The Impact of Critical, Creative, Metacognitive, and Empathic Thinking Skills on High and Low Academic Achievements of Pre-Service Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Unquestioning acceptance of data input;

- Non-questioning;

- Inability to determine the common denominator across current and prior knowledge;

- Acceptance of previous methods instead of trying novel solutions.

- Query, analysis, evaluation, and discussion of assumptions during investigation.

- Investigation of the causality of decisions during comprehensive thinking.

- Independence during free thinking.

- Confirming, correcting, or replacing the existing value system with a new belief during reconstruction.

- A response similar to the emotional and cognitive state of another individual (Rasoal et al. 2011).

- An individual’s efforts to accurately understand the emotions and thoughts of another individual (Dökmen 2002).

- Recognition of the emotions of others and the factors that led to these emotions (Keen 2007).

- Recognition and management of one’s own emotions, as well as sensitivity to the emotions, desires, and needs of others (Goleman 2005).

- The ability to put oneself in someone else’s shoes regarding emotions and thoughts (TDK 2011).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Model

2.2. The Study Groups

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

- Demographic data form: The form was developed by the authors and included demographic questions (gender and department of the pre-service teachers).

- Academic achievement: In this study, academic achievement, which serves as the dependent variable, is defined as the overall academic grade point average (GPA) of pre-service teachers. Data on this variable were collected through a short-response question in the “Demographic data form”. Academic GPA was self-reported by students.

- Creative thinking aptitude scale: Marmara’s creative thinking attributes scale, developed by Özgenel and Çetin (2017), includes 25 items and six factors. Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient is 0.93 for the entire scale.

- Critical thinking aptitude scale: The scale was adapted to the Turkish language by Kılıç and Şen (2014) and includes 25 items. The Cronbach alpha internal consistency coefficient was calculated as 0.92 with the data collected in the present study for the entire scale, 0.87 for the participation dimension, 0.79 for the cognitive maturity dimension, and 0.78 for the innovation dimension.

- Metacognitive thinking scale: The scale was adapted to the Turkish language by Büyüköztürk et al. (2004). In the present study, 12 items in the metacognitive thinking subscale of the main scale were employed. The scale is a seven-point Likert-type scale. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.84.

- Basic empathy scale: The Likert-type scale was adapted to the Turkish language by Topçu et al. (2010). In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of the scale was calculated as 0.81 for the emotion dimension and 0.78 for the cognitive dimension.

- Creative thinking scale: χ2/df = (350.87/275) = 1.27, RMSEA = 0.08.

- Critical thinking scale: χ2/df = (322.42/275) = 1.17; RMSEA = 0.07.

- Metacognitive thinking scale: χ2/df = (60.03/54) = 1.11; RMSEA = 0.06.

- Basic empathy scale: χ2/df = (190.67/169) = 1.12; RMSEA = 0.05.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

- The academic achievement of pre-service teachers increased by 1.109 with the increase in their creative thinking score (p < 0.05).

- The academic achievement of pre-service teachers increased by 1.106 with the increase in their critical thinking score (p < 0.05).

- The academic achievement of pre-service teachers increased by 1.041 with the increase in their metacognitive thinking score (p < 0.05).

- The increase in empathy skills positively affected academic achievement; however, the effect was not significant (p > 0.05).

- The above-mentioned findings demonstrated that the impact of creative thinking skills was the most significant on academic achievement, while empathy skills had the least effect.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agresti, Alan. 1996. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Xiaoxia. 1999. Creativity and academic achievement: An investigation of gender differences. Creativity Research Journal 12: 329–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Kenichi. 2006. Relations among self-efficacy, goal setting, and metacognitive experiences in problemsolving. Psychological Reports 98: 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonietti, Alessandro, Sabrına Ignazi, and Patrizio Perego. 2000. Metacognitive knowledge about problem solving methods. The British Journal of Educational Psychology 70: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Serhat. 2014. An Investigation of the relationships between metacognition and self regulation with structural equation. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences 6: 603–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, Serhat. 2015. Investigating predictive role of critical thinking on metacognition with structural equation modeling. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Esra. 2001. Turkish Version of the Torrance Creative Thinking Test. M.U. Atatürk Faculty of Education Journal of Educational Sciences 14: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, Medine, and A. Kadir Maskan. 2011. A study of relationships between academic self concepts, some selected variables and physics course achievement. International Journal of Education 3: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başbay, Makbule. 2013. Analysing the relationship of Critical Thinking and Metacognition with epistemological beliefs through structural equation modeling. Education and Science 38: 249–62. [Google Scholar]

- Belet, S. Dilek, and Meral Güven. 2011. Meta-cognitive strategy usage and epistemological beliefs of primary school teacher trainees. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 11: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi-Coletta, Bernadette, Linda S. Buyer, Roger L. Dominowski, and Elizabeth R. Rellinger. 1995. Metacognition and problemsolving: A process-oriented approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 21: 205–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla, María J., Donna Fernández-Nogueira, Manuel Poblete, and Hector Galindo-Domínguez. 2019. Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: The teacher’s view. Thinking Skills and Creativity 33: 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Susan. 2005. Teaching students to think critically. The Education Digest 70: 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Benjamin S. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: McKay. [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart, Susan M. 2010. How to Assess Higher Level Thinking Skills in Your Classroom. Alexandria: ASCD. Available online: http://www.ascd.org (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Brown, Timothy A. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Tanis, and Carol Nelson. 1994. Doing homework: Perspectives of elementary and junior high school students. Journal of Learning Disabilities 7: 488–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Şener, Özcan E. Akgün, Özden Özkahveci, and Funda Demirel. 2004. The Validity and Reliability Study the Turkish Version of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice 4: 207–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cautinho, Savia A. 2007. The relationship between goals, metacognition and academic success. Educate 7: 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Choorapanthiyil, Mathew J. 2007. How İnternational Teaching Assistants Conceptualize Teaching Higher Order Thinking: A Grounded Theory Approach. Ph.D. thesis, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, Chee, and Phaik K. Cheah. 2009. Teacher perceptions of critical thinking among students and its influence on higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 20: 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, Savia, Katja Wiemer-Hastings, Jhon J. Skowronski, and M. Anne Britt. 2005. Metacognition, need for cognition and use of explanations during ongoing learning and problem solving. Learning and Individual Differences 15: 321–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2005. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Çokluk, Ömay, Güçlü Şekercioğlu, and Şener Büyüköztürk. 2016. Multivarite Statistical SPSS and LISREL Applications for Social Sciences. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessioa, Fernando A., Beatrice E. Avolioa, and Vincent Charles. 2019. Studying the impact of critical thinking on the academic performance of executive MBA students. Thinking Skills and Creativity 31: 275–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Mehmet K. 2012. Analyzing empathy skills of primary school teacher candidates. Buca Faculty of Education Journal 33: 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, Necmi. 2010. The Comparison of the Emphatic Skill Levels of Administrators and the Teachers at Primary Schools. Master’s thesis, Council of Higher Education Thesis Center, Yeditepe University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Dökmen, Üstün. 2002. Communication Conflicts and Empathy, 18th ed. Ankara: Sistem Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Elikesik, Meral, and Mete Alım. 2014. The Investigation of Empathic Skills of Social Sciences Teachers in Terms of Some Variables. Journal of Graduate School of Social Sciences 17: 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğdu, Mustafa Y. 2006. Relationships between creativity, teacher behaviours and academic success. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences 5: 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Erfani, Nasrolah, and Zahra S. Azad. 2013. The relationship between state meta-cognition and creativity with academic achievement of students. Technical Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 3: 3231–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, Hülya. 2004. Relationship between student characteristics and academic achievement in distance education and application on students of Anadolu University. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 5: 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Alec. 2001. Critical Thinking: An Introduction. What Is Critical Thinking and How to Improve It? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, John H. 1979. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist 34: 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, Nadia M., and Elena Hurjui. 2015. Critical thinking in elementary school children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 565–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, Marry. 2010. Bloom’s taxonomy. Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology 41: 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, Jack R., and Norman E. Wallen. 2006. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanizadeh, Afsaneh. 2017. The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. High Education 74: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, Daniel. 2005. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Translated by B. Seçkin Yüksel. Turkish Translation. İstanbul: Varlık Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, Firdevs. 2012. Improving the Thinking Skills of Students. Journal of Turkology Research 32: 127–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gürtunca, Aslı. 2013. Empathy Scale for Children and Adolescents: Turkish Validity and Reliability Study. Master’s thesis, Institute of Social Sciences, İstanbul Arel University, İstanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Gürüz, Demet, and Ayşe Temel-Eğinli. 2013. Interpersonal Communication. Ankara: Nobel Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Güven, Meral, and Dilruba Kürüm. 2006. Relationship between learning styles and critical thinking: A general review. Social Sciences Journal 6: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harpster, David L. 1999. A Study of Possible Factors That Influence The Construction of Teacher-Made Problems That Asses Higher-Order Thinking Skills. Ph.D. thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Hope J. 2001. Metacognition in Learning and Instruction: Theory Research and Practice. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitt, William G. 1998. Critical Thinking: An Overview. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta: Valdosta State University. [Google Scholar]

- Javaeed, Arslaan, Asifa Abdul Rasheed, Anum Manzoor, Qurra-Tul Ain, Prince Raphael D Costa, and Sanniya Khan Ghauri. 2022. Empathy scores amongst undergraduate medical students and its correlation to their academic performance. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism 10: 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, Yalçın, Elif I. Demirarslan, Özgür Aslan, Pınar Tektas, and Nurhayat Kiliç. 2017. Critical thinking skill and academic achievement development in nursing students: Four-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Educational Research and Reviews 2: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, Fatma. 2018. The empathetic tendency level of German language teacher candidates. Batman University Journal of Life Sciences 1: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Nilüfer, and Tahsin Fırat. 2011. The comparison of the Attitudes of the English language teaching department students in the Faculty of Education towards English and school and academic self-concepts according to various variables. Celal Bayar University Faculty of Education Journal 1: 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, Suzanne. 2007. Empathy and the Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Kenanlar, Selva. 2014. Examination of the Effect of Revised Direct Reading and Thinking Activity (DR-TA) Strategy on the Development of Higher Order Thinking Skills in Reading. Doctoral thesis, Necmettin Erbakan University, Konya, Turkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kyung H. 2005. Can only intelligent people be creative? A meta-analysis. Prufrock Journal 16: 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, Hülya E., and Ahmet İ. Şen. 2014. UF/EMI Trurkish adaptation study of UF/EMI critical thinking disposition instrument. Education and Science 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıraç, Buket, and Şenel Elaldı. 2023. Evaluation of the effect of Problem-Based Learning on Higher Level thinking Skills: A meta-thematic analysis. Turkish Academic Research Review 8: 1200–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, Leonard. S. 1996. Critical thinking in general chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education 73: 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, Necla, and Suna Çöğmen. 2018. Critical thinking and communication skills of secondary school students. PAU Journal of Education 44: 278–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, Jaco, and Liesl Van der Merwe. 2012. Learning about the world: Developing higher order thinking in music education. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 8: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krznaric, Roman. 2008. You Are Therefore I Am: How Empathy Education Can Create Social Change. Oxford: Oxfam GB Research Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Deanna, and David Dean, Jr. 2004. Metacognition: A bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practise. Theory into Practise 43: 268–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, RuthAnne. 2002. Enhancing metacognition through the reflective use of self-regulated learning strategies. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 33: 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnaz-Adıbatmaz, Fatma B., and Ömer Kutlu. 2020. Measuring Scientific Thinking Skills. Ankara: Pegem Akademy. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzgun, Yıldız. 2000. Guidance in Primary Education. Ankara: Nobel Publishing Distribution. [Google Scholar]

- León, Jenny M. 2015. A baseline study of strategies to promote critical thinking in the preschool classroom (Un Estudio de Base sobre Estrategias para la Promoción de Pensamiento Critico en las Aulas de Preescolar). GIST Education and Learning Research Journal 10: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Arthur, and David Smith. 1993. Defining Higher Order Thinking. Theory into Practice 32: 131–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, Jennifer A. 1997. Metacognition: An Overview. Buffalo: State University of New York at Buffalo. [Google Scholar]

- Magno, Carlo. 2010. The role of metacognitive skills in developing critical thinking. Metacognition Learning 5: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, Bhawani P. 2012. Higher order thinking in education. Academic Voices: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2: 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2014. Designing Qualitative Research. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- MEB [Ministry of Education in Turkey]. 2023. Research Report on 21st Century Skills and Values; Ankara: (MEB) Publications. Available online: https://ttkb.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2023_05/11153521_21.yy_becerileri_ve_degerlere_yonelik_arastirma_raporu.f (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- MEB [Ministry of Education in Turkey]. 2024. Circular Regarding the Education Model. Available online: https://ogm.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2024_08/19112933_genelge20242025egitimveogretimyiliturkiyeyuzyilimaarifmodelineiliskinisveislemler1.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ming-Lee Wen, Sofia. 1999. Critical Thinking and Professionalism at the University Level. Paper presented at British Educational Research Association Conference, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK, September 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Miri, Barak, Ben-Chaim David, and Zoller Uri. 2007. Purposely teaching for the promotion of higher-order thinking skills: A case of critical thinking. Research in Science Education 37: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nditafon, George, and Emmanuel Noumi. 2018. Didactic Transposition for Inferential and Analogical Thinking, Reasoning and Transfer of School Knowledge for Societal Context-of-Use. Open Access Library Journal 5: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwubiko, Emmanuel C. 2020. A survey on the correlation between student librarians’ empathic behaviour and academic achievement. Library Philosophy & Practice, 4652. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4652/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Orion, Nir, and Yael Kali. 2005. The effect of an earth-science learning program on students’ scientific thinking skills. Journal of Geoscience Education 53: 387–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncü, Türkan. 2003. Comparison of creativity levels of children aged 12–14 years old according to age and gender using Torrance creative thinking tests-shape test. Ankara University Faculty of Language, History and Geography Journal 43: 221–37. [Google Scholar]

- Özdamar, Kazım. 1997. Statistical Data Analysis with Package Programs. Eskişehir: Anadolu University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Özerbaş, Mehmet A. 2011. The effect of creative thinking teaching environment on academic achievement and retention of knowledge. GÜ, Gazi Faculty of Education Journal 31: 675–705. [Google Scholar]

- Özgan, Habib. 1999. Examining the Relationship Between High School Students’ Perceived Empathic Classroom Atmosphere Attitudes and Achievement and Self-Esteem. Master’s thesis, Council of Higher Education Thesis Center, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Özgenel, Mustafa, and Münevver Çetin. 2017. Development of the Marmara creative thinking dispositions scale: Validity and reliability analysis. Marmara University Atatürk Education Faculty Journal of Education and Science 46: 113–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pala, Aynur. 2008. A research on the levels of empathy of prospective teachers. Pamukkale University Faculty of Education Journal 23: 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Palavan, Özcan, and Necati Gemalmaz. 2022. An assessment of the communication sills, intra-family communication levels and empathy levels of high school students. Journal of Eurasian Human Science Research 2: 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Q. 2005. Qualitative Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Zhou, Guo Jing, and Wang Yan. 2010. Promoting Pre-service Teachers’ Critical Thinking Skills byInquiry-Based Chemical Experiment. Innovation and Creativity in Education 2: 4597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoal, Chato, Tomas Jungert, Stephan Hau, and Gerhard Andersson. 2011. Development of a Swedish Version of the Scale of Ethnocultural Empathy. Psychology 2: 568–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnawati, Heri, Hasan Djidu, Kartianom, Ezi Apino, and Risqa D. Anazifa. 2018. Teachers’ knowledge about higher-order thinking skills and its learning strategy. Problems of Education in the 21st Century 76: 215–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richland, Lindsey, and Nina Simms. 2015. Analogy, higher order thinking, and education. WIREs Cognitive Science 6: 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieffe, Carolien, Lizet Ketelaar, and Carin H. Wiefferink. 2010. Assessing empathy in young children: Construction and validation of an empathy questionnaire (EmQue). Personality and Individual Differences 49: 362–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, William, and Janet Strayer. 1996. Empathy, Emotional Expressiveness, and Prosocial Behavior. Child Development 67: 449–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romainville, Marc. 1994. Awareness of cognitive strategies: The relationship between university students’ metacognition and their performance. Studies in Higher Education 19: 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Bahador, Mohammad-taghi Hassani, and Masoumeh Rahmatkhah. 2014. The relationship between EFL learners’ metacognitive strategies, and their critical thinking. Journal of Language Teaching & Research 5: 1167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, Muhammad S., M. I. Yousuf, Shafgat Hussain, and Shumaila Noreen. 2009. Relationship between achievement goals, meta-cognition and academic success in Pakistan. Journal of College Teaching& Learning 6: 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Marc N. K., Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill. 2007. Research Methods for Business Students. Edinburgh Gate/Harlow: FT Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Schroyens, Walter. 2005. Knowledge and thought: An introduction to critical thinking. Experimental Psychology 52: 163–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, Niet M., and Nurjanah Ambo. 2020. The scientific creativity of fifth graders in a STEM project-based cooperative learning approach. Problems of Education in the 21st Century 78: 627–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sıburıan, Jodion, Aloysius Duran Corebıma, İbrohim, and Murni Saptasarı. 2019. The Correlation Between Critical and Creative Thinking Skills on Cognitive Learning Results. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 19: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungur, Nuray. 1997. Creative Thought. İstanbul: Evrim Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2001. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed. Boston: Ally and Bacon Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tanujaya, Benidiktus, Jeinne Mumu, and Gaguk Margono. 2017. The relationship between higher order thinking skills and academic performance of student in mathematics instruction. International Education Studies 10: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TDK (Türk Dil Kurumu). 2011. Turkish Dictionary, 11th ed. Ankara: Turkish Language Association Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Temizkan, Mehmet. 2010. Developing Creative writing skills in Turkish Language Education. Turkology Research 27: 621–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen, Lotta, Henrika Anttila, Kirsi Pyhältö, Tiina Soini, and Janne Pietarinen. 2022. The role of empathy between peers in upper secondary students’ study engagement and burnout. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 978546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, Emel, and Müzeyyen Sevinç. 2010. The effects of thinking skills education on The Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills of Preschool Teacher Candidates. Pamukkale University Journal of Education 27: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tok, Hidayet, Habib Özgan, and Bülent Döş. 2010. Assessing metacognitive awareness and learning strategies as positive predictors for success ın a distance learning class. Mustafa Kemal University Social Sciences Institute Journal 7: 123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, Sacip, and Tuncer Akbay. 2022. Comparison of recursive and non-recursive models of attitude towards problem-based learning, disposition to critical thinking, and creative thinking in a computer literacy course for preservice teachers. Education and Information Technologies 27: 6715–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, Çiğdem, Özgür Erdur-Baker, and Yeşim Çapa-Aydın. 2010. Turkish Adaptation of Basic Empathy Scale: Validity and Reliability Study. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal 4: 174–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozduman-Yaralı, Kevser. 2019. The Effect of the Education Program Based on the Storyline Method on Critical Thinking Skills of Preschool Children. Ph.D. thesis, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Uyaroğlu, Bahar. 2011. Analysing The Relation Between The Empathy Skills, Emotional Intelligence Level And Parent Attitude of Gifted And Normally Developed Primary School Students. Master’s thesis, Hacettepe University Institute of Health Sciences, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Ünsal, Serkan, and Selçuk Kaba. 2022. The characteristics of the skill based questions and their reflections on teachers and students. Kastamonu Education Journal 30: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Lancrin, Stéphan, Carlos González-Sancho, Mathias Bouckaert, Federico de Luca, Meritxell Fernández-Barrerra, Gwénaël Jacotin, Joaquin Urgel, and Quentin Vidal. 2019. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What It Means in School. Educational Research and Innovation. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/fostering-assessing-studentscreative-and-critical-thinking-skills-in-higher-education.htm (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Wang, Shouhong, and Hai Wang. 2011. Teaching Higher Order Thinking in the Introductory MIS Course: A Model-Directed Approach. Journal of Education for Business 86: 208–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, Laure E. 1997. The Use of Multiple Representations, Higher Order Thinking Skills, İnteractivity, and Motivation When Designing a Cd-Rom 98 To Teach Self Similarity. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304351657?pqorigsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Yee, Mei Heong, Widad Binti Othman, Jailani Bin Md Yunos, Tee Tze Kiong, Razali Bin Hassan, and Mimi Mohaffyza Binti Mohamad. 2011. The level of Marzano higher order thinking skills among technical education students. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 1: 121–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ramazan. 2014. The Effect of Interaction Environment and Metacognitive Guidance in Online Learning on Academic Success, Metacognitive Awareness and Transactional Distance. Ph.D. thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Veysel, and H. Eray Çelik. 2009. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL-I: Basic Concepts, Applications, Programming. Ankara: Pegem. [Google Scholar]

- Yurdakul, Bünyamin. 2004. The Effects of Constructivist Learning Approach on Learners’ Problem Solving Skills, Metacognitive Awareness, and Attitudes Towards the Course, and Contributions to Learning Process. Ph.D. thesis, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Mathematics Instruction | 30 | 15.3 |

| Preschool Instruction | 29 | 14.8 | |

| Guidance–Psychological Counseling | 15 | 7.7 | |

| Primary School Instruction | 24 | 12.2 | |

| Turkish Language Instruction | 44 | 22.4 | |

| Social Studies Instruction | 54 | 27.6 | |

| Gender | Female | 126 | 64.3 |

| Male | 70 | 35.7 |

| Academic achievement | Kolmogorov–Smirnov Statistic | df | Sig. |

| 0.141 | 196 | 0.000 |

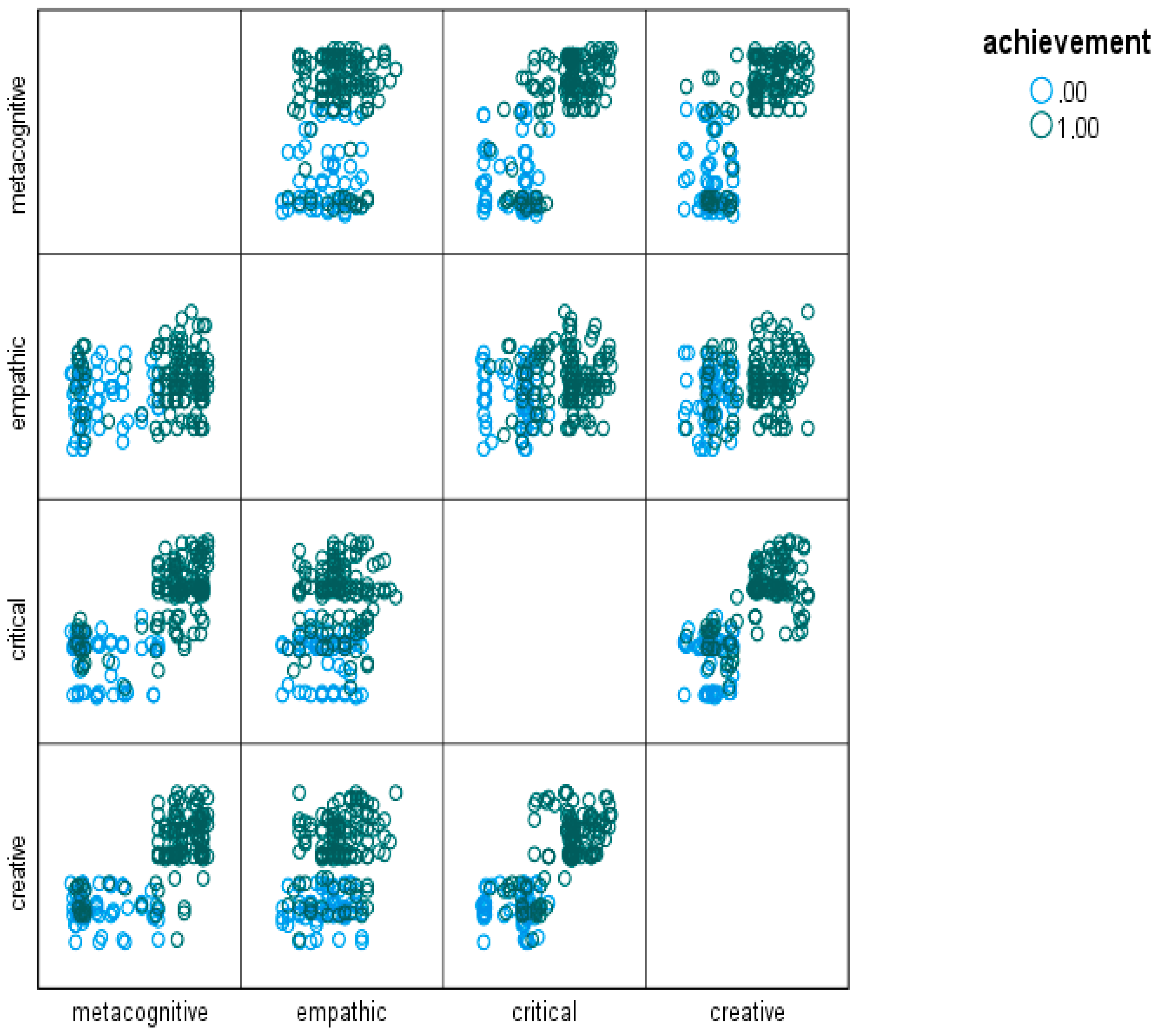

| İndependent Variables | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathic | 196 | 52 | 72 | 61.28 | 4.09 |

| Critical | 196 | 54 | 118 | 88.35 | 16.88 |

| Creative | 196 | 64 | 125 | 95.20 | 16.39 |

| Metacognitive | 196 | 21 | 79 | 54.82 | 20.00 |

| Variable | β | St.Er. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −22.355 | 5.390 | 17.200 | 1.000 | 0.000 * | 0.000 |

| Creative thinking | 0.104 | 0.038 | 7.577 | 1.000 | 0.006 * | 1.109 |

| Critical thinking | 0.100 | 0.033 | 9.359 | 1.000 | 0.002 * | 1.106 |

| Metacognitive thinking | 0.040 | 0.018 | 5.145 | 1.000 | 0.023 * | 1.041 |

| Empathy | 0.076 | 0.068 | 1.247 | 1.000 | 0.264 | 1.079 |

| Observed Achievement | Predicted Achievement | Accuracy Percentage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Achievement | 0.00 | 49 | 10 | 83.1 |

| 1.00 | 17 | 129 | 87.6 | ||

| Overall Percentage | 0 | 86.2 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumandaş-Öztürk, H.; Ulu-Kalın, Ö. The Impact of Critical, Creative, Metacognitive, and Empathic Thinking Skills on High and Low Academic Achievements of Pre-Service Teachers. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13040050

Kumandaş-Öztürk H, Ulu-Kalın Ö. The Impact of Critical, Creative, Metacognitive, and Empathic Thinking Skills on High and Low Academic Achievements of Pre-Service Teachers. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumandaş-Öztürk, Hatice, and Özlem Ulu-Kalın. 2025. "The Impact of Critical, Creative, Metacognitive, and Empathic Thinking Skills on High and Low Academic Achievements of Pre-Service Teachers" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13040050

APA StyleKumandaş-Öztürk, H., & Ulu-Kalın, Ö. (2025). The Impact of Critical, Creative, Metacognitive, and Empathic Thinking Skills on High and Low Academic Achievements of Pre-Service Teachers. Journal of Intelligence, 13(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13040050