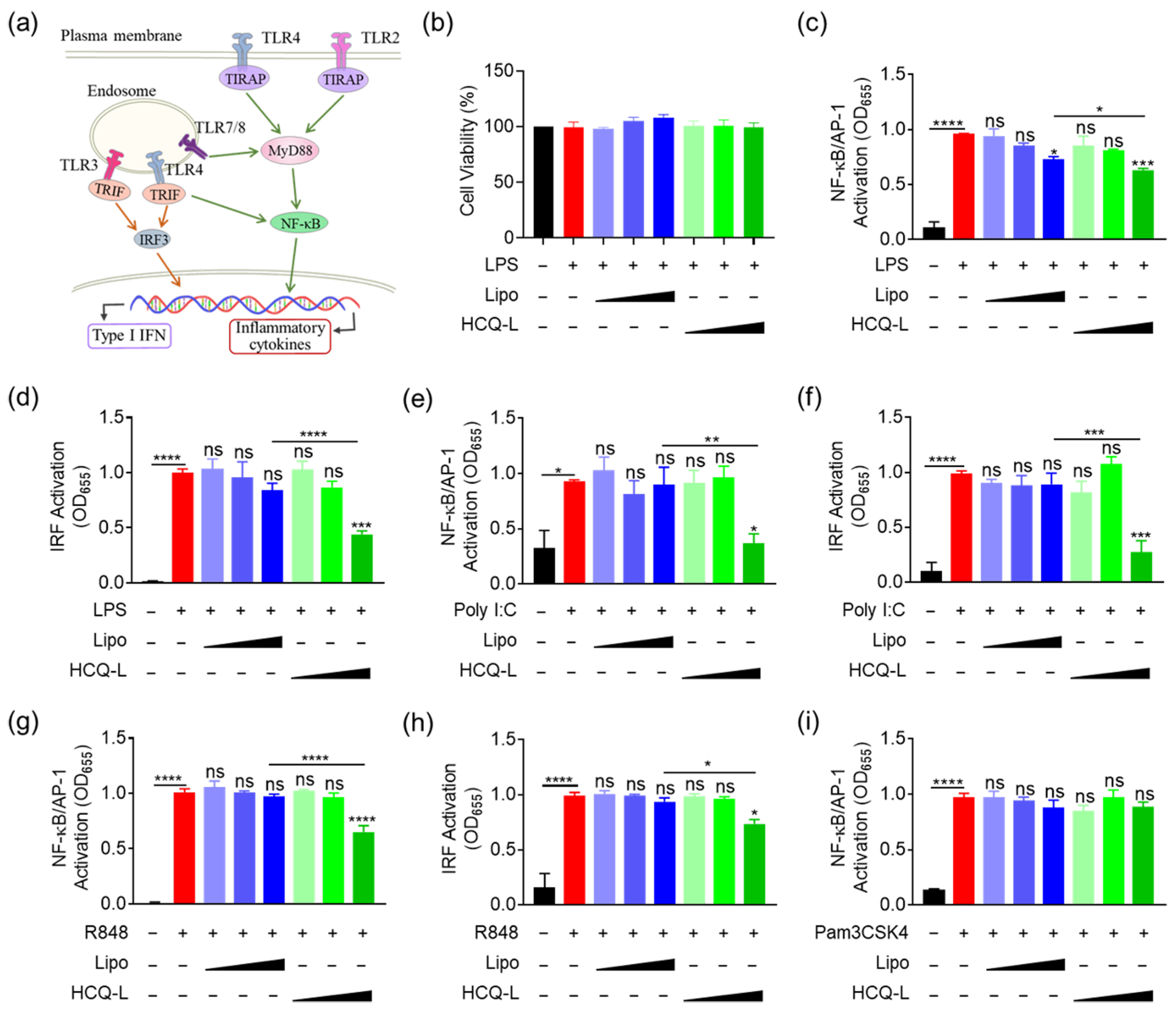

3.2. HCQ-L Had a Broad Inhibitory Activity on the Endosomal TLR Pathways

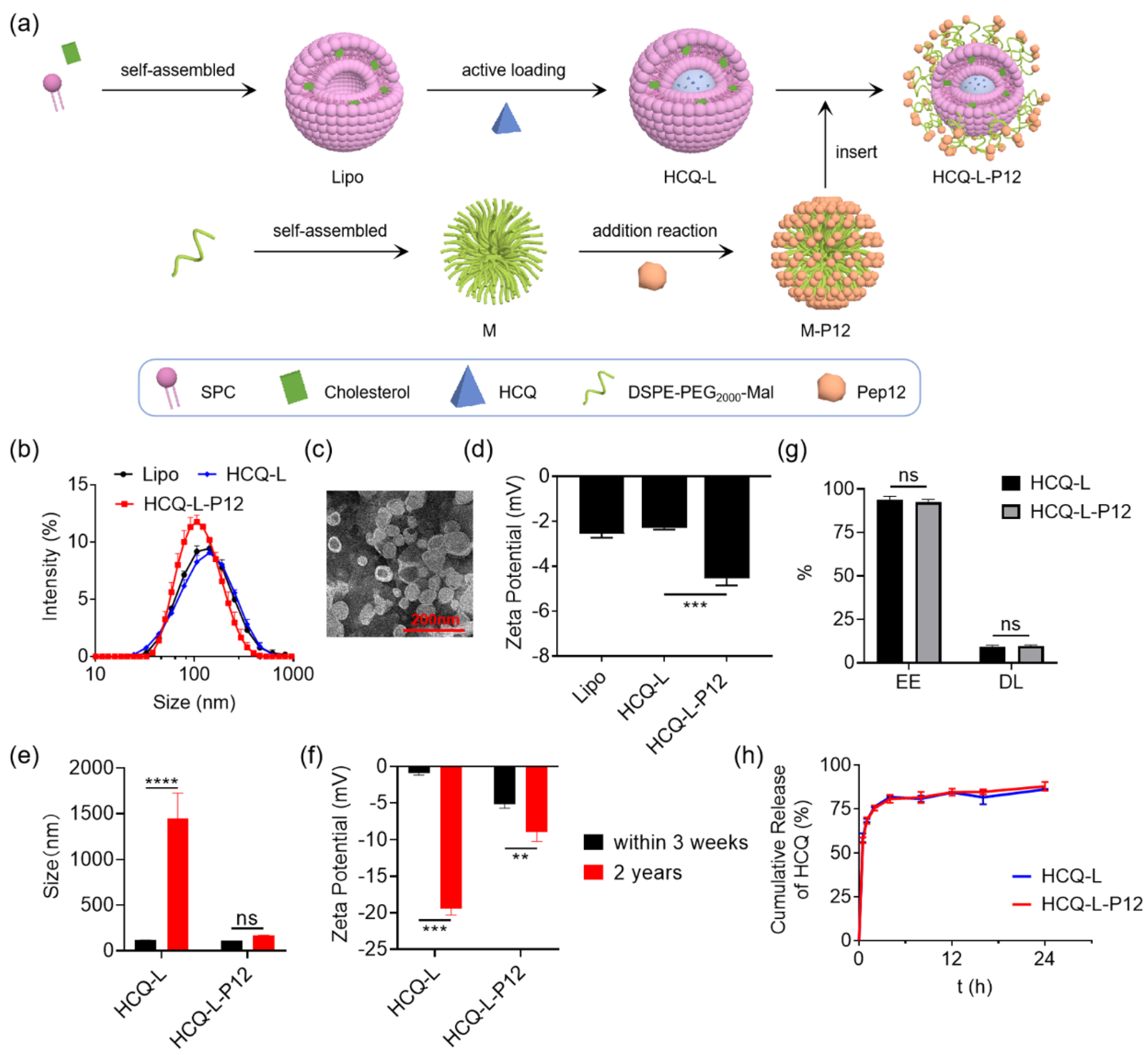

3.3. Fabrication and Characterization of Hexapeptide-Modified Liposomal Nanosystem

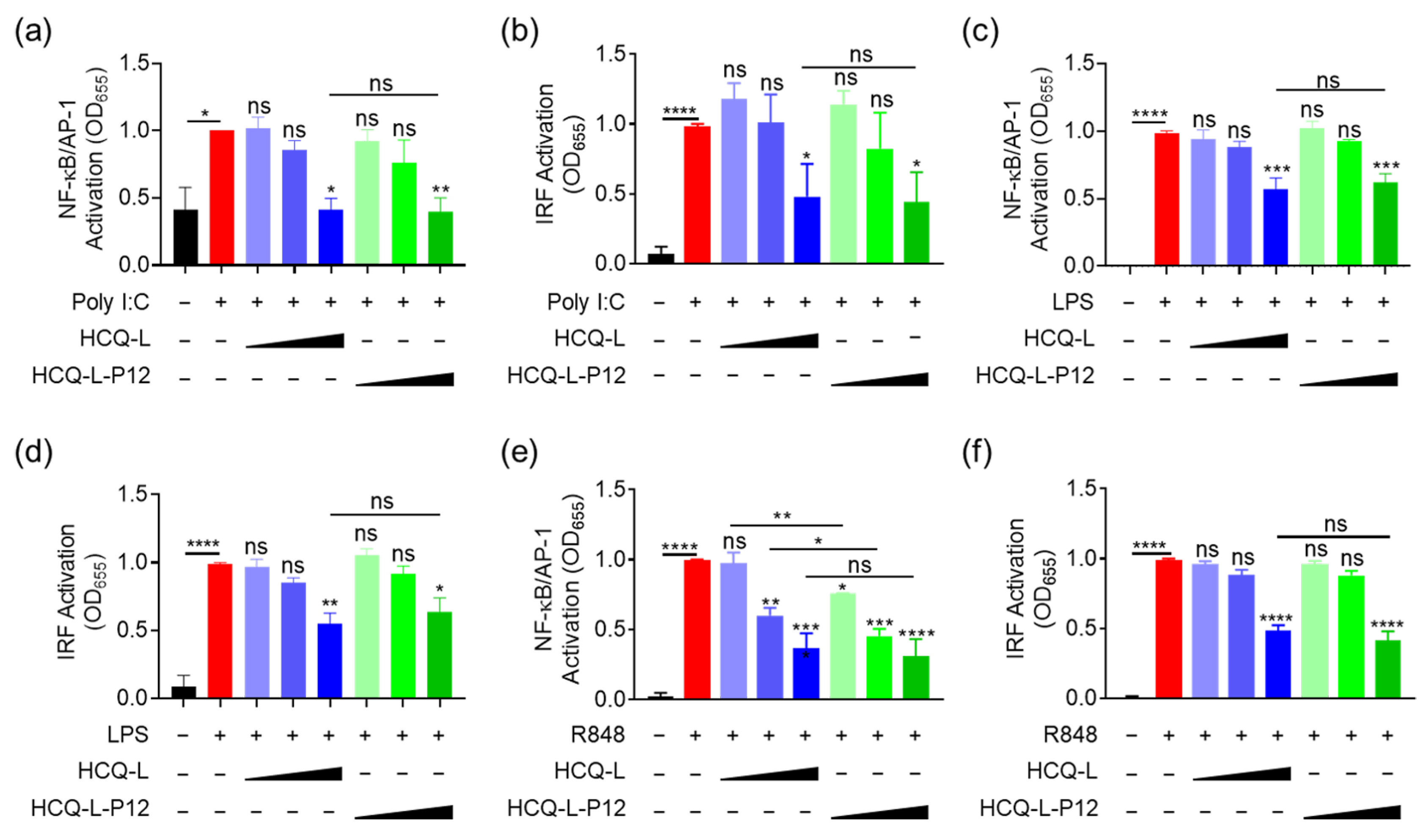

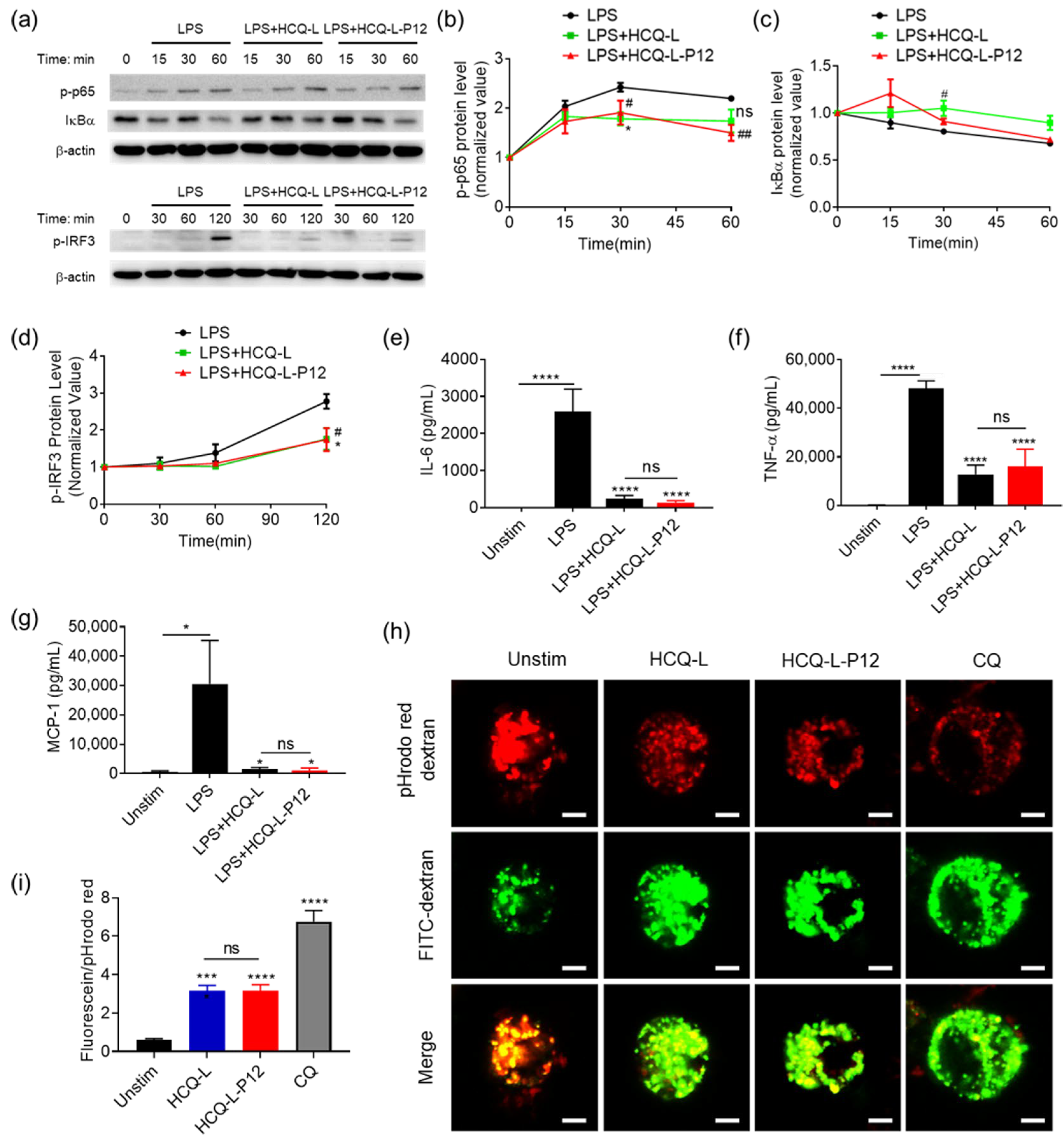

3.4. The Inhibitory Activity of HCQ-L-P12 on Endosomal TLR Signaling, Cytokine Production, and Endosomal Acidification in Macrophages

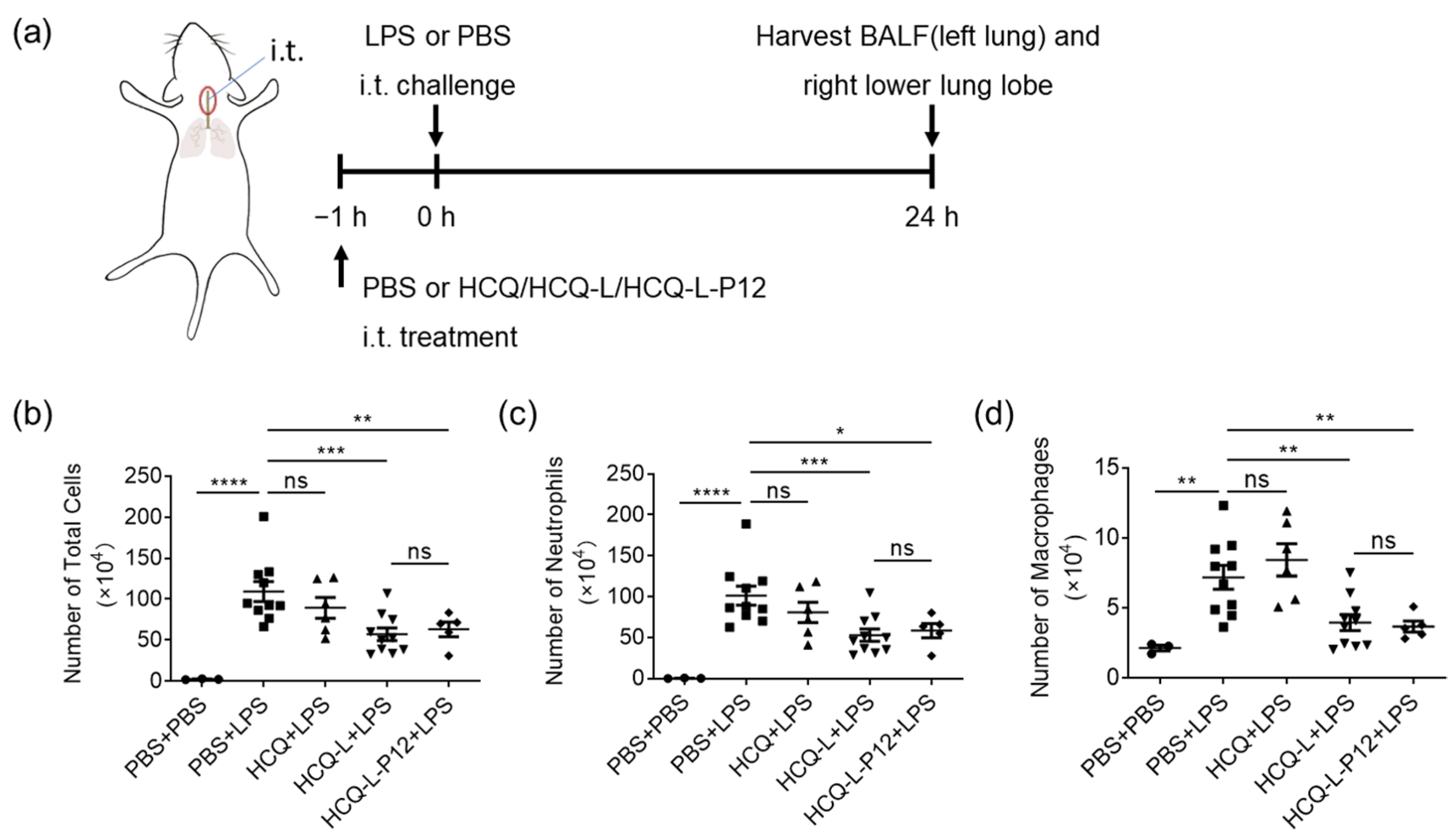

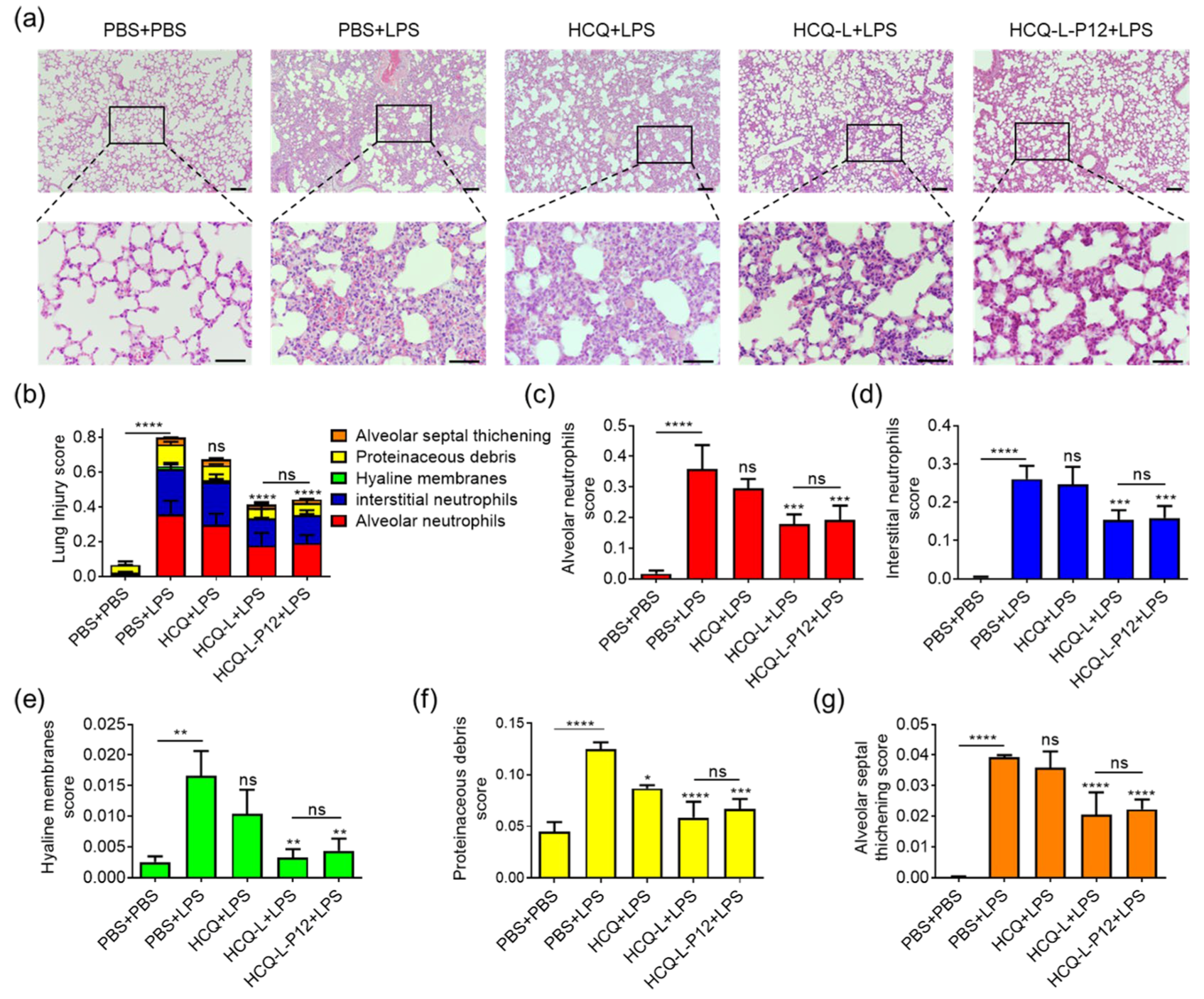

3.5. HCQ-L and HCQ-L-P12 Alleviated Lung Inflammation in the LPS-Induced ALI Mouse Model

4. Discussion

4.1. The Important Role of Endosomal TLR Hyperactivation in ALI

4.2. The Mechanism of Action for the Nanoformulation-Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy of HCQ in ALI

4.3. Broad Therapeutic Prospects of the Peptide-Modified Liposomal Nanosystem for Endosomal pH-Modulating Immunotherapy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thompson, B.T.; Chambers, R.C.; Liu, K.D. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, M.A.; Arabi, Y.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bernard, G.; Bersten, A.D.; Brochard, L.J.; Calfee, C.S.; Combes, A.; Daniel, B.M.; Ferguson, N.D.; et al. A new global definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 209, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Tan, D.; Liu, B.; Xiao, G.; Gong, F.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, L.; Zheng, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): From mechanistic insights to therapeutic strategies. MedComm 2025, 6, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Tang, S.; Yao, P.; Zhou, T.; Niu, Q.; Liu, P.; Tang, S.; Chen, Y.; Gan, L.; Cao, Y. Advances in acute respiratory distress syndrome: Focusing on heterogeneity, pathophysiology, and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, S.; Pozzetti, L.; Papa, A.; Carullo, G.; Gemma, S.; Butini, S.; Campiani, G.; Relitti, N. Modulation of the innate immune response by targeting Toll-like receptors: A perspective on their agonists and antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root-Bernstein, R. Innate receptor activation patterns involving TLR and NLR synergisms in COVID-19, ALI/ARDS and sepsis cytokine storms: A review and model making novel predictions and therapeutic suggestions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gies, V.; Bekaddour, N.; Dieudonné, Y.; Guffroy, A.; Frenger, Q.; Gros, F.; Rodero, M.P.; Herbeuval, J.P.; Korganow, A.S. Beyond anti-viral effects of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferner, R.E.; Aronson, J.K. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 369, m1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevaratnam, K. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19: Implications for cardiac safety. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2020, 6, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horby, P.; Mafham, M.; Linsell, L.; Bell, J.L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.R.; Wiselka, M.; Ustianowski, A.; Elmahi, E.; Prudon, B.; et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2030. [Google Scholar]

- Large, D.E.; Abdelmessih, R.G.; Fink, E.A.; Auguste, D.T. Liposome composition in drug delivery design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 176, 113851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z. Bioresponsive nanoparticles targeted to infectious microenvironments for sepsis management. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1803618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber Raviv, S.; Alyan, M.; Egorov, E.; Zano, A.; Harush, M.Y.; Pieters, C.; Korach-Rechtman, H.; Saadya, A.; Kaneti, G.; Nudelman, I.; et al. Lung targeted liposomes for treating ARDS. J. Control. Release 2022, 346, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadiyan, Z.; Misran, M.; Kalantari, K.; Webster, T.J.; Kia, P.; Basrowi, N.A.; Rasouli, E.; Shameli, K. Advancements in liposomal nanomedicines: Innovative formulations, therapeutic applications, and future directions in precision medicine. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Li, C.; Fan, L.; Lu, H.; Zhan, C.; Zhang, Z. Brain-targeted drug delivery by in vivo functionalized liposome with stable D-peptide ligand. J. Control. Release 2024, 373, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xie, J.; Gao, N.; Feng, H.; Wang, B.; Tian, H.; Wu, C.; Liu, C. Muscle homing peptide modified liposomes loaded with EGCG improved skeletal muscle dysfunction by inhibiting inflammation in aging mice. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, Y.; Qi, J.; Yao, Q.; Xie, J.; Jiang, X. Multi-targeted peptide-modified gold nanoclusters for treating solid tumors in the liver. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210412. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Fung, S.Y.; Xu, S.; Sutherland, D.P.; Kollmann, T.R.; Liu, M.; Turvey, S.E. Amino acid-dependent attenuation of Toll-like receptor signaling by peptide-gold nanoparticle hybrids. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kozicky, L.; Saferali, A.; Fung, S.Y.; Afacan, N.; Cai, B.; Falsafi, R.; Gill, E.; Liu, M.; Kollmann, T.R.; et al. Endosomal pH modulation by peptide-gold nanoparticle hybrids enables potent anti-inflammatory activity in phagocytic immune cells. Biomaterials 2016, 111, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Gao, W.; Xia, F.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Ben, S.; Turvey, S.E.; Yang, H.; Li, Q. Peptide-gold nanoparticle hybrids as promising anti-inflammatory nanotherapeutics for acute lung injury: In vivo efficacy, biodistribution, and clearance. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1800510. [Google Scholar]

- Akira, S.; Takeda, K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, C.; Ergonul, O.; Can, F.; Pang, Z.; et al. LPS adsorption and inflammation alleviation by polymyxin B-modified liposomes for atherosclerosis treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Gong, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; et al. Dual functioned hexapeptide-coated lipid-core nanomicelles suppress Toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory responses through endotoxin scavenging and endosomal pH modulation. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2301230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengottiyan, S.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Jagiełło, K.; Swirog, M.; Puzyn, T. Core, coating, or corona? The importance of considering protein coronas in nano-QSPR modeling of zeta potential. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Gong, T.; Loughran, P.A.; Li, Y.; Billiar, T.R.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Fan, J. Roles of TLR4 in macrophage immunity and macrophage-pulmonary vascular/lymphatic endothelial cell interactions in sepsis. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xiu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, G. The role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 1264913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, M.V.; Thomas, B.; Machado-Aranda, D.; Dolgachev, V.A.; Kumar Ramakrishnan, S.; Talarico, N.; Cavassani, K.; Sherman, M.A.; Hemmila, M.R.; Kunkel, S.L.; et al. Double-stranded RNA interacts with Toll-like receptor 3 in driving the acute inflammatory response following lung contusion. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, e1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Liu, F.; Tang, K. Clinical significance of TLR7/IL-23/IL-17 signaling pathway in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clinics 2024, 79, 100358. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, M.V.; Thomas, B.; Dolgachev, V.A.; Sherman, M.A.; Goldberg, R.; Johnson, M.; Chowdhury, A.; Machado-Aranda, D.; Raghavendran, K. Toll-like receptor-9 (TLR9) is requisite for acute inflammatory response and injury following lung contusion. Shock 2016, 46, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Kuba, K.; Neely, G.G.; Yaghubian-Malhami, R.; Perkmann, T.; van Loo, G.; Ermolaeva, M.; Veldhuizen, R.; Leung, Y.H.; Wang, H.; et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 2008, 133, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejler, G.; Zhao, X.O.; Fagerström, E.; Paivandy, A. Blockade of endolysosomal acidification suppresses TLR3-mediated proinflammatory signaling in airway epithelial cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznik, A.; Bencina, M.; Svajger, U.; Jeras, M.; Rozman, B.; Jerala, R. Mechanism of endosomal TLR inhibition by antimalarial drugs and imidazoquinolines. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, J. PLD4 variants promote SLE via unchecked TLR activation. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión, M.; Juarranz, Y.; Pérez-García, S.; Jimeno, R.; Pablos, J.L.; Gomariz, R.P.; Gutiérrez-Cañas, I. RNA sensors in human osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts: Immune regulation by vasoactive intestinal peptide. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2011, 63, 1626. [Google Scholar]

- Roshan, M.H.; Tambo, A.; Pace, N.P. The role of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Int. J. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1532832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lin, R.; Pang, M.; Sun, L.; Gong, J.; Ma, H.; Fung, S.-Y.; Yang, H. Hexapeptide-Liposome Nanosystem for the Delivery of Endosomal pH Modulator to Treat Acute Lung Injury. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120450

Ji Y, Wang Q, Lin R, Pang M, Sun L, Gong J, Ma H, Fung S-Y, Yang H. Hexapeptide-Liposome Nanosystem for the Delivery of Endosomal pH Modulator to Treat Acute Lung Injury. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120450

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Yuting, Qian Wang, Rujing Lin, Mimi Pang, Liya Sun, Jiameng Gong, Huiqiang Ma, Shan-Yu Fung, and Hong Yang. 2025. "Hexapeptide-Liposome Nanosystem for the Delivery of Endosomal pH Modulator to Treat Acute Lung Injury" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120450

APA StyleJi, Y., Wang, Q., Lin, R., Pang, M., Sun, L., Gong, J., Ma, H., Fung, S.-Y., & Yang, H. (2025). Hexapeptide-Liposome Nanosystem for the Delivery of Endosomal pH Modulator to Treat Acute Lung Injury. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120450