Expectations of Personal Life Development and Decision-Making in People with Moderate Intellectual Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Training Program We Are All Campus

1.2. Objectives

- Fathom the main themes around which the expectations and decision-making of students with ID are circumscribed.

- Point out possible differences between students in the initial and advanced courses and between different genders.

- Characterize the type of sentiment produced by each of the emerging themes.

- Establish possible relationships between each of the categories that emerged in the expectations and decision-making of students with ID.

2. Materials and Methods

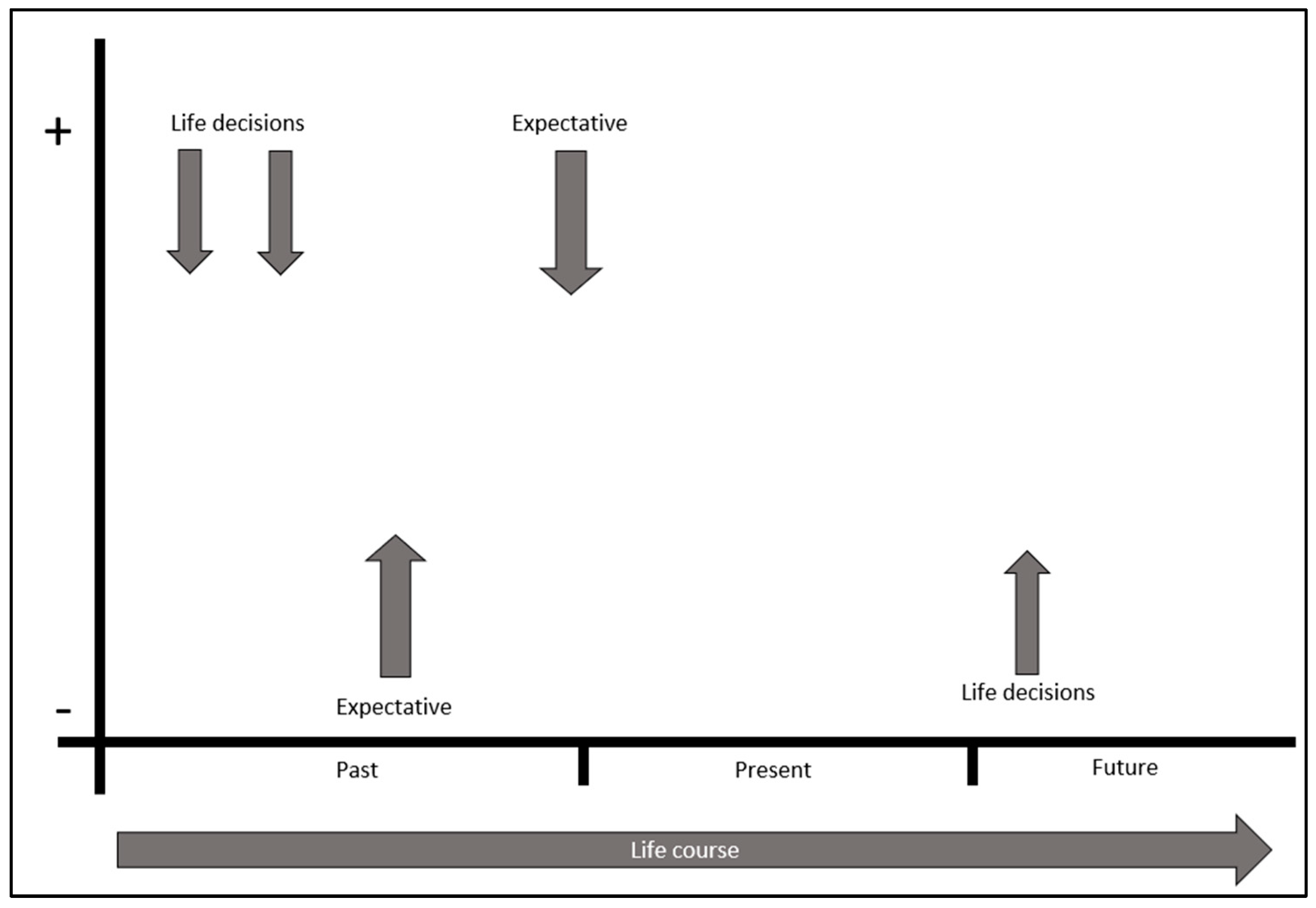

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

- Open coding, at the initial moment of the analysis, identifies different superficial concepts, categorizing data into manageable units that help in the generation of categories.

- Axial coding, at the first moment of theoretical construction. The central categories by which we will structure our discourse emerge. The core categories arise from the most relevant codes. In this phase, we work with the citations linked to the codes to begin to generate content and the different relationships that may arise between them. Here, the ATLAS.ti V22 Analysis tool of co-occurrence was especially relevant.

- Selective coding, last proposal by Strauss and Corbin (2002). The purpose of this is to establish relationships through which the knowledge of the studied phenomenon can be deepened.

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

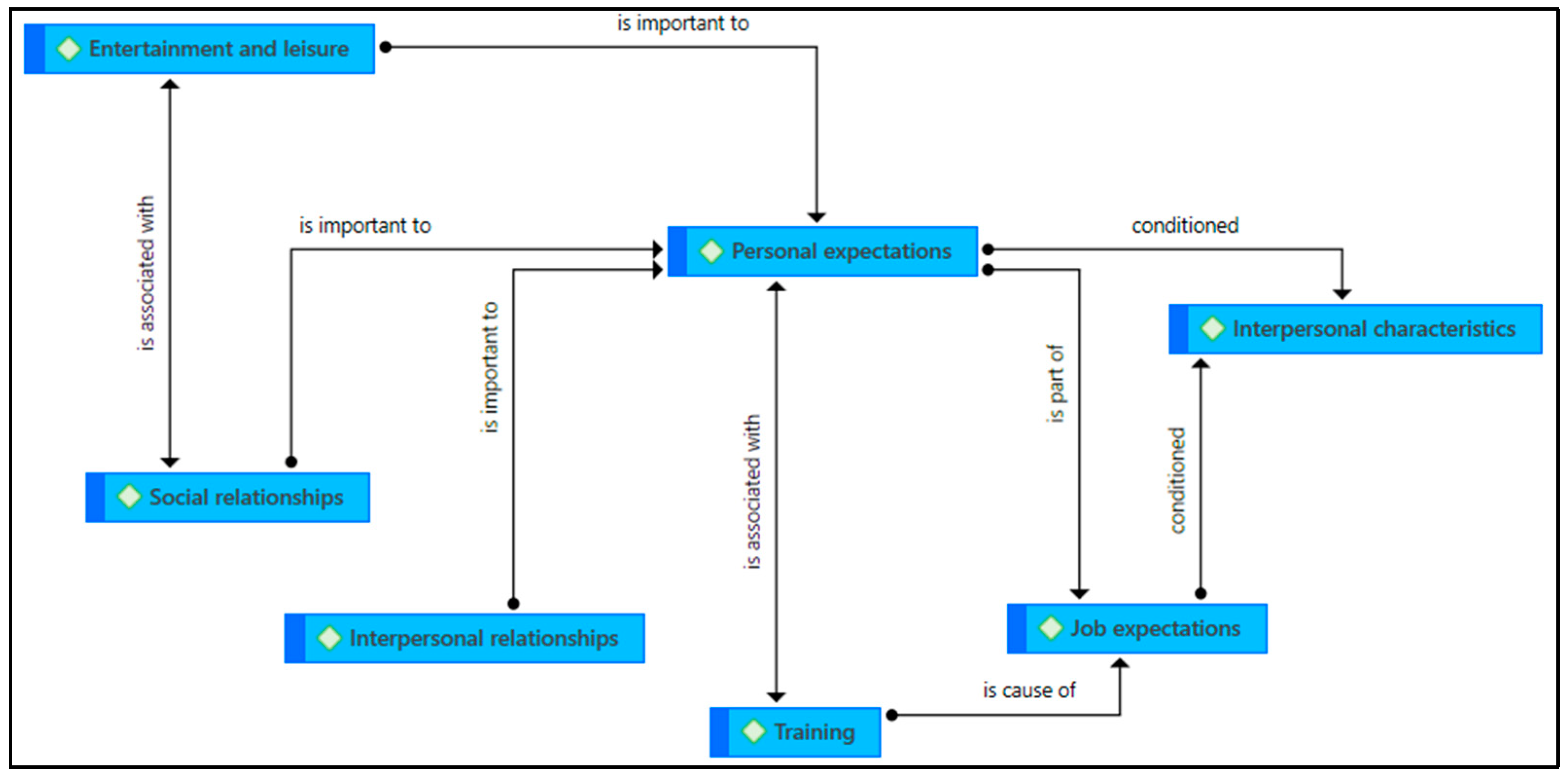

3.1. What Are the Main Issues You Are Discussing?

- Personal expectations: expectations of a personal nature through which they seek their own development, autonomy or ability to choose. “May all my dreams come true”. (D1:60)3. This category was used when participants talked about something specific they wanted to happen. Many of the items refer to goals that the respondents intend to achieve. These expectations are tangible and real for them, although they do not have a very clear path towards achieving them.

- Social relationships: mentions of the different social relationships they can establish and the forms they take. “I am proud to have these colleagues because they are very good people and also to have scored well in the exams”. (D1:67). These types of relationships are not as close as personal ones can be. However, they have a strong effect on these people because, in many cases, this is their first contact with society and their first stage of social development. In addition to classmates, they also manifest relationships of this type with co-workers or other people they meet in their day-to-day lives.

- Interpersonal characteristics: each respondent’s intrinsic characteristics and how these affect their development or occur in the different facets of their lives. “To have learned with my failures and to mature as a person”. (D1:99). Interpersonal characteristics may refer to two specific issues: specific abilities that are, or are not, in them, and over which they may assume to have a certain control, such as their ability in mathematics; and characteristics derived from aspects that they do not believe they can control or that are difficult to modify or improve, such as those related to their disability.

- Training: references to training they have acquired or training they want to undertake. “I choose to learn new things like cooking recipes, sports, languages”. (D1:79). The participants understand that there is a need to train constantly, and they express it this way. Training is the means by which they can improve and acquire the skills or abilities that are necessary for their development or to develop leisure activities.

- Entertainment and leisure: category used when mentioning leisure activities. “Going for a walk with my friends and monitors”. (D1:113). Closely linked to the other categories, the participants constantly mention the leisure activities that they carry out or those that they perceive as a need. These are the main activities in their daily lives that give them satisfaction.

- Interpersonal relationships: comments concerning the closest relationships, those of family or intimate relatives. “I am proud to have had a family that loves me”. (D1:157). The respondents refer to these when they talk about their closest relationships. Such relationships are especially relevant because they strongly influence daily life and pertain to one’s immediate environment.

- Job expectations: related to the interviewees’ job expectations. “To be able to be autonomous and be able to work tomorrow”. (D1:224). One of the main aspirations presented by students is the desire to get a job which will give them autonomy. This is accompanied by a need to feel useful and valued by society and by the people closest to them. For these reasons, the respondents frequently expressed their expectations of having a job.

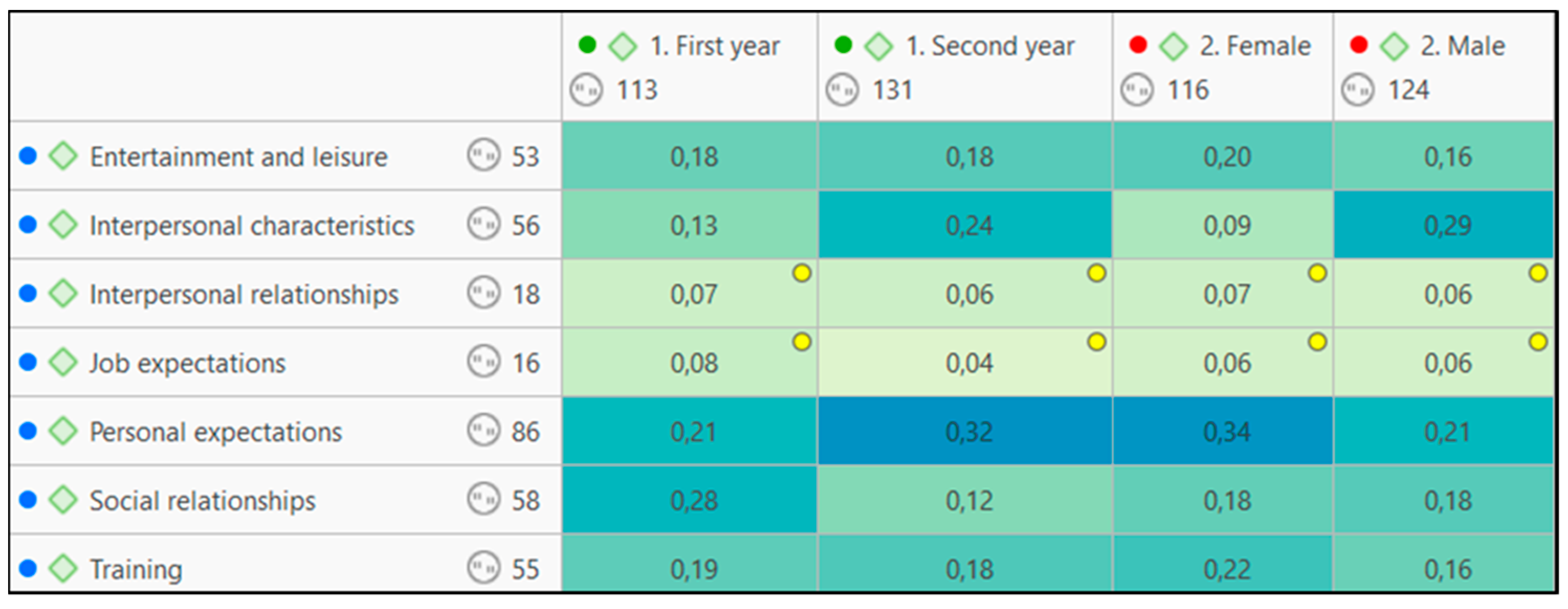

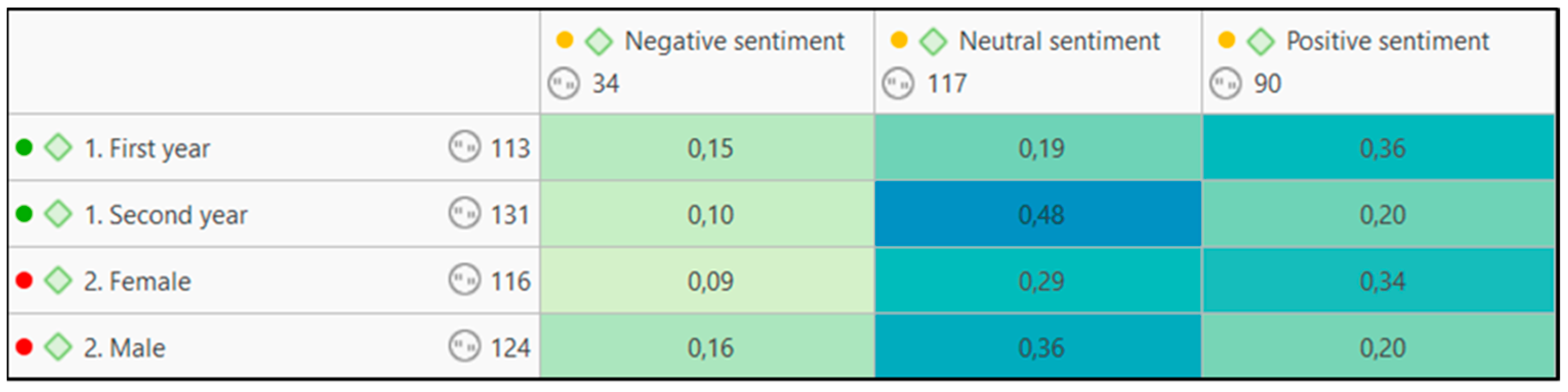

3.2. Main Differences between Gender and Course

4. Discussion

4.1. The Hope Placed in Your Future, on Personal Development

4.2. The Importance of Personal Relationships

4.3. Training and Work as a Way Forward

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The percentage of disability is officially determined by a National Health Service evaluation and is officially recognized throughout the state. This means that the National Health Service Assessment and Guidance Teams apply a nationally established scale to identify the degree of disability a person may have. |

| 2 | Own studies in Spanish universities refer to the set of degrees recognized by the university itself. They are not approved or regulated at the state level. More information at: https://www.um.es/web/estudios-propios/. |

| 3 | To reference the citations extracted from the data, the coding offered by the ATLAS.ti 22 program has been used. The first number indicates the document where the appointment is located and the second is the appointment within said document. |

| 4 | Different coefficients of co-occurrence offered by the software will be shown, indicating the intensity or strength of relationship between two codes based on the number of times they appear simultaneously in a quotation. With respect to the strength of the relationship between two codes, it is not necessary to arrive at a minimum coefficient for consideration. It is necessary to analyze them individually. |

| 5 | In the different figures facilitated by the ATLAS.ti software, a greater intensity of relationship is reflected in proportionally darker colours, in addition to presenting a higher coefficient of co-occurrence, as indicated above. Yellow circles indicate that the coefficient is out of range, so it is not considered for use in the results. |

References

- Alarcón, Andrés, Liris Munera, and Alexander Montes. 2017. La teoría fundamentada en el marco de la investigación educativa. Saber Ciencia y Libertad 12: 236–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, Salvador, and Pilar Arnáiz. 2020. La escolarización del alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales en España: Un estudio longitudinal. Revista Colombiana de Educación 78: 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, María Luisa, and Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez. 2021. Evaluation of Self-Concept in the Project for People with Intellectual Disabilities: “We Are All Campus”. Journal of Intelligence 9: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmonte, María Luisa, Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez, and Ana B. Mirete. 2021. La voz del silencio: Evaluación cualitativa de prácticas de bullying en personas con discapacidad intelectual. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial 27: 215–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, María Luisa, Ana Belen Mirete, and Lucía Mirete. 2022. Experiencias de vida para fomentar el cambio actitudinal hacia la discapacidad intelectual en el aula. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 25: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernárdez-Gómez, Abraham. 2022. Vulnerabilidad, Exclusión y Trayectorias Educativas de Jóvenes en Riesgo. Madrid: Dykinson. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazalla, Nerea, and David Molero. 2018. Emociones, afectos, optimismo y satisfacción vital en la formación inicial del profesorado. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 22: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, Javier, María Luz López, and María Jesús Rubio. 2016. Inteligencia emocional y resiliencia: Su influencia en la satisfacción con la vida de estudiantes universitarios. Anuario de Psicología 46: 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneally, Sean, Grainne Boyle, and Frances Smyth. 1992. An evaluation of the use of small group homes for adults with a severe and profound mental handicap. Mental Handicap Research 5: 146–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Eric, Janet Robertson, Nicky Gregory, Sophia Kessissoglou, Chris Hatton, Angela Hallam, Martin Knapp, Järbrink Krister, Ann Netter, and Christine Linehan. 2000. The quality and costs of community-based residential supports and residential campuses for people with severe and complex disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 25: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, Louse F., and Nancy E. Betz. 1994. Career development in cultural context: The role of gender, race, class and sexual orientation. In Convergence in Career Development: Implications for Science and Practice. Edited by Mark L. Savickas and Robert W. Lent. Palo Alto: CPP, pp. 103–17. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, Susan, and Judith T. Moskovitz. 2000. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist 55: 647–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Yamely A., and Johann P. Morillo. 2016. Glasser y Strauss: Construyendo una teoría sobre apropiación de la gaita zuliana. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 22: 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavín, Óscar, and David Molero. 2020. Valor predictivo de la Inteligencia Emocional Percibida y Calidad de Vida sobre la Satisfacción Vital en personas con Discapacidad Intelectual. Revista de Investigación Educativa 38: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavín, Óscar, David Molero, and Sonia Rodríguez. 2022. Mediator Effect of Vital Satisfaction between Emotional Intelligence and Optimism in People with Intellectual Disability. Siglo Cero 53: 145–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, María Cristina, Paola Magnano, Ernesto Lodi, Chiara Annovazzi, Elisabetta Camussi, Patrizia Patriz, and Laura Nota. 2018. The role of career adaptability and courage on life satisfaction in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 62: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, Laura E., M. Lucía Morán, Susana Al-Halabí, Chris Swerts, Miguel A. Verdugo, and Robert L. Schalock. 2022. Quality of life and the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Consensus indicators for assessment. Psicothema 34: 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Blas, Moisés Mañas, and Pablo Cortés. 2017. Narrarse-se para transformar-se. Miradas subversivas a la discapacidad. Revista del Instituto de Investigaciones en Educación 10: 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Edward. 2010. Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54: 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, Inés, Antonio Manuel Amor, Miguel A. Verdugo, and María I. Calvo. 2021. Operationalisation of quality of life for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities to improve their inclusion. Research in Developmental Disabilities 119: 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, Roberto, Carlo Fernández, and Pilar Baptista. 2018. Metodología de la Investigación. New York: McGrawHill. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, James, David Reeves, Jessica Roberts, and Oliver C. Mudford. 2001. Consistency, context and confidence in judgements of affective communication in adults with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 45: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostyn, Ine, and Bea Maes. 2009. Interaction between persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities and their partners: A literature review. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 34: 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, Agnes, Jim Mansell, and Julie Beadle-Brown. 2009. Outcomes in different residential settings for people with intellectual disability: A systematic review. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 114: 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtek, Pawel. 2020. Causal attribution and coping with classmates’ isolation and humiliation in young adults with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour 11: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakin, K. Charlie, Sheryl A. Larson, and Shannon Kim. 2011. Behavioral Outcomes of Deinstitutionalization for People with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities: Third Decennial Review of US Studies, 1977–2010. Minneapolis: Minnesota, Research and Training Center on Community Living, Institute on Community Integration. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, Robert W., and Gail Hackett. 1994. Sociocognitive mechanisms of personal agency in career development: Pan theoretical prospects. In Convergence in Career Development: Implications for Science and Practice. Edited by Mark L. Savickas and Robert W. Lent. Palo Alto: CPP, pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas, Moisés, Blas González, and Pablo Cortés. 2020. Historias de vida de personas con discapacidad intelectual: Entre el acoso y exclusión en la escuela como moduladores de la identidad. Revista Educación, Política y Sociedad 5: 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- McConkey, Roy, Fiona Keogh, Brendan Bunting, Edurne Garcia-Iriarte, and Sheela F. Watson. 2016. Relocating people with intellectual disability to new accommodation and support settings: Contrasts between personalized arrangements and group home placements. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 20: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, Begoña, and Roberto Gil-Ibáñez. 2017. Estrés y estrategias de afrontamiento en personas con discapacidad intelectual: Revisión sistemática. Ansiedad y Estrés 23: 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirenda, Pat. 2014. Revisiting the mosaic of supports required for including people with severe intellectual or developmental disabilities in their communities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 30: 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirete, Ana Belén, María Luisa Belmonte, Lucía Mirete, and Mari Paz García-Sanz. 2022. Predictors of attitudes about people with intellectual disabilities: Empathy for a change towards inclusion. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 68: 615–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Irene, and María L. Belmonte. 2022. Orientación laboral para estudiantes con discapacidad intelectual de la Universidad de Murcia. Diálogos Pedagógicos 20: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, Patricia, Miguel A. Verdugo, Sergio Martínez, Fabian Sainz, and Alba Aza. 2017. Derechos y calidad de vida en personas con discapacidad intelectual y mayores necesidades de apoyo. Siglo Cero 48: 7–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Patricia, Avril Thesing, Bryan Tuck, and Angus Capie. 2001. Perceptions of change, advantage and quality of life for people with intellectual disability who left a long stay institution to live in the community. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 26: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onghena, Patrick, Bea Maes, and Mieke Heyvaert. 2019. Mixed methods single case research: State of the art and future directions. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 13: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallisera, María, Judit Fullana, Carol Puyaltó, Montserrat Vilà, María J. Valls, Gemma Díaz, and Montse Castro. 2018. Retos para la vida independiente de las personas con discapacidad intelectual. Un estudio basado en sus opiniones, las de sus familias y las de los profesionales. Revista Española de Discapacidad 6: 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Q. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Patricia, María P. Matud, and Javier Álvarez. 2017. Gender and quality of life in adolescence. Journal of Behavior, Health & Social Issues 9: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, Robert L. 2018. Seis ideas que están cambiando el campo de las discapacidades intelectuales y del desarrollo en todo el mundo. Siglo Cero Revista Española Sobre Discapacidad Intelectual 49: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Haleigh M., and Susan M. Havercamp. 2014. Mental health for people with intellectual disability: The impact of stress and social support. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 119: 552–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare, Tom. 2010. The Social Model of Disability. In The Disability Studies Reader, 3rd ed. Edited by Lennard J. Davis. London: Routledge, pp. 266–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shogren, Karrie A., Judith Gross, Anjali Forber-Pratt, Grace Francis, Allyson Satter, Martha Blue-Banning, and Cokethea Hill. 2015. The perspectives of students with and without disabilities on inclusive schools. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 40: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 2002. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa: Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada. Antoquia: Universidad de Antioquia. [Google Scholar]

- Suriá, Raquel. 2017. Redes virtuales y apoyo social percibido en usuarios con discapacidad: Análisis según la tipología, grado y etapa en la que se adquiere la discapacidad. Escritos de Psicología 10: 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie DeVault. 2015. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, Eva, Cristiana Mumbardó-Adam, Teresa Coma, Miguel A. Verdugo, and Giné Climent. 2018. Autodeterminación en personas con discapacidad intelectual y del desarrollo: Revisión del concepto, su importancia y retos emergentes. Revista Española de Discapacidad 6: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, Jorge. 2013. El modelo social de la discapacidad: Una cuestión de derechos humanos. Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado 138: 1093–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Víquez, Camila, Lizbeth López, Marjorie Cordero, and Pamela Alpízar. 2019. Fortalecimiento de la autonomía de jóvenes con discapacidad intelectual mediante la aplicación de las TIC. Innovaciones Educativas 21: 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entertainment and Leisure | Interpersonal Characteristics | Interpersonal Relationships | Job Expectations | Personal Expectations | Social Relationships | Training | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entertainment and leisure | |||||||

| Interpersonal characteristics | 0.04 | ||||||

| Interpersonal relationships | 0.04 | 0.00 | |||||

| Job expectations | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||||

| Personal expectations | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |||

| Social relationships | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||

| Training | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Candel, J.A.; Belmonte, M.L.; Bernárdez-Gómez, A. Expectations of Personal Life Development and Decision-Making in People with Moderate Intellectual Disabilities. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11020024

García-Candel JA, Belmonte ML, Bernárdez-Gómez A. Expectations of Personal Life Development and Decision-Making in People with Moderate Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intelligence. 2023; 11(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11020024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Candel, José Antonio, María Luisa Belmonte, and Abraham Bernárdez-Gómez. 2023. "Expectations of Personal Life Development and Decision-Making in People with Moderate Intellectual Disabilities" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 2: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11020024

APA StyleGarcía-Candel, J. A., Belmonte, M. L., & Bernárdez-Gómez, A. (2023). Expectations of Personal Life Development and Decision-Making in People with Moderate Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Intelligence, 11(2), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11020024