Academic Performance and Resilience in Secondary Education Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

- The Identity–Self-Esteem Dimension (ISD) refers to internal strengths and more structural aspects of personality (personal identity, self-image, and self-assessment). It is composed of items 1 to 9 (for example, “I am a person who loves myself”).

- The Networks–Models Dimension (NMD) refers to the perception of support, emotional networks, social networks, orientation, and perception of goals. It is composed of items 10 to 18 (for example, “I have a family that supports me”).

- The Learning-Generativity Dimension (LGD) refers to the possibilities of expression, seeking help, facing difficulties, and learning capacity, among others. It is composed of items 19 to 27 (for example, “I can talk about my emotions with others”).

- The Internal Resources Dimension (IRD) refers to the resources and conditions born from the subject in the construction of the response. It is composed of items 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 16, 17, 18, 20, 26, and 27 (for example, “I am optimistic about the future”).

- The External Resources Dimension (ERD) refers to interactional aspects with the environment that intervene in the construction of resilient behaviour. It is composed of items 4, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 25 (for example, “I feel safe in the environment in which I live”).

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

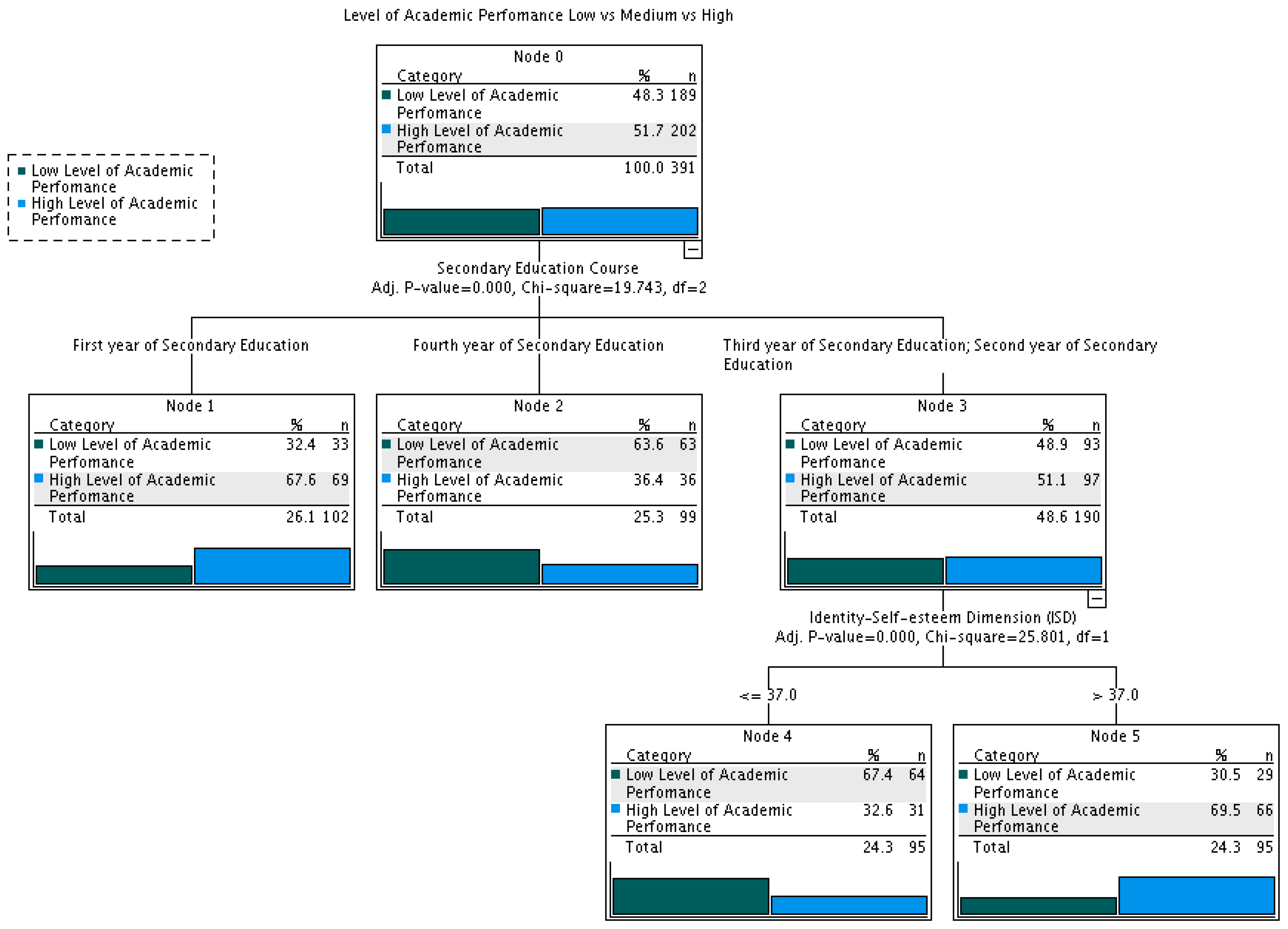

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abubakar, Usman, Nur Ain Shafiqah Mohd Azli, Izzatil Aqmar Hashim, Nur Fatin Adlin Kamarudin, Nur Ain Izzati Abdul Latif, Abdul Rahman Mohamad Badaruddin, Muhammad Zulkifli Razak, and Nur Ain Zaidan. 2021. The relationship between academic resilience and academic performance among pharmacy students. Pharmacy Education 21: 705–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agasisti, Tommaso, Francesco Avvisati, Francesca Borgonovi, and Sergio Longobardi. 2021. What school factors are associated with the success of socio-economically disadvantaged students? An empirical investigation using PISA data. Social Indicators Research 157: 749–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Dawood, Iftikhar Ahmad Baig, and Namra Munir. 2019. Relación del rendimiento académico con el estrés percibido y el índice de masa corporal. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores 57: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Aldana, Ruth, Yadira Beltrán-Márquez, Rosario Máfara-Duarte, and Zulema Gaytán-Martínez. 2016. Relación entre rendimiento académico y resiliencia en una universidad tecnológica. Revista de Investigaciones Sociales 2: 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, Carla Patricia, Luis Ángel Rueda Toncel, and Jainer Sardoth Blanchar. 2018. El rendimiento académico: Una problemática compleja. Revista Boletín Redipe 7: 137–41. [Google Scholar]

- Artunduaga, Néstor. 2024. Factores asociados al rendimiento académico en educación secundaria: Una revisión sistemática. Revista de Psicología y Educación 19: 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, Jessica L., Teresa Vega-Uriostegui, Daniel Norwood, and Maria Adamuti-Trache. 2023. Social and emotional learning and ninth-grade students’ academic achievement. Journal of Intelligence 11: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, Juan Carlos, and Guadalupe Manzano. 2018. Academic performance of first-year university students: The influence of resilience and engagement. Higher Education Research & Development 37: 1321–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila Francés, Mercedes, María Carmen Sánchez Pérez, and Andrea Bueno Baquero. 2022. Factores que facilitan y dificultan la transición de educación primaria a secundaria. Revista de Investigación Educativa 40: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, Ruth, Hadass Moore, Ron Avi Astor, and Rami Benbenishty. 2017. A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research 87: 425–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestué-Laguna, Marta, and Elena Escolano-Pérez. 2021. Implicación de la resiliencia y de las funciones ejecutivas en el rendimiento académico de educación obligatoria. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology 2: 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittmann, Felix. 2021. When problems just bounce back: About the relation between resilience and academic success in German tertiary education. SN Social Sciences 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Naranjo, Germania Maricela, Jenny Esmeralda Martínez-Benítez, Segundo Napoleón Barreno-Freire, and Oswaldo Fabián Haro-Jácome. 2021. Factores asociados al rendimiento académico: Un estudio de caso. Revista Educare 25: 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Brett A. 2020. Resiliency and academic achievement among urban high school students. Leadership and Research in Education: The Journal of the Ohio Council of Professors of Educational Administration (OCPEA) 5: 106–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cano Celestino, María Alicia, and Rosalinda Robles Rivera. 2018. Factores asociados al rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Mexicana de Orientación Eductativa 15: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, Simon. 2016. The Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30): A new multidimensional construct measure. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Ríos, Ana, Eugenio Saavedra Guajardo, and Claudio Rojas Jara. 2019. Contextos educativos urbanos y rurales vulnerables: Un estudio de resiliencia. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala 22: 2084–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, Dante, and Sheree L. Toth. 2009. The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: The coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 50: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros, Olga, and Benito León-del Barco. 2024. Análisis discriminante de las relaciones interpersonales positivas de aula y rendimiento académico en escolares chilenos. Educación XX1 27: 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, Shay M., Michael J. Mann, Alfgeir L. Kristjansson, Megan L. Smith, and Keith J. Zullig. 2019. School climate and academic achievement in middle and high school students. Journal of School Health 89: 173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, Shay M., Michael J. Mann, Christa L. Lilly, Angela M. Dyer, Megan L. Smith, and Alfgeir L. Kristjansson. 2020. School climate as an intervention to reduce academic failure and educate the whole child: A longitudinal study. Journal of School Health 90: 182–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas Herrera, Ximena, Silvana Godoy Mateus, Jorge Leonardo Duarte Rodríguez, and Diana Carolina López Vera. 2019. La resiliencia en el logro educativo de los estudiantes colombianos. Revista Colombiana de Educación 76: 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiastuti, Ike, Wiwin Hendriani, and Fitri Andriani. 2022. The impact of academic resilience on academic performance in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. KnE Social Sciences 7: 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, Cahit, and Metin Kaya. 2021. Socioeconomic status and wellbeing as predictors of students’ academic achievement: Evidence from a developing country. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 33: 202–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Castro, Jhon Franklin, Juan Hernández-Lalinde, Johel E. Rodríguez, Maricarmen Chacín, and Valmore Bermúdez-Pirela. 2020. Influencia del estrés sobre el rendimiento académico. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica 39: 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Etherton, Kent, Debra Steele-Johnson, Kathleen Salvano, and Nicholas Kovacs. 2020. Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: The role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. The Journal of General Psychology 149: 279–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo-Bullón, Fernando, María Maestre Campos, Elena Felipe Castaño, Benito León-del Barco, and María Isabel Polo del Río. 2017. Análisis del rendimiento académico de los alumnos de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria según las variables familiares. Educación XX1 20: 209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Guangbao, Philip Wing Keung Chan, and Penelope Kalogeropoulos. 2020. Social support and academic achievement of chinese low-income children: A mediation effect of academic resilience. International Journal of Psychological Research 13: 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, Katie A. 2019. Promoting a culture of bullying: Understanding the role of school climate and school sector. Journal of School Choice 13: 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, Pablo, Rosario Cabello, and María José Gutiérrez-Cobo. 2017. Avances en la investigación sobre competencias emocionales en educación. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 88: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Frias, Cindy E., Cecilia Cuzco, Carmen Frias Martín, Silvia Pérez-Ortega, Joselyn A. Triviño-López, and María Lombraña. 2020. Resilience and emotional support in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 58: 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos de Miguel, Jonatan. 2025. La resiliencia como predictor del rendimiento en adolescentes. Revista de Investigación Educativa 43: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Crespo, Francisco Javier, Javier Suárez-Álvarez, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, and José Muñiz. 2022. Academic resilience in Mathematics and Science: Europe TIMSS-2019 Data. Psicothema 34: 217–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Arratia, Norma Ivonne. 2016. Resiliencia y Personalidad en Niños. In Cómo Desarrollarse en Tiempos de Crisis, 2nd ed. Edited by Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. México: Eón. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Esquivel, Dulce Areli, Ulises Delgado Sánchez, Fernanda Gabriela Martínez Flores, María Araceli Ortiz-Rodríguez, and Rubén Avilés Reyes. 2021. Resiliencia, género y rendimiento académico en jóvenes universitarios del Estado de Morelos. Revista ConCiencia EPG 6: 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Dávila, Felicita Dora, Yenifer Milagros Pérez-Moreano, and Dante Manuel Macazana-Fernández. 2019. Pensamiento crítico y su relación con el rendimiento académico en la investigación formativa de los estudiantes universitarios. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores 13: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haktanir, Abdulkadir, Joshua C. Watson, Hulya Ermis-Demirtas, Mehmet A. Karaman, Paula D. Freeman, Ajitha Kuraman, and Ashley Streeter. 2021. Resilience, academic self-concept, and college adjustment among first-year students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory y Practice 23: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Muñoz, Melissa, Azael Sanjur, and Noemí Montes. 2024. Resiliencia y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de Educación Básica General. Revista Ecuatoriana de Psicología 7: 114–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jun Sung, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Jeoung Min Lee. 2018. School climate and bullying prevention programs. In The Wiley Handbook on Violence in Education. Edited by Harvey Shapiro. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 359–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotliarenco, María Angélica. 2021. Resiliencia y su Importancia en la Educación del Grupo Familiar, fundamentalmente la Madre, y en el Crecimiento y Desarrollo de los Niños y Niñas. Santiago: CEANIM. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, Jeffrey, Qian Cao, Jan N. Hughes, and Marike H. F. Deutz. 2018. Academic resilience despite early academic adversity: A three-wave longitudinal study on regulation-related resiliency, interpersonal relationships, and achievement in first to third grade. Early Education and Development 29: 762–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, Caroline, Susan Beltman, Noelene Weatherby-Fell, and Tania Broadley. 2021. Classroom ready? Building resilience and professional experience in teacher education. In Teacher Education: Innovation, Intervention and Impact. Edited by Robyn Brandenburg, Sharon McDonough, Jenene Burke and Simone White. Singapore: Springer, pp. 211–29. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andrew J., and Herbert W. Marsh. 2008. Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. Journal of School Psychology 46: 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Romero, Nuria, and Álvaro Sánchez-López. 2021. Factores motivacionales y de autoconcepto implicados en la predicción del rendimiento académico en Educación Secundaria. Apuntes de Psicología 39: 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Aller, Álvaro, Álvaro Postigo, Covadonga González-Nuevo, Marcelino Cuesta, Rubén Fernández-Alonso, Marcos Álvarez-Díaz, Eduardo García-Cueto, and José Muñiz. 2021. Resiliencia académica: La influencia del esfuerzo, las expectativas y el autoconcepto académico. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 53: 114–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. 2022. Programa para la Evaluación Internacional de los Alumnos PISA (OCDE) 2022 (Informe español). Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica del MECD. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. 2024. Informe 2024 sobre el estado del sistema educativo. Curso 2022–2023. Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica del MECD. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Asch, Jesús. 2021. El análisis de la resiliencia y el rendimiento académico en los estudiantes universitarios. Revista Nacional de Administración 12: 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Amanda Sheffield, Jennifer Hays-Grudo, Kara L. Kerr, and Lana O. Beasley. 2021. The heart of the matter: Developing the whole child through community resources and caregiver relationships. Development and Psychopathology 33: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera-Saucedo, Jessica, Martha Leticia Salazar Garza, María de los Ángeles Vacio Muro, and Silvia Morales Chainé. 2020. Evaluación de la autoeficacia, expectativas y metas académicas asociadas al rendimiento escolar. Revista de Investigación Educativa 38: 435–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, Lisa A., Daniel A. DeCino, Daniel J. Mourlam, and Gabrielle A. Strouse. 2019. School climate, emotions, and relationships: Children’s experiences of well-being in the Midwestern U.S. International Journal of Emotional Education Special Issue 11: 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Niño-Tezén, Angélica Lourdes, José Melanio Ramírez Alva, July Antonieta Chávez Lozada, and Patricia Yolanda Santos Vera. 2024. Resiliencia y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios de psicología de Perú. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 27: 173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, José Carlos, María del Carmen Perálvarez-Estevez, Ellián Tuero, and Natalia Suárez. 2024. Autoconcepto, motivación académica, actitud hacia el aprendizaje y rendimiento académico: Un estudio centrado en la persona. Revista de Psicología y Educación 19: 107–16. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, Jelena, Nicole R. Bush, Juliet Stamperdahl, Nancy E. Adler, and W. Thomas Boyce. 2010. Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effects of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness. Child Development 81: 270–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oducado, Ryan Michael, Geneveve Parreño-Lachica, and Judith Rabacal. 2021. Personal resilience and its influence on COVID- 19 stress, anxiety and fear among graduate students in the Philippines. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation 15: 431–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ononye, Uzoma, Mercy Ogbeta, Francis Ndudi, Dudutari Bereprebofa, and Ikechuckwu Maduemezia. 2022. Academic resilience, emotional intelligence, and academic performance among undergraduate students. Knowledge and Performance Management 6: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paechter, Manuela, Hellen Phan-Lesti, Bernhard Ertl, Daniel Macher, Smirna Malkoc, and Ilona Papousek. 2022. Learning in adverse circumstances: Impaired by learning with anxiety, maladaptive cognitions, and emotions, but supported by self-concept and motivation. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes-Valverde, Yolanda, Rosel Quispe-Herrera, and Jorge S. Garate-Quispe. 2020. Relationships among self-efficacy, self-concepts and academic achievement in university students of Peruvian Amazon. Revista Espacios 41: 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Mármol, Mariana, Manuel Castro-Sánchez, Ramón Chacón-Cuberos, and María Alejandra Gamarra-Vengoechea. 2023. Relación entre rendimiento académico, factores psicosociales y hábitos saludables en alumnos de Educación Secundaria. Aula Abierta 52: 281–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Blasco, Valentín, and Fernando Martínez-Abad. 2024. Revisión sistemática sobre la relación resiliencia-rendimiento académico del alumnado en educación obligatoria: Análisis de evaluaciones a gran escala. Aula Abierta 53: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Pérez, Natalie. 2023. Análisis de la integración del concepto resiliencia en la planeación de la Ciudad de México. Economía, Sociedad y Territorio 23: 131–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Morente, Agnès, Gemma Filella-Guiu, Ramona Ribes-Castells, and Núria Pérez-Escoda. 2017. Análisis de la relación entre competencias emocionales, autoestima, clima de aula, rendimiento académico y nivel de bienestar en educación primaria. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 28: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, Eugenio, and Ana Castro. 2009. Escala de Resiliencia Escolar (E.R.E.) para Niños entre 9 y 14 Años. Santiago: CEANIM. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoughi, Majid. 2018. The relationship between academic self-efficacy, academic resilience, academic adjustment, and academic performance among medical students. Education Strategies in Medical Sciences 11: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Cretton, Ximena, and Nelson Castro Méndez. 2022. Competencias socioemocionales y resiliencia de estudiantes de escuelas vulnerables y su relación con el rendimiento académico. Revista de Psicología 40: 879–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supervía, Usán P., Salavera C. Bordás, and Quílez A. Robres. 2022. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between resilience and academic performance in adolescence. Learning and Motivation 78: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipismana, Orlando. 2019. Factores de resiliencia y afrontamiento como predictores del rendimiento académico de los estudiantes en universidades privadas. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 17: 147–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, Michael, ed. 2012. Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience. In The Social Ecology of Resilience; A Handbook of Theory and Practice. New York: Springer, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, Jorge J., David Sirlopú, Roberto Melipillán, Dorothy Espelage, Jennifer Green, and Javier Guzmán. 2019. Exploring the influence school climate on the relationship between school violence and adolescent subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research 12: 2095–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Díaz, Marta. 2024. Motivación y rendimiento académico en las distintas asignaturas de secundaria: Factores influyentes. Cuestiones Pedagógicas 1: 263–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, Christian E., and Anthony W. Sali. 2023. Resilience as the ability to maintain well-being: An allostatic active inference model. Journal of Intelligence 11: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, Fabian, Nicole Nagy, Friederike Helm, and Jens Möller. 2018. Testing the internal/external frame of reference model of academic achievement and academic self-concept with open self-concept reports. Learning and Instruction 55: 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumárraga-Espinosa, Marcos. 2023. Resiliencia académica, rendimiento e intención de abandono en estudiantes universitarios de Quito. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud 21: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ² | χ²/df | GFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 related factors and 2 second-order factors | 1058.976 | 3.664 | 0.989 | 0.900 | 0.864 | 0.888 | 0.056 | 0.060 |

| Academic Performance Levels | ANOVA Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRS Dimensions | Low Level M (SD) | Medium Level M (SD) | High Level M (SD) | F | p | η2 * |

| ISD | 34.91 (5.91) | 35.67 (5.52) | 38.28 (3.94) | 23.060 | .000 | 0.07 |

| NMD | 38.01 (5.71) | 38.98 (5.85) | 40.67 (4.11) | 12.772 | .000 | 0.04 |

| LGD | 37.83 (5.59) | 38.03 (5.41) | 40.12 (4.01) | 12.692 | .000 | 0.04 |

| IRD | 51.66 (8.22) | 53.27 (7.33) | 56.57 (4.97) | 25.578 | .000 | 0.08 |

| ERD | 59.08 (8.98) | 59.42 (9.06) | 62.50 (6.55) | 10.375 | .000 | 0.03 |

| Variables | Functions | |

|---|---|---|

| Function 1 | Function 2 | |

| Internal Resources (IRD) | 0.997 * | −0.079 |

| Identity–Self-esteem (ISD) | 0.944 * | 0.184 |

| Networks–Models (NMD) | 0.703 * | −0.134 |

| Learning-Generativity (LGD) | 0.686 * | 0.369 |

| External Resources (ERD) | 0.622 * | 0.321 |

| Predicted Membership Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Levels | Low | Medium | High | |

| % | Low | 40.2 | 21.2 | 38.6 |

| Medium | 29.4 | 31.2 | 39.4 | |

| High | 20.8 | 20.3 | 58.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carroza-Pacheco, A.M.; León-del-Barco, B.; Bringas Molleda, C. Academic Performance and Resilience in Secondary Education Students. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050056

Carroza-Pacheco AM, León-del-Barco B, Bringas Molleda C. Academic Performance and Resilience in Secondary Education Students. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(5):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050056

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarroza-Pacheco, Ana María, Benito León-del-Barco, and Carolina Bringas Molleda. 2025. "Academic Performance and Resilience in Secondary Education Students" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 5: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050056

APA StyleCarroza-Pacheco, A. M., León-del-Barco, B., & Bringas Molleda, C. (2025). Academic Performance and Resilience in Secondary Education Students. Journal of Intelligence, 13(5), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050056