Fracture Load of Polyaryletherketone for 4-Unit Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Grouping and Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Virtual Die Model and Framework Design

Virtual Die Model and Framework Milling and Sample Preparation

2.4. Mechanical Testing

2.5. Fracture Pattern

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fracture Load Testing

3.2. Fracture Pattern

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 3Y zirconia demonstrated the highest fracture resistance but failed in a brittle and catastrophic manner, confirming its suitability for high-stress posterior applications where rigidity is prioritized.

- 4Y zirconia presented a more moderate fracture resistance than 3Y zirconia, making it a reasonable compromise between strength and esthetics, but was mechanically inferior.

- PEKK exhibited the lowest fracture resistance and brittle fracture behavior in FDP form, indicating that design modifications (larger connectors and reinforcement) are necessary for long-span applications.

- Material selection for long-span posterior FDPs should balance fracture load, failure mode, and clinical priorities. Polymer-based frameworks may be advantageous where ductility and reduced catastrophic failure are desired.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAEK | polyaryletherketone |

| PEEK | polyetheretherketone |

| ZrO2 | zirconia |

References

- Farah, J.W.; Craig, R.G.; Meroueh, K.A. Finite Element Analysis of Three- and Four-Unit Bridges. J. Oral Rehabil. 1989, 16, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstiel, S.F. Contemporary Fixed Prosthodontics, 6th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Eichberger, M.; Uhrenbacher, J.; Wimmer, T.; Edelhoff, D.; Schmidlin, P.R. Three-Unit Reinforced Polyetheretherketone Composite FDPs: Influence of Fabrication Method on Load-Bearing Capacity and Failure Types. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rexhepi, I.; Santilli, M.; D’Addazio, G.; Tafuri, G.; Manciocchi, E.; Caputi, S.; Sinjari, B. Clinical Applications and Mechanical Properties of CAD-CAM Materials in Restorative and Prosthetic Dentistry: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, K.J.; Morgano, S.M.; Driscoll, C.F.; Freilich, M.A.; Guckes, A.D.; Kent, L.; Knoernschild, K.L.; McGarry, T.J. The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms: Ninth Edition. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, e1–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, S.K.; Heo, S.J.; Koak, J.Y. Marginal Accuracy and Internal Fit of 3D Printing Laser-Sintered Co–Cr Alloy Copings. Materials 2017, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, W.C.; Kim, J.H. Accuracy Evaluation of Metal Copings Fabricated by Computer-Aided Milling and Direct Metal Laser Sintering Systems. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shillingburg, H.T.; Sather, D.A.; Wilson, E.L.; Cain, J.R.; Mitchell, D.L. Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics, 4th ed.; Quintessence Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, F.; Bahce, E.; Baran, M.C. Mechanical Analysis of Three-Unit Metal-Free Fixed Dental Prostheses Produced in Different Materials with CAD/CAM Technology. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5969–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.; Tobar, C.; Lopez-Suarez, C.; Pelaez, J.; Suarez, M.J. Fracture Load of Metal, Zirconia, and Polyetheretherketone Posterior CAD–CAM Milled Fixed Partial Denture Frameworks. Materials 2021, 14, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitalla, A.D.; Spintig, T.; Kallage, I.; Müller, W.D. Flexural Behavior of PEEK Materials for Dental Application. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, H.; Ulstein, D.M.; Vaage, M.M.; Øilo, M. Internal and Marginal Fit of Cobalt–Chromium Fixed Dental Prostheses Fabricated with Three Different Techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertucci, V.; Marrelli, B.; Ruggiero, R.; Iaquinta, M.; Marenzi, G.; Parisi, G.M.; Gasparro, R.; Pacifici, A.; Palumbo, G.; Sammartino, G.; et al. Comparative in vitro study on biomechanical behavior of zirconia and polyetheretherketone biomaterials exposed to experimental loading conditions in a prototypal simulator. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari, A.; Mantovani, S.; Berzaghi, A.; Bellucci, D.; Bortolini, S.; Cannillo, V. Load bearing capability of three-units 4Y-TZP monolithic fixed dental prostheses: An innovative model for reliable testing. Mater. Des. 2023, 227, 111751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbani, K.; Hardan, L.; Eid, R.; Skienhe, H.; Alharbi, N. Fracture resistance of three-unit fixed dental prostheses fabricated with milled and 3D-printed composite-based materials. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 985–990. [Google Scholar]

- Alqurashi, H.; Khurshid, Z.; Syed, A.U.Y.; Habib, S.R.; Rokaya, D.; Zafar, M.S. Polyetherketoneketone (PEKK): An Emerging Biomaterial for Oral Implants and Dental Prostheses. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 28, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, M.; Li, M.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Y. Comprehensive Review of Polyetheretherketone Use in Dentistry. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2025, 69, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; McGrath, J. Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; Matyjaszewski, K., Möller, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 377–430. [Google Scholar]

- Onodera, K.; Sato, T.; Nomoto, S.; Miho, O.; Yotsuya, M. Effect of Connector Design on Fracture Resistance of Zirconia All-Ceramic Fixed Partial Dentures. Bull. Tokyo Dent. Coll. 2011, 52, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadon, O.; Wood, D.; Patrick, D.; Pollington, S. Fatigue Behavior and Damage Modes of High-Performance Polyetherketoneketone (PEKK) Bilayered Crowns. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 110, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Suárez, C.; Castillo-Oyagüe, R.; Rodríguez-Alonso, V.; Lynch, C.D.; Suárez-García, M.J. Fracture Load of Metal–Ceramic, Monolithic, and Bi-Layered Zirconia-Based Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses after Thermo-Mechanical Cycling. J. Dent. 2018, 73, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, F.J.T. Maximising the Fracture Resistance of Dentine-Bonded All-Ceramic Crowns. J. Dent. 1999, 27, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechteler, C.; Kühl, H.; Girmscheid, R. Morphology and structure characterization of ceramic granules. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 4232–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchert, D.; Moreno, R.; Ghadiri, M.; Litster, J. Effect of granule morphology on breakage behaviour during compression. Powder Technol. 2004, 143, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Hurley, R.C.; Graham-Brady, L. Fragmentation and granular transition of ceramics for high rate loading. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 3062–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.M. (Ed.) High-Performance Polymers for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Paszkiewicz, S.; Lesiak, P.; Walkowiak, K.; Irska, I.; Miądlicki, K.; Królikowski, M.; Piesowicz, E.; Figiel, P. The Mechanical, Thermal, and Biological Properties of Materials Intended for Dental Implants: A Comparison of Three Types of Poly(Aryl-Ether-Ketones) (PEEK and PEKK). Polymers 2023, 15, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloo, L.M.; Toshniwal, S.H.; Reche, A.; Paul, P.; Wanjari, M.B. A Sneak Peek Toward Polyaryletherketone (PAEK) Polymer: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano Moncayo, A.M.; Peñate, L.; Arregui, M.; Giner-Tarrida, L.; Cedeño, R. State of the art of different zirconia materials and their indications according to evidence-based clinical performance: A narrative review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, C.D. Assessing flexural strength degradation of new cubic-containing zirconia materials. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajaj, T.; Lile, I.E.; Veja, I.; Titihazan, F.; Rominu, M.; Negruțiu, M.L.; Sinescu, C.; Novac, A.C.; Talpos Niculescu, S.; Zaharia, C. Influence of Pontic Length on the Structural Integrity of Zirconia Fixed Partial Dentures (FPDs). J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, S.S.; de Rijk, W.G. The Fracture Resistance of All-Ceramic Crowns on Supporting Structures with Different Elastic Moduli. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1993, 6, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadeqi, H.A.; Baig, M.R.; Al-Shammari, M. Evaluation of Marginal/Internal Fit and Fracture Load of Monolithic Zirconia and Zirconia Lithium Silicate (ZLS) CAD/CAM Crown Systems. Materials 2021, 14, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, M.H. Mechanical Properties and Biocompatibility of Various Cobalt–Chromium Alloys for Dental Prostheses. Materials 2023, 16, 3746. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.S.; Kim, S.K.; Jang, J.H.; Park, J.H. Mechanical Behavior of 316L Stainless Steel Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2019, 12, 3050. [Google Scholar]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Beuer, F.; Wimmer, T.; Jahn, D.; Sener, B.; Roos, M.; Schmidlin, P.R. Polyetheretherketone—A Suitable Material for Fixed Dental Prostheses? J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2013, 101, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoidis, P.; Bakiri, E.; Papathanasiou, I.; Zappi, A. Modified PEEK as an Alternative Crown Framework Material for Weak Abutment Teeth: A Case Report. Gen. Dent. 2017, 65, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Priya, D.J.; Lambodharan, R.; Balakrishnan, S.; Muthukumar, R.; Selvaraj, S.; Ramalingam, S. Effect of Aging and Thermocycling on Flexural Strength of PEEK as a Provisional Restoration for Full Mouth Rehabilitation—An In Vitro Study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2023, 34, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Huang, M.; Dang, P.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X. PEEK in Fixed Dental Prostheses: Application and Adhesion Improvement. Polymers 2022, 14, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Connector | Height (mm) | Width (mm) | Area (mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesial | 4.728 | 4.211 | 19.909 |

| Central | 5.632 | 4.196 | 23.631 |

| Distal | 4.460 | 3.768 | 16.805 |

| Materials | Manufacturers | Composition | Flexural Strength [MPa] According to Manufacturer | Material Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK | Dental Direkt GmbH Industriezentrum 106–108, 32139 Spenge, Germany | Polyetheretherketone ≥ 99.99 [wt%], further additives < 0.01 [wt%] | ≥155 | Lot no. 01060020 registered trademark of Cendres+Métaux Holding SA, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland. |

| PEKK | Cendres+Métaux SA Rue de Boujean 122 CH-250, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland | Polyetherketoneketone titanium dioxide | 200 | Lot no. 01060020 registered trademark of Cendres+Métaux Holding SA, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland. |

| 3Y Zirconia | Dental Direkt GmbH Industriezentrum 106–108, 32139 Spenge, Germany | Zr + Hf + ≥ 99.0 [weight %], < 8 [weight %], < 0.15 [weight %], other oxides < 1 [weight %] | 1200 ± 150 | Lot no. 02_20221212 Dental Direkt GmbH Industriezentrum 106–108, 32139 Spenge, Germany, Tel.: +49-5225-863190 |

| 4Y Zirconia | Dental Direkt GmbH Industriezentrum 106–108, 32139 Spenge, Germany | Zr + Hf + ≥ 99.0 [weight %], < 8 [weight %], < 0.15 [weight %], other oxides < 1 [weight %] | 700 | Lot no. 02_20221212 Dental Direkt GmbH Industriezentrum 106–108, 32139 Spenge, Germany, Tel.: +49-5225-863190 |

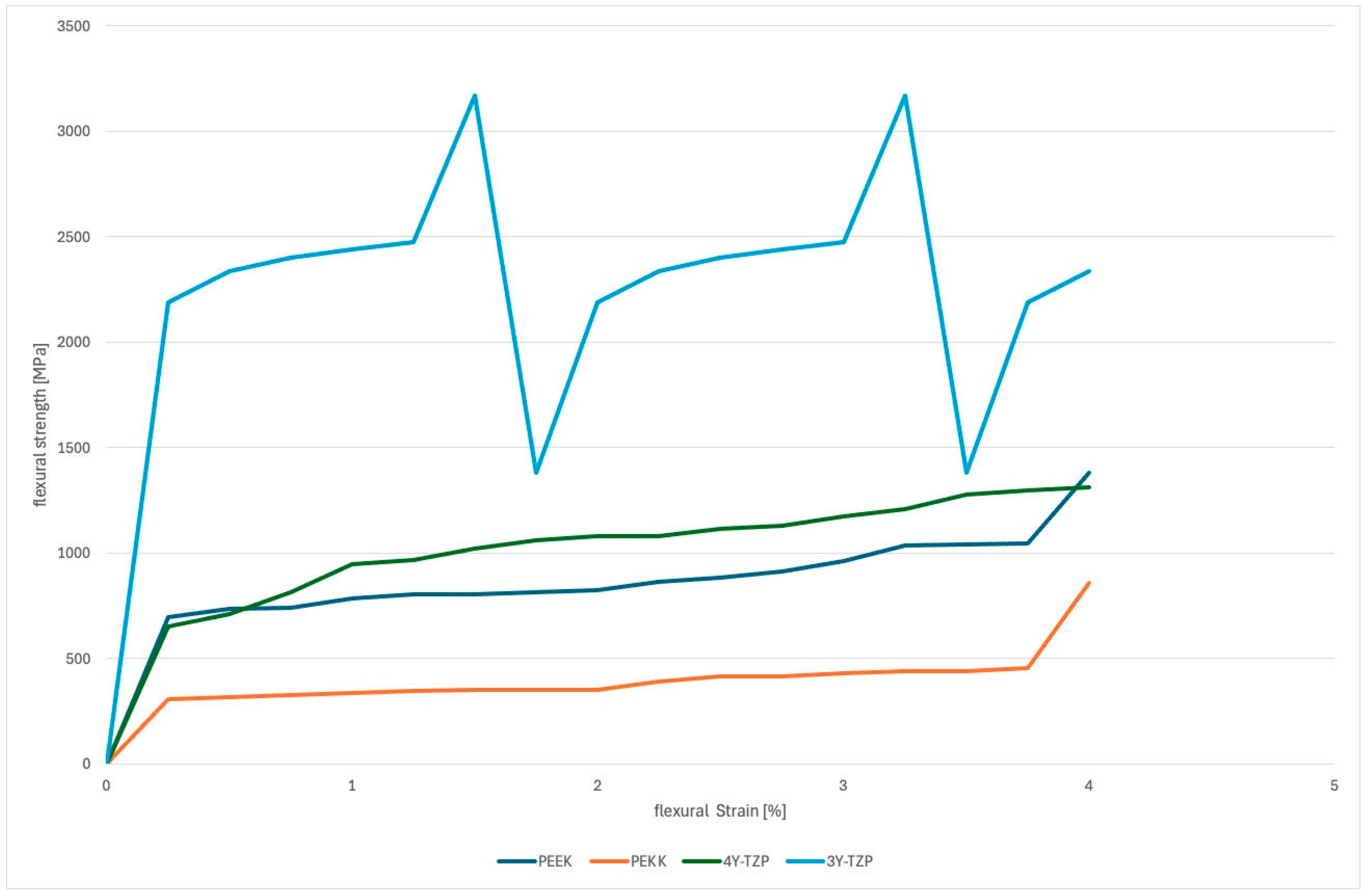

| Material | N | Fracture Load Mean (N) * | SD | MIN | MAX | Flexural Modulus ** | SD | MIN | MAX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK | 17 | 883.21 a | 172.24 | 687.01 | 1380.83 | 116.79 a | 14.87 | 77.94 | 139.41 |

| PEKK | 17 | 402.01 a | 127.98 | 298.64 | 856.86 | 121.87 a | 19.66 | 94.78 | 160.31 |

| 3Y Zirconia | 17 | 2403 a | 497.15 | 1383.02 | 3167.33 | 694.07 a | 106.11 | 508.11 | 890.50 |

| 4Y Zirconia | 17 | 1034.28 b | 221.55 | 650.35 | 1383.02 | 512.02 a | 96.11 | 408.11 | 790.50 |

| Material | Maximum Deformation (mm) | Maximum Equivalent Stress (MPa) | Strain Energy (mJ) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEKK | 1.1252 | 239.73 | 0.09821 | Slightly more brittle than PEEK. |

| PEEK | 1.1231 | 314.72 | 0.18463 | High flexibility, moderate stress. |

| Zirconia | 2.9251 | 5083.6 | 2.9781 | Exceptional stress resistance but brittle. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bukhary, D.M.; Asiri, H.Y.; Alshali, R.Z.; Babaeer, W.A.; Marghalani, T.Y.; Basunbul, G.I.; Qutub, O.A. Fracture Load of Polyaryletherketone for 4-Unit Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: An In Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120448

Bukhary DM, Asiri HY, Alshali RZ, Babaeer WA, Marghalani TY, Basunbul GI, Qutub OA. Fracture Load of Polyaryletherketone for 4-Unit Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: An In Vitro Study. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120448

Chicago/Turabian StyleBukhary, Dalea M., Hasan Y. Asiri, Ruwaida Z. Alshali, Walaa A. Babaeer, Thamer Y. Marghalani, Ghadeer I. Basunbul, and Osama A. Qutub. 2025. "Fracture Load of Polyaryletherketone for 4-Unit Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: An In Vitro Study" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120448

APA StyleBukhary, D. M., Asiri, H. Y., Alshali, R. Z., Babaeer, W. A., Marghalani, T. Y., Basunbul, G. I., & Qutub, O. A. (2025). Fracture Load of Polyaryletherketone for 4-Unit Posterior Fixed Dental Prostheses: An In Vitro Study. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120448