Effects of Peer and Teacher Support on Students’ Creative Thinking: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Emotion Regulation Strategy as a Moderator

Abstract

1. Introduction

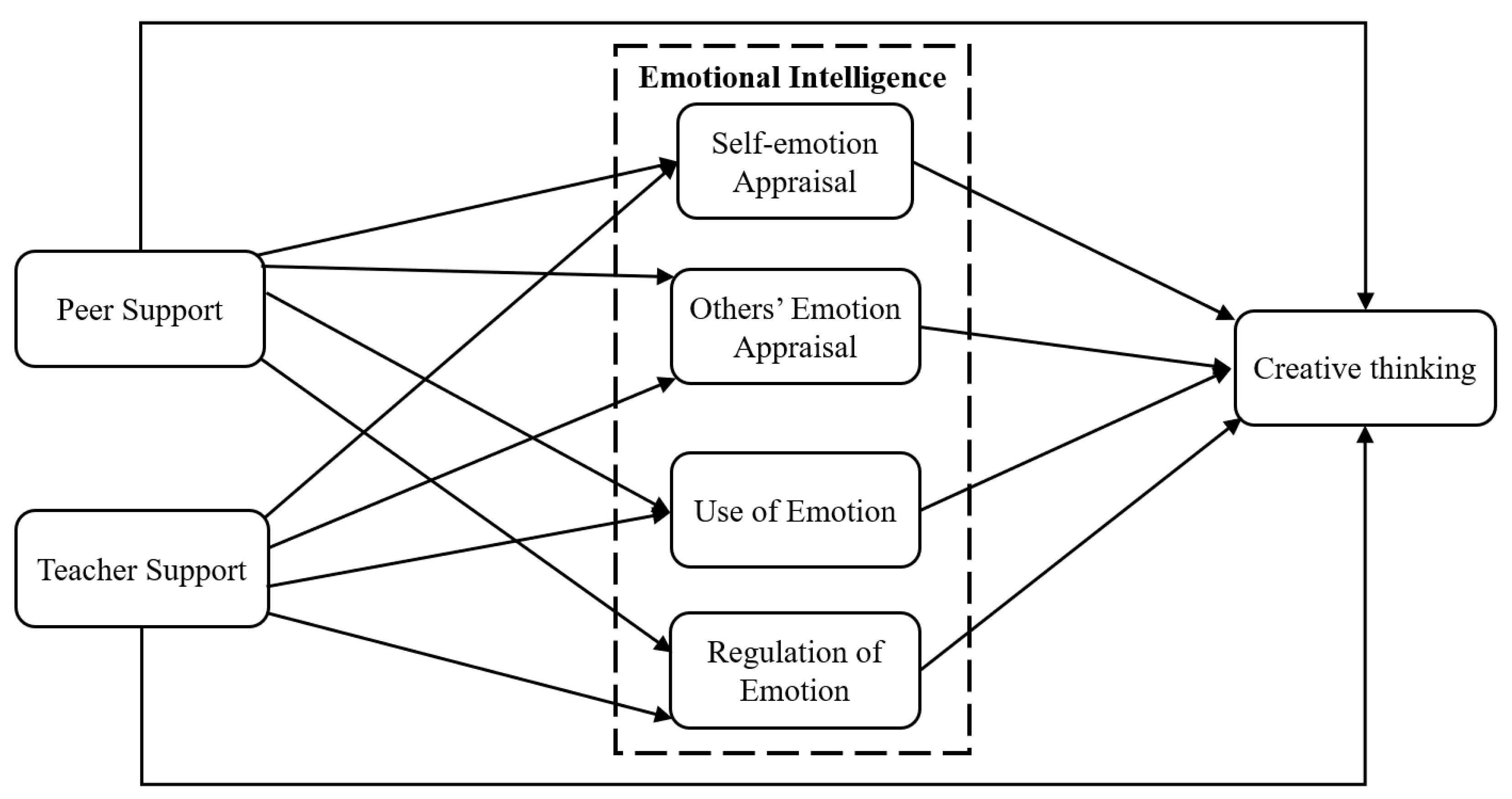

2. Theoretical Framework and Model Development

2.1. Creative Thinking

2.2. Peer Support and Creative Thinking

2.3. Teacher Support and Creative Thinking

2.4. Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence

2.5. Moderating Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies

2.6. The Current Study

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Teacher Support Scale

3.2.2. Peer Support Scale

3.2.3. Emotional Intelligence Scale

3.2.4. Emotion Regulation Strategies Scale

3.2.5. Creative Thinking Scale

3.3. Date Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

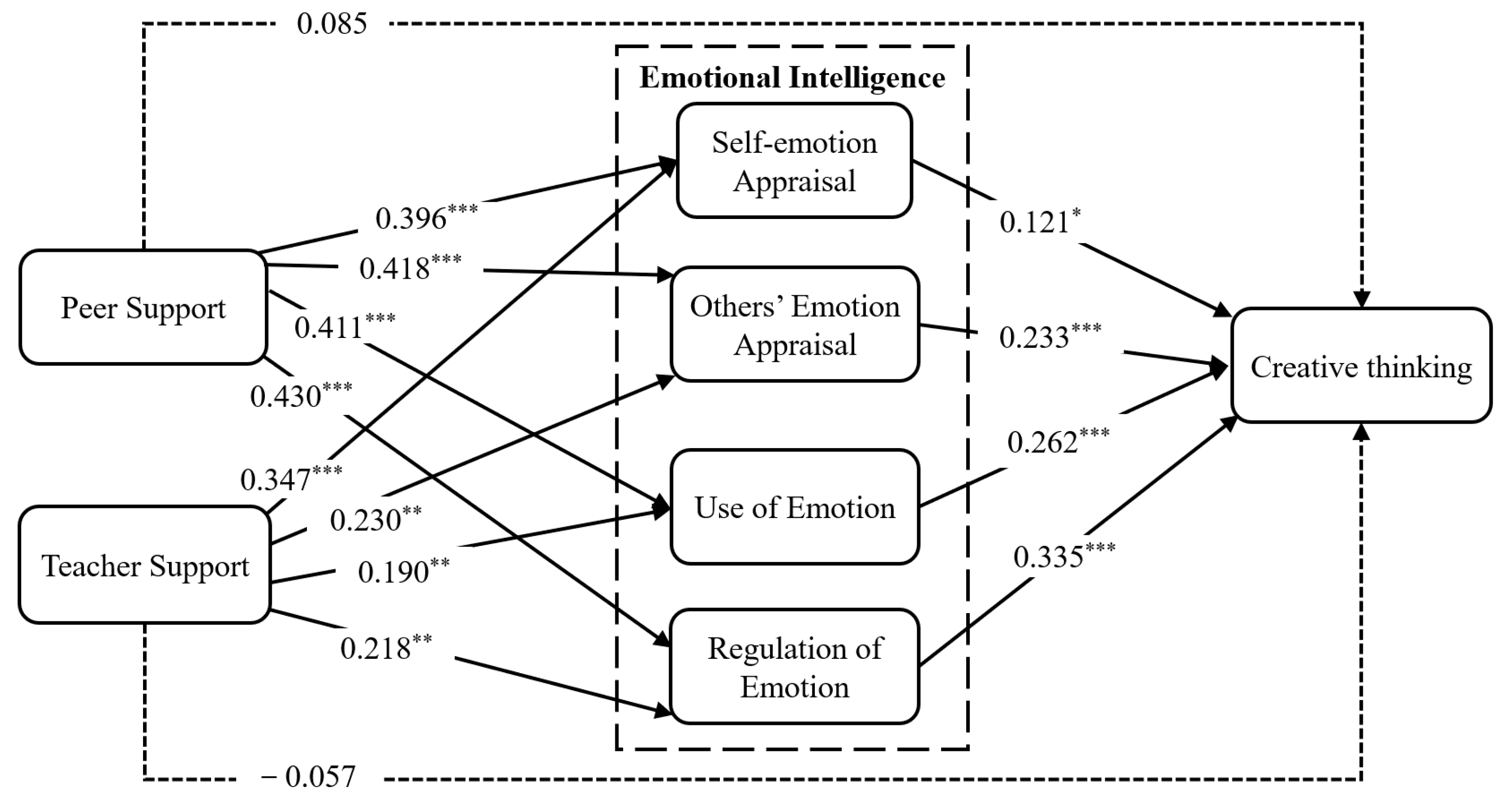

4.2. Assessment of Structural Model

4.3. Testing for the Mediating Effect of Emotional Intelligence

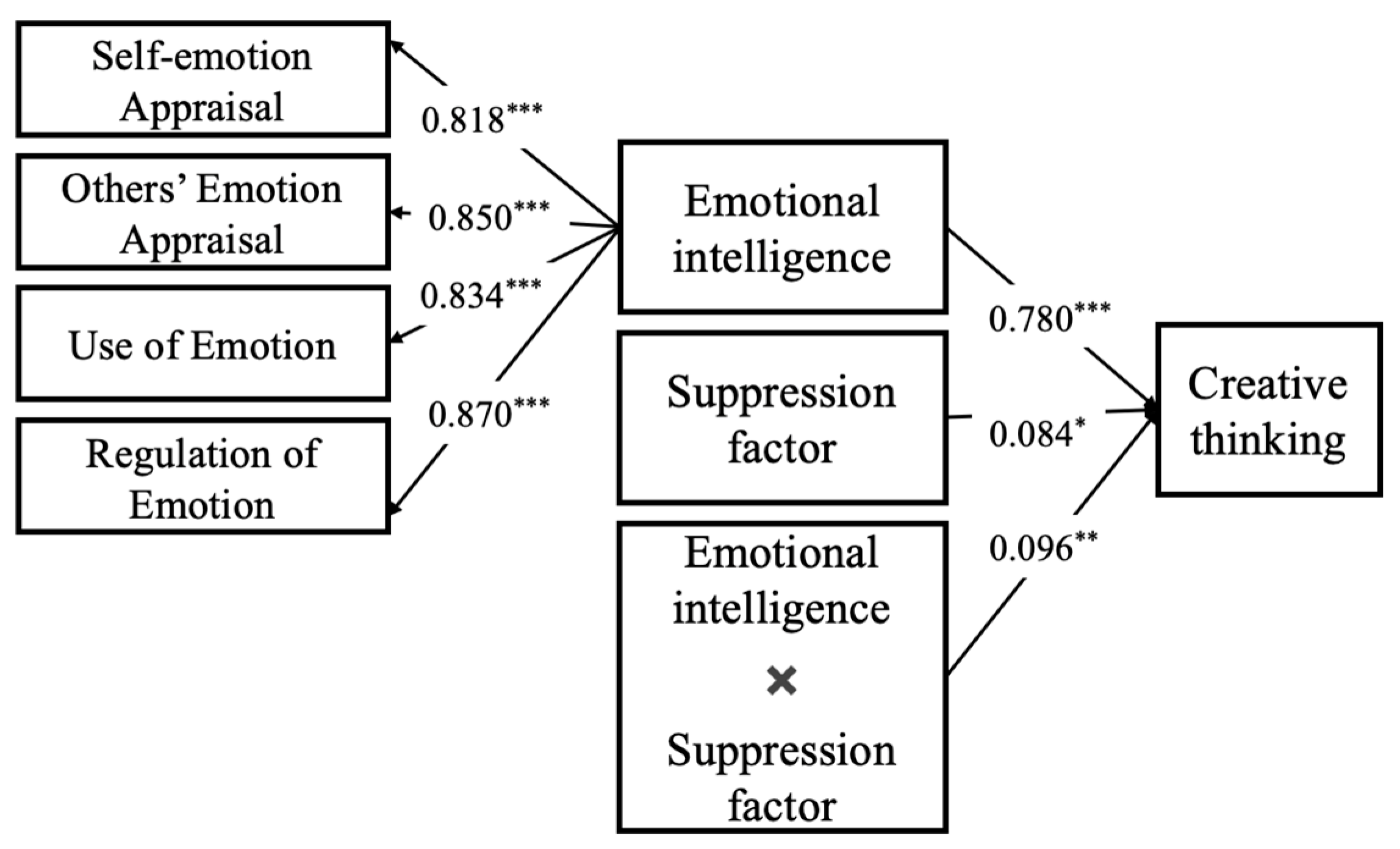

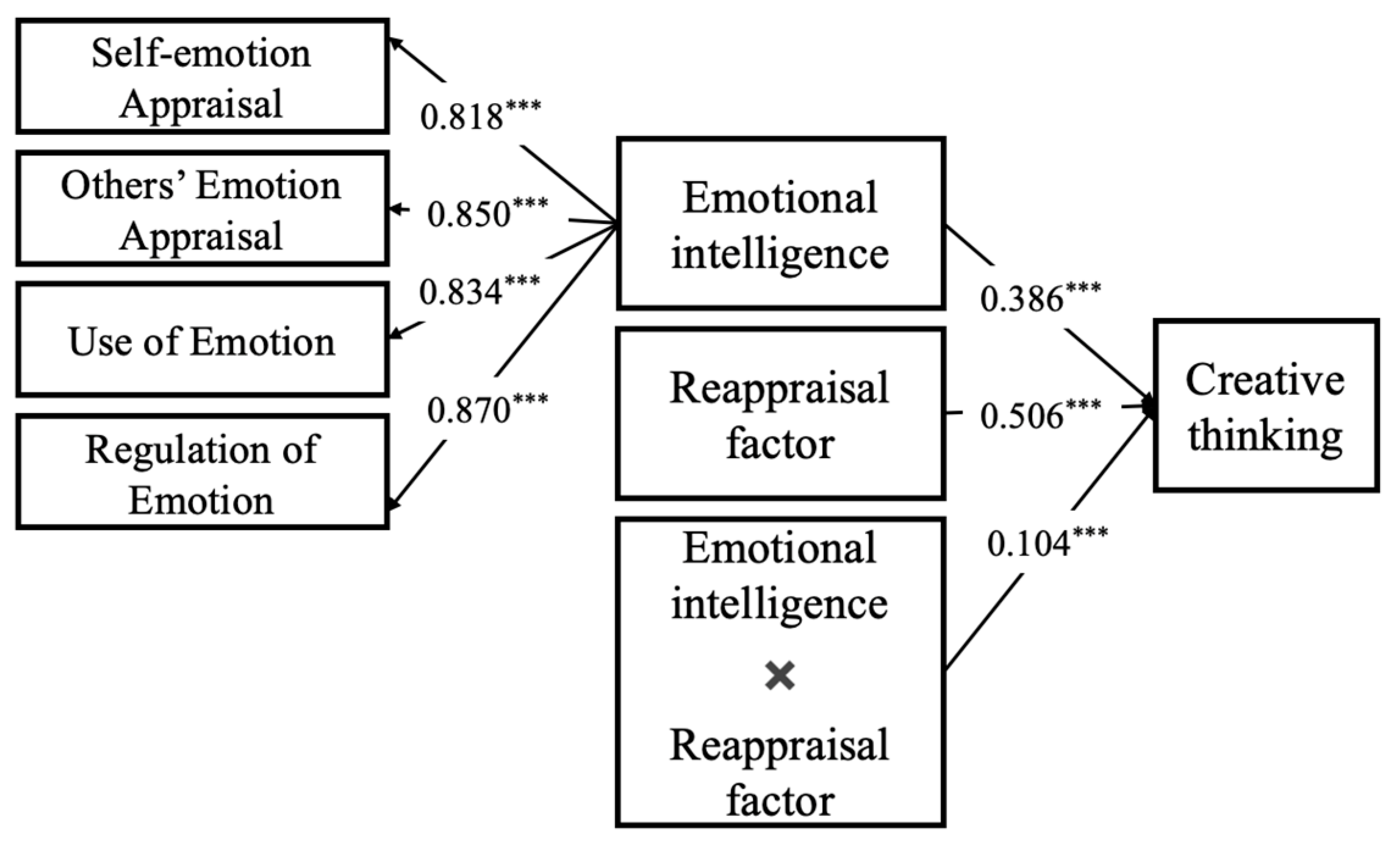

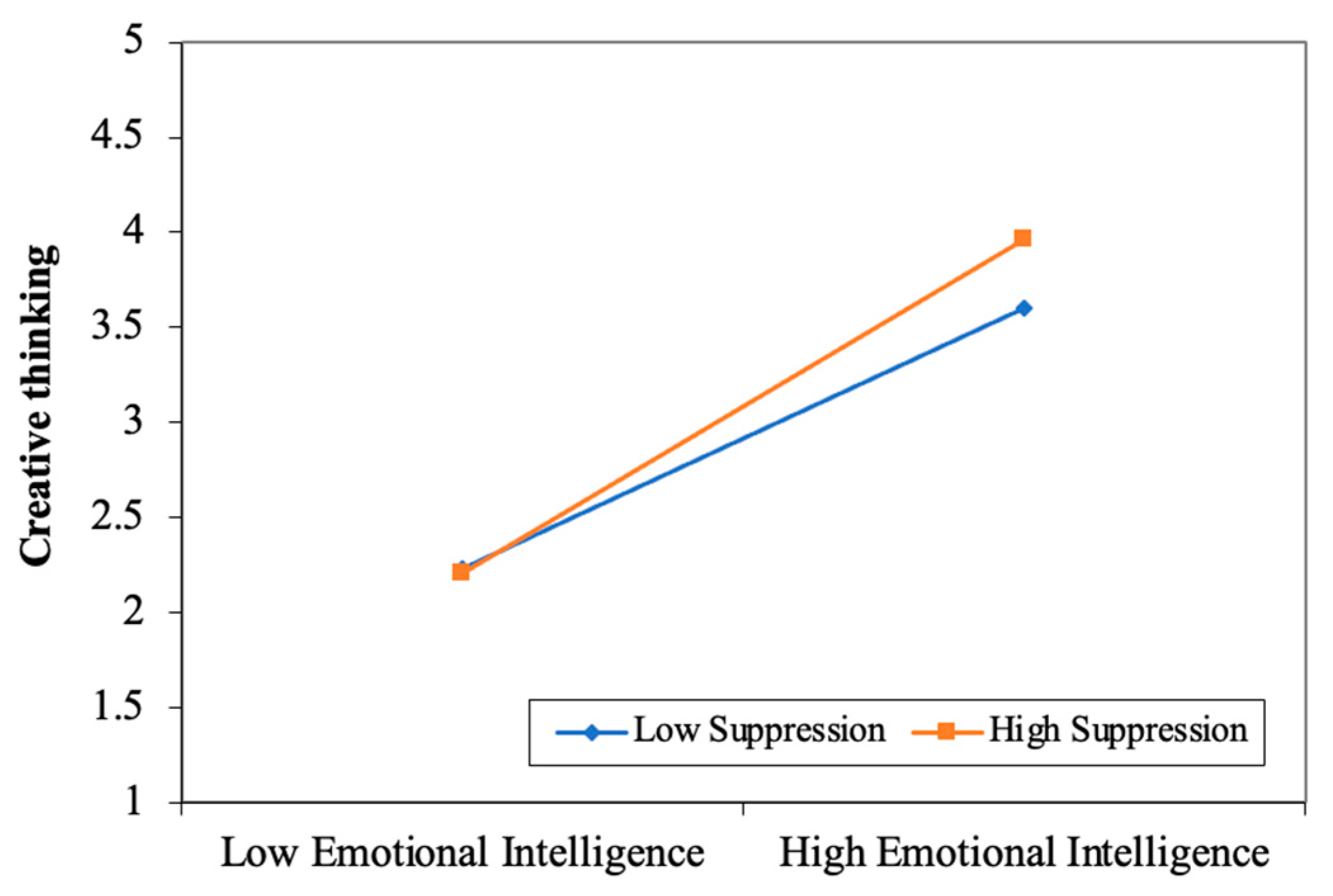

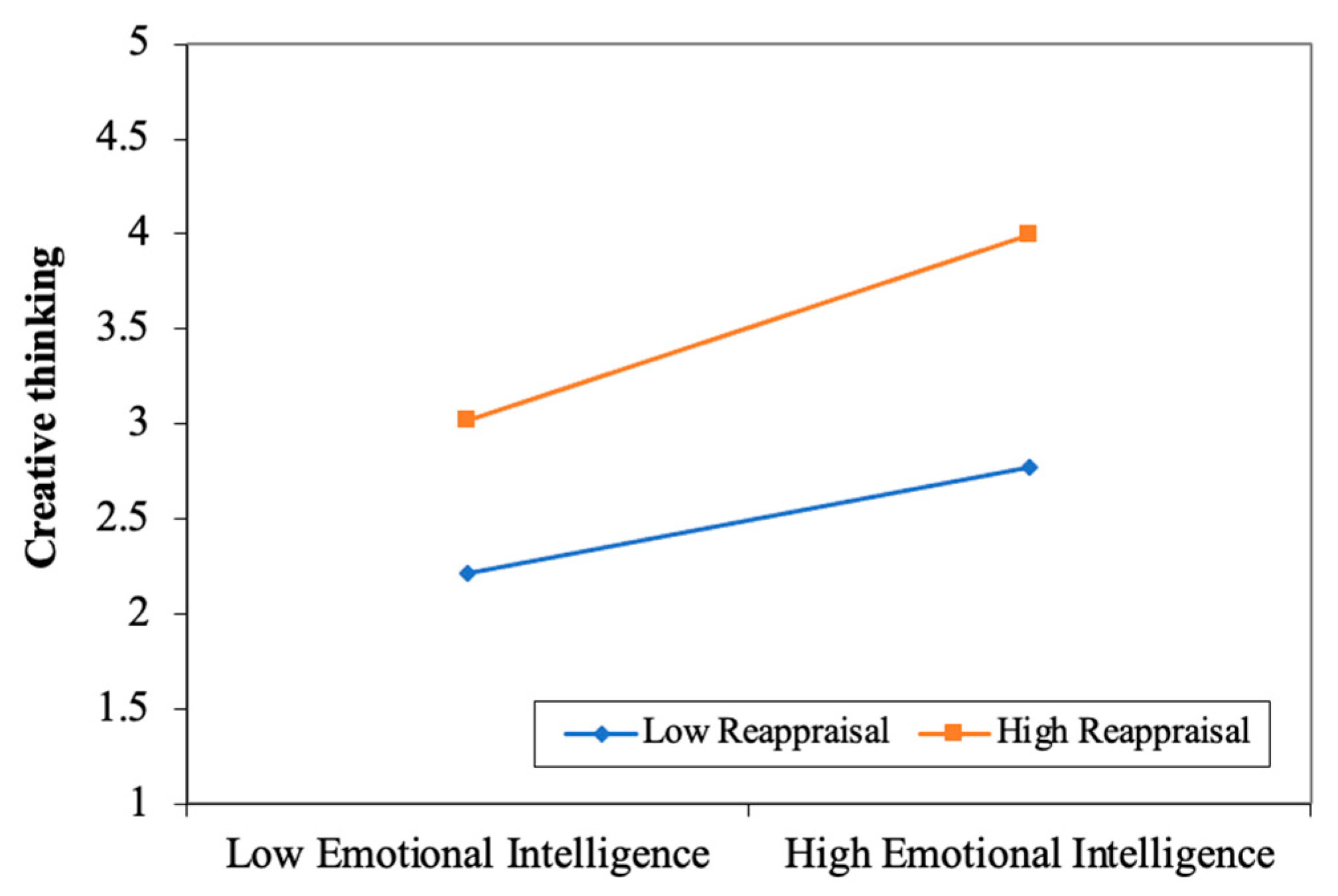

4.4. Testing for the Moderating Effect of Emotion Regulation Strategies

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations, Future Research, and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Affuso, Gaetana, Anna Zannone, Concetta Esposito, Maddalena Pannone, Maria Concetta Miranda, Grazia De Angelis, Serena Aquilar, Mirella Dragone, and Dario Bacchini. 2023. The effects of teacher support, parental monitoring, motivation and self-efficacy on academic performance over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education 38: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, Hassan Soodmand, and Masoud Rahimi. 2016. Reflective thinking, emotional intelligence, and speaking ability of EFL learners: Is there a relation? Thinking Skills and Creativity 19: 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpur, Uğur. 2020. Critical, reflective, creative thinking and their reflections on academic achievement. Thinking Skills and Creativity 37: 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, Adnan Yousef, and Rasha Ahmed Al-Shoboul. 2018. Emotional support and its relationship to Emotional intelligence. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 5: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, Ümmühan, and Hatice Yildiz Durak. 2023. Innovative thinking skills and creative thinking dispositions in learning environments: Antecedents and consequences. Thinking Skills and Creativity 47: 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, Pınar, and Adem Yilmaz. 2021. ‘Moving the Kaleidoscope’ to see the effect of creative personality traits on creative thinking dispositions of preservice teachers: The mediating effect of creative learning environments and teachers’ creativity fostering behavior. Thinking Skills and Creativity 41: 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Youjae Yi. 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariola, Emily, Eleonora Gullone, and Elizabeth K. Hughes. 2011. Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 14: 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, Théo, Juliette Richetin, and Oulmann Zerhouni. 2023. Effect of emotion dysregulation and emotion regulation strategies on evaluative conditioning. Learning and Motivation 82: 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, Jasperina, Carlos A. De Matos Fernandes, Christian E. G. Steglich, Ellen P. W. A. Jansen, W. H. Adriaan Hofman, and Andreas Flache. 2022. The development of peer networks and academic performance in learning communities in higher education. Learning and Instruction 80: 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Birol. 2019. The impact of peer instruction on academic achievements and creative thinking skills of college students. International Journal of Educational Methodology 5: 503–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale-Berkowitz, Norian A. 2022. Let’s teach peer support skills to all college students: Here’s how and why. Journal of American College Health 70: 1921–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Alexander S. McKay, and James C. Kaufman. 2014. Emotional intelligence and creativity: The mediating role of generosity and vigor. The Journal of Creative Behavior 48: 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cuberos, Ramón, Eva María Olmedo-Moreno, Amador Jesús Lara-Sánchez, Félix Zurita-Ortega, and Manuel Castro-Sánchez. 2021. Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: A structural model according to branch of knowledge. Studies in Higher Education 46: 1421–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Boon How, Azhar Md Zain, and Faezah Hassan. 2013. Emotional intelligence and academic performance in first and final year medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education 13: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Wynne W. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research. Edited by George A. Marcoulides. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali, Mahlagha, Levent Altinay, and Glauco De Vita. 2018. Emotional intelligence and creative performance: Looking through the lens of environmental uncertainty and cultural intelligence. International Journal of Hospitality Management 73: 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Mary Rose, and Diana R. Samek. 2022. Parent and peer social-emotional support as predictors of depressive symptoms in the transition into and out of college. Personality and Individual Differences 192: 111588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Julia, Anna-Lena Dicke, Bärbel Kracke, and Peter Noack. 2015. Teacher support and its influence on students’ intrinsic value and effort: Dimensional comparison effects across subjects. Learning and Instruction 39: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, Annamaria, and Maureen E. Kenny. 2011. Promoting emotional intelligence and career decision making among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Assessment 19: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, Annamaria, and Maureen E. Kenny. 2015. The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among Italian youth. Journal of Career Development 42: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Gordon, Katherine L., Amelia Aldao, and Andres De Los Reyes. 2015. Emotion regulation in context: Examining the spontaneous use of strategies across emotional intensity and type of emotion. Personality and Individual Differences 86: 271–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovyk, Svitlana H., Alexander Ya Mytnyk, Nataliia O. Mykhalchuk, Ernest E. Ivashkevych, and Nataliia O. Khupavtseva. 2020. Preparing future teachers for the development of students’ emotional intelligence. Journal of Intellectual Disability–Diagnosis and Treatment 8: 430–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnali, Mehmet, Şenol Orakci, and Tahmineh Khalili. 2023. Fostering creative thinking skills to burst the effect of emotional intelligence on entrepreneurial skills. Thinking Skills and Creativity 47: 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Mohammad Reza, Tahereh Heydarnejad, and Hossein Najjari. 2018. The interplay among emotions, creativity and emotional intelligence: A case of Iranian EFL teachers. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies 6: 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Fabio, Annamaria Di, and Maureen E. Kenny. 2012. Emotional intelligence and perceived social support among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Development 39: 461–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, Roger A., and Einar M. Skaalvik. 2014. Students’ perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: Relations with motivational and emotional responses. International Education Studies 7: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Perez, Virginia, and Rodrigo Martin-Rojas. 2022. Emotional competencies as drivers of management students’ academic performance: The moderating effects of cooperative learning. International Journal of Management Education 20: 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, Emanuele, Simona Andreea Popușoi, Andrei Corneliu Holman, Alyson Blanchard, Paolo Iliceto, and Nadja Heym. 2023. The dark tetrad and trait emotional intelligence: Latent profile analysis and relationships with PID-5 maladaptive personality trait domains. Personality and Individual Differences 205: 112092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Zihan, and Yingli Yang. 2023. The predictive effect of trait emotional intelligence on emotion regulation strategies: The mediating role of negative emotion intensity. System 112: 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherasim, Loredana Ruxandra, Simona Butnaru, and Cornelia Mairean. 2013. Classroom environment, achievement goals and maths performance: Gender differences. Educational Studies 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacumo, Lisa A., and Wilhelmina Savenye. 2020. Asynchronous discussion forum design to support cognition: Effects of rubrics and instructor prompts on learner’s critical thinking, achievement, and satisfaction. Educational Technology Research and Development 68: 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2022. Divergent but not Convergent Thinking Mediates the Trait Emotional Intelligence-Real-World Creativity Link: An Empirical Study. Creativity Research Journal 36: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2024. Reappraise and be mindful! The key role of cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness in the association between openness to experience and divergent thinking. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 36: 834–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidugu, Vasudha, E. Sally Rogers, Steven Harrington, Mihoko Maru, Gene Johnson, Julie Cohee, and Jennifer Hinkel. 2015. Individual peer support: A qualitative study of mechanisms of its effectiveness. Community Mental Health Journal 51: 445–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Shiqi. 2020. On the Cultivation of Middle School Students’ Creativity. English Language Teaching 13: 134–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, Emma, Mariale Hardiman, Julia Yarmolinskaya, Luke Rinne, and Charles Limb. 2013. Building creative thinking in the classroom: From research to practice. International Journal of Educational Research 62: 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Jacquelyn T., and Jude Cassidy. 2019. Expressive suppression of negative emotions in children and adolescents: Theory, data, and a guide for future research. Developmental Psychology 55: 1938–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J. 2002. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J., and Oliver P. John. 2003. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadar, Linor L., and Mor Tirosh. 2019. Creative thinking in mathematics curriculum: An analytic framework. Thinking Skills and Creativity 33: 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Marko Sarstedt, Christian M. Ringle, and Jeannette A. Mena. 2012. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40: 414–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph. F., Hult G. Tomas, M. Ringle, M. Christian., and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, Andy. 2000. Mixed emotions: Teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education 16: 811–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, Marjorie J., James D. A. Parker, Judith Wiener, Carolyn Watters, Laura M. Wood, and Amber Oke. 2010. Academic success in adolescence: Relationships among verbal IQ, social support and emotional intelligence. Australian Journal of Psychology 62: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstra, Lisette, Kim Stroet, and Desirée Weijers. 2021. Profiles of teachers’ need-support: How do autonomy support, structure, and involvement cohere and predict motivation and learning outcomes? Teaching and Teacher Education 99: 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Ridong, Yi-Yong Wu, and Chich-Jen Shieh. 2016. Effects of virtual reality integrated creative thinking instruction on students’ creative thinking abilities. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 12: 477–86. [Google Scholar]

- Isen, Alice M., Kimberly A. Daubman, and Gary P. Nowicki. 1987. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 1122–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Zorana, and Marc A. Brackett. 2015. Predicting creativity: Interactive effects of openness to experience and emotion regulation ability. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 9: 480–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, Md Hassan. 2018. Moderating role of job autonomy and supervisor support in trait emotional intelligence and employee creativity relationship. Vision 22: 253–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani-Vahid, Leila, GolamAli Afrooz, Mohsen Shokoohi-Yekta, Kamal Kharrazi, and Bagher Ghobari. 2017. Can a creative interpersonal problem solving program improve creative thinking in gifted elementary students? Thinking Skills and Creativity 24: 175–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashy-Rosenbaum, Gabriela, Oren Kaplan, and Yael Israel-Cohen. 2018. Predicting academic achievement by class-level emotions and perceived homeroom teachers’ emotional support. Psychology in the Schools 55: 770–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Mandeep. 2017. Six thinking hats: An instructional strategy for developing creative thinking. International Journal of Research in Social Sciences 7: 520–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, Ümre, Semih Kaynak, and Seda Sevgili Koçak. 2023. The pathway from perceived peer support to achievement via school motivation in girls and boys: A moderated-mediation analysis. RMLE Online 46: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Feng, Jingjing Zhao, and Xuqun You. 2012. Emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in Chinese university students: The mediating role of self-esteem and social support. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 1039–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Kristen. N. 2020. Cultivating creative thinking in the classroom. In Methods and Materials for Teaching the Gifted, 5th ed. Edited by Jennifer H. Robins, Jennifer L. Jolly, Frances A. Karnes and Suzanne M. Bean. New York: Routledge, pp. 279–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yen-Fen, Chi-Jen Lin, Gwo-Jen Hwang, Qing-Ke Fu, and Weu-Hui Tseng. 2021. Effects of a mobile-based progressive peer-feedback scaffolding strategy on students’ creative thinking performance, metacognitive awareness, and learning attitude. Interactive Learning Environments 31: 2986–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberger-Truelove, Matthew E., Kira J. Carbonneau, David J. Atencio, Almut K. Zieher, and Alfredo F. Palacios. 2018. Self-regulatory growth effects for young children participating in a combined social and emotional learning and mindfulness-based intervention. Journal of Counseling & Development 96: 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuan, Kun Li, Wenqi Wei, Jianyu Dong, Canfei Wang, Ying Fu, Jiaxin Li, and Xin Peng. 2021. Critical thinking, emotional intelligence and conflict management styles of medical students: A cross-sectional study. Thinking Skills and Creativity 40: 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jiabin, Shuaijun You, Yaoqi Jiang, Xin Feng, Chaorong Song, Linwei Yu, and Lan Jiao. 2023. Associations between social networks and creative behavior during adolescence: The mediating effect of psychological capital. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Lin, Jon-Chao Hong, Miao Cao, Yan Dong, and Xiaoju Hou. 2023. Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: A structural equation model. Interactive Learning Environments 31: 1703–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, John D., Richard D. Roberts, and Sigal G. Barsade. 2008. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology 59: 507–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, Shery, and Cheryl MacNeil. 2006. Peer support: What makes it unique. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 10: 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, Shery, David Hilton, and Laurie Curtis. 2001. Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25: 134–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendzheritskaya, Julia, and Miriam Hansen. 2019. The role of emotions in higher education teaching and learning processes. Studies in Higher Education 44: 1709–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, Eileen G., Shannon B. Wanless, Sara E. Rimm-Kaufman, Claire Cameron, and James L. Peugh. 2012. The contribution of teachers’ emotional support to children’s social behaviors and self-regulatory skills in first grade. School Psychology Review 41: 141–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Shweta. 2020. Social networks, social capital, social support and academic success in higher education: A systematic review with a special focus on ‘underrepresented’ students. Educational Research Review 29: 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Rafael. 2023. Peer support in sub-Saharan Africa: A critical interpretive synthesis of school-based research. International Journal of Educational Development 96: 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, Salwa. 2016. Investigating mathematics teacher’s role to improve students’ creative thinking. American Journal of Educational Research 4: 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A., and H. C. Janeke. 2009. The relationship between thinking styles and emotional intelligence: An exploratory study. South African Journal of Psychology 39: 357–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, Suwastika, Anand Chand, Atishwar Pandaram, and Arvind Patel. 2023. Problematic internet and social network site use in young adults: The role of emotional intelligence and fear of negative evaluation. Personality and Individual Differences 200: 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, Francesca, Michela Calzolari, Sara Di Pietro, Nicola Pagnucci, Milko Zanini, Gianluca Catania, Giuseppe Aleo, Lisa Gomes, Loredana Sasso, and Annamaria Bagnasco. 2024. Pedagogical strategies to improve emotional competencies in nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today 142: 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olana, Ejigu, and Belay Tefera. 2022. Family, teachers and peer support as predictors of school engagement among secondary school Ethiopian adolescent students. Cogent Psychology 9: 2123586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orakci, Şenol, and Mehmet Durnali. 2023. The mediating effects of metacognition and creative thinking on the relationship between teachers’ autonomy support and teachers’ self-efficacy. Psychology in the Schools 60: 162–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgenel, Mustafa, and Münevver Çetin. 2017. Marmara yaratıcı düşünme eğilimleri ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Marmara Üniversitesi Atatürk Eğitim Fakültesi Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 46: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, Michael R., Myeong-Gu Seo, and Elad N. Sherf. 2015. Regulating and facilitating: The role of emotional intelligence in maintaining and using positive affect for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology 100: 917–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, Helen, Allison M. Ryan, and Avi Kaplan. 2007. Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology 99: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, Lorraine Dacre, and Pamela Qualter. 2012. Improving emotional intelligence and emotional self-efficacy through a teaching intervention for university students. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 306–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, Laura Navarro, and Helena Chacón-López. 2021. The impact of musical improvisation on children’s creative thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity 40: 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, Luciano, Xin Tang, Lauri Hietajärvi, Katariina Salmela-Aro, and Caterina Fiorilli. 2020. Students’ trait emotional intelligence and perceived teacher emotional support in preventing burnout: The moderating role of academic anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzek, Erik A., Christopher A. Hafen, Joseph P. Allen, Anne Gregory, Amori Yee Mikami, and Robert C. Pianta. 2016. How teacher emotional support motivates students: The mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learning and Instruction 42: 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggar, Manish, Eve-Marie Quintin, Nicholas T. Bott, Eliza Kienitz, Yin-hsuan Chien, Daniel WC Hong, Ning Liu, Adam Royalty, Grace Hawthorne, and Allan L. Reiss. 2017. Changes in brain activation associated with spontaneous improvization and figural creativity after design-thinking-based training: A longitudinal fMRI study. Cerebral Cortex 27: 3542–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, Feyzullah, Esin Özer, and Mehmet Engin Deniz. 2016. The predictive level of emotional intelligence for the domain-specific creativity: A study on gifted students. Egitim Ve Bilim-Education and Science 41: 181–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, Peter, and John D. Mayer. 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9: 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Álvarez, Nicolás, María Pilar Berrios Martos, and Natalio Extremera. 2020. A meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic performance in secondary education: A multi-stream comparison. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarstedt, Marko, Joseph F. Hair Jr, Jun-Hwa Cheah, Jan-Michael Becker, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal 27: 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundo-Marcos, Rafael, Ana Merchán Carrillo, Verónica López Fernández, and María Teresa Daza González. 2023. Age-related changes in creative thinking during late childhood: The contribution of Cooperative Learning. Thinking Skills and Creativity 49: 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmer, Norbert K., Achim Elfering, Nicola Jacobshagen, Tanja Perrot, Terry A. Beehr, and Norbert Boos. 2008. The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. International Journal of Stress Management 15: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Huiyoung, and Yujin Chang. 2022. Relational support from teachers and peers matters: Links with different profiles of relational support and academic engagement. Journal of School Psychology 92: 209–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, Kin Wai Michael, and Yi Lin Wong. 2016. Fostering creativity from an emotional perspective: Do teachers recognise and handle students’ emotions? International Journal of Technology and Design Education 26: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Phyllis. 2004. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27: 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Lynda Jiwen, Guo-hua Huang, Kelly Z. Peng, Kenneth S. Law, Chi-Sum Wong, and Zhijun Chen. 2010. The differential effects of general mental ability and emotional intelligence on academic performance and social interactions. Intelligence 38: 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Yu, Jessica I. Jordan, Kelsey A. Shaffer, Erik K. Wing, Kateri McRae, and Christian E. Waugh. 2019. Effects of incidental positive emotion and cognitive reappraisal on affective responses to negative stimuli. Cognition and Emotion 33: 1155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soydan Oktay, Özlem, and T. Volkan Yüzer. 2023. The analysis of interactive scenario design principles supporting critical and creative thinking in asynchronous learning environments. Interactive Learning Environments 32: 4183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Yang, Yu Meng, Zhenya Gao, and Xiangdong Yang. 2022. Perceived teacher support, student engagement, and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology 42: 401–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Ross A. 1994. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 59: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E. Paul. 1972. Predictive validity of the torrance tests of creative thinking. Journal of Creative Behavior 6: 236–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsheim, Torbjoen, Bente Wold, and Oddrun Samdal. 2000. The teacher and classmate support scale: Factor structure, test-retest reliability and validity in samples of 13-and 15-year-old adolescents. School Psychology International 21: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Kathryn, Gwen Sharp, Shi Qingmin, Tony Scinta, and Sandip Thanki. 2020. Fostering historically underserved Students’ success: An embedded peer support model that merges non-cognitive principles with proven academic support practices. The Review of Higher Education 43: 861–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, Sabina, Augusta Veiga-Branco, Hugo Rebelo, Abílio Afonso Lourenço, and Ana Maria Cristóvão. 2020. The relationship between emotional intelligence ability and teacher efficacy. Universal Journal of Educational Research 8: 916–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lei, and Na Jiang. 2022. Managing students’ creativity in music education–the mediating role of frustration tolerance and moderating role of emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 843531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Yan, Keke Zhang, Fangfang Xu, Yayi Zong, Lujia Chen, and Wenfu Li. 2024. The effect of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity: The mediating role of anger and the moderating role of emotion regulation strategies. BMC Psychology 12: 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winks, Lewis, Nicholas Green, and Sarah Dyer. 2020. Nurturing innovation and creativity in educational practice: Principles for supporting faculty peer learning through campus design. Higher Education 80: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Chi-Sum, and Kenneth S. Law. 2002. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly 13: 243–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Li, Rong Huang, Zhe Wang, Jonathan Nimal Selvaraj, Liuqing Wei, Weiping Yang, and Jianxin Chen. 2020. Embodied emotion regulation: The influence of implicit emotional compatibility on creative thinking. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Zhiyong, Qi Liu, and Xinqi Huang. 2022. The influence of digital educational games on preschool Children’s creative thinking. Computers & Education 189: 104578. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Zi, Hongling Lao, Ernesto Panadero, Belén Fernández-Castilla, Lan Yang, and Min Yang. 2022. Effects of self-assessment and peer-assessment interventions on academic performance: A pairwise and network meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 37: 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Yu-Chu, and Me-Lin Li. 2008. Age, emotion regulation strategies, temperament, creative drama, and preschoolers’ creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior 42: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, Cansu, and Tulin Guler Yildiz. 2021. Exploring the relationship between creative thinking and scientific process skills of preschool children. Thinking Skills and Creativity 39: 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Omar, and Jasmin Taylor. 2022. Dispositional mindfulness mediates the relationship between emotion regulation and creativity. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 18: 511–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Yu-Hsi, Ming-Hsiung Wu, Meng-Lei Hu, and I-Chien Lin. 2019. Teacher’s encouragement on creativity, intrinsic motivation, and creativity: The mediating role of creative process engagement. Journal of Creative Behavior 53: 312–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Ying, Zi Yan, Zhi Hong Wan, Xiang Wang, Ye Zeng, Min Yang, and Lan Yang. 2023. Effects of online peer assessment on higher-order thinking: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology 54: 817–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongpo, Cuicui Sun, Xiaoxian Liu, Shaoying Gong, Quanlei Yu, and Zhijin Zhou. 2020. Boys benefit more from teacher support: Effects of perceived teacher support on primary students’ creative thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity 37: 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ruofei, and Di Zou. 2024. Self-regulated second language learning: A review of types and benefits of strategies, modes of teacher support, and pedagogical implications. Computer Assisted Language Learning 37: 720–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Bu, Yakun Huang, and Qian Liu. 2021. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: Social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Computers in Human Behavior 114: 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, Marziyeh, and Vahid Rouhollahi. 2020. Relationship between creativity and emotional intelligence in sport organizations: A gender comparison. Journal of New Studies in Sport Management 1: 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zirak, Mehdi, and Elahe Ahmadian. 2015a. The relationship between emotional intelligence and creative thinking with academic achievement of primary school students of fifth grade. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6: 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zirak, Mehdi, and Elaheh Ahmadian. 2015b. Relationship between emotional intelligence & academic achievement emphasizing on creative thinking. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6: 561–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Di, Haoran Xie, and Fu Lee Wang. 2023. Effects of technology enhanced peer, teacher and self-feedback on students’ collaborative writing, critical thinking tendency and engagement in learning. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 35: 166–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyberaj, Jetmir. 2022. Investigating the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and self-efficacy beliefs among adolescents: Implications for academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools 59: 1556–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Significance Test of Parameters | Composite Reliability | Convergence Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | STDEV | t | p | CR | AVE | ||

| COE | COE1 | 0.885 | 0.012 | 75.466 | *** | 0.904 | 0.704 |

| COE2 | 0.898 | 0.012 | 74.076 | *** | |||

| COE3 | 0.885 | 0.014 | 65.439 | *** | |||

| COE4 | 0.666 | 0.043 | 15.415 | *** | |||

| INE | INE1 | 0.846 | 0.022 | 39.194 | *** | 0.885 | 0.720 |

| INE2 | 0.881 | 0.014 | 64.801 | *** | |||

| INE3 | 0.817 | 0.031 | 26.545 | *** | |||

| DOT | DOT1 | 0.891 | 0.017 | 53.850 | *** | 0.892 | 0.805 |

| DOT2 | 0.903 | 0.012 | 76.005 | *** | |||

| FLY | FLY1 | 0.868 | 0.018 | 48.512 | *** | 0.872 | 0.696 |

| FLY2 | 0.750 | 0.038 | 19.754 | *** | |||

| FLY3 | 0.878 | 0.016 | 55.837 | *** | |||

| INS | INS1 | 0.865 | 0.018 | 48.768 | *** | 0.954 | 0.725 |

| INS2 | 0.832 | 0.024 | 34.756 | *** | |||

| INS3 | 0.894 | 0.014 | 63.083 | *** | |||

| INS4 | 0.676 | 0.041 | 16.372 | *** | |||

| INS5 | 0.872 | 0.018 | 48.493 | *** | |||

| INS6 | 0.868 | 0.016 | 53.322 | *** | |||

| INS7 | 0.913 | 0.012 | 77.109 | *** | |||

| INS8 | 0.868 | 0.018 | 47.371 | *** | |||

| SED | SED1 | 0.829 | 0.024 | 33.870 | *** | 0.937 | 0.750 |

| SED2 | 0.842 | 0.024 | 35.715 | *** | |||

| SED3 | 0.894 | 0.016 | 56.923 | *** | |||

| SED4 | 0.885 | 0.016 | 55.015 | *** | |||

| SED5 | 0.877 | 0.017 | 52.163 | *** | |||

| Constructs | Correlations of the Latent Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COE | INE | DOT | FLY | INS | SED | |

| COE | 0.839 | |||||

| INE | 0.725 | 0.848 | ||||

| DOT | 0.668 | 0.748 | 0.897 | |||

| FLY | 0.651 | 0.648 | 0.720 | 0.834 | ||

| INS | 0.757 | 0.783 | 0.725 | 0.741 | 0.851 | |

| SED | 0.700 | 0.726 | 0.679 | 0.742 | 0.869 | 0.866 |

| Constructs | Significance Test of Parameters | Composite Reliability | Convergence Validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | STDEV | t | p | CR | AVE | ||

| CRT | COE | 0.850 | 0.018 | 48.239 | *** | 0.953 | 0.772 |

| INE | 0.874 | 0.023 | 38.347 | *** | |||

| DOT | 0.852 | 0.018 | 48.370 | *** | |||

| FLY | 0.855 | 0.018 | 47.026 | *** | |||

| INS | 0.932 | 0.008 | 119.040 | *** | |||

| SED | 0.904 | 0.010 | 93.257 | *** | |||

| OEA | OEA1 | 0.824 | 0.022 | 37.499 | *** | 0.911 | 0.719 |

| OEA2 | 0.882 | 0.014 | 64.887 | *** | |||

| OEA3 | 0.827 | 0.027 | 30.749 | *** | |||

| OEA4 | 0.856 | 0.018 | 46.542 | *** | |||

| PES | PES1 | 0.895 | 0.016 | 55.413 | *** | 0.932 | 0.821 |

| PES2 | 0.931 | 0.011 | 87.942 | *** | |||

| PES3 | 0.893 | 0.016 | 56.469 | *** | |||

| ROE | ROE1 | 0.921 | 0.013 | 69.927 | *** | 0.956 | 0.878 |

| ROE2 | 0.930 | 0.011 | 85.939 | *** | |||

| ROE3 | 0.959 | 0.005 | 187.878 | *** | |||

| SEA | SEA1 | 0.866 | 0.023 | 38.410 | *** | 0.933 | 0.822 |

| SEA2 | 0.935 | 0.010 | 94.840 | *** | |||

| SEA3 | 0.918 | 0.012 | 74.491 | *** | |||

| TES | TES1 | 0.812 | 0.027 | 30.467 | *** | 0.910 | 0.716 |

| TES2 | 0.881 | 0.015 | 58.464 | *** | |||

| TES3 | 0.802 | 0.024 | 33.206 | *** | |||

| TES4 | 0.886 | 0.015 | 58.351 | *** | |||

| UOE | UOE1 | 0.920 | 0.011 | 82.070 | *** | 0.949 | 0.861 |

| UOE2 | 0.948 | 0.007 | 130.130 | *** | |||

| UOE3 | 0.916 | 0.015 | 61.159 | *** | |||

| Constructs | Correlations of the Latent Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRT | OEA | PES | ROE | SEA | TES | UOE | |

| CRT | 0.878 | ||||||

| OEA | 0.691 | 0.848 | |||||

| PES | 0.59 | 0.574 | 0.906 | ||||

| ROE | 0.755 | 0.637 | 0.578 | 0.937 | |||

| SEA | 0.635 | 0.641 | 0.632 | 0.594 | 0.907 | ||

| TES | 0.488 | 0.513 | 0.678 | 0.51 | 0.616 | 0.846 | |

| UOE | 0.712 | 0.566 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.566 | 0.469 | 0.928 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Significance Test of Hypothesis | 95% CI | Conclusion | Model Fit Index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std Beta | STDEV | t | p | 2.50% | 97.50% | R2 | f2 | Q2 | |||

| H1e | PES -> SEA | 0.396 | 0.070 | 5.675 | *** | 0.259 | 0.533 | Supported | 0.464 | 0.158 | 0.376 |

| H3b | TES -> SEA | 0.347 | 0.065 | 5.316 | *** | 0.219 | 0.475 | Supported | 0.121 | ||

| H2a | PES -> UOE | 0.411 | 0.066 | 6.183 | *** | 0.281 | 0.541 | Supported | 0.311 | 0.132 | 0.264 |

| H3c | TES -> UOE | 0.190 | 0.066 | 2.860 | ** | 0.060 | 0.320 | Supported | 0.028 | ||

| H1d | PES -> ROE | 0.430 | 0.066 | 6.523 | *** | 0.301 | 0.559 | Supported | 0.359 | 0.156 | 0.312 |

| H3a | TES -> ROE | 0.218 | 0.069 | 3.156 | ** | 0.083 | 0.353 | Supported | 0.040 | ||

| H1c | PES -> OEA | 0.418 | 0.067 | 6.230 | *** | 0.286 | 0.549 | Supported | 0.357 | 0.147 | 0.248 |

| H2e | TES -> OEA | 0.230 | 0.068 | 3.385 | ** | 0.097 | 0.363 | Supported | 0.044 | ||

| H1b | PES -> CRT | 0.084 | 0.048 | 1.759 | 0.079 | −0.010 | 0.177 | Not | 0.699 | 0.010 | 0.529 |

| H2d | TES -> CRT | −0.057 | 0.041 | 1.377 | 0.168 | −0.138 | 0.024 | Not | 0.005 | ||

| H2c | SEA -> CRT | 0.121 | 0.047 | 2.573 | * | 0.029 | 0.213 | Supported | 0.021 | ||

| H1a | OEA -> CRT | 0.233 | 0.045 | 5.160 | *** | 0.145 | 0.322 | Supported | 0.084 | ||

| H3d | UOE -> CRT | 0.262 | 0.056 | 4.716 | *** | 0.153 | 0.371 | Supported | 0.108 | ||

| H2b | ROE -> CRT | 0.335 | 0.053 | 6.334 | *** | 0.231 | 0.438 | Supported | 0.152 | ||

| Paths | Significance Test of Hypothesis | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std Beta | STDEV | t | p | 2.50% | 97.50% | |

| Total Effect | ||||||

| PES -> CRT | 0.481 | 0.052 | 9.284 | 0.000 | 0.379 | 0.582 |

| TES -> CRT | 0.162 | 0.056 | 2.872 | 0.004 | 0.051 | 0.272 |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||

| TES -> ROE -> CRT | 0.073 | 0.026 | 2.817 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.124 |

| PES -> OEA -> CRT | 0.097 | 0.026 | 3.727 | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.149 |

| PES -> SEA -> CRT | 0.048 | 0.021 | 2.317 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.088 |

| TES -> UOE -> CRT | 0.050 | 0.021 | 2.351 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.091 |

| PES -> ROE -> CRT | 0.144 | 0.033 | 4.320 | 0.000 | 0.079 | 0.209 |

| PES -> UOE -> CRT | 0.108 | 0.028 | 3.885 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.162 |

| TES -> OEA -> CRT | 0.054 | 0.018 | 2.973 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.089 |

| TES -> SEA -> CRT | 0.042 | 0.019 | 2.235 | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.079 |

| Direct Effect | ||||||

| PES -> CRT | 0.084 | 0.048 | 1.734 | 0.083 | −0.011 | 0.178 |

| TES -> CRT | −0.057 | 0.041 | 1.385 | 0.166 | −0.137 | 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wei, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, K. Effects of Peer and Teacher Support on Students’ Creative Thinking: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Emotion Regulation Strategy as a Moderator. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050053

Shi Y, Cheng Q, Wei Y, Liang Y, Zhu K. Effects of Peer and Teacher Support on Students’ Creative Thinking: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Emotion Regulation Strategy as a Moderator. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(5):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050053

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yafei, Qi Cheng, Yantao Wei, Yunzhen Liang, and Ke Zhu. 2025. "Effects of Peer and Teacher Support on Students’ Creative Thinking: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Emotion Regulation Strategy as a Moderator" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 5: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050053

APA StyleShi, Y., Cheng, Q., Wei, Y., Liang, Y., & Zhu, K. (2025). Effects of Peer and Teacher Support on Students’ Creative Thinking: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Emotion Regulation Strategy as a Moderator. Journal of Intelligence, 13(5), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13050053