In Vitro Study Regarding Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts to a 3D-Printed Resin for Denture Bases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Purpose

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Specimen Preparation

3.2. Analysis of the Specimens

3.3. Cell Culture

3.4. Cell Viability Assay

3.5. Griess Assay

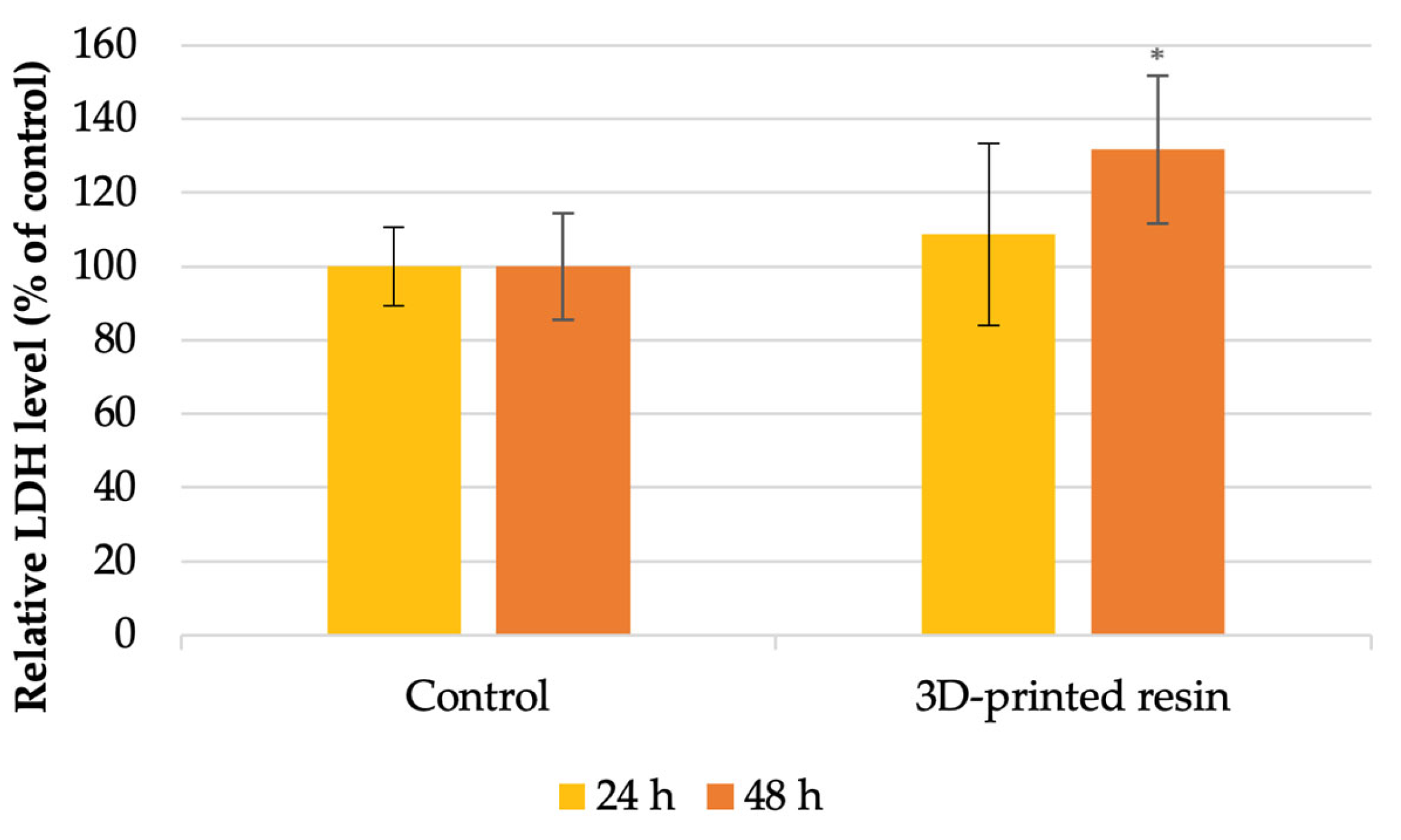

3.6. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay

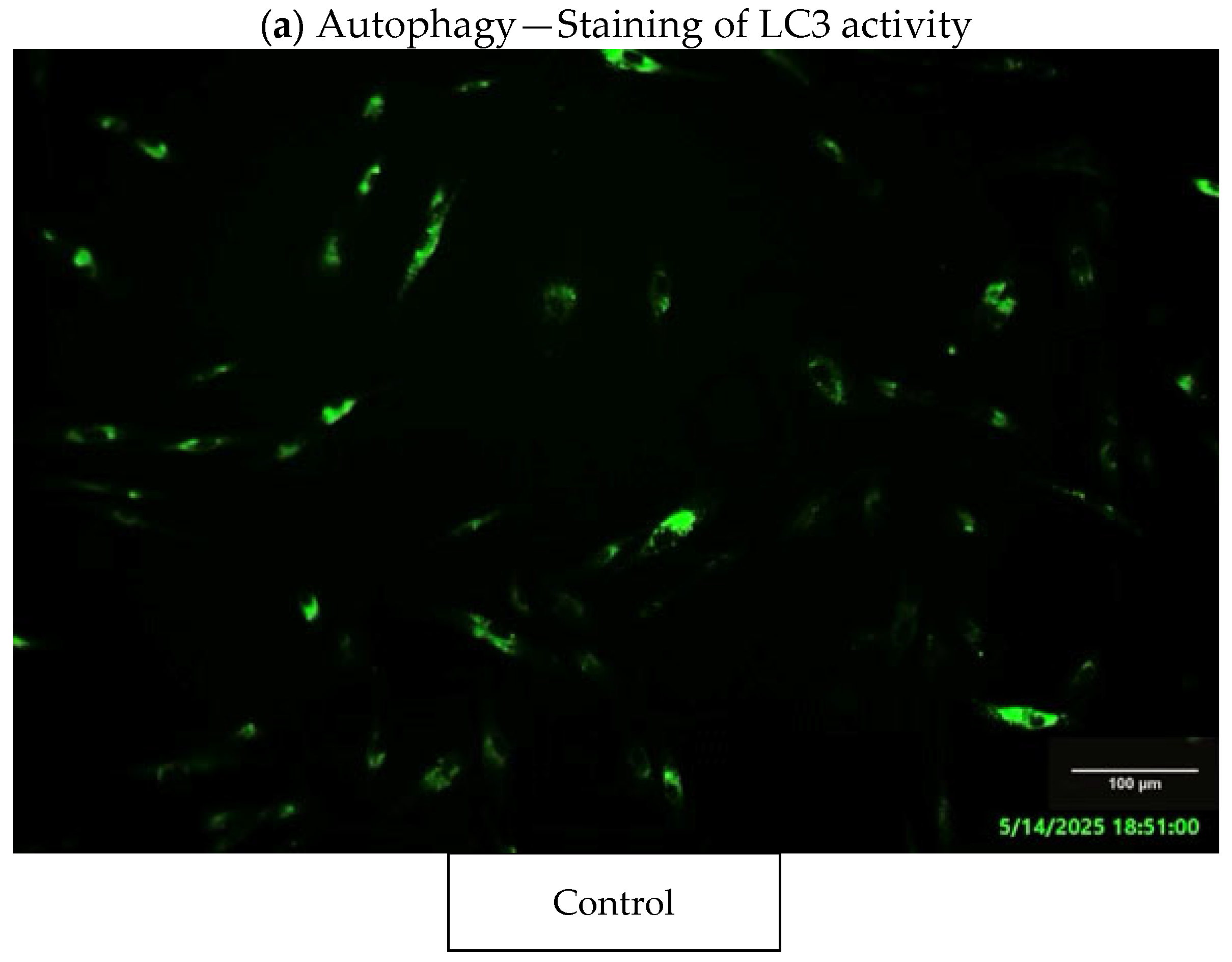

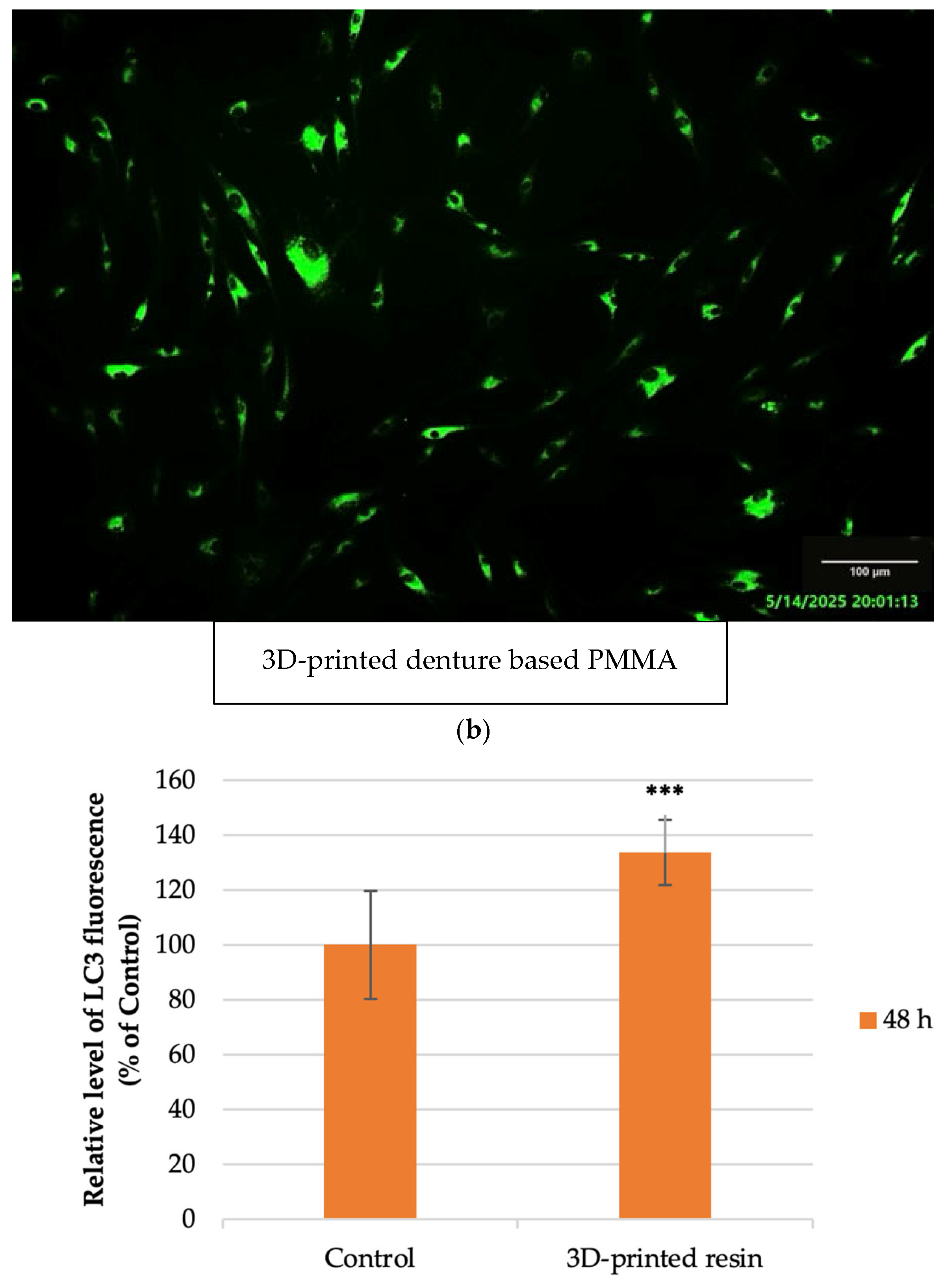

3.7. Fluorescence Staining Assays

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

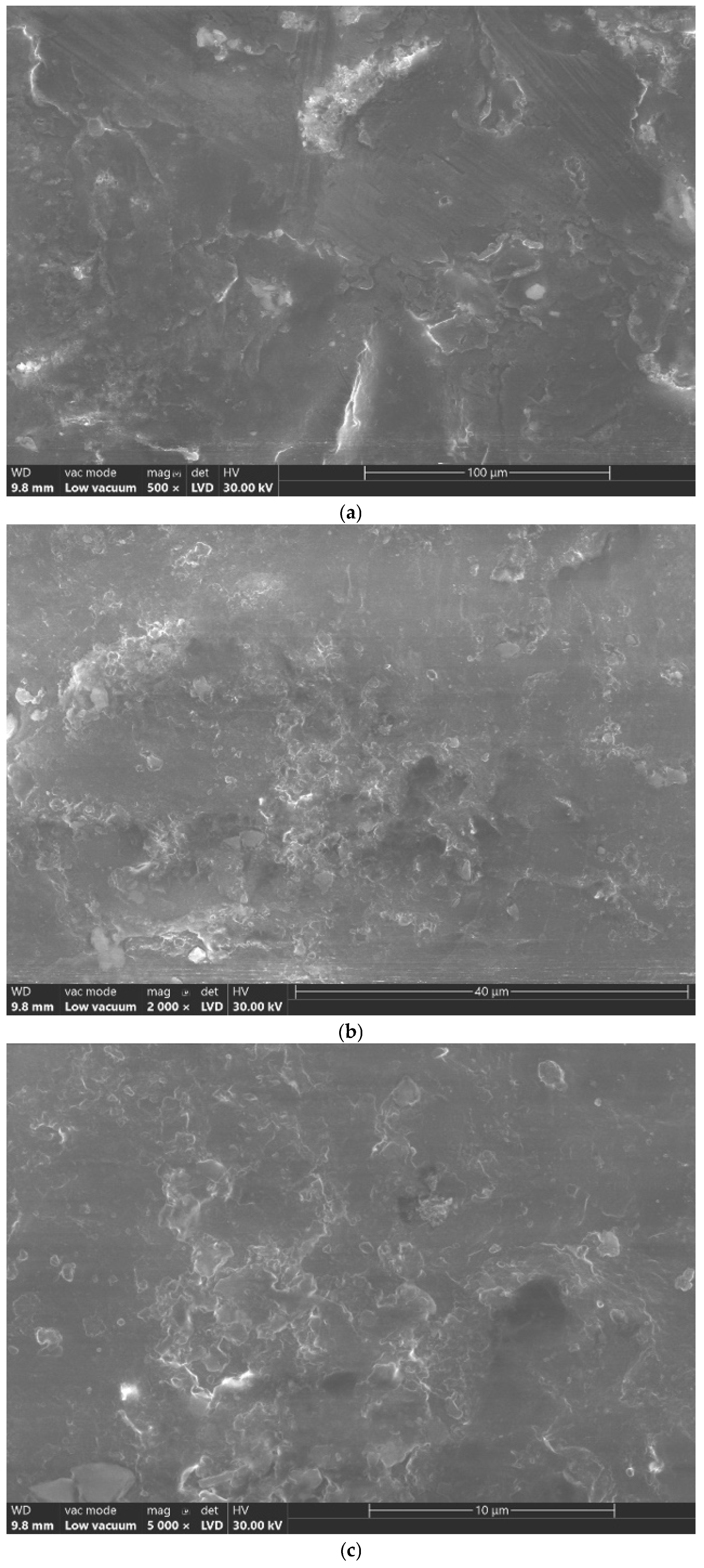

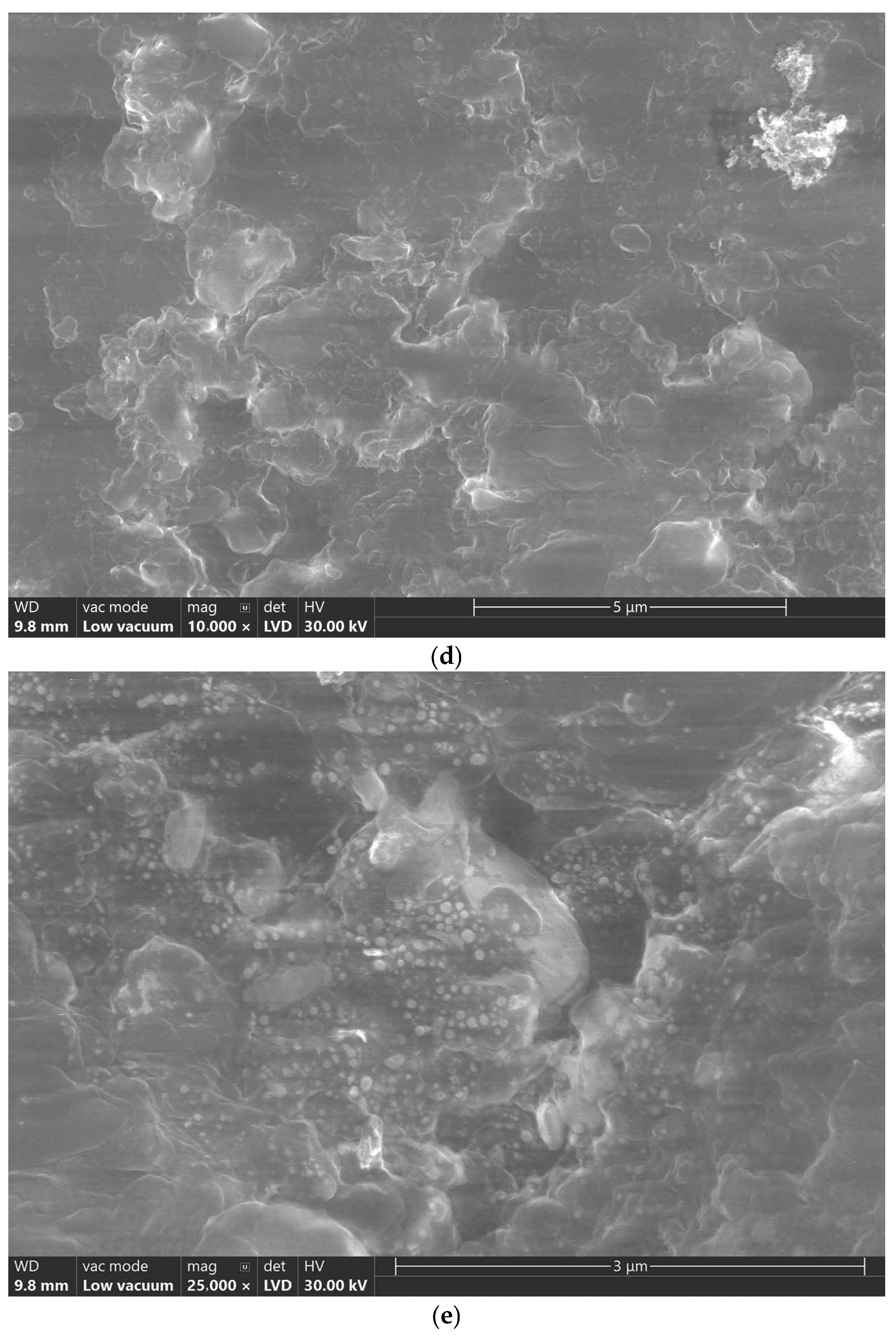

4.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

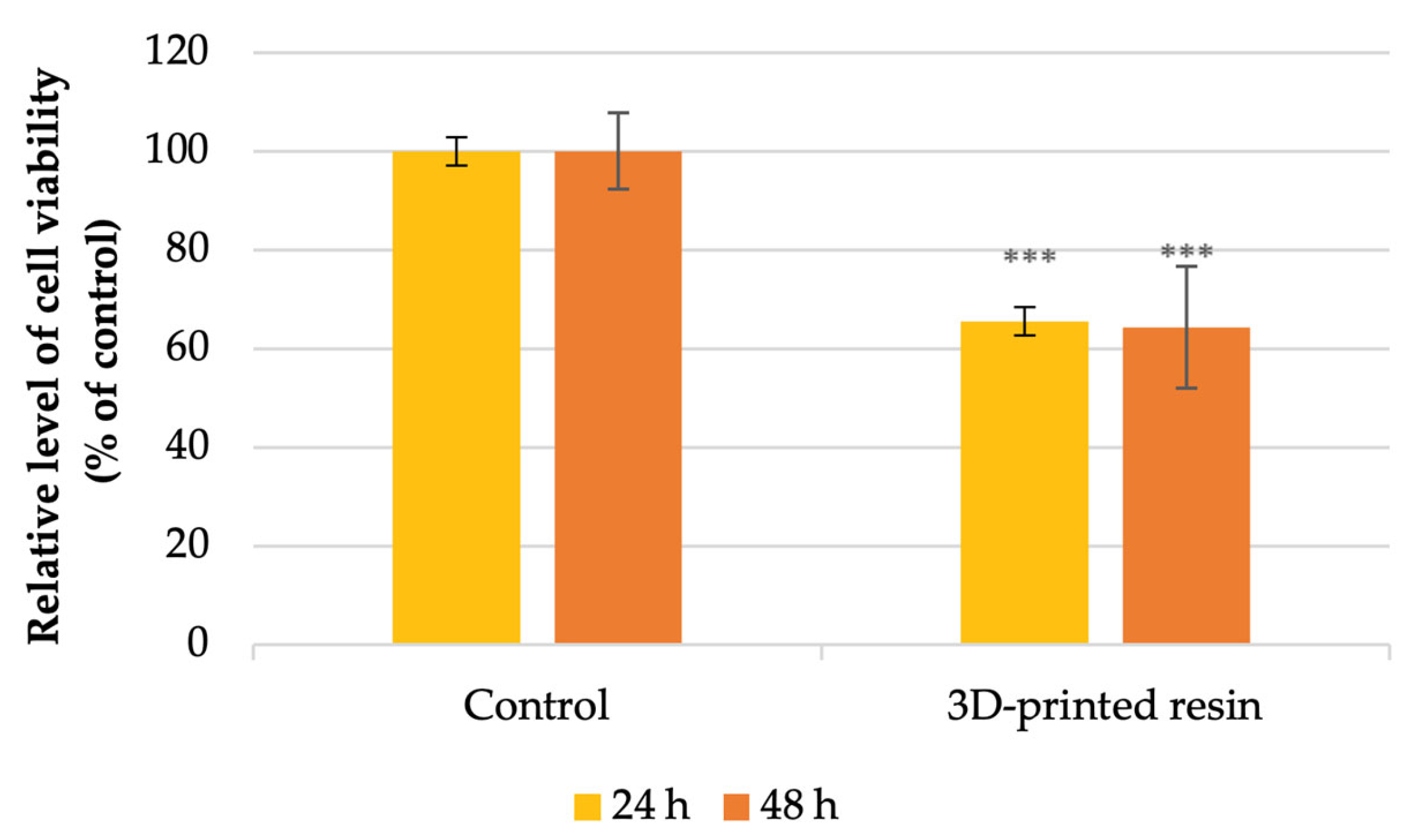

4.2. Cell Viability Analysis

4.3. Autophagy Assessment

5. Discussion

- Poly[oxy(methyl-1,2-ethanediyl)], α,α’-(2,2-dimethyl-1,3-propanediyl)bis[ω-[(1-oxo-2-propenyl)oxy]-] (25–50%)—a difunctional polyether dimethacrylate that provides flexibility and reduces viscosity.

- 7,7,9(7,9,9)-trimethyl-4,13-dioxo-3,14-dioxa-5,12-diazahexadecane-1,16-diylbismethacrylate (25–50%)—a urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) derivative that forms the structural backbone, enhancing hardness and toughness.

- Aliphatic urethane triacrylate (10–25%)—a highly cross-linkable oligomer improving rigidity, scratch resistance, and surface hardness.

- Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (TPO) (1–3%)—a photo-initiator that generates free radicals upon exposure to visible or UV light (≈405 nm), initiating polymerization.

6. Conclusions

- Cell viability: decreased by 35% at 24 h and 36% at 48 h.

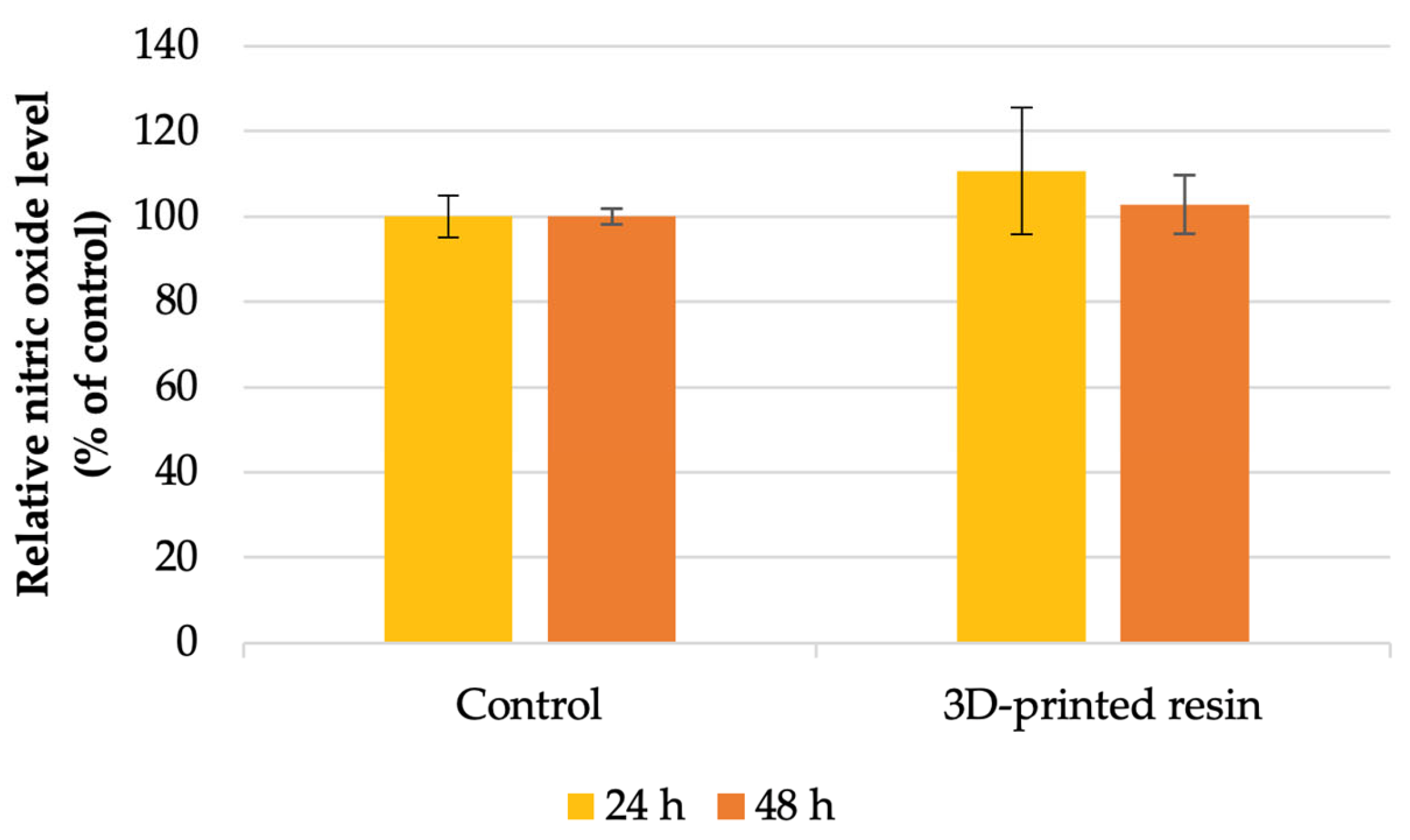

- Nitric oxide production: increased by 10% after 24 h and 2% after 48 h.

- LDH release: increased by 8% at 24 h and 31% at 48 h, indicating membrane damage.

- Autophagy marker (LC3): significantly elevated fluorescence levels in exposed fibroblasts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D-printing | Three-dimensional printing |

| Bis-GMA | Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate |

| CAD-CAM | Computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing |

| CSF | Cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid |

| DLP | Digital light processing |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| HFIB-G | Human fibroblast–gingiva cell line |

| HGF | Human gingival fibroblasts |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| IL-14 | Interleukin-14 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1 alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-33 | Interleukin-33 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 |

| LC3-II | Microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PTMs | Protein post-translational modifications |

| SDS | Safety Data Sheet |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| STL | Standard tessellation language |

| T cells | Thymus-derived lymphocytes |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TPO | Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Wulfman, C.; Bonnet, G.; Carayon, D.; Lance, C.; Fages, M.; Vivard, F.; Daas, M.; Rignon-Bret, C.; Naveau, A.; Millet, C.; et al. Digital removable complete denture: A narrative review. Fr. J. Dent. Med. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, M.; Kumar, M.N.; RaghavendraSwamy, K.; Thippeswamy, H. Flexural strength and impact strength of heat-cured acrylic and 3D printed denture base resins–a comparative in vitro study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2022, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goiato, M.C.; Freitas, E.; dos Santos, D.; de Medeiros, R.; Sonego, M. Acrylic resin cytotoxicity for denture base—Literature review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, J.H.; Giampaolo, E.T.; Vergani, C.E.; Machado, A.L.; Pavarina, A.C.; Carlos, I.Z. Biocompatibility of denture base acrylic resins evaluated in culture of L929 cells: Effect of polymerisation cycle and post-polymerisation treatments. Gerodontology 2007, 24, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, N.G.; Mahajan, A. Comparison of cytotoxicity between 3D printable resins and heat-cure PMMA. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2024, 14, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocan, L.T.; Biru, E.I.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Ghitman, J.; Stefan, A.-R.; Iovu, H.; Ilici, R. Influence of Air-Barrier and Curing Light Distance on Conversion and Micro-Hardness of Dental Polymeric Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Lowery, L.; Gibreel, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L.V. 3D-Printed vs. Heat-Polymerizing and Autopolymerizing Denture Base Acrylic Resins. Materials 2021, 14, 5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsandi, Q.; Ikeda, M.; Arisaka, Y.; Nikaido, T.; Tsuchida, Y.; Sadr, A.; Yui, N.; Tagami, J. Evaluation of Mechanical and Physical Properties of Light and Heat Polymerized UDMA for DLP 3D Printer. Sensors 2021, 21, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-M.; Lai, Y.-L.; Lee, S.-Y. Mechanical Properties, Accuracy, and Cytotoxicity of UV-Polymerized 3D Printing Resins Composed of Bis-EMA, UDMA, and TEGDMA. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupancic Cepic, L.; Gruber, R.; Eder, J.; Vaskovich, T.; Schmid-Schwap, M.; Kundi, M. Digital versus conventional dentures: A prospective, randomized cross-over study on clinical efficiency and patient satisfaction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, T.; Kanazawa, M.; Iwaki, M.; Arakida, T.; Soeda, Y.; Katheng, A.; Otake, R.; Minakuchi, S. Effect of printing direction on the accuracy of 3D-printed dentures using stereolithography technology. Materials 2020, 13, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, F.C.; Yang, T.C.; Wang, T.M.; Lin, L.D. Dimensional changes of complete dentures fabricated by milled and printed techniques: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, M.; Chien, E.C.; Kalberer, N.; Alambiaga Caravaca, A.M.; López Castelleno, A.; Kamnoedboon, P.; Sauro, S.; Özcan, M.; Müller, F.; Wismeijer, D. Analysis of the residual monomer content in milled and 3D-printed removable CAD-CAM complete dentures: An in vitro study. J. Dent. 2022, 120, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Singh, R.D.; Sharma, V.P.; Siddhartha, R.; Chand, P.; Kumar, R. Biocompatibility of polymethylmethacrylate resins used in dentistry. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2012, 100, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, S.; Lombardo, G.; Caponi, S.; Costanzi, E.; Di Michele, A.; Bruscoli, S.; Xhimitiku, I.; Coniglio, M.; Valenti, C.; Mattarelli, M.; et al. Bio-mechanical characterization of a CAD/CAM PMMA resin for digital removable prostheses. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e118–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices-Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/36406.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Revilla-León, M.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies used for processing polymers: Current status and potential application in prosthetic dentistry. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocan, L.T.; Ghitman, J.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Iovu, H. Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Based Blanks for Machined Dental Restorations. Materials 2021, 14, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imre, M.; Șaramet, V.; Ciocan, L.T.; Vasilescu, V.-G.; Biru, E.I.; Ghitman, J.; Pantea, M.; Ripszky, A.; Celebidache, A.L.; Iovu, H. Influence of the Processing Method on the Nano-Mechanical Properties and Porosity of Dental Acrylic Resins Fabricated by Heat-Curing, 3D Printing and Milling Techniques. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anadioti, E.; Musharbash, L.; Blatz, M.B.; Papavasiliou, G.; Kamposiora, P. 3D printed complete removable dental prostheses: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emera, R.M.K.; Shady, M.; Alnajih, M.A. Comparison of retention and denture base adaptation between conventional and 3D-printed complete dentures. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospects 2022, 16, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.; Gjengedal, H.; Cattani-Lorente, M.; Moussa, M.; Durual, S.; Schimmel, M.; Müller, F. CAD/CAM milled complete removable dental prostheses: An in vitro evaluation of biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and surface roughness. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.-N.; Oh, K.C.; Lee, S.J.; Han, J.-S.; Yoon, H.-I. Tissue surface adaptation of CAD-CAM maxillary and mandibular complete denture bases manufactured by digital light processing: A clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Fu, B.; et al. Expert consensus on digital restoration of complete dentures. Int J Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahya Karaca, S.; Akca, K. Comparison of conventional and digital impression approaches for edentulous maxilla: Clinical study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnabi, M.H.; Swelem, A.A. 3D-Printed Complete Dentures: A Review of Clinical and Patient-Based Outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e69698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.; Kamnoedboon, P.; McKenna, G.; Angst, L.; Schimmel, M.; Özcan, M.; Müller, F. CAD-CAM removable complete dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trueness of fit, biocompatibility, mechanical properties, surface characteristics, color stability, time-cost analysis, clinical and patient-reported outcomes. J. Dent. 2021, 113, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, J.-J.; Yang, T.-S.; Lee, W.-F.; Chen, H.; Chang, H.-M. Mechanical properties and biocompatibility of urethane acrylate-Based 3D-printed denture base resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentamid FotoDent® Denture 385/405 nm. Available online: https://dentamidshop.dreve.de/dentamiden/fotodentr-denture-385-nm-4815.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Kollmuss, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Schwendicke, F.; Wuersching, S.N. In Vitro Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts and Oral Mucosal Keratinocytes to 3D Printed Oral Devices. Polymers 2024, 16, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, R.; Suma, K.; JayaKrishnaKumar, S.; Rajkumar, G.; Kumar, S.A.; Geethakumari, R. Chemical Characterization of Denture Base Resin with a Novel Cycloaliphatic Monomer. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 940–946. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthi, D.; Karthigeyan, S.; Ali, S.A.; Rajajayam, S.; Gajendran, R.; Rajendran, M. Evaluation of the In-Vitro Cytotoxicity of Heat Cure Denture Base Resin Modified with Recycled PMMA-Based Denture Base Resin. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14 (Suppl. S1), S719–S725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-T.; Go, H.-B.; Yu, J.-H.; Yang, S.-Y.; Kim, K.-M.; Choi, S.-H.; Kwon, J.-S. Cytotoxicity, Colour Stability and Dimensional Accuracy of 3D Printing Resin with Three Different Photoinitiators. Polymers 2022, 14, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakırbay Tanış, M.; Akay, C.; Sevim, H. Cytotoxicity of Long-Term Denture Base Materials. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2018, 41, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuchulska, B.; Dimitrova, M.; Vlahova, A.; Hristov, I.; Tomova, Z.; Kazakova, R. Comparative Analysis of the Mechanical Properties and Biocompatibility between CAD/CAM and Conventional Polymers Applied in Prosthetic Dentistry. Polymers 2024, 16, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Rocha, L.; Ribeiro-Goncalves, L.; Henriques, B.; Ozcan, M.; Tiritan, M.E.; Souza, J.C.M. An integrative review on the toxicity of Bisphenol A (BPA) released from resin composites used in dentistry. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Farid, D.A.; Zahari, N.A.H.; Said, Z.; Ghazali, M.I.M.; Hao-Ern, L.; Mohamad Zol, S.; Aldhuwayhi, S.; Alauddin, M.S. Modification of Polymer Based Dentures on Biological Properties: Current Update, Status, and Findings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertelak-Makała, K.; Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Bociong, K.; Śliwińska, A. Considerations about Cytotoxicity of Resin-Based Composite Dental Materials: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.S.; da Cruz, M.B.; Marques, J.F.; Roque, J.C.; Martins, J.P.; Malheiro, R.C.; da Mata, A.D. Cellular responses to 3D printed dental resins produced using a manufacturer recommended printer versus a third party printer. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2024, 16, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, R.N. Mechanisms of cytokine production by fibroblasts—Implications for normal connective tissue homeostasis and pathological conditions. Folia Microbiol. 1995, 40, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornatowski, W.; Lu, Q.; Yegambaram, M.; Garcia, A.E.; Zemskov, E.A.; Maltepe, E.; Fineman, J.R.; Wang, T.; Black, S.M. Complex Interplay between Autophagy and Oxidative Stress in the Development of Pulmonary Disease. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, G.; Orsini, G.; Salvatore, V.; Focaroli, S.; Mazzotti, M.C.; Ruggeri, A.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M.; Falconi, M. HEMA but Not TEGDMA Induces Autophagy in Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, L.; Tian, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, C.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Nitric oxide inhibits autophagy and promotes apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, M.; Hirata, N.; Tanaka, T.; Suizu, F.; Nakajima, H.; Chiorini, J.A. Autophagy as a modulator of cell death machinery. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Levine, B.; Kroemer, G. Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell 2014, 159, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Gironés, J.; López-García, S.; Pecci-Lloret, M.R.; Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Rodríguez Lozano, F.J.; García-Bernal, D. In vitro biocompatibility testing of 3D printing and conventional resins for occlusal devices. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Mariño, G.; Levine, B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramet, V.; Stan, M.S.; Ripszky Totan, A.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Voicu-Balasea, B.; Enasescu, D.S.; Rus-Hrincu, F.; Imre, M. Analysis of Gingival Fibroblasts Behaviour in the Presence of 3D-Printed versus Milled Methacrylate-Based Dental Resins—Do We Have a Winner? J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea-Maier, R.T.; Plantinga, T.S.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Smit, J.W.; Netea, M.G. Modulation of inflammation by autophagy: Consequences for human disease. Autophagy 2016, 12, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, C.; Rizza, S.; Maiani, E.; Piredda, L.; Filomeni, G.; Cecconi, F. To eat, or NOt to eat: S-nitrosylation signaling in autophagy. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3857–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Li, Y.; Lee, M.; Andrikopoulos, N.; Lin, S.; Chen, C.; Leong, D.T.; Ding, F.; Song, Y.; Ke, P.C. Anionic nanoplastic exposure induces endothelial leakiness. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.; Luo, J.; Qu, C.; Guo, P.; Yi, W.; Yang, J.; Yan, Y.; Guan, H.; Zhou, P.; Huang, R. Predictive metabolomic signatures for safety assessment of three plastic nanoparticles using intestinal organoids. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dinescu, M.; Ciocan, L.T.; Țâncu, A.M.C.; Vasilescu, V.G.; Voicu-Balasea, B.; Rus, F.; Ripszky, A.; Pițuru, S.-M.; Imre, M. In Vitro Study Regarding Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts to a 3D-Printed Resin for Denture Bases. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120442

Dinescu M, Ciocan LT, Țâncu AMC, Vasilescu VG, Voicu-Balasea B, Rus F, Ripszky A, Pițuru S-M, Imre M. In Vitro Study Regarding Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts to a 3D-Printed Resin for Denture Bases. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120442

Chicago/Turabian StyleDinescu, Miruna, Lucian Toma Ciocan, Ana Maria Cristina Țâncu, Vlad Gabriel Vasilescu, Bianca Voicu-Balasea, Florentina Rus, Alexandra Ripszky, Silviu-Mirel Pițuru, and Marina Imre. 2025. "In Vitro Study Regarding Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts to a 3D-Printed Resin for Denture Bases" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120442

APA StyleDinescu, M., Ciocan, L. T., Țâncu, A. M. C., Vasilescu, V. G., Voicu-Balasea, B., Rus, F., Ripszky, A., Pițuru, S.-M., & Imre, M. (2025). In Vitro Study Regarding Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Response of Gingival Fibroblasts to a 3D-Printed Resin for Denture Bases. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120442