The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance in the Academic Performance of University Students: A Structural Equation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.2. Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance: Key Factors in Academic Success

1.3. Burnout and Academic Engagement: Two Sides of the Same Coin

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Design, and Procedure

2.2. Measures

- Sociodemographic data. Participants provided information on age, gender, academic year, and degree program through a brief questionnaire.

- The Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Fernández-Berrocal et al. 2004; validated in Chile by Espinoza et al. 2015), developed by Salovey et al. (1995), was used to assess EI. This instrument consists of 24 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often) and evaluates three dimensions: attention to feelings, emotional clarity, and emotional repair. Each dimension is measured by eight items. Higher scores indicate greater perceived EI. In the present study, we used a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. The subscales also showed high reliability: attention (α = 0.91), clarity (α = 0.92), and repair (α = 0.90).

- The Frustration Discomfort Scale (FDS; Harrington 2005b; validated in Chile by Ruiz-Ortega et al. 2023) was used to measure FI. The scale includes 28 items, divided into four subscales: discomfort intolerance, entitlement, emotional intolerance, and achievement. Responses are given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). Higher scores reflect greater intolerance to frustration. The total scale showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 in this sample (discomfort intolerance: 0.85; entitlement: 0.86; emotional intolerance: 0.87; achievement: 0.82).

- The Maslach Burnout Inventory Student Survey (MBI-SS; Maslach et al. 1996; validated in Chile by Pérez et al. 2012). This 22-item instrument uses a 7-point Likert scale (0 = never, 6 = always) and measures three dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and academic efficacy. Higher scores in exhaustion and cynicism, and lower scores in efficacy, indicate greater burnout. The total scale showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 in this study (exhaustion: 0.91; cynicism: 0.72; efficacy: 0.79).

- The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale Students (UWES-S-9; Schaufeli et al. 2006) was used to assess academic engagement. This scale consists of 9 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = never, 6 = always), measuring vigor, dedication, and absorption. Higher scores indicate higher engagement. The total scale showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94 in this study (Vigor: 0.86; Absorption: 0.89; Dedication: 0.88).

- Academic performance. GPA from the previous semester was used as the indicator of academic achievement, obtained from official university records, using Chilean standard grading (1 to 7) untransformed for transparency. The GPA represents the mean of all final course grades from the prior semester, reflective of each program’s assessment system, and includes a range of evaluation types (e.g., written and oral exams, assignments, practical work, and participation).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Model Fit Assessment

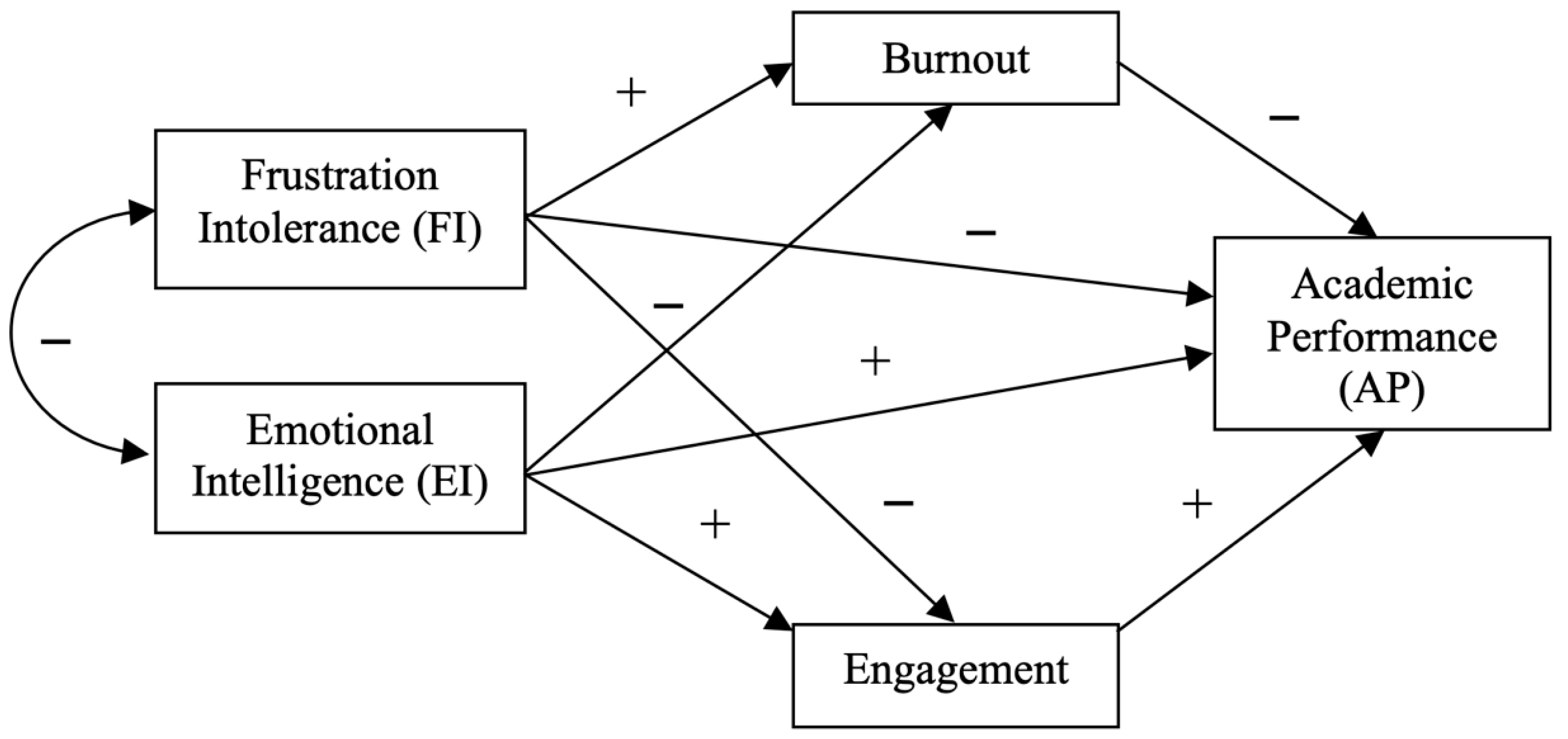

3.4. The Structural Equation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Elaboration

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakare, J. D., A. O. Owolabi, A. A. Tijani, and O. R. Adesope. 2019. Investigation of burnout syndrome among electrical and building technology undergraduate students in Nigeria. Medicine 98: e17954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, Ana Sanz-Vergel, and Alfredo Rodríguez-Muñoz. 2023. La Teoría de las Demandas y Recursos Laborales: Nuevos desarrollos en la última década. Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology 39: 157–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Dan, Faridah Mydin, Shahlan Surat, Yanhong Lyu, Dongsheng Pan, and Yahua Cheng. 2024. Challenge-hindrance stressors and academic engagement among medical postgraduates in China: A moderated mediation model. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 17: 1115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, Monique, and Reinhard Pekrun. 2015. Emotions and emotion regulation in academic settings. In Handbook of Educational Psychology. Edited by Lyn Corno and Eric M. Anderman. New York: Routledge, pp. 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresó, Edgar, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Marisa Salanova. 2011. Can a self-efficacy-based intervention decrease burnout, increase engagement, and enhance performance? A quasi-experimental study. Higher Education 61: 339–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Michael W., and Robert Cudeck. 1992. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research 21: 230–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, Caterina, Luana Sorrenti, Sebastiano Costa, Mary Ellen Toffle, and Pina Filippello. 2021. The relationship between school-basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration, academic engagement and academic achievement. School Psychology International 42: 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, Francisco, C. Pichardo, A. Justicia-Arráez, M. Romero-López, and A. B. G. Berbén. 2024. Identifying higher education students’ profiles of academic engagement and burnout and analysing their predictors and outcomes. European Journal of Psychology of Education 39: 4181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. 2022. Defining, Writing and Applying Learning Outcomes: A European Handbook, 2nd ed. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hongxia, and Morning Hon Zhang. 2022. The relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and university students’ academic engagement: The mediating effect of emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 917578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Floody, Pedro, Bastián Carter-Thuillier, Iris Paola Guzmán-Guzmán, Pedro Latorrre-Román, and Felipe Caamaño-Navarrete. 2020. Low indicators of personal and social development in Chilean schools are associated with unimproved academic performance: A national study. International Journal of Educational Research 104: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Albert. 1962. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, Maritza, Olivia Sanhueza-Alvarado, Noé Ramírez-Elizondo, and Katia Sáez-Carrillo. 2015. Validación de constructo y confiabilidad de la escala de inteligencia emocional en estudiantes de enfermería. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 23: 139–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, Pablo, Natalio Extremera, and Natalia Ramos. 2004. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Reports 94: 751–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzi Behnagh, Reza, and Joseph R. Ferrari. 2022. Exploring 40 years on affective correlates to procrastination: A literature review of situational and dispositional types. Current Psychology 41: 1097–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, Caterina, Simona De Stasio, Carlo Di Chiacchio, Alessandro Pepe, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2017. School burnout, depressive symptoms and engagement: Their combined effect on student achievement. International Journal of Educational Research 84: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Kapil. 2023. Validity and reliability of students’ assessment: Case for recognition as a unified concept of valid reliability. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research 13: 129–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halimi, Florentina, Iqbal AlShammari, and Cristina Navarro. 2020. Emotional intelligence and academic achievement in higher education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 13: 85–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, Eric A., and Ludger Woessmann. 2012. Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation. Journal of Economic Growth 17: 267–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Neil. 2005a. It’s too difficult! Frustration intolerance beliefs and procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences 39: 873–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Neil. 2005b. The frustration discomfort scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 12: 374–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuga, Ioana Alexandra, and Oana Alexandra David. 2024. Emotion regulation and academic burnout among youth: A quantitative meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review 36: 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodics, Balázs, and Éva Szabó. 2023. Student burnout in higher education: A demand-resource model approach. Trends in Psychology 31: 757–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principle and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsou, Ilios, Delphine Nelis, Jacques Grégoire, and Moïra Mikolajczak. 2011. Emotional plasticity: Conditions and effects of improving emotional competence in adulthood. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 827–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, Archana, and Sandhya Gupta. 2015. A study of emotional intelligence and frustration tolerance among adolescents. Advance Research Journal of Social Science 6: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Mengting, Xinyin Chen, Rui Fu, Dan Li, and Junsheng Liu. 2023. Social, academic, and psychological characteristics of peer groups in Chinese children: Same-domain and cross-domain effects on individual development. Developmental Psychology 59: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, Natasha M., and Nyree Pryce. 2022. The role of mindful Self-Care in the relationship between emotional intelligence and burnout in university students. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 156: 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, Carolyn, Yixin Jiang, Luke E. Brown, Kit S. Double, Micaela Bucich, and Amirali Minbashian. 2019. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 146: 150–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, Daniel J., and Thomas Curran. 2021. Does burnout affect academic achievement a meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educational Psychology 33: 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Rebecca, Arlene Egan, Philip Hyland, and Phil Maguire. 2017. Engaging students emotionally: The role of emotional intelligence in predicting cognitive and affective engagement in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development 36: 343–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanchini, Margherita, Andrea G. Allegrini, Michel G. Nivard, Pietro Biroli, Kaili Rimfeld, Rosa Cheesman, Sophie von Stumm, Perline A. Demange, Elsje van Bergen, Andrew D. Grotzinger, and et al. 2024. Genetic associations between non-cognitive skills and academic achievement over development. Nature Human Behaviour 8: 2034–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marôco, João, Hugo Assunção, Heidi Harju-Luukkainen, Su-Wei Lin, Pou-Seong Sit, Kwok-cheung Cheung, Benvindo Maloa, Ivana Stepanović Ilic, Thomas J. Smith, and Juliana A. D. B. Campos. 2020. Predictors of academic efficacy and dropout intention in university students: Can engagement suppress burnout? PLoS ONE 15: e0239816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, Ainhoa, and Camino Ferreira. 2025. Factors influencing the development of emotional intelligence in university students. European Journal of Psychology of Education 40: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, Susan E. Jackson, and Michael P. Leiter. 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. Edited by Richard J. Wood and Carlos P. Zalaquett. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D., and P. Salovey. 1997. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications. Edited by Peter Salovey and David J. Sluyter. New York: Basic Books, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mehler, Miriam, Elisabeth Balint, Maria Gralla, Tim Pößnecker, Michael Gast, Michael Hölzer, Markus Kösters, and Harald Gündel. 2024. Training emotional competencies at the workplace: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology 12: 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, Sergio, Magda Sofia Roberto, Vânia Sofia Carvalho, Eloísa Guerrero-Barona, Natalio Extremera, and Maria José Chambel. 2023. Daily exhaustion and engagement in Portuguese health science students: Exploring the contributions of negative events and emotional intelligence facets. Studies in Higher Education 49: 1120–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miñano, Pablo, and Juan Luis Castejón. 2011. Variables cognitivas y motivacionales en el rendimiento académico en Lengua y Matemáticas: Un modelo estructural. Revista de Psicodidáctica 16: 203–30. [Google Scholar]

- Molero-Jurado, María del Mar, María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, África Martos Martínez, Ana Belén Barragán Martín, María del Mar Simón Márquez, and José Jesús Gázquez Linares. 2021. Emotional intelligence as a mediator in the relationship between academic performance and burnout in high school students. PLoS ONE 16: e0253552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelis, Delphine, Ilios Kotsou, Jordi Quoidbach, Michel Hansenne, Fanny Weytens, Pauline Dupuis, and Moïra Mikolajczak. 2011. Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion 11: 354–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Thomas W. H., and Daniel C. Feldman. 2009. How broadly does education contribute to job performance? Personnel Psychology 61: 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2018. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. Position Paper. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Paloș, Ramona, Laurenţiu P. Maricuţoiu, and Iuliana Costea. 2019. Relations between academic performance, student engagement and student burnout: A cross-lagged analysis of a two-wave study. Studies in Educational Evaluation 60: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Harsha N., and Michelle DiGiacomo. 2013. The relationship of trait emotional intelligence with academic performance: A meta-analytic review. Learning and Individual Differences 28: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Cristhian, Paula Parra, Eduardo Fasce, Liliana Ortiz, Nancy Bastías, and Carolina Bustamante. 2012. Estructura factorial y confiabilidad del inventario de burnout de Maslach en universitarios chilenos. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica 21: 255–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, Lorraine Dacre, and Pamela Qualter. 2012. Improving emotional intelligence and emotional selfefficacy through a teaching intervention for university students. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 306–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potard, Catherine, and Clémence Landais. 2021. Relationships between frustration intolerance beliefs, cognitive emotion regulation strategies and burnout among geriatric nurses and care assistants. Geriatric Nursing 42: 700–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Chris, Taylor Brown, Yang Yap, Karen Hallam, Marcel Takac, Tara Quinlivan, Sophia Xenos, and Leila Karimi. 2024. Emotional intelligence training among the healthcare workforce: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1437035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Privado, J., A. B. García-Berbén, and S. Verdugo-Castro. 2024. Academic performance predictors in university students: A meta-analysis of non-cognitive and cognitive variables. Learning and Individual Differences 112: 102310. [Google Scholar]

- Quílez-Robres, Alberto, Pablo Usán, Raquel Lozano-Blasco, and Carlos Salavera. 2023. Emotional intelligence and academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity 49: 101355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumnikova, O. M., and Y. A. Mezentsev. 2020. Relationship of creativity, emotional and general intelligence with academic achievement of students. Voprosy Psikhologii 2: 119–26. [Google Scholar]

- Recabarren, Romina Evelyn, Claudie Gaillard, Matthias Guillod, and Chantal Martin-Soelch. 2019. Short-term effects of a multidimensional stress prevention program on quality of life, well-being and psychological resources: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-de-Cózar, Salvador, Alba Merino-Cajaraville, and María Rosa Salguero-Pazos. 2023. Academic factors that enhance university student engagement. Behavioral Sciences 13: 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Michelle, Charles Abraham, and Rod Bond. 2012. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 138: 353–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I. T., C. L. Cooper, M. Sarkar, and T. Curran. 2018. Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. BMJ Open 8: e017858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega, Ana M., Nicolás Sánchez Álvarez, and M. Pilar Berrios Martos. 2023. Chilean validation of the frustration discomfort scale: Relation between intolerance to frustration and discomfort and emotional intelligence. Current Psychology 42: 9416–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabagh, Zaynab, Nathan C. Hall, Alenoush Saroyan, and Sarah-Geneviève Trépanier. 2021. Occupational factors and faculty well-being: Investigating the nediating role of need frustration. The Journal of Higher Education 93: 559–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, Marisa, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2004. El engagement de los empleados: Un reto emergente para la dirección de recursos humanos. Estudios Financieros 62: 109–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, Marisa, Wilmar Schaufeli, Isabel Martínez, and Edgar Bresó. 2010. How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study Burnout and Engagement. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 23: 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, Katariina, and Sanna Read. 2017. Study engagement and burnout profiles among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research 7: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, Peter, John D. Mayer, Susan Lee Goldman, Carolyn Turvey, and Tibor P. Palfai. 1995. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, and Health. Edited by James W. Pennebaker. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 125–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, M., and R. Castro. 2016. La inteligencia emocional y el rendimiento académico. In Psicología y Educación: Presente y Futuro. Coordinated with J. L. Castejón Costa. Oviedo: Asociación Científica de Psicología y Educación (ACIPE), pp. 1292–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Arnold B. Bakker, and Marisa Salanova. 2006. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement 66: 701–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Isabel M. Martínez, Alexandra Marques Pinto, Marisa Salanova, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002. Burnout and engagement in university students a cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33: 464–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Song, Zizai Zhang, Ying Wang, Huilan Yue, Zede Wang, and Songling Qian. 2021. The relationship between college teachers’ frustration tolerance and academic performance. Frontier 12: 564484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spedding, Jason, Amy J Hawkes, and Matthew Burgess. 2017. Peer assisted study sessions and student performance: The role of academic engagement, student identity, and statistics self-efficacy. Psychology Learning and Teaching 16: 144–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Radhika. 2024. Gender differences in frustration and ambiguity tolerance during COVID-19 pandemic in India. Current Psychology 43: 22072–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, Jan-Benedict, and Alberto Maydeu-Olivares. 2021. An updated paradigm for evaluating measurement invariance incorporating common method variance and its assessment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 49: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutil-Rodríguez, Elena, Cristina Liébana-Presa, and Elena Fernández-Martínez. 2024. Emotional intelligence, health, and performance in nursing students: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Education 63: 686–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Jing, Jie Mao, Yizhang Jiang, and Ming Gao. 2021. The influence of academic emotions on learning effects: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, Edinaldo, Laura Beaudin, and Jodie-Gaye Hunter. 2017. Re-assessing the impact of academic performance on salary level and growth: A case study. Applied Economics Letters 24: 804–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Christopher L., and Kristie Allen. 2021. Driving engagement: Investigating the influence of emotional intelligence and academic buoyancy on student engagement. Journal of Further and Higher Education 45: 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, Katja, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2015. Cross-lagged associations between study and work engagement dimensions during young adulthood. Journal of Positive Psychology 10: 346–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ruowei, and Arumugam Raman. 2025. Systematic literature review on the effects of blended learning in nursing education. Nurse Education in Practice 82: 104238. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595324003676 (accessed on 17 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yurou, Hui Wang, Shengnan Wang, Stefanie A. Wind, and Christopher Gill. 2024. A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-determination-theory-based interventions in the education context. Learning and Motivation 87: 102015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A., H. W. Stoker, and M. Murray-Ward. 1996. Educational Measurement: Theories and Applications. 3 vols. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Minru, Hua Huang, Yuanshu Fu, and Xudong Zhang. 2023. The effect of anti-frustration ability on academic frustration among Chinese undergraduates: A moderated mediating model. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1033190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Yu Jin, De Pin Cao, Tao Sun, and Li Bin Yang. 2019. The effects of academic adaptability on academic burnout, immersion in learning, and academic performance among Chinese medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education 19: 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yanhua, Jianfeng Chen, and Xin Zhuang. 2025. Self-determination theory and the influence of social support, flow experience, and self-regulated learning on student learning engagement in self-directed e-learning. Frontiers in Psychology 16: 1545980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Linjia, and Yi Jiang. 2023. Patterns of the satisfaction and frustration of psychological needs and their associations with adolescent students’ school affect, burnout, and achievement. Journal of Intelligence 11: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhoc, Karen C. H., Ronnel B. King, Tony S. H. Chung, and Junjun Chen. 2020. Emotionally intelligent students are more engaged and successful: Examining the role of emotional intelligence in higher education. European Journal of Psychology of Education 35: 839–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, Nina, Antun Palanović, Mitja Ružojčić, Eva Boštjančič, Boris Popov, Dragana Jelić, and Zvonimir Galić. 2024. Differential influence of basic psychological needs on burnout and academic achievement in three southeast European countries. International Journal of Psychology 59: 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables/Dimensions | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AP | 5.34 | 0.67 | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. EI/Attention | 1.70 | 0.67 | −.04 | 0.91 | ||||||||||||

| 3. EI/Clarity | 1.67 | 0.67 | .31 *** | .24 *** | 0.92 | |||||||||||

| 4. EI/Repair | 1.78 | 0.69 | .32 *** | .14 *** | .56 *** | 0.90 | ||||||||||

| 5. E/Vigour | 2.35 | 0.76 | .34 *** | .12 *** | .31 *** | .36 *** | 0.86 | |||||||||

| 6. E/Absorption | 2.64 | 0.66 | .27 *** | .15 *** | .25 *** | .29 *** | .63 *** | 0.89 | ||||||||

| 7. E/Dedication | 2.51 | 0.69 | .32 *** | .10 * | .29 *** | .33 *** | .72 *** | .72 *** | 0.88 | |||||||

| 8. B/Emotional exhaustion | 2.40 | 0.77 | −.36 *** | .11 ** | −.32 *** | −.34 *** | -.28 *** | −.24 *** | −.28 *** | 0.91 | ||||||

| 9. B/Cynicism | 2.02 | 0.87 | −.26 *** | .06 | −.20 *** | −.23 *** | −.21 *** | −.24 *** | −.22 *** | .51 *** | 0.72 | |||||

| 10. B/Academic self-efficacy | 2.21 | 0.83 | −.29 *** | .02 | −.33 *** | −.38 *** | −.38 *** | −.36 *** | −.37 *** | .58 *** | .59 *** | 0.79 | ||||

| 11. FI/Discomfort intolerance | 1.89 | 0.62 | −.29 *** | .14 *** | −.24 *** | −.28 *** | −.24 *** | −.27 *** | −.27 *** | .37 *** | .29 *** | .29 *** | 0.85 | |||

| 12. FI/Entitlement | 1.94 | 0.65 | −.25 *** | .12 *** | −.25 *** | −.25 *** | −.19 *** | −.22 *** | −.22 *** | .33 *** | .27 *** | .27 *** | .64 *** | 0.86 | ||

| 13. FI/Emotional intolerance | 2.01 | 0.66 | −.28 *** | .16 *** | −.30 *** | −.27 *** | −.23 *** | −.26 *** | −.24 *** | .36 *** | .28 *** | .25 *** | .65 *** | .63 *** | 0.87 | |

| 14. FI/Achievement | 2.11 | 0.62 | −.23 *** | .23 *** | −.19 *** | −.21 *** | −.13 ** | −.12 ** | .08* | .31 *** | .20 *** | .19 *** | .60 *** | .60 *** | .66 | 0.82 |

| Construct Criteria | Measures of Goodness of Fit (SEM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c2/df (<5) | CFI (≈1) | TLI (≈1) | RMSEA (≈0) | SRMR (≈0) | |

| 2.93 | 0.969 | 0.958 | 0.055 | 0.044 | |

| β 95% Confidence Intervals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variable | Response Variable | Estimate | S.E. | β | Lower | Upper | z | p | |

| EI | → | E | 0.548 | 0.0671 | 0.472 | 0.379 | 0.566 | 8.16 | <.001 |

| EI | → | B | 0.539 | 0.0738 | −0.472 | −0.580 | −0.364 | −7.31 | <.001 |

| EI | → | AP | 0.266 | 0.0920 | 0.209 | 0.072 | 0.346 | 2.89 | .004 |

| FI | → | B | 0.333 | 0.0670 | 0.276 | 0.170 | 0.038 | 4.98 | <.001 |

| FI | → | E | −0.149 | 0.0574 | −0.121 | −0.211 | −0.031 | −2.59 | .010 |

| FI | → | AP | −0.166 | 0.0658 | −0.123 | −0.217 | −0.030 | −2.53 | .012 |

| E | → | AP | 0.168 | 0.0510 | 0.154 | 0.063 | 0.255 | 3.31 | <.001 |

| B | → | AP | −0.174 | 0.0659 | −0.157 | −0.270 | −0.043 | −2.65 | .008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Ortega, A.M.; Berrios-Martos, M.P. The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance in the Academic Performance of University Students: A Structural Equation Model. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13080101

Ruiz-Ortega AM, Berrios-Martos MP. The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance in the Academic Performance of University Students: A Structural Equation Model. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(8):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13080101

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Ortega, Ana María, and María Pilar Berrios-Martos. 2025. "The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance in the Academic Performance of University Students: A Structural Equation Model" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 8: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13080101

APA StyleRuiz-Ortega, A. M., & Berrios-Martos, M. P. (2025). The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Frustration Intolerance in the Academic Performance of University Students: A Structural Equation Model. Journal of Intelligence, 13(8), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13080101